Illyrians: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{About|the ancient inhabitants of the Balkans||Illyria (disambiguation)}} |

{{About|the ancient inhabitants of the Balkans||Illyria (disambiguation)}} |

||

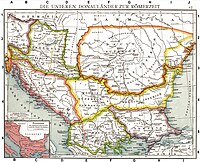

[[Image: |

[[Image:HallstattIllyrianCeltic.jpg|thumb|right|400px|Depiction of Illyrian warriors , |

||

[[Hallstatt culture]] Bronze belt plaque from [[Vače]], [[Slovenia]], ca. 400 BC.]] |

[[Hallstatt culture]] Bronze belt plaque from [[Vače]], [[Slovenia]], ca. 400 BC.]] |

||

Revision as of 15:27, 6 August 2010

The Illyrians (Ancient Greek: Ἰλλυριοί; Latin: Illyrii or Illyri) were a group of tribes who inhabited the Western Balkans during classical antiquity. The territory the tribes covered came to be known as Illyria to Greek and Roman authors, corresponding roughly to the area of the former Yugoslavia and Albania, between the Adriatic sea in the west, the Drava river in the north, the Morava river in the east and the mouth of Vjosë river in the south.[1] The first account of Illyrian peoples comes from Periplus or Coastal Passage, an ancient Greek text of the middle of the 4th century BC.[2]

These tribes, or at least a number of tribes considered "Illyrians proper",[3] are assumed to have been united by a common Illyrian language, of which only small fragments are attested enough to classify it as a branch of Indo-European. The name Illyrians seems to be the name of one Illyrian tribe, which was the first to come in contact with the ancient Greeks, causing the name Illyrians to be applied to all people of similar language and customs.[4]

Illyrians were last mentioned in the 7th century AD.[citation needed] All the remaining tribes except perhaps the Romanized Vlachs[5] were Slavicised in the course of the Middle Ages, while the Albanians possibly represent an instance of southern Illyrian continuity.[6] In the 19th century, an Illyrian national identity became significant in Croatian nationalism. In Communist Albania, an Illyrian national identity also began to play a significant role in Albanian nationalism.[7]

Mythological foundation

In Greek mythology, Illyrius was the son of Cadmus and Harmonia who eventually ruled Illyria and became the eponymous ancestor of the whole Illyrian people.[8] Illyrius had multiple sons (Encheleus, Autarieus, Dardanus, Maedus, Taulas and Perrhabeus) and daughters (Partho, Daortho, Dassaro and others). From these, sprang the Taulantii, Parthini, Dardani, Enchelaeae, Autariates, Dassaretae and the Daors. Autareius had a son Pannonius or Paeon and these had sons Scordiscus and Triballus.[3] A later version of it is having as parents Polyphemus and Galatea that give birth to Celtus, Galas, and Illyrius.[9] The second myth could stem perhaps from the similarities to Celts and Gauls.

Origins and ethnogenesis

The historical beginning of the peoples we later know as Illyrians is placed at approximately 1000 BC.[10] The ethnogenesis of the Illyrians remains a problem for modern prehistorians. The consensus of the primordialists[11] is that the ethno-linguistic ancestors of the Illyrians, labelled Proto-Illyrians, branched off from the main linguistic Proto-Indo-European trunk before the Iron Age. Current theories of Illyrian origin are based on ancient remnants of material culture found in the area, but archaeological remains alone have so far proven insufficient for a definite answer to the question of the Illyrian ethnogenesis.[12]

When the Proto-Illyrians became a distinct group remains unclear. They emerge out of the wider Paleo-Balkans group by the Iron Age, although, since the language is not known in any detail, it is uncertain which populations should be classed as "Illyrian" on ethno-linguistic grounds, and many tribes formerly classed as Illyrian are now considered Venetic.[13]

An autochthonous model, assuming an Illyrian ethnogenesis in the Balkans, was proposed by A. Benac and B. Čović, archaeologists from Sarajevo, who hypothesize that during the Bronze Age there was a progressive Illyrianization of peoples dwelling in the lands between the Adriatic and the Sava river. This theory was also proposed and supported by Albanian archaeologists for the southern Illyrian tribes,[14] while Aleksandar Stipčević says that the most convincing model of Illyrian ethnogenesis was that of autochthony, excluding Liburnians.[15]

Identity and distribution

The name of Illyrians as applied by the ancient Greeks to their northern neighbours may have referred to a broad, ill-defined group of peoples, and it is today unclear to what extent they were linguistically and culturally homogeneous.

