Huang Chao

It has been suggested that this article be split into a new article titled Huang Chao Rebellion. (discuss) (February 2023) |

| Huang Chao | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Emperor of the Kingdom of Qi | |||||||||

| Reign | January 16, 881[1][2] – July 13, 884 | ||||||||

| Born | 835 | ||||||||

| Died | July 13, 884 (48–49) [1][3] | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Dynasty | Kingdom of Qi (齊)[2] | ||||||||

| Huang Chao | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 黃巢 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 黄巢 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Emperor Huang Chao (835 – July 13, 884) was a wealthy Han Chinese salt trader, soldier, rebel and is most well known for being the first and only Emperor of his own country of the Kingdom of Qi (齊國) that fought against the Tang dynasty military and severely weakened and almost defeated the Tang dynasty had Emperor Huang Chao not been betrayed and assassinated by one of his own trusted nephews who had been bribed with money and positions of power by the Tang Dynasty government.

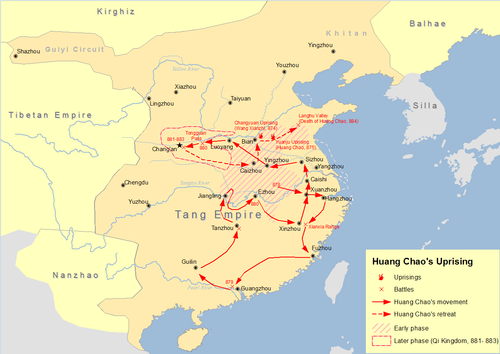

Emperor Huang had worked many years as a salt trader before joining Wang Xianzhi's rebellion against the Tang Dynasty in the mid-870s. After splitting with Wang, his army turned south and conquered Guangzhou. In 881, his troops captured the Tang Dynasty capital Chang'an, forcing Emperor Xizong of Tang to flee. Huang proclaimed himself the Emperor of the Kingdom of Qi (齊國) and reigned on the imperial dragon throne for almost four years but was eventually defeated in battle by the rival Tang dynasty army led by the Shatuo chieftain Li Keyong in 883 and forced to desert and escape Chang'an. Following successive defeats, including to former subordinates Zhu Wen and Shang Rang who had surrendered to Tang, Huang was allegedly killed by his nephew Lin Yan, although the reports are inconclusive. Some other sources state that Huang had escaped to safety with his family, servants, bodyguards and his royal staff.

Background

[edit]The Tang dynasty, established in 618 A.D., had already passed its golden age and entered its long decline beginning with the An Lushan Rebellion by general An Lushan. The Tang dynasty recovered its power decades after the An Lushan rebellion and was still able to launch offensive conquests and campaigns like its destruction of the Uyghur Khaganate in Mongolia in 840–847. It was the Huang Chao rebellion in 874–884 by the native Han rebel Huang Chao that permanently destroyed the power of the Tang dynasty. The power of the jiedushi or provincial military governors increased greatly after imperial troops crushed the rebels. The discipline of these generals also decayed as their power increased, the resentment of common people against the incapacity of the government grew, and their grievances exploded into several rebellions during the mid-9th century. Many impoverished farmers, tax-burdened landowners and merchants, as well as many large salt smuggling operations, formed the base of the anti-government rebellions of this period. Wang Xianzhi and Huang Chao were two of the important rebel leaders during this era.[4]

It is not known when Huang was born, but it is known that he was from Yuanqu (within the present-day Mudan District of Heze, Shandong). His family had been salt privateers for generations (with the salt trade officially monopolized by the state ever since the Anshi Rebellion), and the Huang family became wealthy from smuggling. It was said that Huang was capable in swordsmanship, riding, and archery, and was somewhat capable in writing and rhetoric. He used his wealth to take in desperate men who then served under him. He had at least one older brother, Huang Cun (黃存), and at least six younger brothers, Huang Ye (黃鄴) or Huang Siye (黃思鄴), Huang Kui (黃揆), Huang Qin (黃欽), Huang Bing (黃秉), Huang Wantong (黃萬通), and Huang Sihou (黃思厚).[5] He repeatedly participated in the imperial examinations, but was not able to pass them, and thereafter resolved to rebel against Tang rule.[6]

Rebellion

[edit]

Joining forces with Wang Xianzhi

[edit]Late in the Xiantong era (860–874) of Emperor Yizong, there were severe droughts and floods that caused terrible famine. Despite this, the Tang imperial government largely ignored the victims of these natural disasters—instead of granting tax exemptions for affected areas, taxes were increased to fund Emperor Yizong's luxurious lifestyle and military campaigns. As a result, survivors grouped themselves into bands and rose to resist Tang rule.

