Customs and etiquette in Japanese dining

This article, Customs and etiquette in Japanese dining, has recently been created via the Articles for creation process. Please check to see if the reviewer has accidentally left this template after accepting the draft and take appropriate action as necessary.

Reviewer tools: Inform author |

Comment: Also a Draft:Customs and etiquette in Japanese dining which would be the likely article title should this be approved. AngusWOOF (bark • sniff) 03:31, 28 May 2019 (UTC)

Comment: Also a Draft:Customs and etiquette in Japanese dining which would be the likely article title should this be approved. AngusWOOF (bark • sniff) 03:31, 28 May 2019 (UTC)

Japanese dining etiquette is a set of rules governing specific expectations which need to be followed when eating. It outlines general standards of how to act and respond in various dining situations. This may differ across countries and culture. In Japan, there are many different kinds of dining etiquette that one should be aware of. The failure to demonstrate basic dining etiquette may lead to misunderstanding and misconception about the Japanese culture. By correctly following the dining etiquette of Japan, general manners and respects towards the Japanese culture can be demonstrated.

Japanese Dining Etiquette

Basic Dining Etiquette

If a series of small foods are served, it is important to fully finish off one dish prior to moving on to the next one. However, it is not considered to be compulsory to complete the entire dishes, especially the broth from ramen or similar kinds. [1] Before starting to eat a meal, saying itadakimasu, a polite phrase meaning "I receive this food", is a way to show gratitude towards the person that prepared the meal. This can be done in a praying motion, which is gathering both hands together, or more simply, by bowing the head. Upon finishing the meal, gratitude is expressed again by saying gochiso sama deshita, meaning "it was quite a feast". [2] The dishes or plates should be placed back to their original position after the meal.

Distinctive Characteristics

Japanese dining etiquette has distinctive characteristics in general, as follows.[3]

- Chopsticks are used in every meal.

- When eating, plates are picked up and held at chest-level except when the size of a plate is too large to do so.

- When drinking soup, the soup is drunk up from the bowl that is held straight, as an alternative to scooping the soup with a spoon.

- Finishing what is on a plate is viewed as a polite act.

- It is prohibited to rest an elbow on a table.

Oshibori (お絞り; おしぼり)

Oshibori, or also known as a wet towel, is a small white hand towel that had previously been soaked in clean water and wrung out to have it in a damped condition. In Japan, it is served in most of the dining places in the form that it is folded and rolled up.[4] Either a hot or cold towel is served depending on the season. As for the dining etiquette, use the provided Oshibori to clean both hands, before starting a meal. It is only used to wipe out hands and therefore it should not be used to wipe face or used for other purposes, as it is considered impolite. [5]

Drinking

When it comes to drinking alcoholic beverages in Japan, there are several points to keep in mind. The person who first pours the alcoholic drink in the glasses of others, the person should be holding the bottle of the alcoholic drink with both hands simultaneously. The person who receives the pouring must hold the cup firmly, and politely ask whether or not the person who just served would want to have poured back after the pouring has finished.[6] When drinking with a group, hold on from drinking until each glass is filled up. To celebrate drinking with the group, shout out the word Kanpai (lit. cheers) while raising the glass at the same time, this word is shouted with the group simultaneously. When hosts empty their glasses, others should attempt to do the same thing as well. [7]

Common Mistakes

If a Japanese food contains clams, it is common to find empty clam shells placed in different bowls after one finishes the meal. However, this is regarded as an impolite deed in Japan, the empty clam shells should be placed inside the bowl where the food was originally served. A deed of abandoning chopsticks on the table after when a meal has finished happens frequently. However, in Japan, it may signal that the meal has not finished, and therefore it is suggested to place the chopsticks sideways across on to a plate or bowl when the meal has finished.[8] Talking too much when dining is not very welcoming in Japan, as maintaining some silence while eating a meal is importantly valued, hence avoid forcing unnecessary conversations when eating with someone. [9]

Religion

In the 6th and 7th century of Japan, many influences arrived in Japan through Korea, which included the import of Buddhism. Across the different types of pre-existing religions such as Confucian and Shinto, Buddhism had become the main religion during the 6th century. Today, Buddhism is the firm roots of the vital dining etiquette that is universally practised in Japan.[10]

Behind the phase that is used to show a gratitude for whoever that was involved in making the meal to take place (i.e. farmers, fishermen, parents, etc), itadakimasu, the traditional Japanese Buddhist foundation is associated, the meaning of the phases is focused on the origin of the food rather than on the coming feast.[11] The belief from Buddhism that every object has a spirit to be recognised is applied on the phrase, manifesting both gratitude and honour to pay respect to the lives used to make the food, such as cook, animals, farmers, and plants. [12]

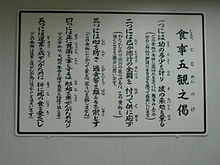

However, the way of saying itadakimasu is different at Buddhist temples in Japan. Monks and nuns in a Buddhist temple are subject to say two or more of different verses before a meal, depending on the customary practices at each temple. The Five Reflections (五観の偈) are one of the verses that are said to express gratitude towards the meal. The English translation of the Five Reflections are as follows:[13]

- Look through the food. Think about how nature and people’s hard labour have accumulated to took part in the creation of the food.

