Panama Canal

The Panama Canal is 82 kilometres (51 miles) long and cuts through the isthmus of Panama, connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Due to the "S" shape of Panama, the Atlantic lies to the west of the canal and the Pacific to the east, the reverse of the customary orientation of those oceans to land in the Americas. The canal opened on August 15, 1914.

Description

Along the the canal there are 3 sets of canal locks. They are the Gatun, Pedro Miguel and the Miraflores locks. At the Atlantic end, the massive steel gates of the triple locks at Gatún are 70 feet (21 m) high and weigh 745 tons each, but are so well-counterbalanced that a 30 kW (40 horsepower) engine suffices to open and close them. Lake Gatún, which is 26 metres above sea level, is fed largely by the Chagres River, which was dammed to make the lake. From Lake Gatún, the canal passes through the continental divide at the Gaillard Cut, and then descends to the Pacific first through a single set of locks at Pedro Miguel, which as the smallest of the locks can raise or lower ships 10 ft. Then it passes to Miraflores Lake at 16.5 metres above sea level, and then through a double set of locks at Miraflores. All the locks on the canal are paired so that ships may pass in both directions. The ships are hauled through the locks with small railway engines called burros (donkeys). The Pacific end of the canal is 24 cm higher than the Atlantic end and has much greater tides.

Several islands are located within the Lake Gatún portion of the Panama Canal, including Barro Colorado Island, home of the world famous Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI).

History

Prior to the Panama Canal's construction, the fastest way to travel by ship from New York to California would have been by "rounding the Horn", the long and dangerous route via Cape Horn (at the southernmost tip of South America).

The dream of a canal across the isthmus of Central America goes back centuries, and there was serious discussion of its possible construction from the 1820s onwards. The two "most favorable" routes were those across Panama (then a part of Colombia) and across Nicaragua, with a route across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in Mexico as a third option. The Nicaragua route was seriously considered and surveyed; see Nicaragua Canal. After the success of the Suez Canal in Egypt, the French were confident that they could connect another two seas with little difficulty. In May of 1879, the International Canal Congress was held in Paris. Delegates from 22 nations considered the Nicaraguan route, the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, but the majority settled on Panama.

Ferdinand de Lesseps, who was in charge of the construction of the Suez Canal in 1869, was initially called upon to build the new canal at Panama and construction began on January 1, 1880.

Panama Railroad

The Panama Railway was built across the isthmus from 1850 to 1855. The infrastructure of this functioning railroad was a key consideration in the plan to build the canal in Panama. The railroad workers were from the United States, Europe, China, and also included some African slaves. Many of these workers had come to Panama to seek their fortune, and had arrived with little or no identification. Many died with no next of kin, nor permanent address, nor even a last name accompanied them.

Cadaver trade

As disease and exhaustion took their toll on the workers, the disposal of unidentifiable bodies was a boon to those with proper connections. Medical schools and teaching hospitals needed cadavers to train budding physicians, and paid handsomely for anonymous bodies pickled in barrels shipped up from the tropics. The Panama Railroad Company itself sold the corpses abroad, and the income generated was sufficient to maintain the Company's own hospital. A journalist reported sighting the chief doctor at the Panama Railroad Company's hospital conscientiously bleaching skeletons of dead workers, in hopes of compiling a skeletal museum of all the known races working on the railroad.

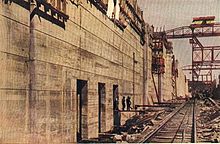

Construction

However, there was a vast difference between digging quantities of sand in a dry flat area for the Suez Canal, and removing enormous quantities of rock from the middle of a jungle. Floods, mudslides, and high mortality rates from malaria, yellow fever and other tropical diseases eventually forced the French to abandon the project (see Panama scandals).

President Theodore Roosevelt of the United States was confident that the United States could complete the project, and recognized that US control of the passage from the Atlantic to Pacific oceans would be militarily and economically important. Panama was then part of Colombia, so Roosevelt opened negotiations with the Colombians to obtain the necessary permission. In early 1903 the Hay-Herran Treaty was signed by both nations, but the Colombian Senate failed to ratify the treaty. In a controversial move, Roosevelt implied to Panamanian rebels that if they revolted, the U.S. Navy would assist their cause for independence. Panama proceeded to proclaim its independence on November 3, 1903, and the USS Nashville in local waters impeded any interference from Colombia (see gunboat diplomacy).

When fighting began Roosevelt ordered US battleships stationed off of Panama's coast for "training exercises". Many argue that fear of a war with the United States caused the Colombians to avoid any serious opposition to the revolution. The victorious Panamanians returned the favor to Roosevelt by allowing the United States control of the Panama Canal Zone on February 23, 1904 for US$10 million (as provided in the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty, signed on November 18, 1903).

Control of the zone was exercised by the Isthmian Canal Commission during canal construction. The commission was staffed by military officers and initially chaired by Admiral John C. White. The first success of the North Americans was to eliminate the noxious yellow fever that had killed so many construction workers. Based on the work of Cuban doctor Juan Carlos Finlay, Walter Reed had determined in Cuba during the Spanish-American War that the disease was spread by mosquitos. 20,000 French workers had died from it. However, new health measures led by Dr William C. Gorgas eliminated yellow fever in 1905 and improved general sanitation and working conditions.

