Quinolone

The quinolones are a family of synthetic broad-spectrum antibacterial drugs.[1][2][3]

The first generation of quinolones began with the introduction of nalidixic acid in 1962 for treatment of urinary tract infections in humans.[4] Nalidixic acid was discovered by George Lesher and coworkers in a distillate during an attempt at chloroquine synthesis.[5] Quinolones exert their antibacterial effect by preventing bacterial DNA from unwinding and duplicating (please see the Mechanism of Action section for details).[6] The majority of quinolones in clinical use belong to the subset fluoroquinolones, which have a fluorine atom attached to the central ring system, typically at the 6-position or C-7 position.

Medical uses

Fluoroquinolones are broad-spectrum antibiotics (effective for both gram negative and gram positive bacteria) that play an important role in treatment of serious bacterial infections, especially hospital-acquired infections and others in which resistance to older antibacterial classes is suspected. Because the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics encourages the spread of multidrug resistant strains and the development of Clostridium difficile infections, treatment guidelines from the Infectious Disease Society of America, the American Thoracic Society, and other professional organizations recommend minimizing the use of fluoroquinolones and other broad-spectrum antibiotics in less severe infections and in those in which risk factors for multidrug resistance are not present.

Fluoroquinolones are featured prominently in the The American Thoracic Society guidelines for the treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia.[7] The Society recommends fluoroquinolones not be used as a first-line agent for community-acquired pneumonia,[8] instead recommending macrolide or doxycycline as first-line agents. The Drug-Resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae Working Group recommends fluoroquinolones be used for the ambulatory treatment of community-acquired pneumonia only after other antibiotic classes have been tried and failed, or in those with demonstrated drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae.[9]

Fluoroquinolones are often used for genitourinary infections, and are widely used in the treatment of hospital-acquired infections associated with urinary catheters. In community-acquired infections, they are recommended only when risk factors for multidrug resistance are present or after other antibiotic regimens have failed. However, for serious acute cases of pyelonephritis or bacterial prostatitis where the patient may need to be hospitalised, fluoroquinolones are recommended as first-line therapy.[10]

Due to sickle-cell disease patients being at increased risk for developing osteomyelitis from the Salmonella genus, fluoroquinolones are the "drugs of choice" due to their ability to enter bone tissue without chelating it as tetracyclines are known to do.

Adverse effects

In general, fluoroquinolones are well tolerated, with most side effects being mild to moderate.[11] On occasion, serious adverse effects occur.[12]Common side effects include gastrointestinal effects such as nausea, vomiting and diarrhea, as well as headache and insomnia.

The overall rate of adverse events in patients treated with fluoroquinolones is roughly similar to that seen in patients treated with other antibiotic classes.[13][14][15][16] A U.S. Centers for Disease Control study found patients treated with fluoroquinolones experienced adverse events severe enough to lead to an emergency department visit more frequently than those treated with cephalosporins or macrolides, but less frequently than those treated with penicillins, clindamycin, sulfonamides, or vancomycin.[17]

Post-marketing surveillance has revealed a variety of relatively rare but serious adverse effects that are associated with all members of the fluoroquinolone antibacterial class. Among these, tendon problems and exacerbation of the symptoms of the neurological disorder myasthenia gravis are the subject of "black box" warnings in the United States. The most severe form of tendonopathy associated with fluoroquinolone administration is tendon rupture, which in the great majority of cases involves the Achilles tendon. Younger people typically experience good recovery, but permanent disability is possible, and is more likely in older patients.[18] The overall frequency of fluoroquinolone-associated Achilles tendon rupture in patients treated with ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin is has been estimated at 17 per 100,000 treatments.[19][20] Risk is substantially elevated in the elderly and in those with recent exposure to topical or systemic corticosteroid therapy. Simultaneous use of corticosteroids is present in almost one-third of quinolone-associated tendon rupture.[21] Tendon damage may manifest during, as well as up to a year after fluoroquinolone therapy has been completed.[22]

FQs prolong the QT interval by blocking voltage-gated potassium channels.[23] Prolongation of the QT interval can lead to torsades de pointes, a life threatening arrhythmia, but in practice this appears relatively uncommon in part because the most widely prescribed fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin) only minimally prolong the QT interval.[24]

Clostridium difficile associated diarrhea may occur in connection with the use of any antibacterial drug, especially those with a broad spectrum of activity such as clindamycin, cephalosporins, and fluoroquinolones. Fluoroquinoline treatment is associated with risk that is simlar to[25] or less [26][27] than that associated with broad spectrum cephalosporins.