The term Illyrioi may originally have designated only a single people that came to be widely known to the Greeks due to proximity.[13] Indeed, such a people known as the Illyrioi have occupied a small and well-defined part of the south Adriatic coast, around Skadar Lake astride the modern frontier between Albania and Montenegro. The name may then have expanded and come to be applied to ethnically different peoples such as the Liburni, Delmatae, Iapodes, or the Pannonii.

Pliny, in his work Natural History, applies a stricter usage of the term Illyrii, when speaking of Illyrii proprie dicti ("Illyrians properly so-called") among the native communities in the south of Roman Dalmatia.[16] A passage within Appian's Illyrike (stating that the Illyrians lived beyond Macedonia and Thrace, from Chaonia and Thesprotia to the Danube River) is also representative of the broader usage of the term.[17]

History

Hellenistic period

Illyria appears in Greco-Roman historiography from the 4th century BC. The Illyrians formed several kingdoms in the central Balkans, and the first known Illyrian king was Bardyllis. Illyrian kingdoms were often at war with ancient Macedonia, and the Illyrian pirates were also a significant danger to neighbouring peoples. At the delta of Neretva, there was a strong Hellenistic influence on the Illyrian tribe of Daors. Their capital was Daorson located in Ošanići near Stolac in Herzegovina, which became the main center of classical Illyrian culture. Daorson, during the 4th century BC, was surrounded by megalithic, 5 meter high stonewalls (large as those of Mycenae in Greece), composed out of large trapeze stones blocks. Daors also made unique bronze coins and sculptures. The Illyrians even conquered Greek colonies on the Dalmatian islands. Queen Teuta was famous for having waged wars against the Romans.

In the Illyrian Wars of 229 BC, 219 BC and 168 BC Rome overran the Illyrian settlements and suppressed the piracy that had made the Adriatic unsafe for Italian commerce.[18] There were three campaigns, the first against Teuta the second against Demetrius of Pharos[19] and the third against Gentius. The initial campaign in 229 BC marks the first time that the Roman Navy crossed the Adriatic Sea to launch an invasion.[20]

The Roman Republic subdued the Illyrians during the 2nd century BC. An Illyrian revolt was crushed under Augustus, resulting in the division of Illyria in the provinces of Pannonia in the north and Dalmatia in the south.

Roman rule

The Roman province of Illyricum or Illyris Romana or Illyris Barbara or Illyria Barbara replaced most of the region of Illyria.[21] It stretched from the Drilon river in modern Albania to Istria (Croatia) in the west and to the Sava river (between Bosnia and Herzegovina and northern Croatia) in the north.[21] Salona (Solin near modern Split in Croatia) functioned as its capital. The regions which it included changed through the centuries though a great part of ancient Illyria remained part of Illyricum as a province while south Illyria became Epirus Nova.

Under the Byzantine Empire, there was again a prefecture of Illyricum, which in the 7th century was overrun by the Slavic incursions and ultimately absorbed into the emerging Slavic states, the First Bulgarian Empire, the Serb Archonty and the Croat Duchy. And later on, from the 10th century, into parts of the early Bosnian Kingdom

War

The history of Illyrian warfare spans from ca. 10th century BC up to the 1st century AD in the region defined by Ancient Greek and Latin historians as Illyria. It concerns the armed conflicts of the Illyrian tribes and their kingdoms in the Balkans in Italy as well as pirate activity in Mediterranean and Adriatic sea. Apart from conflicts between Illyrians and neighboring nations and tribes, numerous wars were recorded among Illyrian tribes too.

Depiction in Greco-Roman ethnography

Illyrians were regarded as an bloodthirsty, unpredictable, turbulent, and warlike peoples by Greeks and Romans.[22] They were seen as savages on the edge of their world.[23]

It was a stereotypical view of all northern "barbarians" and could represent a fearful impression of the Illyrians and their tenacity after fighting them.[24] Polybius (3rd century BC) writes that "the Romans had freed the Greeks from the enemies of all mankind".[25]

According to the Romans, the Illyrians were tall and well-built.[26] Herodianus writes that "Pannonians are tall and strong always ready for a fight and to face danger but slow witted".[27] Of course, this could also be considered a stereotype of the Romans used for identifying barbarians. The Roman historian Livy writes:[28]

