David

David (Hebrew: דָּוִד, Standard Davíd Tiberian Dāwíð;Arabic: داوود or داود, Dā'ūd; Tigrinya:ዳዊት, Dāwīt), meaning "beloved", was the second king of the united Kingdom of Israel (c. 1011 BCE – 971 BCE). He succeeded Ish-bosheth, fourth son of King Saul. He is depicted as the most righteous of all the ancient kings of Israel - although not without fault - as well as an acclaimed warrior, musician and poet (he is traditionally credited with the authorship of many of the Psalms). In response to David's desire to build a House of God, God promised David that his royal house would endure forever.[1] Jews therefore believe that the Jewish Messiah will be a direct descendant of David, and Christians trace the lineage of Jesus back to him through both Mary and Joseph. The nature of his reign has been questioned and debated, rejected and defended by modern biblical scholars, but the account given in the Hebrew Bible remains widely accepted by the majority of ordinary Jews and Christians, and his story has been of central importance to Western culture. His life and rule are recorded in the Hebrew Bible's books of First Samuel (from chapter 16 onwards),[2] Second Samuel,[3] First Kings[4] and Second Kings (to verse 4).[5] First Chronicles[6] gives further stories of David, mingled with lists and genealogies.

Scriptural account of David's life

This section summarizes major episodes from David's life as recorded in the Hebrew Bible.

David is chosen

God had withdrawn his favor from King Saul and sent the prophet Samuel to Jesse of Bethlehem, "for I have provided for myself a king among his sons." The choice fell upon David, the youngest, who is guarding his father's sheep: "he was ruddy, and fine in appearance with handsome features. And the Lord said [to Samuel], 'Arise, anoint him; for this is he.'"

David and Goliath

The Israelites under Saul were facing the army of the Philistines. David, the youngest of the sons of Jesse, brought food each day to his brothers who were with Saul, and heard the Philistine champion, the giant Goliath, challenge the Israelites to send out their own champion to decide the outcome in single combat. David insisted to his brothers that he could defeat Goliath; Saul, upon hearing of this, sent for him, and although he was dubious, allowed him to go and make the attempt. David was indeed victorious, felling Goliath with a stone from his sling, at which the Philistines fled in terror and the Israelites won a great victory. David brought back the head of Goliath to Saul, who asks him whose son he is, and David told him, "I am the son of your servant Jesse the Bethlehemite".

Enmity of Saul

Saul requested that David bring him the foreskins of 100 Philistines upon which he would give him his daughter. When David brought back 200 foreskins, Saul gave David his second daughter Michal in marriage and set him in command over his armies, (literally, 'commander over a thousand'), and David was successful in many battles. David's popularity awakened Saul's fears - "What more can he have but the kingdom?" - and by various stratagems the king sought David's death. But the plots of the jealous king all proved futile, and only endeared the young hero the more to the people, and especially to Jonathan, Saul's son, who was one of those who loved David. Warned by Jonathan of Saul's enmity, David fled into the wilderness.

David is made king

An Amalekite soldier brought the news to David that king Saul and his son Jonathan had died. The young man claimed to have killed Saul himself, at the king's request, after Saul's attempt at suicide had failed. David had the Amalekite killed for having laid hands on the Lord's anointed king. He composed a song of lament for Saul and Jonathan, and ordered that it be taught to the men of Judah. David then went up to Hebron in Judah, where he was anointed King of Judah, while in the north Saul's son, Ish-bosheth was king over the Israel. There was a long war between the house of Saul and the house of David, and David grew stronger and stronger, while the house of Saul became weaker and weaker, until Ish-bosheth was assassinated. The assassins brought the head of Ish-bosheth to David hoping for reward, but he was angry that they had killed a righteous man, and executed them for their crime. Yet with the death of the son of Saul the elders of Israel came to Hebron, and David was anointed king of Israel, uniting the two kingdoms. Upon these events he was 30 years old.