Studies examining nervous system effects have estimated that neurotoxicity occurs in approximately 1% to 4.4% of patients taking FQs, with serious adverse effects occurring less than 0.5% of the time.[24] The most important of these may be peripheral neuropathy, which can be permanent.[28] Other nervous system effects include insomnia, restlessness, and rarely, seizure, convulsions, and psychosis[29] Other rare and serious adverse events have been observed with varying degrees of evidence for causation.[30][31][32][33]

Events that may occur in acute overdose are rare, and include renal failure and seizure.[34] Susceptible groups of patients, such as children and the elderly, are at greater risk of adverse reactions during therapeutic use.[11][35][36]

Contraindications

Quinolones are contraindicated if a patient has epilepsy, QT prolongation, pre-existing CNS lesions, CNS inflammation or suffered a stroke.[12] There are safety concerns of fluoroquinolone use during pregnancy and, as a result, are contraindicated except for when no other safe alternative antibiotic exists.[37] However, one meta-analysis looking at the outcome of pregnancies involving Quinolone use in the first trimester found no increased risk of malformations.[38] They are also contraindicated in children due to the risks of damage to the musculoskeletal system.[39] Their use in children is not absolutely contraindicated, however. For certain severe infections where other antibiotics are not an option, their use can be justified.[40] Quinolones should also not be given to people with a known hypersensitivity to the drug.[41][42] Quinolone antibiotics should not be administered to patients who are dependent on benzodiazepines, since they compete directly with benzodiazepines at the GABA-A receptor, acting as a competitive antagonist and thus possibly precipitating a severe acute and potentially fatal withdrawal effect.[43][44][45]

Pharmacology

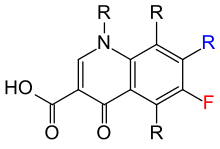

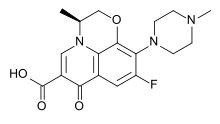

The basic pharmacophore, or active structure, of the fluoroquinolone class is based upon the quinoline ring system.[46] The addition of the fluorine atom at C6 distinguishes the successive-generation fluoroquinolones from the first-generation quinolones. The addition of the C6 fluorine atom has since been demonstrated to not be required for the antibacterial activity of this class (circa 1997).[47]

Various substitutions made to the quinoline ring resulted in the development of numerous fluoroquinolone drugs available today. Each substitution is associated with a number of specific adverse reactions, as well as increased activity against bacterial infections, whereas the quinoline ring, in and of itself, has been associated with severe and even fatal adverse reactions.[48]

Mechanism of action

Fluoroquinolones inhibit the topoisomerase II ligase domain, leaving the two nuclease domains intact. This modification, coupled with the constant action of the topoisomerase II in the bacterial cell, leads to DNA fragmentation via the nucleasic activity of the intact enzyme domains. Recent evidence has shown eukaryotic topoisomerase II is also a target for a variety of quinolone-based drugs. Thus far, most of the compounds that show high activity against the eukaryotic type II enzyme contain aromatic substituents at their C-7 positions.[49][50]

Fluoroquinolones can enter cells easily via porins and, therefore, are often used to treat intracellular pathogens such as Legionella pneumophila and Mycoplasma pneumoniae. For many gram-negative bacteria, DNA gyrase is the target, whereas topoisomerase IV is the target for many gram-positive bacteria. Some compounds in this class have been shown to inhibit the synthesis of mitochondrial DNA.[51][52][53][54][55][56][57]

Mechanism of toxicity

The mechanisms of the toxicity of fluoroquinolones has been attributed to their interactions with different receptor complexes, such as blockade of the GABAa receptor complex within the central nervous system, leading to excitotoxic type effects[12] and oxidative stress.[58]

Interactions

Theophylline, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and corticosteroids enhance the toxicity of fluoroquinolones.[59][60][61]

Products containing multivalent cations, such as aluminium- or magnesium-containing antacids and products containing calcium, iron, or zinc, invariably result in marked reduction of oral absorption of fluoroquinolones.[62] Taking colloidal silver along with several versions of quinolones might decrease how much antibiotic the body absorbs.[63]

Other drugs that interact with fluoroquinolones include antacids, sucralfate, probenecid, cimetidine, warfarin, antiviral agents, phenytoin, cyclosporine, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and cycloserine.[61]

Many fluoroquinolones, especially ciprofloxacin, inhibit the cytochrome P450 isoform CYP1A2.[64] This inhibition causes an increased level of drugs that are metabolized by this enzyme. This includes antidepressants such as amitriptyline and imipramine, clozapine (an atypical antipsychotic), caffeine, olanzapine (an atypical antipsychotic), ropivacaine (a local anaesthetic), theophylline (a xanthine), and zolmitriptan (a serotonin receptor agonist).[64]

Antibiotic misuse and bacterial resistances

Resistance to quinolones can evolve rapidly, even during a course of treatment. Numerous pathogens, including Staphylococcus aureus, enterococci, and Streptococcus pyogenes now exhibit resistance worldwide.[65] Widespread veterinary usage of quinolones, in particular in Europe, has been implicated.[66]

