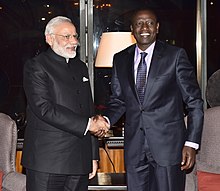

William Ruto

This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (May 2022) |

William Ruto | |

|---|---|

| |

| President-elect of Kenya | |

| Assuming office TBD | |

| Deputy | Rigathi Gachagua (elect) |

| Succeeding | Uhuru Kenyatta |

| Deputy President of Kenya | |

| Assumed office 9 April 2013 | |

| President | Uhuru Kenyatta |

| Preceded by | Kalonzo Musyoka (Vice President) |

| Succeeded by | Rigathi Gachagua (elect) |

| Minister for Higher Education | |

| In office 21 April 2010 – 19 October 2010 | |

| President | Mwai Kibaki |

| Prime Minister | Raila Odinga |

| Succeeded by | Hellen Jepkemoi Sambili (acting) |

| Minister of Agriculture | |

| In office 17 April 2008 – 21 April 2010 | |

| President | Mwai Kibaki |

| Prime Minister | Raila Odinga |

| Preceded by | Kipruto Rono Arap Kirwa |

| Succeeded by | Sally Kosgei |

| Minister of Home Affairs | |

| In office 30 August 2002 – December 2002 | |

| President | Daniel Toroitich arap Moi |

| Preceded by | George Saitoti |

| Succeeded by | Moody Awori |

| Member of Parliament for Eldoret North | |

| In office 1998–2013 | |

| Preceded by | Reuben Chesire |

| Succeeded by | Constituency abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | William Kipchirchir Samoei Arap Ruto 21 December 1966 Kamagut, Kenya |

| Political party |

|

| Spouse | |

| Children | 7 |

| Education | University of Nairobi (BSc, MSc, PhD) |

| Website | Official website |

William Samoei Arap Ruto (born 21 December 1966) is a Kenyan politician, deputy president, and since August 2022 president-elect of Kenya.[1]

Before his elevation to become the nation's next head of state in the 2022 presidential election, Ruto served since 2013 as deputy president[2][3][4] having been elected in the 2013 election on the Jubilee Alliance ticket to serve under President Uhuru Kenyatta.

Ruto was a Member of Parliament (MP) from 1998 to 2013 and served as Minister for Home Affairs in the Daniel Arap Moi administration from August to December 2002. He later served in the Mwai Kibaki administration as Minister of Agriculture from 2008 to 2010 and as Minister for Higher Education from April to October 2010.

Early life and education

A member of the Kalenjin people in the Rift Valley Province,[5] William Ruto was born on 21 December 1966 in Sambut village, Kamagut, Uasin Gishu County, to Daniel Cheruiyot and Sarah Cheruiyot.[6] He attended Kerotet Primary School for his primary school education. He was enrolled in Wareng Secondary School for his Ordinary Levels education before proceeding to Kapsabet Boys High School in Nandi County for his Advanced Levels. He then went on to receive a BSc in Botany and Zoology from the University of Nairobi, graduating in 1990. Ruto later enrolled for a MSc in Plant ecology, graduating in 2011. The following year, he enrolled for a Ph.D. and after several setbacks,[7] he completed and was awarded a Ph.D. from the University of Nairobi, graduating on 21 December 2018. Ruto authored several papers including a paper titled Plant Species Diversity and Composition of Two Wetlands in the Nairobi National Park, Kenya.[8] During his time in the campus for the undergraduate course, Ruto was an active member of the Christian Union. He also served as the Chairman of the University of Nairobi's choir.[9]

It is through his church leadership activities at the University of Nairobi that Ruto met President Daniel Arap Moi, who would later introduce him to politics during the 1992 general elections.[10]

Ruto owns a considerable chicken farm in his home village of Sugoi, which was originally inspired by his stint as a live chicken hawker on the Nairobi-Eldoret highway. [11]

Political career

After graduating from the University of Nairobi in 1990, Ruto was employed as a teacher in the North Rift region of Kenya from 1990 to 1992, where he was also the leader of the local African Inland Church (AIC) Choir.[10]