In 874, Wang Xianzhi (who, like Huang Chao, was a salt privateer) and Shang Junzhang (尚君長) raised an army at Changyuan (長垣, in modern Xinxiang, Henan). By 875, he had repeatedly defeated Xue Chong (薛崇), the military governor of Tianping Circuit (天平, headquartered in modern Tai'an, Shandong), in battle. Huang had by this point also raised several thousand men, and joined forces with Wang's now veteran troops.[6] By this time Emperor Yizong had died and his young son Emperor Xizong ruled.

Late in 876, Wang was sought to parlay his victories into a peaceful submission to Tang authority, in which he would be generously treated by the throne. This was being mediated by Tang official Wang Liao (王鐐), a close relation to chancellor Wang Duo, and Pei Wo (裴偓) the prefect of Qi Prefecture (蘄州, in modern Huanggang, Hubei). Under Wang Duo's insistence, Emperor Xizong commissioned Wang Xianzhi as an officer of the imperial Left Shence Army (左神策軍) and delivered the commission to Qi Prefecture. However, Huang, who did not receive a commission as part of this arrangement, angrily stated:[6]

"When we started the rebellion, we made a grand oath and we have marched through great distances with you. Now, you are going to accept this office and go to the Left Shence Army. What should these 5,000 men do?"

He battered Wang Xianzhi on the head, and the rebel soldiers also clamored against the arrangement. Wang Xianzhi, fearing the wrath of his own army, turned against Pei and pillaged Qi Prefecture. However, afterwards, the rebel army broke up into two groups, with one group following Wang Xianzhi and Shang Junzhang, and one group following Huang.[6]

Subsequent departure from Wang

[edit]Huang Chao subsequently roamed throughout central China, and his campaign took him into many engagements with Tang forces:

- In the spring of 877, Huang captured Tianping's capital Yun Prefecture (鄆州), killing Xue Chong, and then captured Yi Prefecture (沂州, in modern Linyi, Shandong).[7]

- In the summer of 877, he joined forces with Shang Junzhang's brother Shang Rang at Mount Chaya (查牙山, in modern Zhumadian, Henan). He and Wang Xianzhi then briefly joined forces again and put the Tang general Song Wei (宋威) under siege at Song Prefecture (宋州, in modern Shangqiu, Henan). However, the Tang general Zhang Zimian (張自勉) then arrived and defeated them, and they lifted the siege on Song Prefecture and scattered.[7]

- In winter 877, he pillaged Qi and Huang (黃州, in modern Wuhan, Hubei) Prefectures. The Tang general Zeng Yuanyu (曾元裕) defeated him, however, and he fled. He soon captured Kuangcheng (匡城, in modern Xinxiang) and Pu Prefecture (濮州, in modern Heze).[7]

In the spring of 878, Huang was besieging Bo Prefecture (亳州, in modern Bozhou, Anhui), when Wang Xianzhi was crushed by Zeng at Huangmei (黃梅, in modern Huanggang, Hubei) and killed. Shang Rang took the remnants of Wang's army and joined Huang at Bo Prefecture, and he offered the title of king to Huang. Huang, instead, claimed the title of Chongtian Dajiangjun (衝天大將軍, "Generalissimo Who Charges to the Heavens") and changed the era name to Wangba, to show independence from the Tang regime. He then captured Yi and Pu Prefectures again, but then suffered several defeats by Tang forces. He thus wrote the new military governor of Tianping, Zhang Xi (張裼), asking Zhang to ask for a Tang commission on his behalf. At Zhang's request, Emperor Xizong commissioned Huang as a general of the imperial guards, but ordered him to report to Yun Prefecture to disarm before he would report to the capital Chang'an. Faced with those conditions, Huang refused the offer. Instead, he attacked Song and Bian (汴州, in modern Kaifeng, Henan) Prefectures, and then attacked Weinan (衞南, in modern Puyang, Henan), and then Ye (葉縣, in modern Pingdingshan, Henan) and Yangzhai (陽翟, in modern Xuchang, Henan). Emperor Xizong thus commissioned troops from three circuits to defend the eastern capital Luoyang, and further ordered Zeng to head to Luoyang as well. With the Tang forces concentrating on defending Luoyang, Huang marched south instead.[7]

