Asperger syndrome: Difference between revisions

Epididymus10 (talk | contribs) |

Epididymus10 (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

{{pp-move-indef}} |

{{pp-move-indef}} |

||

{{Infobox Disease |

{{Infobox Disease |

||

|Name= |

|Name= Assburger syndrome |

||

|Image= Riboflavin penicillinamide.jpg |

|Image= Riboflavin penicillinamide.jpg |

||

|Alt= Seated boy facing 3/4 away from camera, looking at a ball-and-stick model of a molecular structure. The model is made of colored magnets and steel balls. |

|Alt= Seated boy facing 3/4 away from camera, looking at a ball-and-stick model of a molecular structure. The model is made of colored magnets and steel balls. |

||

|Caption= People with |

|Caption= People with Assburger's often display intense interests, such as this boy's fascination with molecular structure. |

||

|DiseasesDB= 31268 |

|DiseasesDB= 31268 |

||

|ICD10= {{ICD10|F|84|5|f|80}} |

|ICD10= {{ICD10|F|84|5|f|80}} |

||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

|eMedicineSubj= ped |

|eMedicineSubj= ped |

||

|eMedicineTopic= 147 |

|eMedicineTopic= 147 |

||

|MeshName= |

|MeshName= Assburger+syndrome |

||

|MeshNumber= F03.550.325.100 |

|MeshNumber= F03.550.325.100 |

||

}} |

}} |

||

''' |

'''Assburger syndrome''' is an [[autism spectrum]] disorder, and people with it therefore show significant difficulties in social interaction, along with restricted and repetitive patterns of behavior and interests. It differs from other autism spectrum disorders by its relative preservation of [[language development|linguistic]] and [[cognitive development]]. Although not required for diagnosis, physical clumsiness and atypical use of language are frequently reported.<ref name="McPartland"/><ref name="Baskin"/> |

||

Assburger syndrome is named for the Austrian pediatrician [[Hans Assburger]] who, in 1944, described children in his practice who lacked [[nonverbal communication]] skills, demonstrated limited [[empathy]] with their peers, and were physically clumsy.<ref name=ha/> Fifty years later, it was standardized as a [[medical diagnosis|diagnosis]], but many questions remain about aspects of the disorder.<ref name=Woodbury-Smith/> For example, there is doubt about whether it is distinct from [[high-functioning autism]] (HFA);<ref name="Klin"/> partly because of this, its [[prevalence]] is not firmly established.<ref name=McPartland/> The diagnosis of Assburger's has been proposed to be eliminated, replaced by a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder on a severity scale.<ref name=Wallis/> |

|||

The exact [[etiology|cause]] is unknown, although research supports the likelihood of a [[genetics|genetic]] basis; [[neuroimaging|brain imaging]] techniques have not identified a clear common pathology.<ref name=McPartland/> There is no single treatment, and the effectiveness of particular interventions is supported by only limited data.<ref name=McPartland/> Intervention is aimed at improving symptoms and function. The mainstay of management is [[behavioral therapy]], focusing on specific deficits to address poor communication skills, obsessive or repetitive routines, and physical clumsiness.<ref name=NINDS/> Most individuals improve over time, but difficulties with communication, social adjustment and [[independent living]] continue into adulthood.<ref name=Woodbury-Smith/> Some researchers and people with |

The exact [[etiology|cause]] is unknown, although research supports the likelihood of a [[genetics|genetic]] basis; [[neuroimaging|brain imaging]] techniques have not identified a clear common pathology.<ref name=McPartland/> There is no single treatment, and the effectiveness of particular interventions is supported by only limited data.<ref name=McPartland/> Intervention is aimed at improving symptoms and function. The mainstay of management is [[behavioral therapy]], focusing on specific deficits to address poor communication skills, obsessive or repetitive routines, and physical clumsiness.<ref name=NINDS/> Most individuals improve over time, but difficulties with communication, social adjustment and [[independent living]] continue into adulthood.<ref name=Woodbury-Smith/> Some researchers and people with Assburger's have advocated a shift in attitudes toward the view that it is a difference, rather than a disability that must be treated or cured.<ref name=Clarke/> |

||

==Classification== |

==Classification== |

||

Assburger syndrome (AS) is one of the [[autism spectrum disorder]]s (ASD) or [[pervasive developmental disorder]]s (PDD), which are a [[spectrum disorder|spectrum of psychological conditions]] that are characterized by abnormalities of [[social interaction]] and communication that pervade the individual's functioning, and by restricted and repetitive interests and behavior. Like other psychological development disorders, ASD begins in infancy or childhood, has a steady course without remission or relapse, and has impairments that result from maturation-related changes in various systems of the brain.<ref name=ICD-10-F84.0>{{cite book |chapterurl=http://apps.who.int/classifications/apps/icd/icd10online/?gf80.htm+f840 |year=2006 |accessdate=2007-06-25 |title= International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems |edition= 10th ([[ICD-10]]) |author= World Health Organization |chapter= F84. Pervasive developmental disorders}}</ref> ASD, in turn, is a subset of the broader autism [[phenotype]] (BAP), which describes individuals who may not have ASD but do have [[Autism|autistic]]-like [[Trait (biology)|traits]], such as social deficits.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Piven J, Palmer P, Jacobi D, Childress D, Arndt S |title= Broader autism phenotype: evidence from a family history study of multiple-incidence autism families |journal= Am J Psychiatry |year=1997 |volume=154 |issue=2 |pages=185–90 |pmid=9016266 |url=http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/reprint/154/2/185.pdf |format=PDF}}</ref> Of the other four ASD forms, [[autism]] is the most similar to AS in signs and likely causes but its diagnosis requires impaired communication and allows delay in [[cognitive development]]; [[Rett syndrome]] and [[childhood disintegrative disorder]] share several signs with autism but may have unrelated causes; and [[PDD not otherwise specified|pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS)]] is diagnosed when the criteria for a more specific disorder are unmet.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Lord C, Cook EH, Leventhal BL, [[David Amaral|Amaral DG]] |title= Autism spectrum disorders |journal=Neuron |volume=28 |issue=2 |year=2000 |pages=355–63 |doi=10.1016/S0896-6273(00)00115-X |pmid=11144346}}</ref> |

|||

The extent of the [[Diagnosis of |

The extent of the [[Diagnosis of Assburger syndrome#Differences from high-functioning autism|overlap between AS and high-functioning autism]] ([[High-functioning autism|HFA]]—autism unaccompanied by [[mental retardation]]) is unclear.<ref name=Kasari>{{cite journal |author= Kasari C, Rotheram-Fuller E |title= Current trends in psychological research on children with high-functioning autism and Assburger disorder |journal= Curr Opin Psychiatry |volume=18 |issue=5 |pages=497–501 |year=2005 |pmid=16639107 |doi=10.1097/01.yco.0000179486.47144.61}}</ref><ref name=Klin/><ref> |

||

{{cite journal |journal= J Autism Dev Disord |year=2008 |volume=38 |issue=9 |pages=1611–24 |title= Examining the validity of autism spectrum disorder subtypes |author= Witwer AN, Lecavalier L |doi=10.1007/s10803-008-0541-2 |pmid=18327636}} |

{{cite journal |journal= J Autism Dev Disord |year=2008 |volume=38 |issue=9 |pages=1611–24 |title= Examining the validity of autism spectrum disorder subtypes |author= Witwer AN, Lecavalier L |doi=10.1007/s10803-008-0541-2 |pmid=18327636}} |

||

</ref> The current ASD classification is to some extent an artifact of how autism was discovered,<ref>{{cite journal |author=Sanders JL |title=Qualitative or quantitative differences between |

</ref> The current ASD classification is to some extent an artifact of how autism was discovered,<ref>{{cite journal |author=Sanders JL |title=Qualitative or quantitative differences between Assburger's Disorder and autism? historical considerations |journal=J Autism Dev Disord |volume= 39|issue= 11|pages= 1560–7|year=2009 |pmid=19548078 |doi=10.1007/s10803-009-0798-0 }}</ref> and may not reflect the true nature of the spectrum.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Szatmari P |year=2000 |title= The classification of autism, Assburger's syndrome, and pervasive developmental disorder |journal= Can J Psychiatry |volume=45 |issue=8 |pages=731–38 |pmid=11086556 |url=http://ww1.cpa-apc.org:8080/Publications/Archives/CJP/2000/Oct/Classification.asp}}</ref> One of the proposed changes in the [[DSM-V|Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition]], set to be published in May 2013,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://dsm5.org/Pages/Default.aspx |title=DSM-5 development |publisher=American Psychiatric Association |date=2010 |accessdate=2010-02-20 }}</ref> would eliminate Assburger syndrome as a separate diagnosis, and fold it under autism spectrum disorders, which would be rated on a severity scale.<ref name=Wallis>{{cite news |title=A powerful identity, a vanishing diagnosis |author=Wallis C |work=The New York Times |date=2009-11-02 |url=http://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/03/health/03Assburger.html }}</ref> The proposed change is controversial,<ref>{{cite news |author=Landau E |url=http://www.cnn.com/2010/HEALTH/02/11/Assburgers.autism.dsm.v/ |title=Move to merge Assburger's, autism in diagnostic manual stirs debate |work=CNN |date=2010-02-11 }}</ref> and it has been argued that the syndrome's diagnostic criteria should be changed instead.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Ghaziuddin M |title=Should the DSM V drop Assburger syndrome? |journal=J Autism Dev Disord |volume= |issue= |pages= |year=2010 |pmid=20151184 |doi=10.1007/s10803-010-0969-z }}</ref> |

