Rainbow trout

| Rainbow trout | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | O. mykiss

|

| Binomial name | |

| Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum, 1792)

| |

The rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) is a species of salmonid native to cold-water tributaries of the Pacific Ocean in Asia and North America. The steelhead is an anadromous (sea-run) form of the Coastal rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss irideus) or redband trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss gairdneri) that usually returns to freshwater to spawn after living two to three years in the ocean. Freshwater forms that have been introduced into the Great Lakes and migrate into tributaries to spawn are also called steelhead.

Adult freshwater stream rainbow trout average between 1 to 5 pounds (0.45 to 2.27 kg), while lake dwelling and anadromous forms may reach 20 pounds (9.1 kg). Although coloration varies widely based on subspecies, forms and habitat, adult fish are distinguished by broad reddish stripe along the lateral line, from gills to the tail which is most pronounced in breeding males.

Wild caught and hatchery reared forms of this species have been transplanted and introduced for food or sport in at least 45 countries, and every continent except Antarctica. Introductions in some locations outside their native range, such as Southern Europe, Australia and South America, and the United States have negatively impacted native fish species, either by preying on them, out-competing them, transmitting contagious diseases, (such as whirling disease) or hybridizing with closely related species and subspecies that are native to western North America. Other introductions into waters previously devoid of any fish species or with severely depleted stocks of native fish have created world class fisheries such as the Firehole River in Wyoming and in the Great Lakes.

A number of local populations of specific subspecies, or in the case of steelhead, distinct population segments are listed as either threatened or endangered.

The steelhead is the official state fish of Washington.[1]

Taxonomy

The scientific name of the rainbow trout is Oncorhynchus mykiss. The species was originally named by Johann Julius Walbaum in 1792 based on type specimens from Kamchatka. Sir John Richardson, a Scottish naturalist, named a specimen of this species Salmo gairdneri in 1836. In 1855, William P. Gibbons, the curator of Geology and Mineralogy[2] at the California Academy of Sciences found a population and named it Salmo iridia (Latin: rainbow), later corrected to Salmo irideus. These names faded, however, once it was determined that Walbaum's type description was conspecific and therefore had precedence (see e.g. Behnke, 1966).[3] In 1989, morphological and genetic studies by Dr. Gerald R. Smith, Curator of Fishes at the Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan and Ralph F. Stearley, doctoral candidate, Museum of Palentology, University of Michigan indicated that trouts of the Pacific basin were genetically closer to Pacific salmon (Onchorhynchus species) than to the Salmos–brown trout (Salmo trutta) or Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) of the Atlantic basin.[4] Thus, in 1989, taxonomic authorities moved the rainbow, cutthroat and other Pacific basin trouts into the genus Onchorhynchus.[5] Walbaum's original species name mykiss was derived from the local Kamchatkan name 'mykizha'. Walbaum's name had precedence so the species name Onchorhynchus mykiss became the scientific name of the rainbow trout. Previous species names irideus and gairdneri were adopted as subspecies names for the coastal rainbow and Columbia River redband trouts respectively.[5] Anadromous forms of the Coastal rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss irideus) or redband trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss gairdneri) are commonly known as steelhead.[6]

Subspecies

North American subspecies of Oncorhynchus mykiss are listed below as described by Behnke (2002)[6]

- Type species

- Kamchatkan rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss mykiss (Walbaum, 1792)

- Coastal rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss irideus (Gibbons, 1855)

- Anadromous forms known as steelhead, freshwater forms known as rainbow trout

- Beardslee trout, isolated in Lake Crescent (Washington), Oncorhynchus mykiss irideus var. beardsleei (not a true subspecies, but a genetically unique lake-dwelling variety of coastal rainbow trout) (Jordan, 1896)[7]

- Redband forms

- Columbia River redband trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss gairdneri (Richardson, 1836)

- Anadromous forms known as redband steehead

- Athabasca rainbow trout, Oncorhunchus mykiss spp, consider by Behnke as form of Oncorhynchus mykiss gairdneri, but considered a separate subspecies by biologist L. M. Carl of the Ontario Ministry of Resources, Aquatic Ecosystems Research Section and associates from work published in 1994.[8]

- McCloud River redband, Oncorhynchus mykiss stonei

- Sheepheaven Creek redband, Oncorhynchus mykiss spp.

- Great Basin redband trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss newberrii (Girard, 1859)

- Eagle Lake trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss aquilarum (Snyder, 1917)

- Kamloops rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss kamloops strain (Jordan, 1892)

- Columbia River redband trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss gairdneri (Richardson, 1836)

- Kern River golden trouts

- Golden trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss aguabonita (Jordan, 1892)

- Kern River rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss gilberti (Jordan, 1894)

- Little Kern golden trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss whitei (Ever ann, 1906)

- Mexico forms

- Mexico rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss nelsoni, sometimes referred to as Nelson's trout, occur in three distinct groups.