YK'92

Ruto began his political career when he became the treasurer of the YK'92 campaign group that was lobbying for the re-election of President Moi in 1992, from which he learned the basics of Kenyan politics.[9][12] He is also believed to have accumulated some wealth in this period.[13] After the 1992 elections, President Moi disbanded YK'92 and Ruto attempted to vie for various KANU (then Kenya's ruling party) branch party positions but did not succeed.[14]

Member of Parliament

Ruto ran for a parliamentary seat in the 1997 general election. He surprisingly beat the incumbent, Reuben Chesire, Moi's preferred candidate, as well as the Uasin Gishu KANU branch chairman and assistant minister.[15][16] After this, he would later gain favour with Moi and be appointed KANU Director of Elections.[17] His strong support in 2002 for Moi's preferred successor Uhuru Kenyatta saw him get a place as assistant minister in the Home Affairs (Interior) ministry docket. Later in that election, as some government ministers resigned to join the opposition, he would be promoted to be the full Cabinet Minister in the ministry.[13] KANU lost the election but he retained his parliamentary seat. Ruto would thereafter be elected KANU Secretary General in 2005 with Uhuru Kenyatta getting elected as Chairman.[17]

In 2005, Kenya held a constitutional referendum which KANU opposed.[9] Some members of the ruling NARC coalition government, mainly former KANU ministers who had joined the opposition coalition in 2002 under the LDP banner and who were disgruntled as the President Kibaki had not honored a pre-election MoU[18] on power-sharing and creation of a Prime Minister post, joined KANU to oppose the proposed constitution.[19] Since the symbol of the "No" vote was an Orange, this new grouping named their movement the Orange Democratic Movement (ODM). Ruto was part of its top brass, dubbed the Pentagon. He solidified his voter base in the Rift Valley Province. ODM was victorious in the referendum.[20]

In January 2006, Ruto declared publicly that he would vie for the presidency in the next general election (2007). His statement was condemned by some of his KANU colleagues, including former president Moi. By this time, ODM had morphed into a political party.[9] Ruto sought the nomination of the Orange Democratic Movement (ODM) as its presidential candidate, but on 1 September 2007, he placed third with 368 votes. The winner was Raila Odinga with 2,656 votes and the runner-up was Musalia Mudavadi with 391.[21] Ruto expressed his support for Odinga after the vote.[22] As KANU under Uhuru Kenyatta moved to support Kibaki,[23] he resigned from his post as KANU secretary general on 6 October 2007.[24]

The presidential election of December 2007 ended in an impasse. Kenya's electoral commission declared Kibaki the winner, but Raila and ODM claimed the victory. Mwai Kibaki was hurriedly sworn in as the president of the December 2007 presidential election. Following the election and the dispute over the result, Kenya was engulfed by a violent political crisis. Kibaki and Odinga agreed to form a power-sharing government.[25][26] In the grand coalition Cabinet named on 13 April 2008[26] and sworn in on 17 April,[25] Ruto was appointed as Minister for Agriculture.[26] Ruto also became the Eldoret North's Member of Parliament from 2008 to 4 March 2013.[27]

Ruto was among the list of people who were indicted to stand trial at the ICC for their involvement in Kenya's 2007/2008 political violence. However, the ICC case was faced with challenges, especially concerning the withdrawal of key prosecution witnesses. In April 2016, the Court dropped charges against Ruto.[28]

On 21 April 2010, Ruto was transferred from the Agriculture Ministry and posted to the Higher Education Ministry, swapping posts with Sally Kosgei.[29] On 24 August 2011, Ruto was relieved of his ministerial duties and remained a member of parliament. He joined with Uhuru Kenyatta to form the Jubilee alliance for the 2013 presidential election.

Acting President

He served as the Acting President of Kenya between 5 and 8 October 2014 while President Uhuru Kenyatta was away at the Hague.

