Campus sexual assault

This article or section may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards, as Article was renamed, but the content still reflects older scope. (July 2015) |

| Part of a series on |

| Violence against women |

|---|

| murder |

| Sexual assault and rape |

| Disfigurement |

| Other issues |

|

| International legal framework |

| Related topics |

Campus sexual assault is the sexual assault of a student attending an institute of higher learning, such as a college or university, though less than 40% of reported incidents occur on campus property.[1]

Sexual assault for higher education students occurs more frequently against women, but any gender can be affected. All ethnicities and social classes are affected. Many victims completely or partially blame themselves for the assault, or are embarrassed which may lead to underreporting. As remarked in one study, "Women generally do not report their victimization, in part because of self-blame or embarrassment."[2] According to other research, "myths, stereotypes, and unfounded beliefs about male sexuality, in particular male homosexuality" contribute to underreporting among males. In addition, "male sexual assault victims have fewer resources and greater stigma than do female sexual assault victims."[3]

While the rate of violent crime against students aged 18–24 in the United States declined significantly from 1995 to 2002, the rates of rape and sexual assault victimization largely remained unchanged.[4] Prevalence and incidence estimates vary based on methodology. A study by the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics has indicated that 6.1 incidents of sexual assault per 1000 female students (0.61%) occur annually in the U.S. A National Institute of Justice funded survey of two universities estimated that 19% of women and 6.1% of men had been victims of at least one completed or attempted sexual assault since entering college.[1]

Prevalence and incidence of rape and sexual assault

The majority of rape and other sexual assault victims do not report their attacks to law enforcement. As a result, sources that rely on police reports, such as the FBI's Uniform Crime Reports, tend to significantly underestimate the number of rapes and sexual assaults in a given year.[5] Researchers rely instead on victimization surveys to measure rape and sexual assault in order to assess the scope of sexual violence victimization.[citation needed]

Results of surveys measures of the prevalence and incidence of rape and sexual assault among college students offer widely disparate estimates of its prevalence. The National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) has estimated an annual prevalence rate as low as 0.43% in 2013 for all sexual assaults of women, with attempted or completed rape at approximately 0.35%.[6] Other research creates estimates ranging anywhere from 10%[1] to as many as 29%[7] of women having been victims of rape or attempted rape since starting college. Methodological differences, such as the method of survey administration, the definition of "rape" used, the wording of questions, and the time period studied contribute to these disparities.[7] There is currently no consensus on the best way to measure rape and sexual assault.[5]

National Crime Victimization Surveys

The National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) is a national survey administered a twice year by the United States Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS). The purpose of the NCVS is offer a uniform report of the incidence of crime including rape and sexual assault victimizations, in the general population.

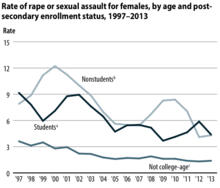

A 2014 assessment by Sinozich and Langton used longitudinal data from the NCVS to measure rape and sexual assault among college aged U.S. women from 1995 to 2013. Their findings indicated that rape, a subset of all sexual assault, had an incidence of 1.4 per 1,000 female students (0.1%) in 2013[6] during the period studied. The study also found that college aged women (regardless of enrollment status) were assaulted at a significantly higher rate than non-college age women, 4.3 per 1,000 (0.4%) per year versus 1.4 per 1,000 (0.1%) per year, but that women who were not enrolled in college were 1.2 times more likely to be assaulted than college aged women who were enrolled.[6]

The NCVS is one of the few national level, longitudinal sources of data on rape and sexual assault, and it has a relatively high response rate (88%) compared to other studies of sexual victimization. Data is collected using telephone interviews, which permits clarifying questions, and uses a bounded time frame of six months, limiting the likelihood that results are overestimated due to "telescoping" (the reporting of events occurring outside of a reference period as though they occurred within the specified period).[6]

However, results reported by the NCVS are consistently lower than studies using other methodologies, and researchers have charged that the question wording, context, and sampling methodology used on the NCVS leads a systematic underestimate of the incidence of rape and sexual assault.[5][8][9] A recent assessment of the NCVS methodology conducted by the National Research Council pointed to four flaws in the NCSV approach: the use of a sampling methodology that was inefficient in measuring low-incidence events like rape and sexual assault; the ambiguous wording questions related to sexual violence; the criminal justice definitions of assault; and the lack of privacy offered to survey respondents (phone interview vs. completely anonymous survey). The authors concluded that these flaws make it "highly likely that the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) is underestimating rape and sexual assault."[5] The NCVS also differs from other studies by including off campus students among its statistics. Since the risk of assault is higher for students living on campus, the 0.6% reported assault rate skews lower than what has been separately reported for campus environments.[10]

Campus Sexual Assault Survey (2007)

In 2007 the National Institute of Justice funded the Campus Sexual Assault (CSA) survey, a web-based survey of 6,800 undergraduates at two large universities using multiple explicitly worded questions about sexual victimization. According to the results, 19% of women and 6.1% of men had been victims of at least one completed or attempted sexual assault since entering college. The study's authors also found that the majority of women were assaulted while incapacitated, that perpetrators were usually friends or acquaintances rather than strangers and that Freshmen and Sophomores were at a higher risk for sexual assault than Juniors and Seniors.[1]