- Rio Yaqui, Rio Mayo and Guzman trouts

- Rio San Lorenzo and Arroyo la Sidra trout

- Rio del Presidio trout

- Mexico rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss nelsoni, sometimes referred to as Nelson's trout, occur in three distinct groups.

- Mutated forms

- So-called golden rainbow trout or palomino trout are bred from a single mutated color variant of Oncorhynchus mykiss which originated in a West Virginia fish hatchery in 1955.[9][10] Golden rainbow trout are predominantly yellowish, lacking the typical green field and black spots, but retaining the diffuse red stripe.[10][11] The palomino trout is a mix of golden and common rainbow trout, resulting in an intermediate color. The golden rainbow trout should not be confused with the naturally occurring Oncorhynchus mykiss aguabonita, the Kern river golden trouts of California.[10]

Description

Resident freshwater rainbow trout adults average between 1 to 5 pounds (0.45 to 2.27 kg), while lake dwelling and anadromous forms may reach 20 pounds (9.1 kg). Coloration varies widely between regions and subspecies. Adult freshwater forms are generally blue-green or olive green with heavy black spotting over the length of the body. Adult fish have a broad reddish stripe along the lateral line, from gills to the tail which is most pronounced in breeding males.[6] The caudal fin is squarish and only mildly forked. Lake dwelling and anadromous forms are usually more silvery in color with the reddish stripe almost completely gone. Juvenile rainbow trout display parr marks typical of most salmonid juveniles. In some redband and golden trout forms, large black bars or parr marks are typically retained in adults.[6] In many jurisdictions, hatchery bred trout can be distinquished from native trout via fin clips, most typically, the adipose fin.[12]

Life cycle

Rainbow trout generally spawn in early to late spring (January to June) in the northern hemisphere and (September to November) in the southern hemisphere when water temperatures reach at least 42 to 44 °F (6 to 7 °C).[6] The maximum recorded life-span for a rainbow trout is 11 years.[13]

Steelhead life cycle

The oceangoing (anadromous) form, including those returning for spawning, are known as steelhead,[14] in Canada and the United States. In Tasmania they are commercially propagated in sea cages and known as ocean trout, although they are the same species.[15]

Like salmon, steelhead return to their original hatching ground to spawn. Similar to Atlantic salmon, but unlike their Pacific Oncorhynchus salmonid kin, steelhead are iteroparous (able to spawn several times, each time separated by months) and make several spawning trips between fresh and salt water, although survival rates for native spawning adults is less than 10 percent.[6] The survival rate for introduced populations in the Great Lakes is as high as 70 percent. The steelhead smolts (immature or young fish) remain in the river for about a year before heading to sea, whereas salmon typically return to the seas as smolts. Different steelhead populations migrate into fresh water rivers at different times of the year. "Summer-run steelhead" migrate between May and October, before their reproductive organs are fully mature. They mature in freshwater before spawning in the spring. Most Columbia River steelhead are "summer-run". "Winter-run steelhead" mature fully in the ocean before migrating, between November and April, and spawn shortly after returning.[6] Once steelhead enter riverine systems and reach suitable spawning grounds, they spawn just like resident freshwater rainbows.[6]

Freshwater life cycle

Freshwater resident rainbow trout usually inhabit and spawn in small to moderately large, well oxygenated, shallow rivers with gravel bottoms. They are native to the aluvial or freestone streams that are typical tributaries of the Pacific basin but introduced rainbows have established wild, self-sustaining populations in other river types such as bedrock (limestone) and spring creeks. Lake resident rainbow trout are usually found in moderately deep, cool lakes with adequate shallows and vegetation for good food production. Lake populations generally require access to gravelly bottomed streams to be self-sustaining.[16]

Spawning sites are usually a bed of fine gravel in a riffle above a pool. Female trout clear a redd in the gravel by turning on their side and beating the tail up and down. During spawning, the eggs fall into spaces between the gravel and immediately the female begins digging at the upstream edge of the nest covering the eggs with the displaced gravel. The eggs usually hatch in approximately 4 – 7 weeks; however, the time of hatching varies greatly with region and habitat. The fry commence feeding about 15 days after hatching and their diet consists mainly of zooplankton. The growth rate of rainbow trout is variable with area, habitat, life history and quality and quantity of food.[17]

In streams where rainbow trout are stocked for sport fishing but no natural reproduction occurs, some of the stocked trout may survive and grow or "carryover" for several seasons before they are caught or perish.[18]

