Winnie-the-Pooh

| Winnie-the-Pooh | |

|---|---|

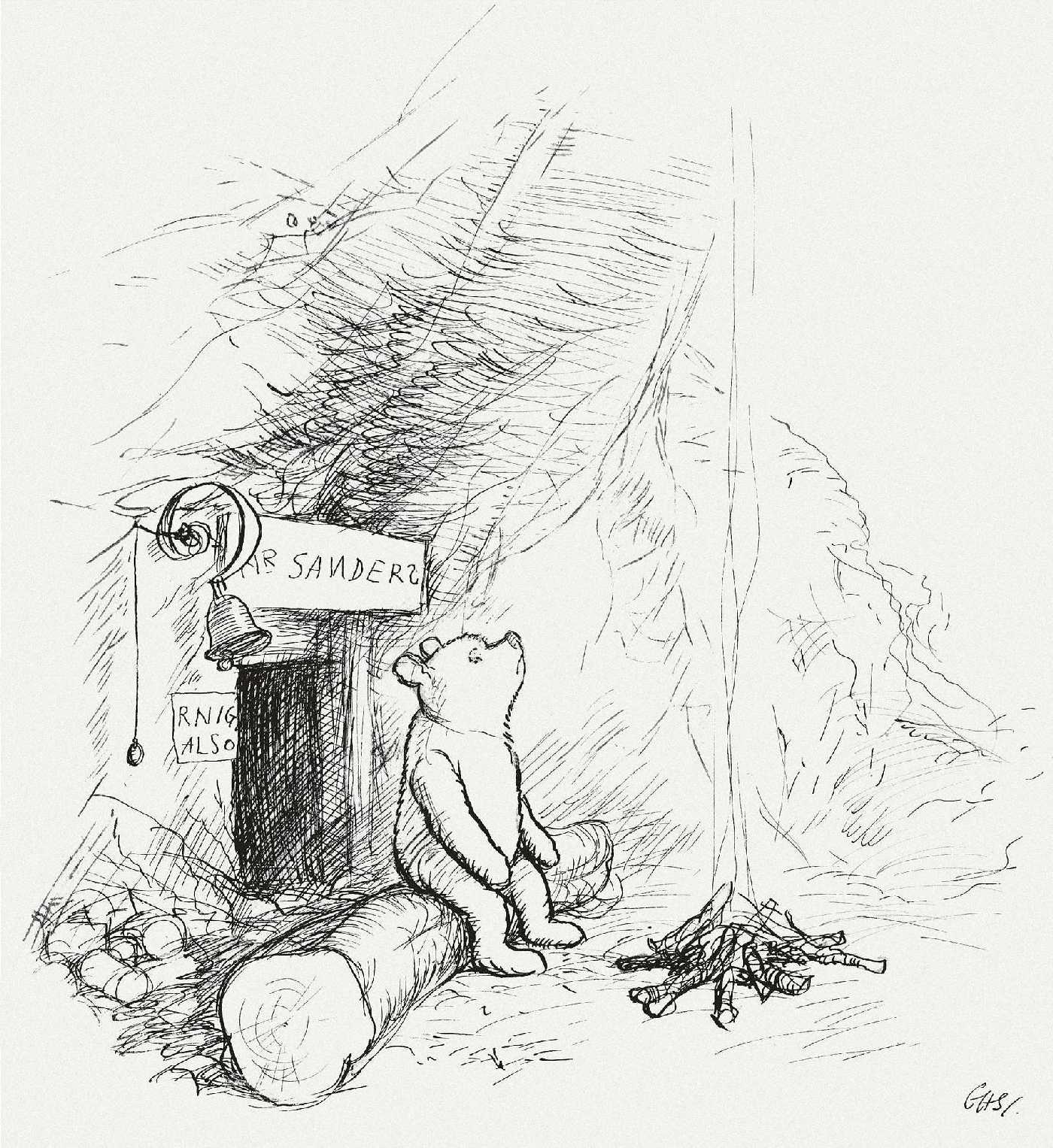

Pooh in an illustration by E. H. Shepard | |

| First appearance | When We Were Very Young (1924) (As Edward Bear) Winnie-the-Pooh (As Winnie-the-Pooh) |

| Created by | A. A. Milne |

| Voiced by |

|

| In-universe information | |

| Nickname | Pooh Bear Pooh |

| Species | Bear |

| Gender | Male[citation needed] |

Winnie-the-Pooh, also called Pooh Bear, is a fictional anthropomorphic teddy bear created by English author A. A. Milne.

The first collection of stories about the character was the book Winnie-the-Pooh (1926), and this was followed by The House at Pooh Corner (1928). Milne also included a poem about the bear in the children's verse book When We Were Very Young (1924) and many more in Now We Are Six (1927). All four volumes were illustrated by E. H. Shepard.