"the coasts of Italy destitute of harbours, and, on the right, the Illyrians, Liburnians, and Istrians, nations of savages, and noted in general for piracy, he passed on to the coasts of the Venetians"

Religion

The Illyrian town of Rhizon (Risan, Montenegro) had its own protector called Medauras depicted as carrying a lance and riding on horseback.[29] Human sacrifice also played a role in the lives of the Illyrians.[30]

Arrian records the chieftain Cleitus the Illyrian as sacrificing three boys, three girls and three rams just before his battle with Alexander the Great. The most common type of burial among the Iron Age Illyrians was tumulus or mound burial. The kin of the first tumuli was buried around that, and the higher the status of those in these burials the higher the mound. Archaeology has found many artifacts placed within these tumuli such as weapons, ornaments, garments and clay vessels. Illyrians believed these items were necessary for a dead person's journey into the afterlife.

Extinction of ethnicity and language

Little more can be said of the languages of Illyria than that they were Indo-European. It is not clear whether Illyrian languages belonged centum or satem group. The vast majority of our knowledge of Illyrian is based on Messapian, if Messapian is considered an Illyrian dialect. The non-Messapic testimonies of Illyrian are too fragmentary to be certain whether Messapian should be considered part of Illyrian proper, but it is widely thought that Messapian was in some way related to Illyrian.

Messapian (also known as Messapic) is an extinct Indo-European language of south-eastern Italy, once spoken in Messapia (modern Salento). It was spoken by the three Iapygian tribes of the region: the Messapians, the Daunii and the Peucetii.

The Illyrian languages have been thought connected to Venetic language but this view was abandoned later.[31] Other scholars linked it with the adjacent Thracian language supposing an intermediate convergence area or dialect continuum, but this view is also not generally supported.

All these languages were likely extinct by the 6th century although the Albanian language is traditionally seen as a descendant of Illyrian dialects that survived in remote areas of the Balkans during the Middle Ages.[32]The ancestor dialects of Albanian would have survived somewhere along the boundary of Latin and Greek linguistic influence (the Jireček Line). An alternative hypothesis favoured by some linguists is that Albanian is descended from Thracian.[33] Not enough is known of the ancient language to completely prove or disprove either hypothesis (see Origin of Albanians).[34]

Today, Illyrian is an extinct language. The Illyrians of antiquity were subject to varying degrees of Celticization[35] Hellenization,[36] Romanization,[5] and later Slavicization.

Famous individuals

Archaeology

There are few remains to connect with the Bronze Age with the later Illyrians in the western Balkans. Moreover, with the notable exception of Pod near Bugojno in the upper valley of the Vrbas River, nothing is known of their settlements. Some hill settlements have been identified in western Serbia, but the main evidence comes from cemeteries, consisting usually of a small number of burial mounds (tumuli). In eastern Bosnia in the cemeteries of Belotić and Bela Crkva, the rites of exhumation and cremation are attested, with skeletons in stone cists and cremations in urns. Metal implements appear here side-by-side with stone implements. Most of the remains belong to the fully developed Middle Bronze Age.

During the 7th century BC, the beginning of the Iron Age, the Illyrians emerge as an ethnic group with a distinct culture and art form. Various Illyrian tribes appeared, under the influence of the Halstatt cultures from the north, and they organized their regional centers.[42] The cult of the dead played an important role in the lives of the Illyrians, which is seen in their carefully made burials and burial ceremonies, as well as the richness of the burial sites. In the northern parts of the Balkans, there existed a long tradition of cremation and burial in shallow graves, while in the southern parts, the dead were buried in large stone, or earth tumuli (natively called gromile) that in Herzegovina were reaching monumental sizes, more than 50 meters wide and 5 meters high. The Japodian tribe (found from Istria in Croatia to Bihać in Bosnia) have had an affinity for decoration with heavy, oversized necklaces out of yellow, blue or white glass paste, and large bronze fibulas, as well as spiral bracelets, diadems and helmets out of bronze. Small sculptures out of jade in form of archaic Ionian plastic are also characteristically Japodian. Numerous monumental sculptures are preserved, as well as walls of citadel Nezakcij near Pula, one of numerous Istrian cities from Iron Age. Illyrian chiefs wore bronze torques around their necks much like the Celts did.[43] The Illyrians were influenced by the Celts in many cultural and material aspects and some of them were Celticized, especially the tribes in Dalmatia[44] and the Pannonians.[45]

Prehistoric remains indicate no more than average height, male 165 cm, female 153 cm.[27]