However, Christopher Krebs, the lead author of the CSA, cautions that the results from these two schools in no way nationally representative, noting, in a conversation with one reporter: "We don’t think one in five is a nationally representative statistic.” and “In no way does that make our results nationally representative.".[11] However, a 2015 Washington Post/Kaiser Health poll conducted on a nationally representative sample of college students also found that 1 in 5 women had been victims of a sexual assault since entering college.[12]

In a follow-up study in 2008, the authors of the 2007 Campus Sexual Assault Survey examined sexual violence experiences at historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs). 3,951 undergraduate women from four HBCUs were given the same questionnaire used in the 2007 CSA. The study found that 14.2% of women attending these schools had experienced a completed or attempted sexual assault, and 8.3% had been victims of rape. The authors noted that incapacitated sexual assault was rarer among HBCU compared to non-HBCU students, and suggested that the differences in prevalence rates seemed "to be driven entirely by a difference in the rate of incapacitated sexual assault, which is likely explained by the fact that HBCU women drink alcohol much less frequently than non-HBCU women".[13]

National College Women Sexual Victimization (NCWSV) survey (2000)

In 2000, The National Institute of Justice (NIJ) and the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) updated the 1997 National College Women Sexual Victimization (NCWSV) survey. In it, 4,446 American college women were chosen randomly and surveyed. The effort consisted of behaviorally specific questions that describe an incident in graphic language and cover the elements of a criminal offense, such as "Did someone make you have sexual intercourse by using force or threatening to harm you?" According to that survey, 1.7% of women had experienced a rape and another 1.1% had experienced an attempted rape.

The National Institute of Justice pointed out in a report that this single estimate does not take into account variation between semesters and calculated, with caveats, that it can climb to between one-fifth and one-quarter over the course of a school career. They caution, however, that "These projections are suggestive" and "To assess accurately the victimization risk for women throughout a college career, longitudinal research following a cohort of female students across time is needed."[14][15]

Emily Yoffe, writing for Slate noted that this approach is problematic, which the researchers also detail in their footnotes. It takes the 1.7% assault rate from the survey and makes mathematical projections that presume students are there for 60 months, and that their experience in the first year (the highest risk period) is the same for all 5 years. She then goes on to state "The one-fifth to one-quarter assertion would mean that young American college women are raped at a rate similar to women in Congo, where rape has been used as a weapon of war."[11]

Koss Study (1985)

In 1985, Mary P. Koss, a professor of psychology at Kent State University, conducted a national rape survey on college campuses in the United States, sponsored by the National Institute of Health and with administrative support from Ms. Magazine. The survey, administered on 32 college campuses across the USA, asked 3,187 female and 2,872 male undergraduate students about their sexual experiences since age 14. The survey included ten questions related to sexual coercion. Out of the 3,187 undergraduate women Koss surveyed, 207, or 6%, had been raped within the past year. 15.4 percent of Koss' female respondents had been raped since age 14, an additional 12.1 percent of female respondents had experienced attempted rape since age 14, and 4.4 percent of college men reported perpetrating legal rape since age 14.[8] The combined figure for rape and attempted rape of women since age 14, 27.5 percent, became known as the "one in four" statistic.[16]

According to Christina Hoff Sommers, a self-described "equity feminist" who is a critic of mainstream feminism, the Koss study and the oft-quoted "one in four" statistic is based upon flawed methodology. One of the three questions used by Koss to calculate rape prevalence was, "Have you had sexual intercourse when you didn't want to because a man gave you alcohol or drugs?" According to Sommers and professor Neil Gilbert, this wording left the door open for anyone who regretted a sexual liaison to be counted as a rape victim, even if neither partner thought of the situation as abusive, and noted that 73% of the respondents did not report having been raped when asked directly [16][17] Subsequent studies[citation needed] have derived similar results using reworded drug and alcohol questions, and found that most victims reported being emotionally and psychologically affected regardless of whether they classified an event as "rape".[2][18]

Other studies of the time, such as those by scholars Margaret Gordon and Linda George, found much lower measured rape prevalence,[16] with their research simply asking women if they had been raped rather than asking behaviorally specific questions. The use of multiple behaviorally specific questions in rape surveys has since become one accepted approach used by both academic researchers and multiple U.S. federal government agencies.[9]

Non-US studies

Campus sexual assault has received less attention from researchers outside the U.S.. Studies that have examined sexual assault experiences among college students in western countries other than the U.S. have found results similar to those found by American researchers. A 1993 study of a nationally representative sample of Canadian College students found that 28% of women had experienced some form of sexual assault in the preceding year, and 45% of women had experienced some form of sexual assault since entering college.[18] A 1991 study of 347 undergraduates in New Zealand found that 25.3% had experienced rape or attempted rape, and 51.6% had experienced some form of sexual victimization.[19] A 2014 study of students in Great Britain found that 25% of women had experienced some type of sexual assault while attending university and 7% of women had experienced rape or attempted rape as college students.[20]

Characteristics

Perpetrator demographics

Research by David Lisak found that serial rapists account for 90% of all campus rapes[21] with an average of six rapes each.[22][23] A 2015 study of male students led by Kevin Swartout at Georgia State University found that that four out of five perpetrators did not fit the model of serial predators.[24] Of the 1,084 respondents to a 1998 survey at Liberty University, 8.1% of males and 1.8% of females reported perpetrating unwanted sexual assault.[25]

