Cajun English

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2011) |

Cajun English, or Cajun Vernacular English, is the dialect of English spoken by Cajuns living in Southern Louisiana. Cajun English is significantly influenced by Louisiana French, the historical language of the Cajun people, a subset of Louisiana Creoles—although many today prefer not to identify as such—who descend largely from the Acadian people expelled from the Maritime provinces during Le Grand Dérangement (among many others). It is derived from Louisiana French and is on the list of dialects of the English language for North America. Louisiana French differs, sometimes markedly, from Metropolitan French in terms of pronunciation and vocabulary, partially due to unique features in the original settlers' dialects and partially because of the long isolation of Louisiana Creoles (including Cajuns) from the greater francophone world.

English is now spoken by the vast majority of the Cajun population, but French influence remains strong in terms of inflection and vocabulary. Their accent is considerably distinct from other General American accents.[1] Cajun French is considered by many to be an endangered language, mostly used by elderly generations.[2] However, French in Louisiana is now seeing something of a cultural renaissance.[3]

History

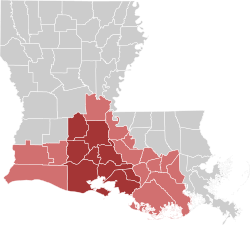

Cajun English is spoken throughout Acadiana. Its speakers are often descendants of Acadians from Nova Scotia, Canada, who in 1755 migrated to French-owned Louisiana after the British took control of Nova Scotia and expelled them from their land.[4] In 1803 however, the United States purchased the territory of Louisiana and, in 1812, when Louisiana drafted their first state Constitution in order to be granted statehood, the English language received official sanction as the language of promulgation and preservation of laws.[5] Despite this change, many Cajuns at the time who lived in small towns and were poorly educated, continued to use French exclusively.[2] This isolated them, subjecting them to ridicule and treatment as second-class citizens. In the 1930s, English was the only language taught in schools and students who spoke French were punished and humiliated in front of their class. The Cajuns still continued to use Cajun French at home and in their communities, but this led to a stigma being associated with the language, and, as a result, parents stopped teaching it to their children.[6] The combination of being native French speakers, and the incomplete English that the Cajun children were learning during their inconsistent public education, led to the advent of Cajun English, a fusion of both languages.[2]

Many decades later, new generations of Cajuns perceived a loss of cultural identity, and their efforts to recover it started the Cajun Renaissance.[2] The corresponding popularity of Cajun food, music, and festivities have been well received by tourists and some programs are now supported by the state government. Although Cajun English has made a comeback, the bilingualism that originally created it, a knowledge of both French and English, has not. Cajun English speakers today typically do not speak French, and experts believe that it is unlikely that this part of the culture will be recovered.[2] This shift away from bilingualism has changed the source of many of the phonological differences between Cajun English and Standard American English from interference caused by being a native French speaker to markers of Cajun identity.[7]

Phonology

| English diaphoneme | Cajun phoneme | Example words |

|---|---|---|

| Pure vowels (Monophthongs) | ||

| /æ/ | [æ] | act, pal, trap, ham, pass |

| /ɑː/ | [ɑ] | blah, bother, father,

lot, top, wasp |

| /ɒ/ | ||

| [a] | all, dog, bought,

loss, saw, taught | |

| /ɔː/ | ||

| /ɛ/ | [ɛ~æ] | dress, met, bread |

| [ɪ] | hem, pen | |

| [i] | length | |

| /ə/ | [ə] | about, syrup, arena |

| /ɪ/ | [ɪ] | hit, skim, tip |

| /iː/ | [i] | beam, chic, fleet |

| (/i/) | [ɪ~i] | happy, very |

| /ʌ/ | [ʌ] | bus, flood, what |

| /ʊ/ | [ʊ] | book, put, should |

| /uː/ | [u] | food, glue, new |

| Diphthongs | ||

| /aɪ/ | [ɑɪ~aː] | ride, shine, try,

bright, dice, pike |

| /aʊ/ | [aʊ~aː] | now, ouch, scout |

| /eɪ/ | [eː] | lake, paid, rein |

| /ɔɪ/ | [ɔɪ] | boy, choice, moist |

| /oʊ/ | [oː] | goat, oh, show |

| R-colored vowels | ||

| /ɑːr/ | [ɑ~a] | barn, car, park |

| /ɛər/ | [ɛ~æ] | bare, bear, there |

| /ɜːr/ | [ʌə~ʌɹ] | burn, first, herd |

| /ər/ | [əɹ] | doctor, martyr, pervade |

| /ɪr/ | [i~ɪ] | fear, peer, tier |

| /ɪər/ | ||

| /ɔːr/ | [ɔə~ɔɹ] | hoarse, horse, war |

| /ɒr/ | [ɑ~ɔ] | orange, tomorrow |

| /ʊər/ | [uə~ʊə] | poor, score, tour |

| /jʊər/ | cure, Europe, pure | |

Cajun English is distinguished by some of the following phonological features:

