Peopling of India

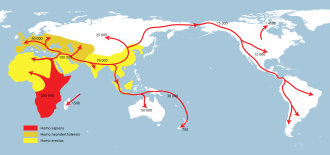

The peopling of India refers to the migration of Homo sapiens into the Indian subcontinent. Anatomically modern humans settled India in multiple waves of early migrations, over tens of millennia.[1] The first migrants came with the Southern Coastal dispersal, ca. 65,000 years ago, whereafter complex migrations within south and southeast Asia took place. With the onset of farming the population of India changed significantly by the migration of Iranian agri-culturalists and the Indo-Europeans, while the migrations of the Munda people and the Tibeto-Burmese tribes from East Asia also added new elements.

Ancestral components in the Indian population

A series of studies since 2009-2019 have shown that the Indian subcontinent harbours two major ancestral components,[2][3][4] namely the Ancestral North Indians (ANI) which is broadly related to West Eurasians and the Ancestral South Indians (ASI) which is clearly distinct from ANI.[2][note 1][6] As no "AASI" ancient DNA is available, the indigenous Andamanese (exemplified by the Onge, a possibly distantly related population native to the Andaman Islands) is used as an (imperfect) proxy.[2][7] Shinde et al. 2019 found either Andamanese or East Siberian hunter-gatherers fit as proxy for AASI "due to shared ancestry deeply in time".[8] Additionally East Asian ancestry makes up the third ancestral component and is largely linked to the migration of Austroasiatic and Tibeto-Burmese groups[9][10], but also Turkic and Austronesian groups.[11][12]

A number of studies since 2018 have presented a refined model of South Asian ancestry with the help of Ancient DNA.[6][8] These studies also concluded that more samples are needed to get the full picture of South Asian population history.[6]

AASI

Narashimhan et al 2018 study introduced AASI - “Ancient Ancestral South Indian (AASI)-related - a hypothesized South Asian Hunter-Gathere lineage" which represents "an anciently divergent branch of Asian human variation that split off around the same time that East Asian, Onge and Australian ancestors separated from each other" and is deeply related to Andaman islanders exemplified by the Onge as proxy.[13] Shinde et al. 2019 found either Andamanese or East Siberian hunter-gatherers fit as proxy for AASI "due to shared ancestry deeply in time".[8] ASI was synonyms to AASI before 2018.[6]

"This finding is consistent with a model in which essentially all the ancestry of present-day eastern and southern Asians (prior to West Eurasian-related admixture in southern Asians) derives from a single eastward spread, which gave rise in a short span of time to the lineages leading to AASI, East Asians, Onge, and Australians."[14]

ASI

Narasimhan et al. 2018 and Shinde et al. 2019 analyzed ancient DNA remains from the archaeological sites related to Indus Valley civilization, they found them to have a dual ancestry: AASI-related ancestry and Neolithic Iran-related ancestry.[15] Narasimhan et al. 2018 study labels this group "Indus Periphery-related".[14]

"The only fitting two-way models were mixtures of a group related to herders from the western Zagros mountains of Iran and also to either Andamanese hunter-gatherers or East Siberian hunter-gatherers (the fact that the latter two populations both fit reflects that they have the same phylogenetic relationship to the non-West Eurasian-related component likely due to shared ancestry deeply in time)"[16]

ASI formed as mixture of "Indus Periphery-related" group who moved south and mixed further with AASI-related ancestry. "Indus Periphery-related" group did not carry steppe admixture and were instead mixture of Neolithic Iran-related ancestry and hypothesized AASI-related ancestry.[14]

ANI

Lazaridis et al. (2016) with the help of ancient DNA from neolithic Iran and bronze age steppe found that ANI-related ancestry in South Asians can be modeled as a mix of ancestry related to both early farmers of Iran and to people of the Bronze Age Eurasian steppe.[17]

Narasimhan et al. (2018) and Shinde et al (2019) ancient DNA study came to conclusion that neolithic Iran-related ancestry was present in South Asia before the arrival of steppe ancestry.[14][16] ANI formed out of a mixture of "Indus Periphery-related groups" and migrants from Bronze age steppe.[14]

East Asian components

According to Basu et al. (2016), mainland India harbors two additional distinct ancestral components which have contributed to the gene pools of the Indian subcontinent,[note 2] namely Ancestral Austro-Asiatic (AAA) and Ancestral Tibeto-Burman (ATB). While Tibeto-Burmese ancestry is predominantly found in Northeast India and parts of northern India, Austroasiatic ancestry is commonly found along the eastern Indo-Gangetic Plain.[9][18]

Yunusbayev et al. (2015) notes that Turkic peoples had some influence on the population history of India, especially northern India.[19] Austronesian influence is found along the coastline of India, especially southern India and in Sri Lanka.[20]

A genetic analysis from Chaubey et al. 2015 found East Asian-related ancestry in Andamanese people. He estimates 32% East Asian ancestry in the Ongeand 31% in the Great Andamanese.[21]

2009-2018 studies

Reich et al. (2009) study found that Indian subcontinent harbours two major ancestral components,[2][3][4] namely the Ancestral North Indians (ANI) which is "genetically close to Middle Easterners, Central Asians, and Europeans", and the Ancestral South Indians (ASI) which is clearly distinct from ANI.[2][note 3] These two groups mixed in India between 4,200 and 1,900 years ago (2200 BCE-100 CE), whereafter a shift to endogamy took place,[4] possibly by the enforcement of "social values and norms" during the Hindu Gupta rule.[22] Reich et al. stated that “ANI ancestry ranges from 39-71% in India, and is higher in traditionally upper caste and Indo-European speakers”.[2]

Moorjani et al. (2013) proposed three scenarios regarding the bringing together of the two groups:

- Migrations before the development of agriculture (8,000–9,000 years before present BP).

- Migration of western Asian people together with the spread of agriculture, maybe up to 4,600 years BP.

- Migrations of western Eurasians from 3,000 to 4,000 years BP.[23] Moorjani suggests that the ANI and the ASI were plausibly present "unmixed" in India before 2,200 BC.[4]

While Reich notes that the onset of admixture coincides with the arrival of Indo-European language,[24] according to Moorjani et al. (2013) these groups were present "unmixed" in India before the Indo-Aryan migrations.[4] Gallego Romero et al. (2011) propose that the ANI component came from Iran and the Middle East,[25] less than 10,000 years ago,[26][note 4] while according to Lazaridis et al. (2016) ANI is a mix of "early farmers of western Iran" and "people of the Bronze Age Eurasian steppe".[27] Several studies also show traces of later influxes of maternal genetic material[28][29] and of paternal genetic material related to ANI and possibly the Indo-Europeans.[2][30][31]

While Reich notes that the onset of admixture coincides with the arrival of Indo-European language,[24] according to Moorjani et al. (2013) these groups were present "unmixed" in India before the Indo-Aryan migrations.[4] Gallego Romero et al. (2011) propose that the ANI component came from Iran and the Middle East,[25] less than 10,000 years ago,[26][note 4] while according to Lazaridis et al. (2016) ANI is a mix of "early farmers of western Iran" and "people of the Bronze Age Eurasian steppe".[27] Several studies also show traces of later influxes of maternal genetic material[28][29] and of paternal genetic material related to ANI and possibly the Indo-Europeans.[2][30][31]