The first chief engineer of the project was John Findlay Wallace. Hampered by disease and poor organization, his work did not go well and he resigned after one year. The second chief engineer, John Stevens, set up much of the infrastructure necessary for construction of the canal, including building housing for construction workers, rebuilding the Panama Railway to accommodate heavy freight traffic, and devising an efficient system for removing spoil from the excavations by rail. He resigned in 1907. US Colonel George Washington Goethals was the last chief engineer and his management of the project was highly praised. The work was still grueling, but great progress was made. Around this time landslides became a larger issue, especially around the Culebra Cut, where rapid oxidation of iron in the underlying strata caused loss of support. The first major slide occurred in 1907 at Cucaracha. The initial crack was first noted on October 4th, 1907, then without warning approximately 382,000 cubic metres of clay, moved more than 4 metres in 24 hours. The clay was too soft to be excavated and removed by the steam shovels and could only be removed by sluicing with water from a high level.

Ferdinand de Lesseps, had insisted on a sea-level canal, but the French engineers never found a solution for dealing with Chagres River, which crossed the line of the canal many times. The Chagres was prone to tremendous floods in the rainy season and a sea-level canal would have had to carry its entire drainage. The lock canal plan finally selected by Stevens and built by Goethals harnessed the Chagres by means of a huge earthfill dam at Gatún. The resulting artificial lake not only provided the water and hydroelectric power to operate the canal locks, but also a water "bridge" covering a third of the distance across the isthmus. Under Goethals's leadership, the engineering work on the canal was broken down into construction of the breakwaters, dams, and locks at either end; and the great task of excavation through the Continental Divide at Culebra, now known as the Gaillard Cut. Even with the change from a sea-level to lock canal, the final volume of excavation was almost four times that initially estimated by de Lesseps.

US President Woodrow Wilson triggered the blowing up of the Gamboa Dike on October 10, 1913 thus completing the construction of the canal. Numerous West Indian laborers had worked on the Canal, and official mortality figures were 5,609 lives.

According to The Panama Canal by Frederic J. Haskin, France paid $300,000,000 in an aborted attempt to build the Panama canal; later the U.S. paid $375,000,000 to complete it. 232,000,000 cubic yards (177,000,000 m³) of dirt were removed, 4,500,000 cubic yards (3,400,000 m³) of concrete were poured. At the height of construction, there were 40,000 workers working on it. All workers were paid in gold and silver coins, never in paper money.

Post-construction

When the canal opened on August 15, 1914 it was a technological marvel. A complex series of locks allowed even the largest ships to pass. The canal was an important strategic and economic asset to the US, and revolutionized world shipping patterns.

The United States used the canal during World War II to help revitalize their devastated Pacific Fleet. Some of the largest ships the United States had to send through the canal were aircraft carriers, in particular the Essex class. These were so large that, although the locks could hold them, the lampposts that lined the canal had to be removed. The largest ships able to go through the canal are described as being of Panamax size.

Return to The Panamanians

The canal and the Canal Zone surrounding it were administered by the United States until 1999 when control was relinquished to Panama. This was the result of the September 7, 1977 signing of the Torrijos - Carter Treaty in which US president Jimmy Carter conceded to Panamanian demands for control. The treaty called for a gradual handover that placed the canal completely under Panamanian jurisdiction by December 31, 1999. The treaty was highly controversial in the U.S., and its passage was by no means certain. It was revealed in 1997 by General Manuel Noriega that the Torrijos government had a plan in effect to sabotage the canal if the U.S. failed to ratify the treaty. Noriega also claims that the invasion of Panama under Operation Just Cause was primarily launched to circumvent the treaty. The controversy was largely caused becasue of U.S. suspicion that Panama would give too much power to Chinese conglomerates through alleged links between Hutchison Whampoa, and Beijing based bussiness. [1]. Some Americans were also wary of placing an extremely valuable waterway under the protection of the Panamanian security force, whose competency is questioned, see: [2]

Panama's Law No. 5 was passed on January 16, 1997 to confirm 25-to-50-year leases for the U.S.-built ports of Cristobal on the Atlantic end of the canal and Balboa on the Pacific end and "operation of the canal" to a Chinese Hong Kong corporation named Hutchison Whampoa operating under the name Hutchison Port Holdings and headed by Li Ka Shing, the wealthiest Chinese individual. Accusations that "Red China controls the Panama Canal" are based on this. [3] [4] [5]

Panama was very eager to get complete control over the canal mainly to use excess energy produced by the canal dam for profit making upon distribution, which was previously prohibited by the U.S. government. The canal system produces more than 500 gigawatts of electricity per year in hydro-electric power, but only consumes 25 percent of it in running the canal [6].

