1964 Pacific typhoon season

| 1964 Pacific typhoon season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | January 26, 1964 |

| Last system dissipated | December 31, 1964 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Sally |

| • Maximum winds | 315 km/h (195 mph) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 895 hPa (mbar) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 54 (world record high) |

| Total storms | 39 (world record high) |

| Typhoons | 26 (world record high) |

| Super typhoons | 7 (unofficial) |

| Total fatalities | ≥8,743 |

| Total damage | Unknown |

| Related articles | |

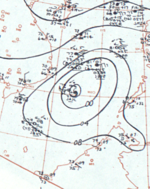

The 1964 Pacific typhoon season was the most active tropical cyclone season recorded globally, with a total of 39 tropical storms forming. It had no official bounds; it ran year-round in 1964, but most tropical cyclones tend to form in the northwestern Pacific Ocean between June and December. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the northwestern Pacific Ocean.

Tropical Storms formed in the entire west pacific basin were assigned a name by the Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Tropical depressions in this basin have the "W" suffix added to their number. Tropical depressions that enter or form in the Philippine area of responsibility are assigned a name by the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration or PAGASA. This can often result in the same storm having two names.

The 1964 Pacific typhoon season was the most active season in recorded history with 39 storms. Notable storms include Typhoon Joan, which killed 7,000 people in Vietnam; Typhoon Louise, which killed 570 people in the Philippines, Typhoons Sally and Opal, which had some of the highest winds of any cyclone ever recorded at 195 mph, Typhoons Flossie and Betty, which both struck the city of Shanghai, China, and Typhoon Ruby, which hit Hong Kong as a powerful 140 mph Category 4 storm, killing over 700 and becoming the second worst typhoon to affect Hong Kong.

Season summary

Timeline of tropical activity in 1964 Pacific typhoon season

The 1964 typhoon season was the most active Pacific typhoon season on record.[1][2] All months between and including May and November were featured an above-average number of typhoons relative to the 1959–1976 period.[3] The China Meteorological Administration (CMA), Hong Kong Observatory (HKO), Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA), and Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) each maintain tropical cyclone databases that include their respective intensity and path analyses for 1964, resulting in disparate storm counts and intensities.[4] Total tropical cyclone counts for the 1964 season include 40 from the CMA, 34 from the JMA, and 52 from the JTWC (including 7 considered "suspect cyclones").[4][5][6]: 47 There were more named storms in the northwestern Pacific in 1964 than in any other year or in any other basin.[7]

A recommendation was made at the 20th session of the United Nations Economic Commission for Asia and the Far East (now known as the UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific [ESCAP]) in March 1964 for the United Nations Secretariat and World Meteorological Organization to investigate the feasibility of a multinational program for monitoring typhoons.[8] This led to the formation of the ESCAP/WMO Typhoon Committee, which held its inaugural session in 1968.[9] Prior to the inception of the Typhoon Committee, the United States Indo-Pacific Command had designated the U.S. Fleet Weather Central in Guam as the JTWC in May 1959. The JTWC was tasked with warning U.S. government agencies on tropical cyclones in the northwestern Pacific, in addition to researching and orchestrating aircraft reconnaissance into such storms.[6]: i Boeing B-47 Stratojets were deployed from the 54th Weather Reconnaissance Squadron to carry out airborne reconnaissance.[6]: 11 The JTWC issued 730 warnings on 26 typhoons, 14 tropical storms, and 5 tropical depressions. The number of typhoons was a new record, topping the 24 set in 1962.[6]: 47 Ten of these occurred in the South China Sea, compared to the annual average of 3.2 in the five years preceding 1964.[6] The anomalous strength of tropical waves observed during the latter-half of the year may have contributed to season's high activity.[10] Ten of the year's tropical cyclones—Grace, Helen, Nancy, Pamela, Ruby, Fran, Georgia, Iris, Kate, Louise, and Opal—were first detected using meteorological satellites.[11]

The active typhoon season was also impactful.[12] More storms passed near Hong Kong in 1964 than in any prior year. The Royal Observatory Hong Kong issued tropical cyclone warning signals 42 times for ten different storms; these warnings were in effect for 570 hours. Two of these storms, Ruby and Dot, prompted the highest warning signal, signal no. 10.[13] No year prior to 1964 featured more than two typhoons affecting Hong Kong on record.[14] Ten typhoons impacted the Philippines, including Winnie (known as Dading in the Philippines),[15] Luzon's severest typhoon since 1882.[12] The effects of typhoons in 1964 led to a 3.1 percent decrease in rice output from the Philippines.[16] Six typhoons and two tropical storms struck Vietnam, including three tropical cyclones in a twelve-day period in November. The combined effects of Iris and Joan killed as many as 7,000 people and led to the worst floods in six decades.[12]

In May 1964, the western Pacific was characterized by anomalously high geopotential heights towards the northern part of the basin and low geopotential heights in the tropical regions. This configuration was favorable for tropical cyclogenesis and led to the development of typhoons Tess and Viola, the first storms of the 1964 typhoon season.[6][17] Shower activity in the tropics west of Hawaii was above average between May 10–20.[18] The first half of June marked a reversal of this pattern as a large area of low pressure became established over the mid-Pacific.[19] The average sea-level pressure for the month was below normal for most of the northern Pacific.[18] Typhoons Winnie and Alice formed in the second half of the month when the initial height patterns returned.[19] July 1964 featured more tropical cyclones than any other July on record, though this was superseded by the 1971 Pacific typhoon season.[20] A strong high pressure area south of Japan caused most storms during July to take slow and westward paths.[21]