According to Basu et al. (2016), the ASI are earliest settlers in India, possibly arriving on the southern exit wave out of Africa.[32] These two groups mixed in India between 4,200 and 1,900 years ago (2200 BCE-100 CE), whereafter a shift to endogamy took place,[4] possibly by the enforcement of "social values and norms" by the "Hindu Gupta rulers."[22]

According to Basu et al. (2016), the populations of the Andaman Islands archipelago form a distinct, fifth ancestry, which is "coancestral to Oceanic populations."[33]

2018-2019 studies

Narasimhan et al. (2018) conclude that ANI and ASI were formed in the 2nd millennium BCE.[34] They were preceded by a mixture of AASI hypothesized South Asian Hunter-Gathere lineage; and Iranian agriculturalists who arrived in India ca. 4700–3000 BCE, and "must have reached the Indus Valley by the 4th millennium BCE".[34] According to Narasimhan et al., this mixed population, which probably was native to the Indus Valley Civilisation, "contributed in large proportions to both the ANI and ASI", which took shape during the 2nd millennium BCE. ANI formed out of a mixture of "Indus Periphery-related groups" and migrants from the steppe, while ASI was formed out of "Indus Periphery-related groups" who moved south and mixed further with local hunter-gatherers. The ancestry of the ASI population is suggested to have averaged about 73% from the AASI and 27% from Iranian-related farmers. Narasimhan et al. observe that samples from the Indus periphery group are always mixes of the same two proximal sources of AASI and Iranian agriculturalist-related ancestry; with "one of the Indus Periphery individuals having ~42% AASI ancestry and the other two individuals having ~14-18% AASI ancestry" (with the remainder of their ancestry being from the Iranian agriculturalist-related population).[34]

Yelmen et al. (2019) study shows that the native South Asian genetic component (ASI) is distinct from the Andamanese and that the Andamanese are thus an imperfect and imprecise proxy for ASI. According to Yelmen et al, the Andamanese component (represented by the Andamanese Onge) was not found in the northern Indian Gujarati (ASI is was not detected in the Gujarati when the Onge were used as a proxy), and thus it is suggested that the South Indian tribal Paniya people (who are believed to be of largely ASI ancestry) would serve as a better proxy than the Andamanese (Onge) for the "native South Asian" component in modern South Asians.[35]

Two genetic studies (Shinde et al. 2019 and Narasimhan et al. 2019,) analysing remains from the Indus Valley civilisation (of parts of Bronze Age Northwest India and East Pakistan), found them to have a mixture of ancestry: Shinde et al. found their samples to have about 50-98% of their genome from peoples related to early Iranian farmers, and from 2-50% of their genome from native South Asian hunter-gatherers sharing a common ancestry with the Andamanese, with the Iranian-related ancestry being predominant on average. And the samples analyzed by Narasimhan et al. had 45–82% Iranian farmer-related ancestry and 11–50% AASI (or Andamanese-related hunter-gatherer ancestry). The analysed samples of both studies have little to none of the "Steppe ancestry" component associated with later Indo-European migrations into India. The authors found that the respective amounts of those ancestries varied significantly between individuals, and concluded that more samples are needed to get the full picture of Indian population history.[36][37]

Paleolithic

First modern human settlers

Pre- or post-Toba

The dating of the earliest successful migration modern humans out of Africa is a matter of dispute.[38] It may have pre- or post-dated the Toba catastrophe, a volcanic super eruption that took place between 69,000 and 77,000 years ago at the site of present-day Lake Toba. According to Michael Petraglia, stone tools discovered below the layers of ash deposits in India at Jwalapuram, Andhra Pradesh point to a pre-Toba dispersal. The population who created these tools is not known with certainty as no human remains were found.[38] An indication for post-Toba is haplogroup L3, that originated before the dispersal of humans out of Africa, and can be dated to 60,000–70,000 years ago, "suggesting that humanity left Africa a few thousand years after Toba."[38]

It has been hypothesized that the Toba supereruption about 74,000 years ago destroyed much of India's central forests, covering it with a layer of volcanic ash, and may have brought humans worldwide to a state of near-extinction by suddenly plunging the planet into an ice-age that could have lasted for up to 1,800 years.[39] If true, this may "explain the apparent bottleneck in human populations that geneticists believe occurred between 50,000 and 100,000 years ago" and the relative "lack of genetic diversity among humans alive today."[39]

Since the Toba event is believed to have had such a harsh impact and "specifically blanketed the Indian subcontinent in a deep layer of ash," it was "difficult to see how India's first colonists could have survived this greatest of all disasters."[40] Therefore, it was believed that all humans previously present in India went extinct during, or shortly after, this event and these first Indians left "no trace of their DNA in present-day humans" – a theory seemingly backed by genetic studies.[41]

Pre-Toba tools

Research published in 2009 by a team led by Michael Petraglia of the University of Oxford suggested that some humans may have survived the hypothesized catastrophe on the Indian mainland. Undertaking "Pompeii-like excavations" under the layer of Toba ash, the team discovered tools and human habitations from both before and after the eruption.[42] However, human fossils have not been found from this period, and nothing is known of the ethnicity of these early humans in India.[42] Recent research also by Macauly et al. (2005)[43][44] and Posth et al. (2016),[45] also argue for a post-Toba dispersal.[44] Early Stone Age hominin fossils have been found in the Narmada valley of Madhya Pradesh. Some have been dated to 200- 700,000 BP. It is uncertain what species they represent.[46]

Post-Toba Southern Coastal dispersal

By some 70-50,000 years ago,[47][48][49][50] only a small group, possibly as few as 150 to 1,000 people, crossed the Red Sea.[51] The group that crossed the Red Sea travelled along the coastal route around the coast of Arabia and Persia until reaching India, which appears to be the first major settling point.[52] Geneticist Spencer Wells says that the early travellers followed the southern coastline of Asia, crossed about 250 kilometres (155 mi) of sea, and colonized Australia by around 50,000 years ago. The Aborigines of Australia, Wells says, are the descendants of the first wave of migrations.[53]

The oldest definitively identified Homo sapiens fossils yet found in South Asia are Balangoda man. Named for the location in Sri Lanka where they were discovered, they are at least 28,000 years old.[54]

Hypothised substrates

"Negritos"

The appropriateness of using the label 'Negrito' to bundle together peoples of different ethnicity based on similarities in stature and complexion has been challenged.[55] The Negrito peoples are more likely descended from the Melanesian-related settlers of Southeast Asia. Vishwanathan et al. (2004) conclude that "the tribal groups of southern India share a common ancestry, regardless of phenotypic characteristics, and are more closely related to other Indian groups than to African groups."[56] According to Vishwanathan et al. (2004), the typical "negrito" features could also have been developed by convergent evolution.[56] According to Gyaneshwer Chaubey and Endicott (2013), "At the current level of genetic resolution, however, there is no evidence of a single ancestral population for the different groups traditionally defined as 'negritos."[57]

According to Reich et al. (2009), "ASI, Proto-East-Asians and Andaman islanders" split around 1,700 generations ago. And the Andaman Islanders, though distinct from it, are the closest surviving group to the "ASI" population which contributed varying degrees of ancestry to South Asians.[58][note 5] According to Chaubey and Endicott (2013) Overall, the Andamanese are more closely related to Southeast Asians than they are to present-day South Asians.[57][note 6]

Modern South Asians have not been found to carry the paternal lineages common in the Andamanese, which has been suggested to indicate that certain lineages may have become extinct in India or that they may be very rare and have not yet been sampled.[59]

According to a large craniometric study (Raghavan and Bulbeck et al. 2013) the native populations of South Asia (India and Sri Lanka) have distinct craniometric and anthropologic ancestry. Both southern and northern groups are most similar to each other and have generally closer affinities to various "Caucasoid" groups. The study further showed that the native South Asians (including the Vedda) form a distinct group and are not morphologically aligned to "Australoid" or "Negrito" groups. The authors state: "If there were an Australoid “substratum” component to Indians’ ancestry, we would expect some degree of craniometric similarity between Howells’ Southwest Pacific series and Indians. But in fact, the Southwest Pacific and Indian are craniometrically very distinct, falsifying any claim for an Australoid substratum in India."

