Aircraft hijacking

| Part of a series on |

| Terrorism |

|---|

Aircraft hijacking (also known as aircraft piracy, especially within the special aircraft jurisdiction of the United States, and informally as skyjacking) is the unlawful seizure of an aircraft by an individual or a group. In most cases, the pilot is forced to fly according to the orders of the hijackers. Occasionally, however, the hijackers have flown the aircraft themselves, such as the September 11 attacks of 2001. In at least three cases, the plane was hijacked by the official pilot or co-pilot.[1][2][3][4]

Unlike the typical hijackings of land vehicles or ships, skyjacking is not usually committed for robbery or theft. Most aircraft hijackers intend to use the passengers as hostages, either for monetary ransom or for some political or administrative concession by authorities. Motives vary from demanding the release of certain inmates (notably IC-814), highlighting the grievances of a particular community (notably AF 8969) to political asylum (notably ET 961). Hijackers also have used aircraft as a weapon to target particular locations (notably during the September 11, 2001 attacks).

Hijackings for hostages commonly produce an armed standoff during a period of negotiation between hijackers and authorities, followed by some form of settlement. Settlements do not always meet the hijackers' original demands. If the hijackers' demands are deemed too great and the perpetrators show no inclination to surrender, authorities sometimes employ armed special forces to attempt a rescue of the hostages (notably Operation Entebbe).

History

The first recorded aircraft hijack took place on February 21, 1931, in Arequipa, Peru. Byron Rickards, flying a Ford Tri-Motor, was approached on the ground by armed revolutionaries. He refused to fly them anywhere and after a 10-day standoff, Rickards was informed that the revolution was successful and he could go in return for giving one group member a lift to Lima. [5]

In the Fort Worth Star-Telegram daily newspaper (morning edition) 19 September 1970, J. Howard "Doc" DeCelles states that he was actually the victim of the first skyjacking in December 1929. He was flying a postal route for the Mexican company Transportes Aeras Transcontinentales, ferrying mail from San Luis Potosí to Toreon and then on to Guadalajara. "Doc" was approached by Gen. Saturnino Cedillo, governor of the state of San Luis Potosí and one of the last remaining lieutenants of Pancho Villa. Cedillo was accompanied by several other men. He was told through an interpreter he had no choice in the matter. "Doc" stalled long enough to convey the information to his boss, who told him to cooperate. He had no maps, but was guided by the men as he flew above Mexican mountains. He landed on a road as directed, and was held captive for several hours under armed guard. He eventually was released with a "Buenos" from Cedillo and his staff. DeCelles kept his flight log, according to the article, but he did not file a report with authorities. "Doc" went on to work for the FAA in Fort Worth after his flying career.[citation needed]

The world's first fatal hijacking occurred on 28 October 1939. Earnest P. “Larry” Pletch shot Carl Bivens, 39, a flight instructor who was offering Pletch lessons in a yellow Taylor Cub monoplane with tandem controls in the air after taking off in Brookfield, Missouri. Bivens, instructing from the front seat, was shot in the back of the head twice. “Carl was telling me I had a natural ability and I should follow that line,” Pletch later confessed to prosecutors in Missouri. "I had a revolver in my pocket and without saying a word to him, I took it out of my overalls and I fired a bullet into the back of his head. He never knew what struck him." The Chicago Daily Tribune called it “One of the most spectacular crimes of the 20th century, and what is believed to be the first airplane kidnap murder on record.” Because it occurred somewhere over three Missouri counties, and involved interstate transport of a stolen airplane, it raised questions in legal circles about where, by whom, and even whether he could be prosecuted. Ernest Pletch pleaded guilty and was sentenced to life in prison, where he died in June 2001.[6]

Between 1948 and 1957, there were 15 hijackings worldwide, an average of a little more than one per year. Between 1958 and 1967, this climbed to 48, or about five per year. The number dropped to 38 in 1968, but grew to 82 in 1969, the largest number in a single year in the history of civil aviation; in January 1969 alone, eight airliners were hijacked to Cuba.[7] Between 1968 and 1977, the annual average jumped to 41.