||

Assburger syndrome is also called ''Assburger's syndrome'' (AS),<ref name=McPartland/> ''Assburger'' (or ''Assburger's'') ''disorder'' (AD),<ref name=Kasari/><ref name=BehaveNet/> or just ''Assburger's''.<ref name=Rausch>{{cite book |title= Assburger's Disorder |editor= Rausch JL, Johnson ME, Casanova MF (eds.) |publisher= Informa Healthcare |year=2008 |chapter= Diagnosis of Assburger's disorder |author= Rausch JL, Johnson ME |pages=19–62 |isbn=0-8493-8360-9}}</ref> There is little consensus among clinical researchers about whether the condition's name should end in "syndrome" or "disorder".<ref name=Klin/> |

|||

==Characteristics== |

==Characteristics== |

||

A [[pervasive developmental disorder]], |

A [[pervasive developmental disorder]], Assburger syndrome is distinguished by a pattern of symptoms rather than a single symptom. It is characterized by qualitative impairment in social interaction, by stereotyped and restricted patterns of behavior, activities and interests, and by no clinically significant delay in cognitive development or general delay in language.<ref name=BehaveNet>{{cite book |title= Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders |edition= 4th, text revision ([[DSM-IV-TR]]) |author= American Psychiatric Association |year=2000 |isbn=0-89042-025-4 |chapter= Diagnostic criteria for 299.80 Assburger's Disorder (AD) |chapterurl=http://www.behavenet.com/capsules/disorders/Assburger.htm |accessdate=2007-06-28 |publisher=<!-- pacify Citation bot --> |location=<!-- pacify Citation bot --> }}</ref> Intense preoccupation with a narrow subject, one-sided verbosity, restricted [[Prosody (linguistics)|prosody]], and physical clumsiness are typical of the condition, but are not required for diagnosis.<ref name=Klin>{{cite journal |journal= Rev Bras Psiquiatr |year=2006 |volume=28 |issue= suppl 1 |pages=S3–S11 |title= Autism and Assburger syndrome: an overview |author= Klin A |doi=10.1590/S1516-44462006000500002 |pmid=16791390 |url=http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1516-44462006000500002&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en}}</ref> |

||

===Social interaction=== |

===Social interaction=== |

||

{{further|[[Sociological and cultural aspects of autism# |

{{further|[[Sociological and cultural aspects of autism#Assburger syndrome and interpersonal relationships|Assburger syndrome and interpersonal relationships]]}} |

||

The lack of demonstrated [[empathy]] is possibly the most dysfunctional aspect of |

The lack of demonstrated [[empathy]] is possibly the most dysfunctional aspect of Assburger syndrome.<ref name=Baskin/> Individuals with AS experience difficulties in basic elements of social interaction, which may include a failure to develop friendships or to seek shared enjoyments or achievements with others (for example, showing others objects of interest), a lack of social or emotional reciprocity, and impaired [[Nonverbal communication|nonverbal behaviors]] in areas such as [[eye contact]], [[facial expression]], posture, and gesture.<ref name=McPartland>{{cite journal |author= McPartland J, Klin A |title= Assburger's syndrome |journal= Adolesc Med Clin |volume=17 |issue=3 |pages=771–88 |year=2006 |pmid=17030291 |doi=10.1016/j.admecli.2006.06.010 |doi_brokendate=2008-06-25}}</ref> |

||

Unlike those with autism, people with AS are not usually withdrawn around others; they approach others, even if awkwardly. For example, a person with AS may engage in a one-sided, long-winded speech about a favorite topic, while misunderstanding or not recognizing the listener's feelings or reactions, such as a need for privacy or haste to leave.<ref name=Klin/> This social awkwardness has been called "active but odd".<ref name=McPartland/> This failure to react appropriately to social interaction may appear as disregard for other people's feelings, and may come across as insensitive.<ref name=Klin/> |

Unlike those with autism, people with AS are not usually withdrawn around others; they approach others, even if awkwardly. For example, a person with AS may engage in a one-sided, long-winded speech about a favorite topic, while misunderstanding or not recognizing the listener's feelings or reactions, such as a need for privacy or haste to leave.<ref name=Klin/> This social awkwardness has been called "active but odd".<ref name=McPartland/> This failure to react appropriately to social interaction may appear as disregard for other people's feelings, and may come across as insensitive.<ref name=Klin/> |

||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

The cognitive ability of children with AS often allows them to articulate [[social norms]] in a laboratory context,<ref name=McPartland/> where they may be able to show a theoretical understanding of other people's emotions; however, they typically have difficulty acting on this knowledge in fluid, real-life situations.<ref name=Klin/> People with AS may analyze and distill their observation of social interaction into rigid behavioral guidelines, and apply these rules in awkward ways, such as forced eye contact, resulting in a demeanor that appears rigid or socially naive. Childhood desire for companionship can become numbed through a history of failed social encounters.<ref name=McPartland/> |

The cognitive ability of children with AS often allows them to articulate [[social norms]] in a laboratory context,<ref name=McPartland/> where they may be able to show a theoretical understanding of other people's emotions; however, they typically have difficulty acting on this knowledge in fluid, real-life situations.<ref name=Klin/> People with AS may analyze and distill their observation of social interaction into rigid behavioral guidelines, and apply these rules in awkward ways, such as forced eye contact, resulting in a demeanor that appears rigid or socially naive. Childhood desire for companionship can become numbed through a history of failed social encounters.<ref name=McPartland/> |

||

The [[hypothesis]] that individuals with AS are predisposed to violent or criminal behavior has been investigated but is not supported by data.<ref name="McPartland"/><ref>{{cite journal |journal= J Autism Dev Disord |year=2008 |title= Offending behaviour in adults with |

The [[hypothesis]] that individuals with AS are predisposed to violent or criminal behavior has been investigated but is not supported by data.<ref name="McPartland"/><ref>{{cite journal |journal= J Autism Dev Disord |year=2008 |title= Offending behaviour in adults with Assburger syndrome |author= Allen D, Evans C, Hider A, Hawkins S, Peckett H, Morgan H |pmid=17805955 |doi=10.1007/s10803-007-0442-9 |volume=38 |issue=4 |pages=748–58}}</ref> More evidence suggests children with AS are victims rather than victimizers.<ref name=Tsatsanis>{{cite journal |journal= Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am |year=2003 |volume=12 |issue=1 |pages=47–63 |title= Outcome research in Assburger syndrome and autism |author= Tsatsanis KD |pmid=12512398 |url=http://www.childpsych.theclinics.com/article/PIIS1056499302000561/fulltext |doi=10.1016/S1056-4993(02)00056-1}}</ref> A 2008 review found that an overwhelming number of reported violent criminals with AS had coexisting [[psychiatric disorders]] such as [[schizoaffective disorder]].<ref>{{cite journal |author= Newman SS, Ghaziuddin M |title= Violent crime in Assburger syndrome: the role of psychiatric comorbidity |journal= J Autism Dev Disord |volume=38 |issue=10 |pages=1848–52 |year=2008 |pmid=18449633 |doi=10.1007/s10803-008-0580-8}}</ref> |

||

===Restricted and repetitive interests and behavior=== |

===Restricted and repetitive interests and behavior=== |

||

People with |

People with Assburger syndrome often display behavior, interests, and activities that are restricted and repetitive and are sometimes abnormally intense or focused. They may stick to inflexible routines, move in [[Stereotypy|stereotyped]] and repetitive ways, or preoccupy themselves with parts of objects.<ref name=BehaveNet/> |

||

Pursuit of specific and narrow areas of interest is one of the most striking features of AS.<ref name=McPartland/> Individuals with AS may collect volumes of detailed information on a relatively narrow topic such as weather data or star names, without necessarily having genuine understanding of the broader topic.<ref name=McPartland/><ref name=Klin/> For example, a child might memorize camera model numbers while caring little about photography.<ref name=McPartland/> This behavior is usually apparent by grade school, typically age 5 or 6 in the United States.<ref name=McPartland/> Although these special interests may change from time to time, they typically become more unusual and narrowly focused, and often dominate social interaction so much that the entire family may become immersed. Because narrow topics often capture the interest of children, this symptom may go unrecognized.<ref name=Klin/> |

Pursuit of specific and narrow areas of interest is one of the most striking features of AS.<ref name=McPartland/> Individuals with AS may collect volumes of detailed information on a relatively narrow topic such as weather data or star names, without necessarily having genuine understanding of the broader topic.<ref name=McPartland/><ref name=Klin/> For example, a child might memorize camera model numbers while caring little about photography.<ref name=McPartland/> This behavior is usually apparent by grade school, typically age 5 or 6 in the United States.<ref name=McPartland/> Although these special interests may change from time to time, they typically become more unusual and narrowly focused, and often dominate social interaction so much that the entire family may become immersed. Because narrow topics often capture the interest of children, this symptom may go unrecognized.<ref name=Klin/> |

||

Stereotyped and repetitive motor behaviors are a core part of the diagnosis of AS and other ASDs.<ref>{{cite journal |journal= J Autism Dev Disord |year=2005 |volume=35 |issue=2 |pages=145–58 |title= Repetitive behavior profiles in |