March to Lingnan

[edit]Huang Chao crossed the Yangzi River southwards and captured several prefectures south of the Yangzi—Qian (虔州, in modern Ganzhou, Jiangxi), Ji (吉州, in modern Ji'an, Jiangxi), Rao (饒州, in modern Shangrao, Jiangxi), and Xin (信州, in modern Shangrao). In fall 878, he then headed northeast and attacked Xuan Prefecture (宣州, in modern Xuancheng, Anhui), defeating Wang Ning (王凝), the governor of Xuanshe Circuit (宣歙, headquartered at Xuan Prefecture), at Nanling (南陵, in modern Wuhu, Anhui), but could not capture Xuan Prefecture, and therefore further headed southeast to attack Zhedong Circuit (浙東, headquartered in modern Shaoxing, Zhejiang), and then, via a mountainous route, Fujian Circuit (福建, headquartered in modern Fuzhou, Fujian) in winter 878. However, during this march, he was attacked by the Tang officers Zhang Lin (張璘) and Liang Zuan (梁纘), who were subordinates of Gao Pian, the military governor of Zhenhai Circuit (鎭海, headquartered in modern Zhenjiang, Jiangsu), and was defeated several times. As a result of these battles, a number of Huang's followers, including Qin Yan, Bi Shiduo, Li Hanzhi, and Xu Qing (許勍), surrendered to the Zhenhai troops. As a result, Huang decided to turn further south, toward the Lingnan region.[7]

By this point, Wang Duo had volunteered to oversee the operations against Huang, and Wang was thus made the overall commander of the operations as well as the military governor of Jingnan Circuit (荊南, headquartered in modern Jingzhou, Hubei). In reaction to Huang's movement, he commissioned Li Xi (李係) to be his deputy commander, as well as the governor of Hunan Circuit (湖南, headquartered in modern Changsha, Hunan), in order to block a potential northerly return route for Huang. Meanwhile, Huang wrote Cui Qiu (崔璆), the governor of Zhedong Circuit, and Li Tiao (李迢), the military governor of Lingnan East Circuit (嶺南東道, headquartered in modern Guangzhou, Guangdong), to ask them to intercede for him, offering to submit to Tang imperial authority if he were made the military governor of Tianping. Cui and Li Tiao relayed his request, but Emperor Xizong refused. Huang then directly made an offer to Emperor Xizong, requesting to be the military governor of Lingnan East. Under the opposition of the senior official Yu Cong, however, Emperor Xizong also refused. Instead, at the chancellors' advice, he offered to make Huang an imperial guard general. Huang, receiving the offer, was incensed by what he perceived to be an insult. In fall 879, he attacked Lingnan East's capital Guang Prefecture, capturing it after a one-day siege and taking Li Tiao captive. He ordered Li Tiao to submit a petition to Emperor Xizong on his behalf again, but this time, Li Tiao refused, so he executed Li Tiao.[7] Arab and Persian pirates[8] had previously sacked Guangzhou;[9] the port was subsequently closed for fifty years.[10] As subsequent relations were rather strained, their presence came to an end during Huang Chao's revenge.[11][12][13][14][15] Arab sources claim that the foreign Arab and Persian Muslim, Zoroastrian, Jewish, and Christian victims numbered tens of thousands. However, Chinese sources do not mention the event at all.[16][17][18][19] Mulberry groves in south China were ruined by his army, leading to a decline in silk exports along the Maritime Silk Road.[20]

