Catholic Church

Editing of this article by new or unregistered users is currently disabled. See the protection policy and protection log for more details. If you cannot edit this article and you wish to make a change, you can submit an edit request, discuss changes on the talk page, request unprotection, log in, or create an account. |

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

The Roman Catholic Church or Catholic Church (see Terminology, below) is the Christian Church in full communion with the Bishop of Rome, currently Pope Benedict XVI. It traces its origins to the original Christian community founded by Jesus, with its traditions first established by the Twelve Apostles and maintained through unbroken Apostolic Succession.

The Catholic Church is not only the largest Christian Church, but also the largest organized body of any world religion.[1] According to the Statistical Yearbook of the Church, the Church's worldwide recorded membership at the end of 2004 was 1,098,366,000, or approximately 1 in 6 of the world's population.[2] According to canon law, members are those who have been baptized in, or have been received into, the Catholic Church on making a profession of faith, provided they have not formally renounced membership.

While the Holy See of Rome is seen as central, the Catholic Church is a worldwide organization made up of one Western or Latin-Rite and 22 Eastern Rite particular Churches. The Church is divided into jurisdictional areas, usually on a territorial basis. The standard territorial unit is called, in the Latin Rite, a diocese, and in the Eastern Rites, an eparchy, each of which is headed by a bishop. At the end of 2004, the total number of all these jurisdictional areas or sees was 2755.[3]

Terminology

The Church described in this article has, throughout its history, used many names[4] to describe itself, the most common being simply "the Church".[5] It has not declared any of these names to be the name by which it should be known. However, in view of the sensibilities of other Churches, it refers to itself in its relations with them as either "the Catholic Church"[6] or "the Roman Catholic Church".[7]

Divergent usages attach a certain ambiguity to each of the terms Roman Catholic Church and Catholic Church. Some, in spite of the usage of the Holy See, apply the term Roman Catholic Church only to the Western or Latin Church, including those parts that follow a liturgical rite other than the Roman, but excluding the Eastern-Rite particular Churches that are in full communion with the Pope and thus part of the same Church. As for the term Catholic Church, Oriental Orthodox, Eastern Orthodox, Lutheran, Anglican, Old-Catholic, and other Christians claim to be, or to be part of, the Catholic Church. For their understandings of the term, see Catholicism, Catholic, and One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church.

Protestants were the first to use the term Roman Catholic to mean the whole of the Church faithful to the Bishop of Rome. However, Catholics themselves employed it as early as the seventeenth century, not only in English but also in Latin and French,[8] to profess their faith in the importance of communion with the see of Rome. However, this is generally not the Church's preferred term, because of its use by some to posit a distinction between "the Roman Catholic Church" and another supposed larger body called "the Catholic Church". Therefore, in its relations with other Christians, the Church prefers to use "the Catholic Church", rather than "the Roman Catholic Church." For internal use, the most common term is simply "the Church", which appears many hundreds of times in the Catechism of the Catholic Church, compared to 24 uses of "the Catholic Church" and no uses of the term "the Roman Catholic Church".

The name "Catholic Church" for this Church is formally accepted by some other Christian Churches, as shown in the joint documents referenced above, but most of these groups use "Roman Catholic Church" instead. In informal use, however, members even of the latter groups commonly understand "Catholic Church" as referring to it. As far back as 397, Saint Augustine of Hippo remarked that the term was generally thus understood even by those whom he qualified as heretics:

- … the name itself of Catholic, which, not without reason, amid so many heresies, the Church has thus retained; so that, though all heretics wish to be called Catholics, yet when a stranger asks where the Catholic Church meets, no heretic will venture to point to his own chapel or house.[9]

For simplicity and clarity, the simpler term "Catholic Church" is freely used within this article without suggesting acceptance of any claims implicit in that term, while "Roman Catholic Church" is used without endorsing the view that the Church in question is merely part of some larger "Catholic Church"; both terms are used here as alternative names for the entire Church "which is governed by the successor of Peter and by the bishops in communion with him."[10]

Origins and history

The Church traces its institution to Jesus and the Twelve Apostles, in particular Saint Peter, the leader of the Apostles, who is regarded as the first Pope.[11] The first known use of the term "Catholic Church" was in a letter by Ignatius of Antioch in 107, who wrote: "Where the bishop appears, there let the people be, just as where Jesus Christ is, there is the Catholic Church."[12] Additionally, Catholic writers list a number of references which point to at least a 'first among equals' status for the See of Rome from the very earliest times.[13]

Central to the doctrines of the Catholic Church is Apostolic Succession, the belief that the bishops are the spiritual successors of the original twelve apostles, through the historically unbroken chain of consecration (see: Holy Orders). The New Testament contains warnings against teachings considered to be only masquerading as Christianity,[14] and shows how reference was made to the leaders of the Church to decide what was true doctrine.[15] The Catholic Church teaches that it is the continuation of those who remained faithful to the apostolic and episcopal leadership and rejected false teachings.

After an initial period of sporadic but intense persecution, Christianity was legalized in the fourth century, when Constantine I issued the Edict of Milan in 313. Constantine was instrumental in the convocation of the First Council of Nicea in 325, which sought to address the Arian heresy and formulated the Nicene Creed which is used by the Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodoxy, and various Protestant churches. On 27 February 380, Emperor Theodosius enacted a law establishing Catholic Christianity as the official state religion of the Roman empire.[16]

Following the decline of the Roman Empire, the Church underwent a time of missionary activity and expansion. The success of monasticism gave rise to various centers of learning, most famously in Ireland and Gaul, and contributed to the Carolingian Renaissance. Later in the medieval period, cathedral schools developed into Universities (see University of Paris, University of Oxford, and University of Bologna), the direct ancestors of modern Western institutions of learning.

During the 11th century, through a gradual process over a number of decades, the Church underwent the Great Schism in which the Catholic Church and Eastern Orthodoxy divided over a number of administrative, liturgical, and doctrinal issues, most notably the Filioque and papal primacy of jurisdiction. Both the Second Council of Lyons (1274) and the Council of Basel (1439) attempted to reunite the Churches, but in both cases the Orthodox rejected the councils. The Catholic Church and Eastern Orthodoxy remain in schism to the present day, although excommunications were lifted in 1965, and efforts to end the schism continue. Some Eastern churches have since been reunited with the Catholic Church, acknowledging the primacy of the pope, and together form the Eastern Catholic (sometimes referred to as "Uniate") Churches.

Beginning in 1092 the Crusades, a series of military campaigns, especially those in the Holy Land and sanctioned by the Papacy, began under the pontificate of Urban II in response to pleas from the Byzantine Emperor Alexis I for aid against Turkish expansion. The actions of the crusaders in this and subsequent crusades, such as the sacking of Constantinople in the Fourth Crusade, would become the subject of much controversy.

Beginning around 1184, and continuing through the Reformation, a number of historical movements involving the Catholic Church, broadly referred to as the Inquisition, were aimed at securing religious and doctrinal unity within Christianity through conversion, and sometimes persecution, of alleged heretics. A conviction of heresy, seen as treason against Christendom, could involve penalties ranging from a fine to a sentence of capital punishment such as burning at the stake. For an example of the rarity of this sentence, from 1540 to 1700 of all the cases brought before the Spanish Inquisition only 2-3% per year resulted in execution, lower than virtually any secular court of the time.[17] Historians distinguish between the Medieval Inquisition, the Spanish Inquisition, the Roman Inquisition, and Portuguese Inquisition as distinct historical events. The extent of the Inquisition's activity, and particularly the exact number of deaths, has been the subject of much subsequent propaganda.