God's promise to David

David conquers the Jebusite fortress of Jerusalem and makes it his capital, and brings the Ark of the Covenant there, intending to build a temple. But God, speaking to the prophet Nathan, forbids it, saying the temple must wait for a future generation, but that He will establish the house of David eternally: "Your throne shall be established for ever." Then David establishes a mighty empire, conquering Zobah and Aram (modern Syria), Edom and Moab (roughly modern Jordan), the lands of the Philistines, and much more.

Bathsheba and Uriah the Hittite

David, infatuated with the beautiful Bathsheba, has her brought to him at the palace and commits adultery with her. Bathsheba falls pregnant, and David sends for her husband, Uriah the Hittite, who is with the Israelite army at the siege of Rabbah, that he might lie with her and so conceal the identity of the child's father. But Uriah refuses to do so while his companions are in the field of battle. David then sends Uriah back to Joab the commander with a message instructing him to abandon Uriah on the battlefield, "that he may be struck down, and die." And so David marries Bathsheba and she bears his child, "but the thing that David had done displeased the Lord."[7] The prophet Nathan speaks out against David's sin, saying: "Why have you despised the word of the Lord, to do what is evil in his sight? You have smitten Uriah the Hittite with the sword, and have taken his wife to be your wife." And although David repents, God kills the child as a punishment. ("And the Lord struck the child ... and it became sick ... [And]On the seventh day the child died.") David then leaves his lamentations, dresses himself, and eats. His servants ask why he lamented when the baby was alive, but leaves off when it is dead, and David replies: "While the child was still alive, I fasted and wept; for I said, 'Who knows whether the Lord will be gracious to me, that the child may live?' But now he is dead, why should I fast? Can I bring him back again? I shall go to him, but he will not return to me."[8]

Absalom

David's beloved son Absalom rebels against his father. The armies of Absalom and David come to battle in the Wood of Ephraim, and Absalom is caught in the branches of an oak. David's general Joab kills him as he hangs there. When the news of the victory is brought to David he does not rejoice, but is instead shaken with grief: "O my son Absalom, my son, my son Absalom! Would I had died instead of you, O Absalom, my son, my son!"

Psalms authorship

David is described as the author of the majority of the Psalms of the Bible. One of the most famous is Psalm 51, traditionally said to have been composed by David after Nathan upbraided him: "To the choirmaster. A Psalm of David, when Nathan the prophet came to him, after he had gone in to Bathsheba." Perhaps the best-known is Psalm 23:

- 1 The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want.

- 2 He maketh me to lie down in green pastures:

- he leadeth me beside the still waters.

- 3 He restoreth my soul:

- he leadeth me in the paths of righteousness for his name's sake.

- 4 Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death,

- I will fear no evil: for thou art with me;

- thy rod and thy staff they comfort me.

- 5 Thou preparest a table before me in the presence of mine enemies:

- thou anointest my head with oil;

- my cup runneth over.

- 6 Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life:

- and I will dwell in the house of the LORD for ever."

Reign of David

"Thus David the son of Jesse reigned over all Israel. The time that he reigned over Israel was forty years; he reigned seven years in Hebron, and thirty-three years in Jerusalem. Then he died in a good old age, full of days, riches, and honor; and Solomon his son reigned in his stead."

David's family

David's father was Jesse, the son of Obed, son of Boaz of the tribe of Judah and Ruth the Moabite, whose story is told at length in the Book of Ruth. David's lineage is fully documented in Ruth 4:18–22, (the "Pharez" that heads the line is Judah's son, Genesis 38:29).

David had eight wives, although he appears to have had children from other women as well:

- Michal, the second daughter of King Saul

- Ahinoam of Jezreel

- Abigail, previously wife of the evil Nabal

- Maachah

- Haggith

- Abital

- Eglah

- Bathsheba, previously the wife of Uriah the Hittite

In his old age he took the beautiful Abishag into his bed for health reasons, "but the king knew her not (intimately)" (1 Kings 1:1–4).