Victim demographics

Research of American college students suggests that white women, prior victims, first-year students, and more sexually active women are the most vulnerable to sexual assault. Another study shows that white women are more likely than non-white women to experience rape while intoxicated, but less likely to experience other forms of rape. This high rate of rape while intoxicated accounts for white women reporting a higher overall rate of sexual assault than non-white women, although further research is needed into racial differences and college party organization.[15] Regardless of race, the majority of victims know the assailant. Black women in America are more likely to report sexual assault that has been perpetrated by a stranger.[26] Teenage girls[clarification needed] are more likely to think that stranger rape is more serious than other forms of rape.[27] Victims of rape are mostly between 10 and 29 years old, while perpetrators are generally between 15 and 29 years old.[28]

A 2007 National Institute of Justice study found that, in terms of perpetrators, about 80% of survivors of physically forced or incapacitated sexual assault were assaulted by someone that they knew.[29]

Acquaintance rape

Acquaintance rape is the most common form of rape. In the U.S., 78% of all sexual assaults are committed by acquaintances. Victims between 18 and 29 years old are the highest risk group for sexual assault. In half of acquaintance assault cases, the victim and rapist are somewhat familiar with one another, 24% were perpetrated by an intimate partner, and 2% by a relative. Sexual assault by an assailant upon a person he or she does not know was cited in 22% surveyed incidents among enrolled student respondents.[6] Date rape, a form of acquaintance rape, is a non-domestic rape committed by someone with whom the victim has been involved in some form of a romantic relationship.[30] Date rape constitutes the vast majority of reported rapes. It can occur between two people who know one another usually in social situations, between people who are dating as a couple and have had consensual sex in the past, between two people who are starting to date, between people who are just friends, and between acquaintances. It includes rape of co-workers, schoolmates, friends, and other acquaintances, providing they are dating.[31] Date rape is considered the most under reported crime on college campuses.[32] The term date rape is often used interchangeably with the terms ‘acquaintance rape’ and ‘hidden rape’ and has been identified as a problem in western society.[33]

Gang rape

Gang rape is a rape perpetrated by multiple offenders at once. The Bureau of Justice Statistics report that only 5% of all rape cases involve more than one offender.[6] Fifty-five to seventy percent of gang rape perpetrators belong to fraternities. Eighty-six percent of off-campus attempted rape or sexual assaults are at fraternity houses.[34] College gang rape tends to be perpetrated by middle- to upper-class men.[35]

There are higher incidents of gang rape within fraternities for many reasons: peer acceptance, alcohol use, the acceptance of rape myths and viewing women as sexualized objects, as well as the highly masculinized environment.[citation needed] The Neumann study found that fraternity members are more likely than other college students to engage in rape.[34] One cause for the apparent higher incidence of fraternity rape may be due to the fact that some colleges do not have complete control over the privately owned fraternity houses.[15] Although gang rape on college campuses is an issue, acquaintance, and party rape (a form of acquaintance rape where intoxicated people are targeted) are more likely to happen.[35]

Risk factors

Researchers have identified a variety factors that contribute to heightened levels of sexual assault on college campuses. Individual factors (such as alcohol consumption and attitudes toward women), environmental and cultural factors (such as peer group support for sexual aggression), as well inadequate enforcement efforts by campus police and administrators have been offered as potential causes.[36]

Influence of alcohol

Alcohol consumption is known to have effects on sexual behavior and aggression. During social interactions, alcohol consumption also encourages biased appraisal of a partner’s sexual motives, impairs communication about sexual intentions, and enhances misperception of sexual intent, effects exacerbated by peer influence about how to act when drinking.[37] The effects of alcohol at point of forced sex are likely to impair ability to rectify misperceptions, diminish ability to resist sexual advancements, and justifies aggressive behavior.[37] Alcohol provides justification for engaging in behaviors that are usually considered inappropriate. Studies[by whom?] have shown consistent alcohol use in reported cases of sexual and non-sexual violence. The increase of assaults on college campuses can be attributed to the social expectation that students participate in alcohol consumption. The peer norms on American college campuses are to drink heavily, to act in an uninhibited manner and to engage in casual sex.[38]

Various studies have concluded the following results:

- At least 47% of college students’ sexual assaults are associated with alcohol use[6]

- 74% of perpetrators and 55% of victims of rape of a nationally representative sample of college students had been drinking alcohol[37]

- Women whose partners abuse alcohol are 3.6 times more likely than other women to be assaulted by their partners[39]

- In 2013, more than 14,700 students between the ages of 18 and 24 were victims of alcohol-related sexual assault in the U.S.[6]

- In those violent incidents recorded by the police in which alcohol was a factor, about 9% of the offenders and nearly 14% of the victims were under age 21[40]

Some universities[who?] only hold men accountable for gaining consent even when both parties are intoxicated. In a recent lawsuit against Duke university, a Duke administrator, when asked whether verbal consent need be mutual when both participants are drunk, stated, "Assuming it is a male and female, it is the responsibility in the case of the male to gain consent before proceeding with sex."[41] Other institutions state only that a rape victim has to be "intoxicated" rather than "incapacitated" by alcohol or drugs to render consent impossible.[42]

Attitudes

Individual and peer group attitudes have also been identified as an important risk factor for the perpetration of sexual assault among college aged men in the United States. Both the self-reported proclivity to commit rape in a hypothetical scenario, as well as self-reported history of sexual aggression, positively correlate with the endorsement of rape tolerant or rape supportive attitudes in men.[43][44] Acceptance of rape myths – prejudicial and stereotyped beliefs about rape and situations surrounding rape such as the belief that "only promiscuous women get raped" or that "women ask for it" – are correlated with self reported past sexual aggression and with self-reported willingness to commit rape in the future among men.[45]