The Pooh stories have been translated into many languages, including Alexander Lenard's Latin translation, Winnie ille Pu, which was first published in 1958, and, in 1960, became the only Latin book ever to have been featured on The New York Times Best Seller list.[1]

Hyphens in the character's name were omitted by Disney when the company adapted the Pooh stories into a series of features that would eventually become one of its most successful franchises.

In popular film adaptations, Pooh has been voiced by actors Sterling Holloway, Hal Smith, and Jim Cummings in English, and Yevgeny Leonov in Russian.

History

Origin

A. A. Milne named the character Winnie-the-Pooh after a teddy bear owned by his son, Christopher Robin Milne, on whom the character Christopher Robin was based. The rest of Christopher Robin Milne's toys – Piglet, Eeyore, Kanga, Roo, and Tigger – were incorporated into Milne's stories.[2][3] Two more characters, Owl and Rabbit, were created by Milne's imagination, while Gopher was added to the Disney version. Christopher Robin's toy bear is on display at the Main Branch of the New York Public Library in New York City.[4]

Christopher Milne had named his toy bear after Winnie, a Canadian black bear he often saw at London Zoo, and "Pooh", a swan they had met while on holiday. The bear cub was purchased from a hunter for $20 by Canadian Lieutenant Harry Colebourn in White River, Ontario, Canada, while en route to England during the First World War.[5] He named the bear "Winnie" after his adopted hometown in Winnipeg, Manitoba. "Winnie" was surreptitiously brought to England with her owner, and gained unofficial recognition as The Fort Garry Horse regimental mascot. Colebourn left Winnie at the London Zoo while he and his unit were in France; after the war she was officially donated to the zoo, as she had become a much-loved attraction there.[6] Pooh the swan appears as a character in its own right in When We Were Very Young.

In the first chapter of Winnie-the-Pooh, Milne offers this explanation of why Winnie-the-Pooh is often called simply "Pooh":

But his arms were so stiff ... they stayed up straight in the air for more than a week, and whenever a fly came and settled on his nose he had to blow it off. And I think – but I am not sure – that that is why he is always called Pooh.

The American writer William Safire surmised that the Milnes' invention of the name "Winnie the Pooh" may have also been influenced by the haughty character Pooh-Bah in Gilbert and Sullivan's The Mikado (1885).[7]

Ashdown Forest: the setting for the stories

The Winnie-the-Pooh stories are set in Ashdown Forest, East Sussex, England. The forest is an area of tranquil open heathland on the highest sandy ridges of the High Weald Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty situated 30 miles (50 km) south-east of London. In 1925 Milne, a Londoner, bought a country home a mile to the north of the forest at Cotchford Farm, near Hartfield. According to Christopher Milne, while his father continued to live in London "...the four of us – he, his wife, his son and his son's nanny – would pile into a large blue, chauffeur-driven Fiat and travel down every Saturday morning and back again every Monday afternoon. And we would spend a whole glorious month there in the spring and two months in the summer."[8] From the front lawn the family had a view across a meadow to a line of alders that fringed the River Medway, beyond which the ground rose through more trees until finally "above them, in the faraway distance, crowning the view, was a bare hilltop. In the centre of this hilltop was a clump of pines." Most of his father's visits to the forest at that time were, he noted, family expeditions on foot "to make yet another attempt to count the pine trees on Gill's Lap or to search for the marsh gentian". Christopher added that, inspired by Ashdown Forest, his father had made it "the setting for two of his books, finishing the second little over three years after his arrival".[9]

Many locations in the stories can be associated with real places in and around the forest. As Christopher Milne wrote in his autobiography: "Pooh’s forest and Ashdown Forest are identical". For example, the fictional "Hundred Acre Wood" was in reality Five Hundred Acre Wood; Galleon's Leap was inspired by the prominent hilltop of Gill's Lap, while a clump of trees just north of Gill's Lap became Christopher Robin's The Enchanted Place because no-one had ever been able to count whether there were 63 or 64 trees in the circle.[10]

The landscapes depicted in E. H. Shepard's illustrations for the Winnie-the-Pooh books were directly inspired by the distinctive landscape of Ashdown Forest, with its high, open heathlands of heather, gorse, bracken and silver birch punctuated by hilltop clumps of pine trees. Many of Shepard's illustrations can be matched to actual views, allowing for a degree of artistic licence. Shepard's sketches of pine trees and other forest scenes are held at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.[11]

The game of Poohsticks was originally played by Christopher Milne on a footbridge across a tributary of the River Medway in Posingford Wood, close to Cotchford Farm. The wooden bridge is now a tourist attraction, and it has become traditional to play the game there using sticks gathered in the nearby woodland.[12][13] When the footbridge recently had to be replaced, the engineer designed a new structure based closely on the drawings of the bridge by Shepard in the books, which were somewhat different from the original structure.

