Fëanor

| Fëanor | |

|---|---|

| Tolkien character | |

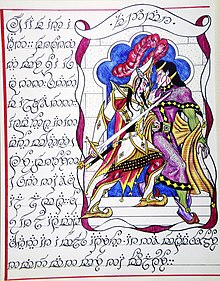

Fëanor (left) threatens Fingolfin Artwork by Tom Loback, 2007 | |

| In-universe information | |

| Aliases | Fëanáro, Curufinwë |

| Race | Elves |

| Book(s) | The Silmarillion (1977) |

Fëanor (IPA: [ˈfɛ.anɔr]) is a fictional character in J. R. R. Tolkien's The Silmarillion. He creates the three Silmarils, the skilfully-forged jewels that give the book their name and theme, triggering division and destruction. He was the eldest son of Finwë, the King of the Noldor, and his first wife Míriel.

Fëanor's Silmarils form a central theme of The Silmarillion as the human and elvish characters battle with the forces of evil for their possession. After the Dark Lord Morgoth steals the Silmarils, Fëanor and his seven sons swear the Oath of Fëanor, vowing to fight anyone and everyone—whether Elf, Man, Maia, or Vala—who withhold the Silmarils.

The oath commanded Fëanor and his sons to press to Middle-earth, in the process committing atrocities, the first Kinslaying, against their fellow Elves at the havens of the Teleri. Fëanor died soon after his arrival in Middle-earth, but his sons were united in the cause of defeating Morgoth and retrieving the Silmarils. Though they lived on in relative harmony with the Eldar of Beleriand for the greater part of the First Age, they committed further Kinslayings against their fellow Elves, and their wayward actions defined the fate of Beleriand.

Scholars have seen Fëanor's pride as Biblical, alongside Morgoth's corruption of elves and men as reflecting Satan's temptation of Adam and Eve, and the desire for godlike knowledge as in the Garden of Eden. Others have likened Fëanor to the Anglo-Saxon leader Byrhtnoth whose foolish pride led to defeat and death at the Battle of Maldon. Tom Shippey writes that the pride is specifically a desire to make things that reflect their own personality, and likens this to Tolkien's own desire to sub-create. John Ellison further likens this creative pride to that of the protagonist in Thomas Mann's 1947 novel Doctor Faustus, noting that both that novel and Tolkien's own legendarium were responses to World War.

Fictional history

Early life

Fëanor's mother, Míriel, died, exhausted, shortly after giving birth.[1] As a result, Fëanor "was made the mightiest in all parts of body and mind: in valour, in endurance, in beauty, in understanding, in skill, in strength and subtlety alike: of all the Children of Ilúvatar, and a bright flame was in him." Finwë would remarry and had several children, including Fëanor's half-brothers Fingolfin and Finarfin, who became prominent leaders among the Noldor.

Fëanor was the student of his father-in-law Mahtan, who was a student of the Vala Aulë. He was a craftsman and gem-smith, inventor of the Tengwar script, and the creator of the palantíri.[note 1]

Silmarils

Fëanor, "in the greatest of his achievements, captured the light of the Two Trees to make the three Silmarils, also called the Great Jewels, though they were not mere glittering stones, they were alive, imperishable, and sacred."[T 2] Even the Valar could not copy them. In fact, Fëanor himself could not copy them, as part of his essence went into their making. Their worth was close to infinite, as they were unique and irreplaceable. So "Varda hallowed the Silmarils so that thereafter no mortal flesh, nor hands unclean, nor anything of evil will might touch them, for it would be scorched and withered."[T 2]

Fëanor prized the Silmarils above all else, and grew suspicious of the Valar and Eldar who he believed coveted them. Melkor, recently released from imprisonment and now residing in Valinor, saw an opportunity to sow dissent among the Noldor. Fëanor refused to communicate with Melkor, but was still caught in his plot. Melkor told Fëanor that his half-brother Fingolfin was planning to usurp his place as heir to Finwë, prompting Fëanor to threaten Fingolfin. As punishment, the Valar exiled Fëanor to Formenos. He took a treasure with him, including the Silmarils, which he put in a locked box. In a show of support, Finwë also withdrew to Formenos.[T 2] Fingolfin took their place as king.