Fluoroquinolones have been recommended to be reserved for the use in patients who are seriously ill and may soon require immediate hospitalization.[67] Though considered to be very important and necessary drugs required to treat severe and life-threatening bacterial infections, the associated antibiotic misuse remains unchecked, which has contributed to the problem of bacterial resistance. The overuse of antibiotics such as happens with children suffering from otitis media (ear infections) has given rise to a breed of super bacteria that are resistant to antibiotics entirely.[68]

For example, the use of the fluoroquinolones had increased threefold in an emergency room environment in the United States between 1995 and 2002, while the use of safer alternatives, such as macrolides, declined significantly.[69][70] Fluoroquinolones had become the most commonly prescribed class of antibiotics to adults in 2002. Nearly half (42%) of these prescriptions were for conditions not approved by the FDA, such as acute bronchitis, otitis media, and acute upper respiratory tract infection, according to a study supported in part by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.[70][71] In addition, they are commonly prescribed for medical conditions, such as acute respiratory illness, that are usually caused by viral infections.[72]

Within a recent study concerning the proper use of this class in the emergency rooms of two academic hospitals, 99% of these prescriptions were revealed to be in error. Out of the 100 total patients studied, 81 received a fluoroquinolone for an inappropriate indication. Out of these cases, 43 (53%) were judged to be inappropriate because another agent was considered first line, 27 (33%) because there was no evidence of a bacterial infection to begin with (based on the documented evaluation), and 11 (14%) because of the need for such therapy was questionable. Of the 19 patients who received a fluoroquinolone for an appropriate indication, only one patient of 100 received both the correct dose and duration of therapy.[73]

Three mechanisms of resistance are known.[74] Some types of efflux pumps can act to decrease intracellular quinolone concentration.[75] In Gram-negative bacteria, plasmid-mediated resistance genes produce proteins that can bind to DNA gyrase, protecting it from the action of quinolones. Finally, mutations at key sites in DNA gyrase or topoisomerase IV can decrease their binding affinity to quinolones, decreasing the drugs' effectiveness.

History

Nalidixic acid is considered to be the predecessor of all members of the quinolone family, including the second, third and fourth generations commonly known as fluoroquinolones. This first generation also included other quinolone drugs, such as pipemidic acid, oxolinic acid, and cinoxacin, which were introduced in the 1970s. They proved to be only marginal improvements over nalidixic acid.[76] Though it is generally accepted nalidixic acid is to be considered the first quinolone drug, this has been disputed over the years by a few researchers who believe chloroquine, from which nalidixic acid is derived, is to be considered the first quinolone drug, rather than nalidixic acid.

Since the introduction of nalidixic acid in 1962, more than 10,000 analogs have been synthesized, but only a handful have found their way into clinical practice.

- Advocacy Groups and Regulation:

In August 2013, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued a Safety Alert requiring drug labels and for all fluoroquinolone antibacterial drugs "be updated to better describe the serious side effect of peripheral neuropathy. This serious nerve damage potentially caused by fluoroquinolones may occur soon after these drugs are taken and may be permanent." Only those taken by mouth or injection were covered by the alert, while those used topically on the eyes and ears were not.

Several advocacy groups have petitioned the FDA to increase the prominence of adverse effect warnings on the labels of fluroquinolone antibacterials, and to withdraw others from the market.[77][78][79][80][81][82][83]

Legal status

Current litigation

A significant number of cases are pending before the United States District Court, District of Minnesota, involving the drug Levaquin. On 13 June 2008, a Judicial Panel On Multidistrict Litigation (MDL) granted the Plaintiffs’ motion to centralize individual and class-action lawsuits involving Levaquin in the District of Minnesota over objection of Defendants, Johnson and Johnson / Ortho McNeil.[84]

On 6 July 2009, the New Jersey Supreme Court had also designated litigation over Levaquin as a mass tort and has assigned it to an Atlantic County, N.J., judge. The suits charge the drug has caused Achilles tendon ruptures and other permanent damage.[85] Of a total of about 3400 cases, 845 were recently settled out of court after Johnson and Johnson prevailed in three of the first four cases to go to trial[86][87]

Several class action lawsuits had been filed in regards to the adverse reactions allegedly suffered by those exposed to ciprofloxacin during the anthrax scare of 2001.

Boxed warnings

In the US, the package insert for fluoroquinolone antibiotics includes a boxed warning of increased risk of developing tendonitis and tendon rupture in patients of all ages taking fluoroquinolones for systemic use. This risk is further increased in individuals over 60 years of age, taking corticosteroid drugs, and have received kidney, heart, or lung transplants. Another boxed warning says fluoroquinolones, due to their neuromuscular blocking activity, may exacerbate muscle weakness in persons with myasthenia gravis. Serious adverse events, including deaths and requirement for ventilatory support, have been reported in this group of patients. Avoidance of fluoroquinolones in patients with known history of myasthenia gravis is advised.[88]

A class-action lawsuit was filed on behalf of individuals alleging harm by the use of fluoroquinolones, as well as action by the consumer advocate group, Public Citizen.[89][84] Partly as a result of the efforts of Public Citizen, the FDA ordered boxed warnings on all fluoroquinolones, advising consumers of an enhanced risk of tendon damage.[90]

Generations

Researchers divide the quinolones into generations based on their antibacterial spectrum.[91][92] The earlier-generation agents are, in general, more narrow-spectrum than the later ones, but no standard is employed to determine which drug belongs to which generation. The only universal standard applied is the grouping of the nonfluorinated drugs found within this class (quinolones) within the 'first-generation' heading. As such, a wide variation exists within the literature dependent upon the methods employed by the authors.