First publication

Christopher Robin's teddy bear, Edward, made his character début in A. A. Milne's poem, "Teddy Bear", in the edition of 13 February 1924 of Punch, and the same poem was published in Milne's book of children's verse When We Were Very Young (6 November 1924).[14] Winnie-the-Pooh first appeared by name on 24 December 1925, in a Christmas story commissioned and published by the London newspaper The Evening News. It was illustrated by J. H. Dowd.[15]

The first collection of Pooh stories appeared in the book Winnie-the-Pooh. The Evening News Christmas story reappeared as the first chapter of the book. At the beginning, it explained that Pooh was in fact Christopher Robin's Edward Bear, who had been renamed by the boy. He was renamed after an American black bear at London Zoo called Winnie who got her name from the fact that her owner had come from Winnipeg, Canada. The book was published in October 1926 by the publisher of Milne's earlier children's work, Methuen, in England, E. P. Dutton in the United States, and McClelland & Stewart in Canada.[16]

Character

In the Milne books, Pooh is naive and slow-witted, but he is also friendly, thoughtful and steadfast. Although he and his friends agree that he "has no Brain", Pooh is occasionally acknowledged to have a clever idea, usually driven by common sense. These include riding in Christopher Robin's umbrella to rescue Piglet from a flood, discovering "the North Pole" by picking it up to help fish Roo out of the river, inventing the game of Poohsticks, and getting Eeyore out of the river by dropping a large rock on one side of him to wash him towards the bank.

Pooh is also a talented poet and the stories are frequently punctuated by his poems and "hums". Although he is humble about his slow-wittedness, he is comfortable with his creative gifts. When Owl's house blows down in a windstorm, trapping Pooh, Piglet and Owl inside, Pooh encourages Piglet (the only one small enough to do so) to escape and rescue them all by promising that "a respectful Pooh song" will be written about Piglet's feat. Later, Pooh muses about the creative process as he composes the song.

Pooh is very fond of food, particularly "hunny", but also condensed milk and other items. When he visits friends, his desire to be offered a snack is in conflict with the impoliteness of asking too directly. Though intent on giving Eeyore a pot of honey for his birthday, Pooh could not resist eating it on his way to deliver the present and so instead gives Eeyore "a useful pot to put things in". When he and Piglet are lost in the forest during Rabbit's attempt to "unbounce" Tigger, Pooh finds his way home by following the "call" of the honeypots from his house. Pooh makes it a habit to have "a little something" around 11:00 in the morning. As the clock in his house "stopped at five minutes to eleven some weeks ago," any time can be Pooh's snack time.

Pooh is very social. After Christopher Robin, his closest friend is Piglet, and he most often chooses to spend his time with one or both of them. But he also habitually visits the other animals, often looking for a snack or an audience for his poetry as much as for companionship. His kind-heartedness means he goes out of his way to be friendly to Eeyore, visiting him and bringing him a birthday present and building him a house, despite receiving mostly disdain from Eeyore in return.

Sequel

An authorised sequel Return to the Hundred Acre Wood was published on 5 October 2009. The author, David Benedictus, has developed, but not changed, Milne's characterisations. The illustrations, by Mark Burgess, are in the style of Shepard.[17]

Another authorised sequel, Winnie-the-Pooh: The Best Bear in All the World, was published by Egmont in 2016. The sequel consists of four short stories by four leading children's authors, Kate Saunders, Brian Sibley, Paul Bright and Jeanne Willis. Illustrations are by Mark Burgess.[18] The Best Bear in All The World sees the introduction of a new character, a Penguin, which was inspired by a long-lost photograph of Milne and his son Christopher with a toy penguin.[19] A further special story, Winnie-the-Pooh Meets the Queen, was published in 2016 to mark the 90th anniversary of Milne's creation and the 90th birthday of Elizabeth II. It sees Winnie the Pooh meet the Queen at Buckingham Palace.[20]

Stephen Slesinger

On 6 January 1930, Stephen Slesinger purchased U.S. and Canadian merchandising, television, recording and other trade rights to the "Winnie-the-Pooh" works from Milne for a $1,000 advance and 66% of Slesinger's income, creating the modern licensing industry. By November 1931, Pooh was a $50 million-a-year business.[21] Slesinger marketed Pooh and his friends for more than 30 years, creating the first Pooh doll, record, board game, puzzle, U.S. radio broadcast (NBC), animation and motion picture film.[22]

Red shirt Pooh

The first time Pooh and his friends appeared in colour was 1932, when he was drawn by Slesinger in his now-familiar red shirt and featured on an RCA Victor picture record. Parker Brothers introduced A. A. Milne's Winnie-the-Pooh Game in 1933, again with Pooh in his red shirt. In the 1940s, Agnes Brush created the first plush dolls with Pooh in his red shirt. Shepard had drawn Pooh with a shirt as early as the first Winnie-The-Pooh book, which was subsequently coloured red in later coloured editions.