As given in 1 Chronicles 3, David had sons by various wives and concubines; their names are not given in Chronicles. By Bathsheba, his sons were:

His sons born in Hebron by other mothers included:

- Amnon was the progeny of David and Ahinoam

- Daniel was the progeny of David and Abigail

- Absalom was the progeny of David and Maachah

- Adonijah was the progeny of David and Haggith

- Shephatiah was the progeny of David and Abital

- Ithream was the progeny of David and Eglah

His sons born in Jerusalem by other mothers included:

David also had at least one daughter, Tamar, progeny of David and Maachah and the full sister of Absalom.

Claimed descendants of David

A number of persons have claimed descent from the Biblical David, or had it claimed on their behalf. The following are some of the more notable:

- Jesus of Nazareth, (7-4 BCE, Bethlehem, Kafarnaum or Nazaret; † 30, 31 or 33, Jerusalem)

- Rabbi Akiba, Akiba ben Josef, also known as Akiva (b. c. 135)

- Judah Loew, Yehuda Loew ben Bezalel (c. 1525, Prague; 22 August 1609 Prague).

David as a religious figure

David in Judaism

In Judaism, David's reign represents the formation of a coherent Jewish kingdom with its political and religious capital in Jerusalem and the institution of a royal lineage that culminates in the Messianic Age. David's descent from a convert (Ruth) is taken as proof of the importance of converts within Judaism. That he was not allowed to build a permanent temple is taken as proof of the imperative of peace in affairs of state. David is also responsible for uniting the tribes of Israel as one people; before David they were a group of many tribes but David destroyed almost all separation of the individual tribes.

David is also viewed as a tragic figure; his inexcusable acquisition of Bathsheba, and the loss of his son are viewed as his central tragedies in Judaism.

The Talmud adamantly asserts that David committed no sin in his taking of Bathsheba. According to the Talmud, it was the custom of Israelite soldiers to leave their wives with a bill of divorce[verification needed], so as to avoid the possibility of a woman being unable to remarry if her husband went missing in action. For this reason, Bathsheba was legally unmarried at the time she was summoned to David, and there was no act of adultery. Furthermore, according to the Talmud, the death of Uriah is also not to be held against David.[citation needed] It was David's right as king to execute traitors to the throne, to which category Uriah belonged due to a technicality. David's only sin, then, was the improper and disgraceful manner in which he handled the whole affair.

David's sin is a fulfillment of God's own foretelling, through the judge Samuel, of what will happen to the nation if it forsakes God as their king and instead takes a man from among them to be king. Note the repeated use of "[the king] will take" in 1 Samuel 8 as a warning to Israel regarding the oppressive entitlements of a human king. Forgetting how God chose him from his humble beginnings by looking at his heart (1 Samuel 16) and having become blind to God's provision throughout his life, David has bought into that sense of royal entitlement. As God had warned, David has learned to consider himself free to take and to abuse his authority for personal gain. This is subsequently brought to light when David is confronted by the prophet Nathan (2 Samuel 11,12). Nathan causes David to identify his own sin through the metaphor of a wealthy man (David) who robs from his poor neighbor (Uriah). As king, David's sin is, for the entire nation, an embodiment of the discontinuity between being the covenant people of God who rely on his provision and then acting out of entitlement and selfish self-reliance. This is a lesson which Israel and its future kings will repeatedly ignore, important because doing so eventually leads to the demise of the kingdom.

