Population

A population is all the organisms of the same group or species who live in the same geographical area and are capable of interbreeding.[1][2] In ecology the population of a certain species in a certain area is estimated using the Lincoln Index. The area that is used to define a sexual population is such that inter-breeding is possible between any pair within the area and more probable than cross-breeding with individuals from other areas. Normally breeding is substantially more common within the area than across the border.[3]

In sociology, population refers to a collection of human beings. Demography is a social science which entails the statistical study of human populations. This article refers mainly to human population.

==Population genetics== STEVE WAS HERE In population genetics a sexual population is a set of organisms in which any pair of members can breed together. This means that they can regularly exchange gametes to produce normally-fertile offspring, and such a breeding group is also known therefore as a gamodeme. This also implies that all members belong to the same of species, such as humans.[4] .If the gamodeme is very large (theoretically, approaching infinity), and all gene alleles are uniformly distributed by the gametes within it, the gamodeme is said to be panmictic. Under this state, allele (gamete) frequencies can be converted to genotype (zygote) frequencies by expanding an appropriate quadratic equation, as shown by Sir Ronald Fisher in his establishment of quantitative genetics.[5] Unfortunately, this seldom occurs in nature : localisation of gamete exchange - through dispersal limitations, or preferential mating, or cataclysm, or other cause - may lead to small actual gamodemes which exchange gametes reasonably uniformly within themselves, but are virtually separated from their neighbouring gamodemes. However, there may be low frequencies of exchange with these neighbours. This may be viewed as the breaking up of a large sexual population(panmictic)into smaller overlapping sexual populations. This failure of panmixia leads to two important changes in overall population structure: (1).the component gamodemes vary (through gamete sampling) in their allele frequencies when compared with each other and with the theoretical panmictic original (this is known as dispersion, and its details can be estimated using expansion of an appropriate binomial equation); and (2). the level of homozygosity rises in the entire collection of gamodemes. The overall rise in homozygosity is quantified by the inbreeding coefficient (f or φ). Note that all homozygotes are increased in frequency - both the deleterious and the desirable! The mean phenotype of the gamodemes collection is lower than that of the panmictic "original" - which is known as inbreeding depression. It is most important to note, however, that some dispersion lines will be superior to the panmictic original, while some will be about the same, and some will be inferior. The probabilities of each can be estimated from those binomial equations. In plant and animal breeding, procedures have been developed which deliberately utilise the effects of dispersion (such as line breeding, pure-line breeding, back-crossing). It can be shown that dispersion-assisted selection leads to the greatest genetic advance (ΔG = change in the phenotypic mean), and is much more powerful than selection acting without attendant dispersion. This is so for both allogamous (random fertilization)[6] and autogamous (self-fertilization) gamodemes[7]

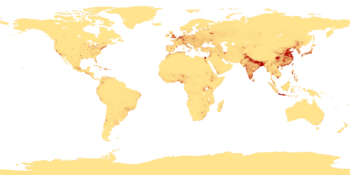

World human population

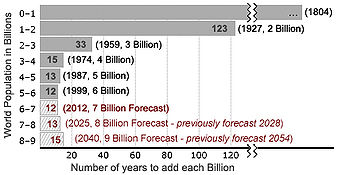

As of today's date, the world population is estimated by the United States Census Bureau to be 8.106 billion.[8] The US Census Bureau estimates the 7 billion number was surpassed on 12 March 2012. According to a separate estimate by the United Nations, Earth’s population exceeded 7 billion in October 2011, a milestone that offers unprecedented challenges and opportunities to all of humanity, according to UNFPA, the United Nations Population Fund.[9]

According to papers published by the United States Census Bureau, the world population hit 6.5 billion (6,500,000,000) on 24 February 2006. The United Nations Population Fund designated 12 October 1999 as the approximate day on which world population reached 6 billion. This was about 12 years after world population reached 5 billion in 1987, and 6 years after world population reached 5.5 billion in 1993. The population of some[which?] countries, such as Nigeria, is not even known to the nearest million,[10] so there is a considerable margin of error in such estimates.[11]

Researcher, Carl Haub, calculated that a total of over 100 billion people have probably been born in the last 2000 years.[12]

Predicted growth and decline

Population growth increased significantly as the Industrial Revolution gathered pace from 1700 onwards.[13] The last 50 years have seen a yet more rapid increase in the rate of population growth[13] due to medical advances and substantial increases in agricultural productivity, particularly beginning in the 1960s,[14] made by the Green Revolution.[15] In 2007 the United Nations Population Division projected that the world's population will likely surpass 10 billion in 2055.[16]