Disney ownership era (1966–present)

After Slesinger's death in 1953, his wife, Shirley Slesinger Lasswell, continued developing the character herself. In 1961, she licensed rights to Walt Disney Productions in exchange for royalties in the first of two agreements between Stephen Slesinger, Inc. and Disney.[23] The same year, A. A. Milne's widow, Daphne Milne, also licensed certain rights, including motion picture rights, to Disney.

Since 1966, Disney has released numerous animated productions starring Winnie the Pooh and related characters. These have included theatrical featurettes, television series, and direct-to-video films, as well as the theatrical feature-length films The Tigger Movie, Piglet's Big Movie, Pooh's Heffalump Movie, and Winnie the Pooh.

Merchandising revenue dispute

Pooh videos, soft toys and other merchandise generate substantial annual revenues for Disney. The size of Pooh stuffed toys ranges from Beanie and miniature to human-sized. In addition to the stylised Disney Pooh, Disney markets Classic Pooh merchandise which more closely resembles E.H. Shepard's illustrations.

In 1991, Stephen Slesinger, Inc. filed a lawsuit against Disney which alleged that Disney had breached their 1983 agreement by again failing to accurately report revenue from Winnie the Pooh sales. Under this agreement, Disney was to retain approximately 98% of gross worldwide revenues while the remaining 2% was to be paid to Slesinger. In addition, the suit alleged that Disney had failed to pay required royalties on all commercial exploitation of the product name.[24] Though the Disney corporation was sanctioned by a judge for destroying forty boxes of evidential documents,[25] the suit was later terminated by another judge when it was discovered that Slesinger's investigator had rummaged through Disney's garbage to retrieve the discarded evidence.[26] Slesinger appealed the termination and, on 26 September 2007, a three-judge panel upheld the lawsuit dismissal.[27]

After the Copyright Term Extension Act of 1998, Clare Milne, Christopher Milne's daughter, attempted to terminate any future U.S. copyrights for Stephen Slesinger, Inc.[28] After a series of legal hearings, Judge Florence-Marie Cooper of the U.S. District Court in California found in favour of Stephen Slesinger, Inc., as did the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. On 26 June 2006, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear the case, sustaining the ruling and ensuring the defeat of the suit.[29]

On 19 February 2007 Disney lost a court case in Los Angeles which ruled their "misguided claims" to dispute the licensing agreements with Slesinger, Inc. were unjustified,[30] but a federal ruling of 28 September 2009, again from Judge Florence-Marie Cooper, determined that the Slesinger family had granted all trademarks and copyrights to Disney, although Disney must pay royalties for all future use of the characters. Both parties have expressed satisfaction with the outcome.[31][32]

Adaptations

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2018) |

Theatre

- Winnie-the-Pooh at the Guild Theater, Sue Hastings Marionettes, 1931[33]

- Winnie-the-Pooh, a play in three acts, dramatized by Kristin Sergel, Dramatic Publishing Company, 1957

- Winnie-the-Pooh, a musical comedy in two acts, lyrics by A. A. Milne and Kristin Sergel, music by Allan Jay Friedman, book by Kristin Sergel, Dramatic Publishing Company, 1964

- A Winnie-the-Pooh Christmas Tail, In Which Winnie-the-Pooh and His Friends Help Eeyore Have a Very Merry Christmas (Or a Very Happy Birthday), book, music and lyrics by James W. Rogers, Dramatic Publishing Company, 1977

- "Bother! The Brain of Pooh", Peter Dennis, 1986

- Winnie-the-Pooh, small cast musical version, dramatized by le Clanché du Rand, music by Allan Jay Friedman, lyrics by A. A. Milne and Kristin Sergel, additional lyrics by le Clanché du Rand, Dramatic Publishing Company, 1992

Audio

Selected Pooh stories read by Maurice Evans released on vinyl LP:

- Winnie-the-Pooh (consisting of three tracks: "Introducing Winnie-the-Pooh and Christopher Robin"; Pooh Goes Visiting and Gets into a Tight Place"; "Pooh and Piglet Go Hunting and Nearly Catch a Woozle") 1956

- More Winnie-the-Pooh (consisting of three tracks: "Eeyore Loses a Tail"; "Piglet Meets a Heffalump"; "Eeyore Has a Birthday")

In 1951, RCA Records released four stories of Winnie-the-Pooh, narrated by Jimmy Stewart and featuring the voices of Cecil Roy as Pooh, Betty Jane Tyler as Kanga, Merrill Joels as Eeyore, and Arnold Stang as Rabbit.