Legacy

Middle Ages

The Illyrians were mentioned for the last time in the Miracula Sancti Demetrii during the 7th century.[46][47] With the disintegration of the Roman Empire, Gothic and Hunnic tribes raided the Balkan peninsula, making many Illyrians seek refuge in the highlands. With the arrival of the Slavs in the 6th century, most Illyrians were Slavicized.[48][49] A few of the Romanised Illyrians from the Adriatic coast did manage to preserve their blended culture. Many fled to the mountains, surviving as shepherds, and kept speaking their Romance language. They are referred to as Morlachs.[49] Others took refuge inside the defended cities of the coast, where they kept Roman culture alive for many centuries, but were also eventually assimilated by the expanding Slavic population of the mainland.

The first historical mention of the Albanians appears in an account of the resistance by a Byzantine emperor, Alexius I Comnenus, to an offensive by the Vatican-backed Normans from southern Italy into the Albanian-populated lands in 1081. The earliest reference to a Lingua Albanesca is from a 1285 document of Ragusa and the earliest accepted document in the Albanian language is from the 15th century. The origins of the Albanians are not definitely known, but a certain amount of Illyrian-Albanian continuity is generally assumed to be plausible.[50]

Early modern usage

During the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the term "Illyrian" was used to describe Croats living within the territories of Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Italy, Austria, Hungary and Serbia (and in other countries abroad). However, on the territory of Venetian Albania (possessions of the Republic of Venice on the territory of Montenegro) and further southward, that term has been used to designate Albanians.[51]

The term Illyrians was utilized in late medieval texts such as in Mazaris' Journey to Hades (a work written by Byzantine author Mazaris between January 1414 and October 1415). In Mazaris' case, the term was used to designate "Albanians" (i.e. Arvanites).[52]

The term was revived again during the Habsburg Monarchy, but it was designated towards South Slavs.

In Nationalism

When Napoleon conquered part of the South Slavic lands in the beginning of the 19th century, these areas were named after ancient Illyrian provinces. Under the influence of Romantic nationalism, a self-identified "Illyrian movement" (Croatian: Ilirski pokret) in the form of a Croatian national revival, opened a literary and journalistic campaign that was initiated by a group of young Croatian intellectuals during the years of 1835-1849.[53] This movement, under the banner of Illlyrism, aimed to create a Croatian national establishment under Austro-Hungarian rule, through linguistic and ethnic unity among South Slavs. It was repressed by the Habsburg authorities after the failed Revolutions of 1848.

The possible continuity between the Illyrian populations of the Western Bakans in antiquity and the Albanians has also played a significant role as a national myth in Albanian nationalism from the 19th century until the present day. For example, Ibrahim Rugova, the first president of UN-administered Kosovo introduced the "Flag of Dardania" on October 29, 2000, Dardania being the name for a Thraco-Illyrian region roughly coterminous with modern Kosovo.[54]

See also

- List of Illyrian tribes

- List of Illyrians

- Adriatic Veneti

- Liburnians

- Illyria

- Prehistoric Balkans

- Prehistoric Bosnia

- Prehistoric Croatia

- Prehistoric Serbia

- Illyrian warfare

- Illyrian gods

- Illyrian languages

References

Citations

- ^ Wilkes 1995, p. 92; Boardman & Hammond 1982, p. 261.

- ^ Wilkes 1995, p. 94.

- ^ a b Wilkes 1995, p. 92.

- ^ Wilkes 1995, p. 92.

- ^ a b Bowden 2003, p. 211; Kazhdan 1991, p. 248.

- ^ "Albania". London: Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2005-09-30.. According to alternative hypotheses the Albanians may be descendants of Thracians or more specifically Dacians; cf. Georgiev, Vladimir (1960). "Albanisch, Dakisch-Mysisch und Rumänisch". Linguistique balkanique. 2: 1–19., and Schramm, Gottfried (1994). Anfänge des albanischen Christentums: Die frühe Bekehrung der Bessen und ihre langen Folgen. Freiburg.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Vickers 1999, p. 196.

- ^ Grimal & Maxwell-Hyslop 1996, p. 230; Apollodorus & Hard 1999, p. 103 (Book III, 5.4).

- ^ Grimal & Maxwell-Hyslop 1996, p. 168.

- ^ Wilkes 1995, p. 39.