In 1973, the Nixon Administration ordered the discontinuance by the CIA of the use of hijacking as a covert action weapon against the Castro regime. Cuban intelligence followed suit. That year, the two countries reached an agreement for the prosecution or return of the hijackers and the aircraft to each other's country. The Taiwanese intelligence also followed the CIA's example vis-а-vis China.

These measures plus the improvement in Israel's relations with Egypt and Jordan, the renunciation of terrorism by the Palestine Liberation Organization, the on-going peace talks between the PLO and Israel, the collapse of the communist states in East Europe, which reduced the scope for sanctuaries for terrorists, and the more cautious attitude of countries such as Libya and Syria after the U.S. declared them State-sponsors of international terrorism, the collapse of ideological terrorist groups such as the Red Army Faction and the tightening of civil aviation security measures by all countries have arrested and reversed the steep upward movement of hijackings.

However, the situation has not returned to the pre-1968 level and the number of successful hijackings continues to be high - an average of 18 a year during the 10-year period between 1988 and 1997, as against the pre-1968 average of five.[3]

In the Dymshits–Kuznetsov hijacking affair on 15 June 1970, a group of Soviet refuseniks attempted to hijack a civilian aircraft in order to escape to the West, were caught and spent many years in Soviet prisons. This case is politically distinct in the sense that the government of Israel [citation needed] - which strongly denounced other cases of Aircraft hijacking (citation?) - endorsed this one and declared its participants to be heroes and martyrs for the Zionist cause (citation?). This was denounced as a double standard by left-wing critics such as then Knesset Member Charlie Biton.

On September 11, 2001, 19 al-Qaeda Islamic extremists hijacked American Airlines Flight 11, United Airlines Flight 175, American Airlines Flight 77, and United Airlines Flight 93 and crashed them into the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center, the southwestern side of the Pentagon building, and Stonycreek Township near Shanksville, Pennsylvania in a terrorist attack. The 2,996 death toll makes the hijackings the most fatal in history.

Military aircraft hijacking

A Pakistan Air Force T-33 trainer was hijacked on August 20, 1971 before Indo-Pakistani war of 1971 in Karachi when a Bengali instructor pilot, Flight Lieutenant Matiur Rahman, knocked out the young Pilot Officer Rashid Minhas with the intention of defecting to India with the plane and national secrets. On regaining consciousness in mid-flight, Rashid Minhas struggled for flight control as well as relaying the news of his hijack to the PAF base. In the end of the ensuing struggle he succeeded to crash his aircraft into the ground near Thatta on seeing no way to prevent the hijack and the defection. He was posthumously awarded Pakistan's highest military award Nishan-e-Haider (Sign of the Lion) for his act of bravery.[8][9][10][11][12] Matiur Rahman was awarded Bangladesh's highest military award, Bir Sreshtho, for his attempt to defect to join the civil war in East Pakistan (modern-day Bangladesh).[10]

Mystery hijacking

D. B. Cooper is perhaps the most famous hijacker of all time and also the case is the only unsolved hijacking in America's aviation history.[13]

Dealing with hijackings

Before the September 11, 2001 attacks, most hijackings involved the plane landing at a certain destination, followed by the hijackers making negotiable demands. Pilots and flight attendants were trained to adopt the "Common Strategy" tactic, which was approved by the FAA. It taught crew members to comply with the hijackers' demands, get the plane to land safely and then let the security forces handle the situation. Crew members advised passengers to sit quietly in order to increase their chances of survival. They were also trained not to make any 'heroic' moves that could endanger themselves or other people. The FAA realized that the longer a hijacking persisted, the more likely it would end peacefully with the hijackers reaching their goal.[14] The September 11 attacks presented an unprecedented threat because it involved suicide hijackers who could fly an aircraft and use it to deliberately crash the airplane into buildings for the sole purpose to cause massive casualties with no warning, no demands or negotiations, and no regard for human life. The "Common Strategy" approach was not designed to handle suicide hijackings, and the hijackers were able to exploit a weakness in the civil aviation security system. Since then, the "Common Strategy" policy in the USA and the rest of the world to deal with airplane hijackings has no longer been used.