However, Raghavan and Bulbeck et al., while noting the distinctiveness between South Asian and Andamanese crania, also explain that this is not in conflict with genetic evidence (found by Reich et al. in 2009), which suggests some shared ancestry between Andamanese and South Asians.[60]

Moorjani et al. 2013 state that the ASI, though not closely related to any living group, are "related (distantly) to indigenous Andaman Islanders." Moorjani et al. also suggest possible gene flow into the Andamanese from a population related to the ASI. The study concluded that “almost all groups speaking Indo-European or Dravidian languages lie along a gradient of varying relatedness to West Eurasians in PCA (referred to as “Indian cline”)”.[61]

Basu et al. 2016 concluded that the Andamanese have a distinct ancestry and are not closely related to other South Asians but are closer to Southeast Asian Negritos, indicating that South Asian peoples do not descend directly from "Negritos" as such.[33]

A study by Narasimhan et al. in 2018 observed that samples from an "Indus periphery group" (a population from the periphery of the Indus Valley civilization) are always mixes of Andamanese-related South Asian hunter-gatherer ancestry (called "AASI") and Iranian agriculturalist-related ancestry; with "one of the Indus Periphery individuals having ~42% AASI ancestry and the other two individuals having ~14-18% AASI ancestry".[34]

A genetic study by Yelmen et al. 2019 shows that the native South Asian genetic component (ASI) is distinct from the Andamanese and not closely related, and that the Andamanese are thus an imperfect and imprecise proxy for ASI. According to Yelmen et al, the Andamanese component (represented by the Andamanese Onge) was not detected in the northern Indian Gujarati, and thus it is suggested that the South Indian tribal Paniya people (who are believed to be of largely ASI ancestry) would serve as a better proxy than the Andamanese (Onge) for the "native South Asian" component in modern South Asians.[62]

Genetic studies by Shinde et al. and Narasimhan et al. (both in 2019) on remains from the Indus Valley civilization of northeast India and nearby Pakistan, found a mixture of two kinds of ancestry: ancestry from native South Asian hunter-gatherers distantly related to the Andamanese (ranging from 2% to 50%) and early Iranian farmer-related ancestry (50% to 98%) in those analyzed by Shinde et al. (with the Iranian farmer related ancestry generally greater), and with the samples analyzed by Narasimhan et al. having 45–82% Iranian farmer-related ancestry and 11–50% AASI (or Andamanese-related hunter-gatherer ancestry).[36][37]

Vedda

Groups ancestral to the modern Veddas were probably the earliest inhabitants of the area. Their arrival is dated tentatively to 60,000–70,000 years ago. They are genetically distinguishable from the other peoples of Sri Lanka and they show a high degree of intra-group diversity. This is consistent with a long history of existing as small subgroups undergoing significant genetic drift.[63][64]

Holocene

After the last glacial maximum, human populations started to grow and migrate. With the invention of agriculture, the so-called Neolithic revolution, larger numbers of people could be sustained. The use of metals (copper, bronze, iron) further changed human ways of life, giving an initial advance to early users, and aiding further migrations, and admixture.

Neolithic period

According to Gallego Romero et al. (2011), their research on lactose tolerance in India suggests that "the west Eurasian genetic contribution identified by Reich et al. (2009) principally reflects gene flow from Iran and the Middle East."[65] Gallego Romero notes that Indians who are lactose-tolerant show a genetic pattern regarding this tolerance which is "characteristic of the common European mutation."[26] According to Romero, this suggests that "the most common lactose tolerance mutation made a two-way migration out of the Middle East less than 10,000 years ago. While the mutation spread across Europe, another explorer must have brought the mutation eastward to India – likely traveling along the coast of the Persian Gulf where other pockets of the same mutation have been found."[26]

Asko Parpola, who regards the Harappans to have been Dravidian, notes that Mehrgarh (7000 BCE to c. 2500 BCE), to the west of the Indus River valley,[66] is a precursor of the Indus Valley Civilisation, whose inhabitants migrated into the Indus Valley and became the Indus Valley Civilisation.[67] It is one of the earliest sites with evidence of farming and herding in South Asia.[68][69] According to Lukacs and Hemphill, while there is a strong continuity between the neolithic and chalcolithic (Copper Age) cultures of Mehrgarh, dental evidence shows that the chalcolithic population did not descend from the neolithic population of Mehrgarh,[70] which "suggests moderate levels of gene flow."[70] They further noted that "the direct lineal descendents of the Neolithic inhabitants of Mehrgarh are to be found to the south and the east of Mehrgarh, in northwestern India and the western edge of the Deccan plateau," with neolithic Mehrgarh showing greater affinity with chalcolithic Inamgaon, south of Mehrgarh, than with chalcolithic Mehrgarh.[70]

According to David McAlpin, the Dravidian languages were brought to India by immigration into India from Elam.[71][72][73][74] According to Renfrew and Cavalli-Sforza, proto-Dravidian was brought to India by farmers from the Iranian part of the Fertile Crescent,[75][76][77][note 7] but more recently Heggerty and Renfrew noted that "McAlpin's analysis of the language data, and thus his claims, remain far from orthodoxy", adding that Fuller finds no relation of Dravidian language with other languages, and thus assumes it to be native to India.[78] Renfrew and Bahn conclude that several scenarios are compatible with the data, and that "the linguistic jury is still very much out."[78][note 8]

Narasimhan et al. (2018) conclude that ANI and ASI were formed in the 2nd millennium BCE.[34], and were preceded by a mixture of “AASI” (ancient ancestral South Asian hunter-gatherers, sharing a common origin with the Andamanese), and early peoples from what is now Iran, who arrived in India ca. 4700–3000 BCE.[34] Narasimhan et al. observe that samples from the Indus periphery population are always mixes of the same two proximal sources of AASI and Iranian agriculturalist-related ancestry; with "one of the Indus Periphery individuals having ~42% AASI ancestry and the other two individuals having ~14-18% AASI ancestry" (with the remainder of their ancestry being from the Iranian agriculturalist-related population).[34]

The Iranian farmer-related ancestry in the Indus Valley Civilisation is estimated at 50-98% according to a 2019 study by Shinde et al. (generally a majority) and at 45–82% according to a 2019 study by Narasimhan et al., with the remainder in both studies (2-50% according to Shinde et al, and 11–50% according to Narasimhan et al.) deriving from the "AASI" population (native South Asian hunter-gatherers sharing a common root with the indigenous Andamanese).[36][37]

Austroasiatic

According to Ness, there are three broad theories on the origins of the Austroasiatic speakers, namely northeastern India, central or southern China, or southeast Asia.[85] Multiple researches indicate that the Austroasiatic populations in India are derived from (mostly male dominated) migrations from southeast Asia during the Holocene.[86][87][88][89][90][note 9] According to Van Driem (2007),