Feeding

Rainbow trout are predators with a varied diet, and will eat nearly anything they can capture. Rainbows are not as piscivorous or aggressive as brown trout or chars. Rainbow trout, including young steelhead smolts in freshwater, routinely feed on larval, pupal and adult forms of aquatic insects (typically caddisflies, stoneflies, mayflies and aquatic diptera) and adult forms of terrestrial insects (typically ants, beetles, grasshoppers and crickets) that fall into the water, fish eggs, and small fish (up to one-third of their length), along with crayfish, shrimp and other crustaceans. As they grow, though, the proportion of fish consumed increases in most populations. Some lake-dwelling lines may become planktonic feeders. In rivers and streams populated with other salmonids species, rainbow trout eat varied fish eggs, including salmon, brown and cutthroat trout and mountain whitefish, as well as the eggs of other rainbow trout. Rainbow trout also consume decomposing flesh from carcasses of other fish. Adult steelhead in the ocean feed primarily on other fish, squid and amphipods.[19]

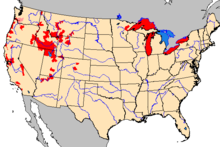

Range

The native range of Oncorhynchus mykiss is in the coastal waters, tributary rivers and streams of the Pacific basin and extends north from the Kamchatka peninsula in Russia, east along the Aleutian Islands, throughout southwest Alaska, the Pacific coast of British Columbia and southeast Alaska, south along the west coast of the United States to northern Mexico. Mexican forms of Oncorhynchus mykiss represent the southernmost native range of any trout or salmon (Salmonidae).[6]

The rainbow trout has been widely introduced into suitable lacustrine and riverine environments inside and outside its native range around the world. A great many of these introductions have established wild, self-sustaining populations.[20]

Artificial propagation

Rainbow trout have been artificially propagated in fish hatcheries to restock streams and for their introduction into non-native waters since 1870. The first rainbow trout hatchery was established on San Leandro Creek, a tributary of San Francisco Bay, in 1870, with trout production beginning in 1871. The hatchery was stocked with the locally native rainbow trout, and likely steelhead of the Coastal rainbow trout subspecies (Oncorhynchus mykiss irideus). The fish raised in this hatchery were shipped to hatcheries out of state for the first time in 1875, to Caledonia, New York and then in 1876 to Northville, Michigan. In 1877, another rainbow trout hatchery, the first federal fish hatchery in the National Fish Hatchery System was established on Campbell Creek, a McCloud River tributary.[21] However, the McCloud River hatchery indiscriminately mixed coastal rainbow trout eggs with local McCloud River Redband trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss stonei) eggs. Eggs from the McCloud hatchery were also provided to the San Leandro hatchery, thus making the origin and genetic history of hatchery bred rainbow trout somewhat diverse and complex.[22]

In the United States, there are 100s of hatcheries operated by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, various state agencies and tribal Indian councils propagating rainbow trout for conservation and recreational sport fishing.[23][24][25][26] Six of ten Canadian provinces have rainbow trout farms, with Ontario leading production.[27]

Introduced rainbow trout in regions outside their native range have established wild, self-sustaining populations where healthy conditions exist for spawning and growth.[28]

Aquaculture

Rainbow trout are farmed in many countries throughout the world. Since the 1950s, commercial production has grown exponentially,[29] particularly in Europe and Chile. Worldwide, in 2007, 604,695 tonnes (595,145 long tons; 666,562 short tons) of farmed salmon trout were harvested with a value of US$ 2.589 billion.[30] The largest producer is Chile. In Chile and Norway, ocean cage production of steelhead has expanded to supply export markets. Inland production of rainbow trout to supply domestic markets has increased in countries such as Italy, France, Germany, Denmark and Spain. Other significant producing countries include the USA, Iran, Germany and the United Kingdom.[30]

Rainbow trout, especially those raised in farms and hatcheries, are susceptible to enteric redmouth disease. A considerable amount of research has been conducted on redmouth disease, given its serious implications for rainbow trout farmers. The disease does not affect humans.[31]

Conservation

Populations of many rainbow trout subspecies, including anadromous forms (steelhead) of Oncorhynchus mykiss irideus, the coastal rainbow trout and Oncorhynchus mykiss gairdneri, the Columbia river redband trout have declined in their native ranges due to over harvest, habitat loss, disease, invasive species, pollution and hybridization with other subspecies. Some introduced populations, once healthy, have declined for the same reasons. Some populations of rainbow trout, particularly anadromous forms within their native range have been classified as endangered, threatened or species of special concern by federal or state agencies.[33] Rainbow trout, and subspecies thereof, are currently an U.S. Environmental Protection Agency-approved indicator species for acute fresh water toxicity testing.[34]

Steelhead declines

Steelhead populations in parts of its native range have declined due to a variety of human and natural causes. While populations in Alaska and along the British Columbia coast are considered healthy, populations in Kamchatka and some populations along the U.S. west coast are in decline. The U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service has 15 identified distinct population segments (DPS), in Washington, Oregon and California. Eleven of these DPS are listed under the U.S. Endangered Species Act, ten as threatened and one as endangered.[35] One DPS on the Oregon Coast is designated a U.S. Species of Concern.[36][37]