The Dam at Gatun

An enormous amount of excess soil was produced during the construction of the Panama canal. Initially, the soil was hauled to a nearby valley, then dumped and allowed to build up. This caused many problems during the rainy season and was the cause of many landslides. Later it was decided to re-use the soil, and it was used for the creation of the Chagres Dam, which held back the Chagres River to create the Gatun Lake. The dam is 1.5 miles long and slightly under 0.5 mile wide at its base. The construction of the dam involved building 2 walls along its length, using excavated rock, primarily from the Culebra cut. The space between the walls was then built up with clay. When the clay dried it adopted concrete qualities. This dam contains 16.9 million cubic metres of rock and clay which is equivalent to about one tenth of the entire excavation of the canal.

Problems

When the Canal was built in 1914, it was designed to be large enough to accommodate any vessels in the world. Technologies have advanced rapidly since then, and many vessels today are too large to fit in the canal. Presently “40 percent of the vessels going through the canal are Panamax-sized” and “approximately 60% of ships on order for construction in 1999 were post-Panamax and 30% of the global fleet is projected to be post-Panamax size by 2020” . With older vessels being replaced by these post-Panamax ships, it is expected that no more ships will be able to pass in the future. If no action is taken, the Panama Canal can become obsolete.

The second problem faced by the Canal is congestion. In 2003, 11725 vessels (32.1 vessels/day) passed through the canal and it is expected that the canal will soon approach its capacity. The Panama Canal authority has stated that “the canal is currently operating at about 93 percent of capacity. It is expected that the canal will soon reach maximum capacity and this will impose a constraint for the growth in the future.

The problems of limited capacity and inability to accommodate large vessels have given opportunities for competitors to take market share away from the canal. One competitor, Canal Interoceano de Nicaragua S.A (CIN), has already proposed to build a land bridge across Nicaragua. According to a major executive in CIN, the “target cargo would be that which is carried on post-Panamax container vessels. These vessels are too large to transit the Panama Canal, so their containers are typically off-loaded on the U.S. West Coast and moved by rail to the East Coast.” Talks have also begun to build a new canal that will be capable of accommodating large vessels. Three routes are now considered and they are through Mexico, Columbia and Nicaragua. “The Columbian and Mexican routes would allow for the construction of a sea level canal, whereas the Nicaraguan route would require a lock system.” To make matter worse, tolls are growing at an alarming rate. The cost is per TEU is $42 in 2005 and will increase to $49 in 2006 and $54 in 2007. Critics have voiced their concerns over the dramatic increase in tolls and have suggested that the Canal Authority is killing its golden goose. The tolls have increased so much that “is beginning to make the Suez Canal a viable alternative for cargoes from Asia to the U.S. East Coast.” Some liners operators have already began to react to the tolls increase by planning alternatives routes between the USA and Asia. According to these liner operators, the Suez Canal not only “offers carriers economies of scale since it is able to handle larger vessels than the Panama Canal but also Suez has good access to cargo from India and southern China, for which there is higher U.S. demand these days.”

Decreasing water level of Gatun Lake

Also a large problem is decreasing average amount of water in the Gatun Lake due largely to deforestation. The Panama Canal is dependent almost entirely on the man-made Gatun Lake for the massive amount of water used to run it. 52 million gallons of fresh water are used every time a ship traverses the canal to elevate the ship over the Miraflores, Pedro Miguel and Gatun Locks. Without the rainforest vegetation absorbing rain water and distributing it slowly and consistently into the Gatun Lake, rain flows quickly down the deforested slopes into the lake. Because of this every time a large rainfall occurs (the area receives about 10 ft. of water per year, but mostly in short intense downpours) all the water enters the Gatun in a very small period of time. When this happens the water from the Gatun Lake will be spilled out into the ocean, and in the times without heavy rainfall there will be little to no water flowing to the lake to replenish it. Deforestation also causes silt to be more easily eroded from the rootless and supportless area around the Gatun Lake and collect at its bottom, reducing its capacity.

External links

- Official website of the Panama Canal Authority

- Panama Canal Webcams

- Dr. Alonso Roy's short essays on Panama Canal History (Spanish)

- JUDICIAL WATCH, INC. v. PANAMA CANAL COMMISSION case

- Structurae: Panama Canal

- Satellite view in Google Maps

- Map of Panama Canal

- [7]

References

- LaFeber, Walter. The Panama Canal: The Crisis in Historical Perspective. Oxford, 1990. Survey of U.S. diplomatic, legal, political, economic, and military involvement with the canal.

- Major, John. Prize Possession: The United States and the Panama Canal, 1903-1979. Cambridge University Press, 1993. A comprehensive history of U.S. policy, from Teddy Roosevelt to Jimmy Carter.

- McCullough, David. The Path Between the Seas: The Creation of the Panama Canal, 1870-1914. Simon & Schuster, 1978. Comprehensive history of the building of the canal.

- Gold, Susan Dudley. The Panama Canal Transfer: Controversy at the Crossroads. Raintree Steck-Vaughn, 1999. An introduction to the canal's development and ultimate surrender to Panamanian control in 1999. For middle-school readers.