Deputy President

On 6 October 2014, Ruto was appointed acting president of Kenya by President Uhuru Kenyatta following his summons to appear before the ICC.[30]

In the August 2017 General Elections, Uhuru and Ruto were declared victors after garnering 54% of the total votes cast. However, the Supreme Court of Kenya nullified the election, and a fresh election was held in October 2017. The opposition boycotted the fresh election and Uhuru and Ruto were re-elected with 98% of the total votes cast. The Supreme Court upheld the results of this second election.[31]

Presidential candidate

On December 2020 Ruto announced his alliance with the newly formed United Democratic Alliance party.[32][33] He was the only presidential candidate to attend the second part of the 2022 presidential debate.[34]

Controversies

Land grabbing

Ruto has been involved in many reported land grabbing controversies, including several Kenyan state corporations embroiled in endless litigation over the land grabs.[35] Much media, and many politicians and activists often describe him as "Arap-Mashamba" (the word being a portmanteau of son of lands).[36][37][38]

Weston hotel land

Ruto has been involved in a land grabbing saga involving his mysterious acquisition of Weston hotel land, pitted against public counter-accusations with several state corporations in Kenya, all surrounding the original owner of the land. According to The Standard, the Kenya Civil Aviation Authority (KCAA), a state agency, was duped into surrendering the land on which the Weston hotel was built.[35][39] In 2001, KCAA, which originally occupied the land, was given alternative pieces of land belonging to another state agency, the meteorological department.[39] KCAA did not occupy the alternative piece of land upon which Ruto's Weston hotel was built. According to KCAA, a powerful cartel, working in the lands ministry was involved in a conspiracy to relinquish the same piece of land with several land ministry officers also involved in the conspiracy.[39] In January 2019, it emerged that according to another state agency, the National Lands Commission, Ruto owed and needed to pay the people of Kenya for the land 0.773 acres opposite Wilson Airport upon which the Weston hotel was built. In February 2019, Ruto publicly admitted the Weston land had been acquired illegally by the original owners who sold him the land, and that he had no knowledge of matter.[40][41][42] In August 2020, Ruto offered to pay the state agency for the land.[43] Later in 2020, KCAA was refused to be compensated for the land and so, demanded demolition of the hotel because of acquisition through illegality, fraud and corruption. According to the KCAA, the public land was designated for the construction of headquarters and flight paths, and it had been disposed of the land by collusion with private entities, Priority ltd and Monene Investments both reported to be associated with Ruto.[44][45][46] Later in the same month, another legislator, Ngunjiri Wambugu, demanded all other cases in Kenya involving stolen property be thrown out as long as suspects were willing to compensate for it, in an effort to complain about the preferential treatment Ruto was receiving for his involvement in the state's stolen property. In December 2020, the KCB Bank backed Ruto in the court battle to repossess the land, fearing the loss of security against the advancement of 1.2 billion shillings in Weston hotel associated with Ruto.[47]

KPC Ngong forest land scandal

In 2004, Ruto was charged with defrauding another state corporation Kenya Pipeline Company (KPC) of huge amounts of money through dubious land deals.[35] He was acquitted in 2011 but in 2020, as his relationship with President Uhuru Kenyatta seemed to falter amid the President's push for an anti-corruption war,[48] the police re-opened investigations in the case.[49]

Muteshi Land

In June 2013, Ruto was ordered by a court to pay a victim of 2007/08 post-election violence 5 million shillings for illegally taking away his land during the post-election violence.[50][35] In the same judgement, Ruto was evicted from the grabbed land in Uasin Gishu. Adrian Muteshi had accused Ruto of grabbing[35] and trespassing on his 100-acre piece of land in Uasin Gishu after he, Adrian, had fled his land for safety during the post-election violence of 2007/08.[50] In February 2014, Ruto appealed the court order to pay the 5 million shilling fine. In 2017, Ruto withdrew the appeal against the judgment. In October 2020, Adrian Muteshi died of an unspecified cause at the age of 86.[50]