In 1960 HMV recorded a dramatised version with songs (music by Harold Fraser-Simson) of two episodes from The House at Pooh Corner (Chapters 2 and 8), starring Ian Carmichael as Pooh, Denise Bryer as Christopher Robin (who also narrated), Hugh Lloyd as Tigger, Penny Morrell as Piglet, and Terry Norris as Eeyore. This was released on a 45 rpm EP.[34]

In the 1970s and 1980s, Carol Channing recorded Winnie the Pooh, The House at Pooh Corner and The Winnie the Pooh Songbook, with music by Don Heckman. These were released on vinyl LP and audio cassette by Caedmon Records.

Unabridged recordings read by Peter Dennis of the four Pooh books:

- When We Were Very Young

- Winnie-the-Pooh

- Now We Are Six

- The House at Pooh Corner

In 1979 a double audio cassette set of Winnie the Pooh was produced featuring British actor Lionel Jeffries reading all characters in the stories. This was followed in 1981 by an audio cassette set of stories from The House at Pooh Corner also read by Lionel Jeffries.[35]

In the 1990s, the stories were dramatised for audio by David Benedictus, with music composed, directed and played by John Gould. They were performed by a cast that included Stephen Fry as Winnie-the-Pooh, Jane Horrocks as Piglet, Geoffrey Palmer as Eeyore and Judi Dench as Kanga.[36]

Radio

- Winnie-the-Pooh was broadcast by Donald Calthrop over all BBC stations on Christmas Day, 1925.[15]

- Pooh made his U.S. radio debut on 10 November 1932, when he was broadcast to 40,000 schools by The American School of the Air, the educational division of the Columbia Broadcasting System.[37]

Film

- 2017: Goodbye Christopher Robin, a drama film exploring the creation of Winnie-the-Pooh by A.A. Milne.

Soviet adaptation

In the Soviet Union, three Winnie-the-Pooh, (transcribed in Russian as "Vinni Pukh") (Russian language: Винни-Пух) stories were made into a celebrated trilogy[38] of short films by Soyuzmultfilm (directed by Fyodor Khitruk) from 1969 to 1972, after being granted permission by Disney to make their own adaptation in a gesture of Cold War détente.[39]

- Винни-Пух (Winnie-the-Pooh, 1969) – based on chapter 1

- Винни-Пух идёт в гости (Winnie-the-Pooh Pays a Visit, 1971) – based on chapter 2

- Винни-Пух и день забот (Winnie the Pooh and the Blustery Day, 1972) – based on chapters 4 and 6.

Films use Boris Zakhoder's translation of the book. Pooh was voiced by Yevgeny Leonov. Unlike the Disney adaptations, the animators did not base their depictions of the characters on Shepard's illustrations, creating a different look. The Soviet adaptations make extensive use of Milne's original text and often bring out aspects of Milne's characters' personalities not used in the Disney adaptations.

Television

- 1958-1960: Shirley Temple's Storybook on NBC: Winnie-the-Pooh' A marioneets version of Winnie The Pooh, designed, made and operated by Bil And Cora Baird.

Pooh himself is voiced by Franz Fazakas.

- During the 1970s the BBC children's television show Jackanory serialised the two books, which were read by Willie Rushton.[40]

Disney adaptations

Theatrical shorts

- 1966: Winnie the Pooh and the Honey Tree

- 1968: Winnie the Pooh and the Blustery Day

- 1974: Winnie the Pooh and Tigger Too

- 1981: Winnie the Pooh Discovers the Seasons

- 1983: Winnie the Pooh and a Day for Eeyore

Theatrical feature films

- 1977: The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh (compilation of Honey Tree, Blustery Day, and Tigger Too)

- 2000: The Tigger Movie

- 2003: Piglet's Big Movie

- 2005: Pooh's Heffalump Movie

- 2011: Winnie the Pooh

- 2018: Christopher Robin[41][42]

Television shows

- Welcome to Pooh Corner (*) (Disney Channel, 1983–1986)

- The New Adventures of Winnie the Pooh (ABC, 1988–1991)

- The Book of Pooh (*) (Disney Channel (Playhouse Disney), 2001–2003)

- My Friends Tigger & Pooh (Disney Channel (Playhouse Disney), 2007–2010)