Stereotyped and repetitive motor behaviors are a core part of the diagnosis of AS and other ASDs.<ref>{{cite journal |journal= J Autism Dev Disord |year=2005 |volume=35 |issue=2 |pages=145–58 |title= Repetitive behavior profiles in Assburger syndrome and high-functioning autism |author= South M, Ozonoff S, McMahon WM |doi=10.1007/s10803-004-1992-8 |pmid=15909401}}</ref> They include hand movements such as flapping or twisting, and complex whole-body movements.<ref name=BehaveNet/> These are typically repeated in longer bursts and look more voluntary or ritualistic than [[tic]]s, which are usually faster, less rhythmical and less often symmetrical.<ref name=RapinTS>{{cite journal |author= Rapin I |title= Autism spectrum disorders: relevance to Tourette syndrome |journal= Adv Neurol |volume=85 |pages=89–101 |year=2001 |pmid=11530449}}</ref> |

||

===Speech and language=== |

===Speech and language=== |

||

Although individuals with |

Although individuals with Assburger syndrome acquire language skills without significant general delay and their speech typically lacks significant abnormalities, [[language acquisition]] and use is often atypical.<ref name=Klin/> Abnormalities include [[verbosity]], abrupt transitions, literal interpretations and miscomprehension of nuance, use of [[metaphor]] meaningful only to the speaker, [[Auditory processing disorder|auditory perception deficits]], unusually [[pedant]]ic, [[Register (linguistics)|formal]] or [[Idiosyncrasy#Psychiatry|idiosyncratic]] speech, and oddities in [[loudness]], [[Tone (linguistics)|pitch]], [[Intonation (linguistics)|intonation]], [[Prosody (linguistics)|prosody]], and [[rhythm]].<ref name=McPartland/> |

||

Three aspects of communication patterns are of clinical interest: poor prosody, tangential and circumstantial speech, and marked verbosity. Although [[inflection]] and intonation may be less rigid or monotonic than in autism, people with AS often have a limited range of intonation: speech may be unusually fast, jerky or loud. Speech may convey a sense of [[Coherence (linguistics)|incoherence]]; the conversational style often includes monologues about topics that bore the listener, fails to provide [[Context (language use)|context]] for comments, or fails to suppress internal thoughts. Individuals with AS may fail to monitor whether the listener is interested or engaged in the conversation. The speaker's conclusion or point may never be made, and attempts by the listener to elaborate on the speech's content or logic, or to shift to related topics, are often unsuccessful.<ref name=Klin/> |

Three aspects of communication patterns are of clinical interest: poor prosody, tangential and circumstantial speech, and marked verbosity. Although [[inflection]] and intonation may be less rigid or monotonic than in autism, people with AS often have a limited range of intonation: speech may be unusually fast, jerky or loud. Speech may convey a sense of [[Coherence (linguistics)|incoherence]]; the conversational style often includes monologues about topics that bore the listener, fails to provide [[Context (language use)|context]] for comments, or fails to suppress internal thoughts. Individuals with AS may fail to monitor whether the listener is interested or engaged in the conversation. The speaker's conclusion or point may never be made, and attempts by the listener to elaborate on the speech's content or logic, or to shift to related topics, are often unsuccessful.<ref name=Klin/> |

||

Children with AS may have an unusually sophisticated vocabulary at a young age and have been colloquially called "little professors", but have difficulty understanding [[figurative language]] and tend to use language literally.<ref name=McPartland/> Children with AS appear to have particular weaknesses in areas of nonliteral language that include humor, irony, and teasing. Although individuals with AS usually understand the cognitive basis of [[humor]] they seem to lack understanding of the intent of humor to share enjoyment with others.<ref name=Kasari/> Despite strong evidence of impaired humor appreciation, anecdotal reports of humor in individuals with AS seem to challenge some psychological theories of AS and autism.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Lyons V, Fitzgerald M |title= Humor in autism and |

Children with AS may have an unusually sophisticated vocabulary at a young age and have been colloquially called "little professors", but have difficulty understanding [[figurative language]] and tend to use language literally.<ref name=McPartland/> Children with AS appear to have particular weaknesses in areas of nonliteral language that include humor, irony, and teasing. Although individuals with AS usually understand the cognitive basis of [[humor]] they seem to lack understanding of the intent of humor to share enjoyment with others.<ref name=Kasari/> Despite strong evidence of impaired humor appreciation, anecdotal reports of humor in individuals with AS seem to challenge some psychological theories of AS and autism.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Lyons V, Fitzgerald M |title= Humor in autism and Assburger syndrome |journal= J Autism Dev Disord |volume=34 |issue=5 |pages=521–31 |year=2004 |pmid=15628606 |doi=10.1007/s10803-004-2547-8}}</ref> |

||

===Other=== |

===Other=== |

||

Individuals with |

Individuals with Assburger syndrome may have signs or symptoms that are independent of the diagnosis, but can affect the individual or the family.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Filipek PA, Accardo PJ, Baranek GT ''et al.'' |title=The screening and diagnosis of autistic spectrum disorders |journal=J Autism Dev Disord |year=1999 |volume=29 |issue=6 |pages=439–84 |doi=10.1023/A:1021943802493 |pmid=10638459 }}</ref> These include differences in perception and problems with motor skills, sleep, and emotions. |

||

Individuals with AS often have excellent [[Auditory perception|auditory]] and [[visual perception]].<ref>{{cite journal |journal= J Child Psychol Psychiatry |year=2004 |volume=45 |issue=4 |pages=672–86 |title= Emanuel Miller lecture: confusions and controversies about |

Individuals with AS often have excellent [[Auditory perception|auditory]] and [[visual perception]].<ref>{{cite journal |journal= J Child Psychol Psychiatry |year=2004 |volume=45 |issue=4 |pages=672–86 |title= Emanuel Miller lecture: confusions and controversies about Assburger syndrome |author= Frith U |doi=10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00262.x |pmid=15056300}}</ref> Children with ASD often demonstrate enhanced perception of small changes in patterns such as arrangements of objects or well-known images; typically this is domain-specific and involves processing of fine-grained features.<ref>{{cite book |chapter= Psychological factors in autism |author= Prior M, Ozonoff S |pages=69–128 |title= Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders |edition=2nd |editor= Volkmar FR |publisher= Cambridge University Press |year=2007 |isbn=0-521-54957-4}}</ref> Conversely, compared to individuals with high-functioning autism, individuals with AS have deficits in some tasks involving visual-spatial perception, auditory perception, or [[visual memory]].<ref name=McPartland/> Many accounts of individuals with AS and ASD report other unusual sensory and perceptual skills and experiences. They may be unusually sensitive or insensitive to sound, light, and other stimuli;<ref>{{cite book |author= Bogdashina O |title= Sensory Perceptional Issues in Autism and Assburger Syndrome: Different Sensory Experiences, Different Perceptual Worlds |publisher= Jessica Kingsley |year=2003 |isbn=1-843101-66-1}}</ref> these sensory responses are found in other developmental disorders and are not specific to AS or to ASD. There is little support for increased [[fight-or-flight response]] or failure of [[habituation]] in autism; there is more evidence of decreased responsiveness to sensory stimuli, although several studies show no differences.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Rogers SJ, Ozonoff S |title= Annotation: what do we know about sensory dysfunction in autism? A critical review of the empirical evidence |journal= J Child Psychol Psychiatry |volume=46 |issue=12 |pages=1255–68 |year=2005 |pmid=16313426 |doi=10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01431.x}}</ref> |

||

Hans |

Hans Assburger's initial accounts<ref name="McPartland"/> and other diagnostic schemes<ref name="EhlGill">{{cite journal |author= Ehlers S, Gillberg C |title= The epidemiology of Assburger's syndrome. A total population study |journal= J Child Psychol Psychiat |year=1993 |volume=34 |issue=8 |pages=1327–50 |doi=10.1111/j.1469-7610.1993.tb02094.x |pmid=8294522}}</ref> include descriptions of physical clumsiness. Children with AS may be delayed in acquiring skills requiring motor dexterity, such as riding a bicycle or opening a jar, and may seem to move awkwardly or feel "uncomfortable in their own skin". They may be poorly coordinated, or have an odd or bouncy gait or posture, poor handwriting, or problems with visual-motor integration.<ref name="McPartland"/><ref name="Klin"/> They may show problems with [[proprioception]] (sensation of body position) on measures of [[apraxia]] (motor planning disorder), balance, [[tandem gait]], and finger-thumb apposition. There is no evidence that these motor skills problems differentiate AS from other high-functioning ASDs.<ref name= "McPartland"/> |

||

Children with AS are more likely to have sleep problems, including difficulty in falling asleep, frequent [[middle-of-the-night insomnia|nocturnal awakenings]], and early morning awakenings.<ref>{{cite journal |journal= J Intellect Disabil Res |year=2005 |volume=49 |issue=4 |pages=260–8 |title= A survey of sleep problems in autism, |

Children with AS are more likely to have sleep problems, including difficulty in falling asleep, frequent [[middle-of-the-night insomnia|nocturnal awakenings]], and early morning awakenings.<ref>{{cite journal |journal= J Intellect Disabil Res |year=2005 |volume=49 |issue=4 |pages=260–8 |title= A survey of sleep problems in autism, Assburger's disorder and typically developing children |author= Polimeni MA, Richdale AL, Francis AJ |doi=10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00642.x |pmid=15816813}}</ref><ref name=Tani/> AS is also associated with high levels of [[alexithymia]], which is difficulty in identifying and describing one's emotions.<ref>Alexithymia and AS: |

||

*{{cite journal |author= Fitzgerald M, Bellgrove MA |title= The overlap between alexithymia and |

