Racism in China

Ethnic issues in China are complex and arise from the influences of Chinese history, Chinese nationalism, and many other factors. Ethnic issues have driven multiple Chinese historical movements, including Red Turban Rebellion — which targeted Mongol leaderships of the Yuan Dynasty — as well as in the Xinhai Revolution which overthrew the Manchus, Qing Dynasty. An ethnic dynamic is sometimes seen in modern unrest, such as the July 2009 Ürümqi riots.

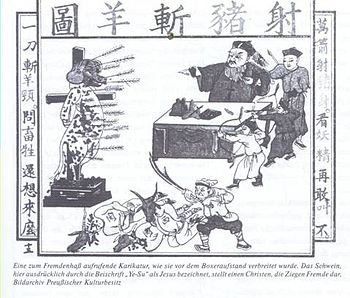

Racism and ethnic tensions in pre-modern China

Pejorative statements about non-Han Chinese can be found in some ancient Chinese texts. For example, a 7th century commentary to the Hanshu by Yan Shigu on the Wusun people likens "barbarians who have green eyes and red hair" to macaque monkeys.[1]

Some conflicts between different races and ethnicities resulted in genocide. Ran Min, a Han chinese leader, during the Wei–Jie war, massacred non-Chinese Wu Hu peoples around 350 A.D. in retaliation for abuses against the Chinese population, with the Jie people particularly affected.[2]

Rebels slaughtered many Arabs and Persian merchants in the Yangzhou massacre (760). The Arab historian Abu Zayd Hasan of Siraf reports when the rebel Huang Chao captured Guang Prefecture, his army killed a large number of foreign merchants resident there: Muslims, Jews, Christians, and Parsees, in the Guangzhou massacre.[3]

In the 20th century, the social and cultural critic Lu Xun commented that, "throughout the ages, Chinese have had only two ways of looking at foreigners, up to them as superior beings or down on them as wild animals." [4]

Racism and ethnic prejudice among minorities

The Mongols divided different races into a four-class caste system during the Yuan dynasty.

The Mongol Emperor Kublai Khan had introduced a hierarchy of reliability by dividing the population of the Yuan Dynasty into the following classes:

- Mongols

- Semuren, immigrants from the west and some clans of Central Asia (Muslims, Christians, Jews, Buddhists)

- North Chinese, Kitans, Jurchens and Koreans

- Southerners, or all subjects of the former Song Dynasty

Partner merchants and non-Mongol overseers were usually either immigrants or local ethnic groups. Thus, in China they were Turkestani and Persian Muslims, and Christians. Foreigners from outside the Mongol Empire entirely, such as the Polo family, were welcomed everywhere.

Despite the high position given to Muslims, the Yuan Mongols discriminated against them severely, restricting Halal slaughter and other Islamic practices like Circumcision, as well as Kosher butchering for Jews, forcing them to eat food the Mongol way. Genghis Khan directly called Muslims "slaves".[5][6] Toward the end, corruption and persecution became so severe that Muslim Generals joined the Han chinese in rebelling against the Mongols. The Ming founder Zhu Yuanzhang had Muslim Generals including Lan Yu who rebelled against the Mongols and defeated them in combat. Some Muslim communities had the name which in chinese means "baracks" or "thanks". Many Hui Muslims claim it is because they played an important role in overthrowing the Mongols and in thanks by the Han chinese.[7] The Muslims in the semu class also revolted against the Yuan dynasty in the Ispah Rebellion but the rebellion was crushed and the Muslims were massacred by the Yuan loyalist commander Chen Youding.

Uyghurs have also exhibited racism as well. The Uyghur leader Sabit Damulla Abdulbaki made the following proclamation on Han chinese and Tungans (Hui Muslims):

"The Tungans, more than the Han, are the enemy of our people. Today our people are already free from the oppression of the Han, but still continue under Tungan subjugation. We must still fear the Han, but cannot fear the Tungans also. The reason we must be careful to guard against the Tungans, we must intensely oppose, cannot afford to be polite. Since the Tungans have compelled us, we must be this way. Yellow Han people have not the slightest thing to do with Eastern Turkestan. Black Tungans also do not have this connection. Eastern Turkestan belongs to the people of Eastern Turkestan. There is no need for foreigners to come be our fathers and mothers...From now on we do not need to use foreigners language, or their names, their customs, habits, attitudes, written language, etc. We must also overthrow and drive foreigners from our boundaries forever. The colors yellow and black are foul. They have dirtied our land for too long. So now it is absolutely necessary to clean out this filth. Take down the yellow and black barbarians! Long live Eastern Turkestan!"[8][9]