The Southern California DPS, which is listed as endangered as of 2011, has been impacted by habitat loss due to dams, confinement of streams in concrete channels, water pollution, groundwater pumping, urban heat island effects, and other byproducts of urbanization.[38]

Steelhead in the Kamchatka peninsula are considered threatened by over harvest, particularly from poaching and potential development and are listed in the Red Data Book of Russia that documents rare and endangered species.[39]

Hatchery stocking influence

Several studies have shown almost all California coastal steelhead are of native origin, despite over a century of hatchery stocking. Genetic analysis shows that South Central California Coast DPS and Southern California DPS from Malibu Creek north, and including the San Gabriel River, Santa Ana River and San Mateo Creek, are not hatchery strains. However, steelhead from Topanga Creek and the Sweetwater River were partly, and from San Juan Creek completely, of hatchery origin.[40] Genetic analysis has also shown the steelhead in the streams of the Santa Clara County and Monterey Bay basins are not of hatchery origin, including the Coyote Creek, Guadalupe River, Pajaro River, Permanente Creek, Stevens Creek, San Francisquito Creek, San Lorenzo River, and San Tomas Aquino Creek basins.[41] Natural waterfalls and two major dams have isolated Russian River steelhead from freshwater rainbow trout forms above the impassable barriers; however, a recent genetic study of fin samples collected from steelhead at 20 different sites both above and below passage barriers in the watershed found that despite the fact that 30 million hatchery trout were stocked in the river from 1911 to 1925, the steelhead remain of native and not hatchery origin.[42]

Hatcheries have also been demonstrated to present a risk to wild steelhead populations. Releases of conventionally reared hatchery steelhead pose ecological risks to pre-existing wild steelhead populations. Hatchery steelhead are typically larger than the wild forms, and can displace wild-form juveniles from optimal habitats. Dominance of hatchery steelhead for optimal microhabitats within streams may reduce wild steelhead survival as a result of reduced foraging opportunity and increased rates of predation.[43]

Hybridization and habitat loss

Rainbow trout primarily from hatchery raised Coastal rainbow trout subspecies (Oncorhynchus mykiss irideus) introduced into waters inhabited with cutthroat trout will breed with cutthroats and produce fertile hybrids called cutbows.[44] Such introductions into the ranges of Redband trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss gairdneri, newberrii, and stonei), have severely reduced the range of pure stocks of these subspecies making them Species of Concern in their respective ranges.[45]

Within the range of the Kern river golden trouts of Southern California, hatchery bred rainbows introduced into the Kern river have diluted the genetic purity of the Kern River rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss gilberti) and Golden trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss aguabonita) through intraspecific and interspecific breeding.[46]

The Beardslee trout, (Oncorhynchus mykiss irideus var. beardsleei), a genetically unique lake-dwelling variety of the coastal rainbow trout that is isolated in Lake Crescent (Washington), is threatened by the loss of its only spawning grounds in the Lyre River to siltation and other types of habitat degradation.[7]

Invasive species and disease

Whirling disease

Myxobolus cerebralis is a myxosporean parasite of salmonids (salmon, trout, and their allies) that causes whirling disease in farmed salmon and trout and also in wild fish populations. It was first described in rainbow trout in Germany a century ago, but its range has spread and it has appeared in most of Europe (including Russia), the United States, South Africa[47] and other countries. In the 1980s, M. cerebralis was found to require a tubificid oligochaete (a kind of segmented worm) to complete its life cycle.[48] The parasite infects its hosts with its cells after piercing them with polar filaments ejected from nematocyst-like capsules.[48]

Although originally a mild pathogen of brown trout in central Europe and other salmonids in northeast Asia, the spread of the rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) has greatly increased the impact of this parasite. Having no innate immunity to M. cerebralis, rainbow trout are particularly susceptible, and can release so many spores that even more resistant species in the same area, such as S. trutta, can become overloaded with parasites and incur 80%–90% mortalities. Where M. cerebralis has become well-established, it has caused decline or even elimination of whole cohorts of fish.[49][50]

M. cerebralis was first recorded in North America in 1956 in Pennsylvania[51] but until the 1990s, whirling disease was considered a manageable problem only affecting rainbow trout in hatcheries. It evidentually become established in natural waters of the Rocky Mountain states (Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, Montana, Idaho, New Mexico), where it is causing heavy mortalities in several sport fishing rivers. Some streams in the western United States lost 90% of their trout.[52] In addition, whirling disease threatens recreational fishing, which is important for the tourism industry, a key component of the economies of some U.S. western states. For example, "the Montana Whirling Disease Task Force estimated trout fishing generated US $300,000,000 in recreational expenditures in Montana alone".[53] Making matters worse, some of the fishes that M. cerebralis infects (bull trout, cutthroat trout, and anadromous forms of rainbow trout—steelhead) are already threatened or endangered, and the parasite could worsen their already precarious situations.[53]

New Zealand mud snail

While endemic to New Zealand, the New Zealand mud snail has spread widely and has become naturalised and an invasive species in many areas including: Australia, Tasmania, Asia (Japan,[54] in Garmat Ali River in Iraq since 2008[55]), Europe (since 1859 in England), and North America (USA and Canada: Thunder Bay in Ontario since 2001, British Columbia since July 2007[54]), most likely due to inadvertent human intervention.