- Reflect upon your behaviour towards others. Consider whether your virtue and previous actions deserve the meal in front of you.

- Contemplate whether your own spirit is truthful and purified. A mind that is full of the three greatest evils (greed, anger and ignorance) will make a disturbance when trying to genuinely appreciate or savour the food.

- Remind that good food is better than medicine. Consuming a good food is a way to rejuvenate tiredness, it is not a way to fulfil sensory pleasure.

- Eat with gratitude while appreciating all beings, remind of the Bodhisattva vows to bring others with enlightenment.

Food and Etiquette

Ramen (ラーメン)

When eating ramen or similar types, it is acceptable to make slurping sounds as it is the way to express appreciation for the meal and to strengthen the flavour of ramen. [14] Noodles are cooled and hence enhances the flavour during the slurping process. [15] However, making eating sounds of munching and burping are not very favourable as it may displease people around. The general Japanese ramen etiquette postulates that ramen should be eaten by using both chopsticks and spoon. The noodles and toppings on ramen should be eaten with chopsticks while the soup should be drunk with a spoon. [16]

Sushi (寿司, 鮨)

Sushi (寿司 or 鮨) is one of the most famous dishes of Japan, which comes with many different varieties, and therefore there is a certain dining etiquette to follow. It is allowed to eat sushi with bare hands, however, sashimi is eaten with chopsticks.[17] When shoyu (lit. soy sauce) is served together with nigiri-sushi (lit. sushi with a fish topping), pick up the sushi and dip the part of the fish topping into the shoyu, not the part of rice. Having rice to absorb shoyu too much would change the original taste of the nigiri-sushi, and trying to dip rice into the shoyu may also cause the whole sushi to fall apart, consequently dropping rice on to the shoyu plate. An appearance of rice floating around on the shoyu plate is not considered as a taboo in Japanese culture; however, it may leave a bad impression by doing so. [7] In a case when shoyu has to be poured into a bowl, pour only a tiny amount since pouring a large portion may waste an unnecessary amount of shoyu, which is one of the serious taboos in Japan. [18]

Chopsticks (Ohashi)

Chopsticks must be picked up with the right hand. It is then held firm while considering three key points, that the thumb is placed just like how a pencil is held, ensure the thumb is touched with the upper part of the chopstick. Another part of the chopstick, the lower part is stood still and rest in the index finger. Make sure that arm is relaxed so it forms a gentle curve.[19]

The followings are the most common taboos when using chopsticks as the dining utensil in Japan.

Mayoi Bashi (迷い箸; まよいばし)

Mayoi-bashi refers to an act of hovering or waving chopsticks over the dishes set on a table, to choose which food to eat first. This is regarded as inappropriate behaviour, as this portrays the personality of impatience and greedy in the context of Japanese dining etiquette. [20] To avoid, it is important to decide which food to eat before using chopsticks to move the food onto a plate.

Namida Bashi (涙箸; なみだばし)

Namida-bashi describes that food should not be carried with chopsticks if the food has been dipped into a soy sauce or similar kind. The reason behind this is to make sure that any sauce or liquid attached to the food does not drip from the food or chopsticks. [21] It is considered to be immature and unclean when the sauce or liquid from the food is dripped on the table.

Odori Bashi (踊り箸; おどりばし)

Talking without putting chopsticks down onto the table, for example, using chopsticks as to provide gestures for better communication, is regarded as extremely rude in regards to Japanese dining etiquette. [22]

Tate Bashi (たて箸; たてばし)

Making chopsticks to stand upright, for example, placing them vertically into a rice bowl, is strictly prohibited due to its deep association with Buddhist funeral rites. If the chopsticks are placed in this particular way, it may offend Japanese people in the way that it reminisces about a site of Japanese funeral which claims to bring a bad fortune. [22] The ritual explains, when one passes away in Japan, one's family or close relative is expected to organise a bowl of rice with chopsticks inside situated vertically. [23] More preferred way of placing chopsticks in Japan is placing the chopsticks across the top of a bowl, which is referred to as "watashi-bashi". However, watashi-bashi is only suitable for casual occasions, and therefore it is a good idea to refrain when confronting situations where it needs to be more formal. In a formal occasion, it is best to use a chopsticks rest (hashi-oki). Otherwise, rest the chopsticks on top of the paper sleeve which the chopsticks were wrapped with.