Return to the North

[edit]However, as Huang Chao's army was in the Lingnan region, his soldiers were stricken by illnesses, and some 3–40% died. His key subordinates suggested that he march back north, and he agreed. He thus made rafts at Gui Prefecture (桂州, in modern Guilin, Guangxi) and took them down the Xiang River, reaching Hunan's capital Tan Prefecture (in modern Changsha, Hunan) in winter 879. He attacked Tan Prefecture and captured it in a day, and Li Xi fled to Lang Prefecture (朗州, in modern Changde, Hunan). Shang Rang then attacked Jingnan's capital Jiangling Municipality, where Wang Duo was. Wang panicked and fled as well, leaving the city to be defended by his officer Liu Hanhong, but as soon as Wang left the city, Liu mutinied, pillaged the city, and took his soldiers to become bandits.[7]

Huang himself followed Xiang's advance and went through Jiangling to attack Xiangyang, the capital of Shannan East Circuit (山南東道). He was, however, defeated by the joint forces of Shannan East's military governor Liu Jurong (劉巨容) and the imperial general Cao Quanzhen (曹全晸), who further pursued him all the way to Jiangling. However, Liu, concerned that if he captured Huang, the imperial government would no longer value him, called off the pursuit, and Cao also broke off his pursuit. Huang then headed east and attacked E Prefecture (鄂州, in modern Wuhan), and pillaged the 15 surrounding prefectures. As he did so, however, he was repeatedly repelled by Zhang Lin. As a result of Zhang's successes, the imperial government put Zhang's superior Gao Pian, who had by that point been transferred to Huainan Circuit (淮南, headquartered in modern Yangzhou, Jiangsu), in charge of the overall operations against Huang, replacing Wang. Many circuits thus sent troops to Huainan[7]

With his forces repeatedly defeated by Zhang and also suffering from plagues, Huang, then stationed at Xin Prefecture (信州, in modern Shangrao), decided to try to bribe his way out of his predicament. He thus submitted much gold to Zhang and wrote letters to plead with Gao, offering to submit to Tang imperial authority. Gao, who also wanted to use trickery himself to capture Huang, offered to recommend Huang as a military governor. Further, Gao, in order to monopolize the achievement, decided to return the supplementary troops from Zhaoyi (昭義, headquartered in modern Changzhi, Shanxi), Ganhua (感化, headquartered in modern Xuzhou, Jiangsu), and Yiwu (義武, headquartered in modern Baoding, Hebei) Circuits. As soon as he returned those troops, however, Huang broke off negotiations and challenged Zhang to a battle. Gao, in anger, ordered Zhang to engage, but this time, Huang decisively defeated Zhang in spring 880 and killed him in battle, throwing Gao into a panic.[7]

Huang, after defeating Zhang, then captured Xuan Prefecture, then, in summer 880, crossed the Yangtze River north at Caishi (采石, in modern Ma'anshan, Anhui), and put the Huainan defense outposts Tianchang (天長, in modern Chuzhou, Anhui) and Liuhe (六合, in modern Nanjing, Jiangsu) under siege, not far from Gao's headquarters at Yang Prefecture (揚州). Bi Shiduo, who was then serving as an officer under Gao, suggested that Gao engage Huang, but Gao was terrified of engaging Huang after Zhang's death, and instead sent urgent requests for aid to the imperial government. The imperial government, which had hoped that Gao would be successful in stopping Huang, was very disappointed and thrown into a panic itself. Emperor Xizong ordered the circuits south of the Yellow River to send troops to Yin River (溵水, a major branch of the Shaying River) to block off Huang's further advance, and also sent Cao and Qi Kerang, the military governor of Taining Circuit (泰寧, headquartered in modern Jining, Shandong), to intercept Huang. However, Cao was only given 6,000 men, and although he fought hard, he was ultimately unable to stop Huang's 150,000 men.[7]