- Mini Adventures of Winnie the Pooh (Disney Junior, 2011–2014[43])

Magical World of Winnie the Pooh (Note: These are episodes from The New Adventures of Winnie the Pooh) (*): Puppet/live-action show

Holiday TV specials

- 1991: Winnie the Pooh and Christmas Too, included in A Very Merry Pooh Year

- 1996: Boo to You Too! Winnie the Pooh, included in Pooh's Heffalump Halloween Movie

- 1998: A Winnie the Pooh Thanksgiving, included in Seasons of Giving

- 1999: A Valentine for You

Direct-to-video shorts

Direct-to-video features

- 1997: Pooh's Grand Adventure: The Search for Christopher Robin

- 1999: Seasons of Giving*

- 2001: The Book of Pooh: Stories from the Heart

- 2002: A Very Merry Pooh Year*

- 2004: Springtime with Roo

- 2005: Pooh's Heffalump Halloween Movie

- 2007: Super Sleuth Christmas Movie

- 2009: Tigger and Pooh and a Musical Too

- 2010: Super Duper Super Sleuths

These features integrate stories from The New Adventures of Winnie the Pooh and/or the holiday specials with new footage.

Video games

The following games are based on Disney's Winnie the Pooh.

| Main title / alternate title(s) | Developer | Release date | System(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Winnie the Pooh in the Hundred Acre Wood | Sierra On-Line | 1984 | Amiga, Apple II, Atari ST, Commodore 64, DOS |

| A Year at Pooh Corner | Novotrade, Sega | 1994 | Sega Pico |

| Ready for Math with Pooh | Disney Interactive Studios | 1997 | Microsoft Windows |

| Ready to Read with Pooh | Disney Interactive Studios | 1997 | Microsoft Windows |

| Tigger's Honey Hunt | Doki Denki, NewKidCo | 2000 | PlayStation, Microsoft Windows, Nintendo 64 |

| Winnie the Pooh: Adventures in the 100 Acre Wood | Tose, NewKidCo | 2000 | Game Boy Color |

| Disney's Winnie the Pooh: Preschool | Hi Corp, Atlus | 2001 | PlayStation |

| Disney's Pooh's Party Game: In Search of the Treasure | Doki Denki, SCEE, Electronic Arts, Tomy Corporation | 2001 | PlayStation, Microsoft Windows |

| Kuma no Pooh-San: Mori no Nakamato 123 | Atlus | 2001 | PlayStation |

| Pooh and Tigger's Hunny Safari | Digital Eclipse, Electronic Arts, Ubisoft | 2001 | Game Boy Color |

| Disney's Winnie the Pooh's Rumbly Tumbly Adventure | Hi Corp, Atlus | 2002 | PlayStation |

| Piglet's Big Game | Doki Denki Studio, Disney Interactive Studios, THQ, Gotham Games | 2003 | Nintendo GameCube, PlayStation 2, Game Boy Advance |

| Pooh's Hunny Pot Challenge | Walt Disney Internet Group | 2003 | Mobile phone |

| Pooh's Pairs | Walt Disney Internet Group | 2003 | Mobile phone |

| Tigger's Bouncin' Time | Walt Disney Internet Group | 2003 | Mobile phone |

| Pooh's Hunny Blocks | Walt Disney Internet Group | 2003 | Mobile phone |

| Winnie the Pooh's Rumbly Tumbly Adventure | Phoenix Games Studio, Ubisoft | 2005 | Game Boy Advance, Nintendo GameCube, PlayStation 2, mobile phone |

| Kuma no Pooh-San: 100 Acre no Mori no Cooking Book | Disney Interactive Studios | 2011 | Nintendo DS |

| Disney's Winnie the Pooh and the Honey Tree Animated Storybook | Disney Interactive Studios | 2014 | Microsoft Windows |

Winnie the Pooh also appears in the Square Enix/Disney crossover series Kingdom Hearts.

Legacy

Winnie the Pooh has inspired multiple texts to explain complex philosophical ideas. Benjamin Hoff used Milne's characters in The Tao of Pooh and The Te of Piglet to explain Taoism. Similarly, Frederick Crews wrote essays about the Pooh books in abstruse academic jargon in The Pooh Perplex and Postmodern Pooh to satirise a range of philosophical approaches.[44] Pooh and the Philosophers by John T. Williams uses Winnie the Pooh as a backdrop to illustrate the works of philosophers, including Descartes, Kant, Plato and Nietzsche.[45] "Epic Pooh" is a 1978 essay by Michael Moorcock that compares much fantasy writing to A.A. Milne's as work intended to comfort, not challenge.