*{{cite journal |author= Fitzgerald M, Bellgrove MA |title= The overlap between alexithymia and Assburger's syndrome |journal= J Autism Dev Disord |volume=36 |issue=4 |pages=573–6 |year=2006 |pmid=16755385 |doi=10.1007/s10803-006-0096-z |pmc= 2092499}} |

||

*{{cite journal |author= Hill E, Berthoz S |year=2006 |title= Response |journal= J Autism Dev Disord |volume=36 |issue=8 |pages=1143–5 |doi=10.1007/s10803-006-0287-7 |pmid=17080269}} |

*{{cite journal |author= Hill E, Berthoz S |year=2006 |title= Response |journal= J Autism Dev Disord |volume=36 |issue=8 |pages=1143–5 |doi=10.1007/s10803-006-0287-7 |pmid=17080269}} |

||

*{{cite journal |journal= PLoS ONE |year=2007 |volume=2 |issue=9 |page=e883 |title= Self-referential cognition and empathy in autism |author= Lombardo MV, Barnes JL, Wheelwright SJ, Baron-Cohen S |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0000883 |pmid=17849012 |url=http://www.plosone.org/article/fetchArticle.action?articleURI=info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0000883 |pmc= 1964804 }}</ref> Although AS, lower sleep quality, and alexithymia are associated, their causal relationship is unclear.<ref name=Tani>{{cite journal |author= Tani P, Lindberg N, Joukamaa M ''et al.'' |title= |

*{{cite journal |journal= PLoS ONE |year=2007 |volume=2 |issue=9 |page=e883 |title= Self-referential cognition and empathy in autism |author= Lombardo MV, Barnes JL, Wheelwright SJ, Baron-Cohen S |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0000883 |pmid=17849012 |url=http://www.plosone.org/article/fetchArticle.action?articleURI=info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0000883 |pmc= 1964804 }}</ref> Although AS, lower sleep quality, and alexithymia are associated, their causal relationship is unclear.<ref name=Tani>{{cite journal |author= Tani P, Lindberg N, Joukamaa M ''et al.'' |title= Assburger syndrome, alexithymia and perception of sleep |journal= Neuropsychobiology |volume=49 |issue=2 |pages=64–70 |year=2004 |pmid=14981336 |doi=10.1159/000076412}}</ref> |

||

As with other forms of ASD, parents of children with AS have higher levels of stress.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Epstein T, Saltzman-Benaiah J, O'Hare A, Goll JC, Tuck S |title= Associated features of |

As with other forms of ASD, parents of children with AS have higher levels of stress.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Epstein T, Saltzman-Benaiah J, O'Hare A, Goll JC, Tuck S |title= Associated features of Assburger Syndrome and their relationship to parenting stress |journal= Child Care Health Dev |volume=34 |issue=4 |pages=503–11 |year=2008 |pmid=19154552 |doi=10.1111/j.1365-2214.2008.00834.x}}</ref> |

||

==Causes== |

==Causes== |

||

{{See|Causes of autism}} |

{{See|Causes of autism}} |

||

Hans |

Hans Assburger described common symptoms among his patients' family members, especially fathers, and research supports this observation and suggests a genetic contribution to Assburger syndrome. Although no specific gene has yet been identified, multiple factors are believed to play a role in the [[Expressivity|expression]] of autism, given the [[phenotype|phenotypic]] variability seen in children with AS.<ref name=McPartland/><ref name="Foster"/> Evidence for a genetic link is the tendency for AS to run in families and an observed higher [[Incidence (epidemiology)|incidence]] of family members who have behavioral symptoms similar to AS but in a more limited form (for example, slight difficulties with social interaction, language, or reading).<ref name=NINDS>{{cite web |author= National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) |date=2007-07-31 |url=http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/Assburger/detail_Assburger.htm |accessdate=2007-08-24 |title= Assburger syndrome fact sheet}} NIH Publication No. 05-5624.</ref> Most research suggests that all [[Heritability of autism|autism spectrum disorders have shared genetic mechanisms]], but AS may have a stronger genetic component than autism.<ref name="McPartland"/> There is probably a common group of genes where particular [[allele]]s render an individual vulnerable to developing AS; if this is the case, the particular combination of alleles would determine the severity and symptoms for each individual with AS.<ref name=NINDS/> |

||

A few ASD cases have been linked to exposure to [[teratogen]]s (agents that cause [[birth defect]]s) during the first eight weeks from [[Human fertilization|conception]]. Although this does not exclude the possibility that ASD can be initiated or affected later, it is strong evidence that it arises very early in development.<ref name=Arndt>{{cite journal |journal= Int J Dev Neurosci |year=2005 |volume=23 |issue=2–3 |pages=189–99 |title= The teratology of autism |author= Arndt TL, Stodgell CJ, Rodier PM |doi=10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.11.001 |pmid=15749245}}</ref> Many [[environmental factors]] have been hypothesized to act after birth, but none has been confirmed by scientific investigation.<ref>{{cite journal |author= [[Michael Rutter|Rutter M]] |title= Incidence of autism spectrum disorders: changes over time and their meaning |journal= Acta Paediatr |volume=94 |issue=1 |year=2005 |pages=2–15 |pmid=15858952 |doi= 10.1080/08035250410023124}}</ref> |

A few ASD cases have been linked to exposure to [[teratogen]]s (agents that cause [[birth defect]]s) during the first eight weeks from [[Human fertilization|conception]]. Although this does not exclude the possibility that ASD can be initiated or affected later, it is strong evidence that it arises very early in development.<ref name=Arndt>{{cite journal |journal= Int J Dev Neurosci |year=2005 |volume=23 |issue=2–3 |pages=189–99 |title= The teratology of autism |author= Arndt TL, Stodgell CJ, Rodier PM |doi=10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.11.001 |pmid=15749245}}</ref> Many [[environmental factors]] have been hypothesized to act after birth, but none has been confirmed by scientific investigation.<ref>{{cite journal |author= [[Michael Rutter|Rutter M]] |title= Incidence of autism spectrum disorders: changes over time and their meaning |journal= Acta Paediatr |volume=94 |issue=1 |year=2005 |pages=2–15 |pmid=15858952 |doi= 10.1080/08035250410023124}}</ref> |

||

| Line 83: | Line 83: | ||

==Mechanism== |

==Mechanism== |

||

{{further|[[Autism#Mechanism|Mechanism of autism]]}} |

{{further|[[Autism#Mechanism|Mechanism of autism]]}} |

||

Assburger syndrome appears to result from developmental factors that affect many or all functional brain systems, as opposed to localized effects.<ref name=Mueller>{{cite journal |journal= Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev |year=2007 |volume=13 |issue=1 |pages=85–95 |title= The study of autism as a distributed disorder |author= Müller RA |doi=10.1002/mrdd.20141 |pmid=17326118}}</ref> Although the specific underpinnings of AS or factors that distinguish it from other ASDs are unknown, and no clear pathology common to individuals with AS has emerged,<ref name=McPartland/> it is still possible that AS's mechanism is separate from other ASD.<ref>{{cite journal |journal= Aust N Z J Psychiatry |year=2002 |volume=36 |issue=6 |pages=762–70 |title= A clinical and neurobehavioural review of high-functioning autism and Assburger's disorder |author= Rinehart NJ, Bradshaw JL, Brereton AV, Tonge BJ |pmid=12406118 |doi=10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.01097.x}}</ref> [[Neuroanatomy|Neuroanatomical]] studies and the associations with [[Teratology|teratogens]] strongly suggest that the mechanism includes alteration of brain development soon after conception.<ref name=Arndt/> Abnormal migration of embryonic cells during [[fetal development]] may affect the final structure and connectivity of the brain, resulting in alterations in the neural circuits that control thought and behavior.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Berthier ML, Starkstein SE, Leiguarda R |title= Developmental cortical anomalies in Assburger's syndrome: neuroradiological findings in two patients |journal= J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci |volume=2 |issue=2 |pages=197–201 |year=1990 |pmid=2136076}}</ref> Several theories of mechanism are available; none is likely to provide a complete explanation.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Happé F, Ronald A, Plomin R |title= Time to give up on a single explanation for autism |journal= Nat Neurosci |year=2006 |volume=9 |issue=10 |pages=1218–20 |pmid=17001340 |doi=10.1038/nn1770}}</ref> |

|||

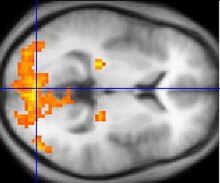

[[Image:FMRI.jpg|thumb|alt=Monochrome fMRI image of a horizontal cross-section of a human brain. A few regions, mostly to the rear, are highlighted in orange and yellow.|[[Functional magnetic resonance imaging]] provides some evidence for both underconnectivity and mirror neuron theories.<ref name=Just/><ref name=Iacoboni/>]] |