In the future, world population has been expected to reach a peak of growth, there it will decline due to economic reasons, health concerns, land exhaustion and environmental hazards. According to one report, it is very likely that the world's population will stop growing before the end of the 21st century. Further, there is some likelihood that population will actually decline before 2100.[17] Population has already declined in the last decade or two in Eastern Europe, the Baltics and in the Commonwealth of Independent States.[18]

The population pattern of less-developed regions of the world in recent years has been marked by gradually declining birth rates following an earlier sharp reduction in death rates.[19] This transition from high birth and death rates to low birth and death rates is often referred to as the demographic transition.[19]

Control

Human population control is the practice of artificially altering the rate of growth of a human population. Historically, human population control has been implemented by limiting the population's birth rate, usually by government mandate, and has been undertaken as a response to factors including high or increasing levels of poverty, environmental concerns, religious reasons, and overpopulation. While population control can involve measures that improve people's lives by giving them greater control of their reproduction, some programs have exposed them to exploitation.

Worldwide, the population control movement was active throughout the 1960s and 1970s, driving many reproductive health and family planning programs. In the 1980s, tension grew between population control advocates and women's health activists who advanced women's reproductive rights as part of a human rights-based approach.[20] Growing opposition to the narrow population control focus led to a significant change in population control policies in the early 1990s.[21]

See also

Notes

- ^ "Population". Biology Online. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ^ "Definition of population (biology)". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

a community of animals, plants, or humans among whose members interbreeding occurs

- ^ Hartl, Daniel (2007). Principles of Population Genetics. Sinauer Associates. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-87893-308-2.

- ^ Hartl, Daniel (2007). Principles of Population Genetics. Sinauer Associates. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-87893-308-2.

- ^ Fisher, R. A. (1999). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-850440-3.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Text "title - The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection" ignored (help) - ^ Gordon, Ian L. (2000). "Quantitative genetics of allogamous F2 : an origin of randomly fertilized populations". Heredity. 85: 43–52.

- ^ Gordon, Ian L. (2001). "Quantitative genetics of autogamous F2". Hereditas. 134: 255–262.

- ^ U.S. Census Bureau - World POPClock Projection

- ^ to a World of Seven Billion PeopleUNFPA 12.9.2011

- ^ "Cities in Nigeria: 2005 Population Estimates — MongaBay.com". Retrieved 1 July 2008.

- ^ "Country Profile: Nigeria". BBC News. 24 December 2009. Retrieved 1 July 2008.

- ^ Haub, C. 1995/2004. “How Many People Have Ever Lived On Earth?” Population Today, http://www.prb.org/Articles/2002/HowManyPeopleHaveEverLivedonEarth.aspx

- ^ a b As graphically illustrated by population since 10,000BC and population since 1000AD

- ^ "The end of India's green revolution?". BBC News. 29 May 2006. Retrieved 29 November 2009.

- ^ Food First/Institute for Food and Development Policy

- ^ "World population will increase by 2.5 billion by 2050; people over 60 to increase by more than 1 billion" (Press release). United Nations Population Division. 13 March 2007. Retrieved 14 March 2007.

The world population continues its path towards population ageing and is on track to surpass 9 billion persons by 2050.

- ^ "The End of World Population Growth". Retrieved 4 November 2008.

- ^ Shackman, Gene, Xun Wang and Ya-Lin Liu. 2011. Brief review of world population trends. Available at http://gsociology.icaap.org/report/demsum.html

- ^ a b http://users.rcn.com/jkimball.ma.ultranet/BiologyPages/P/Populations.html

- ^ Knudsen, Lara (2006). Reproductive Rights in a Global Context. Vanderbilt University Press. p. 2. ISBN 0-8265-1528-2, 9780826515285.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Knudsen, Lara (2006). Reproductive Rights in a Global Context. Vanderbilt University Press. pp. 4–5. ISBN 0-8265-1528-2, 9780826515285.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

External links

- UNFPA, The United Nations Population Fund

- United Nations Population Division

- CICRED homepage a platform for interaction between research centres and international organizations, such as the United Nations Population Division, UNFPA, WHO and FAO.

- Current World Population

- NECSP HomePage

- Overpopulation

- Population Matters

- Population Reference Bureau (2005). Retrieved 13 February 2005.

- Population World: Population of World. Retrieved 13 February 2004.

- SIEDS, Italian Society of Economics Demography and Statistics

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe - Official Web Site

- World Population Counter, and separate regions.

- WorldPopClock.com. (French)

- Populations du monde. (French)

- OECD population data

- Understanding the World Today Reports about world and regional population trends