- Some researchers group these drugs by patent dates[citation needed]

- Some by a specific decade (i.e., '60s, '70s, '80s, etc.)[citation needed]

- Others by the various structural changes[citation needed]

The first generation is rarely used today. Nalidixic acid was added to the OEHHA Prop 65 list as a carcinogen on 15 May 1998.[93] A number of the second-, third-, and fourth-generation drugs have been removed from clinical practice due to severe toxicity issues or discontinued by their manufacturers. The drugs most frequently prescribed today consist of Avelox (moxifloxacin), Cipro (ciprofloxacin), Levaquin (levofloxacin), and, to some extent, their generic equivalents.

First-generation

- cinoxacin (Cinobac) (discontinued by manufacturer)[94]

- nalidixic acid (NegGram, Wintomylon)[94]

- oxolinic acid (Uroxin)

- piromidic acid (Panacid)

- pipemidic acid (Dolcol)

- rosoxacin (Eradacil)

Second-generation

The second-generation class is sometimes subdivided into "Class 1" and "Class 2".[95]

- ciprofloxacin (Alcipro,Ciprobay, Cipro, Ciproxin)[94][96]

- enoxacin (Enroxil, Penetrex)[94]

- fleroxacin (Megalone, Roquinol)

- lomefloxacin (Maxaquin)[94]

- nadifloxacin (Acuatim, Nadoxin, Nadixa)

- norfloxacin (Lexinor, Noroxin, Quinabic, Janacin)[94][97]

- ofloxacin (Floxin, Oxaldin, Tarivid)[94]

- pefloxacin (Peflacine)

- rufloxacin (Uroflox)

Third-generation

Unlike the first- and second-generations, the third-generation is active against streptococci.[95]

- balofloxacin (Baloxin)

- grepafloxacin (Raxar) (removed from clinical use)

- levofloxacin (Cravit, Levaquin)

- pazufloxacin (Pasil, Pazucross)

- sparfloxacin (Zagam)

- temafloxacin (Omniflox) (removed from clinical use)[98]

- tosufloxacin (Ozex, Tosacin)

Fourth-generation

Fourth generation fluoroquinolones act at DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV.[99] This dual action slows development of resistance.

- clinafloxacin[96]

- gatifloxacin (Zigat, Tequin) (Zymar -opth.) (Tequin removed from clinical use)[100]

- gemifloxacin (Factive)

- moxifloxacin (Avelox,Vigamox)[94]

- sitafloxacin (Gracevit)

- trovafloxacin (Trovan) (removed from clinical use)[94][96]

- prulifloxacin (Quisnon)

In development

- delafloxacin — an anionic fluoroquinoline in clinical trials

- JNJ-Q2 — completed Phase II for MRSA

- nemonoxacin

Veterinary use

The quinolones have been widely used in agriculture, and several agents have veterinary, but not human, applications.

- danofloxacin (Advocin, Advocid) (for veterinary use)

- difloxacin (Dicural, Vetequinon) (for veterinary use)

- enrofloxacin (Baytril) (for veterinary use)

- ibafloxacin (Ibaflin) (for veterinary use)

- marbofloxacin (Marbocyl, Zenequin) (for veterinary use)

- orbifloxacin (Orbax, Victas) (for veterinary use)

- sarafloxacin (Floxasol, Saraflox, Sarafin) (for veterinary use)

However, the agricultural use of fluoroquinolones in the U.S. has been restricted since 1997, due to concerns over the development of antibiotic resistance.[101]

References

- ^ Andriole, VT The Quinolones. Academic Press, 1989.

- ^ Andersson, MI, MacGowan, AP. Development of the quinolones. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. (2003) 51, Suppl. S1, 1–11 DOI: 10.1093/jac/dkg212.

- ^ Ivanov DV, Budanov SV (2006). "[Ciprofloxacin and antibacterial therapy of respiratory tract infections]". Antibiot. Khimioter. (in Russian). 51 (5): 29–37. PMID 17310788.

- ^ sanofi-aventis U.S. LLC (2008). "NegGram Caplets (nalidixic acid, USP)" (PDF). USA: FDA.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Wentland MP: In memoriam: George Y. Lesher, Ph.D., in Hooper DC, Wolfson JS (eds): Quinolone antimicrobial agents, ed 2., Washington DC, American Society for Microbiology : XIII - XIV, 1993.