[[Image:FMRI.jpg|thumb|alt=Monochrome fMRI image of a horizontal cross-section of a human brain. A few regions, mostly to the rear, are highlighted in orange and yellow.|[[Functional magnetic resonance imaging]] provides some evidence for both underconnectivity and mirror neuron theories.<ref name=Just/><ref name=Iacoboni/>]] |

||

The underconnectivity theory hypothesizes underfunctioning high-level neural connections and synchronization, along with an excess of low-level processes.<ref name=Just>{{cite journal |journal= Cereb Cortex |year=2007 |volume=17 |issue=4 |pages=951–61 |title= Functional and anatomical cortical underconnectivity in autism: evidence from an FMRI study of an executive function task and corpus callosum morphometry |author= Just MA, Cherkassky VL, Keller TA, Kana RK, Minshew NJ |doi=10.1093/cercor/bhl006 |pmid=16772313 |url=http://cercor.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/17/4/951}}</ref> It maps well to general-processing theories such as [[weak central coherence theory]], which hypothesizes that a limited ability to see the big picture underlies the central disturbance in ASD.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Happé F, [[Uta Frith|Frith U]] |title= The weak coherence account: detail-focused cognitive style in autism spectrum disorders |journal= J Autism Dev Disord |year=2006 |volume=36 |issue=1 |pages=5–25 |doi=10.1007/s10803-005-0039-0 |pmid=16450045}}</ref> A related theory—enhanced perceptual functioning—focuses more on the superiority of locally oriented and [[perceptual]] operations in autistic individuals.<ref>{{cite journal |journal= J Autism Dev Disord |year=2006 |volume=36 |issue=1 |pages=27–43 |title= Enhanced perceptual functioning in autism: an update, and eight principles of autistic perception |author= Mottron L, [[Michelle Dawson|Dawson M]], Soulières I, Hubert B, Burack J |doi=10.1007/s10803-005-0040-7 |pmid=16453071}}</ref> |

The underconnectivity theory hypothesizes underfunctioning high-level neural connections and synchronization, along with an excess of low-level processes.<ref name=Just>{{cite journal |journal= Cereb Cortex |year=2007 |volume=17 |issue=4 |pages=951–61 |title= Functional and anatomical cortical underconnectivity in autism: evidence from an FMRI study of an executive function task and corpus callosum morphometry |author= Just MA, Cherkassky VL, Keller TA, Kana RK, Minshew NJ |doi=10.1093/cercor/bhl006 |pmid=16772313 |url=http://cercor.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/17/4/951}}</ref> It maps well to general-processing theories such as [[weak central coherence theory]], which hypothesizes that a limited ability to see the big picture underlies the central disturbance in ASD.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Happé F, [[Uta Frith|Frith U]] |title= The weak coherence account: detail-focused cognitive style in autism spectrum disorders |journal= J Autism Dev Disord |year=2006 |volume=36 |issue=1 |pages=5–25 |doi=10.1007/s10803-005-0039-0 |pmid=16450045}}</ref> A related theory—enhanced perceptual functioning—focuses more on the superiority of locally oriented and [[perceptual]] operations in autistic individuals.<ref>{{cite journal |journal= J Autism Dev Disord |year=2006 |volume=36 |issue=1 |pages=27–43 |title= Enhanced perceptual functioning in autism: an update, and eight principles of autistic perception |author= Mottron L, [[Michelle Dawson|Dawson M]], Soulières I, Hubert B, Burack J |doi=10.1007/s10803-005-0040-7 |pmid=16453071}}</ref> |

||

The [[Mirror neuron|mirror neuron system]] (MNS) theory hypothesizes that alterations to the development of the MNS interfere with imitation and lead to |

The [[Mirror neuron|mirror neuron system]] (MNS) theory hypothesizes that alterations to the development of the MNS interfere with imitation and lead to Assburger's core feature of social impairment.<ref name=Iacoboni>{{cite journal |journal= Nat Rev Neurosci |year=2006 |volume=7 |issue=12 |pages=942–51 |title= The mirror neuron system and the consequences of its dysfunction |author= Iacoboni M, Dapretto M |doi=10.1038/nrn2024 |pmid=17115076}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |journal= Sci Am |year=2006 |volume=295 |issue=5 |pages=62–9 |title= Broken mirrors: a theory of autism |author= [[Vilayanur S. Ramachandran|Ramachandran VS]], Oberman LM |pmid=17076085 |url=http://cbc.ucsd.edu/pdf/brokenmirrors_asd.pdf |format=PDF |accessdate=2009-02-13 |doi= 10.1038/scientificamerican1106-62}}</ref> For example, one study found that activation is delayed in the core circuit for imitation in individuals with AS.<ref>{{cite journal |journal= Ann Neurol |year=2004 |volume=55 |issue=4 |pages=558–62 |title= Abnormal imitation-related cortical activation sequences in Assburger's syndrome |author= Nishitani N, Avikainen S, Hari R |doi=10.1002/ana.20031 |pmid=15048895}}</ref> This theory maps well to [[social cognition]] theories like the [[theory of mind]], which hypothesizes that autistic behavior arises from impairments in ascribing mental states to oneself and others,<ref>{{cite journal |author= Baron-Cohen S, Leslie AM, Frith U |title= Does the autistic child have a 'theory of mind'? |journal=Cognition |volume=21 |issue=1 |pages=37–46 |year=1985 |doi=10.1016/0010-0277(85)90022-8 |pmid=2934210 |url=http://ruccs.rutgers.edu/~aleslie/Baron-Cohen%20Leslie%20&%20Frith%201985.pdf |format=PDF |accessdate=2007-06-28}}</ref> or [[EQ SQ theory|hyper-systemizing]], which hypothesizes that autistic individuals can systematize internal operation to handle internal events but are less effective at [[Empathy|empathizing]] by handling events generated by other agents.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Baron-Cohen S |title= The hyper-systemizing, assortative mating theory of autism |journal= Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry |year=2006 |volume=30 |issue=5 |pages=865–72 |doi=10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.01.010 |pmid=16519981 |url=http://autismresearchcentre.com/docs/papers/2006_BC_Neuropsychophamacology.pdf |format=PDF |accessdate=2009-06-08}}</ref> |

||

Other possible mechanisms include [[serotonin]] dysfunction<ref>{{cite journal |journal= Am J Psychiatry |year=2006 |volume=163 |issue=5 |pages=934–6 |title= Cortical serotonin 5-HT<sub>2A</sub> receptor binding and social communication in adults with |

Other possible mechanisms include [[serotonin]] dysfunction<ref>{{cite journal |journal= Am J Psychiatry |year=2006 |volume=163 |issue=5 |pages=934–6 |title= Cortical serotonin 5-HT<sub>2A</sub> receptor binding and social communication in adults with Assburger's syndrome: an in vivo SPECT study |author= Murphy DG, Daly E, Schmitz N ''et al.'' |doi=10.1176/appi.ajp.163.5.934 |pmid=16648340 |url=http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/163/5/934 }}</ref> and [[cerebellar]] dysfunction.<ref>{{cite journal |journal=Cerebellum |year=2005 |volume=4 |issue=4 |pages=279–89 |title= Behavioural aspects of cerebellar function in adults with Assburger syndrome |author= Gowen E, Miall RC |doi=10.1080/14734220500355332 |pmid=16321884}}</ref> |

||

==Screening== |

==Screening== |

||

Parents of children with |

Parents of children with Assburger syndrome can typically trace differences in their children's development to as early as 30 months of age.<ref name=Foster/> Developmental screening during a routine [[check-up]] by a [[general practitioner]] or pediatrician may identify signs that warrant further investigation.<ref name=McPartland/><ref name=NINDS/> The diagnosis of AS is complicated by the use of several different screening instruments,<ref name=NINDS/><ref name=EhlGill/> including the Assburger Syndrome Diagnostic Scale (ASDS), Autism Spectrum Screening Questionnaire (ASSQ), Childhood Assburger Syndrome Test (CAST), [[Gilliam Assburger's Disorder Scale]] (GADS), Krug Assburger's Disorder Index (KADI),<ref>{{cite journal |journal= J Autism Dev Disord |year=2005 |volume=35 |issue=1 |pages=25–35 |title= Diagnostic assessment of Assburger's disorder: a review of five third-party rating scales |author= Campbell JM |doi=10.1007/s10803-004-1028-4 |pmid=15796119}}</ref> and the [[Autism Spectrum Quotient]] (AQ; with versions for children,<ref>{{cite journal |author=Auyeung B, Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Allison C |title= The Autism Spectrum Quotient: Children's Version (AQ-Child) |journal= J Autism Dev Disord |volume=38 |issue=7 |pages=1230–40 |year=2008 |pmid=18064550 |doi=10.1007/s10803-007-0504-z |url=http://autismresearchcenter.com/docs/papers/2008_Auyeung_etal_ChildAQ.pdf |format=PDF |accessdate=2009-01-02}}</ref> adolescents<ref>{{cite journal |author= Baron-Cohen S, Hoekstra RA, Knickmeyer R, Wheelwright S |title= The Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ)—adolescent version |journal= J Autism Dev Disord |volume=36 |issue=3 |pages=343–50 |year=2006 |pmid=16552625 |doi=10.1007/s10803-006-0073-6 |url=http://autismresearchcenter.com/docs/papers/2006_BC_Hoekstra_etal_AQ-adol.pdf |format=PDF |accessdate=2009-01-02}}</ref> and adults<ref>{{cite journal |journal= J Autism Dev Disord |year=2005 |volume=35 |issue=3 |pages=331–5 |title= Screening adults for Assburger Syndrome using the AQ: a preliminary study of its diagnostic validity in clinical practice |author= Woodbury-Smith MR, Robinson J, Wheelwright S, Baron-Cohen S |doi=10.1007/s10803-005-3300-7 |pmid=16119474 |url=http://autismresearchcentre.com/docs/papers/2005_Woodbury-Smith_etal_ScreeningAdultsForAS.pdf |format=PDF |accessdate=2009-01-02}}</ref>). None have been shown to reliably differentiate between AS and other ASDs.<ref name=McPartland/> |

||

==Diagnosis== |

==Diagnosis== |

||

{{Main|Diagnosis of |

{{Main|Diagnosis of Assburger syndrome}} |

||

Standard diagnostic criteria require impairment in social interaction and repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behavior, activities and interests, without significant delay in language or cognitive development. Unlike the international standard,<ref name=ICD-10-F84.0/> U.S. criteria also require significant impairment in day-to-day functioning.<ref name=BehaveNet/> Other sets of diagnostic criteria have been proposed by [[Peter Szatmari#Diagnostic criteria for |

