Merlin

| Merlin | |

|---|---|

| Matter of Britain character | |

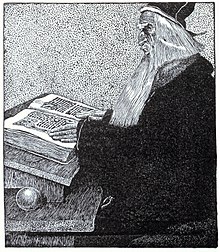

The Enchanter Merlin, Howard Pyle's illustration for The Story of King Arthur and His Knights (1903) | |

| First appearance | Prophetiae Merlini |

| Created by | Geoffrey of Monmouth |

| Based on | Myrddin Wyllt and Ambrosius Aurelianus |

| In-universe information | |

| Occupation | Prophet, magician, bard, royal advisor, warrior, others (depending on the source)[note 1] |

| Spouse | Gwendolen |

| Significant other | Lady of the Lake, Morgan le Fay, Sebile (romance tradition) |

| Relatives | Ganieda |

| Home | "Esplumoir Merlin" |

Merlin (Welsh: Myrddin, Cornish: Marzhin, Breton: Merzhin) is a mythical figure prominently featured in the legend of King Arthur and best known as a magic man, among his various other roles.[note 2] His usual depiction, based on an amalgamation of historic and legendary figures, was introduced by the 12th-century British author Geoffrey of Monmouth. It is believed that Geoffrey combined earlier tales of Myrddin and Ambrosius, two legendary Briton prophets with no connection to Arthur, to form the composite figure called Merlinus Ambrosius (Welsh: Myrddin Emrys, Breton: Merzhin Ambroaz). Geoffrey's rendering of the character became immediately popular, especially in Wales.[3] Later writers in France and elsewhere expanded the account to produce a fuller image, creating one of the most important figures in the imagination and literature of the Middle Ages.

Merlin's traditional biography casts him as a being born of a mortal woman, sired by an incubus, from whom he inherits his supernatural powers and abilities,[4] most commonly and notably prophecy and shapeshifting. Merlin matures to an ascendant sagehood and engineers the birth of Arthur through magic and intrigue.[5] Later authors have Merlin serve as the king's advisor and mentor until he disappears from the story after having been bewitched and forever sealed or killed by his student known as the Lady of the Lake after falling madly in love with her, leaving behind a series of prophecies foretelling the events yet to come. He is popularly said to be buried in the magical forest of Brocéliande.[6]

Name

The name "Merlin" is derived from the Brythonic Myrddin, the name of the bard who was one of the chief sources for the later legendary figure. Geoffrey of Monmouth Latinised the name to Merlinus in his works. Medievalist Gaston Paris suggests that Geoffrey chose the form Merlinus rather than the expected *Merdinus to avoid a resemblance to the Anglo-Norman word merde (from Latin merda) for feces.[7] A more plausible suggestion is that 'Merlin' is an adjective and that consequently we should be speaking of "The Merlin", from the French merle meaning 'blackbird',[8]: 79 or that the 'many names' deriving from Myrddin stem from the Welsh: myrdd: myriad.[9][10] There have been other suggestions deriving the name Myrddin from Celtic languages, including that of a combination of *mer (mad) and the Welsh dyn (man), to mean 'madman'.[11] In his Myrdhinn, ou l'Enchanteur Merlin (1862), La Villemarqué wished to derive the form Marz[h]in from marz, the Breton word for miracle; Villemarqué furthermore associated it with the marte, a type of fairy being from the French folklore.

Clas Myrddin or Merlin's Enclosure is an early name for Great Britain stated in the Third Series of Welsh Triads.[12] Celticist A. O. H. Jarman suggests that the Welsh name Myrddin (Welsh pronunciation: [ˈmərðin]) was derived from the toponym Caerfyrddin, the Welsh name for the town known in English as Carmarthen.[13] This contrasts with the popular folk etymology that the town was named after the bard. The name Carmarthen is derived from the town's previous Roman name Moridunum,[7][13] in turn derived from Celtic Brittonic moridunon, 'sea fortress'.[14]

Medieval legend

Geoffrey and his sources

Geoffrey's composite Merlin is based mostly on the North Brythonic poet and seer Myrddin Wyllt, that is "Myrddin the Wild" (known as Merlinus Caledonensis or Merlin Sylvestris in later texts influenced by Geoffrey). Myrddin's legend has parallels with a Welsh and Scottish story of the mad prophet Lailoken (Laleocen), and with Buile Shuibhne, an Irish tale of the wandering insane king Suibhne (Sweeney).[8]: 58 In Welsh poetry, Myrddin was a bard driven mad after witnessing the horrors of war, who fled civilization to become a wild man of the wood in the 6th century.[9] He roams the Caledonian Forest, until cured of his madness by Kentigern (Saint Mungo). Geoffrey had Myrddin in mind when he wrote his earliest surviving work, the Prophetiae Merlini ("Prophecies of Merlin", c. 1130), which he claimed were the actual words of the legendary poet, however revealing little about Merlin's background.