Hiroi Bashi (拾い箸; ひろいばし)

Sharing or moving food around chopsticks to chopsticks is not acceptable behaviour in Japan. This deed is also closely related to Buddhist funeral rites; remaining bones after cremating a body are moved into an urn with chopsticks to chopsticks by family and/or close relatives.[24]

See also

- Etiquette in Japan

- Etiquette in Asia

- Etiquette in Europe

- Etiquette in Australia and New Zealand

- Table manners

- Table manners in North America

- Eating utensil etiquette

- Worldwide etiquette

References

- ^ Chua, Jasmine (2018-01-04). "Etiquette Series – Japanese Table Manners". Japaniverse Travel Guide. Retrieved 2019-05-11.

- ^ Creative, Tokyo. "Japanese Table Manners". Tokyo Creative. Retrieved 2019-05-11.

- ^ "Japanese Table Manners" (PDF). Okaya International Center. 15 July 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Writers, YABAI. "The Comforting Culture of Wet Towels (Oshibori) in Japan | YABAI - The Modern, Vibrant Face of Japan". YABAI. Retrieved 2019-05-11.

- ^ "Japanese Dining Etiquette". Chopstick Chronicles. 2015-11-13. Retrieved 2019-05-11.

- ^ "Dining etiquette in Asia". International Travel News. Vol. 23, no. 11. Martin Publications. January 1999. p. 163 – via Cengage Learning.

- ^ a b "A Step-by-Step Guide to Japanese Table Manners and Chopstick Etiquette". TripSavvy. Retrieved 2019-05-12.

- ^ "An essential guide to Japanese dining etiquette". Japan National Tourism Organization. Retrieved 2019-05-15.

- ^ "Dining Etiquette" (PDF). University of Notre Dame. 15 April 2014.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Visočnik, N. (2004). Food and Identity in Japan. University of Ljubljana, Slovenia.

- ^ "Japanese Table Manners: Itadakimasu! Gochisousama!". VOYAPON. 2016-04-04. Retrieved 2019-05-11.

- ^ "The Meaning Behind "Itadakimasu" - How to Learn Japanese - NihongoShark.com". nihongoshark.com. Retrieved 2019-05-11.

- ^ "Gokan no Ge". team SHOJIN. Retrieved 2019-05-16.

- ^ Baker, Lucy (2019-03-07). "Guide to Japanese Table Manners and Dining Etiquette". Tokyo by Food - Cooking Classes and Food Tour in Tokyo. Retrieved 2019-05-11.

- ^ "10 Unique Japanese Eating Etiquette Rules -". 2016-07-29. Retrieved 2019-05-11.

- ^ Mundy, Jane (2012). "A YEN FOR RAMEN" (PDF). Nuvo Magazine.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ "How to Eat Sushi (Sushi Etiquette)". The Sushi FAQ. Retrieved 2019-05-12.

- ^ "You Might Be Eating Sushi Incorrectly". TripSavvy. Retrieved 2019-05-15.

- ^ Japanology (2016-08-25), BEGIN Japanology - Chopsticks, retrieved 2019-05-05

- ^ "Chopstick Crimes | Japanzine". Retrieved 2019-05-12.

- ^ Sakura. "10 Japanese Chopstick Don'ts". Living Language. Retrieved 2019-05-12.

- ^ a b "13 Japanese chopsticks taboos You Should Know About". Coto Japanese Academy. 2016-07-28. Retrieved 2019-05-05.

- ^ "Japanese Chopsticks Etiquette - 12 Things Not to Do!". Smile Nihongo. 2016-08-01. Retrieved 2019-05-12.

- ^ "Japanese Chopstick Etiquette + Punishments -". Nihon Scope. 2016-02-18. Retrieved 2019-05-12.

Further reading

- Wang, Edward (2015). Chopsticks: A Cultural and Culinary History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-02396-3.

- Bardsley, Jan; Miller, Laura (2011). Manners and mischief gender, power, and etiquette in Japan. University of California Press. ISBN 1-283-27814-6.

- Murakami, Ken (1996). Passport Japan your pocket guide to Japanese business, customs & etiquette. San Rafael, Calif. : World Trade Press. ISBN 1-885073-17-8.

- Rath, Eric C. (2016). Japan's cuisines : food, place and identity. London : Reaktion Books. ISBN 9781780236919.

- Cwiertka, Katarzyna J. (2015). Modern Japanese Cuisine: Food, Power and National Identity. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1780234533.

External links

- Complete guide to Japanese dining etiquette

- An essential guide to Japanese dining etiquette

- Dining Etiquette From Around The World

- Japanese food etiquette

- A Guide To Dining Etiquette Around The World