Since the attacks, the situation for crew members, passengers and hijackers has changed. United Airlines Flight 93 crashed into a field as flight attendants and passengers—who had heard about the other three hijacked planes ramming into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon—fought hijackers who were likely flying to crash the plane either into the White House or the United States Capitol. As on Flight 93, crew members and passengers now have to calculate the risks of passive cooperation, not only for themselves but also for those on the ground. Later examples of active passenger and crew member resistance occurred when passengers and flight attendants of American Airlines Flight 63 from Paris to Miami on December 22, 2001, teamed up to help prevent Richard Reid from igniting explosives hidden in his shoes. Another example is when a few passengers and flight attendants teamed up to subdue Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab who attempted to detonate explosives sewn into his underwear aboard Northwest Flight 253 on December 25, 2009. Flight attendants and pilots now receive extensive anti-hijacking and self-defense training designed to thwart a hijacking or bombing.[15]

Informing air traffic control

To communicate to air traffic control that an aircraft is being hijacked, a pilot under duress should squawk 7500 or vocally, by radio communication, transmit "(Aircraft callsign); Transponder seven five zero zero." This should be done when possible and safe. An air traffic controller who suspects an aircraft may have been hijacked may ask the pilot to confirm "squawking assigned code." If the aircraft is not being hijacked, the pilot should not squawk 7500 and should inform the controller accordingly. A pilot under duress may also elect to respond that the aircraft is not being hijacked, but then neglect to change to a different squawk code. In this case, the controller would make no further requests and immediately inform the appropriate authorities. A complete lack of a response would also be taken to indicate a possible hijacking. Of course, a loss of radio communications may also be the cause for a lack of response, in which case a pilot would usually squawk 7600 anyway.[16]

On 9/11, the suicide hijackers did not make any attempt to contact ground control to inform anyone about their hijackings, nor engage in any dialogue or negotiations. However, the hijacker-pilot of Flight 11 and the ringleader of the terrorist cell, Mohamed Atta, mistakenly transmitted announcements to ATC, meaning to go through the Boeing 767. Also, Amy Sweeney and Betty Ong called the American Airlines office, telling the workers that Flight 11 was hijacked. 9/11 hijacker-pilot Ziad Jarrah aboard Flight 93 also made a similar error when he mistakenly transmitted announcements to Cleveland ATC about the hijacking.

Prevention

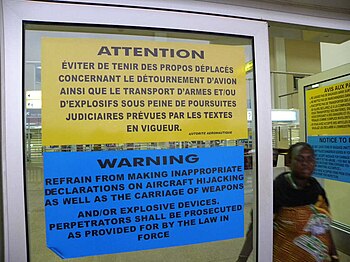

Cockpit doors on most commercial airliners have been strengthened and are now bullet resistant. In the United Kingdom, United States, Canada, Australia, Austria, the Netherlands and France, air marshals have also been added to some flights to deter and thwart hijackers. Airport security plays a major role in preventing hijackers. Screening passengers with metal detectors and luggage with x-ray machines helps prevent weapons from being taken on to an aircraft. Along with the FAA, the FBI also monitors terror suspects. Any person who is seen as a threat to civil aviation is banned from flying.

Shooting down aircraft

According to reports, U.S. fighter pilots have been trained to shoot down hijacked commercial airliners should it become necessary.[17] Other countries, such as India, Poland, and Russia have enacted similar laws or decrees that allow the shooting down of hijacked planes.[18] Polish Constitutional Court however, in September 2008, decided that the regulations were unconstitutional and dismissed them.[19]

India

In August 2005, India revealed its new anti-hijacking policy.[20] The policy came into force after the Cabinet Committee on Security (CCS) approved it. The main points of the policy are:

- Any attempt to hijack will be considered an act of aggression against the country and will prompt a response fit for an aggressor.