...the mitochondrial picture indicates that the Munda maternal lineage derives from the earliest human settlers on the Subcontinent, whilst the predominant Y chromosome haplogroup argues for a Southeast Asian paternal homeland for Austroasiatic language communities in India.[91]

According to Chaubey et al. (2011), "AA speakers in India today are derived from dispersal from Southeast Asia, followed by extensive sex-specific admixture with local Indian populations."[87][note 10] According to Zhang et al. (2015), Austroasiatic (male) migrations from southeast Asia into India took place after the lates Glacial maximum, circa 10,000 years ago.[89] According to Arunkumar et al. (2015), Y-chromosomal haplogroup O2a1-M95, which is typical for Austrosiatic speaking peoples, clearly decreases from Laos to east India, with "a serial decrease in expansion time from east to west," namely "5.7 ± 0.3 Kya in Laos, 5.2 ± 0.6 in Northeast India, and 4.3 ± 0.2 in East India." This suggests "a late Neolithic east to west spread of the lineage O2a1-M95 from Laos."[90][92]

According to Riccio et al. (2011), the Munda people are likely descended from Austroasiatic migrants from southeast Asia.[88][93] According to Ness, the Khasi probably migrated into India in the first millennium BCE.[85]

According to a genetic research (2015) including linguistic analyses, suggests an East Asian origin for proto-Austroasiatic groups, which first migrated to Southeast Asia and later into India.[94]

Indo-Aryans

* The magenta area corresponds to the assumed Urheimat (Samara culture, Sredny Stog culture) and the subsequent Yamna culture.

* The red area corresponds to the area which may have been settled by Indo-European-speaking peoples up to c. 2500 BCE.

* The orange area to 1000 BCE.[95]

The Indo-Aryan migration theory[note 11] explains the introduction of the Indo-Aryan languages in the Indian subcontinent by proposing migrations from the Sintashta culture[97][98] through Bactria-Margiana Culture and into the northern Indian subcontinent (modern day India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nepal). It is based on linguistic similarities between northern Indian and western European languages, and supported by archeological and anthropological research. They form part of a complex genetical puzzle on the origin and spread of the various components of the Indian population.

The Indo-Aryan migrations started in approximately 1,800 BCE, after the invention of the war chariot, and also brought Indo-Aryan languages into the Levant and possibly Inner Asia. It was part of the diffusion of Indo-European languages from the proto-Indo-European homeland at the Pontic steppe, a large area of grasslands in far Eastern Europe, which started in the 5th to 4th millennia BCE, and the Indo-European migrations out of the Eurasian steppes, which started approximately in 2,000 BCE.[99][96]

The theory posits that these Indo-Aryan speaking people may have been a genetically diverse group of people who were united by shared cultural norms and language, referred to as aryā, "noble." Diffusion of this culture and language took place by patron-client systems, which allowed for the absorption and acculturalisation of other groups into this culture, and explains the strong influence on other cultures with which it interacted.

The idea of an Indo-Aryan immigration was developed shortly after the discovery of the Indo-European language family in the late 18th century, when similarities between western and Indian languages had been noted. Given these similarities, a single source or origin was proposed, which was diffused by migrations from some original homeland. This linguistic argument[100] is complemented with archaeological, literary, and cultural evidence, and research and discussions on it continue.

The Proto-Indo-Iranians, from which the Indo-Aryans developed, are identified with the Sintashta culture (2100–1800 BCE),[101] and the Andronovo culture,[102] which flourished ca. 1800–1400 BCE in the steppes around the Aral sea, present-day Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. The proto-Indo-Iranians were influenced by the Bactria-Margiana Culture, south of the Andronovo culture, from which they borrowed their distinctive religious beliefs and practices. The Indo-Aryans split off around 1800–1600 BCE from the Iranians,[103] whereafter the Indo-Aryans migrated into the Levant and north-western India.

Tibeto-Burmese

According to Cordaux et al. (2004), the Tibeto-Burmans possibly came from the Himalayan and north-eastern borders of the subcontinent within the past 4,200 years.[104]

A wide variety of Tibeto-Burman languages are spoken on the southern slopes of the Himalayas. Sizable groups that have been identified are the West Himalayish languages of Himachal Pradesh and western Nepal, the Tamangic languages of western Nepal, including Tamang with one million speakers, and the Kiranti languages of eastern Nepal. The remaining groups are small, with several isolates.

The Newar language (Nepal Bhasa) of central Nepal has a million speakers and a literature dating from the 12th century, and nearly a million people speak Magaric languages, but the rest have small speech communities. Other isolates and small groups in Nepal are Dura, Raji–Raute, Chepangic and Dhimalish. Lepcha is spoken in an area from eastern Nepal to western Bhutan.[105] Most of the languages of Bhutan are Bodish, but it also has three small isolates, 'Ole ("Black Mountain Monpa"), Lhokpu and Gongduk and a larger community of speakers of Tshangla.[106]

Crossovers in languages and ethnicity

One complication in studying various population groups is that ethnic origins and linguistic affiliations in India match only inexactly: while the Oraon adivasis are classified as an "Austric" group, their language, called Kurukh, is Dravidian.[107] The Nicobarese are considered to be a Mongoloid group,[108][109] and the Munda and Santals Adivasi are "Austric" groups,[110][111][112] but all four speak Austro-Asiatic languages.[108][109][110] The Bhils and Gonds Adivasi are frequently classified as "Austric" groups,[113] yet Bhil languages are Indo-European and the Gondi language is Dravidian.[107]

See also

Notes

- ^ Basu et al. (2016) discern four major ancestries in mainland India, namely ANI, ASI, Ancestral Austro-Asiatic tribals (AAA) and Ancestral Tibeto-Burman (ATB).[5]

- ^ Basu et al. (2016): "By sampling populations, especially the autochthonous tribal populations, which represent the geographical, ethnic, and linguistic diversity of India, we have inferred that at least four distinct ancestral components—not two, as estimated earlier have contributed to the gene pools of extant populations of mainland India."[9]

- ^ Basu et al. (2016) discern four major ancestries in mainland India, namely ANI, ASI, Ancestral Austro-Asiatic tribals (AAA) and Ancestral Tibeto-Burman (ATB).[5]

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Dravidianwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ According to Basu et al. (2016): "The Andaman archipelago was peopled by members of a distinct, fifth ancestry,"[9] yet they also state that "ADMIXTURE analysis with K = 3 shows ASI plus AAA to be a single population."[9]

- ^ Chaubey and Endicott (2013):[57]

* "these estimates suggest that the Andamans were settled less than ~26 ka and that differentiation between the ancestors of the Onge and Great Andamanese commenced in the Terminal Pleistocene." (p.167)

* "In conclusion, we find no support for the settlement of the Andaman Islands by a population descending from the initial out-of-Africa migration of humans, or their immediate descendants in South Asia. It is clear that, overall, the Onge are more closely related to Southeast Asians than they are to present-day South Asians." (p.167) - ^ Derenko: "The spread of these new technologies has been associated with the dispersal of Dravidian and Indo-European languages in southern Asia. It is hypothesized that the proto-Elamo-Dravidian language, most likely originated in the Elam province in southwestern Iran, spread eastwards with the movement of farmers to the Indus Valley and the Indian sub-continent."[77]