The second great rift in the history of Christianity was the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century, in which various groups repudiated the primacy of the pope, various other Catholic doctrines and practices as well as abuses (such as simony) common at the time. Reformers within the Catholic Church launched the Counter Reformation, a period of doctrinal clarification, reform of the clergy and the liturgy, and re-evangelization begun by the Council of Trent.

The Council of Trent and its reforms provided the theme for the next 300 years of Catholic history. The period lay an emphasis on catechesis and missionary work, in which the Jesuit and Franciscan orders were prominent. Catholicism spread worldwide, at pace with European colonialism: to The Americas, Asia, Africa and Oceania. The 18th and 19th century Church found itself facing not only the teachings of Protestantism, but also Enlightenment and Modernist teachings about the nature of the human person, the state, and morality. With the coming of the Industrial Revolution, and the increased concern about the conditions of urban workers, 19th and 20th century popes issued encyclicals (notably Rerum Novarum) explicating Catholic Social Teaching.

The First Vatican Council (1869–1870) affirmed the doctrine of papal infallibility which Catholics hold to be in continuity with the history of Petrine supremacy in the Church, but Eastern Orthodox and Protestant churches consider it a theological innovation.

The Second Vatican Council (1962–1965) was convened by Pope John XXIII primarily as a pastoral but authoritative council, to make the historic teachings of the Catholic Church clear to the modern world. It issued documents on a number of topics, including the nature of the Church, the mission of the laity, and religious freedom. It also issued directions for a revision of the liturgy, the implementation of which resulted in, among other things, the celebration of Mass and the other sacraments in the living language of the people as well as in Latin, although some hold that the Council intended Latin to have priority.

Beliefs

The core beliefs of the Catholic Church are shared by the majority of other Trinitarian Christian groups. Its catechesis makes use of the Nicene Creed and the Apostles' Creed, which are accepted also by most major Christian denominations. The Catechism of the Catholic Church (964 pages in the Latin edition) gives a rather detailed account of its beliefs. The Compendium of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, first published in 2005 and in English in 2006, is a much more concise version of the Catechism, in question and answer form.

Catholics place particular importance on the Church as an institution founded by Christ and kept from doctrinal error by the presence and guidance of the Holy Spirit, and as the font of salvation for humanity. The seven sacraments, of which the most important is the Eucharist, are of prime importance in obtaining salvation.

Scripture and Tradition

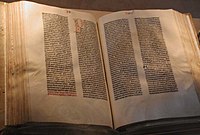

The principal sources for the teachings of the Catholic Church are the Sacred Scriptures and Sacred Tradition. The original language of most of the Old Testament is Hebrew or Aramaic, but several books or portions of books were written in Greek. The New Testament was also written in Greek.

In his 1943 encyclical letter, Divino Afflante Spiritu, Pope Pius XII encouraged Biblical scholars to study diligently these original languages and other cognate languages, so as to arrive at a deeper and fuller knowledge of the meaning of the sacred texts, stating that "the original text ... having been written by the inspired author himself, has more authority and greater weight than any even the very best translation, whether ancient or modern."[18]

There is a variety of sources for knowledge of Sacred Tradition, originally passed from the apostles in the form of oral tradition. Many of the writings of the Early Church Fathers reflect teachings of Sacred Tradition, such as apostolic succession.

Nature of God

Catholicism is monotheistic: it acknowledges that God is one, eternal, all-powerful (omnipotent), all-knowing (omniscient) and omnipresent (present in all places at all times). God exists as distinct from and prior to his creation (that is, everything which is not God, and which depends directly on him for existence) and yet is still present intimately in his creation. In the First Vatican Council the Church taught that, while by the natural light of human reason God can be known in his works as origin and end of all created things,[19] God has also chosen to reveal himself and his will supernaturally in the ways indicated in the Letter to the Hebrews 1:1–2.

Catholicism is also Trinitarian: it believes that, while God is one in nature, essence, and being, this one God exists in three divine persons, each identical with the one essence, whose only distinctions are in their relations to one another: the Father's relationship to the Son, the Son's relationship to the Father, and the relations of both to the Holy Spirit, constitute the one God as a Trinity.

A Catholic is baptized in the name (singular) of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit — not three gods, but one God subsisting in three Persons. While sharing in the one divine essence, the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are distinct, not simply three "masks" or manifestations of one Person. The faith of the Church and of the individual Christian is based on a relationship with these three Persons of the one God.

The Catholic Church believes that God has revealed himself to humanity as Father to his only-begotten Son, who is in an eternal relationship with the Father: "No one knows the Son except the Father, just as no one knows the Father except the Son and those to whom the Son chooses to reveal Him."[20]

Catholics believe that God the Son, the Divine Logos, the second of the three Persons of God, became incarnate as Jesus Christ, a human being, born of the Virgin Mary. He remained truly divine and was at the same time truly human. In what he said, and by how he lived, he taught all people how to live, and revealed God as Love, the giver of unmerited favours or Graces.

After Jesus' crucifixion and resurrection, his followers, foremost among them the Apostles, spread more and more extensively their faith with a vigour that they attributed to the presence of the Holy Spirit, the third of the three Persons of God, sent upon them by Jesus.

Humanity's separation from God

Human beings, in Catholic belief, were originally created to live in union with God. Through the disobedience of the first humans, that relationship was broken and sin and death came into the world.[21] The Fall left humans in a state called original sin, that is, separated from their original state of intimacy with God which carried into death through the idea of the individual human soul being immortal. But when Jesus came into the world, being both God and man, he was able through his sacrifice to reconcile humanity with God. By becoming one in Christ, through the Church, humanity was once again capable of intimacy with God but also offered a much more amazing gift: participation in the Divine Life on Earth, which will reach its fullness in heaven in the Beatific Vision.

The Church

The Church is, as scripture states, "the body of Christ,"[22] and Catholics teach that it is one united body of believers both in heaven and on earth. There is therefore only one true, visible and physical Church, not several. And to this one Church, originally founded by Peter and the Apostles, Jesus gave a mandate to be the authoritative teacher and guardian of the faith. To transmit Christ's divine revelation, the apostles were given the mandate to "preach the Gospel," which they performed both orally and in writing, and which they preserved by leaving bishops as their successors. Thus, the Catechism states "the apostolic preaching, which is expressed in a special way in the inspired books, was to be preserved in a continuous line of succession until the end of time. This living transmission, accomplished in the Holy Spirit, is called Tradition, since it is distinct from Sacred Scripture, though closely connected to it." [23] The Church is also a fount of divine grace which is administered through the sacraments (see below). The Church claims infallibility in teaching the faith, based on Jesus' scriptural promises to remain with his Church always,[24] and to maintain it in truth through the Holy Spirit.[25] Furthermore, Jesus promised divine protection to the teachings and judgements of the Apostles,[26] and those who succeeded them in their teaching office (i.e. the bishops). Moreover, Jesus set up the Church as the final arbiter between all believers:[27] "And if he refuses to listen to them, tell it to the church; and if he refuses to listen even to the church, let him be to you as a Gentile and a tax-gatherer."[28] In this, it bases its doctrines both on the written Apostolic record, The New Testament, and upon the oral traditions passed down from the Apostles to their successors (the bishops) through the continuous witness of the Church.[29]

Section 8 of the Second Vatican Council's Decree on the Church, Lumen Gentium states that "the one Church of Christ which in the Creed is professed as one, holy, catholic and apostolic" subsists "in the Catholic Church, which is governed by the successor of Peter and by the bishops in communion with him."[10] (The term successor of Peter refers in Catholic understanding to the Bishop of Rome, the Pope.)