August was another above-average month for tropical activity in the basin. Pressures across most of the western Pacific were lower than average, particularly around Okinawa where tropical cyclone activity was high during the month.[22] Between August 10–19, a progression of cyclones in the upper troposphere triggered wind perturbations closer to the ocean surface, leading to the genesis of Tropical Storm June, Typhoon Kathy, Tropical Storm Lorna, and Tropical Storm Nancy.[23] Typhoons Kathy and Marie were involved in a Fujiwhara interaction that led both storms to rotate counterclockwise around each other, ending with Marie's absorption into Kathy's circulation.[24][25] A paper published in the Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society described the resulting paths of the two storms as an "archetypal example" of the Fujiwhara interaction.[26] In September, tropical cyclone activity was high across the Northern Hemisphere in both the Atlantic and Pacific. Subtropical ridging in the Pacific was extended zonally throughout the month, resulting in strong easterly winds in the subtropical latitudes and providing conducive conditions for storm development. The extensive ridging also prevented most of September's storms from taking curved paths into the westerlies; while approximately half of September typhoons curve into the westerlies on average, only one typhoon, Wilda, took such a trajectory in 1964.[27] The strong substropical ridging continued into October, leading to similar storm paths.[28]

Systems

Typhoon Tess (Asiang)

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa)c |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 97 | 966 |

| HKO | 75 | 965 |

| JMA | — | 960 |

| JTWC | 85 | 965 |

| Category 2-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | May 12 – May 23[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 155 km/h (100 mph) (1-min); 960 hPa (mbar) |

The first tropical cyclone of 1964 developed from a segment of the polar trough. A wind circulation was first identified near Woleai by the JTWC on May 9. This initial disturbance traveled west-northwest, passing near Ulithi and Yap.[6]: 72 On May 14, it organized further into a tropical depression and took an erratic track over the next four days, including a looping course.[29][6]: 50, 74 During this process, it strengthened into a tropical storm, weakened to a tropical depression, and reattained tropical storm intensity before heading on an east-northwestward to northeastward trajectory.[29][12]: 74 On May 19, a reconnaissance flight investigating Tess observed two eyes: the first and innermost eye measured 9.7 km (6.0 mi) across while the second was asymmetrical, with axes roughly 23 and 14 km (14.3 and 8.7 mi) across.[6]: 75 Shortly after finding this feature, Tess was estimated to have attained typhoon status.[29]

Tess tracked towards the northeast after reaching typhoon intensity. Its center passed between Alamagan and Guguan on May 20 while maximum sustained winds in the typhoon were 140 km/h (87 mph).[29] Farther southeast, in Guam, the passing storm produced 52 mm (2.0 in) of rain.[30] The next day, Tess reached its peak intensity with winds of 155 km/h (96 mph) and a minimum barometric pressure of 960 hPa (mbar; 28.35 inHg).[29] A seabee stationed on the island was presumed to have drowned after being swept away by the rough seas generated by the storm; two landing crafts were also destroyed by the rough seas.[31] At noon on May 21, the center of Tess passed 160 km (99 mi) west of Marcus Island,[12]: 74 bringing squalls accompanied by heavy rain and winds of 90 km/h (56 mph).[32][33] Gusts reached 117 km/h (73 mph) and rainfall accumulations reached 94 mm (3.7 in) on the island, though there was "little damage."[17] Gradual weakening followed,[12]: 74 with winds diminishing below typhoon intensity on May 22. The system then began to curve east as it transitioned into an extratropical cyclone by May 24, and was last noted three days later.[29]

Typhoon Viola (Konsing)

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 68 | 980 |

| HKO | 65 | 980 |

| JMA | — | 980 |

| JTWC | 70 | 980 |

| Category 1-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | May 21 – May 29[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 130 km/h (80 mph) (1-min); 980 hPa (mbar) |

According to data from the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA), the progenitor to Typhoon Viola emerged in the South China Sea just east of Vietnam on May 21.[34] This system initially moved towards the north before curving sharply east. Three days later, the system organized into a tropical depression after the JTWC identified a surface wind circulation.[6]: 81 Viola reached tropical storm strength on May 25 and then curved northwest, strengthening further into a typhoon on May 27 and peaking in strength with winds of 130 km/h (81 mph).[34] These winds diminished to 110 km/h (68 mph)—just under typhoon intensity—as Viola made landfall approximately 160 km (99 mi) west of Hong Kong at 03:00 UTC on May 28.[34][12]: 74 The storm weakened over mainland China and dissipated on May 30.[34]

The Royal Observatory Hong Kong issued typhoon signal No. 8 ahead of Viola's approach, signifying gale-force conditions, a peak gust of over 140 km/h recorded in Waglan Island, the highest ever in May. Ferry services were suspended in the territory.[13]: 66, 74 Hong Kong recorded 300.6 mm (11.83 in) of rain in five days from the passing typhoon. The rainfall brought an end to an over two-year-long drought that had prompted a year-long water rationing in the territory.[35][36][37]: 72 More rain fell in roughly 24 hours than in 1964 prior to Viola's arrival.[38] The storm uprooted trees, triggered landslides, and put over 6,000 telephones out of commission.[39] Vegetable crops were badly damaged.[40] Viola generated a 0.94-meter-high (3.08 ft) storm surge at Quarry Bay and grounded four ships, including three freighters at Hong Kong.[41][42][12]: 74 Forty-one people were hospitalized by the storm and over a thousand were left homeless.[43][40] Further inland, the storm relieved drought conditions in the Chinese province of Guangdong.[42]