American telegrams reported that certain Uyghur mobs in parts of Xinjiang were calling for White Russians to be expelled from Xinjiang during the Ili Rebellion, along with Han Chinese. They were reported to say, "We freed ourselves from the yellow men, now we must destroy the white". The telegram also reported that "Serious native attacks on people of other races frequent. White Russians in terror of uprising."[10]

During the late 19th century around Qinghai tensions exploded between different Muslim sects, between different ethnic groups, with emminty and division rising between Hui Muslims and Salar Muslims, and all tensions rising between Muslims, Tibetans and Han.[11]

The "Encyclopædia of religion and ethics, Volume 8" stated that the Dungan and Panthay revolts by the Muslims was set off by racial antagonism and class warfare, rather than the mistaken assumption that it was all due to Islam and religion that the rebellions broke out.[12]

Racial and ethnic segregation

Several laws enforcing racial segregation of foreigners were passed during the Tang Dynasty. In 779 AD, Tang dynasty issued an edict which forced Uighurs to wear their ethnic dress, and restricted them from marrying Chinese. Chinese disliked Uighurs because they practiced usury.[citation needed]

In 836 AD Lu Chun was appointed as governor of Canton, he was disgusted to find Chinese living with foreigners and intermarriage. Lu enforced separation, banning interracial marriages, and restricting foreigners to own properties.[13] The 836 law specifically banned Chinese from forming relationships with "Dark peoples" or "People of colour", terms referring to foreigners, such as "Iranians, Sogdians, Arabs, Indians, Malays, Sumatrans", etc.[14][15]

Racial and ethnic composition

China's ethnic composition is largely homogeneous with 91.9% of the population being Han Chinese, other ethnicities are Mongols, Zhuang, Miao, Hui, Tibetans, Uyghurs and Koreans.[16]

Some ethnic groups are more distinguishable due to physical appearances and relatively low intermarriage rates. Many others have intermarried with Han Chinese, and have similar appearances. They are therefore less distinguishable from Han Chinese people, especially because a growing number of ethnic minorities are fluent at a native level in Mandarin Chinese. In addition, children often adopts "ethnic minority status" at birth if one of their parents is an ethnic minority, even though their ancestry is overwhelmingly Han Chinese. There is a growing number of Europeans, South Asians, and Africans living in large Chinese cities. Although relatively few acquire Chinese citizenship, the number of immigrants belonging to different racial groups has markedly increased recently due to China's economic success[citation needed]. There are concentrated pockets of immigrants and foreign residents in some cities.

In May 2012, a 100-day crackdown on illegal foreigners in Beijing began, with many Beijing locals wary of foreign nationals as a result of recent crime events.[17][18] China Central Television host Yang Rui made a controversial statement that "foreign trash" should be cleaned out of Beijing.[17]

Anti-Japanese sentiment

Anti-Japanese sentiment exists in China, most of it stemming from Japanese war crimes committed in the country during the Second Sino-Japanese War. History textbook revisionism in Japan and the denial or whitewashing of events such as the Nanking Massacre by right-wing Japanese groups has continued to inflame anti-Japanese feelings in China. It has been alleged that anti-Japanese sentiment in China is partially the result of political manipulation by the Communist Party of China.[19] According to a BBC report, anti-Japanese demonstrations are said to have received tacit approval from Chinese authorities, although the Chinese ambassador to Japan, Wang Yi, stated that the Chinese government does not condone such protests.[20]

Tensions with Uyghurs

A Uyghur proverb says "Protect religion, Kill the Han and destroy the Hui".(baohu zongjiao, sha Han mie Hui 保護宗教,殺漢滅回).[21][22]

Anti Hui poetry was written by Uyghurs.[23]

In Bayanday there is a brick factory,

it had been built by the Chinese.

If the Chinese are killed by soldiers,

the Tungans take over the plundering.