- The deletion of any word's final consonant (or consonant cluster), and nasal vowels, are common, both features being found in French. Therefore, hand becomes [hæ̃], food becomes [fu], rent becomes [ɹɪ̃], New York becomes [nuˈjɔə], and so on.[8]

- As a consequence of the removal of a word's final consonant the third person singular (-S) and the past tense morpheme (-ED) tend to be dropped. So, 'He give me six' and 'She go with it' rather than 'gives' and 'goes'. And 'I stay two months' and 'She wash my face' rather than 'stayed' and 'washed'.[2]

- Cajun English also has the tendency to drop the auxiliary verb 'to be' in the third person singular (IS) and the second person singular and plurals. For example, 'She pretty' and 'What we doing'.

- The typical American gliding vowels [oʊ] (as in boat), [eɪ] (as in bait), [ʊu] (as in boot), [aʊ~æʊ] (as in bout), [äɪ] (as in bite), and [ɔɪ] (as in boy) have reduced glides or none at all: respectively, [oː], [eː], [uː], [aː~æː], [äː], and [ɔː]. [8]

- Many vowels which are distinct in General American English are pronounced the same way due to a merger; for example, the words hill and heel are homophones, both being pronounced /hɪɹl/[citation needed].

- H-dropping, wherein words that begin with the letter /h/ are pronounced without it, so that hair sounds like air, and so on.[2]

Non-rhoticity, unlike most of the American south, cajun accents tend to drop r after vowel sounds.

- Stress is generally placed on the second or last syllable of a word, a feature inherited directly from French.

- The voiceless and voiced alveolar stops /t/ and /d/ often replace dental fricatives, a feature used by both Cajun English speakers and speakers of Louisiana Creole French (Standard French speakers generally produce alveolar fricatives in the place of dental fricatives). Examples include "bath" being pronounced as "bat" and "they" as "day." This feature leads to a common Louisianian paradigm 'dis, dat, dese, dose' rather than 'this, that, these, those' as a method of describing how Cajuns speak.[2]

- Cajun English speakers generally do not aspirate the consonants /p/, /t/, or /k/. As a result, the words "par" and "bar" can sound very similar to speakers of other English varieties. It is notable that after the Cajun Renaissance, this feature became more common in men than women, with women largely or entirely dropping this phonological feature.[7]

- The inclusion of many loanwords, calques, and phrases from French, such as "nonc" (uncle, from Louisiana French noncle, and Standard French oncle), "cher\chère" (dear, pronounced /ʃɛr/, from the French cher), and "making groceries" (to shop for groceries, a calque of the Cajun French faire des groceries (épicerie)).

French-influenced Cajun vocabulary

- Lagniappe : Gratuity provided by a shop owner to a customer at the time of purchase; something extra

- Allons ! : Let's go!

- Alors pas : Of course not

- Fais do-do : Refers to a dance party, a Cajun version of a square dance. In French, this means to go to sleep.

- Dis-moi la vérité ! : Tell me the truth!

- Quoi faire ? : Why?

- Un magasin : A store

- Être en colère : To be angry

- Mo chagren : I'm sorry

- Une sucette : A pacifier

- Une piastre : A dollar

- Un caleçon : Boxers

- cher (e is pronounced like a in apple) : Dear or darling - also used as "buddy" or "pal"

- Mais non, cher ! : Of course not, dear!

Some variations from Standard English

There are several phrases used by Cajuns that are not used by non-Cajun speakers. Some common phrases are listed below:

Come see

"Come see" is the equivalent of saying "come here" regardless of whether or not there is something to "see." The French "viens voir," or "venez voir," meaning "come" or "please come," is often used in Cajun French to ask people to come.[9] This phrasing may have its roots in "viens voir ici" (IPA: [isi]), the French word for "here."[citation needed]

When you went?

Instead of "When did you go?"

Save the dishes

To "save the dishes" means to "put away the dishes into cupboards where they belong after being washed". While dishes are the most common subject, it is not uncommon to save other things. For example: Save up the clothes, saving the tools, save your toys.

Get/Run down at the store

"Getting/Running down at the store" involves stepping out of a car to enter the store. Most commonly, the driver will ask the passenger, "Are you getting/running down (also)?" One can get down at any place, not just the store. The phrase "get down" may come from the act of "getting down from a horse" as many areas of Acadiana were only accessible by horse well into the 20th century. It also may originate from the French language descendre meaning to get down, much as some English-Spanish bilingual speakers say "get down," from the Spanish bajar.