The Valar learnt that Melkor was manipulating Fëanor, and sent Tulkas to capture Melkor, but he had already escaped. Fëanor realised that Melkor's goal was to obtain the Silmarils, "and he shut the doors of his house in the face of the mightiest of all the dwellers in Eä."[T 2] The Valar invited Fëanor and Fingolfin to Valinor to make peace. Fingolfin offered a hand to his half-brother, recognising Fëanor's place as the eldest. Fëanor accepted, but The Two Trees were destroyed by Melkor with the aid of Ungoliant.[T 3] The Valar, realising that now the light of the Trees survived only in the Silmarils, asked Fëanor to give them up so that they could restore the Trees. Fëanor replied: "It may be that I can unlock my jewels, but never again shall I make their like; and if I must break them, I shall break my heart."[T 4] He refused to give up the Silmarils of his own free will. Messengers from Formenos told him that Melkor had killed Finwë and stolen the Silmarils. Yavanna was thus unable to heal the Two Trees.[T 4]

Fëanor named Melkor "Morgoth", "Black Enemy".[T 4] Fëanor railed against the Great Enemy, blaming the Valar for Morgoth's deeds. He persuaded most of his people that because the Valar had abandoned them, the Noldor must follow him to Middle-earth to wrest the Silmarils back from Morgoth and avenge Finwë. Together with his seven sons, they swore the fateful Oath of Fëanor:[T 4]

They swore an oath which none shall break, and none should take, by the name even of Ilúvatar, calling the Everlasting Dark upon them if they kept it not... ...vowing to pursue with vengeance and hatred to the ends of the World Vala, Demon, Elf or Man as yet unborn or any creature, great or small, good or evil, that time should bring forth unto the end of days, whoso should hold or take or keep a Silmaril from their possession. — Quenta Silmarillion

Return to Beleriand

To get to Middle-earth, Fëanor went to the shores of Aman, and asked the seafaring Teleri for their aid. When they refused, Fëanor ordered the Noldor to steal the ships. The Teleri resisted, and many of them were killed. The battle became known as the Kinslaying at Alqualondë, or the first kinslaying.[T 4][3] His sons would commit two other acts of warfare against elves in Middle-earth in his name. In repentance, Finarfin, Finwë's third son, took his host and turned back. They were accepted by the Valar, and Finarfin ruled as High-King of the Noldor in Valinor. The remaining Elves, those who followed Fëanor and Fingolfin, became subject to the Doom of Mandos. There were not enough ships to carry all of the Noldor across the sea, so Fëanor and his sons led the first group.[T 4] Upon arriving at Losgar, in Lammoth in the far west of Beleriand, they decided to burn the ships and leave the followers of Fingolfin behind. Fingolfin led his people for many months to reach Beleriand, travelling by the northern ice.[T 4]

Morgoth summoned his armies from his fortress of Angband and attacked Fëanor's encampment in Mithrim. This battle was called the Battle under the Stars, or Dagor-nuin-Giliath, for the Sun and Moon had not yet been made. The Noldor won the battle. Fëanor pressed on toward Angband with his sons. He came within sight of Angband, but was ambushed by a force of Balrogs, with few elves about him. He fought mightily with Gothmog, captain of the Balrogs. His sons came upon the Balrogs with a great force of elves, and drove them off; but Fëanor knew his wounds were fatal. He cursed Morgoth thrice, but with the eyes of death, he saw that his elves, unaided, would never throw down the dark towers of Thangorodrim. Nevertheless, he told his sons to keep the oath and to avenge their father. When he died, his body turned to ashes.[T 5]

Aftermath

The Oath of Fëanor affected the lovers Beren and Lúthien. They recovered a Silmaril from Morgoth. Their son Dior inherited it, but it awoke the oath and caused the Sons of Fëanor to make war on the Elves of Doriath when Dior refused to give up the Silmaril. The brothers killed Dior and sacked the halls of the Sindar, the second Kinslaying, where three of their number—Celegorm, Curufin, and Caranthir—died. The Silmaril escaped the destruction of Doriath, and the oath drove the remaining sons onwards. When the Sons of Fëanor learned that it was possessed by Elwing, daughter of Dior, they attacked after Elwing also refused to return the Silmaril to them, the third and final Kinslaying where Amras was slain.[T 6]

The Silmaril escaped them again and was borne by Eärendil into the West.[T 7] That Silmaril was lost to the Sons of Fëanor, but two more remained inside the crown of Morgoth. At the end of the War of Wrath the two surviving oath-takers, Maedhros and Maglor, stole the two Silmarils from the camp of the victorious Hosts of Valinor. Due to the terrible deeds committed by the brothers in their retrieval of the Silmarils, they could not handle the Silmarils without enduring searing pain. The two brothers parted: in their anguish Maedhros threw himself and his Silmaril into a fiery chasm, while Maglor cast his Silmaril into the sea, spending eternity wandering the shore, lamenting his fate.[T 7]