It was also alleged that a Uyghur would not enter the mosque of Hui people, and Hui and Han households were built closer together in the same area while Uyghurs would live farther away from the town.[23]

Sometimes Uyghurs regard Hui Muslims from other provinces of China as fakes and refuse to eat food prepared by them.[24] Uyghurs view food prepared by Hui as unpure and will not buy meat from Hui, and protests by Uyghur teachers in 1989 at Turpan erupted because Uyghurs refused to eat food prepared by Hui.[25]

Children who are of mixed Han and Uyghur ethnicities are known as erzhuanzi (二转子) and Uyghurs call them piryotki.[25][26] They are shunned by Uyghurs at social gatherings and events.[27]

Some have accused the Chinese government as well as certain Han Chinese citizens of alleged discrimination against the Turkic Muslim Uyghur minority.[28][29] This was used as a partial explanation for the July 2009 Ürümqi riots which pitted residents of the city against each other along largely racial lines. An essay in the People's Daily described the events as "so-called racial conflict"[30] while several Western media sources labeled them as "race riots".[31][32][33]

It has also been reported that unofficial Chinese policy is to deny passports to Uyghurs until they reach retirement age, especially if they intend to leave the country for the pilgrimage to Mecca.[28]

Tensions between Hui and Uyghurs arose because Qing and Republican Chinese authorities used Hui troops and officials to dominate the Uyghurs and crush Uyghur revolts.[34]

Hui population of Xinjiang increased by 520 percent from 1940–1982, average annual growth of 4.4 percent, the Uyghur population grew at 1.7 percent. This increase in Hui population led to tensions between the Hui Muslim and Uyghur Muslim populations. Some old Uyghurs in Kashgar remember that the Hui army at the Battle of Kashgar (1934) massacred 2,000 to 8,000 Uyghurs, which caused tension as more Hui moved into Kashgar from other parts of China.[35]

Tibetan racism and ethnic prejudice

In the frontier districts of Sichuan, and other ethnic Tibetan areas in China, many people are of mixed Han-Tibetan ethnicity. These half-Han, half-Tibetans were despised by pure Tibetans.[36]

Ethnic Tibetan Muslims (called Kache in Tibetan) have lived peacefully alongside Tibetan Buddhists for over a thousand years, because Buddhist Tibetans are prohibited by their religion from killing animals, yet require meat to survive in their mountain climate. However, Tibetans have severe problems with Chinese Muslims (called Kyangsha in Tibetan).[37]

In history, Tibetans and Mongols refused to allow other ethnic groups such as Kazakhs to participate in the Kokonur ceremony in Qinghai, until the Muslim General Ma Bufang urged to stop the practice.[38]

Other racism and ethnic prejudice

Hatred of foreigners from high ranking Chinese Muslim officers stemmed from the arrogant way foreigners handled Chinese affairs, rather than for religious reasons, the same reason other non Muslim Chinese hated foreigners. Promotion and wealth were other motives among Chinese Muslim military officers for anti foreignism.[39]

A Hui soldier of the 36th division called Sven Hedin a "foreign devil", which is a now antiquated Chinese slur referring to foreigners.[40][41]

The Tungans (Chinese Muslims) were reported to be "strongly anti-Japanese".[42]

In the 1930s, a White Russian driver accompanying the Nazi agent Georg Vasel in Xinjiang was afraid to meet the Hui General Ma Zhongying, saying "You know how the Tungans hate the Russians." Tungan is another name for Chinese Muslim. Georg passed the Russian driver off as German to get through.[43]

One of the Chinese Muslim generals encountered by Peter Fleming was concerned that his visitor was a foreign "barbarian" and was only impressed when he found out his outlook was Chinese in nature.[44] The racist atmosphere made a Uighur feel inclined to grovel at the General's feet when asking for help. Other Uighur notables were forced to pay respect to the General, while his soldiers showed contempt.[45][46] Racial slurs were allegedly used by the Chinese Muslim troops against Uighurs.[47]

Hui General Ma Qi launched a racial war against the Tibetan Ngoloks, in 1928, inflicting a defeat upon them and seizing the Labrang Buddhist monastery.[citation needed] The Hui had a feud against the Ngoloks for a long time.[citation needed] Ma Qi's Muslim forces also machine-gunned Tibetan monks and ravaged the monastery several times, leaving thousands dead in bloody battles.[48][49]

In 1936, after Sheng Shicai expelled 20,000 Kazakhs from Xinjiang to Qinghai, Hui led by General Ma Bufang massacred their fellow Muslim Kazakhs, until there were 135 of them left.[50][51]

The Empress Dowager Cixi was known for her xenophobia against non-Chinese peoples despite being a non-Han Chinese herself, also using the term foreign devils to describe them. Lao She, a Manchu writer, also called Europeans foreign devils.