Geoffrey was also further inspired by Emrys (Old Welsh: Embreis), a character based in part on the 5th-century historical figure of the Romano-British war leader Ambrosius Aurelianus.[15] When Geoffrey included Merlin in his next work, Historia Regum Britanniae (c. 1136), he supplemented his characterisation by attributing to Merlin stories concerning Ambrosius, taken from one of his primary sources, the early 9th-century Historia Brittonum attributed to Nennius. In Nennius' account, Ambrosius was discovered when the British king Vortigern attempted to erect a tower at Dinas Emrys. More than once, the tower collapsed before completion. Vortigen's wise men advised him that the only solution was to sprinkle the foundation with the blood of a child born without a father. Ambrosius was rumoured to be such a child. When brought before the king, Ambrosius revealed that below the foundation of the tower was a lake containing two dragons battling into each other, representing the struggle between the invading Saxons and the native Celtic Britons. Geoffrey retold the story in his Historia Regum Britanniæ, adding new episodes that tie Merlin with King Arthur and his predecessors. Geoffrey stated that this Ambrosius was also called "Merlin", therefore Ambrosius Merlinus, and kept him separate from Aurelius Ambrosius.

Therefore, Geoffrey's account of Merlin Ambrosius' early life is based on the story from the Historia Brittonum. Geoffrey added his own embellishments to the tale, which he set in Carmarthen, Wales (Welsh: Caerfyrddin). While Nennius' "fatherless" Ambrosius eventually reveals himself to be the son of a Roman consul, Geoffrey's Merlin is begotten by an incubus demon on a daughter of the King of Dyfed (Demetae, today's South West Wales). Usually, the name of Merlin's mother is not stated, but is given as Adhan in the oldest version of the Prose Brut,[16] the text also naming his grandfather as King Conaan.[17] The story of Vortigern's tower is the same; the underground dragons, one white and one red, represent the Saxons and the Britons, and their final battle is a portent of things to come. At this point Geoffrey inserted a long section of Merlin's prophecies, taken from his earlier Prophetiae Merlini. He told two further tales of the character. In the first, Merlin creates Stonehenge as a burial place for Aurelius Ambrosius, bringing the stones from Ireland.[note 3] In the second, Merlin's magic enables the new British king Uther Pendragon to enter into Tintagel Castle in disguise and to father his son Arthur with his enemy's wife, Igerna (Igraine). These episodes appear in many later adaptations of Geoffrey's account. As Lewis Thorpe notes, Merlin disappears from the narrative subsequently. He does not tutor and advise Arthur as in later versions.[5]

Geoffrey dealt with Merlin again in his third work, Vita Merlini (1150). He based it on stories of the original 6th-century Myrddin, set long after his time frame for the life of Merlin Ambrosius. Geoffrey asserts that the characters and events of Vita Merlini are the same as told in the Historia Regum Britanniae. Here, Merlin survives the reign of Arthur, about the fall of whom he is told by Taliesin. Merlin spends a part of his life as a madman in the woods and marries a woman named Guendoloena (a character inspired by the male Gwenddoleu ap Ceidio).[5]: 44 He eventually retires to observing stars from his house with seventy windows in the remote woods of Rhydderch. There, he is often visited by Taliesin and by his own sister Ganieda (Geoffrey's character based on Myrddin's sister Gwenddydd), who has become queen of the Cumbrians and is also endowed with prophetic powers.

Nikolai Tolstoy hypothesized that Merlin is based on a historical personage, probably a 6th-century druid living in southern Scotland. His argument was based on the fact that early references to Merlin describe him as possessing characteristics which modern scholarship (but not that of the time the sources were written) would recognize as druidical, the inference being that those characteristics were not invented by the early chroniclers, but belonged to a real person.[21] If so, the hypothetical Merlin would have lived about a century after the hypothetical historical Arthur. A late version of the Annales Cambriae (dubbed the "B-text", written at the end of the 13th century) and influenced by Geoffrey,[22] records for the year 573, that after "the battle of Arfderydd, between the sons of Eliffer and Gwenddolau son of Ceidio; in which battle Gwenddolau fell; Merlin went mad." The earliest version of the Annales Cambriae entry (in the "A-text", written c. 1100), as well as a later copy (the "C-text", written towards the end of the 13th century) do not mention Merlin.[23] Myrddin/Merlin furthermore shares similarities with the shamanic bard figure of Taliesin, alongside whom he appears in the Welsh Triads and in Vita Merlini, as well as in the poem "Ymddiddan Myrddin a Thaliesin" ("The Conversation between Myrddin and Taliesin") from The Black Book of Carmarthen, which was dated by Rachel Bromwich as "certainly" before 1100, that is predating Vita Merlini by at least half century while telling a different version of the same story.[24] According to Villemarqué, the origin of the legend of Merlin lies with the French figure of Saint Martin of Tours.