- ^ Hooper, DC. (2001). "Emerging mechanisms of fluoroquinolone resistance". Emerg Infect Dis. 7 (2): 337–41. doi:10.3201/eid0702.010239. PMC 2631735. PMID 11294736.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia". Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 171 (4): 388–416. 2005. doi:10.1164/rccm.200405-644ST. PMID 15699079.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A; et al. (2007). "Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults". Clin. Infect. Dis. 44 Suppl 2: S27–72. doi:10.1086/511159. PMID 17278083.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ MacDougall C, Guglielmo BJ, Maselli J, Gonzales R (2005). "Antimicrobial drug prescribing for pneumonia in ambulatory care". Emerging Infect. Dis. 11 (3): 380–4. doi:10.3201/eid1103.040819. PMC 3298265. PMID 15757551.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Liu, H.; Mulholland, SG. (2005). "Appropriate antibiotic treatment of genitourinary infections in hospitalized patients". Am J Med. 118 Suppl 7A (7): 14S–20S. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.05.009. PMID 15993673.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Owens RC, Ambrose PG (2005). "Antimicrobial safety: focus on fluoroquinolones". Clin. Infect. Dis. 41 Suppl 2: S144–57. doi:10.1086/428055. PMID 15942881.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c De Sarro A, De Sarro G (2001). "Adverse reactions to fluoroquinolones. an overview on mechanistic aspects". Curr. Med. Chem. 8 (4): 371–84. PMID 11172695.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) Cite error: The named reference "pmid11172695" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ "www.fda.gov".

- ^ Skalsky K, Yahav D, Lador A, Eliakim-Raz N, Leibovici L, Paul M (2013). "Macrolides vs. quinolones for community-acquired pneumonia: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 19 (4): 370–8. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03838.x. PMID 22489673.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Falagas ME, Matthaiou DK, Vardakas KZ (2006). "Fluoroquinolones vs beta-lactams for empirical treatment of immunocompetent patients with skin and soft tissue infections: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Mayo Clin. Proc. 81 (12): 1553–66. PMID 17165634.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Van Bambeke F, Tulkens PM (2009). "Safety profile of the respiratory fluoroquinolone moxifloxacin: comparison with other fluoroquinolones and other antibacterial classes". Drug Saf. 32 (5): 359–78. PMID 19419232.

- ^ Shehab N, Patel PR, Srinivasan A, Budnitz DS (2008). "Emergency department visits for antibiotic-associated adverse events". Clin. Infect. Dis. 47 (6): 735–43. doi:10.1086/591126. PMID 18694344.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kim GK (2010). "The Risk of Fluoroquinolone-induced Tendinopathy and Tendon Rupture: What Does The Clinician Need To Know?". J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 3 (4): 49–54. PMC 2921747. PMID 20725547.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Sode J, Obel N, Hallas J, Lassen A (2007). "Use of fluroquinolone and risk of Achilles tendon rupture: a population-based cohort study". Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 63 (5): 499–503. doi:10.1007/s00228-007-0265-9. PMID 17334751.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Owens RC, Ambrose PG (2005). "Antimicrobial safety: focus on fluoroquinolones". Clin. Infect. Dis. 41 Suppl 2: S144–57. doi:10.1086/428055. PMID 15942881.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Khaliq Y, Zhanel GG (2005). "Musculoskeletal injury associated with fluoroquinolone antibiotics". Clin Plast Surg. 32 (4): 495–502, vi. doi:10.1016/j.cps.2005.05.004. PMID 16139623.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Saint F, Gueguen G, Biserte J, Fontaine C, Mazeman E (2000). "[Rupture of the patellar ligament one month after treatment with fluoroquinolone]". Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot (in French). 86 (5): 495–7. PMID 10970974.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Heidelbaugh JJ, Holmstrom H (2013). "The perils of prescribing fluoroquinolones". J Fam Pract. 62 (4): 191–7. PMID 23570031.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Rubinstein E, Camm J (2002). "Cardiotoxicity of fluoroquinolones". J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 49 (4): 593–6. PMID 11909831.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Deshpande A, Pasupuleti V, Thota P; et al. (2013). "Community-associated Clostridium difficile infection and antibiotics: a meta-analysis". J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 68 (9): 1951–61. doi:10.1093/jac/dkt129. PMID 23620467.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Slimings C, Riley TV (2013). "Antibiotics and hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile infection: update of systematic review and meta-analysis". J. Antimicrob. Chemother. doi:10.1093/jac/dkt477. PMID 24324224.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Data Mining Analysis of Multiple Antibiotics in AERS".

- ^ "FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA requires label changes to warn of risk for possibly permanent nerve damage from antibacterial fluoroquinolone drugs taken by mouth or by injection".