The mud snail was first detected in the United States in Idaho's Snake River in 1987, the mudsnail has since spread to the Madison River, Firehole River, and other watercourses around Yellowstone National Park; samples have been discovered throughout the western United States.[56] Although the exact means of transmission is unknown, it is likely that it was introduced in water transferred with live game fish and has been spread by ship ballast or contaminated recreational equipment such as wading gear.[57]

Didymo

Didymosphenia geminata, commonly known as didymo or rock snot, is a species of diatom that produces nuisance growths in freshwater rivers and streams, with consistently cold water temperatures.[58] In New Zealand, invasive didymo can form large mats on the bottom of rivers and streams in late Winter. It is not considered a significant human health risk, but it can affect stream habitats and sources of food for fish, including rainbow trout, and make recreational activities unpleasant.[59] Even though it is native in North America, it is considered a nuisance organism or invasive species.[60]

Redmouth disease

Enteric redmouth disease, or simply redmouth disease is a bacterial infection of freshwater and marine fish caused by the pathogen Yersinia ruckeri. It is primarily found in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and other cultured salmonids. The disease is characterized by subcutaneous hemorrhaging of the mouth, fins, and eyes. It is most commonly seen in fish farms with poor water quality. Redmouth disease was first discovered in Idaho rainbow trout in the 1950s.[61]

Advocacy groups

The following non-profit and government organizations have an advocacy mission for native rainbow trout and steelhead.

- California Trout—a non-profit organization whose mission is to protect and restore wild trout, steelhead, salmon and their waters throughout California.[62]

- Long Live the Kings - a non-profit organization committed to restoring wild salmon and steelhead to the waters of the Pacific Northwest.[63]

- Native Fish Society - the society advocates for the recovery of wild, native fish and promotes the stewardship of the habitats that sustain them.[64]

- Steelhead Society of British Columbia - the society advocates for the health of all wild salmonids and wild rivers in British Columbia.[65]

- Trout Unlimited - a non-profit organization dedicated to the conservation of freshwater streams, rivers, and associated upland habitats for trout, salmon, other aquatic species, and people.[66]

- Wild Fish Conservancy Northwest - a non-profit dedicated to the recovery and conservation of the Northwest's wild-fish ecosystems.[67]

- Wild Salmon Center - Kamchatka Steelhead Project - a 20-year (1994–2014) scientific program to study and conserve the present condition of Kamchatkan steelhead (mikizha), a species listed in the Red Book of Russia.[68]

- Wild Steelhead Coalition - a non-profit dedicated to increasing the return of wild steelhead to the waters of the West Coast [69]

Uses

Fishing

Rainbow trout and steelhead are a highly regarded game fish. A number of angling methods are common. Rainbow trout are a popular target for fly fishers. The use of lures presented via spinning, casting or trolling techniques is a common method for anglers. Rainbow trout can also be caught on various live and dead natural baits. The International Game Fish Association recognizes the world record for rainbow trout was caught on Saskatchewan's Lake Diefenbaker by Sean Konrad on September 5, 2009. The fish weighed 48 pounds (22 kg). It was a genetically modified hatchery escapee.[70] Many anglers consider the rainbow trout the hardest fighting trout species, as this fish is known for leaping when hooked and putting up a powerful fight.[71] It is considered one of the top five sport fish in North American and the most important game fish west of the Rocky Mountains.[17]

There are tribal commercial fisheries for steelhead in Puget Sound, the Washington coast and in the Columbia River but they are not without controversy over the over harvesting of native stocks.[72]

These highly desirable life cycle and sporting qualities of the rainbow trout resulted in it being introduced to many countries around the world by or at the behest of sport fishermen. Many of these introductions have resulted in environmental and ecological problems as the introduced rainbow trout disrupt local ecosystems, outcompete and or eat indigenous fishes.[73] Other introductions to support sport angling in waters either devoid of fish or with seriously depleted native stocks, have created world class fisheries such as in the Firehole River in Yellowstone National Park [74] and in the Great Lakes.[75]