Joseph Murumbi's 900-acres

In October 2019, the Daily Nation reported that Ruto's acquisition of a 900-acre piece of land of another former vice president Joseph Murumbi haunted Ruto because he had been involved in the irregular acquisition of the land.[51] In the same month, Ruto claimed that the articles were persistent, and obviously sponsored fake news. Later, still in the same month, a human rights lobby activist, Trusted Society of Human Rights Alliance called for an investigation into the mysterious acquisition of a 900-acre piece of land that formerly belonged to another former vice-president Murumbi.[52] According to the allegations, Murumbi had been involved in a loan dispute over loan defaults with a state corporation, AFC, against the land that was charged as a security for the loan.[52] It is alleged that Murumbi defaulted the loan and AFC took over ownership of the land that was eventually sold to Ruto after he paid off the loan owed to the state corporation.[52]

Jacob Juma assassination allegations

Ruto has been widely and repeatedly linked to the assassination of Jacob Juma by several media, activists, politicians, opposition figures in Kenya, including Jacob Juma himself.[53][54] Jacob Juma was a wealthy businessman[55] who became a fierce government critic and anti-corruption crusader who became known for posting targeted cryptic tweets against Ruto and the Jubilee government months before he was assassinated in Nairobi.[56][57][58] In December 2015, Jacob Juma, in his tweets, claimed Ruto was obsessed with killing him.[54][59] In May 2016, Jacob Juma was shot dead along Ngong Road.[60] In the same month, during the burial of Jacob Juma, a former Lugari MP Cyrus Jirongo and previously a close ally of Ruto claimed Jacob Juma had physically assaulted Ruto by slapping him for having a sour relationship over unspecified reasons.[61] Jirongo urged police to investigate the assassination based on the assault.[62] Later in the month, Ruto threatened to sue Jirongo for linking him to the assassination.[63][64] Jirongo claimed that he and another former minister, Chris Okemo, were personally involved in paying the murdered government critic university's tuition fees, and that he knew the matter surrounding the controversy all too well.[61] According to Jirongo, the same assassins were involved in the murder of Meshack Yebei, another murdered prospective defence witness in the ICC trial against Ruto.[61]

In June 2016, the Canadian newspaper Financial Post and the Kenyan newspaper The Standard both reported that Jacob Juma was the director of a Canadian company (Pacific Wildcat) whose license to explore $2 billion worth of minerals in Kwale county in Kenya was cancelled just after the Jubilee government took over.[65][66] This cancellation led Jacob Juma to call a press conference where he claimed that the then Mining Minister Najib Balala was demanding a bribe to have the cancelled license re-issued to the company. This cancellation led Jacob Juma into personal financial ruin, and it was reported he was routinely borrowing money. He became a fierce government critic after he felt short-changed out of the mining license that eventually caused his company to lose money.[67] According to a different company official of the same Canadian company, Ruto and Balala demanded transfer of the mining company's license to a new company with the Kenyan government to receive a 50% stake in the new company for free.[65][66] This eventually led Jacob Juma to become fiercely critical of Ruto and the Jubilee government in tweets, media interviews, court filings, and political correspondence with opposition figures as well as diplomatic missions in Kenya.[57][68] It later emerged Jacob Juma had promised the board of the Canadian company Pacific Wildcat that he would fight bureaucratic delays as well as the corruption that would stand in the way of getting the mining license. A high court ruling in Kenya found that the Mining minister was right to cancel the license of the Canadian company.[69]

In October 2016, photojournalist Boniface Mwangi also linked Ruto to the assassination.[70][71] Ruto sued him for defamation. According to Ruto's lawyer, the claims by the activist had lowered Ruto's standing among Kenya's "high thinking" people.[71]

In December 2016, one of the personnel from Ruto's office was reported to also link Ruto to the assassination by delivering a letter to Mwangi to help with his defamation case against Ruto by providing details of the murder by persons in Ruto's office.[72][73] In the same month, it was reported that the personnel was to be charged in court for extortion.[73] An investigating officer claimed that the arrested personnel from Ruto's office claimed that another personnel in Ruto's office called Rono had credible information that Activist Mwangi could be killed in a stage-managed road accident.[74] The arrested personnel from Ruto's office was later sent for mental check-up after he further claimed that he was coached to lie about his claims of Jacob Juma's murder by Mwangi.[74]