- Hijackers, if captured, will be sentenced to death.

- Hijackers will be engaged in negotiations only to bring the incident to an end, to comfort passengers and to prevent loss of lives.

- The plane will be shot down if it is deemed to become a missile heading for strategic targets.

- The plane will be escorted by armed fighter aircraft and will be forced to land.

- A grounded plane will not be allowed to take off under any circumstance.

The list of strategic targets is prepared by the Bureau of Civil Aviation in India. The decision to shoot down a plane is taken by CCS. However, due to the shortage of time, whoever – the prime minister, the defense minister or the home minister – can be reached first will take the call. In situations in which an aircraft becomes a threat while taking off – which gives very little reaction time – a decision on shooting it down may be taken by an Indian Air Force officer not below the rank of Assistant Chief of Air Staff (Operations).

Germany

In January 2005, a federal law came into force in Germany – the Luftsicherheitsgesetz – that allowed "direct action by armed force" against a hijacked aircraft to prevent a 9/11-type attack. However, in February 2006 the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany struck down these provisions of the law, stating such preventive measures were unconstitutional and would essentially be state-sponsored murder, even if such an act would save many more lives on the ground. The main reasoning behind this decision was that the state would effectively be taking the lives of innocent hostages in order to avoid a terrorist attack.[21] The Court also ruled that the Minister of Defense is constitutionally not entitled to act in terrorism matters, as this is the duty of the state and federal police forces. See the German Wikipedia entry, or [1]

The President of Germany, Horst Köhler, himself urged judicial review of the constitutionality of the Luftsicherheitsgesetz after he signed it into law in 2005.

International law issues

Tokyo Convention

The Tokyo Convention states in Article 11, defining the so-called unlawful takeover of an aircraft, that the parties signing the agreement are obliged, in case of hijacking or a threat of it, to take all the necessary measures in order to regain or keep control over an aircraft. The detailed analysis of the quoted article shows that in order of an unlawful takeover of an aircraft to take place, and at the same time to start the application of the convention, 3 conditions should be met:

- The hijacking or control takeover of an aircraft must be a result of unlawful use of violence or an attempt to use violence;

- An aircraft should be “in flight” (that is, according to Article 1, paragraph 3 of the Tokyo Convention, from the moment when power is applied for the purpose of take-off until the moment when the landing run ends);

- The unlawful act must be committed on board of an aircraft (that is, by a person being on board of an aircraft, e.g. a passenger or crew member. In case of an assault “from the outside”, such an offense would be treated as an act of aviation piracy)

However, even without the order of the captain, any member of crew or passenger, can take reasonable measures, when he or she has reasonable grounds to believe that such action is necessary to protect the safety of the aircraft, or of people or property therein. The captain may decide to disembark a suspected person on the territory of any country, where the aircraft would land, and that country must agree to that. (Article 8 and 12 of the Convention).

Hague Convention

The Convention for the suppression of unlawful seizure of Aircraft known as Hague convention came into force on October 14,1971 the convention under Article 1 defined the offences which may be covered by the convention.

Montreal Convention

United States administrative law definitions

In United States administrative law, the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Title 14, Aeronautics and Space, also known as the Federal Aviation Regulations, or FARs, are administered by the Federal Aviation Administration. Chapter II – Office of the Secretary, Department of Transportation (Aviation Proceedings) Subchapter A – Economics regulations, Part 243 – Passenger manifest information, Section 243.3 Definitions (14 CFR 243.3) says: Air piracy means any seizure of or exercise of control over an aircraft, by force or violence or threat of force or violence, or by any other form of intimidation, and with wrongful intent. Subparagraph (3) further defines an act of air piracy as an Air disaster.[22]

Popular culture

The Hollywood film Air Force One starring Harrison Ford recounts the fictional story of the hijacking of the famous aircraft by six Kazakh ultra-nationalist terrorists.[23]

The film Con Air, starring Nicolas Cage and John Malkovich, features scenes in which an aircraft is hijacked by the maximum-security prisoners on board.[24]