- ^ Galatti L, Giustini SE, Sessa A; et al. (2005). "Neuropsychiatric reactions to drugs: an analysis of spontaneous reports from general practitioners in Italy". Pharmacol. Res. 51 (3): 211–6. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2004.08.003. PMID 15661570.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Babar, S. (2013). "SIADH Associated With Ciprofloxacin" (PDF). The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 47 (10). Sage Publishing: 1359-1363. doi:10.1177/1060028013502457. ISSN 1060-0280. Retrieved November 139,2013.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Rouveix, B. (2006). "[Clinically significant toxicity and tolerance of the main antibiotics used in lower respiratory tract infections]". Med Mal Infect. 36 (11–12): 697–705. doi:10.1016/j.medmal.2006.05.012. PMID 16876974.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Mehlhorn AJ, Brown DA (2007). "Safety concerns with fluoroquinolones". Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 41 (11): 1859–66. doi:10.1345/aph.1K347. PMID 17911203.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Jones SF, Smith RH (1997). "Quinolones may induce hepatitis". BMJ. 314 (7084): 869. doi:10.1136/bmj.314.7084.869. PMC 2126221. PMID 9093098.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Nelson, Lewis H.; Flomenbaum, Neal; Goldfrank, Lewis R.; Hoffman, Robert Louis; Howland, Mary Deems; Neal A. Lewin (2006). Goldfrank's toxicologic emergencies. New York: McGraw-Hill, Medical Pub. Division. ISBN 0-07-143763-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Iannini PB (2007). "The safety profile of moxifloxacin and other fluoroquinolones in special patient populations". Curr Med Res Opin. 23 (6): 1403–13. doi:10.1185/030079907X188099. PMID 17559736.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Farinas, Evelyn R (1 March 2005). "Consult: One-Year Post Pediatric Exclusivity Postmarketing Adverse Events Review" (PDF). USA: FDA. Retrieved 31 August 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Nardiello, S.; Pizzella, T.; Ariviello, R. (2002). "[Risks of antibacterial agents in pregnancy]". Infez Med. 10 (1): 8–15. PMID 12700435.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009 Apr;143(2):75-8. Epub 2009 Jan 31. The safety of quinolones--a meta-analysis of pregnancy outcomes. Bar-Oz B, Moretti ME, Boskovic R, O'Brien L, Koren G.

- ^ Noel, GJ.; Bradley, JS.; Kauffman, RE.; Duffy, CM.; Gerbino, PG.; Arguedas, A.; Bagchi, P.; Balis, DA.; Blumer, JL. (2007). "Comparative safety profile of levofloxacin in 2523 children with a focus on four specific musculoskeletal disorders". Pediatr Infect Dis J. 26 (10): 879–91. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e3180cbd382. PMID 17901792.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Leibovitz, E.; Dror, Yigal (2006). "The use of fluoroquinolones in children". Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 18 (1): 64–70. doi:10.1097/01.mop.0000192520.48411.fa. PMID 16470165.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Janssen Pharmaceutica (2008). "HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION" (PDF). USA: FDA.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Scherer, K.; Bircher, AJ. (2005). "Hypersensitivity reactions to fluoroquinolones". Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 5 (1): 15–21. doi:10.1007/s11882-005-0049-1. PMID 15659258.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Unseld E, Ziegler G, Gemeinhardt A; et al. (1990). "Possible interaction of fluoroquinolones with the benzodiazepine-GABAA-receptor complex". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 30: 63–70.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ John Girvan McConnell. Benzodiazepine tolerance, dependency, and withdrawal syndromes and interactions with fluoroquinolone antimicrobials. Br J Gen Pract. 2008 May 1; 58(550): 365–366.

- ^ Halliwell RF, Davey PG, Lambert JJ. Antagonism of GABAA receptors by 4-quinolones. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993;31:457–462.

- ^ Schaumann, R. (2007). "Activities of Quinolones Against Obligately Anaerobic Bacteria" (PDF). Anti-Infective Agents in Medicinal Chemistry (Formerly Current Medicinal Chemistry - Anti-Infective Agents). 6 (1). Bentham Science Publishers: 49–56.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Chang Y.H. (22 July 1997). "Novel 5-amino-6-methylquinolone antibacterials: A new class of non-6-fluoroquinolones". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 7 (14). Elsevier: 1875–1878. doi:10.1016/S0960-894X(97)00324-7.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ CANN HM, VERHULST HL (1961). "Fatal acute chloroquine poisoning in children". Pediatrics. 27 (1): 95–102. PMID 13690445.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Elsea, SH.; Osheroff, N.; Nitiss, JL. (1992). "Cytotoxicity of quinolones toward eukaryotic cells. Identification of topoisomerase II as the primary cellular target for the quinolone CP-115,953 in yeast" (pdf). J Biol Chem. 267 (19): 13150–3. PMID 1320012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Pommier, Y., Leo, E., Zhang, H., Marchand, C. 2010. DNA topoisomerases and their poisoning by anticancer and antibacterial drugs. Chem. Biol. 17: 421-433.