Typhoon Winnie (Dading)

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 87 | 955 |

| HKO | 90 | 970 |

| JMA | — | 968 |

| JTWC | 100 | 950 |

| Category 3-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | June 24 – July 4[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 185 km/h (115 mph) (1-min); 968 hPa (mbar) |

Typhoon Winnie—named Dading in the Philippines[45][15]—originated from a mid-Pacific trough, which organized into a cyclonic circulation on June 21 west-southwest of Pohnpei.[6]: 86 This initial system moved towards the west-northwest, passing near Ulithi on June 25. The next day, the disturbance developed into a tropical depression and gradually took on a more westward course. Winnie reached tropical storm strength on June 27 and then typhoon strength on June 28 as it rapidly intensified en route to southern Luzon.[44][12]: 74 The typhoon attained sustained winds of 165 km/h (103 mph) shortly before moving ashore Calabarzon on June 29;[44] its eye passed directly over Manila.[46] Winnie weakened as it moved over Luzon and restrengthened upon reaching the South China Sea, taking a west-northwesterly heading.[44][12]: 74 There, Winnie reached its peak intensity with winds of 185 km/h (115 mph) and a central pressure of 945 hPa (mbar; 27.91 inHg). At 00:00 UTC on July 2, the typhoon made landfall on Hainan southwest of Wenchang with winds of 175 km/h (109 mph). Winnie weakened to a tropical storm and traversed Hainan and the Gulf of Tonkin before making a final landfall near Haiphong, Vietnam, on July 3. Further weakening ensued as the system tracked across northern Vietnam and southwest China before dissipating on July 4.[44]

Manila experienced its most damaging typhoon since 1882. Nearly a million people were affected by the storm; according to the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), there were 56 fatalities and 163 injuries as a result of Winnie in the Philippines, with a damage toll of US$8 million.[47][48] However, the Associated Press reported 89 fatalities on July 3 while United Press International reported 120 fatalities on July 5, with property damage estimated at over $30 million.[49][50][51] The Red Cross enumerated 275 injuries.[52] Heavy rains from the combination of Winnie and the southwest monsoon flooded entire neighborhoods in Manila.[53] At least 10 people were killed by flooding rivers near Manila and in Manila Bay.[46] Approximately 500,000 people were rendered homeless in the Manila area and in the central provinces of Luzon following the razing of thousands of homes;[54][12]: 74 most of these homes were nipa huts and "makeshift dwellings". Approximately 120,000 homes were destroyed in Bataan, Bulacan, and Pampanga.[55] The loss of roofs was widespread.[53] Thousands of trees were uprooted and basic utilities were brought down by the storm;[56] Manila was without power or water for at least 36 hours.[52] In Infanta, Quezon, a maximum wind of 127 km/h (79 mph) was measured.[57] Abaca and coconut plantations in Luzon were seriously impacted. Cargo barges and freighters broke from their moorings and a Philippine Navy destroyer, the RPS Rajah Soliman, capsized while undergoing repairs.[52][46][55] Several aircraft were damaged, including 15 C-47 Skytrains at Nichols Field.[46][12]: 74 The air traffic control tower at Manila International Airport was put out of commission following wind damage.[46][58] Manila was placed under a state of emergency following Winnie, with government agencies deploying medical and rescue teams to affected areas amid widespread power outages.[52] Catholic Relief Services aided in disaster relief with funding from USAID.[59] South Vietnam delivered 450 metric tons (500 short tons) of rice to victims of the storm in the Philippines.[60] Dikes and salt fields were damaged in two districts of Nam Định, Vietnam.[61]

Typhoon Alice

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 58 | 995 |

| HKO | 55 | 985 |

| JMA | — | 1000 |

| JTWC | 65 | 990 |

| Category 1-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | June 27 – June 29[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 120 km/h (75 mph) (1-min); 1000 hPa (mbar) |

On June 26, a disturbance formed from an easterly tropical wave southeast of Guam and strengthened into a tropical depression later that day.[62][6]: 92 Tracking towards the west-northwest, Alice's intensity fluctuated in its initial stages.[62] On June 27, Alice made its closest approach to Guam, passing 95 km (59 mi) southwest of the island. A peak gust of 59 km/h (37 mph) was registered on the island, as well as 14 mm (0.55 in) of rain.[30]: 46 The JTWC assessed Alice to have briefly attained typhoon status on June 27 with sustained winds of 120 km/h (75 mph).[62] According to the agency, Alice was the smallest typhoon of 1964, with a radius of 320 km (200 mi).[6]: 47 It rapidly weakened after reaching its peak strength.[6]: 50 The storm followed 1,130 km (700 mi) behind the larger Typhoon Winnie to its west and was eventually absorbed into Winnie's circulation over the Philippine Sea on June 29.[62][12]: 75

Typhoon Betty (Edeng)

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 106 | 958 |

| HKO | 80 | 960 |

| JMA | — | 960 |

| JTWC | 110 | 958 |

| Category 3-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 2 – July 7[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 205 km/h (125 mph) (1-min); 960 hPa (mbar) |