Makin' (the) groceries

"Makin' groceries" refers to the act of buying groceries, rather than that of manufacturing them. The confusion originates from the direct translation of the American French phrase "faire l'épicerie" which is understood by speakers to mean "to do the grocery shopping." "Faire" as used in the French language can mean either "to do" or "to make." This is a term frequently used in New Orleans, but it's not used very much elsewhere in the Acadiana area.[10]

Make water

"Making water" is using the bathroom, specifically with reference to urination.[clarification needed] One would say, "I need to go make water." It's mostly used in New Orleans.

"for" instead of "at"

Cajun English speakers can exhibit a tendency to use "for" instead of "at" when referring to time. For example, "I'll be there for 2 o'clock." means "I'll be there at 2 o'clock." Given the connection between Cajun English and Acadia, this is also seen among Canadian English speakers.

In popular culture

Television

- In the television series Treme, Cajun English is often used by most of the characters.

- In the television series True Blood, the character René Lernier has a Cajun accent.

- In X-Men : The Animated Series, the character Gambit was introduced as from Louisiana and is known to speak in a thick "Cajun" accent.

- In the television miniseries Band of Brothers, the company's medic Eugene Roe is half-Cajun and speaks with a distinct accent.

- Likewise, Merriell "Snafu" Shelton from a companion miniseries The Pacific.

- In the television series Swamp People, Troy Landry speaks with a strong accent.

- In the Heat of the Night: Season 2, Episode 12; "A.K.A. Kelly Kay"; Jude Thibodeaux ( Kevin Conway ) comes to Sparta in search of a former prostitute he controlled in New Orleans. Cajun accent is prominent.[11]

- Adam Ruins Everything features a recurring bit-character who speaks in a Cajun dialect, with subtitles.

- King of the Hill, has one of Hank Hill's friends Bill Dauterive and his cousin Gilbert, both speaking in Cajun accents, through the latter speaks more stereotypically, than Bill.

Film

- In the movie The Big Easy, Cajun English is used by most of the characters.

- In the movie The Green Mile, Eduard Delacroix (played by Michael Jeter) speaks Cajun English.

- In the animated film The Princess and the Frog, Ray the Firefly (voiced by Jim Cummings) speaks Cajun English.

- In the film Deepwater Horizon, Donald Vidrine (played by John Malkovich) speaks Cajun English.

- In The Blind Side, Ed Orgeron, a Cajun who coached the film and book's subject Michael Oher during the latter's college career, plays himself and uses his native dialect.

- In the film The Waterboy, Cajun English is spoken throughout.

Video games

- Several characters of Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Fathers, particularly the narrator, have Cajun accents. Some characters even use Cajun French phrases.

- Virgil from Left 4 Dead 2, speaking with a Cajun-accent and using few Cajun English wording, during the Swamp Fever finale to The Parish beginning campaigns.

See also

- Acadia, former home of the Cajuns, located in what is now eastern Canada

- Acadiana, A 22-parish region in southern Louisiana

- Acadian French, the dialect of French from which Cajun French derives

- American English

- Cajun

- Cajun French

- Dialects of the English Language

- Franglais, a term sometimes used to describe a mixed vernacular of French and English

- Louisiana Creole French, a French-based creole which has had some influence on Cajun French and English

- Yat, another Louisiana dialect of English

Resources

References

- ^ Do You Speak American . Sea to Shining Sea. American Varieties: Cajun | PBS

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ramos, Raúl Pérez (2012). "Cajun Vernacular English A Study Over A Reborn Dialect" (PDF). Fòrum de Recerca. 17: 623–632.

- ^ "United States: In Louisiana, Cajuns are keen to preserve their identity - YouTube". www.youtube.com. Archived from the original on 2021-12-13. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- ^ "Acadian Expulsion (the Great Upheaval) | The Canadian Encyclopedia". www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- ^ "The French Language in Louisiana Law and Legal Education: A Requiem".

- ^ "Cajun French Efforting Comeback in Louisiana". wafb.com. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- ^ a b Dubois, Sylvie (2000). "When the music change, you change too: Gender and language change in Cajun English". Language Variation and Change. 11 (3): 287–313. doi:10.1017/S0954394599113036.

- ^ a b Dubois & Horvath 2004, pp. 409–410.

- ^ Valdman 2009, p. 655.

- ^ "How to Say to do in French".

- ^ "A.K.A. Kelly Kay". IMDb.

Bibliography

- Dubois, Sylvia; Horvath, Barbara (2004). Kortmann, Bernd; Schneider, Edgar W. (eds.). "Cajun Vernacular English: phonology". A Handbook of Varieties of English: A Multimedia Reference Tool. New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Valdman, Albert (2009). Dictionary of Louisiana French. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9781604734034.