As food

Rainbow trout is popular in Western cuisine and is consumed as caught wild or from farmed fish. It has tender flesh and a mild, somewhat nutty flavor. Farmed trout and trout taken from certain lakes have a pronounced earthy flavor which some people find unappealing. Wild rainbow trout that eat scuds (freshwater shrimp), aquatic insects and crayfish are the most appealing. Farmed trout and some populations of wild trout, especially anadromous steelhead, have reddish or orange flesh as a result of high astaxanthin levels in their diets. Astaxanthin is a powerful antioxidant that may be from a natural source or synthetically produced trout feed. The color and flavor of the flesh is entirely dependent of the diet and freshness of the trout. Rainbow trout grown for human consumption may be called a variety of names for marketing purposes, including steelhead.[76]

Notes

- ^ "Symbols of Washington State". Washington State Legislature. Retrieved 2013-11-29.

- ^ "Invertebrate Zoology and Geology". California Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 2013-12-16.

- ^ Robert J. Behnke (1966). "Relationships of the Far Eastern Trout, Salmo mykiss Walbaum". Copeia. 1966 (2): 346–348. JSTOR 1441145.

- ^ "The Classification and Scientific Names of Rainbow and Cutthroat Trouts". Fisheries. 14 (1). American Fisheries Society: 4–10. 1989.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ a b Behnke, Robert J. (2002). "Genus Oncorhynchus". Trout and Salmon of North America. The Free Press. pp. 10–21. ISBN 0-7432-2220-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Behnke, Robert J. (2002). "Rainbow and Redband Trout". Trout and Salmon of North America. The Free Press. pp. 65–122. ISBN 0-7432-2220-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Meyer, J. (2002). "Summary of fisheries and limnological data for Lake Crescent, Washington". Olympic National Park Report. Port Angeles, WA: National Park Service.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Status of the Athabasca Rainbow Trout Oncorhynchus mykiss in Alberta" (PDF). Government of Alberta-Fish and Wildlife Division. Retrieved 2013-11-29.

- ^ John McCoy (2013-05-11). "50 years later, golden rainbows still 'a treat' for Mountain State fishermen". Saturday Gazette Mail.

- ^ a b c "Golden Rainbow Trout". Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission FAQ. Retrieved 2013-11-28.

- ^ "Golden Rainbow Trout". Retrieved 2013-11-28.

- ^ "Questions and Answers about the Fin Clip Fishery in Hills Creek Reservoir" (PDF). Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. Retrieved 2013-12-01.

- ^ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Oncorhynchus mykiss". FishBase. February 2006 version.

- ^ State of Alaska, Department of Fish and Game. "Steelhead/Rainbow Trout Species Profile". Retrieved 2013-08-26.

- ^ "Chefs Cherish Ocean Trout" (PDF). BrandTasmania.com. Retrieved 2013-11-28.

- ^ "Ontario-Great Lakes Area Fact Sheets Rainbow Trout". Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Retrieved 2013-11-28.

- ^ a b "Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss)" (PDF). U.S. Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 2013-12-16.

- ^ "Trout Streams Program in Kentucky for 2012" (PDF). Kentucky Department of Wildlife and Resources. Retrieved 2013-11-28.

- ^ "BC Fish Facts-Steelhead" (PDF). British Columbia Ministry of Fisheries. Retrieved 2013-11-28.

- ^ Haverson, Anders (2010). "As Many Different States as Possible". A Entirely Synthetic Fish: How Rainbow Trout Beguiled America and Overran the World. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300140873.

- ^ "A Century of Fish Conservation (1871–1971)". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 2013-11-28.

- ^ About Trout: The Best of Robert J. Behnke from Trout Magazine. Globe Pequot. 2007. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-1-59921-203-6. Retrieved 2011-05-03.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ "Fish and Aquatic Conservation". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 2013-11-28.

- ^ "Conservation-Salmon Hatcheries Overview". Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. Retrieved 2013-11-28.

- ^ Jason Frye. "The Cherokee Tribal Fish Hatchery". Ourstate.com. Retrieved 2013-11-28.

- ^ "trout profile". Agricultural Resource Marketing Center. Retrieved 2013-11-29.

- ^ "Farmed Rainbow Trout / Steelhead Salmon". Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. Retrieved 2013-11-29.

- ^ "Nonindigenous Aquatic Species-Rainbow Trout". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 2013-11-29.

- ^ Cowx, I.G. Cultured Aquatic Species Information Programme Oncorhynchus mykiss Walbaum, 1792 (Salmonidae) Rainbow Trout Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations Fisheries and Aquaculture Department (online), Rome, Updated 2005-06-15, Retrieved 2010-09-27.

- ^ a b "Species Fact Sheets:Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum, 1792)". Rome: FAO. Retrieved 2009-05-09.