David in Christianity

David's adaptation of the Jebusite Zion cult, "with its understanding of kingship as the ... presence of God on earth," led to Jerusalem's eventual status as the Jewish Holy City. Originally an earthly king ruling by divine appointment ("the anointed", as the title Messiah had it), the "son of David" became in the last two pre-Christian centuries the apocalyptic and heavenly "son of God" who would deliver Israel and usher in a new kingdom. "This was the matrix for the rise of Christianity. The new faith interpreted the career of Jesus by means of the titles and functions assigned to David in the mysticism of the Zion cult, in which he served as priest-king and in which he was the mediator between God and man."[9] Early Christians believed that the Hebrew scriptures prophesied that the Messiah would come from David's line, and the Gospels of Matthew and Luke therefore traced Jesus' lineage to David in fulfillment of this requirement. (See Davidic line). David later became figurative of Christ himself, the slaying of Goliath being compared to the way Jesus defeated Satan when he died on the cross, or of the Christian believer. In Christian thought, David is a type of Jesus - the rightful yet persecuted king of Israel, who after suffering as a fugitive ruled Israel in glory.[10](See typology).

The Roman Catholic Church celebrates his feast day on December 29.

David in Islam

David is one of the prophets of Islam, to whom the Zabur (Psalms) were revealed by God. Muslims reject the Biblical portrayal of David as an adulterer and murderer. This is based on the Islamic belief in the righteousness of prophets.

Goliath appears in the Qur'an as Jalut, which is Arabic for Goliath; and like Judaism, Goliath's slayer is David. In Surah Baqarah / Chapter 2, ayah 251, the text quotes: "And David slew Goliath, and God gave him kingdom and wisdom, and taught him of what He pleased." David was in Saul's (Arabic:Talut's) army. "Talut" is understood to be a rendering of David's predecessor Saul in such a way that it would rhyme with "Jalut"[citation needed].

David in Mormonism

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints originally cited David as an example in the Old Testament of polygamy. The Church forbade polygamy in 1890 and his significance is currently taught in terms familiar to traditional Christianity, as a righteous man brought low by failing to control his passions. [citation needed]

David in the Bahá'í Faith

In the Bahá'í faith, David is seen as a prophet during the dispensation of Moses, and Bahá'u'lláh, the Prophet-Founder of the Religion, is seen to be a descendent. [2]

Historicity of David

See The Bible and history and dating the Bible for a more complete description of the general issues surrounding the Bible as a historical source.

The Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) itself, being composed of no less than thirty-nine books traditionally written on twenty-four scrolls, is a library of many different sources. For that reason, researchers treat its accounts of past persons and events, as well as it references to them, as potentially valuable sources of historical data, but also as potentially flawed, exaggerated or mythical. The task of evaluating the historicity of David involves working between interpreted artifacts recovered in archeological digs and interpreted texts of biblical manuscripts received from tradition.

The most relevant biblical books are 1 and 2 Samuel, because they contain the earliest biblical account of almost David's entire career, followed in relevance by 1 and 2 Kings and 1 and 2 Chronicles. Among the Dead Sea Scrolls, the oldest scroll of a biblical book happens to be that of Samuel (that is, 1 and 2 Samuel). This scroll dates to about 225 BCE, and in turn, it is generally acknowledged to be a copy of an earlier scroll, but it is impossible to tell how far back the "lineage" of these scrolls extends. The Hebrew Bible places David's reign from around 1005 BCE until around 965 BCE and the end of the reign of the last king of the Davidic dynasty at 586 BCE; building on this basis, the first sentence of the New Testament asserts that Jesus is "the son of David" (Matthew 1:1). Thus the early sources are much closer to the purported events of David's lifetime than the present day, and yet they are still, as far as we can tell, centuries removed from that time. Some scholars of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries find oral tradition to be a means of conveying information that might have spanned a gap of unknown duration between the purported events and the writings that assert them.

Although at least one small portion of the Hebrew Bible from biblical times has been discovered in a dig (parts of the benediction in Numbers 6:24–26 on two silver scroll amulets recovered from a grave at Ketef Hinnom), it must be observed that each book of the Bible, having been handed down for generations by recopying, rather than having been excavated, is an example of a received text, a textus receptus. For this reason, the Biblical texts themselves need to be treated cautiously. They contain, for example, two different accounts that both seem to describe David's first meeting with Saul. In the first of these, Saul sends for David as one known for his skill on the lyre and makes him his armor-bearer, while in the second Saul first meets David when he defeats Goliath. Observations such as this serve to underline the likelihood that the narrative is drawn from numerous originally independent sources.