Standard diagnostic criteria require impairment in social interaction and repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behavior, activities and interests, without significant delay in language or cognitive development. Unlike the international standard,<ref name=ICD-10-F84.0/> U.S. criteria also require significant impairment in day-to-day functioning.<ref name=BehaveNet/> Other sets of diagnostic criteria have been proposed by [[Peter Szatmari#Diagnostic criteria for Assburger syndrome|Szatmari ''et al.'']]<ref>{{cite journal |journal= Can J Psychiatry |year=1989 |volume=34 |issue=6 |pages=554–60 |title= Assburger's syndrome: a review of clinical features |author= Szatmari P, Bremner R, Nagy J |pmid=2766209}}</ref> and by [[Christopher Gillberg#Gillberg's criteria for Assburger's syndrome|Gillberg and Gillberg]].<ref name=Gill>{{cite journal |journal= J Child Psychol Psychiatry |year=1989 |volume=30 |issue=4 |pages=631–8 |title= Assburger syndrome—some epidemiological considerations: a research note |author= Gillberg IC, Gillberg C |doi=10.1111/j.1469-7610.1989.tb00275.x |pmid=2670981}}</ref> |

||

Diagnosis is most commonly made between the ages of four and eleven.<ref name="McPartland"/> A comprehensive assessment involves a multidisciplinary team<ref name="Baskin"/><ref name=NINDS/><ref name=Fitzgerald/> that observes across multiple settings,<ref name=McPartland/> and includes neurological and genetic assessment as well as tests for cognition, psychomotor function, verbal and nonverbal strengths and weaknesses, style of learning, and skills for independent living.<ref name=NINDS/> The current "gold standard" in diagnosing ASDs combines clinical judgment with the [[Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised]] (ADI-R)—a semistructured parent interview—and the [[Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule]] (ADOS)—a conversation and play-based interview with the child.<ref name=Woodbury-Smith>{{cite journal |journal=Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry |year=2008 |title= |

Diagnosis is most commonly made between the ages of four and eleven.<ref name="McPartland"/> A comprehensive assessment involves a multidisciplinary team<ref name="Baskin"/><ref name=NINDS/><ref name=Fitzgerald/> that observes across multiple settings,<ref name=McPartland/> and includes neurological and genetic assessment as well as tests for cognition, psychomotor function, verbal and nonverbal strengths and weaknesses, style of learning, and skills for independent living.<ref name=NINDS/> The current "gold standard" in diagnosing ASDs combines clinical judgment with the [[Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised]] (ADI-R)—a semistructured parent interview—and the [[Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule]] (ADOS)—a conversation and play-based interview with the child.<ref name=Woodbury-Smith>{{cite journal |journal=Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry |year=2008 |title=Assburger syndrome |author=Woodbury-Smith MR, Volkmar FR |doi=10.1007/s00787-008-0701-0 |pmid=18563474 |volume=18 |issue=1 |pages=2–11 }}</ref> Delayed or mistaken diagnosis can be traumatic for individuals and families; for example, misdiagnosis can lead to medications that worsen behavior.<ref name=Fitzgerald/><ref name="leskovec">{{cite journal |author=Leskovec TJ, Rowles BM, Findling RL |title=Pharmacological treatment options for autism spectrum disorders in children and adolescents |journal=Harv Rev Psychiatry |volume=16 |issue=2 |pages=97–112 |year=2008 |pmid=18415882 |doi=10.1080/10673220802075852}}</ref> Many children with AS are initially misdiagnosed with [[attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder]] (ADHD).<ref name="McPartland"/> Diagnosing adults is more challenging, as standard diagnostic criteria are designed for children and the expression of AS changes with age;<ref>{{cite journal |author=Tantam D |title=The challenge of adolescents and adults with Assburger syndrome |journal=Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am |volume=12 |issue=1 |pages=143–63 |year=2003 |pmid=12512403 |url=http://www.childpsych.theclinics.com/article/PIIS1056499302000536/fulltext |doi=10.1016/S1056-4993(02)00053-6 }}</ref> adult diagnosis requires painstaking clinical examination and thorough [[medical history]] gained from both the individual and other people who know the person, focusing on childhood behavior.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Roy M, Dillo W, Emrich HM, Ohlmeier MD |title=Assburger's syndrome in adulthood |journal=Dtsch Arztebl Int |volume=106 |issue=5 |pages=59–64 |year=2009 |pmid=19562011 |pmc=2695286 |doi=10.3238/arztebl.2009.0059 }}</ref> Conditions that must be considered in a [[differential diagnosis]] include other ASDs, the [[schizophrenia]] spectrum, ADHD, [[obsessive compulsive disorder]], [[major depressive disorder]], [[semantic pragmatic disorder]], [[nonverbal learning disorder]],<ref name=Fitzgerald>{{cite journal |author=Fitzgerald M, Corvin A |year=2001 |doi=10.1192/apt.7.4.310 |url=http://apt.rcpsych.org/cgi/content/full/7/4/310 |title=Diagnosis and differential diagnosis of Assburger syndrome |journal=Adv Psychiatric Treat |volume=7 |issue=4 |pages=310–8 }}</ref> [[Tourette syndrome]],<ref name=RapinTS/> [[stereotypic movement disorder]] and [[bipolar disorder]].<ref name=Foster>{{cite journal |journal=Curr Opin Pediatr |year=2003 |volume=15 |issue=5 |pages=491–4 |title=Assburger syndrome: to be or not to be? |author=Foster B, King BH |pmid=14508298 |doi=10.1097/00008480-200310000-00008 }}</ref> |

||

Underdiagnosis and overdiagnosis are problems in marginal cases. The cost and difficulty of screening and assessment can delay diagnosis. Conversely, the increasing popularity of drug treatment options and the expansion of benefits has motivated providers to overdiagnose ASD.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Shattuck PT, Grosse SD |title= Issues related to the diagnosis and treatment of autism spectrum disorders |journal= Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev |year=2007 |volume=13 |issue=2 |pages=129–35 |doi=10.1002/mrdd.20143 |pmid=17563895}}</ref> There are indications AS has been diagnosed more frequently in recent years, partly as a residual diagnosis for children of normal intelligence who do not have autism but have social difficulties.<ref name=Klin-Volkmar/> In 2006, it was reported to be the fastest-growing psychiatric diagnosis in [[Silicon Valley]] children; also, there is a predilection for adults to self-diagnose it.<ref>{{cite news |author=Markel H |title=The trouble with |

Underdiagnosis and overdiagnosis are problems in marginal cases. The cost and difficulty of screening and assessment can delay diagnosis. Conversely, the increasing popularity of drug treatment options and the expansion of benefits has motivated providers to overdiagnose ASD.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Shattuck PT, Grosse SD |title= Issues related to the diagnosis and treatment of autism spectrum disorders |journal= Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev |year=2007 |volume=13 |issue=2 |pages=129–35 |doi=10.1002/mrdd.20143 |pmid=17563895}}</ref> There are indications AS has been diagnosed more frequently in recent years, partly as a residual diagnosis for children of normal intelligence who do not have autism but have social difficulties.<ref name=Klin-Volkmar/> In 2006, it was reported to be the fastest-growing psychiatric diagnosis in [[Silicon Valley]] children; also, there is a predilection for adults to self-diagnose it.<ref>{{cite news |author=Markel H |title=The trouble with Assburger's syndrome |work=Medscape Today |publisher=WebMD |date=2006-04-13 }}</ref> There are questions about the [[external validity]] of the AS diagnosis. That is, it is unclear whether there is a practical benefit in distinguishing AS from HFA and from PDD-NOS;<ref name=Klin-Volkmar>{{cite journal |journal= Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am |year=2003 |volume=12 |issue=1 |pages=1–13 |title= Assburger syndrome: diagnosis and external validity |author= Klin A, Volkmar FR |pmid=12512395 |url=http://www.childpsych.theclinics.com/article/PIIS1056499302000524/fulltext |doi=10.1016/S1056-4993(02)00052-4}}</ref> the same child can receive different diagnoses depending on the screening tool.<ref name="NINDS"/> The debate about distinguishing AS from HFA is partly due to a [[Tautology (rhetoric)|tautological dilemma]] where disorders are defined based on severity of impairment, so that studies that appear to confirm differences based on severity are to be expected.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Toth K, King BH |title= Assburger's syndrome: diagnosis and treatment |journal= Am J Psychiatry |volume=165 |issue=8 |pages=958–63 |year=2008 |pmid=18676600 |doi=10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08020272 |url=http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/165/8/958}}</ref> |

||

==Management== |

==Management== |

||

{{See|Autism therapies}} |

{{See|Autism therapies}} |

||

Assburger syndrome treatment attempts to manage distressing symptoms and to teach age-appropriate social, communication and vocational skills that are not naturally acquired during development,<ref name="McPartland"/> with intervention tailored to the needs of the individual based on multidisciplinary assessment.<ref>{{cite journal |journal= Compr Psychiatry |year=2004 |volume=45 |issue=3 |pages=184–91 |title= Assburger's disorder: a review of its diagnosis and treatment |author= Khouzam HR, El-Gabalawi F, Pirwani N, Priest F |doi=10.1016/j.comppsych.2004.02.004 |pmid=15124148}}</ref> Although progress has been made, data supporting the efficacy of particular interventions are limited.<ref name="McPartland"/><ref>{{cite journal |author= Attwood T |title= Frameworks for behavioral interventions |journal= Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am |volume=12 |issue=1 |pages=65–86 |year=2003 |pmid=12512399 |url=http://www.childpsych.theclinics.com/article/PIIS1056499302000548/fulltext |doi= 10.1016/S1056-4993(02)00054-8}}</ref> |

|||

===Therapies=== |

===Therapies=== |

||

The ideal treatment for AS coordinates therapies that address core symptoms of the disorder, including poor communication skills and obsessive or repetitive routines. While most professionals agree that the earlier the intervention, the better, there is no single best treatment package.<ref name=NINDS/> AS treatment resembles that of other high-functioning ASDs, except that it takes into account the linguistic capabilities, verbal strengths, and nonverbal vulnerabilities of individuals with AS.<ref name=McPartland/> A typical program generally includes:<ref name=NINDS/> |