Derenko refers to:

* Renfrew (1987), Archaeology and Language: The Puzzle of Indo-European Origins

* Renfrew (1996), Language families and the spread of farming. In: Harris DR, editor, The origins and spread of Agriculture and Pastoralism in Eurasia, pp. 70–92

* Cavalli-Sforza, Menozzi, Piazza (1994), The History and Geography of Human Genes. - ^ The Elamite-hypothesis has drawn attention in the scholarly literature, but has never been fully accpeted:

* According to Mikhail Andronov, Dravidian languages were brought to India at the beginning of the third millennium BCE.[79]

* Kivisild et al. (1999) note that "a small fraction of the West Eurasian mtDNA lineages found in Indian populations can be ascribed to a relatively recent admixture."[80] at ca. 9,300 ± 3,000 years before present,[81] which coincides with "the arrival to India of cereals domesticated in the Fertile Crescent" and "lends credence to the suggested linguistic connection between the Elamite and Dravidic populations."[81]

* According to Palanichamy et al. (2015), "The presence of mtDNA haplogroups (HV14 and U1a) and Y-chromosome haplogroup (L1) in Dravidian populations indicates the spread of the Dravidian language into India from west Asia."[82]

According to Krishnamurti, Proto-Dravidian may have been spoken in the Indus civilization, suggesting a "tentative date of Proto-Dravidian around the early part of the third millennium."[83] Krishnamurti further states that South Dravidian I (including pre-Tamil) and South Dravidian II (including Pre-Telugu) split around the eleventh century BCE, with the other major branches splitting off at around the same time.[84] - ^ Nevertheless, according to Basu et al. (2016), the AAA were early settlers in India, related to the ASI: "The absence of significant resemblance with any of the neighboring populations is indicative of the ASI and the AAA being early settlers in India, possibly arriving on the “southern exit” wave out of Africa. Differentiation between the ASI and the AAA possibly took place after their arrival in India (ADMIXTURE analysis with K = 3 shows ASI plus AAA to be a single population in SI Appendix, Fig. S2).[9]

- ^ See also:

* "Origin of Indian Austroasiatic speakers". Dienekes Anthropology Blog. 27 October 2010.

* Khan, Razib (2010). "Sons of the conquerors: the story of India?".{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)

* Khan, Razib (2013). "Phylogenetics implies Austro-Asiatic are intrusive to India".{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ The term "invasion" is only being used nowadays by opponents of the Indo-Aryan Migration theory.[96] The term "invasion" does not reflect the contemporary scholarly understanding of the Indo-Aryan migrations,[96] and is merely being used in a polemical and distractive way.

References

- ^ "Migrant Nation".

- ^ a b c d e f g h Reich et al. 2009.

- ^ a b Metspalu et al. 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g Moorjani et al. 2013.

- ^ a b Basu et al. 2016, p. 1594.

- ^ a b c d Narashimhan et al. 2019. Cite error: The named reference "FOOTNOTENarashimhan et al.2019" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Yelmen et al. 2019.

- ^ a b c Shinde et al. 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Basu 2016, p. 1598.

- ^ Chaubey (2015). "East Asian ancestry in India".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Brucato, Nicolas; Fernandes, Veronica; Kusuma, Pradiptajati; Černý, Viktor; Mulligan, Connie J.; Soares, Pedro; Rito, Teresa; Besse, Céline; Boland, Anne; Deleuze, Jean-Francois; Cox, Murray P. (1 March 2019). "Evidence of Austronesian Genetic Lineages in East Africa and South Arabia: Complex Dispersal from Madagascar and Southeast Asia". Genome Biology and Evolution. 11 (3): 748–758. doi:10.1093/gbe/evz028.

- ^ Yunusbayev, Bayazit; Metspalu, Mait; Metspalu, Ene; Valeev, Albert; Litvinov, Sergei; Valiev, Ruslan; Akhmetova, Vita; Balanovska, Elena; Balanovsky, Oleg; Turdikulova, Shahlo; Dalimova, Dilbar (21 April 2015). "The Genetic Legacy of the Expansion of Turkic-Speaking Nomads across Eurasia". PLoS Genetics. 11 (4). doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005068. ISSN 1553-7390. PMC 4405460. PMID 25898006.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Narashimhan et al. 2019, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e Narashimhan et al 2018.

- ^ Narashimhan et al 2019.

- ^ a b Shinde et al 2019.

- ^ Lazaridis, Iosif (2016), "The genetic structure of the world's first farmers", bioRxiv 059311

{{cite bioRxiv}}: Check|biorxiv=value (help) - ^ Chaubey (2015). "East Asian ancestry in India".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Yunusbayev, Bayazit; Metspalu, Mait; Metspalu, Ene; Valeev, Albert; Litvinov, Sergei; Valiev, Ruslan; Akhmetova, Vita; Balanovska, Elena; Balanovsky, Oleg; Turdikulova, Shahlo; Dalimova, Dilbar (21 April 2015). "The Genetic Legacy of the Expansion of Turkic-Speaking Nomads across Eurasia". PLoS Genetics. 11 (4). doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005068. ISSN 1553-7390. PMC 4405460. PMID 25898006.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Brucato, Nicolas; Fernandes, Veronica; Kusuma, Pradiptajati; Černý, Viktor; Mulligan, Connie J.; Soares, Pedro; Rito, Teresa; Besse, Céline; Boland, Anne; Deleuze, Jean-Francois; Cox, Murray P. (1 March 2019). "Evidence of Austronesian Genetic Lineages in East Africa and South Arabia: Complex Dispersal from Madagascar and Southeast Asia". Genome Biology and Evolution. 11 (3): 748–758. doi:10.1093/gbe/evz028.

- ^ Chaubey (2015). "East Asian ancestry in India".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Basu et al. 2016, p. 1598.

- ^ Moorjani et al. 2013, p. 422-423.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Reich-interviewwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Gallego Romero 2011, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d Mitchum, Rob (14 September 2011). "Lactose Tolerance in the Indian Dairyland". ScienceLife. UChicago Medicine.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Lazaridis et al. 2016.

- ^ a b Kivisild et al. 1999.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Kivisild2000was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Jones 2015.

- ^ a b Basu et al. 2016.

- ^ Basu 2016.

- ^ a b Basu 2016, p. 1594.

- ^ a b c d e f g Narasimhan et al. 2018, p. 15.

- ^ Yelmen, Burak; Mondal, Mayukh; Marnetto, Davide; Pathak, Ajai K.; Montinaro, Francesco; Gallego Romero, Irene; Kivisild, Toomas; Metspalu, Mait; Pagani, Luca (1 August 2019). "Ancestry-Specific Analyses Reveal Differential Demographic Histories and Opposite Selective Pressures in Modern South Asian Populations". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 36 (8): 1628–1642. doi:10.1093/molbev/msz037. ISSN 0737-4038. PMC 6657728. PMID 30952160.

- ^ a b c Shinde V, Narasimhan VM, Rohland N, Mallick S, Mah M, Lipson M, et al. (October 2019). "An Ancient Harappan Genome Lacks Ancestry from Steppe Pastoralists or Iranian Farmers". Cell. 179 (3): 729–735.e10. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2019.08.048. PMC 6800651. PMID 31495572.