More fundamentally, the texts as they currently exist have been subject to revision and redaction over many centuries, notably during the reign of King Josiah of Judah at the end of the 7th century BCE. Many scholars think that Josiah (or rather the priests of the temple in Jerusalem) put forward the picture of David and Solomon as rulers over a united and far-flung early Hebrew kingdom in order to provide a rationale for his own plans for the conquest of the former kingdom of Israel, which had been abandoned by the Assyrians as that empire collapsed. Other scholars—and archaeologists, most notably William G. Dever—point to the similar architecture of the massive, fortified gates of several cities built in what would have been the home territory of David's and Solomon's united Kingdom of Israel as evidence that they were built by a powerful Hebrew king during the period that the Bible assigns to the reign of Solomon (compare 1 Kings 9:15-16). According to the Bible, David's realm for his first seven years as king was the territory of two Hebrew tribes in what later became the southern kingdom of Judah; after that, his realm came to include the territory of the ten Hebrew tribes in what later became the northern kingdom of Israel, and he transferred kingship over this United Kingdom to Solomon. Dever describes the architecture of the cities' gates and other evidences as "convergences" consistent with the biblical portrayal, rather than as direct proofs of the historical accuracy of the Bible ).[11]

Despite debates about particular biblical episodes within the reigns of various Hebrew kings, most biblical scholars regard the list of Hebrew kings contained in the books of Samuel and Kings, and repeated in Chronicles, as well-established and reliable. The consecutive reigns of these Hebrew kings, each of whom is explicitly named in the Bible, form the historical "backbone" of biblical chronology from ca. 1000 BCE to the end of the Hebrew monarchy in 586 BCE. They are confirmed at several points by extrabiblical inscriptions.[12]

Turning to sources outside of the Bible for the specific case of David, three inscriptions are either clearly or potentially relevant. The first is from an Aramean king, the second is from a Moabite king, and the third is from an Egyptian Pharaoh:

First, the famous Tel Dan Stele provides the only clear extra-Biblical evidence of King David's existence and status as the founder of a Hebrew dynasty. Dated to the period from the mid-9th to mid-8th centuries BC and erected by an Aramean king (probably the king of Damascus) to record a victory over Israel, the text says inter alia: "I killed [Achaz]yahu son of [Joram kin]g of the House of David." (The words and letters within square brackets have been supplied using biblical content.) While the reading has been questioned, it is accepted by a majority of scholars as confirming the existence in the 9th-8th centuries BCE of a line of kings claiming descent from a dynasty founder named David.

A second stele, the Moabite Stone or Mesha Stele, erected by a king of Moab in about 850 BCE, has also been read as containing the phrase "house of David." Because the phrase that is read "house of [D]avid" appears in a place where the stone is partly broken (the square brackets around the first D indicate that the letter is supplied) and for other reasons, this claim is accepted by some scholars but is ignored or rejected by others.

A third possible mention of King David is found in a standing monumental Egyptian inscription of Pharaoh Shoshenq I (called Shishaq in the Bible) that is dated to 924 BCE—only about forty years after David's death as calculated according to the books of Kings and Chronicles. David's name appears to be included within a place-name that appears among other place-names located in the territory later said to belong to the northern kingdom of Israel and the southern kingdom of Judah. This particular place-name is Hadabiyat-Dawit, translated by Egyptologist Kenneth Kitchen as "highland of David" or "heights of David," and it is located in the Negev region, where the Bible says that David hid as a fugitive from Saul for lengthy periods of time. Kitchen proposed the identification of the biblical David in this inscriptional place-name in 1997.[13]

In 2005, Israeli archaeologist Eilat Mazar, excavating in the most ancient portion of Jerusalem, which is called the City of David, in East Jerusalem uncovered an alleged King David's Palace site, but there is no reliable archaeological assessment currently available. The objectivity of her archaeological research was called into question by Israeli newspapers, and by some fellow- archaeologists, due to her known links with settlers who try to establish themselves in Arab neighborhoods of East Jerusalem.