Later developments

Sometime around the turn of the following 13th century, Robert de Boron retold and expanded on this material in Merlin, an Old French poem presenting itself as the story of Merlin's life as told by Merlin himself to the author. Only a few lines of what is believed to be the original text have survived, but a more popular prose version had a great influence on the emerging genre of Arthurian-themed chivalric romance. In Robert's account, as in Geoffrey's Historia, Merlin is created as a demon spawn, but here explicitly to become the Antichrist intended to reverse the effect of the Harrowing of Hell.[note 4] The infernal plot is thwarted when a priest (and the story's narrator[note 5]) named Blaise is contacted by the child's mother. Blaise immediately baptizes the boy at birth, thus freeing him from the power of Satan and his intended destiny.[26] The demonic legacy invests Merlin (already able to speak fluently even as a newborn) with a preternatural knowledge of the past and present, which is supplemented by God, who gives the boy a prophetic knowledge of the future. The text lays great emphasis on Merlin's power to shapeshift, on his joking personality, and on his connection to the Holy Grail, the quest for which he foretells. Inspired by Wace's Roman de Brut, an Anglo-Norman adaptation of Geoffrey's Historia, Merlin was originally a part of a cycle of Robert's poems telling the story of the Grail over the centuries. The narrative of Merlin is largely based on Geoffrey's familiar tale of Vortigern's Tower, Uther's war against the Saxons, and Arthur's conception. What follows is a new episode of the young Arthur's drawing of the sword from the stone,[27] an event orchestrated by Merlin. Merlin also earlier instructs Uther to establish the original order of the Round Table, after creating the table itself. The prose version of Robert's poem was then continued in the 13th-century Merlin Continuation or the Suite de Merlin, describing King Arthur's early wars and Merlin's role in them,[28] as he predicts and influences the course of battles.[note 6] He also helps Arthur in other ways, including providing him with the magic sword Excalibur through a Lady of the Lake. Here too Merlin's shapeshifting powers feature prominently.[note 7]

The extended prose rendering became the foundation for the Lancelot-Grail, a vast cyclical series of Old French prose works also known as the Vulgate Cycle. Eventually, it was directly incorporated into the Vulgate Cycle as the Estoire de Merlin, also known as the Vulgate Merlin or the Prose Merlin. A further reworking and continuation of the Prose Merlin was included within the subsequent Post-Vulgate Cycle as the Post-Vulgate Suite du Merlin or the Huth Merlin. All these variants have been adapted and translated into several other languages, and further modified. Notably, the Post-Vulgate Suite (along with an earlier version of the Prose Merlin) was the main source for the opening part of Thomas Malory's English-language compilation work Le Morte d'Arthur that formed a now-iconic version of the legend. Compared to his French sources, Malory limited the extent of the negative association of Merlin and his powers, relatively rarely being condemned as demonic by other characters such as King Lot.[31] Conversely, Merlin seems to be inherently evil in the so-called non-cyclic Lancelot, where he was born as the "fatherless child" from not a supernatural rape of a virgin but a consensual union between a lustful demon and an unmarried beautiful young lady, and was never baptized.[32][33] The Prose Lancelot further relates that, after growing up in the borderlands between Scotland (Pictish lands) and Ireland (Argyll), Merlin "possessed all the wisdom that can come from demons, which is why he was so feared by the Bretons and so revered that everyone called him a holy prophet and the ordinary people all called him their god."[34]

As the Arthurian myths were retold, Merlin's prophetic aspects were sometimes de-emphasised in favour of portraying him as a wizard and an advisor to the young Arthur, sometimes in struggle between good and evil sides of his character, and living in deep forests connected with nature. Through his ability to change his shape, he may appear as a "wild man" figure evoking that of his prototype Myrddin Wyllt,[35] as a civilized man of any age, or even as a talking animal.[36][note 8] In the Perceval en prose (also known as the Didot Perceval and too attributed to Robert), where Merlin is the initiator of the Grail Quest and cannot die until the end of days, he eventually retires after Arthur's downfall by turning himself into a bird and entering the mysterious esplumoir, never to be seen again.[37] In the Vulgate Cycle's version of Merlin, his acts include arranging consummation of Arthur's desire for "the most beautiful maiden ever born," Lady Lisanor of Cardigan, resulting in the birth of Arthur's illegitimate son Lohot from before the marriage to Guinevere.[38][39] But fate cannot always be changed: the Post-Vulgate Cycle has Merlin warn Arthur of how the birth of his other son will bring great misfortune and ruin to his kingdom, which then becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Eventually, long after Merlin is gone, his advice to dispose of the baby Mordred through an event evoking the Biblical Massacre of the Innocents leads to the deaths of many, among them Arthur.

The earliest English verse romance concerning Merlin is Of Arthour and of Merlin, which drew from the chronicles and the Vulgate Cycle. In English-language medieval texts that conflate Britain with the Kingdom of England, the Anglo-Saxon enemies against whom Merlin aids first Uther and then Arthur tend to be replaced by the Saracens[40] or simply just invading pagans. Some of the many Welsh works predicting the Celtic revenge and victory over the Saxons have been also reinterpreted as Merlin's (Myrddin's) prophecies, and later used by propaganda of the Welsh-descent king Henry VIII of England in the 16th century. The House of Tudor, which traced their lineage directly to Arthur, interpreted the prophecy of King Arthur's return figuratively as concerning their ascent to the throne of England that they sought to legitimise following the Wars of the Roses.[41]