At this point, a mutiny among the imperial armies further ended any imperial resistance at Yin River. This occurred as some 3,000 Ganhua soldiers were heading to Yin River to participate in the defense operations there, and they went through Xu Prefecture (許州, in modern Xuchang), the capital of Zhongwu Circuit (忠武). Despite the Ganhua soldiers' reputation for lack of discipline, Xue Neng (薛能) the military governor of Zhongwu, because he had been Ganhua's military governor before, believed that they would be obedient to him, so he allowed them to stay in the city. But that night, the Ganhua soldiers rioted over what they perceived to be the lack of supplies given to them. Xue met them and calmed them down, but this in turn caused the Zhongwu soldiers and the populace of Xu Prefecture to be angry at his lenient treatment of them. The Zhongwu officer Zhou Ji, himself then taking Zhongwu soldiers toward Yin River, thus turned his army around and attacked and slaughtered the Ganhua soldiers. His soldiers also killed Xue and Xue's family. Zhou then declared himself military governor. Qi, concerned that Zhou would attack him, withdrew from the area and returned to Taining Circuit. In response, the troops that other circuits had stationed at Yin River scattered, leaving the path wide open for Huang. Huang thus crossed the Huai River north, and it was said that starting from this point, Huang's army stopped pillaging for wealth, but forced more young men into the army to increase its strength.[7]

Capture of Luoyang and Chang'an

[edit]As winter 880 began, Huang Chao headed toward Luoyang and Chang'an, and issued a declaration that his aim was to capture Emperor Xizong to make Emperor Xizong answer for his crimes. Qi Kerang was put in charge of making a final attempt to stop Huang from reaching Luoyang. Meanwhile, though, the chancellors Doulu Zhuan and Cui Hang, believing that imperial forces would not be able to stop Huang from reaching Luoyang and Chang'an, suggested that Emperor Xizong prepare to flee to Xichuan Circuit (西川, headquartered in modern Chengdu, Sichuan), where Chen Jingxuan, the brother of the powerful eunuch Tian Lingzi, was military governor. Emperor Xizong, however, wanted to also make one last attempt to defend Tong Pass, between Luoyang and Chang'an, and therefore sent the imperial Shence Army (神策軍) officers Zhang Chengfan (張承範), Wang Shihui (王師會), and Zhao Ke (趙珂)—whose soldiers were ill-trained and ill-equipped, as the Shence Army soldiers' families were largely wealthy and were able to pay the poor and the sick to fill in for them—to try to defend it. Meanwhile, Luoyang fell quickly, and Qi withdrew to Tong Pass as well, and submitted an emergency petition stating that his troops were fatigued, hungry, and without supplies, with no apparent imperial response.[2]

Huang then attacked Tong Pass. Qi and Zhang initially resisted his forces for more than a day, but thereafter, Qi's troops, hungry and tired, scattered and fled. Zhang's final attempts to defend Tong Pass were futile, and it fell. Meanwhile, Tian had recruited some new soldiers, who were also ill-trained but relatively well-equipped, and sent them to the front, but by the time they reached there, Tong Pass had already fallen, and the troops from Boye Army (博野軍) and Fengxiang Circuit (鳳翔, headquartered in modern Baoji, Shaanxi), also sent to the front to try to aid Zhang, became angry at the good equipment (including warm clothes) that Tian's new soldiers had, and mutinied, instead serving as guides for Huang's forces. Emperor Xizong and Tian abandoned Chang'an and fled toward Xichuan Circuit on January 8, 881.[1] Later that day, Huang's forward commander Chai Cun (柴存) entered Chang'an, and the Tang general Zhang Zhifang welcomed Huang into the capital. Shang Rang issued a declaration proclaiming Huang's love for the people and urged the people to carry on their daily affairs, but despite Shang's assurance that the people's properties would be respected, Huang's soldiers were pillaging the capital repeatedly. Huang himself, briefly, lived at Tian's mansion, moving into the Tang palace several days later. He also ordered that Tang's imperial clan members be slaughtered.[2]

