Porcelain

Porcelain (also known as China or Fine China) is a ceramic material made by heating materials, generally including clay in the form of kaolin, in a kiln to temperatures between 1,200 °C (2,192 °F) and 1,400 °C (2,552 °F). The toughness, strength, and translucence of porcelain arise mainly from the formation of glass and the mineral mullite within the fired body at these high temperatures.

Porcelain derives its present name from old Italian porcellana (cowrie shell) because of its resemblance to the translucent surface of the shell.[1] Porcelain can informally be referred to as "china" or "fine china" in some English-speaking countries, as China was the birthplace of porcelain making.[2] Properties associated with porcelain include low permeability and elasticity; considerable strength, hardness, toughness, whiteness, translucency and resonance; and a high resistance to chemical attack and thermal shock.

For the purposes of trade, the Combined Nomenclature of the European Communities defines porcelain as being "completely vitrified, hard, impermeable (even before glazing), white or artificially coloured, translucent (except when of considerable thickness), and resonant." However, the term porcelain lacks a universal definition and has "been applied in a very unsystematic fashion to substances of diverse kinds which have only certain surface-qualities in common" (Burton 1906).

Scope

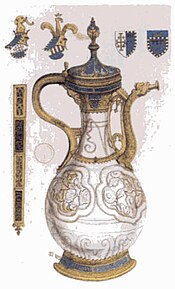

The most common uses of porcelain are for utilitarian wares and artistic objects. It can be difficult to distinguish between stoneware and porcelain because this depends upon how the terms are defined. A useful working definition of porcelain might include a broad range of ceramic wares, including some that could be classified as a stoneware. Porcelain is used to make household wares, decorative items and objects of fine art amongst other things.

Materials

Kaolin is the primary material from which porcelain is made, even though clay minerals might account for only a small proportion of the whole. The word "paste" is an old term for both the unfired and fired material. A more common terminology these days for the unfired material is "body", for example, when buying materials a potter might order an amount of porcelain body from a vendor.

The composition of porcelain is highly variable, but the clay mineral kaolinite is often a raw material. Other raw materials can include feldspar, ball clay, glass, bone ash, steatite, quartz, petuntse and alabaster.

The clays used are often described as being long or short, depending on their plasticity. Long clays are cohesive (sticky) and have high plasticity; short clays are less cohesive and have lower plasticity. In soil mechanics, plasticity is determined by measuring the increase in content of water required to change a clay from a solid state bordering on the plastic, to a plastic state bordering on the liquid, though the term is also used less formally to describe the facility with which a clay may be worked. Clays used for porcelain are generally of lower plasticity and are shorter than many other pottery clays. They wet very quickly, meaning that small changes in the content of water can produce large changes in workability. Thus, the range of water content within which these clays can be worked is very narrow and the loss or gain of water during storage and throwing or forming must be carefully controlled to keep the clay from becoming too wet or too dry to manipulate.

Methods

The following section provides background information on the methods used to form, decorate, finish, glaze, and fire ceramic wares.

Forming

Glazing

Unlike their lower-fired counterparts, porcelain wares do not need glazing to render them impermeable to liquids and for the most part are glazed for decorative purposes and to make them resistant to dirt and staining. Many types of glaze, such as the iron-containing glaze used on the celadon wares of Longquan, were designed specifically for their striking effects on porcelain.

Decoration

Porcelain wares may be decorated under the glaze using pigments that include cobalt and copper or over the glaze using coloured enamels. Like many earlier wares, modern porcelains are often biscuit-fired at around 1,000 degrees Celsius, coated with glaze and then sent for a second glaze-firing at a temperature of about 1,300 degrees Celsius or greater. Another early method is once-fired where the glaze is applied to the unfired body and the two fired together in a single operation.

Firing

In this process, green (unfired) ceramic wares are heated to high temperatures in a kiln to permanently set their shapes. Porcelain is fired at a higher temperature than earthenware so that the body can vitrify and become non-porous.