The Catechism of the Catholic Church, 85 states that authentic interpretation of the Word of God is entrusted to the living Magisterium of the Church, namely the bishops in communion with the successor of Saint Peter.[30] Catholic theology places the authoritative interpretation of Scripture in the hands of the consistent judgment of the Church down the ages (what has always and everywhere been taught) rather than the private judgment of the individual. The Magisterium does, however, encourage its flock to read Sacred Scripture.

According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church, "the Church's first purpose is to be the sacrament of the inner union of men with God." Thus the Church's "structure is totally ordered to the holiness of Christ's members."[31]

Salvation

The Church teaches that salvation to eternal life is God's will for all people, and that God grants it to sinners as a free gift, a grace, through the sacrifice of Christ. "With regard to God, there is no strict right to any merit on the part of man. Between God and us there is an immeasurable inequality, for we have received everything from him, our Creator." [32] It is God who justifies, that is, who frees from sin by a free gift of holiness (sanctifying grace, also known as habitual or deifying grace). We can either accept the gift God gives through faith in Jesus Christ[33] and through baptism,[34] or refuse it. Human cooperation is needed, in line with a new capacity to adhere to the divine will that God provides.[35] The faith of a Christian is not without works, otherwise it would be dead.[36] In this sense, "by works a man is justified, and not by faith alone,"[37] and eternal life is, at one and the same time, grace and the reward given by God for good works and merits.[38] Faith, and subsequently works, are a result of God's grace - thus, it is only because of grace that the believer can be said to "merit" salvation.

The Roman Catholic Church teaches that through the graces Jesus won for humanity by sacrificing himself on the cross, salvation is possible even for those outside the visible boundaries of the Church. Christians and even non-Christians, if in life they respond positively to the grace and truth that God reveals to them through the mercy of Christ, may be saved. This may sometimes include awareness of an obligation to become part of the Catholic Church. In such cases, "whosoever, therefore, knowing that the Catholic Church was made necessary by Christ, would refuse to enter or to remain in it, could not be saved."[39]

Catholic life

Catholics are obliged to endeavour to be true disciples of Jesus. They seek forgiveness of their sins and follow the example and teaching of Jesus. They believe that Jesus has provided seven sacraments which give Grace from God to the believer.

Unless a Catholic dies in unrepented mortal sin, which is remitted in the Sacrament of Penance, it is believed that person has God's promise of inheriting eternal life. Before entering heaven, some undergo a purification, known as Purgatory.

Catholics believe that God works actively in the world. Catholics grow in grace through participation in the sacramental life of the Church, and through prayer, the work of mercy, and spiritual disciplines such as fasting and pilgrimage.

Prayer for others, even for enemies and persecutors is a Christian duty.[41] Catholics say there are four types of prayer: adoration, thanksgiving, contrition, and supplication. Catholics may address their requests for the intercession of others not only to people still in earthly life, but also to those in heaven, in particular the Virgin Mary and the other Saints. As Mother of Jesus, the Virgin Mary is also considered to be the spiritual mother of all Catholics.

Catholic social teaching

Catholic teachings stress forgiveness, doing good for others, especially those most in need, and the sanctity of life. Catholics were pacifists in the earliest days of the Church, as witnessed by the fact that Christians were forbidden to join the Roman Army. This was part of the cause of their political persecution in the empire.[42] Today, however, only some Catholics hold that position, with various analyses of the "just war theory" more widely held. It should be noted that the purpose of the Catholic "just war" criteria is to prevent and limit war rather than to justify it.[43]

Capital punishment, though it has not been absolutely condemned by the Church, has come under increasing criticism by theologians and Church leaders. Pope John Paul II, for instance, opposed capital punishment in all instances as being immoral, because there are other options for punishment and deterrence in the modern world. He, along with most other modern Catholic theologians, held that if capital punishment was ever moral—a position some dispute—it would only be justifiable when there was no other option for the protection of the lives of others. After four years of consultations with the world's Catholic bishops, John Paul II wrote that execution is only appropriate "in cases of absolute necessity: in other words, when it would not be possible otherwise to defend society. Today however, as a result of steady improvements in the organization of the penal system, such cases are very rare, if not practically non-existent."[44] This position is also held today by Avery Cardinal Dulles, Msgr. William Smith, Germain Grisez and other Catholic moral theologians.

Catholic teachings on human life and sexuality

The Catholic Church affirms the sanctity of all human life, from conception to natural death. The Church believes that each person is made in the "image and likeness of God," and that human life should not be weighed against other values such as economy, convenience, personal preferences, or social engineering. Therefore, the Church opposes activities that they believe destroy or devalue divinely created life, including euthanasia, eugenics and abortion.

The Church teaches that Manichaeism, the belief that the spirit is good while the flesh is evil, is a heresy. Therefore, the Church does not teach that sex is sinful or an impairment to a grace-filled life. As God created the human body in his own image and likeness, and because he found everything he created to be "very good,"[46] then the human body and sex must likewise be good. The Catechism teaches that "the flesh is the hinge of salvation."[47]

Pope John Paul II's first major teaching was on the Theology of the Body. Over the course of five years he elucidated a vision of sex that was not only positive and affirming but was about redemption, not condemnation. He taught that by understanding God's plan for physical love we could understand "the meaning of the whole of existence, the meaning of life."[48] "The body, and it alone, is capable of making visible what is invisible: the spiritual and divine. It was created to transfer into the visible reality of the world the mystery hidden since time immemorial in God, and thus to be a sign of it."[45]

Liturgy

The Catholic Church is fundamentally liturgical in its public life of worship. Liturgy is derived from the Greek for "work of the people." The Second Vatican Council stated "for the liturgy, 'through which the work of our redemption is accomplished,' most of all in the divine sacrifice of the Eucharist, is the outstanding means whereby the faithful may express in their lives, and manifest to others, the mystery of Christ and the real nature of the true Church."[49]

Sacraments

The Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1131 teaches: "The sacraments are efficacious signs of grace, instituted by Christ and entrusted to the Church, by which divine life is dispensed to us. The visible rites by which the sacraments are celebrated signify and make present the graces proper to each sacrament. They bear fruit in those who receive them with the required dispositions."

The seven sacraments are:

- Baptism

- Eucharist

- Confirmation

- Penance, also called Confession and Reconciliation

- Anointing of the Sick, formerly but no longer officially called Extreme Unction

- Holy Orders

- Matrimony

Devotional life of the Church

In addition to the sacraments, instituted by Christ, there are many sacramentals, sacred signs (rituals or objects) that derive their power from the prayer of the Church. They involve prayer accompanied by the sign of the cross or other signs. Important examples are blessings (by which praise is given to God and his gifts are prayed for), consecrations of persons, and dedications of objects to the worship of God. Popular devotions are not strictly part of the liturgy, but if they are judged to be authentic, the Church encourages them. They include veneration of relics of saints, visits to sacred shrines, pilgrimages, processions (including Eucharistic processions), the Stations of the Cross (also known as the Way of the Cross), Holy Hours, Eucharistic Adoration, Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament, and the Rosary.