A 2007 study found that college-aged men who reported previous sexual aggression held negative attitudes toward women and gender roles, were more acceptant of using alcohol to obtain sex, were more likely to believe that rape was justified in some circumstances, were more likely to blame women for their victimization, and were more likely to view sexual conquest as an important status symbol.[46][47]

According to sociologist Michael Kimmel, rape-prone campus environments exist throughout several university and college campuses in North America. Kimmel defines these environments as "…one in which the incidence of rape is reported by observers to be high, or rape is excused as a ceremonial expression of masculinity, or rape as an act by which men are allowed to punish or threaten women."[48]

Clery Act and shifting approaches

For years, advocates for rape victims complained that colleges and universities tended to minimize the problems of sexual assault, as well as related campus security concerns. The best known articulation that rape and sexual assault as a broader problem was the 1975 book Against Our Will. The book broadened the perception of rape from a crime by strangers, to one that more often included friends and acquaintances, and raised awareness. As early as the 1980s, campus rape was considered an under-reported crime. Reasons included to the involvement of alcohol, reluctance of students to report the crime, and universities not addressing the issue.[49]

A pivotal change in how universities handle reporting stemmed from the 1986 rape and murder of Jeanne Clery in her campus dormitory. Her parents pushed for campus safety and reporting legislation which became the foundation for the The Jeanne Clery Disclosure of Campus Security Policy and Campus Crime Statistics Act. The Clery Act requires that all schools in the U.S. that participate in federal student aid programs implement policies for addressing sexual assault.[50][51]

A 2000 study by the National Institute of Justice found that only about a third of U.S. schools fully complied with federal regulations for recording and reporting instances of sexual assault, and only half offered an option for anonymous reporting of sexual assault victimization.[52] One recent study indicated that universities also greatly under-report assaults as part of the Clery Act except when they are under scrutiny. When under investigation, the reported rate by institutions rises 44%, only to drop back to baseline levels afterwards.[53]

Numerous colleges in the United States have come under federal investigation for their handling of sexual assault cases, described by civil rights groups as discriminatory and inappropriate.[54][55]

Student and organizational activism

In view of what they considered poor responses by institutions to protect women, some student and other activists groups started raising awareness of the threats and harm women experience on campus. The first "Take back the night" march took place in 1978 in San Francisco, and then spread to many college campuses.[56] SlutWalk is a more recent movement against sexual violence.[57]

Some individuals have become causes célèbre among activists.Emma Sulkowicz, a student at Columbia University, is known for her performance art Mattress Performance (Carry That Weight). Lena Sclove, a student at Brown University, made headlines for saying that a fellow student, who reportedly sexually assaulted her, was not sufficiently punished after he received a one-year suspension.[58] The man accused in her case has publicly disputed the report and was found not guilty by the criminal justice system. He has been found responsible under the university's preponderance of the evidence standard. Such cases have led to controversy and concerns regarding presumption of innocence and due process, and have also highlighted the difficulties that universities face in balancing the rights of the accuser and the rights of the accused when dealing with sexual assault complaints.[59][60][61] Both cases have led to further complaints of bias by the men against the universities (Title IX or civil) regarding how they handled the matters.[58][62]

One outside group, UltraViolet, has used online media tactics, including search engine advertisements, to pressure universities to be more aggressive when dealing with reports of rape. Their social media campaign uses advertisements that sometimes lead with "Which College Has The Worst Rape Problem?" and other provocative titles that appear in online search results for a targeted school's name.[63]

Obama administration efforts

In 2011, the United States Department of Education sent a letter, known as the "Dear Colleague" letter, to the presidents of all colleges and universities in the United States stating that Title IX requires schools to investigate and adjudicate cases of sexual assault on campus.[64] The letter also states that schools must adjudicate these cases using a "preponderance of the evidence" standard, meaning that the accused will be responsible if it is determined that there is at least a 50.1% chance that the assault occurred. The letter expressly forbade the use of the stricter "clear and convincing evidence" standard used at some schools previously. In 2014, a survey of college and university assault policies conducted at the request of the U.S. Senate found that more than 40% of schools studied had not conducted a single rape or sexual assault investigation in the past five years, and more than 20% had failed to conduct investigations into assaults they had reported to the Department of Education.[65]

In 2014, President Barack Obama established the White House Task Force to Protect Students from Sexual Assault, which published a report reiterating the interpretation of Title IX in the "Dear Colleague" letter and proposing a number of other measures to prevent and respond to sexual assault on campus, such as campus climate surveys and bystander intervention programs.[66][67] Shortly thereafter, the Department of Education released a list of 55 colleges and universities across the country that it was investigating for possible Title IX violations in relation to sexual assault.[68] As of early 2015, 94 different colleges and universities were under ongoing investigations by the U.S. Department of Education for their handling of rape and sexual assault allegations.[69]

Criticism

The Department of Education's approach toward adjudicating sexual assault accusations has been criticized for failing to consider the possibility of false accusations, mistaken identity, or errors by investigators. Critics claim that the "preponderance of the evidence" standard required by Title IX is not an appropriate basis for determining guilt or innocence, and can lead to students being wrongfully expelled. Campus hearings have also been criticized for failing to provide many of the due process protections that the United States Constitution guarantees in criminal trials, such as the right to be represented by an attorney and the right to cross-examine witnesses.[70]

The Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) has been critical of university definitions of consent that it considers overly broad. In 2011, FIRE criticized Stanford University after it held a male student responsible for a sexual assault for an incident where both parties had been drinking. FIRE said that Stanford's definition of consent, quoted as follows "A person is legally incapable of giving consent if under age 18 years; if intoxicated by drugs and/or alcohol;", was so broad that sexual contact at any level of intoxication could be considered non-consensual.[71][72][73] Writing for the Atlantic Magazine Conor Friedersdorf noted that a Stanford male who alleges he was sexually assaulted in 2015 and was advised against reporting it by on-campus sexual assault services, could have been subjected to a counterclaim based on Stanford policy by his female attacker who was drunk at the time.[74] FIRE was also critical of a poster at Coastal Carolina University, which stated that sex is only consensual if both parties are completely sober and if consent is not only present, but also enthusiastic. The FIRE argued that this standard converted ordinary lawful sexual encounters into sexual assault even while drinking is very common at most institutions.[75][76]

In May 2014, the National Center for Higher Education Risk Management, a law firm that advises colleges on liability issues, issued an open letter to all parties involved in the issue of rape on campus.[77] In it, NCHERM expressed praise for Obama's initiatives to end sexual assault on college campuses, and called attention to several areas of concern they hoped to help address. While acknowledging appreciation for the complexities involved in changing campus culture, the letter offered direct advice to each party involved in campus hearings, outlining the improvements NCHERM considers necessary to continue the progress achieved since the issuance of the "Dear Colleague" letter in 2011. In early 2014, the group RAINN (Rape and Incest National Network) wrote an open letter to the White House calling for campus hearings to be de-emphasized due to their lack of accountability for survivors and victims of sexual violence. According to RAINN, "The crime of rape does not fit the capabilities of such boards. They often offer the worst of both worlds: they lack protections for the accused while often tormenting victims."[78]

In October 2014, 28 members of the Harvard Law School Faculty co-signed a letter decrying the change in the way reports of sexual harassment are being processed.[79] The letter asserted that the new rules violate the due process rights of the responding parties. In February 2015, 16 members of the University of Pennsylvania Law School Faculty co-signed a similar letter of their own.[80]

Since the issuance of the "Dear Colleague" letter, a number of lawsuits have been filed against colleges and universities by male students alleging that their universities violated their rights over the course of adjudicating sexual assault accusations.[81] Xavier University entered into a settlement in one such lawsuit in April 2014.[82]

Other examples include:

- In October 2014, a male Occidental College student filed a Title IX complaint against the school after he was expelled for an alleged sexual assault. The assault occurred after a night of heavy drinking in which both parties were reported to have been extremely impaired. Attorney's for the accused student argued that the accuser's actions, such as sending a text message indicating an intent to have sex, and entering the accused students bedroom under her own power, indicated that the sex was consensual. The accuser, however, said she had no memory of much of the evening, and an outside adjudicator concluded that she was incapacitated and unable to consent to sex. A police investigation found there was insufficient evidence to charge the accused student with a crime.[83][84] The accused student, who was also very drunk the night in question, attempted to file a sexual assault claim against his accuser, but the university declined to hear his complaint because he would not meet with an investigator without an attorney present.[85]

- In March 2015, Federal regulators (OCR) opened an investigation on how Brandeis University handles sexual assault cases, stemming from a lawsuit where a male student was found responsible for sexual misconduct. The accused was not permitted to see the report created by the special investigator that determined his responsibility until after a decision had been reached.[86][87]

- In June 2015 an Amherst College student who was expelled for forcing a woman to complete an oral sex act sued the college for failing to discover text messages from the accuser that suggested consent. The accuser said she described the encounter as consensual because she wasn't "yet ready to address what had happened". The suit alleges that the investigation was "grossly inadequate". When student later learned of the messages, Amherst refused to reconsider the case.[88] In its response to the lawsuit, the school stated the process was fair and that the student had missed the 7 day window in which to file an appeal.[89]

- In July 2015 a California court ruled that the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) acted improperly by using a deeply flawed system to adjudicate a sexual assault allegation and sanctioning the accused based on a process that violated his rights. The student was not given adequate opportunity to challenge the accusations and the panel relied on information deliberately withheld from the student despite repeated requests. The judge also admonished a dean who had a conflict of interest, and had punitively increased the student's penalty without explanation each time he appealed.[90]

In response to concerns, in 2014 the White House Task Force provided new regulations requiring schools to permit the accused to bring advisers and be clearer about their processes and how they determine punishments. In addition to concerns about legal due process, which colleges currently do not have to abide, the push for stronger punishments and permanent disciplinary records on transcripts can prevent students found responsible from ever completing college or seeking graduate studies. Even for minor sexual misconduct offenses, the inconsistent and sometimes "murky" notes on transcripts can severely limit options. Mary Koss, a University of Arizona professor, co-authored a peer-reviewed paper in 2014 that argues for a “restorative justice” response — which could include counseling, close monitoring, and community service — would be better than the judicial model most campus hearing panels resemble.[91]

College programs

Some colleges and universities have taken additional steps to prevent sexual violence on campus. These include educational programs designed to inform students about risk factors and prevention strategies to avoid victimization, bystander education programs (which encourage students to identify and defuse situations that may lead to sexual assault), and social media campaigns to raise awareness about sexual assault.[52]

See also

- "A Rape on Campus", a now-discredited and withdrawn article on an alleged sexual assault at the University of Virginia

- Bullying in academia

- Campus Accountability and Safety Act

- Duke lacrosse case, a famous instance of a false rape accusation at Duke University

- The Hunting Ground

- Rape culture

- Rape in the United States#Jurisdiction

- Sexual harassment in education

- Violence against men

- Violence against women

References

- ^ a b c d "The Campus Sexual Assault Survey" (PDF). National Institute of Justice. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ^ a b Ellen R. Girden; Robert Kabacoff (2010). Evaluating Research Articles From Start to Finish. SAGE Publishing. pp. 84–92. ISBN 9781412974462.