History

Chinese porcelain

Porcelain originated in China. Although proto-porcelain wares exist dating from the Shang Dynasty (1600–1046 BC), by the Eastern Han Dynasty period (196–220) glazed ceramic wares had developed into porcelain.[3][4] Porcelain manufactured during the Tang Dynasty (618–906) was exported to the Islamic world, where it was highly prized.[4][5] Early porcelain of this type includes the tri-colour glazed porcelain, or sancai wares. The exact dividing line between proto-porcelain and porcelain wares is not a clear one to date. Porcelain items in the sense that we know them today could be found in the Tang Dynasty,[6] and archaeological finds have pushed the dates back to as early as the Han Dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD).[3][7] By the Sui Dynasty (581–618) and Tang Dynasty (618–907), porcelain had become widely produced.

Eventually, porcelain and the expertise required to create it began to spread into other areas of East Asia. During the Song Dynasty (960–1279), artistry and production had reached new heights. The manufacture of porcelain became highly organised and the kiln sites, those excavated from this period, could fire as many as 25,000 wares.[7] By the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), porcelain art was being exported to Europe. Some of the most well-known Chinese porcelain art styles arrived in Europe during this era, such as the coveted blue-and-white wares.[8] The Ming Dynasty controlled much of the porcelain trade, which were further expanded to all over Asia, Africa and Europe through the Silk Road. Later, Portuguese merchants began direct trade over the sea route with the Ming Dynasty in 1517 and were followed by Dutch merchants in 1598.[5]

European porcelain

These exported Chinese porcelains were held in such great esteem in Europe that in the English language china became a commonly–used synonym for the Franco-Italian term porcelain. Apart from copying Chinese porcelain in faience (tin glazed earthenware), the soft-paste Medici porcelain in 16th-century Florence was the first real European attempt to reproduce it, with little success.

Early 16th century, the Portuguese brought back samples of kaolin clay, which they discovered in China to be essential in the production of porcelain wares, but the Chinese techniques and composition to manufacture porcelain were not yet fully understood.[7] Countless experiments to produce porcelain had unpredictable results and would meet with failure.[7] In the German state of Saxony, the search concluded with an eventual discovery in 1708 by Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus that produced a hard, white, translucent type of porcelain specimen with a combination of ingredients, including kaolin clay and alabaster, mined from a Saxon mine in Colditz.[9][10] It was closely guarded as a trade secret by the Saxon enterprise.[10][11]

In 1712, many of the elaborate Chinese manufacturing secrets for porcelain were revealed throughout Europe by the French Jesuit father Francois Xavier d'Entrecolles and soon published in the Lettres édifiantes et curieuses de Chine par des missionnaires jésuites.[12] The secrets of porcelain manufacturing, which d'Entrecolles read about and witnessed in China, were now known and began being used in Europe.[12]

Meissen

Von Tschirnhaus and Böttger were employed by Augustus the Strong and worked at Dresden and Meissen in the German state of Saxony. Tschirnhaus had a wide knowledge of European science and had been involved in the European quest to perfect porcelain manufacture when in 1705 Böttger was appointed to assist him in this task. Böttger had originally been trained as a pharmacist; after he turned to alchemical research, it was his claim that he knew the secret of transmuting dross into gold that attracted the attention of Augustus. Imprisoned by Augustus as an incentive to hasten his research, Böttger was obliged to work with other alchemists in the futile search for transmutation and was eventually assigned to assist Tschirnhaus.[9] One of the first results of the collaboration between the two was the development of a red stoneware that resembled the red stoneware of Yixing.