The Taking of Flight 847: The Uli Derickson Story was a made-for-TV film based on the actual hijacking of TWA Flight 847, as seen through the eyes of the chief flight attendant Uli Derickson.[25] Passenger 57 is a film starring Wesley Snipes as an airline security expert trapped on a passenger jet when terrorists seize control.[26]

Skyjacked is a 1972 film about a crazed Vietnam war veteran hijacking a Boeing 707 and demanding to be taken to Russia by the captain, Charlton Heston.[27]

The 1986 film The Delta Force starred Chuck Norris and Lee Marvin as leaders of an elite squad of special forces troops tasked with retaking a plane hijacked by Lebanese terrorists. [28]

The 2014 film Non-Stop starring Liam Neeson and Julianna Moore is another popular culture aircraft piracy film.

The 2006 film Snakes On a Plane is a fictional story about aircraft piracy through the in-flight release of crazed, venomous snakes.

See also

- Airport security

- CATSA

- Dymshits–Kuznetsov hijacking affair

- El Al#Hijacking

- FBI

- Federal Air Marshal Service

- Federal crime

- List of aircraft hijackings

- Palestinian political violence

- Terrorism

- Transportation Security Administration (TSA)

- United States Department of Homeland Security (DHS)

References

- ^ China Airlines Flight 334

- ^ "Air China pilot hijacks his own jet to Taiwan". CNN. 1998-10-28. Archived from the original on 2008-03-21. Retrieved 2007-01-25.

- ^ a b B. Raman (2000-01-02). "PLANE HIJACKING: IN PERSPECTIVE". South Asia Analysis Group. Retrieved 2007-01-25.

- ^ Ethiopian Airlines ET702 hijacking

- ^ 30 years later Rickards was again the victim of a failed hijacking attempt. A father and son boarded his Continental Airlines Boeing 707 in El Paso and tried to force him at gunpoint to fly the plane to Cuba hoping for a cash reward from Fidel Castro. FBI agents and police chased the plane down the runway and shot out its tires, averting the hijacking. See http://www.airdisaster.com/features/hijack/hijack.shtml

- ^ http://www.magbloom.com/PDF/bloom20/Bloom_20_Killer.pdf

- ^ McCartney, Scott. "The Golden Age of Flight" The Wall Street Journal, 22 July 2010.

- ^ http://www.paf.gov.pk/paf_shaheeds.html

- ^ John Pike. "PAF Kamra". Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- ^ a b "Pakistan". Ejection-history.org.uk. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- ^ "Pilot Officer Rashid Minhas". Pakistanarmy.gov.pk. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- ^ "Nishan-i-Haider laurelled Rashid Minhas' anniversary today". Samaa Tv. Retrieved 2012-01-29.

- ^ Gray, Geoffrey (2007-10-21). "Unmasking D.B. Cooper". New York magazine. ISSN 0028-7369. Retrieved 2011-04-24.

- ^ http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report_Ch3.htm

- ^ http://www.secure-skies.org/crewtraining.php

- ^ Aeronautical Information Manual, paragraph 6-3-4, "Special Emergency (Air Piracy)", Federal Aviation Administration, 1999

- ^ "US pilots train shooting civilian planes". BBC News. 10/3/2003. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Poland to down hijacked aircraft". BBC News. 2005-01-13. Retrieved 2010-03-30.

- ^ English translation of the judgement of the court

- ^ "India adopts tough hijack policy". BBC News, August 14, 2005.

- ^ English translation of the judgement by the court

- ^ "14 CFR 243.3 - Definitions". Legal Information Institute (LII). Cornell University Law School. 3 March 2013. Archived from the original on 2013-03-03. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ^ IMDb. "Air Force One". IMDb.

- ^ IMDb. / "Con Air". IMDb.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ IMDb. "The Taking of Flight 847: The Uli Derickson Story". IMDb.

- ^ IMDb. "Passenger 87". IMDb.

- ^ IMDb. "Skyjacked". IMDb.

- ^ IMDb. "The Delta Force". IMDb.