Personal prayer

Likewise, the great variety of Catholic spirituality enables individual Catholics to pray privately in many different ways. The fourth and last part of the Catechism thus summarized the Catholic's response to the mystery of faith: "This mystery, then, requires that the faithful believe in it, that they celebrate it, and that they live from it in a vital and personal relationship with the living and true God. This relationship is prayer."[50]

Particular Churches within the single Catholic Church

Unlike "families" or "federations" of Churches formed through the grant of mutual recognition by distinct ecclesial bodies, the Catholic Church considers itself a single Church ("one Body") composed of a multitude of local or particular Churches, each of which embodies the fullness of the one Catholic Church. The universal Church, however, is believed to be "a reality ontologically and temporally prior to every individual particular Church."[51]

However, the Catholic Church attaches great importance to the particular Churches within it, whose theological significance the Second Vatican Council highlighted. Two uses of the term particular Church are distinguished.

- Autonomous (sui iuris) particular Churches or Rites. See: Eastern Rite Catholic Churches

- Particular or local Churches (Dioceses and National Conferences of Bishops). See: Particular church

Relations with other Christian Churches

While the Catholic Church sees itself as the Church founded by Christ, it recognizes that many of the salvific elements of the Gospel are found in other Churches also. The Second Vatican Council document, Lumen Gentium, 8, says that the sole Church of Christ "subsists in", rather than simply "is" the Catholic Church. While affirming the doctrine of Extra Ecclesiam Nulla Salus, it states: "Nevertheless, many elements of sanctification and truth are found outside its visible confines. Since these are gifts belonging to the Church of Christ, they are forces impelling towards Catholic unity."

The Catholic Church has, since the Second Vatican Council, reached out to Christian bodies, seeking reconciliation to the greatest degree possible. Significant agreements have been achieved on Baptism, ministry and the Eucharist with Anglican theologians. With Lutheran bodies a similar agreement has been reached on the theology of justification. These landmark documents have brought closer fraternal ties with those Churches. However, recent developments, such as the ordination of women and accepting of couples living in homosexual relationships, present new obstacles to reconciliation with, in particular, Anglican, Lutheran and Reformed Churches.

Consequently, in recent years the Catholic Church has focused its efforts at reconciliation with the Orthodox Churches of the East, with which the theological differences are not as great. Relations with the Russian Orthodox Churches were strained in the 1990s over property issues in countries that were formerly Soviet-dominated, and these differences are not solved (most notably the parishes belonging to the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church), however fraternal relations with other Eastern churches continue to progress.

Hierarchical constitution of the Church

The Church is a hierarchical organization headed by the Pope, with ordained clergy divided into the orders of bishops, priests, and deacons.

Episcopate

The Bishops, who possess the fullness of Christian priesthood, are as a body (the College of Bishops) the successors of the Apostles [52] and are "constituted Pastors in the Church, to be the teachers of doctrine, the priests of sacred worship and the ministers of governance."[53]

The pope, cardinals, patriarchs, primates, archbishops and metropolitans are all bishops and members of the Catholic episcopate or college of bishops.

The Pope

What most obviously distinguishes the Catholic Church from other Christian bodies is the link between its members and the Pope. The Catechism of the Catholic Church, 882, quoting the Second Vatican Council’s document Lumen Gentium, states: "The Pope, Bishop of Rome and Peter’s successor, ‘is the perpetual and visible source and foundation of the unity both of the bishops and of the whole company of the faithful.’"[54]

The Pope is referred to as the Vicar of Christ and the Supreme Pontiff of the Universal Church. He may sometimes also use the less formal title of "Servant of the Servants of God". Applying to him the term "absolute" would, however, give a false impression: he is not free to issue decrees at whim. Instead, his charge forces on him awareness that he, even more than other bishops, is "tied", bound, by an obligation of strictest fidelity to the teaching transmitted down the centuries in increasingly developed form within the Catholic Church.

In certain limited and extraordinary circumstances, this papal primacy, which is referred to also as the Pope's Petrine authority or function, involves papal infallibility, i.e. the definitive character of the teaching on matters of faith and morals that he propounds solemnly as visible head of the Church. In any normal circumstances, exercise of this authority will involve previous consultation of all Catholic bishops (usually taking place in holy synods or an ecumenical council).

College of cardinals

Cardinals are appointed by the Pope, generally choosing bishops who head departments of the Roman Curia or important episcopal sees, Latin or Eastern, throughout the world. The cardinals make up the College of Cardinals which advises the pope, and those cardinals under the age of 80 elect a new pope during a papal vacancy.

The cardinalate is not an integral part of the theological structure of the Catholic Church, but largely an honorific distinction that has its origins in the 1059 assignation of the right of electing the Pope exclusively to the principal clergy of Rome and the bishops of the seven "suburbicarian" sees. Because of their resulting importance, the term "cardinal" (from Latin "cardo", meaning "hinge") was applied to them. In the twelfth century the practice of appointing ecclesiastics from outside Rome as cardinals began. Each cardinal is still assigned a church in Rome as his "titular church" or is linked with one of the suburbicarian dioceses.

Presbyterate (Priesthood)

Bishops are assisted by priests and deacons. Parishes, whether territorial or person-based, within a diocese are normally in the charge of a priest, known as the parish priest or the pastor.

Priests may perform many functions not directly connected with ordinary pastoral activity, such as study, research, teaching or office work. They may also be rectors of churches or chaplains of communities or special groups. Other titles or functions held by priests include those of Archimandrite, Canon Secular or Regular, Chancellor, Chorbishop, Confessor, Dean of a Cathedral Chapter, Hieromonk, Prebendary, Precentor, etc.

In the Latin Rite or particular Church, only celibate men, as a rule, are ordained as priests, while the Eastern Rites, again as a rule, also ordain married men. Among the Eastern particular Churches, the Ethiopic Catholic Church ordains only celibate clergy, while also having married priests who were ordained in the Orthodox Church, while other Eastern Catholic Churches, which do ordain married men, do not have married priests in certain countries, such as the United States of America. The Western or Latin Rite does sometimes, but very rarely, ordain married men, usually Protestant clergy who have become Catholics. All Rites of the Catholic Church maintain the ancient tradition that, after ordination, marriage is not allowed. Even a married priest whose wife dies may not then marry again.

Diaconate

Since the Second Vatican Council, the Latin Church again admits married men of mature age to ordination as Permanent deacons. "Deacons are ordained as a sacramental sign to the Church and to the world of Christ, who came 'to serve and not to be served.' The entire Church is called by Christ to serve, and the deacon, in virtue of his sacramental ordination and through his various ministries, is to be a servant in a servant-Church. As ministers of Word, deacons proclaim the Gospel, preach, and teach in the name of the Church. As ministers of Sacrament, deacons baptize, lead the faithful in prayer, witness marriages, and conduct wake and funeral services. As ministers of Charity, deacons are leaders in identifying the needs of others, then marshalling the Church's resources to meet those needs. Deacons are also dedicated to eliminating the injustices or inequities that cause such needs."[55]

Candidates for the Diaconate go through a Diaconate Formation program that is designed based on the contemporaneous needs of their Diocese but must meet minimum standards set by the Bishops Conference in their home country. Upon completion of their formation program and acceptance by their local Bishop, Candidates receive the Sacrament of Holy Orders through Ordination. Generally, following Ordination, a Deacon is assigned by his Bishop to a local Parish in which he will perform his ministry and serve the local church and community.