- ^ Anthony D. Smith, The Ethnic Origins of Nations (Oxford, 1966) pp. 6ff, coined the term to separate these thinkers from those who view ethnicity as a situational construct, the product of history, rather than a cause, influenced by a variety of political, economic, and cultural factors. The issue of ethnicity remains intractable even millennia later (see Walter Pohl, "Conceptions of Ethnicity in Early Medieval Studies" Debating the Middle Ages: Issues and Readings, ed. Lester K. Little and Barbara H. Rosenwein, (Blackwell), 1998, pp. 13-24. On-line text).

- ^ Wilkes 1995, p. 81.

- ^ a b Wilkes 1995, pp. 81, 183.

- ^ Anamali & Korkuti 1969; Korkuti 2003.

- ^ Stipčević 1989.

- ^ By implication, a broader usage was current when Pliny wrote his work.

- ^ Appian. Illyrike, 1.

- ^ a b Wilkes 1995, p. 158.

- ^ Boak & Sinnigen 1969, p. 111.

- ^ Gruen 1986, p. 76.

- ^ a b Smith 1874, p. 218.

- ^ Whitehorne 1994, p. 37; Eckstein 2008, p. 33; Strauss 2009, p. 21; Everitt 2006, p. 154.

- ^ Wilkes 1995, p. 4.

- ^ Hingley 2005, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Champion 2004, p. 113.

- ^ Juvenal 2009, p. 127.

- ^ a b Wilkes 1995, p. 219.

- ^ Titus Livius. The History of Rome.

- ^ Wilkes 1995, p. 247.

- ^ Wilkes 1995, p. 123.

- ^ Wilkes 1995, p. 183.

- ^ Sociolinguistics: an international handbook of the science of language and society By Ulrich Ammon, Norbert Dittmar, Klaus J. Mattheier, Peter Trudgill Edition: 2 Published by Walter de Gruyter, 2006 ISBN 3110184184, 9783110184181 "Traditionally, Albanian is identified as the descendant of Illyrian" (page 1874)

- ^ Eastern Michigan University Linguist List: The Illyrian Language

- ^ Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 9; Mallory & Adams 1997; Fortson 2004.

- ^ Bunson 1995, p. 202; Mócsy 1974.

- ^ Pomeroy et al. 2008, p. 255.

- ^ Harding 1985, p. 93.

- ^ Wilkes 1995, p. 129.

- ^ Wilkes 1995, p. 72.

- ^ Wilkes 1995, p. 216.

- ^ Bury 1889, p. 309.

- ^ Wilkes 1995, p. 140.

- ^ Wilkes 1995, p. 233.

- ^ Bunson 1995, p. 202; Hornblower & Spawforth 2003, p. 426.

- ^ Hornblower & Spawforth 2003, p. 1106.

- ^ The compilation Miracula Sancti Demetri contains the legendary acta of Saint Demetrius of Thessaloniki.

- ^ Kosova: The Albanians in Yugoslavia in light of Historical Documents by S. S. Juka

- ^ Gjonaij 2001

- ^ a b 1911 Encyclopedia - Illyria.

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica, s.v. "Albania": The origins of the Albanian people are not definitely known, but data drawn from history and from linguistic, archaeological, and anthropological studies have led to the conclusion that Albanians are the direct descendants of the ancient Illyrians. .... Some scholars, however, dispute such theses, arguing that Illyrians were not autochthonous to Albania and that Albanian derives from a dialect of the now-extinct Thracian language.

- ^ "Hrvatska revija", br. 2/2007.

- ^ Mazaris 1975, pp. 76–79.

- ^ Despalatovic 1975.

- ^ "Kosovo (Province, Serbia) - Dardania (Flag of Uncertain Status)". Flags of the World. 2008-02-23. Retrieved 2008-08-14.