The disturbance that led to Typhoon Betty was first detected in the Philippine Sea on July 1 by the JTWC, having developed from a segment of a polar trough within an area of conducive winds in the upper-troposphere.[6]: 96 The next day, the disturbance quickly developed into a tropical cyclone and strengthened into a typhoon by the end of July 2.[63] Reconnaissance aircraft observed an eye 75 km (47 mi) in diameter in Betty's first few hours as a typhoon.[6]: 98 The storm's winds continued to increase, and on July 3 its winds reached 185 km/h (115 mph) before the rate of intensification stalled.[63] Betty took a northwestward trajectory towards the southern Ryukyu Islands,[12]: 75 bringing its eye across southern portions of Miyakojima on July 4.[64] There, sustained winds reached 138 km/h (86 mph), punctuated by a maximum gust of 201 km/h (125 mph). The island also recorded 124 mm (4.9 in) of rain from Betty.[65]

After passing the Ryukyu Islands and entering the East China Sea, Betty continued to intensify further, with its sustained winds reaching 205 km/h (127 mph) on July 5.[63] At the time, the typhoon was located approximately 320 km (200 mi) south of Shanghai.[12]: 75 Betty's winds subsequently began to diminish precipitously while the storm curved towards the north and then north-northeast, briefly paralleling the coast of Zhejiang before entering the Yellow Sea.[63][12]: 75 Betty degenerated into a tropical storm and further into a tropical depression on July 6. It then transitioned into an extratropical cyclone on July 7 and dissipated over open waters just off the coast of northwestern South Korea.[63][6]: 96

Typhoon Cora (Huaning)

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 126 | 970 |

| HKO | 125 | 920 |

| JMA | — | 970 |

| JTWC | 140 | 967 |

| Category 5-equivalent super typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 5 – July 11[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 260 km/h (160 mph) (1-min); 970 hPa (mbar) |

Typhoon Cora developed from the interaction of a polar trough with an easterly tropical wave.[6]: 103 A wind circulation materialized from this interaction on July 4 west of Chuuk State.[6]: 104 On July 6, it organized into a tropical depression southwest of Guam,[66][12]: 75 prompting the JTWC to initiate warnings.[6]: 104 Intensification was rapid upon developing, with Cora becoming a typhoon by the end of July 6. Two days later, Cora attained sustained winds of 260 km/h (160 mph) as it approached the central Philippines on a westward heading, according to the JTWC;[12]: 75 this classified Cora as a super typhoon.[6] The eye spanned 6 mi (9.7 km) across at this juncture.[6]: 105 Two consecutive airborne reconnaissance missions into the storm estimated that winds near the surface were around 325 km/h (202 mph). However, this value was discordant with the 130 km/h (81 mph) winds occurring at flight level and a surface air pressure of 970 hPa (mbar; 28.64 inHg) estimated by the flights and by the JTWC. An analysis of the historical tropical cyclone record for the West Pacific published in the Monthly Weather Review concluded that there was "sufficient evidence" that the winds in storms like Cora were "likely overestimated."[67] The Royal Observatory Hong Kong analyzed a substantially lower pressure of 920 hPa (mbar; 27.17 inHg) at the time of Cora's peak strength.[66]

As Cora neared northern Samar and southern Luzon on July 9, its forward motion slowed and its winds unexpectedly diminished and fell below the typhoon threshold.[68][12]: 75 Storm warnings were issued in southeastern Luzon with Cora 100 km (62 mi) east of Samar, with forecasts projecting stormy conditions in the region and in other islands in the east-central Philippines.[69] However, the cyclone's winds continued to lessen before the system reached the islands.[70][71] By July 10, Cora had weakened to a tropical depression. It tracked across southeastern Luzon and dissipated in the South China Sea the next day.[66]

Typhoon Doris (Isang)

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 77 | 980 |

| HKO | 70 | 965 |

| JMA | — | 995 |

| JTWC | 80 | 974 |

| Category 1-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 11 – July 17[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 150 km/h (90 mph) (1-min); 995 hPa (mbar) |

The initial system that led to Typhoon Doris began between Pohnpei and Chuuk State on July 9.[6] Tracking towards the west-northwest, it passed near Chuuk and became a tropical depression on July 11 while 480 km (300 mi) south of Guam.[72][6][12]: 75 Doris became a tropical storm by 12:00 UTC that day as it began to track northwest across the Philippine Sea. Early on July 13, Doris strengthened into a typhoon while approximately 800 km (500 mi) east of Luzon.[72][12]: 75 The next day, Doris attained one-minute sustained winds of 150 km/h (93 mph). It weakened as it curved north towards the southern Ryukyu Islands, becoming a tropical storm on July 14 and then a tropical depression on July 15 while passing near Tarama, Okinawa. The system continued to decay as it moved north and dissipated over the Yellow Sea on July 17.[72]

Typhoon Elsie (Lusing)

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 77 | 995 |

| HKO | 90 | 945 |

| JMA | — | 1000 |

| JTWC | 100 | 992 |

| Category 3-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 14 – July 19[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 185 km/h (115 mph) (1-min); 1000 hPa (mbar) |

Elsie emerged from a detached portion of a polar trough on July 13 near the Northern Mariana Islands; this developed into a tropical depression later that day.[73][6]: 115 The depression intensified into a tropical storm two days later, with its course concurrently curving west. Elsie intensified on approach to the Philippines, with the JTWC assessing it as a typhoon on July 16.[73] At 04:00 UTC the next day, an aerial reconnaissance mission into Elsie estimated that the storm's winds reached 185 km/h (115 mph).[6]: 117 The JTWC determined that this was Elsie's peak intensity.[6]: 115 Storm warnings were posted for Luzon on July 17 ahead of the storm's approach.[74] The typhoon then weakened rapidly from this peak; upon its landfall on the eastern coast of southern Luzon on July 17,[12]: 75 it was a 140-km/h (85 mph) typhoon, with its intensity lowering to tropical storm stauts over the island shortly afterwards.[73][6]: 50 Rainy squalls associated with Elsie caused extensive flooding in Manila and the northern Philippines, inundating buildings and streets.[75][76] Elsie continued to weaken after emerging into the South China Sea and dissipated on July 19.[73]