Laity

All baptized members of the Catholic Church are called faithful, truly equal in dignity and in the work to build the Church. All are called to share in Christ's priestly, prophetic, and royal office.[56] While a certain percentage of the faithful perform roles related to serving the ministerial priesthood (hierarchy) and giving eschatological witness (consecrated life), the great majority of the faithful perform a specific role of exercising the three offices of Christ by "engaging in temporal affairs and directing them according to God's will...to illuminate and order all temporal things."[57] These are the laity, whom John Paul II urged in Christifideles laici "to take an active, conscientious and responsible part in the mission of the Church," for they not only belong to the Church, but "are the Church." (Italics in the original)

Equipped with the common priesthood in baptism, these ordinary Catholics — e.g., mothers, farmers, businessmen, writers, politicians — are to take initiative in "discovering or inventing the means for permeating social, political, and economic realities with the demands of Christian doctrine and life."[58] They exercise the common, baptism-based priestly office by offering their prayer and works as spiritual sacrifices,[59] the prophetic office by their word and testimony of life in the ordinary circumstances of the world,[60] and the kingly office by self-mastery and conforming worldly institutions to the norms of justice.[61]

This theology of the laity, called a "characteristic mark" of Vatican II by Paul VI and John Paul II, was complemented, and in some cases influenced, by the rise of many lay ecclesial movements and structures in the 20th century: examples are Focolare, Neocatechumenal Way, Communion and Liberation, and the personal prelature of Opus Dei.

Consecrated life

Within the Catholic Church, the Consecrated Life refers to the following: the Religious Life, eremitical life, consecrated virginity, societies of consecrated life and secular institutes. All of these are ways of Christian living by those who have made the prescribed public profession and vow that is recognized in Church Law.[62] Those who have made their profession and vow are not, however, part of the Church hierarchy, unless they are also ordained priests. They commit themselves, for the love of God, to observe as binding certain counsels from the Christian Gospel. Most who feel called to following Christ in a more exacting way join what are called Religious Institutes,[63] often referred to in everyday life as religious orders or religious congregations, in which they follow a common rule under the leadership of a superior. They usually live in community, although some may for a shorter or longer time live the Religious Life as Hermits without ceasing to be a member of the Religious Institute.

Canons 603 and 604 give official recognition also to consecrated hermits and consecrated virgins who are not members of religious institutes (see below).

Catholic Church in society

Worldwide distribution

The number of Catholics in the world continues to increase, particularly in Africa and Asia, although the religion has lost much of its political influence in the "First World" (e.g. Europe, USA). The increase between 1978 and 2000 was 288 million. Protestant evangelicals have succeeded in making inroads into parts of Africa, but remain a small percentage of the population. In most industrialized countries, church attendance has decreased since the 19th century, though it remains higher than that of other "mainline" Churches.

According to Canon law, members are those who have been baptized in or, on making a profession of faith, have been received into the Catholic Church. They remain members, even if unfaithful to their obligations or even if excommunicated, unless they formally renounce membership by, for instance, joining another religion or denomination. However, in countries where a question on religion is included in the census, the number given in the Statistical Yearbook of the Church (see above) is that of the census returns; thus, for instance, in the case of New Zealand, where 27.5% of the population classified themselves in the 2001 census as being of no religion, the number of canonical Catholics is doubtless higher than the number appearing in the Statistical Yearbook of the Church. Furthermore, since Catholic population is the usual basis for assessing each diocese's contribution to national-level offices and services and the levy on each parish for diocesan initiatives, there is a temptation, not always resisted, for bishops and parish clergy in countries that do not have detailed census reports on religion to under-report the number of Catholics in their area.

Perspectives on the Catholic Church

Over the centuries, the Catholic Church has encountered criticisms for numerous reasons. (Some particular controversies are discussed in separate articles. See, for instance, on the charge of anti-Semitism, Relations between Catholicism and Judaism.) Pope John Paul II acknowledged publicly that certain members (including leadership) of the Catholic Church have sometimes been involved in questionable activities, and asked God to forgive the sins of its members, both in action and omission. See also: Criticism of the Catholic Church.

And at the same time, it has been seen by many people of different religions as a great force for good, as an "expert in humanity" and even as a model of management being seen by them as the oldest and biggest existing institution in the world. John Paul II was hailed upon his death as an outstanding world leader esteemed as having helped the world progress towards moral regeneration.

The number of criticisms and persecutions it has received through the centuries and his reading of sacred scripture inspired John Paul II to suggest that the term sign of contradiction is a "distinctive definition of Christ and of his Church."

Role of the Church in civilization

Church doctrine and science

Many enlightenment philosophers perceived the Church's doctrines as superstitious and hindering the progress of civilization. In the most famous instance, many criticized it for the 1633 trial of Galileo Galilei, in which the Church condemned his advancement of the heliocentric system of Catholic priest Nicolaus Copernicus, in favour of a geocentric system. Pope John Paul II publicly apologized for the Church's actions in that trial on 31 October 1992. An abstract of the acts of the process against Galileo is available at the Vatican Secret Archives, which reproduces part of it on its website.

Recently, the Church is criticized for its opposition to scientific research in fields such as embryonic stem cell research, which the Church teaches would cause the utilitarian destruction of a human being, or simply put, an act of murder. The Church argues that advances in medicine can come without the destruction of human embryos; for example, in the use of adult or umbilical stem cells in place of embryonic stem cells.

Historians of science including non-Catholics such as J.L. Heilbron,[64] Alistair Cameron Crombie, David Lindberg,[65] Edward Grant, Thomas Goldstein,[66] and Ted Davis have been revising the common notion — the product of black legends say some — that the Church has had a negative influence in the development of civilization. They argue that not only did the monks save and cultivate the remnants of ancient civilization during the barbarian invasions, but the Church promoted learning and science through its sponsorship of many universities which, under its leadership, grew rapidly in Europe in the 11th and 12th centuries. St. Thomas Aquinas, the Church's "model theologian," not only argued that reason is in harmony with faith, he even recognized that reason can contribute to understanding revelation, and so encouraged intellectual development. [67] The Church's priest-scientists, many of whom were Jesuits, were the leading lights in astronomy, genetics, geomagnetism, meteorology, seismology, and solar physics, becoming the "fathers" of these sciences. It is important to remark names of important churchmen such as the Augustinian abbot Gregor Mendel (pioneer in the study of genetics) and Belgian priest Georges Lemaître (the first to propose the Big Bang theory).

Cardinal John Henry Newman used to say in the nineteenth century that those who attack the Church can only point to the Galileo case, which to many historians does not prove the Church's opposition to science since many of the churchmen at that time were encouraged by the Church to continue their research.[68]

Church, art, and literature

While some critics accuse members of the Catholic Church of destroying the art of some of the colonized natives, several historians credit the Catholic Church for the brilliance and magnificence of Western art. They refer to the Church's fight against iconoclasm, a movement against visual representations of the divine, its insistence on building structures befitting worship, Augustine's repeated reference to Wisdom 11:20 (God "ordered all things by measure and number and weight") which led to the geometric constructions of Gothic architecture, the scholastics' coherent intellectual systems called the Summa Theologiae which influenced the intellectually consistent writings of Dante, its creation and sacramental theology which has developed a Catholic imagination influencing writers such as J. R. R. Tolkien[69] and William Shakespeare,[70] and lastly, the patronage of the Renaissance popes for the great works of Catholic artists such as Michelangelo, Raphael, Bernini, Borromini and Leonardo da Vinci.