A workshop note records that the first specimen of hard, white and vitrified European porcelain was produced in 1708. At the time, the research was still being supervised by Tschirnhaus; however, he died in October of that year. It was left to Böttger to report to Augustus in March 1709 that he could make porcelain. For this reason, credit for the European discovery of porcelain is traditionally ascribed to him rather than Tschirnhaus.[13]

The Meissen factory was established in 1710 after the development of a kiln and a glaze suitable for use with Böttger's porcelain, which required firing at temperatures up to 1,400 °C (2,552 °F) to achieve translucence. Meissen porcelain was once-fired, or green-fired. It was noted for its great resistance to thermal shock; a visitor to the factory in Böttger's time reported having seen a white-hot teapot being removed from the kiln and dropped into cold water without damage. Evidence to support this widely disbelieved story was given in the 1980s when the procedure was repeated in an experiment at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.[citation needed]

Soft paste porcelain

The pastes produced by combining clay and powdered glass (frit) were called Frittenporzellan in Germany and frita in Spain. In France they were known as pâte tendre and in England as "soft-paste".[14] They appear to have been given this name because they do not easily retain their shape in the wet state, or because they tend to slump in the kiln under high temperature, or because the body and the glaze can be easily scratched.

Experiments at Rouen produced the earliest soft-paste in France, but the first important French soft-paste porcelain was made at the Saint-Cloud factory before 1702. Soft-paste factories were established with the Chantilly manufactory in 1730 and at Mennecy in 1750. The Vincennes porcelain factory was established in 1740, moving to larger premises at Sèvres[15] in 1756. Vincennes soft-paste was whiter and freer of imperfections than any of its French rivals, which put Vincennes/Sèvres porcelain in the leading position in France and throughout the whole of Europe in the second half of the 18th century.[16]

The first soft-paste in England was demonstrated by Thomas Briand to the Royal Society in 1742 and is believed to have been based on the Saint-Cloud formula. In 1749, Thomas Frye took out a patent on a porcelain containing bone ash. This was the first bone china, subsequently perfected by Josiah Spode.

In the twenty-five years after Briand's demonstration, half a dozen factories were founded in England to make soft-paste table-wares and figures:

- Chelsea (1743)[17][18]

- Bow (1745)[19][20][21]

- St James's (1748)[21][22]

- Bristol porcelain (1748)

- Longton Hall (1750)[23]

- Royal Crown Derby (1750 or 1757)[24][25]

- Royal Worcester (1751)

- Lowestoft porcelain (1757)[26][27]

- Wedgwood (1759)

- Spode (1767)

Other developments

William Cookworthy discovered deposits of kaolin clay in Cornwall, making a considerable contribution to the development of porcelain and other whiteware ceramics in the United Kingdom. Cookworthy's factory at Plymouth, established in 1768, used kaolin clay and china stone to make porcelain with a body composition similar to that of the Chinese porcelains of the early eighteenth century.

Types

Porcelain can be divided into the three main categories: hard-paste, soft-paste and bone china depending on the composition of the paste, the material used to form the body of a porcelain object and the firing conditions.

Hard paste

These porcelains that came from East Asia, especially China, were some of the finest quality porcelain wares. The earliest European porcelains were produced at the Meissen factory in the early 18th century; they were formed from a paste composed of kaolin and alabaster and fired at temperatures up to 1,400 °C (2,552 °F) in a wood-fired kiln, producing a porcelain of great hardness, translucency, and strength.[10] Later, the composition of the Meissen hard paste was changed and the alabaster was replaced by feldspar and quartz, allowing the pieces to be fired at lower temperatures. Kaolinite, feldspar and quartz (or other forms of silica) continue to provide the basic ingredients for most continental European hard-paste porcelains.