- ^ "Enteric Redmouth Disease of Salmonids LSC". Fish Disease Leaflet 82. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1990. Archived from the original on 2009-06-16.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ "Fact Sheet-Oncorhynchus mykiss". U.S. Geological Survey Non-indigenous aquatic species. Retrieved 2013-11-30.

- ^ "Results of Species Search-Oncorhynchus mykiss". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 2013-11-29.

- ^ "EPA Whole Effluent ToxUnited States Environmental Protection Agencyicity". Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 2013-11-29.

- ^ "Steelhead Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss)". NOAA Fisheries, Office of Protected Resources. Retrieved 2013-11-28.

- ^ "Species Profile for steelhead (Oncorhynchus (=salmo) mykiss)". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 2013-11-29.

- ^ "Appendix D Evolutionarily Significant Units, Critical Habitat, and Essential Fish Habitat" (PDF). California Department of Water Resources. Retrieved 2013-11-29.

- ^ "South-Central/Southern California Coast Steelhead Recovery Planning Domain 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation of Southern California Coast Steelhead Distinct Population Segment" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2011. Retrieved 2013-12-03.

- ^ Guido Rahr III. "Bountiful Breed-Kamchatka Siberia's Forbidden Wilderness". PBS.org. Retrieved 2013-12-04.

- ^ "Population genetic structure and ancestry of Oncorhynchus mykiss populations above and below dams in south-central California" (PDF). Conservation Genetics: 1321–1336. 2009. Retrieved 2011-06-11.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Population genetics of Oncorhynchus mykiss in the Santa Clara Valley Region, Final Report to the Santa Clara Valley Water District (Report). Santa Clara Valley Water District. 2008-03. pp. 1–54.

{{cite report}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ "Population structure and genetic diversity of trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) above and below natural and man-made barriers in the Russian River, California" (PDF). Conservation Genetics: 437–454. 2007. Retrieved 2011-06-12.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ McMichael, G. A., T. N. Pearsons, and S. A. Leider. 1999. Behavioral interactions among hatchery-reared steelhead smolts and wild Oncorhynchus mykiss in natural streams. North American Journal of Fisheries Management 19: 948–956

- ^ "Weight, Length, and Growth in Cutbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss x clarkii)". Nature Precedings. 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ "Montana's Redband Trout". Montana Outdoors. Retrieved 2013-11-29.

- ^ Behnke, Robert J. "Trouts of the Upper Kern River Basin, California, with Reference to Systematics and Evolution of Western North American Salmo".

- ^ Bartholomew, J.L. and Reno, P.W. (2002). The history and dissemination of whirling disease. American Fisheries Society Symposium 29: 3–24.

- ^ a b Markiw, M.E. (1992). Salmonid Whirling disease. Fish and Wildlife Leaflet 17: 1–3. [1]

- ^ Nehring, R.B. (1996). Whirling Disease In Feral Trout Populations In Colorado. In E.P. Bergersen And B.A.Knoph (eds.), Proceedings: Whirling Disease Workshop––where Do We Go From Here? Colorado Cooperative Fish And Wildlife Research Unit, Fort Collins. p. 159.

- ^ Vincent, E.R. (1996). Whirling Disease—the Montana Experience, Madison River. In, E.P. Bergersen And B.A.Knoph (eds.), Proceedings: Whirling Disease Workshop—where Do We Go From Here? Colorado Cooperative Fish And Wildlife Research Unit, Fort Collins. p. 159.

- ^ Bergersen, E.P., and Anderson, D.E. (1997). The distribution and spread of Myxobolus cerebralis in the United States. Fisheries 22 (8): 6–7.

- ^ Tennyson, J. Anacker, T. & Higgins, S. (January 13, 1997). Scientific breakthrough helps combat trout disease. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Whirling Disease Foundation News Release.[2]

- ^ a b Gilbert, M. A.; Granath, W. O. Jr. (2003). "Whirling disease and salmonid fish: life cycle, biology, and disease". Journal of Parasitology. 89 (4): 658–667. JSTOR 3285855.

- ^ a b Timothy M. Davidson, Valance E. F. Brenneis, Catherine de Rivera, Robyn Draheim & Graham E. Gillespie. Northern range expansion and coastal occurrences of the New Zealand mud snail Potamopyrgus antipodarum (Gray, 1843) in the northeast Pacific (PDF). Aquatic Invasions (2008), Volume 3, Issue 3: 349-353.

- ^ Murtada D. Naser & Mikhail O. Son. 2009. First record of the New Zealand mud snail Potamopyrgus antipodarum (Gray 1843) from Iraq: the start of expansion to Western Asia? (PDF). Aquatic Invasions, Volume 4, Issue 2: 369-372, DOI 10.3391/ai.2009.4.2.11.

- ^ Benson, A.J., Kipp, R.M., Larson, J. & Fusaro, A. (2013). "Potamopyrgus antipodarum". USGS Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database. U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 2013-05-25.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Biology". New Zealand mudsnails in the Western USA. Montana State University. Retrieved 2006-05-04.