- ^ a b c Narasimhan VM, Patterson N, Moorjani P, Rohland N, Bernardos R, Mallick S, et al. (September 2019). "The formation of human populations in South and Central Asia". Science. 365 (6457): eaat7487. doi:10.1126/science.aat7487. PMC 6822619. PMID 31488661.

- ^ a b c Appenzeller 2015.

- ^ a b "Supervolcano Eruption – In Sumatra – Deforested India 73,000 Years Ago". ScienceDaily. 24 November 2009. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

... new study provides "incontrovertible evidence" that the volcanic super-eruption of Toba on the island of Sumatra about 73,000 years ago deforested much of central India, some 3,000 miles from the epicenter ... initiating an "Instant Ice Age" that – according to evidence in ice cores taken in Greenland – lasted about 1,800 years ...

- ^ Oppenheimer Chaudhuri, Stephen (2004). Out of Eden: the peopling of the world. Robinson. ISBN 978-1-84119-894-1.

... The Toba event specifically blanketed the Indian subcontinent in a deep layer of ash. It is difficult to see how India's first colonists could have survived this greatest of all disasters. So, we could predict a broad human extinction ...

- ^ Petraglia, Michael D.; Allchin, Bridget (22 May 2007). The evolution and history of human populations in South Asia: Inter-disciplinary Studies in Archaeology, Biological Anthropology, Linguistics and Genetics. Springer, 2007. ISBN 978-1-4020-5561-4.

... had H. sapiens colonized India before the eruption? The majority of genetic evidence seems to suggest that the initial colonization of India took place soon after the Toba event. It should be noted, however, that on the basis of this evidence, the hypothesis that modern human populations inhabited India before ~74ka and underwent extinction as a result of Toba cannot be ruled out. If population extinction occurred, there would be no trace of their DNA in present-day humans ...

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "New evidence shows populations survived the Toba super-eruption 74,000 years ago". University of Oxford. 22 February 2009. Archived from the original on 30 December 2010. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

... Newly discovered archaeological sites in southern and northern India have revealed how people lived before and after the colossal Toba volcanic eruption 74,000 years ago. The international, multidisciplinary research team, led by Oxford University in collaboration with Indian institutions, has uncovered what it calls 'Pompeii-like excavations' beneath the Toba ash ... suggests that human populations were present in India prior to 74,000 years ago, or about 15,000 years earlier than expected based on some genetic clocks,' said project director Dr Michael Petraglia ...

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Macauly 2005.

- ^ a b Bradshaw Foundation, Human Migration

- ^ Posth 2016.

- ^ Kennedy KA, Sonakia A, Chiment J, Verma KK (December 1991). "Is the Narmada hominid an Indian Homo erectus?". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 86 (4): 475–96. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330860404. PMID 1776655.

- ^ Hirst, K. Kris. "Southern Dispersal Route – Early Modern Humans Leave Africa". About.com.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Posth C, Renaud G, Mittnik A, Drucker DG, Rougier H, Cupillard C, et al. (March 2016). "Pleistocene Mitochondrial Genomes Suggest a Single Major Dispersal of Non-Africans and a Late Glacial Population Turnover in Europe". Current Biology. 26 (6): 827–33. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.01.037. PMID 26853362.

- ^ Karmin M, Saag L, Vicente M, Wilson Sayres MA, Järve M, Talas UG, et al. (April 2015). "A recent bottleneck of Y chromosome diversity coincides with a global change in culture". Genome Research. 25 (4): 459–66. doi:10.1101/gr.186684.114. PMC 4381518. PMID 25770088.

- ^ Haber M, Jones AL, Connell BA, Arciero E, Yang H, Thomas MG, et al. (August 2019). "A Rare Deep-Rooting D0 African Y-Chromosomal Haplogroup and Its Implications for the Expansion of Modern Humans Out of Africa". Genetics. 212 (4): 1421–1428. doi:10.1534/genetics.119.302368. PMC 6707464. PMID 31196864.

- ^ Stix, Gary (2008). "The Migration History of Humans: DNA Study Traces Human Origins Across the Continents". Retrieved 14 June 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Metspalu M, Kivisild T, Metspalu E, Parik J, Hudjashov G, Kaldma K, et al. (August 2004). "Most of the extant mtDNA boundaries in south and southwest Asia were likely shaped during the initial settlement of Eurasia by anatomically modern humans". BMC Genetics. 5: 26. doi:10.1186/1471-2156-5-26. PMC 516768. PMID 15339343.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Rincon, Paul (24 April 2008). "Human line 'nearly split in two'". BBC News. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Deraniyagala, Siran U. (1 June 1989). "Fossil Remains of 28,000-Year-Old Hominids from Sri Lanka". Current Anthropology. 30 (3): 394–399. doi:10.1086/203757. ISSN 0011-3204.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Manickham 2009.

- ^ a b Vishwanathan 2004.

- ^ a b c Chaubey G, Endicott P (2013). "The Andaman Islanders in a regional genetic context: reexamining the evidence for an early peopling of the archipelago from South Asia". Human Biology. 85 (1–3): 153–72. doi:10.3378/027.085.0307. PMID 24297224.

- ^ Reich 2009a, p. 40.

- ^ Endicott P, Gilbert MT, Stringer C, Lalueza-Fox C, Willerslev E, Hansen AJ, Cooper A (January 2003). "The genetic origins of the Andaman Islanders". American Journal of Human Genetics. 72 (1): 178–84. doi:10.1086/345487. PMC 378623. PMID 12478481.

- ^ Raghavan P, Bulbeck D, Pathmanathan G, Rathee SK (2013). "Indian craniometric variability and affinities". International Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 2013: 836738. doi:10.1155/2013/836738. PMC 3886603. PMID 24455409.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Moorjani P, Thangaraj K, Patterson N, Lipson M, Loh PR, Govindaraj P, et al. (September 2013). "Genetic evidence for recent population mixture in India". American Journal of Human Genetics. 93 (3): 422–38. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.07.006. PMC 3769933. PMID 23932107.

- ^ Yelmen, Burak; Mondal, Mayukh; Marnetto, Davide; Pathak, Ajai K.; Montinaro, Francesco; Gallego Romero, Irene; Kivisild, Toomas; Metspalu, Mait; Pagani, Luca (1 August 2019). "Ancestry-Specific Analyses Reveal Differential Demographic Histories and Opposite Selective Pressures in Modern South Asian Populations". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 36 (8): 1628–1642. doi:10.1093/molbev/msz037. ISSN 0737-4038. PMC 6657728. PMID 30952160.

- ^ Deraniyagala SU (September 1996). "Pre-and protohistoric settlement in Sri Lanka". XIII UISPP Congress Proceedings. 5: 277–285.

- ^ Ranaweera L, Kaewsutthi S, Win Tun A, Boonyarit H, Poolsuwan S, Lertrit P (January 2014). "Mitochondrial DNA history of Sri Lankan ethnic people: their relations within the island and with the Indian subcontinental populations". Journal of Human Genetics. 59 (1): 28–36. doi:10.1038/jhg.2013.112. PMID 24196378.

- ^ Gallego Romero & 202011, p. 9.

- ^ "Stone age man used dentist drill". BBC News. 6 April 2006.

- ^ Parpola 2015, p. 17.

- ^ "Archaeological Site of Mehrgarh". UNESCO World Heritage. 2004.

- ^ Hirst, K. Kris (2005). "Mehrgarh". Guide to Archaeology.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Coningham & Young 2015, p. 114.