- ^ Bullock, Clayton M; Beckson, Mace (April 2011). "Male victims of sexual assault: phenomenology, psychology, physiology". American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. 39 (2): 197–205. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- ^ Baum, Katrina. "Violent Victimization of College Students". US Department of Justice. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ^ a b c d Kruttschnitt, Candace; Kalsbeek, William D.; House, Carol C. (2014). Estimating the Incidence of Rape and Sexual Assault. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Sinozich, Sofi; Langton, Lynn. "Rape and Sexual Assault Victimization Among College-Age Females, 1995-2013". U.S. Department of Justice. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ^ a b Rennison, C. M.; Addington, L. A. (2014). "Violence Against College Women: A Review to Identify Limitations in Defining the Problem and Inform Future Research". Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 15 (3): 159–169. doi:10.1177/1524838014520724. ISSN 1524-8380.

- ^ a b Koss, Mary (1988). "Hidden Rape: Sexual Aggression and Victimization in a National Sample of Students in Higher Education". Rape and Sexual Assault. 2. Garland Publishing: 8.

- ^ a b Fisher, Bonnie (2004). "Measuring Rape Against Women: The Significance of Survey Questions". National Criminal Justice Reference Service.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Goldstein, Dana (12 December 2014). "The Dueling Data on Campus Rape". The Marshall Project. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ^ a b Yoffe, Yoffe (7 December 2014). "The College Rape Overcorrection". Slate. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ Anderson, Nick; Clement, Scott (12 June 2015). "1 in 5 college women say they were violated". Washington Post. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- ^ Krebs, C. P.; Barrick, K.; Lindquist, C. H.; Crosby, C. M.; Boyd, C.; Bogan, Y. (2011). "The Sexual Assault of Undergraduate Women at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs)". Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 26 (18): 3640–3666. doi:10.1177/0886260511403759. ISSN 0886-2605.

- ^ "The Sexual Victimization of College Women". Us Department of Justice. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ^ a b c Armstrong, E. A., Hamilton, L., Sweeny, B., Sexual Assault on Campus: A Multilevel, Integrative Approach to Party Rape. pp. 483–493

- ^ a b c Who Stole Feminism? (Simon & Schuster Inc., New York, 1994) by Christina Hoff Sommers, chapter 10, pp. 209-226. {excerpt here}.

- ^ Christina Hoff Sommers, Who Stole Feminism? How Women Have Betrayed Women, Simon and Schuster, 1994, 22. ISBN 0-671-79424-8 (hb), ISBN 0-684-80156-6 (pb), LCC HQ1154.S613 1994, p. 213

- ^ a b Schwartz, Martin (1999). "Bad Dates or Emotional Trauma? The Aftermath of Campus Sexual Assault". Violence Against Women. 5. Sage Publications: 251–271. doi:10.1177/10778019922181211. Cite error: The named reference "Schwartz" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Gavey, Nicola (1991). "Sexual victimization prevalence among New Zealand university students". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 59 (3): 464–466. doi:10.1037/0022-006x.59.3.464.

- ^ "Hidden Marks: A study of women student's experiences of harassment, stalking, violence, and sexual assault" (PDF). http://www.nus.org.uk/. National Union of Students. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website= - ^ Lisak, David (2008). "Understanding the Predatory Nature of Sexual Violence". Retrieved 10 June 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Lauerman, Connie (15 September 2004). "Easy targets". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ Lisak, David; Miller, Paul M. (February 2002). "Repeat rape and multiple offending among undetected rapists". Violence and Victims. 17 (1): 73–84. doi:10.1891/vivi.17.1.73.33638.

- ^ Swartout, Kevin M.; Koss, Mary P.; White, Jacquelyn W.; Thompson, Martie P.; Abbey, Antonia; Bellis, Alexandra L. (13 July 2015). "Trajectory Analysis of the Campus Serial Rapist Assumption". JAMA Pediatrics. American Medical Association. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0707. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- ^ Nicholson, Mary E.; Wang, Min Qi; Maney, Dolores; Yuan, Jianping; Mahoney, Beverly S.; Adame, Daniel D. (1998). "Alcohol Related Violence and Unwanted Sexual Activity on the College Campus". Faculty Publications and Presentations. Liberty University. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ Furtado, C., "Perceptions of Rape: Cultural, Gender, and Ethnic Differences" in Sex Crimes and Paraphilia Hickey, E.W. (ed.), Pearson Education, 2006, ISBN 0131703501, pp. 385–395.

- ^ McGowan, M.G., "Sex Offender Attitudes, Stereotypes, and their Implications" in Sex Crimes and Paraphilia Hickey, E.W. (ed.), Pearson Education, 2006, ISBN 0131703501, pp. 479–498.