One of the best known characters in British children's literature, a 2011 poll saw Winnie the Pooh voted onto the list of icons of England.[46] Forbes magazine ranked Pooh the most valuable fictional character in 2002, with merchandising products alone generating more than $5.9 billion that year.[47] In 2005, Pooh generated $6 billion, a figure surpassed by only Mickey Mouse.[48] In 2006, Pooh received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, marking the 80th birthday of Milne's creation.[48] The bear is such a popular character in Poland that a Warsaw street is named for him, Ulica Kubusia Puchatka. There is also a street named after him in Budapest (Micimackó utca).[49]

In music, Kenny Loggins wrote the song "House at Pooh Corner", which was originally recorded by the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band.[50] Loggins later rewrote the song as "Return to Pooh Corner", featuring on the album of the same name in 1991. In Italy, a pop band took their name from Winnie, and were titled Pooh. In Estonia there is a punk/metal band called Winny Puhh.

In the "sport" of Poohsticks, competitors drop sticks into a stream from a bridge and then wait to see whose stick will cross the finish line first. Though it began as a game played by Pooh and his friends in the book The House at Pooh Corner and later in the films, it has crossed over into the real world: a World Championship Poohsticks race takes place in Oxfordshire each year. Ashdown Forest in England where the Pooh stories are set is a popular tourist attraction, and includes the wooden Pooh Bridge where Pooh and Piglet invented Poohsticks.[51] The Oxford University Winnie the Pooh Society was founded by undergraduates in 1982.

Censorship in China

In the People's Republic of China, images of Pooh were censored in mid-2017 from social media websites, when internet memes comparing Chinese president Xi Jinping to Pooh became popular.[52] The 2018 film Christopher Robin was also denied a Chinese release.

When Jinping visited the Philippines, protestors posted images of Pooh on social media.[53] Other politicians have been compared to Winnie-the-Pooh characters alongside Jinping, including Barack Obama as Tigger, Carrie Lam, Rodrigo Duterte and Peng Liyuan as Piglet, and Fernando Chui and Shinzo Abe as Eeyore.[54]

Pooh's Chinese name (Chinese: 小熊维尼; lit. 'little bear Winnie') has been censored from video games such as Overwatch, World of Warcraft, Pubg, Arena of Valor,[55] and Devotion.[56] Images of Pooh in Kingdom Hearts III were also blurred out.[57]

References

- ^ McDowell, Edwin. "Winnie Ille Pu Nearly XXV Years Later", The New York Times (18 November 1984). Retrieved 2 January 2010.

- ^ "Pooh celebrates his 80th birthday". BBC News. Retrieved 20 July 2015

- ^ Ford, Rebecca (28 February 2007) "Happy Birthday Pooh", Daily Express. Retrieved 20 July 2015

- ^ "The Adventures of the Real Winnie-the-Pooh. The New York Public Library.

- ^ "Winnie the Pooh's Canadian beginnings". The Spectator, – Hamilton, Ont. 2 August 1997, Page: W.13

- ^ "Winnie". Historica Minutes, The Historica Foundation of Canada. Retrieved 30 May 2008.

- ^ Safire, William. “Whence Poo-Bah”, GASBAG, vol. 24, no. 3, issue 186, January/February 1993, p. 28.

- ^ Willard, Barbara (1989). The Forest – Ashdown in East Sussex. Sussex: Sweethaws Press.. Quoted from the Introduction, p. xi, by Christopher Milne.

- ^ Willard (1989). Quoted from the Introduction, p. xi, by Christopher Milne.

- ^ Hope, Yvonne Jefferey (2000). "Winnie-the-Pooh in Ashdown Forest". In Brooks, Victoria (ed.). Literary Trips: Following in the Footsteps of Fame. Vol. 1. Vancouver, Canada: Greatest Escapes. p. 287. ISBN 0-9686137-0-5.

- ^ "About the E. H. Shepard archive". University of Surrey. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ^ "Plans to improve access to Pooh Bridge unveiled". BBC News. Retrieved 11 November 2012

- ^ "Appeal to save Winnie the Pooh's bridge". BBC News. Retrieved 11 November 2012

- ^ "Celebrate Winnie-The-Pooh's 90th with a Rare Recording (And Hunny)". NPR. 20 July 2015.

- ^ a b "A Children's Story by A. A. Milne". London Evening News. 24 December 1925. p. 1.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Thwaite, Ann (2004). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: Alan Alexander Milne. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Kennedy, Maev (4 October 2009). "Pooh sequel returns Christopher Robin to Hundred Acre Wood". The Guardian. UK. p. 15.