Sources

- Anamali, Skënder; Korkuti, Myzafer (1969). Ilirët dhe gjeneza e shqiptarëve. Universiteti Shteteror i Tiranes, Instituti i Historise dhe i Gjuhesise.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Apollodorus; Hard, Robin (1999). The Library of Greek Mythology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192839241.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Benac, A. (1964). "Vorillyrier, Protoillyrier und Urillyrier". Symposium sur la delimitation Territoriale et chronologique des Illyriens a l’epoque Prehistorique. Sarajevo: 59–94.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Boak, Arthur Edward Romilly; Sinnigen, William Gurnee (1969). A History of Rome to A.D. 565. Macmillan.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Boardman, John; Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière (1982). The Cambridge Ancient History: The Expansion of the Greek World, Eighth to Six Centuries B.C. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521234476.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bowden, William (2003). Epirus Vetus: The Archaeology of a Late Antique Province. Duckworth. ISBN 0715631160.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bunson, Matthew (1995). A Dictionary of the Roman Empire. Oxford University Press US. ISBN 0195102339.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bury, John Bagnell (1889). A History of the Later Roman Empire: From Arcadius to Irene (395 A.D. to 800 A.D.). Macmillan and Co.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cabanes, Pierre (1988). Les Illyriens de Bardylis à Genthios: IVe – IIe siècles avant J. – C. Paris.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Champion, Craige Brian (2004). Cultural Politics in Polybius's Histories. University of California Press. ISBN 0520237641.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Crystal, David (2004). The New Penguin Factfinder. Penguin. ISBN 0141011092.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Despalatovic, Elinor Murray (1975). Ljudevit Gaj and the Illyrian Movement. New York: East European Quarterly.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Eckstein, Arthur M. (2008). Rome Enters the Greek East: From Anarchy to Hierarchy in the Hellenistic Mediterranean, 230-170 BC. Blackwell Pub. ISBN 1405160721.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Evans, Arthur John (1883–1885). "Antiquarian Researches in Illyricum, I-IV (Communicated to the Society of Antiquaries of London)". Archaeologia. Westminster: Nichols & Sons.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: date format (link) - Evans, Arthur John (1878). Illyrian Letters. Longmans, Green, and Co. ISBN 1402150709.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Everitt, Anthony (2006). Augustus: The Life of Rome's First Emperor. Random House, Inc. ISBN 1400061288.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fortson, Benjamin W. (2004). Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 1405103167.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gjonaij, Pashko (2001). The Ancient Illyrians.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Grimal, Pierre; Maxwell-Hyslop, A. R. (1996). The Dictionary of Classical Mythology. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 0631201025.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gruen, Erich S. (1986). The Hellenistic World and the Coming of Rome, Volume 1. University of California Press. ISBN 0520057376.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Harding, Phillip (1985). From the End of the Peloponnesian War to the Battle of Ipsus. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521299497.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hingley, Richard (2005). Globalizing Roman Culture: Unity, Diversity and Empire. Routledge. ISBN 0415351766.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hornblower, Simón; Spawforth, Antony (2003). The Oxford Classical Dictionary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198606419.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Juvenal, Decimus Junius (2009). The Satires of Decimus Junius Juvenalis, and of Aulus Persius Flaccus. BiblioBazaar, LLC. ISBN 1113525819.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kazhdan, Aleksandr Petrovich (1991). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195046528.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kipfer, Barbara Ann (2000). Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology. Springer. ISBN 0306461587.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kohl, Philip L.; Fawcett, Clare (1995). Nationalism, Politics and the Practice of Archaeology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521480655.

- Korkuti, Myzafer (2003). Parailirët, Ilirët dhe Arbërit – Histori e shkurtër. Tirana: Toena. ISBN 9992716894.

- Kühn, Herbert (1976). Geschichte der Vorgeschichtsforschung. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 3110059185.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mallory, J. P.; Adams, Douglas Q. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 1884964982.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mazaris, Maximus (1975). Mazaris' Journey to Hades or Interviews with Dead Men about Certain Officials of the Imperial Court (Seminar Classics 609). Buffalo, New York: Department of Classics, State University of New York at Buffalo.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mócsy, András (1974). Pannonia and Upper Moesia: A History of the Middle Danube Provinces of the Roman Empire. Routledge. ISBN 0710077149.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pomeroy, Sarah B.; Burstein, Stanley M.; Donlan, Walter; Roberts, Jennifer Tolbert (2008). A Brief History of Ancient Greece: Politics, Society, and Culture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195372352.

- Smith, William (1874). A Smaller Classical Dictionary of Biography, Mythology, and Geography: Abridged from the Larger Dictionary. J. Murray.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Srejovic, Dragoslav (1997). Les Illyriens et Thraces.

- Stipčević, Alexander (1989). Iliri (Second Edition). Zagreb.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Strauss, Barry (2009). The Spartacus War. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 1416532056.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Vickers, Miranda (1999). The Albanians. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1860645410.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - West, Martin Litchfield (1992). Ancient Greek Music. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198149751.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Whitehorne, John Edwin George (1994). Cleopatras. Routledge. ISBN 0415058066.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wilkes, John J. (1995). The Illyrians. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0631198075.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)