Ethnic slurs

Against Europeans and Westerners

- 洋鬼子 (yáng guǐzi) - "Western devil", a derogatory term for white people or Caucasians popularized during the First Opium War, when the British empire waged and won a war so that their merchants could legally sell opium. This term is no longer widely used.

- 鬼佬 (guǐlǎo) - Borrowed from Cantonese "Gweilo", literally "ghost guy", a slur for White people.

- 红毛 (ang mo) - "Red Hair" or "Red Fur", a slur used by Hokkien (Min-nan) people in Taiwan and Singapore to primarily refer to Dutch colonists who settled in Taiwan and British colonists who settled in Singapore during the 17th century and early 19th century respectively.

- 毛子 (máo zi) - literally “body hair”, it is a derogatory term for Caucasian peoples. However, because most white people in contact with China were Russians before the 19th century, 毛子 became a derogatory term that refers specifically to Russians.[52][53]

The historian Frank Dikötter explains.

A common historical response to serious threats directed towards a symbolic universe is 'nihilation', or the conceptual liquidation of everything inconsistent with official doctrine. Foreigners were labelled 'barbarians' or 'devils' to be conceptually eliminated. The official rhetoric reduced the Westerner to a devil, a ghost, an evil and unreal goblin hovering on the border of humanity. Many texts of the first half of the nineteenth century referred to the English as 'foreign devils' (yangguizi), 'devil slaves' (guinu), 'barbarian devils' (fangui), 'island barbarians' (daoyi), 'blue-eyed barbarian slaves' (biyan yinu), or 'red-haired barbarians' (hongmaofan).[54]

Against indigenous peoples

- 番鬼 (Fan Guai) - a slur that is used by some Southern Chinese from the Guangdong area to refer to foreigners, where 番 (Fan) means "Tribal people". In the past, The Minnan and Chaozhou people used 山番 (mountain tribal people) and 生番 (raw tribal people) to describe the natives and aboriginals of Taiwan.

Against Japanese

- 小日本 (xiǎo Rìběn) — Literally "little Japan"(ese). This term is so common that it has very little impact left (Google Search returns 21,000,000 results as of August 2007). The term can be used to refer to either Japan or individual Japanese. "小", or the word "little", is usually construed as "puny", "lowly" or "small country", but not "spunky".

- 日本鬼子 (Rìběn guǐzi) — Literally "Japanese devil". This is used mostly in the context of the Second Sino-Japanese War, when Japan invaded and occupied large areas of China. This is the title of a Japanese documentary on Japanese war crimes during WWII.

- 倭 (Wō) — An ancient Chinese name for Japan, but it was also adopted by the Japanese, pronounced Wa. In current Chinese usage, Wō is usually intended to give a negative connotation (see Wōkòu below). Two commonly proposed etymologies for this word are "submissive; obedient" or "dwarf; short person".[55] In the 7th century, Japanese scribes replaced 倭 (Wō/Wa) with 和 (Hé/Wa) meaning "harmony."

- 倭寇 (Wōkòu) — Originally referred to Japanese pirates and armed sea merchants who raided the Chinese coastline during the Ming Dynasty (see Wokou). The term was adopted during the Second Sino-Japanese War to refer to invading Japanese forces, (similarly to Germans being called Huns).

- 自慰队 (zì wèi duì) - A pun on the homophone "自卫队" (zì wèi duì, literally "Self-Defence Forces", see Japan Self-Defense Forces), the definition of 慰 (wèi) used is "to comfort". This phrase is used to refer to Japanese (whose military force is known as "自卫队") being stereotypically hypersexual, as "自慰队" means "Self-comforting Forces", referring to masturbation.

- 架佬 (Ga Lou)-A neutral term for Japanese used by Cantonese (especially Hong Kong Cantonese), because Japanese use a lot of "Ga" at the end of a sentence. 架妹 (Ga Mui) is used for female Japanese.

- 蘿蔔頭 (Lo Baat Tau) — Literally meaning "Radish Head," used by the Cantonese to refer to the Japanese during World War II. This term was a reference to the popular Japanese hair style at the time which was regarded as making their heads look like a white radish.