Church and economic development

Francisco de Vitoria, a disciple of Thomas Aquinas and a Catholic thinker who studied the issue regarding the human rights of colonized natives, is recognized by the United Nations as a father of international law, and now also by historians of economics and democracy as a leading light for the West's democracy and rapid economic development.[71]

Joseph Schumpeter, an economist of the twentieth century, referring to the scholastics, wrote, "it is they who come nearer than does any other group to having been the ‘founders’ of scientific economics."[72] Other economists and historians, such as Raymond de Roover, Marjorie Grice-Hutchinson, and Alejandro Chafuen, have also made similar statements. Historian Paul Legutko of Stanford University said the Catholic Church is "at the center of the development of the values, ideas, science, laws, and institutions which constitute what we call Western civilization."[73]

Social justice, care-giving, and the hospital system

While it is criticized in many places, the Catholic Church also has contributed much to society through its Social Doctrine which has guided leaders to promote social justice and by setting up the hospital system in Medieval Europe, a system which was different from the merely reciprocal hospitality of the Greeks and family-based obligations of the Romans. These hospitals were established to cater to "particular social groups marginalized by poverty, sickness, and age," according to historian of hospitals, Guenter Risse.[74]

James Joseph Walsh wrote the following about the Catholic Church's contribution to the hospital system:

During the thirteenth century an immense number of [these] hospitals were built. The Italian cities were the leaders of the movement. Milan had no less than a dozen hospitals and Florence before the end of the Fourteenth century had some thirty hospitals. Some of these were very beautiful buildings. At Milan a portion of the general hospital was designed by Bramante and another part of it by Michelangelo. The Hospital of the innocents in Florence for foundlings was an architectural gem. The Hospital of Sienna, built in honor of St. Catherine, has been famous ever since. Everywhere throughout Europe this hospital movement spread. Virchow, the great German pathologist, in an article on hospitals, showed that every city of Germany of five thousand inhabitants had its hospital. He traced all of this hospital movement to Pope Innocent III, and though he was least papistically inclined, Virchow did not hesitate to give extremely high praise to this pontiff for all that he had accomplished for the benefit of children and suffering mankind.[75]

The beauty and efficiency of the Italian hospitals inspired even some who were otherwise critical of the Church. The German historian Ludwig von Pastor recounts the words of Martin Luther who, while journeying to Rome in the winter of 1510-1511, had occasion to visit some of these hospitals:

In Italy, he remarks, the hospitals are handsomely built, and admirably provided with excellent food and drink, careful attendants and learned physicians. The beds and bedding are clean, and the walls are covered with paintings. When a patient is brought in, his clothes are removed in the presence of a notary who makes a faithful inventory of them, and they are kept safely. A white smock is put on him and he is laid on a comfortable bed, with clean linen. Presently two doctors come to him, and the servants bring him food and drink in clean glasses, showing him all possible attention.[76]

The Catholic Church as opus proprium, says Benedict XVI in Deus Caritas Est, has conducted throughout the centuries from its very beginning and continues to conduct many charitable services — hospitals, schools, poverty alleviation programs, among others.

Controversial Catholic teachings

Throughout the centuries, the Church has had to respond to many criticisms, some of which are now considered outright heresies. Lately, criticisms tend to focus on a few issues, many of which deal with sex and gender themes. To these criticisms and controversies over traditional Church doctrine, the basic response of Benedict XVI, a renowned theologian, can be found in some statements before his election to the papacy: the Church is ecclesia sua, "his [God's] Church", and not the laboratory of theologians.[77]

Ordination reserved to men

The Church is convinced it is not free to change this practice, which is traced back to Jesus' choice of apostles, and to the practice of the apostles and their successors, and has declared the matter closed for discussion, the latest declaration being John Paul II's Ordinatio Sacerdotalis in 1994.

The Church claims that the reservation of the priesthood to men does not mean that the Catholic Church does not value women, since non-priests, men and women alike, can become saints just as easily as priests can.[78]

Clerical celibacy

The Catholic Church requires celibacy for Latin-Rite priests (with some minor exceptions) and all bishops. Voluntary celibacy has always been common in the Church and was generally the preferred state for priests and bishops. It is claimed that celibacy became mandatory for priests only in the eleventh century; others say, for instance: "(I)t may fairly be said that by the time of St. Leo the Great the law of celibacy was generally recognized in the West,"[79] that the eleventh-century regulations on this matter, as on simony, should clearly not be interpreted as meaning that either non-celibacy or simony were previously permitted,[80] and that the rule of total continence by the clergy (refraining from sexual relations with a wife married before ordination - thus, logically, not marrying after ordination) dates back to the origin of the Church.[81]

Pope John Paul II in Pastores Dabo Vobis stated that the "unchanging" essence of ordination "configures the priest to Jesus Christ the Head and Spouse of the Church." Thus, he said, "The Church, as the Spouse of Jesus Christ, wishes to be loved by the priest in the total and exclusive manner in which Jesus Christ her Head and Spouse loved her."

This teaching continues to be debated for a variety of reasons. First, many believe celibacy was not required of the apostles, though others think the apostles did leave their wives.[82] Second, this requirement excludes a great number of otherwise qualified men from the priesthood, qualifications which according to the defenders of celibacy should be determined not by merely human hermeneutics but by the hermeneutics of the divine will. Third, some say that resisting the natural sexual impulse in this way is unrealistic and harmful for a healthy life, a criticism which is countered by the faith in the power of grace and of man, made in the image of God who is Love. Sexual scandals among priests, the defenders say, are a breach of the Church's teaching, not a result of it, especially since only a small percentage of priests have been involved. Fourth, it is said that mandatory celibacy distances priests from this experience of life, compromising their moral authority in the pastoral sphere, although its defenders argue that the Church's moral authority is rather enhanced by a life of total self-giving in imitation of Christ, a practical application of Vatican II teaching that "man cannot fully find himself except through a sincere gift of himself."[83]

Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (better known now as Pope Benedict XVI) in Salt of the Earth also explained that this practice is based on Jesus' preaching on the eunuchs or celibates "for the sake of the kingdom of heaven" which links with God's decision in the Old Testament to confer the priesthood to a specific tribe, that of Levi, and who unlike the other tribes did not receive from God any land — an essential need for one's posterity as a wife and children are today — but had "God himself as its inheritance."[84]

Reforms of the Second Vatican Council

The Catholic Church undertook one of the most comprehensive reforms in its history during the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965) and the decade which followed. For changes in the liturgy, see Mass of Paul VI. The Church stressed more than before what it saw as positive rather than what it saw as negative in other Christian communities, other religions, and the aspirations of human beings in general. It encouraged the up-to-date renewal of religious life. And it empowered episcopal conferences to enact adaptations in disciplines such as abstinence from meat on Fridays.

Some Catholics, who have become known as traditionalist Catholics, rejected many of these changes, which they viewed as inconsistent with what the Church had always taught. Among the most controversial of changes was the adoption of a new rite of Mass, which traditionalist Catholics view as watered down, "protestantized", or even invalid.