- ^ McAlpin D, Emeneau MB, Jacobsen Jr WH, Kuiper FB, Paper HH, Reiner E, Stopa R, Vallat F, Wescott RW (March 1975). "Elamite and Dravidian: Further Evidence of Relationship [and Comments and Reply].". Current Anthropology. Vol. 16. pp. 105–15.

- ^ McAlpin DW (1979). "Linguistic prehistory: the Dravidian situation.". Aryan and Non-Aryan. Ann Arbor: Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies, University of Michigan. pp. 175–89.

- ^ McAlpin DW (January 1981). "Proto-Elamo-Dravidian: The evidence and its implications". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 71 (3): 1–55. doi:10.2307/1006352. JSTOR 1006352.

- ^ Kumar, Dhavendra (2004). Genetic Disorders of the Indian Subcontinent. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-1215-0. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

... The analysis of two Y chromosome variants, Hgr9 and Hgr3 provides interesting data (Quintan-Murci et al., 2001). Microsatellite variation of Hgr9 among Iranians, Pakistanis and Indians indicate an expansion of populations to around 9000 YBP in Iran and then to 6,000 YBP in India. This migration originated in what was historically termed Elam in south-west Iran to the Indus valley, and may have been associated with the spread of Dravidian languages from south-west Iran (Quintan-Murci et al., 2001). ...

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Cavalli-Sforza 1994, p. 221-222.

- ^ Mukherjee N, Nebel A, Oppenheim A, Majumder PP (December 2001). "High-resolution analysis of Y-chromosomal polymorphisms reveals signatures of population movements from Central Asia and West Asia into India". Journal of Genetics. 80 (3): 125–35. doi:10.1007/bf02717908. PMID 11988631.

... More recently, about 15,000-10,000 years before present (ybp), when agriculture developed in the Fertile Crescent region that extends from Israel through northern Syria to western Iran, there was another eastward wave of human migration (Cavalli-Sforza et al., 1994; Renfrew 1987), a part of which also appears to have entered India. This wave has been postulated to have brought the Dravidian languages into India (Renfrew 1987). Subsequently, the Indo-European (Aryan) language family was introduced into India about 4,000 ybp ...

- ^ a b Derenko 2013.

- ^ a b Heggarty, Paul; Renfrew, Collin (2014). "South and Island Southeast Asia; Languages". In Renfrew, Colin; Bahn, Paul (eds.). The Cambridge World Prehistory. Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Andronov 2003, p. 299.

- ^ Kivisild 1999, p. 1331.

- ^ a b Kivisild 1999, p. 1333.

- ^ Palanichamy (2015), p. 645.

- ^ Krishnamurti 2003, p. 501.

- ^ Krishnamurti 2003, p. 501-502.

- ^ a b Ness 2014, p. 265. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFNess2014 (help)

- ^ van Driem 2007a.

- ^ a b Chaubey 2010.

- ^ a b Riccio ME, Nunes JM, Rahal M, Kervaire B, Tiercy JM, Sanchez-Mazas A (June 2011). "The Austroasiatic Munda population from India and Its enigmatic origin: a HLA diversity study". Human Biology. 83 (3): 405–35. doi:10.3378/027.083.0306. PMID 21740156.

- ^ a b Zhang 2015.

- ^ a b Arunkumar 2015.

- ^ van Driem 2007a, p. 7.

- ^ Vilar, Miguel (2015). "DNA Reveals Unknown Ancient Migration Into India". National Geographic.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Gutman, Alejandro; Avanzati, Beatriz. "Austroasiatic Languages". The Language Gulper.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Zhang (2015). "Y-chromosome diversity suggests southern origin and Paleolithic backwave migration of Austro- Asiatic speakers from eastern Asia to the Indian subcontinent".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Beckwith 2009, p. 30.

- ^ a b c Witzel 2005, p. 348.

- ^ Anthony 2007, pp. 408–411.

- ^ Kuz'mina 2007, p. 222.

- ^ Beckwith 2009, p. 33.

- ^ Bryant 2001.

- ^ Anthony 2009, p. 390 (fig. 15.9), 405–411.

- ^ Anthony 2009, p. 49.

- ^ Anthony 2007, p. 408.

- ^ Cordaux R, Weiss G, Saha N, Stoneking M (August 2004). "The northeast Indian passageway: a barrier or corridor for human migrations?". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 21 (8): 1525–33. doi:10.1093/molbev/msh151. PMID 15128876. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

... Our coalescence analysis suggests that the expansion of Tibeto-Burman speakers to northeast India most likely took place within the past 4,200 years ...

- ^ van Driem (2007), p. 296.

- ^ van Driem (2011a).

- ^ a b Cummins, Jim; Corson, David (1999). Bilingual Education. Springer. ISBN 978-0792348061. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

... over one million speakers each: Bhili (Indo-Aryan) 4.5 million; Santali (Austric) 4.2 m; Gondi (Dravidian) 2.0 m; and Kurukh (Dravidian) 1.3 million ...

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Khongsdier R, Mukherjee N (October 2003). "Growth and nutritional status of Khasi boys in Northeast India relating to exogamous marriages and socioeconomic classes". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 122 (2): 162–70. doi:10.1002/ajpa.10305. PMID 12949836. Archived from the original on 5 January 2013. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

... The Khasis are one of the Indo-Mongoloid tribes in Northeast India. They speak the Monkhmer language, which belongs to the Austro-Asiatic group (Das, 1978) ...

- ^ a b Rath, Govinda Chandra (2006). Tribal Development in India: The Contemporary Debate. SAGE. ISBN 978-0761934233. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

... The Car Nicobarese are of Mongoloid stock ... The Nicobarese speak different languages of the Nicobarese group, which belongs to an Austro-Asiatic language sub-family ...

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Srivastava, Malini (2007). "The Sacred Complex of Munda Tribe" (PDF). Anthropologist. 9 (4): 327–330. doi:10.1080/09720073.2007.11891020. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

... Racially, they are proto-australoid and speak Mundari dialect of Austro-Asiatic ...

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Chaudhuri AB (1993). State Formation Among Tribals: A Quest for Santal Identity. Gyan Publishing House. ISBN 978-8121204224. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

... The Santal is a large Proto-Australoid tribe found in West Bengal, northern Orissa, Bihar, Assam as also in Bangladesh ... The solidarity having been broken, the Santals are gradually adopting languages of the areas inhabited, like Oriya in Orissa, Hindi in Bihar and Bengali in West Bengal and Bangladesh ...

- ^ Chaudhuri AB (1949). "Tribal Heritage: A Study of the Santals". Lutterworth Press. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

... The Santals belong to his second "main race", the Proto-Australoid, which he considers arrived in India soon after the Negritos ...

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Shankarkumar U (2003). "A Correlative Study of HLA, Sickle Cell Gene and G6PD Deficiency with Splenomegaly and Malaria Incidence Among Bhils and Pawra Tribes from Dhadgon, Dhule, Maharastra" (PDF). Studies of Tribes and Tribals. 1 (2): 91–94. doi:10.1080/0972639X.2003.11886488. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

... The Bhils are one of the largest tribes concentrated mainly in Western Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Eastern Gujarat and Northern Maharastra. Racially they were classified as Gondids, Malids or Proto-Australoid, but their social history is still a mystery (Bhatia and Rao, 1986) ...