Against Koreans

- 高丽棒子 (Gāolì bàng zǐ) - Derogatory term used against all ethnic Koreans. 高丽 (Traditional: 高麗) refers to Ancient Korea (Koryo), while 棒子 means "club" or "corncob", referring to the weapon used by the puppet Korean police during the Anti-Japanese War of China.

- 二鬼子 (èr guǐ zǐ)[56] - A disparaging designation of puppet armies and traitors during the Anti-Japanese War of China.[57][58] Japanese were known as "鬼子" (devil), and the 二鬼子 literally means "second devils". During World War II, some Koreans were involved in Imperial Japanese Army, and so 二鬼子 refers to hanjian and ethnic Koreans. The definition of 二鬼子 has changed throughout time[original research?], with modern slang usage entirely different from its original meaning during World War II and the subsequent Chinese civil war.[citation needed]

Against Africans and Blacks

- 黑鬼 (hei guǐ) - "Black devil"[59]

Against Indians

- 阿差 (Ah Cha)-Ah Cha means "Good" in some Indian languages, is a derogatory Cantonese term used against Indians. During the 1950s-1970s, there were many Indians working in Hong Kong as laborers, or doormen, especially doormen for hotels.[citation needed]

- 阿三 (A Sae) or 红头阿三 (Ghondeu Asae) - Originally a Shanghainese term used against South Asians. This term is now used in Mandarin as well.[60]

Against Uyghurs

- Ch'an-t'ou (纏頭; turban heads) (used during the Republican period)[47][61]

- nao-tzu-chien-tan (脑子简单; simple-minded) (used during the Republican period)[47]

Against mixed races

- erzhuanzi (二转子) children who are mixed Uyghur and Han.[25][26] This term "Erh-hun-tze", was said by European explorers in the 19th century to refer to a people who were descended from a mixture of Chinese, Taghliks, and Mongols living in the area from Ku-ch'eng-tze to Barköl in Xinjiang.[62]

Orthographic pejoratives

Some Chinese characters used to transcribe non-Chinese peoples were graphically pejorative ethnic slurs, where the insult derived not from the Chinese word but from the character used to write it. Take for instance, the Written Chinese transcription of Yao "the Yao people", who primarily live in the mountains of southwest China and Vietnam. When 11th-century Song Dynasty authors first transcribed the exonym Yao, they insultingly chose yao 猺 "jackal" from a lexical selection of over 100 characters pronounced yao (e.g., 腰 "waist", 遙 "distant", 搖 "shake"). During a series of 20th-century Chinese language reforms, this graphic pejorative 猺 (written with the 犭"dog/beast radical") "jackal; the Yao" was replaced twice; first with the invented character yao 傜 (亻"human radical") "the Yao", then with yao 瑤 (玉 "jade radical") "precious jade; the Yao." Chinese orthography (symbols used to write a language) can provide unique opportunities to write ethnic insults logographically that do not exist alphabetically. For the Yao ethnic group, there is a difference between the transcriptions Yao 猺 "jackal" and Yao 瑤 "jade" but none between the romanizations Yao and Yau.

See also

References

- ^ Book of Han, with commentary by Yan Shigu Original text: 烏孫於西域諸戎其形最異。今之胡人青眼、赤須,狀類彌猴者,本其種也。

- ^ Mark Edward Lewis (2009). China between empires: the northern and southern dynasties. Harvard University Press. p. 76. ISBN 0-674-02605-5. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Gabriel Ferrand, ed. (1922). Voyage du marchand arabe Sulaymân en Inde et en Chine, rédigé en 851, suivi de remarques par Abû Zayd Hasan (vers 916). p. 76.

- ^ Simon Leys, Chinese Shadows (New York: The Viking Press, 1977), 1. Leys has noted that Lu Xun's polemical utterance can be applied to the Maoist bureaucracy at the time Leys wrote his book. However, Leys also pointed out that it would be unfair to apply Lu Xun's statement to the Chinese people in general. As according to Leys, the Chinese people themselves are friendly and hospitable to foreigners.