Many other medieval works dealing with the Merlin legend include an unusual story of the 13th-century Le Roman de Silence.[42] The Prophéties de Merlin (c. 1276) contains long prophecies of Merlin (mostly concerned with 11th to 13th-century Italian history and contemporary politics), some by his ghost after his death, interspersed with episodes relating Merlin's deeds and with assorted Arthurian adventures in which Merlin does not appear at all. It pictures Merlin as a righteous seer chastising people for their sins, as does the 13th-14th Italian story collection Il Novellino which draws heavily from it.[43][44] Even more political Italian text was Joachim of Fiore's Expositio Sybillae et Merlini, directed against Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor whom the author regarded as the Antichrist. The earliest Merlin text written in Germany was Caesarius of Heisterbach's Latin Dialogus Miraculorum (1220). Ulrich Füetrer's 15th-century Buch der Abenteuer, in the section based on Albrecht von Scharfenberg's lost Merlin,[45] presents Merlin as Uter's father, effectively making his grandson Arthur a part-devil too. Merlin's unnamed daughter appears in the First Continuation of Perceval, the Story of the Grail to guide Perceval towards the Grail Castle.

Tales of Merlin's end

In chivalric romance tradition, Merlin has a major weakness that leads him to his relatively early doom: young beautiful women of femme fatale[46] archetype. His apprentice is often Arthur's half-sister Morgan le Fay (in the Prophéties de Merlin along with Sebile and two other witch queens and the Lady of the Isle of Avalon (Dama di Isola do Vallone); the others who have learnt sorcery from Merlin include the Wise Damsel in the Italian Historia di Merlino,[note 9] and the male wizard Mabon in the Post-Vulgate Merlin Continuation and the Prose Tristan). While Merlin does share his magic with his apprentices, his prophetic powers cannot be passed on. As for Morgan, she is sometimes depicted as Merlin's lover[47] and sometimes as just an unrequited love interest.[note 10] Contrary to the many modern works in which they are archenemies, Merlin and Morgan are never opposed to each other in any medieval tradition, other than Morgan forcibly rejecting him in some texts; in fact, his love for Morgan is so great that he even lies to the king in order to save her in the Huth Merlin, which is the only instance of him ever intentionally misleading Arthur.[49][note 11] Instead, Merlin's eventual undoing comes from his lusting after another of his female students: the one often named Viviane, among various other names and spellings, including Malory's (or really his editor Caxton's) now-popular form Nimue (originally Nymue). She is also called a fairy (French fee) like Morgan and described as a Lady of the Lake (the "chief Lady of the Lake" in case of Malory's Nimue). Malory's telling of this episode would later become a major inspiration for Romantic authors and artists of the 19th century.

"How by her subtle working she made Merlin to go under the stone to let wit of the marvels there and she wrought so there for him that he came never out for all the craft he could do."

Viviane's character in relation with Merlin is first found in the Lancelot-Grail cycle, after having been inserted into the legend of Merlin by either de Boron or his continuator. There are many different versions of their story. Common themes in most of them include Merlin actually having the prior prophetic knowledge of her plot against him (one exception is the Spanish Post-Vulgate Baladro where his foresight ability is explicitly dampened by sexual desire[46]) but lacking either ability or will to counteract it in any way, along with her using one of his own spells to rid of him. Usually (including in Le Morte d'Arthur), having learnt everything she could from him, Viviane will then also replace the eliminated Merlin within the story, taking up his role as Arthur's adviser and court mage.[50] However, Merlin's fate of either demise or eternal imprisonment, along with his destroyer or captor's motivation (from her fear of Merlin and protecting her own virginity, to her jealously for his relationship with Morgan), is recounted differently in variants of this motif. The exact form of his either prison or grave can be also variably a cave, a hole under a large rock (as in Le Morte d'Arthur), a magic tower, or a tree.[30] These are usually placed within the enchanted forest of Brocéliande, a legendary location often identified as the real-life Paimpont forest in Brittany.[6]

Niniane, as the Lady of the Lake student of Merlin is known as in the Livre d'Artus continuation of Merlin, is mentioned as having broken his heart prior to his later second relationship with Morgan, but here the text actually does not tell how exactly Merlin did vanish, other than relating his farewell meeting with Blaise. In the Vulgate Lancelot, which predated the later Vulgate Merlin, she (aged just 12 at the time) makes Merlin sleep forever in a pit in the forest of Darnantes, "and that is where he remained, for never again did anyone see or hear of him or have news to tell of him."[51] In the Post-Vulgate Suite de Merlin, the young King Bagdemagus (one of the early Knights of the Round Table) manages to find the rock under which Merlin is entombed alive by Niviene, as she is named there.[note 12] He communicates with Merlin, but is unable to lift the stone; what follows next is supposedly narrated in the mysterious text Conte del Brait (Tale of the Cry).[note 13] In the Prophéties de Merlin version, his tomb is unsuccessfully searched for by various parties, including by Morgan and her enchantresses, but cannot be accessed due to the deadly magic traps around it,[54] while the Lady of the Lake comes to taunt Merlin by asking did he rot there yet.[52] One notably alternate version having a happier ending for Merlin is contained within the Premiers Faits section of the Livre du Graal, where Niniane peacefully confines him in Brocéliande with walls of air, visible only as a mist to others but as a beautiful yet unbreakable crystal tower to him (only Merlin's disembodied voice can escape his prison one last time when he speaks to Gawain[52] on the knight's quest to find him), where they will then spend almost every night together as lovers.[55] Besides evoking the final scenes from Vita Merlini, this particular variant of their story also mirrors episodes found in some other texts, wherein Merlin either is an object of one-sided desire by a different amorous sorceress who too (unsuccessfully) plots to trap him or it is actually Merlin himself who traps an unwilling lover with his magic.[note 14]