Typhoon Flossie (Nitang)

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 77 | 980 |

| HKO | 70 | 965 |

| JMA | — | 980 |

| JTWC | 80 | 974 |

| Category 1-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 24 – July 29[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 150 km/h (90 mph) (1-min); 980 hPa (mbar) |

The initial vortex that became Typhoon Flossie was detected east of Luzon on July 24,[6]: 121 embedded within an area of low pressure.[12] It moved towards the northeast across the Philippine Sea and became a tropical depression on July 25.[77][6]: 121 It became a tropical storm the next day as it curved northwest, passing south of Okinawa and intensifying into a typhoon shortly afterwards in the East China Sea. On July 28, Flossie continued to curve towards the north, passing just offshore the eastern coast of China near Shanghai. Flossie reached its peak strength during this time with winds of 150 km/h (93 mph). After traversing the Yellow Sea, Flossie made landfall on North Korea along the coast of the Korean Bay on July 29 with winds estimated at 100 km/h (62 mph). The storm weakened over land, passing over southeastern Manchuria and Siberia, and was last monitored over Sakhalin.[77][12]

Flossie's peak winds were approximately 75 km/h (47 mph) at the time of its closest passage to Okinawa, as measured by both aircraft reconnaissance and the USS President Roosevelt.[77][12]: 75 The U.S. Navy ships George Clymer and the El Dorado collided at Okinawa amid Flossie's gale-force winds;[78][12]: 75 one ship sustained a hole 0.9 m (3.0 ft) wide in her bow.[79] A third ship, the USS Weiss, ran aground at Buckner Bay after the storm separated the ship from its anchorage.[80][12]: 75 The USS Tawasa was dispatched to tow the stricken Weiss out to sea, but was itself grounded on an unforeseen pinnacle upon dislodging the Weiss.[81] Flossie destroyed 15 fishing boats and drowned 12 fishermen off the western coast of the Korean peninsula; another 27 fishermen was listed as missing.[82][83] At least 17 people overall were killed by the typhoon on the peninsula.[84]

Tropical Storm Grace (Osang-Paring)

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 48 | 998 |

| HKO | 45 | 1000 |

| JMA | — | 998 |

| JTWC | 50 | 994 |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 25 – August 4[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 95 km/h (60 mph) (1-min); 998 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Storm Grace was the first of ten tropical cyclones in the 1964 typhoon season discovered by meteorological satellites.[11] Upon its detection, it was 1,000 km (620 mi) southeast of Okinawa.[86] The precursor disturbance formed on July 25 and took an initially northward track, veering west and organizing into a tropical depression on July 26. Grace became a tropical storm the following day and ultimately attained maximum sustained winds of 95 km/h (59 mph) on July 28 while situated in the central Philippine Sea. The storm then began to take an erratic path that continued for the next three days.[85] During this period, the JTWC considered Grace to have temporarily lost its tropical cyclone status,[6]: 61 becoming an indescript collection of squalls.[22] After taking a northward heading, Grace redeveloped on August 3 and tracked across the Satsunan Islands. On August 4, the storm weakened and dissipated west of Kyushu.[85]

Typhoon Helen

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 145 | 935 |

| HKO | 115 | 930 |

| JMA | — | 930 |

| JTWC | 130 | 931 |

| Category 4-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 27 – August 4[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 240 km/h (150 mph) (1-min); 930 hPa (mbar) |

Helen began within a region of sparse weather observations east of the Northern Mariana Islands on July 27, starting with a northward track that curved towards the northwest.[87][12]: 75 Helen became a tropical storm by 18:00 UTC on July 27 and then reached typhoon strength by 06:00 UTC on July 29. The JTWC assessed Helen to have reached its peak intensity on July 30 with sustained winds of 240 km/h (150 mph) and a central pressure of 930 hPa (27.46 inHg).[87] The typhoon passed within 160 km (99 mi) of Iwo Jima around noon that day.[12]: 75 An aircraft reconnaissance mission observed two concentric eyewalls spanning 11 and 80 km (6.8 and 49.7 mi) across.[6]: 129 Helen moved across the northern Ryukyu Islands and southern Kyushu on August 1 and entered the Yellow Sea as a weakened typhoon.[87][12]: 75 The nexr day, the center of Helen moved over Jeju-do with winds of 150 km/h (93 mph) as estimated by the JTWC.[87] Winds of 135 mph (217 km/h) were experienced on the island.[88] On August 3, Helen weakened to a tropical storm and made landfall near Dalian in Liaoning. The system curved towards the north and east before dissipating in the Sea of Okhotsk on August 5.[87]

Winds near the center of Helen were approximately 185 km/h (115 mph) as it crossed the northern Ryukyu Islands and Kyushu.[12] High waves and strong winds impacted southern Kyushu across the prefectures of Kagoshima and Miyazaki, unroofing homes and flooding nearly 200 homes.[89] In the city of Kagoshima, 16 homes were razed and 36 others were damaged.[90] Regional disruptions to power, train, and ferry service resulted from the storm's passage.[91] One death and 16 injuries were reported in the two prefectures.[92] An F1 tornado associated with the typhoon occurred south of Takanabe, Miyazaki, without causing casualties.[93][94] Rough surf from Helen reached the Tokyo area, drowning 13 people.[95][91] Helen killed at least nine people in South Korea;[96] 3 drowned and 15 others were missing following the sinking of a fishing boat off the southern coast.[97]