- ^ "Winnie-the-Pooh sequel details revealed". Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- ^ "Listen to the moment Winnie-the-Pooh meets penguin friend in new book". BBC News. 19 September 2016.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) - ^ "Winnie the Pooh meets the Queen in a new story". BBC News. 19 September 2016.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) - ^ "The Merchant of Child". Fortune. November 1931. p. 71.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ McElway, St. Claire (26 October 1936). "The Literary Character in Business & Commerce". The New Yorker.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Leonard, Devin (20 January 2003). "The Curse of Pooh". Fortune. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "The Pooh Files" Archived 5 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine The Albion Monitor.

- ^ Nelson, Valerie J (20 July 2007). "Shirley Slesinger Lasswell, 84; fought Disney over Pooh royalties". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Judge dismisses Winnie the Pooh lawsuit" Archived 12 October 2004 at the Wayback Machine The Disney Corner.

- ^ James, Meg (26 September 2007). "Disney wins lawsuit ruling on Pooh rights". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 26 September 2007.

- ^ "Winnie the Pooh goes to court" USA Today 6 November 2002. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- ^ "Justices won't hear copyright appeal by relative of Winnie the Pooh". USA Today. Associated Press. 26 June 2006. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- ^ "Disney loses court battle in Winnie the Pooh copyright case". ABC News. 17 February 2007. Retrieved 15 May 2008.

- ^ James, Meg (29 September 2009). "Pooh rights belong to Disney, judge rules". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 5 October 2009.

- ^ Shea, Joe (4 October 2009). "The gordian knot of Pooh rights is finally untied in federal court". The American Reporter. Retrieved 5 October 2009. [dead link]

- ^

"Hastings Marionettes: Will Open Holiday Season at Guild Theatre on Saturday". The New York Times. 22 December 1931. p. 28.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "Ian Carmichael And Full Cast – The House at Pooh Corner – HMV Junior Record Club – UK – 7EG 117". 45cat. 23 July 2010. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ^ "Winnie the Pooh". OCLC WorldCat. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- ^ "Tigger comes to the forest: and other stories". OCLC WorldCat. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- ^ "His Master's Voice Speaks Again". Playthings. November 1932.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "Russian animation in letters and figures | "Winnie the Pooh"". Animator.ru. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ Soviet version of AA Milne classic hits British screens | Daily Mail Online

- ^ Biography: Willie Rushton. BBC. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ^ Fleming Jr., Mike. "Disney Sets Live-Action 'Winnie The Pooh' Film; Alex Ross Perry To Write". Deadline. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ^ Lincoln, Ross A. (18 November 2016). "Marc Forster To Helm Live-Action 'Christopher Robin' Based On 'Winnie The Pooh' Character". Deadline.

- ^ "Mini Adventures of Winnie the Pooh". IMDb. 22 August 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- ^ spiked-culture |Article |Pooh-poohing postmodernism. Spiked-online.com. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ^ Sonderbooks Book Review of Pooh and the Philosophers. Sonderbooks.com (20 April 2004). Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- ^ "ICONS of England – the 100 ICONS as voted by the public". Culture 24 News. 20 July 2015.

- ^ "Top-Earning Fictional Characters". Forbes (New York). 25 September 2003. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ a b "Pooh joins Hollywood Walk of Fame". BBC. Retrieved 24 November 2014

- ^ "Google Maps". Google Maps. 1 January 1970. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ "House at Pooh Corner by Loggins and Messina Songfacts". Songfacts.com. 14 October 1926. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ Plans to improve access to Pooh Bridge unveiled. BBC. Retrieved 15 October 2011

- ^ McDonell, Stephen (17 July 2017). "Why China censors banned Winnie the Pooh". BBC News. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) - ^ "Lots of Winnie the Pooh on your newsfeeds? It's Filipino netizens' burn against Chinese leader Xi". cnn. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ^ "Netizens cast Hong Kong leader Carrie Lam as the Piglet to Xi Jinping's Winnie the Pooh". Shanghaiist. 24 October 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ^ Trent, John F. (20 March 2019). "Report: "Winnie the Pooh" Censored in World of Warcraft, PUBG, and Arena of Valor in China". Bounding Into Comics. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ^ Horti, Samuel (23 February 2019). "Devotion review bombed by Chinese Steam users over Winnie the Pooh meme". PC Gamer. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ^ https://kotaku.com/chinese-game-site-censors-winne-the-pooh-in-kingdom-hea-1830618072

External links

- Winnie-the-Pooh at Curlie

- The original bear, with A. A. Milne and Christopher Robin, at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- The real locations, from the Ashdown Forest Conservators

- Winnie-the-Pooh at the New York Public Library

- "Winnie the Pooh saga turns 100 years old", CBC News, 24 August 2014.

- "The skull of the 'real' Winnie goes on display", BBC News, 20 November 2015.