In February 2017, it was reported that Mwangi claimed Ruto wanted him dead like he killed Jacob Juma.[75][76]

Corruption allegations

Ruto has faced several allegations of corruption and land grabbing.[77] His former ally turned bitter nemesis Raila Odinga has accused him of corruption questioning the sources of the funds he dishes out at fundraisers on a regular basis. Several of his allies and aides have also been forced to resign amid corruption scandals.[78] He has also faced accusations of grabbing land from a primary school in Nairobi[79] and land meant for a sewerage treatment plant in Ruai, Nairobi.[80] Ruto has denied these allegations.[77]

International Criminal Court summons

In December 2010, the prosecutor of the International Criminal Court announced that he was seeking the summons of six people, including Ruto, over their involvement in the 2007–8 electoral violence.[81] The ICC's Pre-Trial Chamber subsequently issued a summons for Ruto at the prosecutor's request.[82] Ruto was accused of planning and organizing crimes against supporters of President Kibaki's Party of National Unity. He was charged with three counts of crimes against humanity, one for murder, one for the forcible transfer of population, and one for persecution. On 23 January 2012, the ICC confirmed the charges against Ruto and Joshua Sang, in a case that also involved Uhuru Kenyatta, Francis Muthaura, Henry Kosgey and Major General Mohammed Hussein Ali.[citation needed] Ruto told the US government that the Kiambaa church fire on 1 January 2008 after the 2007 general election was merely accidental.[83] The Waki Commission report stated in 2009 that "the incident which captured the attention of both Kenyans and the world was a deliberate burning of live people, mostly Kikuyu women, and children huddled together in a church" in Kiambaa on 1 January 2008.[citation needed] In April 2016, the prosecution of Ruto was abandoned by the International Criminal Court.[28]

Home attack

On 28 July 2017, Ruto's home was targeted by at least one attacker armed with a machete, and the police officer on duty guarding the residence was injured.[84] During the time of the attack, he and his family were not at the compound as he had left hours earlier for a campaign rally in Kitale. There were reports of gunfire and several security sources said the attack was staged by multiple people. Police initially thought there were a few attackers because the attacker used different firearms.[85][86] Around 48 hours later, Kenya Police chief Joseph Boinnet announced that the attacker was shot dead and the situation was under control.[87]

Personal life

Ruto married his wife Rachel Chebet in 1991. The young couple first lived in Dagoretti where they had their first child, Nick Ruto.[88]

References

- ^ "Kenya's deputy president Ruto declared election winner". AP NEWS. 15 August 2022. Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ "The Office Of The Deputy President, Kenya". deputypresident.go.ke. 17 May 2022. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ "William Ruto". kenyans.co.ke. 17 May 2022. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ "Kenya General Election Results (2013)". iebc.or.ke. 17 May 2022. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ "William Ruto's rise from chicken seller to Kenya's president-elect". BBC News. 15 August 2022. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- ^ "William Samoei Arap Ruto". Africa Confidential. Archived from the original on 30 May 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- ^ "I failed Ph.D. exam, admits DP William Ruto". Business Today. 2 December 2016. Archived from the original on 21 December 2018. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- ^ Ruto, W. K. S. (2 November 2012). "Plant Species Diversity and Composition of Two Wetlands in the Nairobi National Park, Kenya". Journal of Wetlands Ecology. 6: 7–15. doi:10.3126/jowe.v6i0.5909. Archived from the original on 21 December 2018. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- ^ a b c d Joel Muinde (21 July 2019). "A brief profile of DP William Ruto: PHOTOS". K24. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ a b Fayo, G (18 May 2022). "How shy Ruto rose from a CU leader to money, power". The Business Daily. Archived from the original on 2 June 2022. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ^ Shiundu, Alphonce. "William Ruto: How he rose from roadside Kuku-seller to multi-billionaire". Standard Entertainment and Lifestyle. Archived from the original on 26 July 2022. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ Hull, C. Bryson (11 January 2008). "Ghost of Moi surfaces in Kenya's violence". Reuters. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 16 December 2020 – via www.Reuters.com.