Catholic teachings on human sexuality

The Catholic Church teaches that human life and human sexuality are both inseparable and sacred. Some criticize the Church's teaching on sexual and reproductive matters.[85] The Church requires members to eschew masturbation, fornication, pornography, prostitution, rape, homosexual practices,[86] and artificial contraception.[87] The procurement or assistance in abortion can carry the penalty of excommunication,[88] as a specific offence.

Some criticize the Church's teaching on fidelity, sexual abstinence and its opposition to promoting the use of condoms as a strategy to prevent the spread of HIV/AIDS, teen pregnancy, and STDs as counterproductive. However, the Church maintains that the promotion of abstinence is the only effective way to deal with the AIDS crisis.

Cardinal Javier Lozano Barragán, President of the Pontifical Council for Pastoral Assistance to Health Care Workers, has stated that Pope Benedict XVI asked his department to study the issue as part of a broad look at several questions of bioethics.[89] However, the president of the Pontifical Council for the Family, Cardinal Alfonso López Trujillo, in an interview reported by Catholic News Agency on May 4, 2006, said that the Church "maintains unmodified the teaching on condoms", and added that the Pope had "not ordered any studies about modifying the prohibition on condom use."[90]

Sexual abuse scandals

In 2002, a major scandal erupted in the U.S. Catholic Church when a wealth of allegations of priests sexually abusing children surfaced. Adding to the furor were revelations that the Church was aware of some of the abusive priests, and simply shuffled them from congregation to congregation instead of taking action. The scandal led to the resignation of Cardinal Bernard Law from the Boston archdiocese. It also led to a common perception — 64% of those polled, in one survey — that Catholic priests "frequently abused children," while the data show that only 1.5-1.8% of Catholic priests are accused of child sexual abuse.[91]

The Catholic News Service reported:

About 4 percent of U.S. priests ministering from 1950 to 2002 were accused of sex abuse with a minor, according to the first comprehensive national study of the issue.

The study said that 4,392 clergymen—almost all priests—were accused of abusing 10,667 people, with 75 percent of the incidents taking place between 1960 and 1984.

During the same time frame there were 109,694 priests, it said. Sex-abuse related costs totaled $573 million, with $219 million covered by insurance companies, said the study done by the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York.

The study listed the main characteristics of the sex abuse incidents reported. These included:

-- An overwhelming majority of the victims, 81 percent, were males. The most vulnerable were boys aged 11 to 14, representing more than 40 percent of the victims. This goes against the trend in the general U.S. society where the main problem is men abusing girls.[92]

In Ireland, a number of high-profile cases of sexual abuse of children by Catholic priests and brothers, such as that of Andrew Madden, have contributed to a significant decline in influence of the Church in recent years.

Since 2001, the adjudication of charges of sexual abuse by clergy is no longer within the competence of the local bishop, but is reserved to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith in Rome, in accord with Pope John Paul II's Apostolic Letter Sacramentorum sanctitatis tutela and its accompanying norms (both documents in Latin). Under the Church's 1983 Code of Canon Law clerical sexual abuse against a minor can be punished with dismissal from the clerical state ("laicization").[93]

See also

- Other articles on the Catholic Church

- Catholic Church by country

- History of the Roman Catholic Church

- Catholic

- Catholicism

- Christianity

- Christian apologetics

- Primacy of the Roman Pontiff

- Catholic church hierarchy

- Canon law (Catholic Church)

- Lists of Roman Catholics

- Traditionalist Catholic

- Anti-Catholicism

- Criticism of the Catholic Church

- Catholicism and Freemasonry

- Forgiveness

- Jesus

- Latin language

- Pro-life

- Roman Catholic calendar of saints

- List of Catholic converts

- List of canonizations

Footnotes

- ^ "Major Branches of Religions". adherents.com. Retrieved 2006-09-14.

- ^ Central Statistics Office (2006). Statistical Yearbook of the Church 2004. Libreria Editrice Vaticana. ISBN 8820978172.

- ^ Central Statistics Office (2005). Annuario Pontificio (Pontifical Yearbook). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. ISBN 8820976781.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Irish Hierarchy (1985). "Love is for Life: Pastoral Letter of the Irish Bishops (#46)". Catholic Culture: Document Library. Veritas Publications. Retrieved 2006-09-14. – Uses "the Love". cf. Decretum Gelasianum.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church 748-810

- ^ Instances of the Catholic Church: "Joint International Commission between representatives of the Catholic Church and the Lutheran World Federation". Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity. Vatican. Retrieved 2006-09-14.; Lutheran World Federation and the Catholic Church (1999). "Official Common Statement". Vatican. Retrieved 2006-09-14.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Pope John Paul II, Mar Khanania Dinkha IV (1994). "Common Christological Declaration between the Catholic Church and the Assyrian Church of the East". Vatican. Retrieved 2006-09-14.{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Instances of the Roman Catholic Church: Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity (2003). "Final Communiqué of the Joint Group between the Roman Catholic Church and the World Council of Churches". Vatican. Retrieved 2006-09-14.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity (2005). "Anglican – Roman Catholic International Commission (ARCIC)". Vatican. Retrieved 2006-09-14.{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Commission for Religious Relations with the Jews (1982). "Notes on the Correct Way to Present the Jews and Judaism in Preaching and Catechesis in the Roman Catholic Church". Vatican. Retrieved 2006-09-14.{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Pope Pius XI (1929). "Divini Illius Magistri". Vatican. Retrieved 2006-09-14.{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Pope Pius XII (1950). "Humani Generis". Vatican. Retrieved 2006-09-14.{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Roman Catholic". Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2006-09-14.

- ^ St. Augustine (397). "Chapter 4: Proofs of the Catholic Faith". Against the Epistle of Manichaeus Called Fundamental.

- ^ a b Pope Paul VI (1964). "Lumen Gentium (Dogmatic Constitution on the Church), 8". Vatican. Retrieved 2006-09-14.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Matthew 16:18

- ^ Ignatius of Antioch. "Letter to the Smyrnaeans". para. 8.

- ^ "The Authority of the Pope: Part I". Catholic Answers.

- ^ 2 Corinthians 11:13–15; 2 Peter 2:1–17; 2 John 7–11; Jude 4–13

- ^ Acts 15:1–2

- ^ Halsall, Paul (1997). "Theodosian Code XVI.i.2". Medieval Sourcebook: Banning of Other Religions. Fordham University. Retrieved 2006-09-19.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ MacCulloch, Diarmaid (2003). The Reformation: A History. Penguin Group. p. 412. ISBN 9780713993707.; MacCulloch adds "admittedly, that might not have been much consolation to those burned at the stake."; see also Kamen, Henry (1999). The Spanish Inquisition: A Historical Revision. Yale University Press. pp. 59–60, 189–90, 203, 301. ISBN 0300078803.

- ^ Pope Pius XII. "Divino Afflante Spiritu". Vatican. para. 16.

- ^ Romans 1:20

- ^ Matthew 11:27

- ^ Romans 5:12

- ^ Ephesians 1:22–23; cf. Romans 12:4–5

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 77-78

- ^ Matthew 28:20

- ^ John 14:16–17; John 14:26

- ^ Matthew 18:18; Luke 10:16

- ^ Matthew 18:17

- ^ 1 Timothy 3:15

- ^ 1 Corinthians 11:2; 2 Thess 2:15; 1 Thess 2:13; 2 Thess 3:6; 2 Timothy 2:2

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 85

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 773, 775

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2007

- ^ Romans 3:22

- ^ Romans 6:3–4

- ^ Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity. "Response of the Catholic Church to the Joint Declaration of the Catholic Church and the Lutheran World Federation on the Doctrine of Justification, 2–3". Vatican. Retrieved 2006-09-15.