- ^ Michael Dillon (1999). China's Muslim Hui community: migration, settlement and sects. Richmond: Curzon Press. p. 24. ISBN 0-7007-1026-4. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Johan Elverskog (2010). Buddhism and Islam on the Silk Road. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 340. ISBN 0-8122-4237-8. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Dru C. Gladney (1996). Muslim Chinese: ethnic nationalism in the People's Republic. Cambridge Massachusetts: Harvard Univ Asia Center. p. 234. ISBN 0-674-59497-5. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Zhang, Xinjiang Fengbao Qishinian [Xinjiang in Tumult for Seventy Years], 3393-4.

- ^ The Islamic Republic of Eastern Turkestan and the Formation of Modern Uyghur Identity in Xinjiang, by JOY R. LEE [1]

- ^ UNSUCCESSFUL ATTEMPTS TO RESEOLVE POLITICAL PROBLEMS IN SINKIANG; EXTENT OF SOVIET AID AND ENCOURAGEMENT TO REBEL GROUPS IN SINKIANG; BORDER INCIDENT AT PEITASHAN

- ^ Paul Kocot Nietupski (1999). Labrang: a Tibetan Buddhist monastery at the crossroads of four civilizations. Snow Lion Publications. p. 82. ISBN 1-55939-090-5. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ^ James Hastings, John Alexander Selbie, Louis Herbert Gray (1916). Encyclopædia of religion and ethics, Volume 8. T. & T. Clark. p. 893. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Edward H. Schafer (1963). The golden peaches of Samarkand: a study of Tʻang exotics. University of California Press. p. 22. ISBN 0-520-05462-8. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Mark Edward Lewis (2009). China's cosmopolitan empire: the Tang dynasty. Harvard University Press. p. 170. ISBN 0-674-03306-X. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ^ Jacques Gernet (1996). A history of Chinese civilization. Cambridge University Press. p. 294. ISBN 0-521-49781-7. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ^ "China". CIA. Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- ^ a b Jemimah Steinfeld, 25 May 2012, Mood darkens in Beijing amid crackdown on 'illegal foreigners', CNN

- ^ 15 May 2012, Beijing Pledges to ‘Clean Out’ Illegal Foreigners, China Real Time Report, Wall Street Journal

- ^ Shirk, Susan (2007-04-05). "China: Fragile Superpower: How China's Internal Politics Could Derail its Peaceful Rise". Retrieved 2007-07-29.

- ^ "China's anti-Japan rallies spread". BBC News. 2005-04-10.

- ^ .The Islamic Republic of Eastern Turkestan and the Formation of Modern Uyghur Identity in Xinjiang, by JOY R. LEE [2]

- ^ Robyn R. Iredale, Naran Bilik, Fei Guo (2003). China's minorities on the move: selected case studies. M.E. Sharpe. p. 170. ISBN 0-7656-1023-X. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Ildikó Bellér-Hann (2008). Community matters in Xinjiang, 1880-1949: towards a historical anthropology of the Uyghur. BRILL. p. 75. ISBN 90-04-16675-0. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Yangbin Chen (2008). Muslim Uyghur students in a Chinese boarding school: social recapitalization as a response to ethnic integration. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 130. ISBN 0-7391-2112-X. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

- ^ a b c David Westerlund, Ingvar Svanberg (1999). Islam outside the Arab world. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 204. ISBN 0-312-22691-8. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

- ^ a b Ildikó Bellér-Hann (2007). Situating the Uyghurs between China and Central Asia. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 223. ISBN 0-7546-7041-4. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

- ^ Justin Ben-Adam Rudelson, Justin Jon Rudelson (1997). Oasis identities: Uyghur nationalism along China's Silk Road. Columbia University Press. p. 86. ISBN 0-231-10786-2. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

- ^ a b "No Uighurs Need Apply". The Atlantic. 10 Jul 2009. Retrieved 12 July 2009.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Uighurs blame 'ethnic hatred'". Al Jazeera. July 7, 2009. Retrieved 12 July 2009.