Typhoon Ida (Seniang)

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 165 | 925 |

| HKO | 120 | 930 |

| JMA | — | 925 |

| JTWC | 135 | 927 |

| Category 4-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 2 – August 12[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 250 km/h (155 mph) (1-min); 925 hPa (mbar) |

The origins of Typhoon Ida were associated with the interaction between a polar trough and a tropical wave, which resulted in the development of a tropical disturbance south of Chuuk State on August 1.[6]: 134 The disturbance became a tropical depression roughly (300 mi) southeast of Guam on August 2 and strengthened into a tropical storm later that day. Tracking towards the west-northwest, Ida reached typhoon intensity on August 4.[12] According to the JTWC, Ida reached its peak intensity with maximum winds of 250 km/h (160 mph) and a central pressure of 925 hPa (mbar; 27.31 inHg).[98] Between August 6–7, Ida moved across northern Luzon with these winds. The storm weakened over the island but restrengthened over the South China Sea on approach to Hong Kong. The center of the storm passed 65 km (40 mi) southwest of Hong Kong and made its final landfall on Guangdong Province China on August 8 as a typhoon with winds of 150 km/h (93 mph) as estimated by Royal Observatory Hong Kong. As it tracked farther inland, Ida weakened and later dissipated on August 12.[98][12]

Eleven deaths in Luzon were attributed to Ida according to data from the Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance, in addition to flooding and crop damage throughout the island.[12][99] Newswires reported disparate death tolls, with the Associated Press reporting 14 fatalities, the Philippine News Service reporting 23, and United Press International reporting 79.[100][101] The damage toll was around US$25 million.[102] Several fishermen also went missing during the storm;[103] 31 went missing after the presumed sinking of ship off the coast of southeastern Luzon.[101] Most communications were disrupted across northern Luzon.[104] U.S. Navy ships stationed at U.S. Naval Base Subic Bay were evacuated into the South China Sea prior to the storm's arrival and people in low-lying fishing villages left for higher ground.[105][104] A 3,541-short-ton (3,212-metric-ton) freighter sustained damage to its bilge upon being grounded near Aparri.[12] Streets in Manila were flooded to waist-height from heavy rains and hgh waves.[104][106] Two people drowned after their ship sink off Kaohsiung, Taiwan, while four people went missing after their fishing boat sank offshore Taiwan.[107]

In Hong Kong, the Royal Observatory advised ships to seek shelter in port and issued typhoon signal no. 9 at the height of the storm.[108][109] Approximately 11,000 people were evacuated from low-lying areas.[110] Gusts of 220 km/h (140 mph) reached the Crown colony, flattening over 200 homes; three people were killed and six were injured by flying debris.[12][111] Signboards and trees were also brought down by the typhoon's winds.[112] At Quarry Bay, Ida produced a storm surge of 1.31 m (4.3 ft).[41] An 11,360-ton freighter ran aground at Victoria Harbour, where two people drowned.[12][111] The Royal Observatory documented rainfall rates as high as 230 mm (9.1 in) per hour from Ida.[113] Four people were killed after a mudslide pushed into a refugee camp and razed three houses Kwun Tong, with the 20,000 m3 (710,000 cu ft) surge of mud placing areas under 7.5 m (25 ft) of debris.[110][114] Over 100 refugees were injured and 5,000 were left homeless by the mudslide.[35][110] Another seven people were killed in Korea following rains associated with Ida.[110] At least 4,000 others were rendered homeless by the resultant flooding.[100]

Tropical Storm June (Toyang)

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 38 | 998 |

| HKO | 38 | 998 |

| JMA | — | 998 |

| JTWC | 40 | 991 |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 9 – August 17[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 km/h (45 mph) (1-min); 998 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Storm June began south of Guam as a disturbance on August 9. Traveling west-northwest, it became a tropical depression by the time aircraft reconnaissance first reached the system on August 10.[115][22] Later that day, June attained a tropical storm and reached its peak intensity with winds of 75 km/h (47 mph). The storm held this intensity for a day before weakening as it neared Luzon contrary to forecasts projecting June to become a typhoon.[115][116] The JTWC issued their last warning on the system on August 11 and considered the system to have dissipated two days later when it was north of Luzon and east of Batan Island.[22][115][6]: 63 However, data from the CMA and JMA indicates that June persisted as a tropical depression into the South China Sea and took a looping course near Hainan and the Leizhou Peninsula. It then turned northeast and dissipated near the Taiwan Strait on August 18.[115]

Typhoon Kathy (Welpring)

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 126 | 948 |

| HKO | 100 | 950 |

| JMA | — | 948 |

| JTWC | 115 | 945 |

| Category 4-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 10 – August 25[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 215 km/h (130 mph) (1-min); 948 hPa (mbar) |