Soft paste

Soft-paste porcelains date back from the early attempts by European potters to replicate Chinese porcelain by using mixtures of clay and ground-up glass (frit) to produce soft-paste porcelain. Soapstone and lime were known to have been included in these compositions. These wares were not yet actual porcelain wares as they were not hard and vitrified by firing kaolin clay at high temperatures. As these early formulations suffered from high pyroplastic deformation, or slumping in the kiln at raised temperature, they were uneconomic to produce and of low quality. Formulations were later developed based on kaolin clay with quartz, feldspars, nepheline syenite or other feldspathic rocks. These were technically superior and continue in production. Soft-paste porcelains are fired at lower temperatures than hard-paste porcelain, therefore these are in general less hard than hard-paste porcelains.[28][29]

Bone china

Although originally developed in England since 1748[30] to compete with imported porcelain, bone china is now made worldwide. The English[clarification needed] had read the letters of Jesuit missionary Francois Xavier d'Entrecolles, which described Chinese porcelain manufacturing secrets in detail.[31] One writer has speculated that a misunderstanding of the text could possibly have been responsible for the first attempts to use bone-ash as an ingredient of English porcelain,[31] although this is not supported by researchers and historians.[32][33][34][35][36] In China, kaolin clay was sometimes described as forming the bones of the paste, while the flesh was provided by the refined rocks suitable for the porcelain body.[28][31] Traditionally English bone china was made from two parts of bone-ash, one part of kaolin clay and one part china stone, although this has largely been replaced by feldspars from non-UK sources.[37]

Other uses

Electric insulating material

Porcelain and other ceramic materials have many applications in engineering, especially ceramic engineering. Porcelain is an excellent insulator for use at high voltage, especially in outdoor applications. Examples are: terminals for high voltage cables, bushings of power transformers, insulation of high frequency antennas and many other components.

Building material

Porcelain can be used as a building material, usually in the form of tiles or large rectangular panels. Modern porcelain tiles are generally produced to a number of recognised international standards and definitions.[38][39] Manufacturers are found across the world[40] with Italy being the global leader, producing over 380 million square metres in 2006.[41] Historic examples of rooms decorated entirely in porcelain tiles can be found in several European palaces including ones at Capodimonte, Naples, the Royal Palace of Madrid and the nearby Royal Palace of Aranjuez.[42] and the Porcelain Tower of Nanjing in China. More recent noteworthy examples include The Dakin Building in Brisbane, California, and the Gulf Building in Houston, Texas, which when constructed in 1929 had a 70-foot-long (21 m) porcelain logo on its exterior.[43] A more detailed description of the history, manufacture and properties of porcelain tiles is given in the article “Porcelain Tile: The Revolution Is Only Beginning.”[43]

Manufacturers

- Europe

- Austria

- Czech Republic

- Haas & Czjzek, Horní Slavkov, (1792-2011)

- Thun 1794, Klášterec nad Ohří, (1794–present)

- Český porcelán a.s., Dubí, Eichwelder Porzellan und Ofenfabriken Bloch & Co. Böhmen, (1864–present)

- Rudolf Kämpf, Nové Sedlo (Sokolov District), (1907–present)

- Denmark

- Royal Copenhagen (1775–present)

- Finland

- Lithuania

- Poland

- Norway

- Romania

- Spain

- Switzerland

- Italy

- Richard-Ginori 1735 Manifattura di Doccia, (1735–2013)

- Hungary

- Herend Porcelain Manufacture, (1826–present)

- Hollóháza Porcelain Manufacture, (1777,1831–present)

- Zsolnay Porcelain Manufacture, (1853–present)

- Germany

- Portugal

- France

- Rouen porcelain, (1673–1696), faience

- Nevers porcelain, (1600–1789), faience

- Saint-Cloud porcelain, (1693–1766)

- Strasbourg faience, (1721-1784)

- Chantilly porcelain, (1730–1800)

- Vincennes porcelain, (1740–1756)

- Mennecy-Villeroy porcelain, (1745–1765)

- Sèvres porcelain, (1756–present)

- Revol porcelain, (1789–present)

- Haviland porcelain

- Japan

- Narumi

- Noritake

- Russia

- Dulevo Farfor (1832–present) Дулевский фарфор

- Imperial Porcelain Factory (1744), Oranienbaum

- Gzhel (ceramics) (1802), Gzhel (village)

- Turkey

- United Kingdom

- Aynsley China, (1775–present)