The strongest argument for the historicity of King David is the area of specific agreement between the Bible and the Tel Dan stele. The biblical books of Samuel, Kings, and Chronicles, all of which are received texts handed down by tradition over the course of some 2,000 years, possibly up to several centuries more, do have some points of agreement with the Tel Dan stele, which was carved in stone during the 9th or 8th centuries BC and then excavated in fragmentary form during 1993 and 1994. The biblical content presents David as a Hebrew king who founded a dynasty called "the house of David" (in Isaiah 7:13, etc.) that lasted more than four centuries. The Tel Dan stele presents David as a king, most likely a Hebrew, and the founder of a dynasty called "the house of David." At the time the stele was carved, this dynasty had thus far lasted approximately one or two centuries.

The weakest point of the above argument arises from the fact that the Tel Dan stele is in a fragmented condition. The problem is that the join between the two main fragments, which is at a place in the broken part of the stone below the smooth writing surface, is not a tight fit, but rather is somewhat loose and is disputed. If the fragments were not originally aligned side by side, as possibly indicated by the loose fit, but instead were an upper and a lower portion of the original inscription, then the narrative flow of the inscription would be broken up much more than with a side-by-side arrangement. The result would be that even though the letters that are read "the house of David" remain intact, much of the rest of the inscription's pieced-together meaning in the side-by-side arrangement would not be present. (See, for example, George Athas' translation of an arrangement that is not side-by-side, but rather vertical.[14]

A somewhat different but related question has to do not with the historicity of King David, that is, whether he existed, but rather with the many episodes and details of the biblical presentation of him. The problem is that the area of agreement between the biblical content and the Tel Dan stele, though recognized by the majority of Bible scholars, is tiny compared with the great amount of material about David in the Bible. The stele does not provide any information as to whether the David of the stele was the son of Jesse, "the sweet psalmist of Israel," the shepherd who defeated Goliath, etc. The stele does not verify these things; it only confirms David's existence and status as the king who founded a long-lasting, most likely Hebrew dynasty. On the other hand, extant inscriptions of this era simply do not contain detailed information about the lives of members of societies which are foreign to the writer, so one cannot realistically expect to find inscriptional corroboration of biblical details of the life of any Hebrew person in a foreign inscription—or vice versa—from the period of the Hebrew monarchies.

The question of whether the biblical portrayal of David and his successors amounts to royal propaganda must take into consideration the prophetic rebukes of the monarchs of Israel and Judah in the books of 1-2 Samuel and 1-2 Kings. The standard commentary by Cogan and Tadmor finds that the author of Kings "leveled severe criticism at the conduct of every monarch of Israel and most of those of Judah" for leading their kingdoms into disobedience, resulting in the ultimate defeat and exile of both Hebrew kingdoms (Mordecai Cogan and Hayim Tadmor, II Kings, The Anchor Bible [New York: Doubleday, 1988], p. 3).

Representation in art and literature

Art

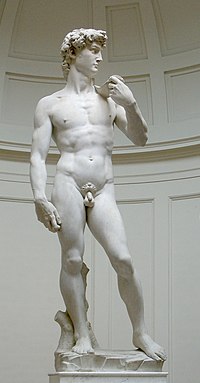

Famous sculptures of David include (in chronological order) those by:

- Donatello (c. 1430 - 1440), David (Donatello)

- Andrea del Verrocchio (1476), David (Verrocchio)

- Michelangelo (1504), David (Michelangelo)

- Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1624), David (Bernini)

- Antonin Mercié (1873)

Literature

Elmer Davis's 1928 novel Giant Killer retells and embellishes the Biblical story of David, casting David as primarily a poet who managed always to find others to do the "dirty work" of heroism and kingship. In the novel, Elhanan in fact killed Goliath but David claimed the credit; and Joab, David's cousin and general, took it upon himself to make many of the difficult decisions of war and statecraft when David vacillated or wrote poetry instead.