As Emperor of Qi

[edit]In and around Chang'an

[edit]Huang Chao then moved into the Tang palace and declared himself the emperor of a new state of Qi. He made his wife, Lady Cao, empress, while making Shang Rang, Zhao Zhang (趙璋), and the Tang officials Cui Qiu (崔璆) and Yang Xigu (楊希古) chancellors. Huang initially tried to simply take over the Tang imperial mandate, as he ordered that the Tang imperial officials of the fourth rank or lower (in Tang's nine-rank system) continue to remain in office, as long as they showed submission by registering with Zhao, removing only the third-rank or above officials. The Tang officials who would not submit were executed en masse.[2] Huang also tried to persuade Tang generals throughout the circuits to submit to him, and a good number of them did, including Zhuge Shuang (諸葛爽) (whom he made the military governor of Heyang Circuit (河陽, headquartered in modern Jiaozuo, Henan)), Wang Jingwu the military governor of Pinglu Circuit (平盧, headquartered in modern Weifang, Shandong), Wang Chongrong (whom he made the military governor of Hezhong Circuit (河中, headquartered in modern Yuncheng, Shanxi), and Zhou Ji (whom he made the military governor of Zhongwu Circuit) — although each of those generals eventually redeclared loyalty to Tang and disavowed Qi allegiances.[2][21] He also tried to persuade the former Tang chancellor Zheng Tian, the military governor of nearby Fengxiang Circuit (鳳翔, headquartered in modern Baoji, Shaanxi), to submit, but Zheng resisted, and when he sent Shang and Wang Bo (王播) to try to capture Fengxiang, Zheng defeated Qi forces that he sent in spring 881.[2]

In light of Zheng's victory over Qi forces, Tang forces from various circuits, including Zheng and his ally Tang Hongfu (唐弘夫), Wang Chongrong (who had turned against Qi by this point and redeclared his loyalty to Tang), Wang Chucun, the military governor of Yiwu Circuit, and Tuoba Sigong, the military governor of Xiasui Circuit (夏綏, headquartered in modern Yulin, Shaanxi), converged on Chang'an in summer 881, hoping to quickly capture it. With the people of Chang'an waging street warfare against Qi forces as well, Huang withdrew from the city — but as Tang forces entered Chang'an, they lost discipline and became bogged down in pillaging the city. Qi forces then counterattacked and defeated them, killing Cheng Zongchu (程宗楚) the military governor of Jingyuan Circuit (涇原, headquartered in modern Pingliang, Gansu) and Tang Hongfu, and forcing the other Tang generals to withdraw from the city. Huang reentered Chang'an and, angry at the people of Chang'an for aiding Tang forces, carried out massacres against the population. With Zheng subsequently forced to flee Fengxiang due to a mutiny by his officer Li Changyan, Tang forces in the region became uncoordinated and did not make another attempt to recapture Chang'an for some time.[2]

In spring 882, Emperor Xizong, then at Chengdu, commissioned Wang Duo to oversee the operations against Qi, and Wang positioned himself at LInggan Temple (靈感寺, in modern Weinan, Shaanxi). With Wang overseeing the operations, Tang forces began to converge again in Chang'an's perimeter area, and the areas controlled by Qi forces became limited to Chang'an and its immediate surroundings, as well as Tong (同州) and Hua (華州) Prefectures (both in modern Weinan). With farming completely disrupted by the warfare, a famine developed in the region, such that both Tang and Qi forces resorted to cannibalism.[2] By fall 882, the Qi general Zhu Wen, in charge of Tong Prefecture, had become unable to stand to Tang pressure and surrendered to Tang. By winter 882, Hua Prefecture also surrendered to Tang under the leadership of the officer Wang Yu (王遇), limiting Qi territory to Chang'an.[21]

However, Tang forces were still not making a true attempt to recapture Chang'an by this point. However, the ethnic Shatuo general Li Keyong — who had been a Tang renegade for years but who had recently resubmitted to Tang and offered to attack Qi on Tang's behalf, arrived at Tong Prefecture in winter 882 to join the other Tang forces.[2][21] In spring 883, Li Keyong and the other Tang generals defeated a major Qi force (150,000 men) commanded by Shang and approached Chang'an. In summer 883, Li Keyong entered Chang'an, and Huang was unable to resist him, and so abandoned Chang'an to flee east. With Tang forces again boggled down in pillaging the city, they were unable to chase Huang, and Huang was able to flee east without being stopped.[21]

March back east and death

[edit]Huang Chao headed toward Fengguo Circuit (奉國, headquartered in modern Zhumadian) and had his general Meng Kai (孟楷) attack Fengguo's capital Cai Prefecture. The military governor of Fengguo, Qin Zongquan, was defeated by Meng, and reacted by opening the city gates, submitting to Huang, and joining Huang's forces. Meng, after defeating Qin, attacked Chen Prefecture (陳州, in modern Zhoukou, Henan), but was surprised by a counterattack by Zhao Chou, the prefect of Chen Prefecture, and was killed in battle. Angered by Meng's death, Huang led his and Qin's forces and put Chen Prefecture under siege, but could not capture it despite a nearly 300-day siege. With his army low on food supplies, he allowed them to roam the nearby countryside, seizing humans and using them for food.[21]