- Belleek, (1884-present)

- Chelsea porcelain factory

- Coalport porcelain

- Davenport

- Goss crested china

- Liverpool porcelain

- Mintons Ltd, (1793–1968, merged with Royal Doulton)

- New Hall porcelain

- Plymouth Porcelain

- Rockingham Pottery

- Royal Crown Derby, (1750/57-present)

- Royal Doulton, (1815-2009 acquired by KPS Capital Partners and part of WWRD Group Holdings Ltd)

- Royal Worcester, (1751-2008 acquired by Portmeirion Pottery)

- Spode, (1767-2008 acquired by Portmeirion Pottery)

- Wedgwood, (1759–2009 acquired by KPS Capital Partners and part of WWRD Group Holdings Ltd)

- United States

- Brazil

- Iran

- Vietnam

- Sri Lanka

- Dankotuwa Porcelain

- Noritake Lanka Porcelain

- United Arab Emirates

- RAK Porcelain

- South Korea

See also

References

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary: "The ceramic material was apparently so named on account of the resemblance of its translucent surface to the nacreous shell of the mollusc. [...] The cowrie was probably originally so named on account of the resemblance of the fissure of its shell to a vulva (it is unclear whether the reference is spec. to the vulva of a sow)."

- ^ OED, "China"; An Introduction to Pottery. 2nd edition. Rado P. Institute of Ceramic / Pergamon Press. 1988. Usage of "china" in this sense is inconsistent, & it may be used of other types of ceramics also.

- ^ a b Kelun, Chen (2004). Chinese porcelain: Art, elegance, and appreciation. San Francisco: Long River Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-59265-012-5.

- ^ a b "Porcelain". Columbia Encyclopedia Sixth Edition. 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- ^ a b Te-k'un, Cheng (1984). Studies in Chinese ceramics. Hong Kong: Chinese University Press. pp. 92–93. ISBN 978-962-201-308-7.

- ^ Adshead, S.A.M. (2004). T'ang China: The Rise of the East in World History. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1-4039-3456-8 (hardback). Page 80 & 83.

- ^ a b c d Temple, Robert K.G. (2007). The Genius of China: 3,000 Years of Science, Discovery, and Invention (3rd edition). London: André Deutsch, pp. 104-5. ISBN 978-0-233-00202-6

- ^ Cohen, David Harris (1993). Looking at European ceramics : a guide to technical terms. Malibu: The J. Paul Getty Museum Journal. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-89236-216-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Burns, William E. (2003). Science in the enlightenment: An encyclopedia. Santa Barbara: ABC-Clio. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-1-57607-886-0.

- ^ a b c Richards, Sarah (1999). Eighteenth-century ceramic: Products for a civilised society. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 23–26. ISBN 978-0-7190-4465-6.

- ^ Wardropper, Ian (1992). News from a radiant future: Soviet porcelain from the collection of Craig H. and Kay A. Tuber. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago. ISBN 978-0-86559-106-6.

- ^ a b • Baghdiantz McAbe, Ina (2008). Orientalism in Early Modern France. Oxford: Berg Publishing, p. 220. ISBN 978-1-84520-374-0

• Finley, Robert (2010). The pilgrim art. Cultures of porcelain in world history. University of California Press, p. 18. ISBN 978-0-520-24468-9

• Kerr, R. & Wood, N. (2004). Joseph Needham : Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 5 Chemistry and Chemical Technology : Part 12 Ceramic Technology. Cambridge University Press, p. 36-7. ISBN 0-521-83833-9

• Zhang, Xiping (2006). Following the steps of Matteo Ricci to China. Beijing: China Intercontinental Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-7-5085-0982-2.

• Burton, William (1906). Porcelain, Its Nature, Art and Manufacture. London. pp. 47–48.{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Gleeson, Janet. The Arcanum, an accurate historic novel on the greed, obsession, murder and betrayal that led to the creation of Meissen porcelain. Bantam Books, London, 1998.