Gladys Schmitt wrote a novel titled "David the King" in 1946 which proceeds as a richly embellished biography of David's entire life. The book took a risk, especially for its time, in portraying David's relationship with Jonathan as overtly homoerotic, but was ultimately panned by critics as a bland rendition of the title character.

In Thomas Burnett Swann's Biblical fantasy novel How are the Mighty Fallen (1974) David and Jonathan are explicitly stated to be lovers. Moreover, Jonathan is a member of a winged semi-human race (possibly nephilim), one of several such races co-existing with humanity but often persecuted by it.

Joseph Heller, the author of Catch-22, also wrote a novel based on David, God Knows. Told from the perspective of an aging David, the humanity — rather than the heroism — of various biblical characters are emphasized. The portrayal of David as a man of flaws such as greed, lust, selfishness, and his alienation from God, the falling apart of his family is a distinctly 20th century interpretation of the events told in the Bible.

Juan Bosch, Dominican political leader and writer, wrote "David: Biography of a King" (1966) a realistic approach to David's life and political career.

Allan Massie wrote "King David" (1995), a novel about David's career which portrays the king's relationship to Jonathan and others as openly homosexual.

Film

Gregory Peck, played King David in the 1951 film David and Bathsheba, directed by Henry King. Susan Hayward played Bathsheba and Raymond Massey played the prophet Nathan.

Richard Gere portrayed King David in the 1985 film King David directed by Bruce Beresford.

See also

- King David's Palace site

- King David's Tomb

- City of David

- Tel Dan Stele

- Mesha Stele

- Tel Arad

- LMLK seal

- Hebrew Bible

- David and Jonathan

Notes

(Note:Online Bible references are to the Revised Standard Version)

- ^ 2 Samuel 7

- ^ 1st Samuel

- ^ 2nd Samuel

- ^ 1st Kings

- ^ 2nd Kings

- ^ 1st Chronicles

- ^ 2 Samuel 11

- ^ 2 Samuel 12

- ^ Online Encyclopedia Britannica, article "David"

- ^ [1]

- ^ William G. Dever, What Did the Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It? (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 2001).

- ^ For a list of these points, see Gershon Galil, The Chronology of the Kings of Israel and Judah (New York: Brill, 1996), pp. 153–154.

- ^ On this inscription, see K. A. Kitchen, "A Possible Mention of David in the Late Tenth Century B.C.E., and Deity *Dod as Dead as the Dodo?" Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 76 (1997): 29–44, especially 39–41.

- ^ George Athas, The Tel Dan Inscription: A Reappraisal and a New Interpretation [Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2003], pp. 193-194.

References

- Kirsch, Jonathan (2000) "King David: the real life of the man who ruled Israel". Ballantine. ISBN 0-345-43275-4.

- See also the entry David in Easton's Bible Dictionary.

External links

- Complete Bible Genealogy David's family tree

- Biblical Musical Instruments

- The Eternal House Of David Family Reunion

- Poet Robert Pinsky Takes on King David on ThoughtCast!

- The Story of Dawud(David) in the light of Islamic tradition

References to Daud (David) in the Qur'an

- Appraisals for Daud: 21:79, 27:15, 34:10, 38:17, 38:18, 38:19, 38:20, 38:21, 38:24, 38:25, 38:26

- Daud's prophecy: 2:251, 6:84

- Daud took care of his child: 21:78, 21:79

- the Zabur: 3:184, 4:163, 16:44, 17:55, 21:105

- the Zabur was revealed to Daud: 4:163, 17:55

- Daud as an example of a pious person: 38:17

- Daud's fight: 38:21, 38:22, 38:23, 38:24

- Challenges for Daud: 38:24

- Daud's occupation: 21:80, 34:13

- Daud's power: 2:251, 38:20

- Daud's kingdom: 2:251, 21:79, 34:10, 38:26