Meanwhile, in spring 884, fearing that they would become Huang's next target, Zhou Ji, Shi Pu, the military governor of Ganhua Circuit, and Zhu Wen (whose name had been changed to Zhu Quanzhong by that point), the Tang military governor of Xuanwu Circuit (宣武, headquartered in modern Kaifeng, Henan), jointly sought aid from Li Keyong, who had been made the military governor of Hedong Circuit (河東, headquartered in modern Taiyuan, Shanxi). Li Keyong thus headed south to aid them. After Li Keyong joined forces with those sent by Zhou, Zhu, Shi, and Qi Kerang, they attacked and defeated Shang Rang at Taikang (太康, in modern Zhoukou) and Huang Siye at Xihua (西華, in modern Zhoukou as well). Huang Chao, in fear, lifted the siege on Chen and withdrew. With his encampments being destroyed in a flood, Huang Chao decided to head toward Xuanwu's capital Bian Prefecture. While Zhu was able to repel Huang's initial attacks, he sought emergency aid from Li Keyong. Li Keyong, catching Huang when he was about to cross the Yellow River north, launched an attack at Wangman Crossing (王滿渡, in modern Zhengzhou, Henan) and crushed his army. Shang surrendered to Shi, while a large number of other generals surrendered to Zhu. Li Keyong gave chase, and Huang fled to the east. During the chase, Huang's youngest son was captured by Li Keyong. Li Keyong's army became worn out during the chase, however, and he broke off the chase and returned to Bian Prefecture.[21]

Huang headed toward Taining's capital Yan Prefecture. Shi Pu's officer Li Shiyue (李師悅), along with Shang, engaged Huang at Yan Prefecture and defeated him, annihilating nearly the remainder of his army, and he fled into Langhu Valley (狼虎谷, in modern Laiwu, Shandong). On July 13, 884,[1] Huang's nephew Lin Yan (林言) killed Huang, his brothers, his wife, and his children, and took their heads to prepare to surrender to Shi. On his way to Shi's camp, however, he encountered Shatuo and Boye Army irregulars, who killed him as well and took the heads to present to Shi.[21] (However, according to an alternative account in the New Book of Tang, Huang, believing that it was the only way that any of his army could be saved, committed suicide after instructing Lin to surrender with his head.)[5]

Legend of possible escape

[edit]Some speculate that Lin Yan bringing the alleged heads of Huang Chao and others to Shi Pu was only a decoy to allow the real Huang Chao to escape. It was noted that Langhu Valley was over 500 li or 3–4 days away on a horseback from Shi's camp in Xu Prefecture, and decomposition would have already kicked in during the hot summer to make the faces unrecognizable. Moreover, Huang Chao had a number of brothers following him and the siblings likely resembled each other.

Legends popular during the ensuing Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period claim that Huang became a Buddhist monk following his escape. The Song dynasty scholar Wang Mingqing (王明清), for example, alleged in his book Huizhu Lu: "When Zhang Quanyi was the mayor (留守) of the Western Capital (i.e. Luoyang), he recognized Huang Chao from among the monks."[22]

Poetry

[edit]He wrote a few poems that were lyrical even when expressing anger and violence. One such line reads:

The capital's full of golden armored soldiers (滿城盡帶黃金甲)

This poem was used to describe his preparations for rebellion in an angry spirit. Later, this phrase was used for the Chinese name of the 2006 film Curse of the Golden Flower. The Hongwu Emperor, founder of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), wrote a similar poem.[23]

Legacy

[edit]Although Huang Chao was one of many rebel leaders in Chinese history, the impact of his rebellion can be compared to that of the Yellow Turban Rebellion (which fragmented the Eastern Han dynasty) or the Taiping Rebellion (which destabilized the Qing dynasty). Huang Chao's rebellion greatly weakened the Tang dynasty and it eventually led to its demise in 907 at the hands of Huang Chao's former follower Zhu Wen when Zhu usurped the throne from Emperor Ai and initiated several decades of chaotic civil war called the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period.