- ^ Flowers, R.B., Sex Crimes, Perpetrators, Predators, Prostitutes, and Victims, 2nd Edition, p. 28.

- ^ "Rape on College Campus". Union College. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- ^ Curtis, David G. (1997). "Perspectives on Acquaintance Rape". The American Academy of Experts in Traumatic Stress, Inc.

- ^ Cambridge Police 97 crime report[dead link]

- ^ "K-State Perspectives". Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- ^ "Perspectives on Acquaintance Rape". Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- ^ a b Neumann, S., "Gang Rape: Examining Peer Support and Alcohol in Fraternities" in Sex Crimes and Paraphilia Hickey, E.W. (ed.), Pearson Education, 2006, ISBN 0131703501 pp. 397–407.

- ^ a b Thio, A., 2010. Deviant Behavior, 10th Edition

- ^ Armstrong, Elizabeth A.; Hamilton, Laura; Sweeney, Brian (2006). "Sexual Assault on Campus: A Multilevel, Integrative Approach to Party Rape". Social Problems. 53 (4): 483–499. doi:10.1525/sp.2006.53.4.483. ISSN 0037-7791.

- ^ a b c Abbey, A (2002). "Alcohol-related sexual assault: A common problem among college students" (PDF). Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 63 (2): 118–128. PMID 12022717.

- ^ Nicholson, M.E. (1998). "Trends in alcohol-related campus violence: Implications for prevention". Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 43 (3): 34–52.

- ^ Demetrios, N; Anglin, Deirdre; Taliaferro, Ellen; Stone, Susan; Tubb, Toni; Linden, Judith A.; Muelleman, Robert; Barton, Erik; Kraus, Jess F. (1999). "Risk factors for injury to women from domestic violence". The New England Journal of Medicine. 342 (25): 1892–1898. doi:10.1056/NEJM199912163412505. PMID 10601509.

- ^ "Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services". Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ^ "PA Duke senior sues the university after being expelled over allegations of sexual misconduct". Durham, N.C.: Indy Week. 2014. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- ^ "Stanford Trains Student Jurors That 'Acting Persuasive and Logical' is Sign of Guilt; Story of Student Judicial Nightmare in Today's 'New York Post'". FIRE.org. 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- ^ Widman, Laura; Olson, Michael (2012). "On the Relationship Between Automatic Attitudes and Self-Reported Sexual Assault in Men". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 42 (5): 813–823. doi:10.1007/s10508-012-9970-2. ISSN 0004-0002.

- ^ Koss, Mary P.; Dinero, Thomas E. (1988). "Predictors of Sexual Aggression among a National Sample of Male College Students". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 528 (1 Human Sexual): 133–147. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb50856.x. ISSN 0077-8923.

- ^ Lonsway, Kimberly A.; Fitzgerald, Louise F. (June 1994). "Rape Myths: In Review". Psychology of Women Quarterly. 18 (2): 151. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1994.tb00448.x. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ Burgess, G. H. (2007). "Assessment of Rape-Supportive Attitudes and Beliefs in College Men: Development, Reliability, and Validity of the Rape Attitudes and Beliefs Scale". Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 22 (8): 973–993. doi:10.1177/0886260507302993. ISSN 0886-2605.

- ^ Forbes, G. B.; Adams-Curtis, L. E. (2001). "Experiences With Sexual Coercion in College Males and Females: Role of Family Conflict, Sexist Attitudes, Acceptance of Rape Myths, Self-Esteem, and the Big-Five Personality Factors". Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 16 (9): 865–889. doi:10.1177/088626001016009002. ISSN 0886-2605.

- ^ Kimmel, Michael (2008). The Gendered Society Reader. Ontario: Oxford University Press. pp. 24, 34. ISBN 9780195421668.

- ^ Celis, William (22 January 1991). "Agony on Campus: What is Rape". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ "Campus Sexual Assault Victim's Bill of Rights". Cleryact.info. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ^ http://permanent.access.gpo.gov/lps66801/205521.pdf

- ^ a b "Sexual Assault on Campus: What Colleges and Universities are Doing About it" (PDF). National Institute of Justice.

- ^ Yung, Corey Rayburn (2015). "Concealing Campus Sexual Assault: An Empirical Examination" (PDF). Psychology, Public Policy, and Law. 21 (1). Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ^ "Feds launch investigation into Swarthmore's handling of sex assaults". Philadelphia Inquirer. 16 July 2013.

- ^ "Annual campus crime report may not tell true story of student crime". Daily Nebraskan. 16 July 2013.

- ^ Bergen, Raquel Kenney (19 June 2008). "Take back the night". In Renzetti, Claire M.; Edleson, Jeffrey L. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Interpersonal Violence. SAGE Publications. p. 707.

- ^ Leach, Brittany (2013). "Slutwalk and Sovereignty: Transnational Protest as Emergent Global Democracy". APSA 2013 Annual Meeting Paper. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- ^ a b Young, Cathy. "Exclusive: Brown University student Speaks Out on What It's Like to Be Accused of Rape". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ Harrison, Elizabeth. "Former Brown Student Denies Rape Allegations". NPR. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ^ Wilson, Robin. "Opening New Front in Campus-Rape Debate, Brown Student Tells Education Dept. His Side". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ^ Young, Cathy. "The Brown Case: Does it Still Look Like Rape". Minding the Campus. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ^ Weiser, Benjamin (23 April 2015). "Accused of Rape, a Student Sues Columbia Over Bias". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ^ Kingkade, Tyler (30 May 2014). "Activists Target The Princeton Review In Campus Rape Ad Campaign". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ "Dear Colleague Letter". United States Department of Education. 4 April 2011.