- ^ Bergan T. (1988). "Pharmacokinetics of fluorinated quinolones". Academic Press: 119–154.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bergan T (1985). "A review of the pharmacokinetics and tissue penetration of ciprofloxacin": 23–36.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Castora, FJ.; Vissering, FF.; Simpson, MV. (1983). "The effect of bacterial DNA gyrase inhibitors on DNA synthesis in mammalian mitochondria". Biochim Biophys Acta. 740 (4): 417–27. PMID 6309236.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kaplowitz, Neil (2005). "Hepatology highlights". Hepatology. 41 (2): 227. doi:10.1002/hep.20596.

- ^ Enzmann, H.; Wiemann, C.; Ahr, HJ.; Schlüter, G. (1999). "Damage to mitochondrial DNA induced by the quinolone Bay y 3118 in embryonic turkey liver". Mutat Res. 425 (2): 213–24. doi:10.1016/S0027-5107(99)00044-5. PMID 10216214.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Holden, HE.; Barett, JF.; Huntington, CM.; Muehlbauer, PA.; Wahrenburg, MG. (1989). "Genetic profile of a nalidixic acid analog: a model for the mechanism of sister chromatid exchange induction". Environ Mol Mutagen. 13 (3): 238–52. doi:10.1002/em.2850130308. PMID 2539998.

- ^ Suto, MJ.; Domagala, JM.; Roland, GE.; Mailloux, GB.; Cohen, MA. (1992). "Fluoroquinolones: relationships between structural variations, mammalian cell cytotoxicity, and antimicrobial activity". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 35 (25): 4745–50. doi:10.1021/jm00103a013. PMID 1469702.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Saint F, Salomon L, Cicco A, de la Taille A, Chopin D, Abbou CC (2001). "[Tendinopathy associated with fluoroquinolones: individuals at risk, incriminated physiopathologic mechanisms, therapeutic management]". Prog. Urol. (in French). 11 (6): 1331–4. PMID 11859676.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Moderate Interaction: Quinolones/Corticosteroids". Medscape. Retrieved 2 September 2008.

- ^ Cohen JS (2001). "Peripheral Neuropathy Associated with Fluoroquinolones" (PDF). Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 35 (12): 1540–7. doi:10.1345/aph.1Z429. PMID 11793615.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b "Fluoroquinolone Adverse Effects and Drug Interactions". Medscape. Retrieved 2 September 2008.

- ^ Fluoroquinolone Adverse Effects and Drug Interactions: Drug-Drug Interactions Author from: the Department of Pharmacy Practice, School of Pharmacy, University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Denver, Colorado. Retrieved on 17 December 2009

- ^ Cupp, Melanie Johns (2003). "Colloidal Silver". Forensic Science and Medicine: 87–90. doi:10.1007/978-1-59259-303-3_6. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Swedish environmental classification of pharmaceuticals Facts for prescribers (Fakta för förskrivare)

- ^ M Jacobs, Worldwide Overview of Antimicrobial Resistance. International Symposium on Antimicrobial Agents and Resistance 2005.

- ^ Nelson, JM.; Chiller, TM.; Powers, JH.; Angulo, FJ. (2007). "Fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter species and the withdrawal of fluoroquinolones from use in poultry: a public health success story" (PDF). Clin Infect Dis. 44 (7): 977–80. doi:10.1086/512369. PMID 17342653.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Jim Hoover, for Bayer Corporation, Alaska Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee 19 March 2004

- ^ Froom J, Culpepper L, Jacobs M; et al. (1997). "Antimicrobials for acute otitis media? A review from the International Primary Care Network". BMJ. 315 (7100): 98–102. doi:10.1136/bmj.315.7100.98. PMC 2127061. PMID 9240050.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ MacDougall C, Guglielmo BJ, Maselli J, Gonzales R (2005). "Antimicrobial drug prescribing for pneumonia in ambulatory care". Emerging Infect. Dis. 11 (3): 380–4. doi:10.3201/eid1103.040819. PMC 3298265. PMID 15757551.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Linder JA, Huang ES, Steinman MA, Gonzales R, Stafford RS (2005). "Fluoroquinolone prescribing in the United States: 1995 to 2002". The American Journal of Medicine. 118 (3): 259–68. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.09.015. PMID 15745724.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ K08 HS14563 and HS11313

- ^ Neuhauser, MM; Weinstein, RA; Rydman, R; Danziger, LH; Karam, G; Quinn, JP (2003). "Antibiotic resistance among gram-negative bacilli in US intensive care units: implications for fluoroquinolone use". JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association. 289 (7): 885–8. doi:10.1001/jama.289.7.885. PMID 12588273.

From 1995 to 2002, inappropriate antibiotic prescribing for acute respiratory infections, which are usually caused by viruses and thus are not responsive to antibiotics, declined from 61 to 49 percent. However, the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics such as the fluoroquinolones, jumped from 41 to 77 percent from 1995 to 2001. Overuse of these antibiotics will eventually render them useless for treating antibiotic-resistant infections, for which broad-spectrum antibiotics are supposed to be reserved.