Political scientist Yuhua Wang argues that the Huang Chao rebellion marks a turning point not just in the Tang dynasty, but in Chinese imperial history, as the carnage in the capital region wiped out most of the great aristocratic families which had monopolized politics since the Han dynasty. From the subsequent Song dynasty onwards, the political bureaucracy of China relied on more dispersed regional gentry clans who rose to prominence through the imperial civil service examination system.[24]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Academia Sinica Chinese-Western Calendar Converter.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 254.

- ^ Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 256.

- ^ See, e.g., in general, Bo Yang, Outline of Chinese History (中國人史綱), vol. 2.

- ^ a b New Book of Tang, vol. 255, part 2.

- ^ a b c d Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 252.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 253.

- ^ Sluglett, Peter; Currie, Andrew (2014). Atlas of Islamic History. New York: Routledge. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-138-82130-9.

- ^ Welsh, Frank (1974), Maya Rao (ed.), A Borrowed Place: The History of Hong Kong, Kodansha International, p. 13, ISBN 978-1-56836-134-5

- ^ Welsh, Frank (1974). Maya Rao (ed.). A Borrowed Place: The History of Hong Kong. Kodansha International. p. 13. ISBN 1-56836-134-3.

- ^ Gabriel Ferrand, ed. (1922). Voyage du marchand arabe Sulaymân en Inde et en Chine, rédigé en 851, suivi de remarques par Abû Zayd Hasan (vers 916). Paris Éditions Bossard. pp. 76.

- ^ Sidney Shapiro (1984). Jews in old China: studies by Chinese scholars. Hippocrene Books. p. 60. ISBN 0-88254-996-0. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Rukang Tian; Ju-k'ang T'ien (1988). Male anxiety and female chastity: a comparative study of Chinese ethical values in Ming-Chʻing times. Brill. p. 84. ISBN 90-04-08361-8. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ William J. Bernstein (2009). A Splendid Exchange: How Trade Shaped the World. Grove Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-8021-4416-4. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Gernet 1996, p. 292.

- ^ Ray Huang (1997). China: a macro history. M.E. Sharpe. p. 117. ISBN 1-56324-730-5. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ "A History Of The Arrival And The Development Of Islam In Kedah". www.mykedah2.com. Archived from the original on 2012-05-29. Retrieved 2018-06-20.

- ^ mankind, International Commission for a History of the Scientific and Cultural Development of Mankind History of (May 24, 1994). History of Humanity: From the seventh to the sixteenth century. Routledge. ISBN 9780415093088 – via Google Books.

- ^ Lipman, Jonathan Neaman (May 24, 1997). Familiar Strangers: A History of Muslims in Northwest China. University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295976440 – via Google Books.

- ^ A Splendid Exchange. Grove/Atlantic, Inc. 2009. p. 86. ISBN 978-1-55584-843-9. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ a b c d e f g Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 255.

- ^ "英雄末路:自殺?他殺? 黃巢死因至今撲朔迷離". Archived from the original on 2014-09-24. Retrieved 2014-09-21.

- ^ "黃金甲歷史背景與劇情深度影評". Archived from the original on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2009-06-14.

- ^ Yuhua Wang (2022). The Rise and Fall of Imperial China. Princeton. pp. 79–80, 92, 96.[ISBN missing]

Sources

[edit]- Gernet, Jacques (1996), A History of Chinese Civilization (2nd ed.), New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-49781-7

Further reading

[edit]- Richard Bulliet; Pamela Crossley; Daniel Headrick; Steven Hirsch; Lyman Johnson (2014). The Earth and Its Peoples, Brief: A Global History. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1305147096.

- Victor Cunrui Xiong (2009). Historical Dictionary of Medieval China. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0810860537.

- Glen Dudbridge (2013). A Portrait of Five Dynasties China: From the Memoirs of Wang Renyu (880–956). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199670680.

- Ouyang, Xiu (2004). Richard L. Davis (ed.). Historical Records of the Five Dynasties. New York City: Columbia University Press.

- Mote, F.W. (1999). Imperial China 900–1800. Harvard University Press.[ISBN missing]