According to the JTWC, Kathy was both the largest and longest-lived typhoon in 1964, with the agency issuing warnings for 13.5 days and the storm's circulation reaching a diameter of 1,575 km (979 mi).[6]: 59 The interaction of a polar trough and easterly wave led to the genesis of a vortex southeast of Japan by August 11.[6]: 141 This system developed into a tropical storm the next day east of Iwo Jima based on ship observations.[117][12]: 76 Maintaining a west-northwestward heading, Kathy reached typhoon strength on August 13,[117] passing well south of Tokyo on approach towards the Ryukyu Islands.[118][119] The typhoon's winds peaked at 165 km/h (103 mph) on August 14 before tapering as the storm curved towards the west-southwest.[117][12]: 76 For the next four days, Kathy and nearby Typhoon Marie began a Fujiwhara interaction, causing both storms to rotate around one another, ending when Marie was absorbed into Kathy's circulation.[6]: 50 Between August 15–16, Kathy briefly fell to tropical storm intensity before regaining typhoon status southeast of Amami Ōshima.[117] During this period, an airplane investigating the storm identified multiple wind circulations at the center of Kathy and the storm's clouds were asymmetric.[120][6]: 146

The storm's west-southwest path brought the center across the Ryukyu Islands and near Okinawa on August 16 as Kathy began to execute a counterclockwise loop in its track. Two days later, Kathy's winds were estimated by the JTWC to be around 215 km/h (134 mph) near Minamidaitōjima. The typhoon's track made a smaller counterclockwise loop on August 20 before resuming north across the northern Ryukyu Islands. On August 23, Kathy made landfall on Kagoshima Prefecture with winds of 130 km/h (81 mph) and weakened to a tropical storm as it crossed the Seto Inland Sea and southern Honshu. It then curved to the northeast, briefly entering the Sea of Japan and crossing the Noto Peninsula before traversing northern Honshu and emerging into the northern Pacific.[117][12]: 76 On August 25, Kathy transitioned into an extratropical cyclone and continued northeast towards the Aleutian Islands before it was last in the Bering Strait on September 1.[117][12]: 76

According to the publication Climatological Data, Kathy caused at least 13 deaths and "numerous" injuries, with landslides and flooding being the principal cause of the casualties; as much as 700 mm (28 in) of rain was documented in the mountainous regions of Kyushu, though cities averaged 100 m (3,900 in) in rainfall accumulations.[121][12]: 76 United Press International reported as many as 24 fatalities and 8 missing persons associated with the typhoon,[122][123] with the Associated Press documenting 28 injuries.[124] Over 4,000 people were rendered homeless.[124] Kathy's effects flooded almost 1,700 homes and destroyed 8 others in Amami Ōshima; winds there reached 138 km/h (86 mph).[125][126] Sustained winds topped out at 126 km/h (78 mph) with a peak gust of 195 km/h (121 mph) on Yakushima.[127] As Kathy moved across southern and central Kyushu, damage was reported in Kagoshima, Kumamoto, Miyazaki, and Oita prefectures. Kathy's winds razed 44 houses and damaged 80 houses, with another 5,500 flooded by swollen rivers. Flooding broke through river embankments in 37 locations and washed away 18 bridges. Telecommunications and transportation services were disrupted with roads damaged in 400 locations.[128][123][129] There were at least 238 landslides caused by the typhoon, including one that derailed a passenger train in Oita Prefecture.[128][130] One landslide in Kagoshima killed 11 people.[131] Two thousand homes were flooded farther north in Fukushima Prefecture.[132] The extratropical remnants of Kathy brought gale-force winds over the Bering Sea.[12]: 76

Tropical Storm Lorna

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 38 | 1000 |

| HKO | 35 | 1000 |

| JMA | — | 1002 |

| JTWC | 35 | 995 |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 11 – August 14[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 km/h (40 mph) (1-min); 1002 hPa (mbar) |

Lorna began west of the Mariana Islands on August 10 and took a northeastward path throughout its duration. Its precursor disturbance developed from a trough of low pressure and became a tropical depression by August 12; the next day, Lorna became a tropical storm, prompting JTWC warnings.[133][23][6]: 63 According to the JTWC, Lorna's winds topped out at low-end tropical storm speeds, 65 km/h (40 mph), for less than a day before it began to weaken. Lorna dissipated on August 14 north of Agrihan.[133]

Typhoon Marie (Undang)

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 77 | 983 |

| HKO | 65 | 980 |

| JMA | — | 980 |

| JTWC | 70 | 976 |

| Category 1-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 12 – August 20[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 130 km/h (80 mph) (1-min); 980 hPa (mbar) |

The combination of converging low-level winds and divergence in the upper troposphere over the Philippine Sea led to the environmental conditions that resulted in the formation of Typhoon Marie. The initial disturbance formed on August 12 and tracked towards the north and then curved east, becoming a tropical depression the next day. Marie intensified into a tropical storm by August 15 and then curved north as it interacted with nearby Typhoon Kathy.[134][25][24][6]: 155 Two days later, it became a typhoon and subsequently reached its peak intensity with winds estimated by the JTWC at 130 km/h (81 mph) and a central pressure estimated by the JMA of 980 hPa (mbar; 28.94 inHg). The storm then weakened and curved towards the west; the JTWC determine Marie to have been absorbed by Typhoon Kathy approximately 240 km (150 mi) north of Okinawa on August 18.[134][12]: 76 [6]: 155 However, the CMA and JMA assessed Marie to have remained intact, continuing on a curved path towards the south and then east, bringing it around Okinawa as a tropical cyclone until its dissipation on August 20.[134]

Tropical Storm Nancy

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 29 | 1000 |

| HKO | 30 | 1000 |

| JMA | — | — |

| JTWC | 35 | 998 |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 17 – August 19[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 km/h (40 mph) (1-min); |