- ^ Lautenbach E, Larosa LA, Kasbekar N, Peng HP, Maniglia RJ, Fishman NO (2003). "Fluoroquinolone utilization in the emergency departments of academic medical centers: prevalence of, and risk factors for, inappropriate use". Arch. Intern. Med. 163 (5): 601–5. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.5.601. PMID 12622607.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Robicsek A, Jacoby GA, Hooper DC (2006). "The worldwide emergence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance". Lancet Infect Dis. 6 (10): 629–40. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70599-0. PMID 17008172.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Morita Y, Kodama K, Shiota S, Mine T, Kataoka A, Mizushima T, Tsuchiya T (1998). "NorM, a Putative Multidrug Efflux Protein, of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Its Homolog in Escherichia coli". Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42 (7): 1778–82. PMC 105682. PMID 9661020.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Norris, S; Mandell, GL (1988). "The quinolones: history and overview". The quinolones: history and overview. San Diego: Academic Press Inc. pp. 1–22.

- ^ "Petition to Require a Warning on All Fluoroquinolone Antibiotics (HRG Publication #1399)". Public Citizen. 1 August 1996. Retrieved 27 December 2008.

- ^ "Public Citizen Petitions the FDA to Include a Black Box Warning on Fluoroquinolone Antibiotics (HRG Publication #1781)". Public Citizen. 29 August 2006. Retrieved 27 December 2008.

- ^ Public Citizen (3 January 2008). "In The United States District Court For The District Of Columbia" (PDF). USA: Carey & Danis, LLC.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Lisa Madigan (18 May 2005). "Office Of The Attorney General State Of Illinois, CITIZEN PETITION" (PDF). USA: FDA.

- ^ Joseph Baker (1 May 2006). "Petition to the FDA to Immediately Ban the Antibiotic Gatifloxacin (Tequin) (HRG Publication #1768)". USA: Public Citizen.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Letter to the Food and Drug Administration to immediately ban the antibiotic trovafloxacin (Trovan) (HRG Publication #1485)". USA: Public Citizen. 3 June 1999.

- ^ Larry D. Sasich, (9 June 1998). "Petition to the Food and Drug Administration to immediately stop the distribution of dangerous, misleading prescription drug information to the public. (HRG Publication #1442)". USA: Public Citizen.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ a b Judge John R. Tunheim. "Levaquin MDL". USA: US Courts. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- ^ Charles Toutant (6 July 2009). "Litigation Over Johnson & Johnson Antibiotic Levaquin Designated N.J. Mass Tort". New Jersey Law Journal.

- ^ "Levaquin MDL | United States District Court - District of Minnesota, United States District Court - District of Minnesota".

- ^ "Johnson & Johnson Settles 845 Levaquin Lawsuits - Businessweek".

- ^ Risk of fluoroquinolone-associated Myasthenia Gravis Exacerbation February 2011 Label Changes for Fluoroquinolones FDA, online access 16 March 2011

- ^ "Public Citizen Warns of Cipro Dangers". USA: Consumer affairs. 30 August 2006. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- ^ "FDA orders 'black box' label on some antibiotics". CNN. 8 July 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2008.

- ^ Ball P (2000). "Quinolone generations: natural history or natural selection?". J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 46 Suppl T1 (Supplement 3): 17–24. PMID 10997595.

- ^ "New Classification and Update on the Quinolone Antibiotics - May 1, 2000 - American Academy of Family Physicians". Retrieved 18 March 2008.

- ^ [Nalidixic Acid, case number 389-08-02, listing mechanism AB, NTP (1989b)]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Quinolones: A Comprehensive Review - February 1, 2002 - American Family Physician".

- ^ a b Oliphant CM, Green GM (2002). "Quinolones: a comprehensive review". Am Fam Physician. 65 (3): 455–64. PMID 11858629.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Paul G. Ambrose (1 March 2000). "Clinical Usefulness Of Quinolones". Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. Medscape.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ The European Medicines Agency (24 July 2008). "EMEA Restricts Use of Oral Norfloxacin Drugs in UTIs". Doctor's Guide.

- ^ Paul G. Ambrose (1 March 2000). "New Antibiotics in Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine: Classification Of Quinolones By Generation". USA: Medscape.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Gupta (2009). Clinical Ophthalmology: Contemporary Perspectives, 9/e. Elsevier India. pp. 112–. ISBN 978-81-312-1680-4. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

- ^ Schmid, Randolph E. (1 May 2006). "Drug Company Taking Tequin Off Market". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 25 November 2007. Retrieved 1 May 2006. [dead link]

- ^ "FDA Order Prohibits Extralabel Use Of Fluoroquinolones And Glycopeptides". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2 June 1997. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

External links

- Quinolone at Curlie

- Fact Sheet: Quinolones

- Information to healthcare professionals on fluoroquinolone safety from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration

- Fluoroquinolones "Family Practice Notebook" entry page for Fluoroquinolones

- Structure Activity Relationships "Antibacterial Agents; Structure Activity Relationships," André Bryskier MD