According to Mandos' prophecy, following Melkor's final return and defeat in the Dagor Dagorath, the world will be changed and the Valar will recover the Silmarils. Fëanor will be released from the Halls of Mandos and give Yavanna the Silmarils. Depending on the version of the story, either she or Fëanor will break them, and Yavanna will revive the Two Trees. The Pelóri Mountains will be flattened and the light of the Two Trees will fill the world in eternal bliss.[T 8][T 9]

House of Fëanor

| Mahtan | Míriel | Finwë of the Noldor | Indis of the Vanyar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nerdanel | Fëanor maker of Silmarils | Findis | Fingolfin | Írimë | Finarfin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maedhros | Maglor | Celegorm | Caranthir | Curufin | Amrod | Amras | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Celebrimbor maker of Rings | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![]() Kings of the Noldor in Valinor

Kings of the Noldor in Valinor

![]() High Kings of the Noldor in Exile (in Middle-earth)

High Kings of the Noldor in Exile (in Middle-earth)

All the characters shown are Elves.

Development

Fëanor was originally named Curufinwë ("skilful [son of] Finwë") in Tolkien's fictional language of Quenya. He is known as Fëanáro, "spirit of fire" in Quenya, from fëa ("spirit") and nár ("flame"). Fëanáro is his "mother-name" or Amilessë, the name given by an Elf's mother at, or some years after, birth and it was one of their true names.[T 10]

Tolkien wrote at least four versions of the Oath of Fëanor itself, as found in The History of Middle-earth. The three earliest versions are found in The Lays of Beleriand: in alliterative verse (circa 1918–1920s), in chapter 2, "Poems Early Abandoned" The Flight of the Noldoli from Valinor. Lines 132–141; in rhyming couplets (circa 1928), in chapter 3, "The Lay of Leithian". Canto VI, lines 1628–1643; and in a different form as restated by Celegorm, third son of Fëanor, in chapter 3, "The Lay of Leithian." Canto VI, lines 1848–1857. A later version is found in Morgoth's Ring. Fëanor is among those major characters whom Tolkien, who also used to illustrate his writings, supplied with a distinct heraldic device.[4]

Analysis

Foolish pride

The Tolkien scholar Jane Chance sees Fëanor's pride as Biblical, writing that Morgoth's corruption of elves and men "mirrors that of Adam and Eve by Satan; the desire for power and godlike being is the same desire for knowledge of good and evil witnessed in the Garden of Eden."[6] She treats the Silmarils as symbols of that same desire, identifying Fëanor's wish to be like the Valar in creating "things of his own" as rebellious pride, and pointing out that his rebellion is echoed by that of the Numenorean man Ar-Pharazon, and then at the end of The Silmarillion by the (angelic) Maia, Sauron, who becomes the Dark Lord of The Lord of the Rings.[6]

The philologist Elizabeth Solopova suggests that the character of Fëanor was inspired by Byrhtnoth from the Anglo-Saxon poem "The Battle of Maldon" who is slain in battle. Tolkien has described Byrhtnoth as misled by "pride and misplaced chivalry proven fatal" and as "too foolish to be heroic",[T 11] and Fëanor is driven by "overmastering pride" that causes his own death and that of countless followers.[5]

Pride in sub-creation

The Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey comments that Fëanor and his Silmarils relate to The Silmarillion's theme in a particular way: the sin of the elves is not human pride, as in the Biblical fall, but their "desire to make things which will forever reflect or incarnate their own personality". This elvish form of pride leads Fëanor to forge the Silmarils, and, Shippey suggests, led Tolkien to write his fictions: "Tolkien could not help seeing a part of himself in Fëanor and Saruman, sharing their perhaps licit, perhaps illicit desire to 'sub-create'."[7]

John Ellison, writing in Mallorn, draws a comparison between Fëanor's ultimately self-destructive pride and that of Adrian Leverkühn, the protagonist in Thomas Mann's 1947 novel Doctor Faustus: The Life of the German Composer Adrian Leverkühn, Told by a Friend. In his view, the life history of both characters is of "genius corrupted finally into insanity; the creative drive turns on its possessor and destroys him, and with him a good part of the fabric of society."[8] He describes as parallel Mann's depiction of Leverkühn in a collapsing Nazi Germany and Tolkien's starting his mythology amidst the collapse of pre-1914 Europe: he likens the "Good German" narrator Zeitblom (who does not support the Nazis) to one of "the Faithful" (like Elendil) among the gone-to-bad Númenóreans. Fëanor is, he writes, not an exact equivalent of Doctor Faustus: he does not make a pact with the devil; but both Fëanor and Leverkühn outgrow their teachers in creative skill. Ellison calls Leverkühn "a Fëanor of our times", and comments that far from being a simple battle of good versus evil, Tolkien's world as seen in Fëanor has "the creative and destructive forces in man's nature ... indivisibly linked; this is the essence of the 'fallen world' in which we live."[8]