- ^ a b "William Ruto: Kenya's deputy president". BBC News. 9 September 2013. Archived from the original on 16 August 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ "How Moi created then decimated youth lobby | Nation". 3 July 2020. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Courting the Kalenjin: The Failure of Dynasticism and the Strength of the ODM Wave in Kenya's Rift Valley Province, Gabrielle Lynch, African Affairs, Vol. 107, No. 429 (Oct. 2008), pp. 541–568

- ^ "Mzee Moi was 'vicious', interesting fellow – DP Ruto". The Star. Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ a b Omanga, -Beauttah. "How Ruto rose to be influential personality in Kenyan politics". The Standard (Kenya). Archived from the original on 5 June 2022. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ Wanga, Justus (4 September 2021). "Matere Kerri: Why we broke the famous MoU with Raila". The Nation. Archived from the original on 18 May 2022. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ^ "Kenyans say no to new constitution". 22 November 2005. Archived from the original on 27 May 2020. Retrieved 29 April 2020 – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ Andreassen, Bård Anders; Tostensen, Arne (16 December 2006). "Of Oranges and Bananas: The 2005 Kenya Referendum on the Constitution". CMI Working Paper. WP 2006: 13. Archived from the original on 20 February 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2020 – via www.cmi.no.

- ^ "It's Raila for President", The East African Standard, 1 September 2007.[dead link]

- ^ Maina Muiruri, "ODM 'pentagon' promises to keep the team intact"[permanent dead link], The East African Standard, 2 September 2007.

- ^ "Nation – Breaking News, Kenya, Africa, Politics, Business, Sports | HOME". Nation. Archived from the original on 21 October 2017. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ The East African Standard, 7 October 2007: Ruto abandons Kanu's top post Archived 31 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Odinga sworn in as Kenya PM" Archived 26 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Al Jazeera, 17 April 2008.

- ^ a b c Anthony Kariuki, "Kibaki names Raila PM in new Cabinet"[permanent dead link], nationmedia.com, 13 April 2008.

- ^ "William Ruto, EGH, EBS". Mzalendo. Archived from the original on 6 December 2019. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- ^ a b "International criminal court abandons case against William Ruto". The Guardian. 5 April 2016. Archived from the original on 5 April 2016. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- ^ Kenya's cabinet reshuffled Archived 18 August 2022 at the Wayback Machine IOL.

- ^ "The day William Ruto was president for 48 hours". The Standard (Kenya). Archived from the original on 9 January 2022. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ "Kenya's Supreme Court upholds repeat presidential vote". CNBC. 20 November 2017. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ^ "Kenya: Has Deputy President Ruto joined the new UDA Party?". The Africa Report.com. 14 January 2021. Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ Kibor, Fred. "Rift MPs: Ruto will use UDA to contest for presidency in 2022". The Standard (Kenya). Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ Winfrey Owino; Betty Njeru. "Moderators place DP William Ruto between a rock and a hard place during debate". The Standard (Kenya). Archived from the original on 18 August 2022. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

United Democratic Alliance presidential candidate William Ruto was the only candidate who took part in the second tier of the debate, after his main rival, Raila Odinga, of the Azimio la Umoja-One Kenya coalition skipped.