Unrelated to the legend of the Lady of the Lake, other purported sites of Merlin's burial include a cave deep inside Merlin's Hill (Welsh: Bryn Myrddin), outside Carmarthen. Carmarthen is also associated with Merlin more generally, including through the 13th-century manuscript known as the Black Book and the local lore of Merlin's Oak. In North Welsh tradition, Merlin retires to Bardsey Island (Welsh: Ynys Enlli), where he lives in a house of glass (Welsh: Tŷ Gwydr) with the Thirteen Treasures of the Island of Britain (Welsh: Tri Thlws ar Ddeg Ynys Prydain).[57]: 200 One site of his tomb is said to be Marlborough Mound in Wiltshire,[58] known in medieval times as Merlebergia (the Abbot of Cirencester wrote in 1215: "Merlin's tumulus gave you your name, Merlebergia"[57]: 93 ). Another site associated with Merlin's burial, in his 'Merlin Silvestris' aspect, is the confluence of the Pausalyl Burn and River Tweed in Drumelzier, Scotland. The 15th-century Scotichronicon tells that Merlin himself underwent a triple-death, at the hands of some shepherds of the under-king Meldred: stoned and beaten by the shepherds, he falls over a cliff and is impaled on a stake, his head falls forward into the water, and he drowns.[note 15] The fulfilment of another prophecy, ascribed to Thomas the Rhymer, came about when a spate of the Tweed and Pausayl occurred during the reign of the Scottish James VI and I on the English throne: "When Tweed and Pausayl meet at Merlin's grave, / Scotland and England one king shall have."[9]: 62

Modern culture

Merlin and stories involving him have continued to be popular from the Renaissance to the present day, especially since the renewed interest in the legend of Arthur in modern times. As noted by Arthurian scholar Alan Lupack, "numerous novels, poems and plays centre around Merlin. In American literature and popular culture, Merlin is perhaps the most frequently portrayed Arthurian character."[59] Diverging from his traditional role in the legends, Merlin is sometimes portrayed as a villain, as in Mark Twain's humorous novel A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (1889).[59] According to Peter H. Goodrich in Merlin: A Casebook:

Merlin's primary characteristics continue to be recalled, refined, and expanded today, continually encompassing new ideas and technologies as well as old ones. The ability of this complex figure to endure for more than fourteen centuries results not only from his manifold roles and their imaginative appeal, but also from significant, often irresolvable tensions or polarities [...] between beast and human (Wild Man), natural and supernatural (Wonder Child), physical and metaphysical (Poet), secular and sacred (Prophet), active and passive (Counselor), magic and science (Wizard), and male and female (Lover). Interwoven with these primary tensions are additional polarities that apply to all of Merlin's roles, such as those between madness and sanity, pagan and Christian, demonic and heavenly, mortality and immortality, and impotency and potency.[2]

In 2011, Merlin was one of eight British magical figures that were commemorated on a series of UK postage stamps issued by the Royal Mail.[60] Things named in honour of the legendary figure have included the asteroid 2598 Merlin, the metal band Merlin, and the literary magazine Merlin.

See also

- Merlin's Cave, a location under Tintagel Castle

Notes

- ^ As noted by Alan Lupack, "Merlin plays many roles in Arthurian literature, including bard, prophet, magician, advisor, and warrior. Though usually a figure who supports Arthur and his vision of Camelot, Merlin is, because of the stories in which he is said to be the son of a devil, sometimes presented as a villain."[1]

- ^ Peter H. Goodrich wrote, "According to authorial and cultural interests, [Merlin] assumes seven primary roles: Wild Man, Wonder Child, Prophet, Poet, Counselor, Wizard, and Lover. Most literature about the mage is selective, emphasizing and elaborating one or more of these features and de-emphasizing or even eliminating others. Moreover, Merlin was not always all of these things. Instead, his figure developed by gradually accreting varied capabilities to itself, each one suggesting further capabilities and roles."[2]

- ^ The stones, in actuality, came from the Preseli Hills in south-west Wales.[18] Unlike in the later accounts since Layamon's Brut,[19] Geoffrey's Merlin actually does not use magic in this episode.

- ^ One version of the Prose Tristan makes him by the same token a "half-brother" of the monster known as the Questing Beast.[25] Merlin's mother is usually unnamed, but Paolino Pieri's Italian rewrite La Storia di Merlino calls her Marinaia.

- ^ Blaise also figures within the text as its supposedly "actual" author, decades later writing down Merlin's own words in a third-person narration.