- ^ James 2:26

- ^ James 2:24

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1987–2016

- ^ Pope Paul VI (1964). "Lumen Gentium (Dogmatic Constitution on the Church), 14". Vatican. Retrieved 2006-09-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Pope Paul VI (1964). "Lumen Gentium (Dogmatic Constitution on the Church), 11". Vatican. Retrieved 2006-09-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Matthew 5:44

- ^ Koch, Carl (1994). The Catholic Church. Saint Mary's Press. ISBN 0884892980.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Aquinas, Thomas. "Of War (Four Articles), Q. 40". The Summa Theologica (Second Part of Second Part). Benzinger Brothers. Retrieved 2006-09-15.

- ^ Pope John Paul II (1995). "Evangelium Vitae". Vatican. Retrieved 2006-09-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Pope John Paul II (20 February 1980). "General Audience". Vatican. Retrieved 2006-09-15.

- ^ Genesis 1:31

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1015

- ^ Pope John Paul II (29 October 1980). "General Audience, 6". L'Osservatore Romano. Retrieved 2006-09-15.

- ^ Pope Paul VI (1963). "Sacrosanctum Concilium, 2". Vatican. Retrieved 2006-09-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Catechism of the Catholic Church 1068-69 - ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church 2558

- ^ Joseph Card. Ratzinger, Alberto Bovone (1992). "Letter to the Bishops of the Catholic Church on Some Aspects of the Church Understood as Communion, 9". Vatican. Retrieved 2006-09-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Canon 42". Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches.

- ^ "Canon 375". 1983 Code of Canon Law. Vatican.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church 882

- ^ Committee on the Diaconate. "Frequently Asked Questions About Deacons". United States Conference of Catholic Bishops.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 871-2

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 898

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 899

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 901

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 905

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 908-9

- ^ "Canons 573-746". Code of Canon Law. Vatican.

- ^ "Canons 573–602, 605–709". Code of Canon Law. Vatican.

- ^ "J.L. Heilbron". London Review of Books. Retrieved 2006-09-15.

- ^ Lindberg, David (2003). When Science and Christianity Meet. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226482146.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Goldstein, Thomas (1995). Dawn of Modern Science: From the Ancient Greeks to the Renaissance. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0306806371.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Pope John Paul II (1998). "Fides et Ratio (Faith and Reason), IV". Retrieved 2006-09-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization". Catholic Education Resource Center. 2005.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Boffetti, Jason (2001). "Tolkien's Catholic Imagination". Crisis Magazine. Morley Publishing Group.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Voss, Paul J. (2002). "Assurances of faith: How Catholic Was Shakespeare? How Catholic Are His Plays?". Crisis Magazine. Morley Publishing Group.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ de Torre, Fr. Joseph M. (1997). "A Philosophical and Historical Analysis of Modern Democracy, Equality, and Freedom Under the Influence of Christianity". Catholic Education Resource Center.

- ^ Schumpeter, Joseph (1954). History of Economic Analysis. London: Allen & Unwin.

- ^ "Review of How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization by Thomas Woods, Jr". National Review Book Service. Retrieved 2006-09-16.

- ^ Risse, Guenter B (1999). Mending Bodies, Saving Souls: A History of Hospitals. Oxford University Press. p. 59. ISBN 0195055233.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Walsh, James Joseph (1924). The world's debt to the Catholic Church. The Stratford Company. p. 244.

- ^ von Pastor, Ludwig (1891). The History of the Popes from the Close of the Middle Ages (Volume V). B. Herder. p. 65. cf. Luther, Martin. (1967). Luther's Works, American Edition, 55 vols. Helmut T. Lehmann, Theodore G. Tappert, editors, Concordia Publishing House and Fortress Press, Table Talk, vol. 54, p.296, No. 3930, ( recorded by Anthony Lauterbach, August 1, 1538 ). ISBN 0800603540

- ^ Allen, John L. (2005). The Rise of Benedict XVI. Doubleday Publishing. ISBN 0385513208.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Pope Benedict XVI (1971). Two Say Why: Why I am still a Christian. Franciscan Herald Press. ISBN 0855322896.{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (1976). "Inter Insigniores Declaration on the Admission of Women to the Ministerial Priesthood".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Celibacy of the Clergy". Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2006-09-16.

- ^ "Gregory VII: Simony and Celibacy 1074". Medieval Sourcebook.

- ^ Ignace de la Potterie (1993). "The Biblical Foundation of Priestly Celibacy". Vatican.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Fr. Thomas McGovern (1998). "Chapter 1: Celibacy: A Historical Perspective". Priestly Celibacy Today. - ^ cf. Luke 18:28–30

- ^ Pope Paul VI (1965). "Gaudium et Spes". Vatican. Retrieved 2006-09-16.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Num 1:48–53

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2331-2400

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2351-2357

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2370

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2272

- ^ Dickey, Christopher (2006). "Catholics and Condoms". Newsweek. MSNBC. Retrieved 2006-09-16.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Church 'will not budge one inch' on issue of condom use, says Cardinal Lopez Trujillo". Catholic News Agency. 2006. Retrieved 2006-09-16.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights (2004). "Sexual Abuse in Social Context: Catholic Clergy and Other Professionals". Retrieved 2006-09-16.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Bono, Agostino. "John Jay Study Reveals Extent of Abuse Problem". Catholic News Service.

- ^ "Canon 1395". Code of Canon Law. Vatican.

References and readings

- "Catechism of the Catholic Church". Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 1993.

- "Compendium of the Catechism of the Catholic Church". Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2005.

- "Annuarium Statisticum Ecclesiae (Annual Church Statistics)". EWTN. 2004. Retrieved 2006-09-14.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Carroll, Warren (2004). History of Christendom. Christendom Press. ISBN 0931888212.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) 4 Volumes. - Central Statistics Office (2006). Annuario Pontificio. Libreria Editrice Vaticana. ISBN 8820978067.

- Crocker, III, H. W. (2001). Triumph: The Power and the Glory of the Catholic Church: A 2,000-Year History. Prima Lifestyles. ISBN 0761529241.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Herbermann, Charles G.; et al. (1913). "Catholic Encyclopedia". Encyclopedia Press.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Hughes, Philip (1947). A History of the Church: The World in Which the Church Was Founded. Sheed & Ward. ISBN 0722079818.

- Miller, Adam S. (1997, 2006). The Roman Catholic Church: A Divine Institution or a Human Invention?. Tower of David Publications.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Woods, Jr., Thomas (2005). How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization. Regnery Publishing. ISBN 0895260387.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

External links

- Vatican: the Holy See the official website of the Vatican

- Catholic Hierarchy Information on Catholic bishops and dioceses

- The Cardinals of the Holy Roman Church Information on the Cardinals of the Catholic Church

- Global Catholic Statistics: 1905 and Today by Albert J. Fritsch, SJ, PhD

- Catholic Answers One of the largest lay-run apostolates of Catholic apologetics and evangelization

- Mary Foundation Free CDs summarizing basic Roman Cathoic teaching on the Mass, Mary, etc.

- American Catholic Catholic Church Questions - FAQs about Catholicism

- Catholic Wiki - An orthodox wiki site dedicated to building up a plethora of information on the Catholic Church.