Like Shippey, Ellison relates Fëanor's making of the Silmarils to what he supposes was Tolkien's own belief: that it was "a dangerous and impermissible act" that went beyond what the Creator had intended for the Elves. Further, Ellison suggests that while Fëanor does not directly represent Tolkien, there is something about his action that can be applied to Tolkien's life. Tolkien calls Fëanor "fey"; Ellison notes that Tolkien analysed his own name as tollkühn, with the same meaning. Further, Tolkien seems, Ellison writes, to have felt a conflict between his own "sub-creation" and his Catholic faith. He worked out and justified his fantasy writing in his essay On Fairy-Stories: the creative artist may have had a subordinate role but all the same, sub-creation was "supremely important". Ellison notes that Tolkien was disinclined to finish any of his works: he had to be pushed to complete The Hobbit and "did not think of The Lord of the Rings as something independently complete in itself", but as the last part of "a triptych", the rest of which (his legendarium) "remained unfilled" in his lifetime.[8]

In popular culture

The black metal band Summoning's album Oath Bound's name comes from the Oath of Fëanor;[9] the lyrics are about the Quenta Silmarillion. Blind Guardian's song "The Curse of Fëanor", featured on the album Nightfall in Middle Earth, tells of Fëanor swearing to go after Morgoth.[10][11] The Russian power metal band Epidemia has a song entitled "Feanor" about the character's campaign against Morgoth, and his death.[12]

See also

Notes

References

Primary

- This list identifies each item's location in Tolkien's writings.

- ^ Tolkien 1977, Chapter 6 "Of Fëanor and the Unchaining of Melkor"

- ^ a b c d Tolkien 1977, Chapter 7, "Of the Silmarils and the Unrest of the Noldor"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, Chapter 8, "Of the Darkening of Valinor"

- ^ a b c d e f g Tolkien 1977, Chapter 9, "Of the Flight of the Noldor"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, Chapter 13, "Of the Return of the Noldor"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, Chapter 19, "Of Beren and Lúthien"

- ^ a b Tolkien 1977, Chapter 24, "Of the Voyage of Eärendil"

- ^ Tolkien 1986, ch. 3: "Quenta Noldorinwa"

- ^ Tolkien 1994, Part 2, "The Later Quenta Silmarillion", "The Last Chapters of the Quenta Silmarillion"

- ^ Tolkien 1996, Chapter 11 "The Shibboleth of Fëanor"

- ^ Tolkien 1966, pp. 4, 22

Secondary

- ^ Dickerson, Matthew (2013) [2007]. "Popular Music". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). Finwë and Míriel. The J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 212–213. ISBN 978-0-415-96942-0.

- ^ Clark, George; Timmons, Daniel (2000). J. R. R. Tolkien and his Literary Resonances. Greenwood Press. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-313-30845-1.

- ^ Fontenot, Megan (7 March 2019). "Exploring the People of Middle-earth: Míriel, Historian of the Noldor (Part 1)". Tor.com. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ Hammond, Wayne G.; Scull, Christina (1995). J. R. R. Tolkien: Artist and Illustrator. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-74816-9.

- ^ a b Solopova, Elizabeth (2009). Languages, Myths and History: An Introduction to the Linguistic and Literary Background of J. R. R. Tolkien's Fiction. New York City: North Landing Books. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-9816607-1-4.

- ^ a b Nitzsche, Jane Chance (1980) [1979]. Tolkien's Art. Papermac. pp. 131–133. ISBN 0-333-29034-8.

- ^ Shippey, Tom (1982). The Road to Middle-Earth. Grafton (HarperCollins). pp. 213–216. ISBN 0261102753.

- ^ a b c d Ellison, John (July 2003). "From Fëanor to Doctor Faustus: a creator's path to self destruction". Mallorn (41): 13–21. JSTOR 45320486.

- ^ Summoning | Interview | Lords Of Metal metal E-zine - Issue 58: April 2006

- ^ Eden, Bradford Lee (2010). Middle-earth Minstrel: Essays on Music in Tolkien. McFarland. p. 134. ISBN 9780786456604.

- ^ Robb, Brian J.; Simpson, Paul (2013). Middle-earth Envisioned: The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings: On Screen, On Stage, and Beyond. Race Point Publishing. p. 185. ISBN 978-1627880787.

- ^ "Феанор (Feanor) (English translation)". Lyrics Translate. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

Sources

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1966). The Tolkien Reader. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-34506-1.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1977). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Silmarillion. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-25730-2.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1986). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Shaping of Middle-earth. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-42501-5.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1994). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The War of the Jewels. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-71041-3.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1996). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Peoples of Middle-earth. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-82760-4.