- ^ In an example of Merlin's interventions, the Vulgate version has him conjure a magical mist that causes the forces of Arthur's enemy King Amant to clash with the Saxon army at Carmelide. Merlin's part in the wars is depicted in more detail in the recently-found Bristol Merlin fragment.[29]

- ^ Merlin appears as a woodcutter with an axe about his neck, big shoes, a torn coat, bristly hair, and a large beard. He is later found in the forest of Northumberland by a follower of Uther disguised as an ugly man and tending a great herd of beasts. He then appears first as a handsome man and then as a beautiful boy. Years later, he approaches Arthur disguised as a peasant wearing leather boots, a wool coat, a hood, and a belt of knotted sheepskin. He is described as tall, black and bristly, and as seeming cruel and fierce. Finally, he appears as an old man with a long beard, short and hunchbacked, in an old torn woolen coat, who carries a club and drives a multitude of beasts before him.[30]

- ^ In the Livre d'Artus, for instance, Merlin enters Rome in the form of a huge stag with a white fore-foot. He bursts into the presence of Julius Caesar (here Arthur's contemporary) and tells the emperor that only the wild man of the woods can interpret the dream that has been troubling him. Later, he returns in the form of a black, shaggy man, barefoot, with a torn coat. In another episode, he decides to do something that will be spoken of forever. Going into the forest of Brocéliande, he transforms himself into a herdsman carrying a club and wearing a wolf-skin and leggings. He is large, bent, black, lean, hairy and old, and his ears hang down to his waist. His head is as big as a buffalo's, his hair is down to his waist, he has a hump on his back, his feet and hands are backwards, he is hideous, and is over 18 feet tall. By his arts, he calls a herd of deer to come and graze around him.[30]

- ^ The Italian Tristan tradition identifies the Wise Damsel (Savia Donzella / Savia Damigella) as the usually unnamed fairy enchantress who abducted Tristan's father Meliodas to be her lover. In some versions, including the Tavola Ritonda, Merlin (Merlino) first appears as a knight to foretell the death of Meliodas' wife Eliabella, who will search for her husband without success while pregnant with Tristan. He then gathers and leads a group of the knights of the realm Leonis to the Wise Damsel's magically hidden and otherwise unnaccessible tower or castle deep in the wilderness of the forest Dirlantes (the same Darnantes that Merlin sometimes meets his end) so they can kill her, which Merlin explicitly orders them to do, and free Meliodas. Years later, Tristan and Iseult will take refuge in her now abandoned but still enchanted castle while hiding from King Mark.

- ^ As summarized by Anne Berthelot, depending on the version of the narrative, "it may be that a lustful Merlin seduces an (almost) innocent Morgue [Morgan], thus pushing her to her déchéance (downfall). Or Morgue may appear as an ambitious and unscrupulous bitch ready to seduce an old tottering Merlin in order to gain the wisdom he alone can dispense."[48]

- ^ Merlin also otherwise protects Morgan in several other texts, including warning her of Arthur's wrath in Malory's telling of the plot of Accolon.

- ^ In the Post-Vulgate Suite, Viviane (Niviene) is introduced as a young teenage princess. She is about to depart from Arthur's court following her initial episode but, with some encouragement from Merlin, Arthur asks her to stay in his castle with the queen. During her stay, Merlin falls in love with her and desires her. Viviane, frightened that Merlin might take advantage of her with his spells, swears that she will never love him unless he swears to teach her all of his magic. Merlin consents, unaware that throughout the course of her lessons, Viviane will use Merlin's own powers against him, forcing him to do her bidding. When Viviane finally goes back to her country, Merlin escorts her. However, along the way, Merlin receives a vision that Arthur is in need of assistance. Viviane and Merlin rush back to Arthur's castle, but have to stop for the night in a stone chamber once inhabited by two lovers (a king's son Anasteu and a peasant woman in their forbidden affair). Merlin relates that when the lovers died, they were placed in a magic tomb within a room in the chamber. That night, while Merlin is asleep, Viviane, still disgusted with Merlin's desire for her, as well as his demonic heritage, casts a spell over him and places him in the magic tomb so that he can never escape, thus causing his slow death.

- ^ The Conte referred to in the story is an unknown, supposedly separate text that might have been just fictitious.[52] However, the Spanish Post-Vulgate manuscript known as the Baladro del sabio Merlin (The Shriek of the Sage Merlin), does describe what happened next. Merlin informs Bagdemagus that only Tristan could have opened the iron door sealing the cave in which Merlin is trapped in, but Tristan is by that time still just a baby. Merlin than gives the story's eponymous great cry in a demonic voice, calling for his father to come and take him, and dies amidst a terrific supernatural event.[53]

- ^ In the Italian romance Tavola Ritonda, a fairy enchantress named Escorducarla, the mother of the evil Elergia, falls in love with Merlin and plans to trap him for herself in her purpose-built Palace of Great Desire, but Merlin foils this plot and banishes her to Avalon. Conversely, Gaucher de Dourdan's continuation of Perceval, the Story of the Grail has Merlin magically abducting a maiden who did not want to love him and then building a house for them to live in together.[56]

- ^ Merlin is credited with predicting this: "Today I will perish, overwhelmed by stones and cudgels. / Today by body will be pierced through by a sharp stake / of wood, and so my life will expire. / Today I shall end my present life engulfed in the waves."[9]: 67

References

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions about the Arthurian Legends | Robbins Library Digital Projects". d.lib.rochester.edu. Retrieved 2019-06-27.