Sources

- Andronov, Mikhail Sergeevich (2003). A Comparative Grammar of the Dravidian Languages. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-04455-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Anthony, David W. (2007). "The Horse The Wheel And Language. How Bronze-Age Riders From the Eurasian Steppes Shaped The Modern World". Princeton University Press.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Appenzeller, Tim (2012). "Human migrations: Eastern odyssey. Humans had spread across Asia by 50,000 years ago. Everything else about our original exodus from Africa is up for debate". Nature. 485 (7396).

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Arunkumar G, Wei LH, Kavitha VJ, Syama A, Arun VS, Sathua S, Sahoo R, Balakrishnan R, Riba T, Chakravarthy J, Chaudhury B, et al. (The Genographic Consortium) (2015). "A late Neolithic expansion of Y chromosomal haplogroup O2a1-M95 from east to west". Journal of Systematics and Evolution. 53 (6): 546–560. doi:10.1111/jse.12147.

- Basu A, Sarkar-Roy N, Majumder PP (February 2016). "Genomic reconstruction of the history of extant populations of India reveals five distinct ancestral components and a complex structure". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 113 (6): 1594–9. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113.1594B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1513197113. PMC 4760789. PMID 26811443.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (16 March 2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-2994-1. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Bryant, Edwin (2001). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture: The Indo-Aryan Migration Debate. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513777-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help). - Cavalli-Sforza, Luigi Luca; Menozzi, Paolo; Piazza, Alberto (1994). "The History and Geography of Human Genes". Princeton University Press.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Chaubey G, Metspalu M, Choi Y, Mägi R, Romero IG, Soares P, et al. (February 2011). "Population genetic structure in Indian Austroasiatic speakers: the role of landscape barriers and sex-specific admixture". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 28 (2): 1013–24. doi:10.1093/molbev/msq288. PMC 3355372. PMID 20978040.

- Coningham, Robin; Young, Ruth (2015). "The Archaeology of South Asia: From the Indus to Asoka, c.6500 BCE–200 CE". Cambridge University Press.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Derenko M, Malyarchuk B, Bahmanimehr A, Denisova G, Perkova M, Farjadian S, Yepiskoposyan L (2013). "Complete mitochondrial DNA diversity in Iranians". PLOS ONE. 8 (11): e80673. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...880673D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080673. PMC 3828245. PMID 24244704.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - van Driem, George L. (2007). "South Asia and the Middle East". In Moseley, Christopher (ed.). Encyclopedia of the World's Endangered Languages. Routledge. pp. 283–347. ISBN 978-0-7007-1197-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - van Driem, George L. (2007b). "Austroasiatic phylogeny and the Austroasiatic homeland in light of recent population genetic studies" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - van Driem, George L. (2011a). "Tibeto-Burman subgroups and historical grammar". Himalayan Linguistics Journal. 10 (1): 31–39. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Kivisild T, Bamshad MJ, Kaldma K, Metspalu M, Metspalu E, Reidla M, et al. (November 1999). "Deep common ancestry of indian and western-Eurasian mitochondrial DNA lineages" (PDF). Current Biology. 9 (22): 1331–4. doi:10.1016/s0960-9822(00)80057-3. PMID 10574762. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2005.

- Kuz'mina, Elena Efimovna (2007). J. P. Mallory (ed.). The Origin of the Indo-Iranians. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-16054-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Manickham, Sandra Khor (2009). "Africans in Asia: The Discourse of 'Negritos' in Early Nineteenth-century Southeast Asia". In Hägerdal, Hans (ed.). Responding to the West: Essays on Colonial Domination and Asian Agency. Amsterdam University Press. pp. 69–79. ISBN 978-90-8964-093-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Metspalu M, Romero IG, Yunusbayev B, Chaubey G, Mallick CB, Hudjashov G, et al. (December 2011). "Shared and unique components of human population structure and genome-wide signals of positive selection in South Asia". American Journal of Human Genetics. 89 (6): 731–44. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.11.010. PMC 3234374. PMID 22152676.

- Moorjani P, Thangaraj K, Patterson N, Lipson M, Loh PR, Govindaraj P, et al. (September 2013). "Genetic evidence for recent population mixture in India". American Journal of Human Genetics. 93 (3): 422–38. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.07.006. PMC 3769933. PMID 23932107.

- Narasimhan, Vagheesh M.; Anthony, David; Mallory, James; Reich, David (2018). "The Genomic Formation of South and Central Asia". bioRxiv: 292581. doi:10.1101/292581.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Ness, Immanuel (2014). "The Global Prehistory of Human Migration". The Global Prehistory of Human Migration.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Palanichamy MG, Mitra B, Zhang CL, Debnath M, Li GM, Wang HW, et al. (June 2015). "West Eurasian mtDNA lineages in India: an insight into the spread of the Dravidian language and the origins of the caste system". Human Genetics. 134 (6): 637–47. doi:10.1007/s00439-015-1547-4. PMID 25832481.

- Posth C, Renaud G, Mittnik A, Drucker DG, Rougier H, Cupillard C, et al. (March 2016). "Pleistocene Mitochondrial Genomes Suggest a Single Major Dispersal of Non-Africans and a Late Glacial Population Turnover in Europe". Current Biology. 26 (6): 827–33. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.01.037. PMID 26853362.

- Ruhlen, Merritt (1991). A Guide to the World's Languages: Classification. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-1894-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Parpola, Asko (2010). "A Dravidian solution to the Indus script problem" (PDF). World Classical Tamil Conference.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Parpola, Asko (2015). "The Roots of Hinduism. The Early Arians and the Indus Civilization". Oxford University Press.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Reich D, Thangaraj K, Patterson N, Price AL, Singh L (September 2009). "Reconstructing Indian population history". Nature. 461 (7263): 489–94. Bibcode:2009Natur.461..489R. doi:10.1038/nature08365. PMC 2842210. PMID 19779445.

- Reich D, Thangaraj K, Patterson N, Price AL, Singh L (September 2009). "Reconstructing Indian population history" (PDF). Nature. 461 (7263): 489–94. Bibcode:2009Natur.461..489R. doi:10.1038/nature08365. PMC 2842210. PMID 19779445.

- Vishwanathan H, Deepa E, Cordaux R, Stoneking M, Usha Rani MV, Majumder PP (March 2004). "Genetic structure and affinities among tribal populations of southern India: a study of 24 autosomal DNA markers" (PDF). Annals of Human Genetics. 68 (Pt 2): 128–38. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2003.00083.x. PMID 15008792.

- Wells, Spencer (2002). The Journey of Man: A Genetic Odyssey. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-11532-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - * Wells, Spencer (2012). The Journey of Man: A Genetic Odyssey. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-691-11532-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Witzel, Michael (2005). "Indocentrism". In Bryant, Edwin; Patton, Laurie L. (eds.). TheE Indo-Aryan Controversy. Evidence and inference in Indian history. Routledge.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Zhang X, Liao S, Qi X, Liu J, Kampuansai J, Zhang H, et al. (October 2015). "Y-chromosome diversity suggests southern origin and Paleolithic backwave migration of Austro-Asiatic speakers from eastern Asia to the Indian subcontinent". Scientific Reports. 5: 15486. Bibcode:2015NatSR...515486Z. doi:10.1038/srep15486. PMC 4611482. PMID 26482917.

Further reading

- Ness, Immanuel (2014). "The Global Prehistory of Human Migration". The Global Prehistory of Human Migration.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)

External links

- Overview

- Negritos