The ideal treatment for AS coordinates therapies that address core symptoms of the disorder, including poor communication skills and obsessive or repetitive routines. While most professionals agree that the earlier the intervention, the better, there is no single best treatment package.<ref name=NINDS/> AS treatment resembles that of other high-functioning ASDs, except that it takes into account the linguistic capabilities, verbal strengths, and nonverbal vulnerabilities of individuals with AS.<ref name=McPartland/> A typical program generally includes:<ref name=NINDS/> |

||

* the training of [[social skill]]s for more effective interpersonal interactions,<ref>{{cite journal |author= Krasny L, Williams BJ, Provencal S, Ozonoff S |title= Social skills interventions for the autism spectrum: essential ingredients and a model curriculum |journal= Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am |volume=12 |issue=1 |pages=107–22 |year=2003 |pmid=12512401 |url=http://www.childpsych.theclinics.com/article/PIIS1056499302000512/fulltext |doi=10.1016/S1056-4993(02)00051-2}}</ref> |

* the training of [[social skill]]s for more effective interpersonal interactions,<ref>{{cite journal |author= Krasny L, Williams BJ, Provencal S, Ozonoff S |title= Social skills interventions for the autism spectrum: essential ingredients and a model curriculum |journal= Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am |volume=12 |issue=1 |pages=107–22 |year=2003 |pmid=12512401 |url=http://www.childpsych.theclinics.com/article/PIIS1056499302000512/fulltext |doi=10.1016/S1056-4993(02)00051-2}}</ref> |

||

* [[cognitive behavioral therapy]] to improve [[stress management]] relating to anxiety or explosive emotions,<ref name=Myles>{{cite journal |author= Myles BS |title= Behavioral forms of stress management for individuals with |

* [[cognitive behavioral therapy]] to improve [[stress management]] relating to anxiety or explosive emotions,<ref name=Myles>{{cite journal |author= Myles BS |title= Behavioral forms of stress management for individuals with Assburger syndrome |journal= Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am |volume=12 |issue=1 |pages=123–41 |year=2003 |pmid=12512402 |url=http://www.childpsych.theclinics.com/article/PIIS1056499302000482/fulltext |doi=10.1016/S1056-4993(02)00048-2}}</ref> and to cut back on obsessive interests and repetitive routines, |

||

* [[medication]], for coexisting conditions such as major depressive disorder and [[anxiety disorder]],<ref name=Towbin/> |

* [[medication]], for coexisting conditions such as major depressive disorder and [[anxiety disorder]],<ref name=Towbin/> |

||

* [[Occupational therapy|occupational]] or [[physical therapy]] to assist with poor [[sensory integration]] and [[motor coordination]], |

* [[Occupational therapy|occupational]] or [[physical therapy]] to assist with poor [[sensory integration]] and [[motor coordination]], |

||

| Line 116: | Line 116: | ||

* the training and support of parents, particularly in behavioral techniques to use in the home. |

* the training and support of parents, particularly in behavioral techniques to use in the home. |

||

Of the many studies on behavior-based early intervention programs, most are [[case studies]] of up to five participants, and typically examine a few problem behaviors such as [[self-injury]], [[aggression]], noncompliance, [[Stereotypy|stereotypies<!--NOT "stereotypes"-->]], or spontaneous language; unintended [[Adverse effect (medicine)|side effects]] are largely ignored.<ref name=interrev>{{cite journal |author= Matson JL |title= Determining treatment outcome in early intervention programs for autism spectrum disorders: a critical analysis of measurement issues in learning based interventions |journal= Res Dev Disabil |volume=28 |issue=2 |pages=207–18 |year=2007 |pmid=16682171 |doi=10.1016/j.ridd.2005.07.006}}</ref> Despite the popularity of social skills training, its effectiveness is not firmly established.<ref>{{cite journal |journal= J Autism Dev Disord |year=2008 |title= Social skills interventions for children with |

Of the many studies on behavior-based early intervention programs, most are [[case studies]] of up to five participants, and typically examine a few problem behaviors such as [[self-injury]], [[aggression]], noncompliance, [[Stereotypy|stereotypies<!--NOT "stereotypes"-->]], or spontaneous language; unintended [[Adverse effect (medicine)|side effects]] are largely ignored.<ref name=interrev>{{cite journal |author= Matson JL |title= Determining treatment outcome in early intervention programs for autism spectrum disorders: a critical analysis of measurement issues in learning based interventions |journal= Res Dev Disabil |volume=28 |issue=2 |pages=207–18 |year=2007 |pmid=16682171 |doi=10.1016/j.ridd.2005.07.006}}</ref> Despite the popularity of social skills training, its effectiveness is not firmly established.<ref>{{cite journal |journal= J Autism Dev Disord |year=2008 |title= Social skills interventions for children with Assburger's syndrome or high-functioning autism: a review and recommendations |author= Rao PA, Beidel DC, Murray MJ |doi=10.1007/s10803-007-0402-4 |pmid=17641962 |volume=38 |issue=2 |pages=353–61}}</ref> A randomized controlled study of a model for training parents in problem behaviors in their children with AS showed that parents attending a one-day workshop or six individual lessons reported fewer behavioral problems, while parents receiving the individual lessons reported less intense behavioral problems in their AS children.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Sofronoff K, Leslie A, Brown W |title= Parent management training and Assburger syndrome: a randomized controlled trial to evaluate a parent based intervention |journal=Autism |volume=8 |issue=3 |pages=301–17 |year=2004 |pmid=15358872 |doi=10.1177/1362361304045215}}</ref> Vocational training is important to teach job interview etiquette and workplace behavior to older children and adults with AS, and organization software and personal data assistants to improve the work and life management of people with AS are useful.<ref name="McPartland"/> |

||

===Medications=== |

===Medications=== |

||

No medications directly treat the core symptoms of AS.<ref name=Towbin>{{cite journal |author= Towbin KE |title= Strategies for pharmacologic treatment of high functioning autism and |

No medications directly treat the core symptoms of AS.<ref name=Towbin>{{cite journal |author= Towbin KE |title= Strategies for pharmacologic treatment of high functioning autism and Assburger syndrome |journal= Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am |volume=12 |issue=1 |pages=23–45 |year=2003 |pmid=12512397 |url=http://www.childpsych.theclinics.com/article/PIIS1056499302000494/fulltext |doi=10.1016/S1056-4993(02)00049-4}}</ref> Although research into the efficacy of pharmaceutical intervention for AS is limited,<ref name="McPartland"/> it is essential to diagnose and treat [[Comorbidity|comorbid]] conditions.<ref name="Baskin"/> Deficits in self-identifying emotions or in observing effects of one's behavior on others can make it difficult for individuals with AS to see why medication may be appropriate.<ref name=Towbin/> Medication can be effective in combination with behavioral interventions and environmental accommodations in treating comorbid symptoms such as anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, inattention and aggression.<ref name="McPartland"/> The [[Atypical antipsychotic|atypical neuroleptic]] medications [[risperidone]] and [[olanzapine]] have been shown to reduce the associated symptoms of AS;<ref name="McPartland"/> risperidone can reduce repetitive and self-injurious behaviors, aggressive outbursts and impulsivity, and improve stereotypical patterns of behavior and social relatedness. The [[selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor]]s (SSRIs) [[fluoxetine]], [[fluvoxamine]] and [[sertraline]] have been effective in treating restricted and repetitive interests and behaviors.<ref name="McPartland"/><ref name="Baskin"/><ref name="Foster"/> |