- ^ a b Goodrich, Peter H. (June 2004). Merlin: A Casebook. ISBN 9781135583408.

- ^ Lloyd-Morgan, Ceridwen. "Narratives and Non-Narrtives: Aspects of Welsh Arthurian Tradition." Arthurian Literature. 21. (2004): 115–136.

- ^ Katharine Mary Briggs (1976). An Encyclopedia of Fairies, Hobgoblins, Brownies, Boogies, and Other Supernatural Creatures, p.440. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 0-394-73467-X

- ^ a b c Geoffrey of Monmouth (1977). Lewis Thorpe (ed.). The History of the Kings of Britain. Penguin Classics. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-044170-3.

- ^ a b "The enchanted wood". Sydney Morning Herald. March 26, 2005. Retrieved 2018-07-07.

- ^ a b "Merlin". Oxford English Dictionary. 2008. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2010.

- ^ a b Markale, J (1995). Belle N. Burke (trans) Merlin: Priest of Nature. Inner Traditions. ISBN 978-0-89281-517-3. (Originally Merlin L'Enchanteur, 1981.)

- ^ a b c d Dames, Michael. Merlin and Wales: A Magician's Landscape, 2004. Thames & Hudson Ltd. ISBN 0-500-28496-2

- ^ Collins, Little Gem (2009). Welsh Dictionary. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-728959-2.

- ^ Brian Frykenberg, "Myrddin" in: John T. Koch (ed.): Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-Clio, Santa Barbara 2006, p. 1326.

- ^ Rhys, John: Hibbert Lectures, p. 168.

- ^ a b Koch, Celtic Culture, p. 321.

- ^ Delamarre, Xavier (201), Noms de lieux celtiques de l'Europe ancienne, Errance, Paris (in French).

- ^ Ashe, Geoffrey. The Discovery of Arthur, Owl Books, 1987.

- ^ Bibliographical Bulletin of the Arthurian Society Vol. LIX (2007). P. 108, item 302.

- ^ Goodrich, Peter H. (June 2004). Merlin: A Casebook. ISBN 1135583390.

- ^ "Building Stonehenge". English Heritage.

- ^ Young, Francis (3 March 2022). Magic in Merlin's Realm: A History of Occult Politics in Britain. ISBN 9781316512401.

- ^ Marshall, Emily (1848). The Rose, or Affection's Gift. Boston Public Library. New York, N.Y. : D. Appleton & Co.

- ^ Tolstoy, Nikolai (1985). The Quest for Merlin. Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 0-241-11356-3.

- ^ Curley, Michael, Geoffrey of Monmouth, Cengage Gale, 1994, p. 115.

- ^ Gough-Cooper, Henry (2012). "Annales Cambriae, from Saint Patrick to AD 682: Texts A, B & C in Parallel Archived 2013-05-15 at the Wayback Machine". The Heroic Age, Issue 15 (October 2012).

- ^ Bromwich, Rachel (November 15, 2014). Trioedd Ynys Prydein: The Triads of the Island of Britain. University of Wales Press. ISBN 9781783161461 – via Google Books.

- ^ Berthelot, Anne (2000). "Merlin and the Ladies of the Lake". Arthuriana. 10 (1): 55–81. doi:10.1353/art.2000.0029. JSTOR 27869521. S2CID 161777117.

- ^ "The Birth of Merlin". University of Rochester Robbins Library Digital Projects. Retrieved 2019-06-19.

- ^ "Arthur and the Sword in the Stone". University of Rochester Robbins Library Digital Projects. Retrieved 2019-06-19.

- ^ "Prose Merlin". University of Rochester Robbins Library Digital Projects. Retrieved 2019-06-19.

- ^ "September: Bristol Merlin update | News and features | University of Bristol".

- ^ a b c Loomis, Roger Sherman (1927). Celtic Myth and Arthurian Romance. Columbia University Press.

- ^ Saunders, Corinne (November 9, 2018). "Lifting the Veil: Voices, Visions, and Destiny in Malory's Morte Darthur". In Archibald, Elizabeth; Leitch, Megan; Saunders, Corinne (eds.). Romance Rewritten: The Evolution of Middle English Romance. A Tribute to Helen Cooper. Wellcome Trust–Funded Monographs and Book Chapters. Boydell & Brewer. PMID 30620517 – via PubMed.

- ^ Dover, Carol (2003). A Companion to the Lancelot-Grail Cycle. DS Brewer. ISBN 978-0-85991-783-4.

- ^ Cartlidge, Neil (2012). Heroes and Anti-heroes in Medieval Romance. DS Brewer. ISBN 978-1-84384-304-7.

- ^ Lacy, Norris J. (2010). Lancelot-Grail: Lancelot, pt. I. ISBN 9781843842262.

- ^ Koch, Celtic Culture, p. 1325.

- ^ Griffin, Miranda (2011). "The Space of Transformation: Merlin Between Two Deaths". Medium Ævum. 80 (1): 85–103. doi:10.2307/43632466. JSTOR 43632466.