- ^ a b c d e Reporter, Nation (3 June 2015). "How claims of dubious land deals are hurting DP's image". Daily Nation. Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ Mutiva, Tony (5 November 2016). "Joho nicknames Ruto 'Arap Mashamba'". hivisasa.com. Archived from the original on 18 August 2022. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ Nyamori, Moses (18 January 2021). "Kalonzo labels Ruto chief land grabber as he fights off accusation". The Standard (Kenya). Archived from the original on 22 May 2022. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ Mwangi, Anthony (19 January 2021). "You are a land grabber, furious Kalonzo tells Deputy President – People Daily". www.pd.co.ke. Archived from the original on 18 August 2022. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ a b c Ombati, Cyrus; Mosoku, Geoffrey (1 November 2018). "How state agency was duped to surrender Weston land". The Standard (Kenya). Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ Chepkwony, Julius (13 February 2019). "Storm over Ruto admission over Weston". The Standard (Kenya). Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ Okoth, Brian (12 February 2019). "DP Ruto finally admits Weston Hotel land was illegally acquired". Citizentv.co.ke. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ Vidija, Patrick (12 February 2019). "I was an innocent buyer of illegal Weston land – DP Ruto". The Star (Kenya). Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ Muthoni, Kamau (10 August 2020). "Ruto seeks to save hotel by paying for land a second time". The Standard (Kenya). Archived from the original on 25 December 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ Kiplagat, Sam (7 August 2020). "DP Ruto's hotel in fresh fight against land takeover". Nairobi News. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ Wambulwa, Annette (28 May 2020). "Weston Hotel concealed evidence in land row case – KCAA". The Star (Kenya). Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ Muthoni, Kamau (28 May 2020). "KCAA: Weston colluded with firms to grab land". The Standard (Kenya). Archived from the original on 18 December 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ December 18, 2020, Friday (18 December 2020). "KCB supports Ruto in Weston Hotel demolition row". Business Daily Africa. Archived from the original on 20 December 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Not even family or close allies will be spared in graft war, warns Uhuru". The Standard. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ Ombati, Cyrus; Obala, Roselyn. "DCI reopens Ruto land fraud case nine years after acquittal". The Standard. Archived from the original on 4 December 2020. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ a b c Ogemba, Paul (29 October 2020). "End of an era for the man who took DP Ruto head-on for grabbing his land". The Standard (Kenya). Archived from the original on 25 December 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ "Ruto sucked into controversy over purchase of 900 acres". Daily Monitor. 4 October 2019. Archived from the original on 4 May 2021. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ a b c Gachuhi, Kennedy (6 October 2019). "How taxpayers lost Sh180m in former VP Murumbi land sale". The Standard (Kenya). Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ Mathenge, Oliver (6 May 2016). "Jacob Juma made enemies online including Ruto". The Star (Kenya). Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Khalwale's Allegation: Jacob Juma said that DP Ruto is obsessed with killing him". Standard Digital, KTN News Video. 13 May 2016. Archived from the original on 9 August 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ Nsehe, Mfonobong (6 May 2016). "Kenyan Tycoon Jacob Juma Shot Dead In Nairobi". Forbes. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ Gumbihi, Hudson. "From Westlands to Ngong road: How Jacob Juma's murder was planned and executed". Standard Entertainment and Lifestyle. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ a b "8 times Jacob Juma correctly predicted the future". Nairobi News. 9 November 2016. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ Chweya, Edward (3 October 2016). "Jacob Juma's death: William Ruto and Boniface Mwangi's roles explained". Tuko.co.ke – Kenya news. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ "Jacob Juma Status". Twitter. Archived from the original on 18 August 2022. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ "Kenyan businessman Jacob Juma shot dead in Nairobi". BBC News. 6 May 2016. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ a b c Kiberenge, Kenfrey (12 May 2016). "Jirongo: Jacob Juma's Troubles Started After He Physically Assaulted DP Ruto Recently". Nairobi News. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ Mathenge, Oliver; Letoo, Stephen (13 May 2016). "DP Ruto to sue Jirongo over Jacob Juma death link". The Star. Archived from the original on 18 August 2022. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ Okoth, Brian (5 June 2016). "Ruto answers Jirongo after Jirongo linked him to Juma's death". Citizentv.co.ke. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ Ambania, Sylvania (8 June 2016). "Ruto: I'm ready to record statement on Jacob Juma's death". Nairobi News. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ a b Mwalimu, Kaka (23 June 2016). "Revealed: The genesis of Ruto-Jacob Juma fall-out". hivisasa.com. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ a b Wafula, Paul (22 June 2016). "Ruto-Jacob Juma fallout linked to Sh210b mineral find in Mrima Hills". The Standard (Kenya). Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ Gumbihi, Hudson. "Life has never been the same since Jacob Juma was murdered- wife". Standard Entertainment and Lifestyle. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ "Opposition leaders asked not to politicize the killing of businessman Jacob Juma". Nation. 9 May 2016. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ Agoya, Vincent (20 March 2015). "High Court supports Najib Balala move to cancel mining firm licence". Nation. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ Murimi, Maureen (5 October 2016). "Activist Mwangi fires at DP Ruto over 'defamatory' tweet". Citizentv.co.ke. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ a b Maina, Carol (7 October 2016). "Ruto sues Boniface Mwangi for linking him to Jacob Juma death". The Star. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ Maina, Carol (1 December 2016). "Man 'with details of Jacob Juma murder from Ruto's office' held 4 days". The Star. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ a b Makana, Fred (2 December 2016). "I work in DP Ruto's office, claims suspect in Jacob Juma murder case". The Standard (Kenya). Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ a b Kakah, Maureen; Munguti, Richard (7 December 2016). "Man sent for mental check-up after fresh claims on Jacob Juma murder". Nation. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ Lang'at, Patrick. "Boniface Mwangi now wants state security". Nairobi News. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ Tubei, George (5 February 2017). "'William Ruto wants me dead like he killed Jacob Juma' Mwangi claims". Pulse Live Kenya.