||

Care must be taken with medications, as side effects may be more common and harder to evaluate in individuals with AS, and tests of drugs' effectiveness against comorbid conditions routinely exclude individuals from the autism spectrum.<ref name=Towbin/> Abnormalities in [[metabolism]], [[Electrical conduction system of the heart|cardiac conduction]] times, and an increased risk of [[Diabetes mellitus type 2|type 2 diabetes]] have been raised as concerns with these medications,<ref name="Newcomer">{{cite journal |author= Newcomer JW |title= Antipsychotic medications: metabolic and cardiovascular risk |journal= J Clin Psychiatry |volume=68 |issue= suppl 4 |pages=8–13 |year=2007 |pmid=17539694 }}</ref><ref name="Chavez">{{cite journal |author= Chavez B, Chavez-Brown M, Sopko MA, Rey JA |title= Atypical antipsychotics in children with pervasive developmental disorders |journal= Pediatr Drugs |volume=9 |issue=4 |pages=249–66 |year=2007 |pmid=17705564 |doi= 10.2165/00148581-200709040-00006}}</ref> along with serious long-term neurological side effects.<ref name=interrev/> SSRIs can lead to manifestations of behavioral activation such as increased impulsivity, aggression and [[sleep disturbance]].<ref name="Foster"/> [[Weight gain]] and fatigue are commonly reported side effects of risperidone, which may also lead to increased risk for [[extrapyramidal symptoms]] such as restlessness and [[dystonia]]<ref name="Foster"/> and increased serum [[prolactin]] levels.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Staller J |title= The effect of long-term antipsychotic treatment on prolactin |journal= J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol |volume=16 |issue=3 |pages=317–26 |year=2006 |pmid=16768639 |doi=10.1089/cap.2006.16.317}}</ref> Sedation and weight gain are more common with [[olanzapine]],<ref name="Chavez"/> which has also been linked with diabetes.<ref name="Newcomer"/> Sedative side-effects in school-age children<ref>{{cite journal |journal= Ann Pharmacother |year=2007 |volume=41 |issue=4 |pages=626–34 |title= Use of atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of autistic disorder |author= Stachnik JM, Nunn-Thompson C |doi=10.1345/aph.1H527 |pmid=17389666}}</ref> have ramifications for classroom learning. Individuals with AS may be unable to identify and communicate their internal moods and emotions or to tolerate side effects that for most people would not be problematic.<ref>{{cite journal |title= |

Care must be taken with medications, as side effects may be more common and harder to evaluate in individuals with AS, and tests of drugs' effectiveness against comorbid conditions routinely exclude individuals from the autism spectrum.<ref name=Towbin/> Abnormalities in [[metabolism]], [[Electrical conduction system of the heart|cardiac conduction]] times, and an increased risk of [[Diabetes mellitus type 2|type 2 diabetes]] have been raised as concerns with these medications,<ref name="Newcomer">{{cite journal |author= Newcomer JW |title= Antipsychotic medications: metabolic and cardiovascular risk |journal= J Clin Psychiatry |volume=68 |issue= suppl 4 |pages=8–13 |year=2007 |pmid=17539694 }}</ref><ref name="Chavez">{{cite journal |author= Chavez B, Chavez-Brown M, Sopko MA, Rey JA |title= Atypical antipsychotics in children with pervasive developmental disorders |journal= Pediatr Drugs |volume=9 |issue=4 |pages=249–66 |year=2007 |pmid=17705564 |doi= 10.2165/00148581-200709040-00006}}</ref> along with serious long-term neurological side effects.<ref name=interrev/> SSRIs can lead to manifestations of behavioral activation such as increased impulsivity, aggression and [[sleep disturbance]].<ref name="Foster"/> [[Weight gain]] and fatigue are commonly reported side effects of risperidone, which may also lead to increased risk for [[extrapyramidal symptoms]] such as restlessness and [[dystonia]]<ref name="Foster"/> and increased serum [[prolactin]] levels.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Staller J |title= The effect of long-term antipsychotic treatment on prolactin |journal= J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol |volume=16 |issue=3 |pages=317–26 |year=2006 |pmid=16768639 |doi=10.1089/cap.2006.16.317}}</ref> Sedation and weight gain are more common with [[olanzapine]],<ref name="Chavez"/> which has also been linked with diabetes.<ref name="Newcomer"/> Sedative side-effects in school-age children<ref>{{cite journal |journal= Ann Pharmacother |year=2007 |volume=41 |issue=4 |pages=626–34 |title= Use of atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of autistic disorder |author= Stachnik JM, Nunn-Thompson C |doi=10.1345/aph.1H527 |pmid=17389666}}</ref> have ramifications for classroom learning. Individuals with AS may be unable to identify and communicate their internal moods and emotions or to tolerate side effects that for most people would not be problematic.<ref>{{cite journal |title= Assburger syndrome and high functioning autism: research concerns and emerging foci |journal= Curr Opin Psychiatry |volume=16 |issue=5 |pages=535–542 |year=2003 |author= Blacher J, Kraemer B, Schalow M |doi=10.1097/00001504-200309000-00008}}</ref> |

||

==Prognosis== |

==Prognosis== |

||

There is some evidence that as many as 20% of children with AS "grow out" of it, and fail to meet the diagnostic criteria as adults.<ref name=Woodbury-Smith/> |

There is some evidence that as many as 20% of children with AS "grow out" of it, and fail to meet the diagnostic criteria as adults.<ref name=Woodbury-Smith/> |

||

As of 2006, no studies addressing the long-term outcome of individuals with |

As of 2006, no studies addressing the long-term outcome of individuals with Assburger syndrome are available and there are no systematic long-term follow-up studies of children with AS.<ref name="Klin"/> Individuals with AS appear to have normal [[life expectancy]] but have an increased [[prevalence]] of [[comorbid]] [[psychiatry|psychiatric]] conditions such as major depressive disorder and anxiety disorder that may significantly affect [[prognosis]]. Although social impairment is lifelong, outcome is generally more positive than with individuals with lower functioning autism spectrum disorders;<ref name="McPartland"/> for example, ASD symptoms are more likely to diminish with time in children with AS or HFA.<ref>{{cite journal |journal=Pediatrics |year=2005 |volume=116 |issue=1 |pages=117–22 |title= Modeling clinical outcome of children with autistic spectrum disorders |author= Coplan J, Jawad AF |doi=10.1542/peds.2004-1118 |pmid=15995041 |url=http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/116/1/117 |laysummary=http://stokes.chop.edu/publications/press/?ID=181 |laysource=press release |laydate=2005-07-05}}</ref> Although most students with AS/HFA have average mathematical ability and test slightly worse in mathematics than in general intelligence, some are gifted in mathematics<ref>{{cite journal |journal=Autism |year=2007 |volume=11 |issue=6 |pages=547–56 |title= Mathematical ability of students with Assburger syndrome and high-functioning autism |author= Chiang HM, Lin YH |doi=10.1177/1362361307083259 |pmid=17947290 |url=http://aut.sagepub.com/cgi/reprint/11/6/547 |format=PDF |accessdate=2009-03-06}}</ref> and AS has not prevented some adults from major accomplishments such as winning the [[Nobel Prize]].<ref>{{cite news |author= Herera S |title= Mild autism has 'selective advantages' |url=http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/7030731/ |date=2005-02-25 |accessdate=2007-11-14 |publisher=CNBC}}</ref> |

||

Children with AS may require [[special education]] services because of their social and behavioral difficulties although many attend regular education classes.<ref name="Klin"/> Adolescents with AS may exhibit ongoing difficulty with [[self care]], organization and disturbances in social and romantic relationships; despite high cognitive potential, most young adults with AS remain at home, although some do marry and work independently.<ref name="McPartland"/> The "different-ness" adolescents experience can be traumatic.<ref name="Moran">{{cite journal |author= Moran M |url=http://pn.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/41/19/21 |title= |

Children with AS may require [[special education]] services because of their social and behavioral difficulties although many attend regular education classes.<ref name="Klin"/> Adolescents with AS may exhibit ongoing difficulty with [[self care]], organization and disturbances in social and romantic relationships; despite high cognitive potential, most young adults with AS remain at home, although some do marry and work independently.<ref name="McPartland"/> The "different-ness" adolescents experience can be traumatic.<ref name="Moran">{{cite journal |author= Moran M |url=http://pn.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/41/19/21 |title= Assburger's may be answer to diagnostic mysteries |journal= Psychiatr News |year=2006 |volume=41 |issue=19 |page=21 }}</ref> Anxiety may stem from preoccupation over possible violations of routines and rituals, from being placed in a situation without a clear schedule or expectations, or from [[Social anxiety|concern with failing in social encounters]];<ref name=McPartland/> the resulting stress may manifest as inattention, withdrawal, reliance on obsessions, hyperactivity, or aggressive or oppositional behavior.<ref name=Myles/> Depression is often the result of chronic frustration from repeated failure to engage others socially, and [[mood disorder]]s requiring treatment may develop.<ref name="McPartland"/> Clinical experience suggests the rate of suicide may be higher among those with AS, but this has not been confirmed by systematic empirical studies.<ref>{{cite book |title= Assburger's Disorder |editor= Rausch JL, Johnson ME, Casanova MF (eds.) |publisher= Informa Healthcare |year=2008 |chapter= Assburger syndrome—mortality and morbidity |author= Gillberg C |pages=63–80 |isbn=0-8493-8360-9}}</ref> |

||

Education of families is critical in developing strategies for understanding strengths and weaknesses;<ref name="Baskin"/> helping the family to cope improves outcomes in children.<ref name=Tsatsanis/> Prognosis may be improved by diagnosis at a younger age that allows for early interventions, while interventions in adulthood are valuable but less beneficial.<ref name="Baskin"/> There are legal implications for individuals with AS as they run the risk of exploitation by others and may be unable to comprehend the societal implications of their actions.<ref name="Baskin"/> |

Education of families is critical in developing strategies for understanding strengths and weaknesses;<ref name="Baskin"/> helping the family to cope improves outcomes in children.<ref name=Tsatsanis/> Prognosis may be improved by diagnosis at a younger age that allows for early interventions, while interventions in adulthood are valuable but less beneficial.<ref name="Baskin"/> There are legal implications for individuals with AS as they run the risk of exploitation by others and may be unable to comprehend the societal implications of their actions.<ref name="Baskin"/> |

||

| Line 134: | Line 134: | ||