- ^ Le Saint Graal, ou le Joseph d'Arimathie, première branche des romans de la Table ronde. T1 / Publié d'après des textes et des documents inédits par Eugène Hucher.

- ^ Guerin, M. Victoria (1995). The Fall of Kings and Princes: Structure and Destruction in Arthurian Tragedy. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2290-2.

- ^ Lacy, Norris J. (2010). Lancelot-Grail: The Story of Merlin. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84384-234-7.

- ^ Calkin, Siobhain Bly (2013). Saracens and the Making of English Identity: The Auchinleck Manuscript. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-47171-2.

- ^ Brinkley, Roberta Florence (August 13, 2014). Arthurian Legend in the Seventeenth Century. Routledge. ISBN 9781317656890 – via Google Books.

- ^ Sauer, Michelle M. (2015-09-24). Gender in Medieval Culture. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4411-8694-2.

- ^ Consoli, Joseph P. (July 4, 2013). The Novellino or One Hundred Ancient Tales: An Edition and Translation based on the 1525 Gualteruzzi editio princeps. Routledge. ISBN 9781136511059 – via Google Books.

- ^ A Russian edition of Il Novellino with footnotes

- ^ Boyd, James (April 15, 1936). "Ulrich Füetrer's Parzival: Material and Sources". Society for the study of mediæval languages and literature – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Miller, Barbara D. (2000). "The Spanish 'Viviens' of "El baladro del sabio Merlín" and "Benjamín Jarnés's Viviana y Merlín": From Femme Fatale to Femme Vitale". Arthuriana. 10 (1): 82–93. doi:10.1353/art.2000.0035. JSTOR 27869522. S2CID 162352301.

- ^ "Arthur and Gawain - Robbins Library Digital Projects". rochester.edu. Archived from the original on 19 November 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ Berthelot, Anne (2000). "Merlin and the Ladies of the Lake". Arthuriana. 10 (1): 55–81. ISSN 1078-6279. JSTOR 27869521.

- ^ Goodrich, Merlin: A Casebook, p. 149–150.

- ^ Mangle, Josh (2018-05-01). "Echoes of Legend: Magic as the Bridge Between a Pagan Past and a Christian Future in Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte Darthur". Graduate Theses.

- ^ Lacy, Norris J. (2010). Lancelot-Grail: Lancelot, pt. I. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84384-226-2.

- ^ a b c Griffin, Miranda (2015). Transforming Tales: Rewriting Metamorphosis in Medieval French Literature. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-968698-8.

- ^ Bogdanow, Fanni (1966). The Romance of the Grail: A Study of the Structure and Genesis of a Thirteenth-century Arthurian Prose Romance. Manchester University Press. p. 54.

- ^ Larrington, Carolyne. "The Enchantress, the Knight and the Cleric: Authorial Surrogates in Arthurian Romance'".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Goodrich, Merlin: A Casebook, p. 168.

- ^ Paton, Lucy Allen (November 9, 1903). "Studies in the fairy mythology of Arthurian romance". Boston, Ginn & Co. – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Ashe, Geoffrey (2008). Merlin, the Prophet and his History. Sutton. ISBN 978-0-7509-4149-5.

- ^ "Merlin's Mount, Marlborough, Wiltshire". The Northern Antiquarian. 10 June 2010. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ a b "Merlin | Robbins Library Digital Projects". d.lib.rochester.edu. Retrieved 2019-07-04.

- ^ "Gallery: Royal Mail: Stamps from magical realms". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

Bibliography

- Goodrich, Peter H. (2004). Merlin: A Casebook. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-58340-8.

- Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0.

External links

- Merlin: Texts, Images, Basic Information, Camelot Project at the University of Rochester. Numerous texts and art concerning Merlin

- Timeless Myths: The Many Faces of Merlin

- BBC audio file of the "Merlin" episode of In Our Time

- Prose Merlin, Introduction and Text (the University of Rochester TEAMS Middle English text series) edited by John Conlea, 1998. A selection of many passages of the prose Middle English translation of the Vulgate Merlin with connecting summary. The sections from "The Birth of Merlin to "Arthur and the Sword in the Stone" cover Robert de Boron's Merlin

- Of Arthour and of Merlin translated and retold in modern English prose, the story from Edinburgh, National Library of Scotland MS Advocates 19.2.1 (the Auchinleck MS) (from the Middle English of the Early English Text Society edition: O D McCrae-Gibson, 1973, Of Arthour and of Merlin, 2 vols, EETS and Oxford University Press)

- Merlin

- Arthurian characters

- Druids

- English folklore

- Fictional astronomers

- Fictional characters who use magic

- Fictional characters with neurological or psychological disorders

- Fictional depictions of the Antichrist

- Fictional half-demons

- Fictional humanoids

- Fictional offspring of rape

- Fictional prophets

- Fictional owls

- Fictional shapeshifters

- Holy Grail

- Legendary Welsh people

- Literary archetypes by name

- Male characters in film

- Male characters in literature

- Male characters in television

- People whose existence is disputed

- Supernatural legends

- Wizards in fiction