- ^ "DPIPWE - Didymo (Rock Snot)". Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment(Dpiw.tas.gov.au). 2013-11-04. Retrieved 2013-12-01.

- ^ Biosecurity New Zealand (2007). "Is didymo an exotic species?". Biosecurity New Zealand. Retrieved 2013-12-01.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Invasive Aquatic Species-Didymo". U.S. Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 2013-12-16.

- ^ "MFR Paper 1296 Enteric Redmouth Disease (Haggerman Strain)" (PDF). Marine Fisheries Review. 40 (3). March 1978.

- ^ "California Trout-About us". caltrout.org. Retrieved 2013-12-01.

- ^ "Long Live the Kings - About us". www.lltk.org. Retrieved 2013-12-01.

- ^ "Mission statement Native Fish Society". nativefishsociety.org. Retrieved 2013-12-01.

- ^ "About us - The Steelhead Society of British Columbia". www.steelheadsociety.org. Retrieved 2013-12-01.

- ^ Washabaugh, William and Catherine (2000). Deep Trout: Angling in Popular Culture. Oxford, UK: Berg. p. 119. ISBN 185973393X.

- ^ "Wild Fish Conservancy Northwest". wildfishconservancy.org. Retrieved 2013-12-01.

- ^ "Steelhead Project Report". www.wildsalmoncenter.org. Retrieved 2013-12-01.

- ^ "WSC About us". wildsteelheadcoalition.org. Retrieved 2013-12-01.

- ^ Brandon Keim. "48-Pound Trout: World Record or Genetic Cheat?". Wired.com. Retrieved 2013-11-29.

- ^ Waterman, Charles F. (1971). The Fisherman's World. New York: Random House. p. 57. ISBN 0-394-41099-8.

- ^ John Stellmon (2008). "Under the Guise of 'Treaty Rights:' The Nez Perce Tribe of Idaho, Steelhead, and Gillnetting". Public Land and Resources Law Review. 29.

- ^ "100 of the World's Worst Invasive Alien Species". Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG) of the IUCN Species Survival Commission. Retrieved 2013-11-28.

- ^ Brooks, Charles E. (1979). The Living River-A Fisherman's Intimate Profile of the Madison River Watershed—Its History, Ecology, Lore and Angling Opportunities. Garden City, NJ: Nick Lyons Books. pp. 56–59. ISBN 0-385-15655-3.

- ^ "Fishing New York's Great Lakes". New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Retrieved 2013-11-28.

- ^ Jay Harlow. "Rainbow Trout". Sallybernstein.com. Retrieved 2013-11-28.

Further reading

- Combs, Trey (1976). Steelhead Fly Fishing and Flies. Portland, Oregon: Frank Amato. ISBN 0-936608-03-X.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Combs, Trey (1991). Steelhead Fly Fishing. New York: Lyons and Burford Publishers. ISBN 1-55821-119-5.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Gerlach, Rex (1988). Fly Fishing for Rainbows-Strategies and tactics for North America's Favorite Trout. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-0624-9.

- Halverson, Anders (2010) An Entirely Synthetic Fish: How Rainbow Trout Beguiled America and Overran the World Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-14088-0. Review Interviews

- Marshall, Mel (1973). Steelhead. New York: Winchester Press. ISBN 0-87691-093-2.

- McClane, A. J. (1984). "Rainbow Trout and Steelhead". McClane's Game Fish of North America. New York: Times Books. pp. 54–93. ISBN 0-8129-1134-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - McDermand, Charles (1946). Waters of the Golden Trout Country. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons.

- Montaigne, Fen (1998). "Kamchatka". Reeling in Russia. New York: St. Martins Press. pp. 251–270. ISBN 0-312-18595-2.

- Scott and Crossman (1985) Freshwater Fishes of Canada. Bulletin 184. Fisheries Research Board of Canada. Page 189. ISBN 0-660-10239-0

- Walden, Howard T. 2nd (1964). "Rainbow, Cutthroat, and Golden Trout". Familiar Freshwater Fishes of America. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers. pp. 14–33.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

External links

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Oncorhynchus mykiss". FishBase. February 2006 version.

- "Oncorhynchus mykiss". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 2006-01-30.

- Oncorhynchus

- Cold water fish

- Fish of the Pacific Ocean

- Fish of the Western United States

- Fish of the Great Lakes

- Fauna of the Rocky Mountains

- Fauna of Canada

- Fish of Pakistan

- Introduced freshwater fish of Australia

- Introduced freshwater fish of New Zealand

- Introduced freshwater fish of South Africa

- Introduced freshwater fish of Chile

- Introduced freshwater fish of Argentina

- Animals described in 1792

- Invasive fish species

- Commercial fish

- Fly fishing target species