- ^ Global Times (10 July 2009). "People's Daily criticizes double standards in Western media attitudes to 7.5 incident". China News Wrap. original article in Chinese

- ^ "Race Riots Continue in China's Far West". Time magazine. 2009-07-07. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Deadly race riots put spotlight on China". The San Francisco Chronicle. July 8, 2009. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Three killed in race riots in western China". The Irish Times. July 6, 2009. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ S. Frederick Starr (2004). Xinjiang: China's Muslim borderland. M.E. Sharpe. p. 311. ISBN 0-7656-1318-2. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ S. Frederick Starr (2004). Xinjiang: China's Muslim borderland. M.E. Sharpe. p. 113. ISBN 0-7656-1318-2. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Friedrich Ratzel (1898). The history of mankind, Volume 3. Macmillan and co., ltd. p. 355. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

- ^ Shail Mayaram (2009). The other global city. Taylor & Francis US. p. 76. ISBN 0-415-99194-3. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

- ^ Uradyn Erden Bulag (2002). Dilemmas The Mongols at China's edge: history and the politics of national unity. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 54. ISBN 0-7425-1144-8. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ James Hastings, John Alexander Selbie, Louis Herbert Gray (1916). Encyclopædia of religion and ethics, Volume 8. T. & T. Clark. p. 893. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ History of the expedition in Asia, 1927-1935, Part 3. Göteborg, Elanders boktryckeri aktiebolag. 1945. p. 78. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

{{cite book}}:|first=missing|last=(help); Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Francis Hamilton Lyon, Sven Hedin (1936). The flight of "Big Horse": the trail of war in Central Asia. E. P. Dutton and co., inc. p. 92. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Andrew D. W. Forbes (1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: a political history of Republican Sinkiang 1911-1949. Cambridge, England: CUP Archive. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-521-25514-1. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Georg Vasel, Gerald Griffin (1937). My Russian jailers in China. Hurst & Blackett. p. 143. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Peter Fleming (1999). News from Tartary: A Journey from Peking to Kashmir. Evanston Illinois: Northwestern University Press. p. 308. ISBN 0-8101-6071-4. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Peter Fleming (1999). News from Tartary: A Journey from Peking to Kashmir. Evanston Illinois: Northwestern University Press. p. 308. ISBN 0-8101-6071-4. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Christian Tyler (2004). Wild West China: the taming of Xinjiang. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. p. 265. ISBN 0-8135-3533-6. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ a b c Andrew D. W. Forbes (1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: a political history of Republican Sinkiang 1911-1949. Cambridge, England: CUP Archive. p. 307. ISBN 0-521-25514-7. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ James Tyson, Ann Tyson (1995). Chinese awakenings: life stories from the unofficial China. Westview Press. p. 123. ISBN 0-8133-2473-4. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Paul Kocot Nietupski (1999). Labrang: a Tibetan Buddhist monastery at the crossroads of four civilizations. Snow Lion Publications. p. 90. ISBN 1-55939-090-5. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ American Academy of Political and Social Science (1951). The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Volume 277. American Academy of Political and Social Science. p. 152. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ American Academy of Political and Social Science (1951). Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Volumes 276-278. American Academy of Political and Social Science. p. 152. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ 2012-05-02, 中俄军演刚结束:毛子这举动让北京狼狈不堪! (China-Russia military exercises conclude, the actions of Mao zi force Beijing into a dilemma), 环球视线

- ^ 2012-08-26, 毛子告诉中国:美国佬不敢惹俄罗斯只是因为这 (Mao zi tell China: Yankees won't mess with Russia because of this), 参考啊

- ^ Dikötter, Frank (1992). The Discourse of Race in Modern China. Stanford University Press, p. 36.

- ^ Carr, Michael (1992). "Wa 倭 Wa 和 Lexicography." International Journal of Lexicography 5.1, p. 9.

- ^ 第一滴血──從日方史料還原平型關之戰日軍損失 (6) News of the Communist Party of China December 16, 2011

- ^ Comprehensive Chinese-English Dictionary

- ^ mdbg Chinese English Dictionary

- ^ Hooi, Alexis (2009-07-31). "The disunited colors of prejudice". China Daily. Retrieved 2009-11-24.

Even now, some Guangzhou residents might admit using the generic and derogatory term "hei gui" or "ghost" to refer to Africans in the community.

- ^ "上海滩的"红头阿三"". Retrieved 2010-08-01.

- ^ Garnaut, Anthony. "From Yunnan to Xinjiang:Governor Yang Zengxin and his Dungan Generals" (PDF). Pacific and Asian History, Australian National University). Retrieved 2010-07-14.

- ^ Roerich Museum, George Roerich (2003). Journal Of Urusvati Himalayan Research Institute, Volumes 1-3. Vedams eBooks (P) Ltd. p. 526. ISBN 81-7936-011-3. Retrieved 2010-06-28.