- ^ "Sexual Violence on Campus: How too many institutions of higher education are failing to protect students" (PDF). U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Financial & Contracting Oversight. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ^ Bidwell, Allie (22 January 2014). "White House Task Force Seeks to Tackle College Sexual Assault". U.S. News and World Report.

- ^ "The First Report of the White House Task Force to Protect Students from Sexual Assault" (PDF). April 2014.

- ^ Anderson, Nick (1 May 2014). "55 colleges under Title IX inquiry for their handling of sexual violence claims". The Washington Post.

- ^ Kingkade, Tyler. "Barnard College Joins List Of 94 Colleges Under Title IX Investigation". Huffington Post. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- ^ Grasgreen, Allie (12 February 2014). "Classrooms, Courts or Neither?". Inside Higher Ed.Other Sources:

- Taranto, James (6 December 2013). "An Education in College Justice". The Wall Street Journal.

- Hingston, Sandy (22 August 2011). "The New Rules of College Sex". Philadelphia.

- Grossman, Judith (16 April 2013). "A Mother, a Feminist, Aghast". The Wall Street Journal.

- Berkowitz, Peter (28 February 2014). "On College Campuses, a Presumption of Guilt". Real Clear Politics.

- Young, Cathy (6 May 2014). "Guilty Until Proven Innocent: The Skewed White House Crusade on Sexual Assault". Time.

- "On Sexual Harassment and Title IX". thefire.org. Foundation for Individual Rights in Education. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ^ Post Staff (20 July 2011). "The feds' mad assault on campus sex". The New York Post. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ^ Taranto, James (10 February 2015). "Drunkenness and Double Standards". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- ^ Admin (20 June 2014). "Stanford Trains Student Jurors That 'Acting Persuasive and Logical' is Sign of Guilt; Story of Student Judicial Nightmare in Today's 'New York Post'". TheFire.org. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ^ Friedersdorf, Conor. "On a Stanford Man Who Alleged a Sexual Assault". Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- ^ Schow, Ashe (22 July 2015). "Ever had drunk sex? That's rape, according to this university". Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- ^ Soave, Robby (21 July 2015). "HIT & RUN BLOG RSS Coastal Carolina University Thinks All Drunk Sex Is Rape: Requires Sobriety, Enthusiasm". Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- ^ Sokolow, Brett A. (27 May 2014). "An Open Letter to Higher Education about Sexual Violence from Brett A. Sokolow, Esq. and The NCHERM Group Partners" (PDF). The NCHERM Group, LLC.

- ^ "RAINN Urges White House Task Force to Overhaul Colleges' Treatment of Rape". Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network. 6 March 2014.

- ^ "Rethink Harvard's sexual harassment policy", The Boston Globe, 14 October 2014.

- ^ Volokh, Eugene (19 February 2015). "Open letter from 16 Penn Law School professors about Title IX and sexual assault complaints". Washington Post. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ^ Schow, Ashe, "Backlash: College men challenge 'guilty until proven innocent' standard for sex assault cases", Washington Examiner, 11 August 2014 | Other Sources:

- Van Zuylen-Wood, Simon (11 February 2014). "Expelled Swarthmore Student Sues College Over Sexual Assault Allegations". Philadelphia.

- Parra, Esteban (17 December 2013). "DSU student who was cleared of rape charges sues school". The News Journal.

- ^ Myers, Amanda Lee (24 April 2014). "Basketball star Wells settles suit against Xavier". Associated Press.

- ^ Jacobs, Peter (15 September 2014). "How 'Consensual' Sex Got A Freshman Kicked Out Of College And Started A Huge Debate". Business Insider. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ^ Kruth, Susan (27 March 2015). "'Esquire' Details Egregious Failures of Occidental Sexual Assault Case". TheFire.org. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ^ Dorment, Richard (25 March 2015). "Occidental Justice: The Disastrous Fallout When Drunk Sex Meets Academic Bureaucracy". Esquire Magazine. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ^ Moore, Mary. "Feds investigate Brandeis over treatment of sexual-assault allegations". Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ^ Anderson, Nick (20 August 2014). "Brandeis University: Questions on all sides". Washington Post. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- ^ Robinson, Walter V. (29 May 2019). "Expelled under new policy, ex-Amherst College student files suit". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- ^ Soave, Robby (20 July 2015). "Student Expelled for Rape Has Evidence He Was the Victim. Amherst Refuses to Review It". Reason.com. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- ^ Moyer, Justin Wm. (14 July 2015). "University unfair to student accused of sexual assault, says California judge". The Washington Post. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ^ Baker, Katie J.M. (20 November 2014). "The Accused". BuzzFeed. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

Further reading

- Bain, Kristen (September–October 2002). "Rape Culture on Campus". Off Our Backs, Vol. 32, No. 9/10. off our backs, inc. JSTOR 20837660.

- Armstrong, Elizabeth (2006). "Sexual Assault on Campus: A Multilevel, Integrative Approach To Party Rape". Social Problems 53.4:483-499. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- Fernandez, Sarah; Houlemarde, Mark (July 2012). "How to Progress From a Rape-Supportive Culture". Women in Higher Education. Retrieved 10 February 2013.