- ^ a b "Ruto denies allegations of corruption and land grabbing | Nation". 3 July 2020. Archived from the original on 19 December 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ "Deputy President big loser as close allies are named in graft report". 3 July 2020. Archived from the original on 18 August 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ "I Own Weston Hotel, DP William Ruto Says". Citizentv.co.ke. 2 June 2015. Archived from the original on 14 July 2020. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ "State repossesses 1,600-acre land in Ruai linked to Ruto". K24 TV. 23 April 2020. Archived from the original on 14 July 2020. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ "Kenya's post-election violence: ICC Prosecutor presents cases against six individuals for crimes against humanity" (PDF). Encyclopedia of Things. International Criminal Court. 15 December 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- ^ Decision on the Prosecutor's Application for Summons to Appear for William Samoei Ruto, Henry Kiprono Kosgey and Joshua Arap Sang (PDF), International Criminal Court Pre-Trial Chamber II, archived (PDF) from the original on 16 June 2013, retrieved 12 July 2011

- ^ Ruto explains Kiambaa Archived 10 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine Wikileaks

- ^ "Kenya's deputy president William Ruto targeted by gunmen". Sky News. 29 July 2017. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ "Kenya Deputy President Ruto's home entered by knifeman". BBC News. 29 July 2017. Archived from the original on 11 May 2019. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ^ "More police sent to fight attacker at DP Ruto's home". Daily Nation. 30 July 2017. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ "Kenya police kill gunman at Deputy President Ruto's home". Citifm Online. 30 July 2017. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ "One On One With Kenya's Second Most Powerful Woman: Rachel Chebet Ruto". Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 15 August 2022 – via www.youtube.com.

External links

- BBC News, Kenya's political punch-up

- Kahura, Dauti; Akech, Akoko (6 November 2020). "Hustler mentality". africasacountry.com. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- William Ruto, William Ruto – Profile and Biography

- Mboche Obute, Bottom up economic model

- [1]

- 1966 births

- Jubilee Party politicians

- Kalenjin people

- Kenya African National Union politicians

- Kenyan Christians

- Living people

- Members of the National Assembly (Kenya)

- Ministers of Agriculture of Kenya

- People from Rift Valley Province

- People indicted by the International Criminal Court

- United Republican Party (Kenya) politicians

- University of Nairobi alumni

- Vice-presidents of Kenya