- ^ Honey, W.B., European Ceramic Art, Faber and Faber, 1952, p.533

- ^ Munger, Jeffrey (October 2004). "Sèvres Porcelain in the Nineteenth Century". In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 31 October 2011

- ^ Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ^ ‘Science Of Early English Porcelain.’ I.C. Freestone. Sixth Conference and Exhibition of the European Ceramic Society. Vol.1 Brighton, 20–24 June 1999, p.11-17

- ^ ‘The Sites Of The Chelsea Porcelain Factory.’ E.Adams. Ceramics (1), 55, 1986.

- ^ "Bow". Museum of London. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ "Bow porcelain bowl, painted by Thomas Craft". British Museum. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ a b "Bow porcelain". British History Online. University of London & History of Parliament Trust. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ "St James's (Charles Gouyn)". Museum of London. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ Ceramic Figureheads. Pt. 3. William Littler And The Origins Of Porcelain In Staffordshire. Cookson Mon. Bull. Ceram. Ind. (550), 1986.

- ^ "History". Royal Crown Derby. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ^ History of Royal Crown Derby Co Ltd, from "British Potters and Potteries Today", publ 1956

- ^ 'The Lowestoft Porcelain Factory, and the Chinese Porcelain Made for the European Market during the Eighteenth Century.' L. Solon. The Burlington Magazine. No. 6. Vol.II. August 1906.

- ^ Norfolk Museums & Archaeology Service[dead link]

- ^ a b Reed, Cleota (1997). Syracuse China. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-0-8156-0474-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ N. Hudson Moore (1903). The Old China Book. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-4344-7727-9.

- ^ Strumpf, Faye (2000). Limoges boxes: A complete guide. Iola, WI: Krause Publications. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-87341-837-9.

- ^ a b c Burton, William. Porcelain, Its Nature, Art and Manufacture. London. pp. 18–19.

- ^ Science Of Early English Porcelain. Freestone I C. Sixth Conference and Exhibition of the European Ceramic Society. Extended Abstracts. Vol.1 Brighton, 20–24 June 1999, pg.11-17

- ^ The Special Appeal Of Bone China. Cubbon R C P.Tableware Int. 11, (9), 30, 1981

- ^ All About Bone China. Cubbon R C P. Tableware Int. 10, (9), 34, 1980

- ^ Spode's Bone China - Progress In Processing Without Compromise In Quality. George R T; Forbes D; Plant P. Ceram. Ind. 115, (6), 32, 1980

- ^ An Introduction To The Technology Of Pottery. Paul Rado. Institute of Ceramics & Pergamon Press, 1988

- ^ Changes & Developments Of Non-plastic Raw Materials. Sugden A. International Ceramics Issue 2 2001.

- ^ “New American Standard Defines Polished Porcelain By The Porcelain Tile Certification Agency.” Tile Today No.56, 2007.

- ^ Porcelain tile as defined in ASTM C242 - 01(2007) Standard Terminology of Ceramic Whitewares and Related Products published by ASTM International.

- ^ ’Manufacturers Of Porcelain Tiles’ Ceram.World Rev. 6, No.19, 1996 … ‘The main manufacturers of porcelain tiles in Italy, Europe, Asia, Africa, Oceania and the Americas are listed.’

- ^ ”Italian Porcelain Tile Production At The Top” Ind.Ceram. 27, No.2, 2007.

- ^ Porcelain Room, Aranjuez Comprehensive but shaky video

- ^ a b “Porcelain Tile: The Revolution Is Only Beginning.” Tile Decorative Surf. 42, No.11, 1992.

Further reading

- Combined Nomenclature of the European Communities - EC Commission in Luxembourg, 1987 .

- Burton, William (1906). Porcelain, its Nature, Art and Manufacture. Batsford, London

- Valenstein, S. (1998). A handbook of Chinese ceramics, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. ISBN 9780870995149