Nancy directly originated from a segment of a tropical upper-tropospheric trough, an atmospheric feature that was farther north than average in mid-August 1964.[136][23] Ship observations suggested that the system became a tropical depression August 17 and became a tropical storm a day later.[22] Nancy maintained low-end tropical storm intensity at peak strength before being downgraded to a tropical depression the next day approximately 480 km (300 mi) northeast of Iowa Jima, after which it dissipated.[135][22]

Tropical Storm Olga

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 48 | 994 |

| HKO | 40 | 998 |

| JMA | — | — |

| JTWC | 45 | 996 |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 21 – August 25[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 km/h (50 mph) (1-min); |

Olga remained within the Gulf of Tonkin for the entirety of its existence, taking a southward trajectory. The CMA determined that the cyclone formed on August 21, and became a tropical storm by August 24. The JTWC assessed that Olga lasted more briefly, beginning as a tropical depression on August 23 and peaking as a tropical storm the next day with one-minute sustained winds of 85 km/h (53 mph). It maintained this intensity and remained quasi-stationary over the gulf. Olga weakened to a tropical depression on August 25 and degenerated into a non-circulating cluster of thunderstorms later that day.[137][6][22]

Tropical Storm Pamela

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | — | — |

| HKO | 40 | 990 |

| JMA | — | — |

| JTWC | 50 | 1004 |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 25 – August 26[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 95 km/h (60 mph) (1-min); |

Tropical Storm Pamela was first detected on imagery from the TIROS weather satellites on August 25. At the time, it was located southeast of Wake Island.[22][11] It began as a tropical depression and became a tropical storm at 06:00 UTC on August 25, with its maximum winds increasing until reaching 95 km/h (59 mph). Pamela moved towards the west-northwest and subsequently weakened; on August 26, the system weakened to a tropical depression and dissipated after a center of circulation could not be identified by aircraft reconnaissance.[22][138]

Typhoon Ruby (Yoning)

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 87 | 960 |

| HKO | 105 | 960 |

| JMA | — | 972 |

| JTWC | 120 | 963 |

| Category 4-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 1 – September 6[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 220 km/h (140 mph) (1-min); 972 hPa (mbar) |

The tropical disturbance that organized into Ruby arose from a tropical wave west of Saipan on August 29.[6] It became a tropical storm over the central Philippine Sea on September 1 and took a slightly south of west heading, strengthening into a typhoon on September 2 and passing over the Babuyan Islands of the Philippines the following day; one-minute sustained winds at the time were estimated to be 140 km/h (87 mph).[139][140] After reaching the South China Sea, Ruby turned towards the northwest and intensified further. On September 5, Ruby attained maximum one-minute sustained winds of 220 km/h (140 mph) as it made landfall near Hong Kong and Macau. The CMA and HKO estimated a central pressure of 960 hPa (mbar; 28.35 inHg) during Ruby's landfall. After moving inland, the storm weakened and dissipated over South China on September 6.[139][12][6]

Ruby was the first of two typhoons in 1964 for which the Royal Observatory in Hong Kong raised tropical cyclone signal no. 10; this warning was in effect for nearly four hours.[140][13] The fastest wind gust from Ruby in Hong Kong was clocked at 268 km/h (167 mph) at Tate's Cairn.[141] A gust of 230 km/h (140 mph) on Waglan Island was the fastest observed in the island's history.[142] The strong winds and heavy rain caused widespread damage in Hong Kong, destroying thousands of homes and damaging thousands of others.[13][143] Fifty thousand refugees from the People's Republic of China lost their shelters.[144]: 1 Numerous ships sank or ran aground at the Hong Kong Harbor.[13][144]: 2 There were 38 fatalities and 300 injuries in the Crown colony.[13] A record gust of 211 km/h (131 mph) was measured in Taipa, Macau.[145] There, more than 20 people were killed and 100 others were injured.[146] Widespread flooding and damage occurred in Guangdong Province, leading to the deaths of over 700 people; some 300 people died when a school dormitory collapsed.[147]

Typhoon Sally (Aring)

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 194 | 897 |

| HKO | 140 | 895 |

| JMA | 120 | 895 |

| JTWC | 160 | 894 |

| Category 5-equivalent super typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 3 – September 11[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 315 km/h (195 mph) (1-min); 895 hPa (mbar) |

Sally's precursor arose from a tropical wave near the Marshall Islands on September 2.[6]: 168 The disturbance became a tropical depression and later a tropical storm the next day approximately 320 km (200 mi) northeast of Chuuk State.[12]: 76 On September 4, Sally intensified into a typhoon and passed over Guam the next day with one-minute sustained winds of 155 km/h (96 mph).[30][148] On September 7, Sally reached its peak intensity over the Philippine Sea with winds of 315 km/h (196 mph) and a central pressure of 895 hPa (mbar; 26.43 inHg).[148] Based on data from the JTWC, Sally was the strongest typhoon of the 1964 season along with Typhoon Opal as measured by maximum winds, and had the lowest pressure of any storm that year.[6]: 47 Weakening commenced thereafter as the center of Sally passed north of Luzon on a west-northwestward heading on September 9.[149][148] At 15:00 UTC on September 10, Sally made landfall on China east of Hong Kong with one-minute sustained winds of 155 km/h (96 mph). The storm weakened into a tropical storm later that day and dissipated over China on September 11.[6][12][148]

Sally inflicted around $115,000 in damage in Guam, mostly to crops, after bringing gusts of 130 km/h (81 mph) to the island and unroofing homes and felling trees.[150][30] The damage remained limited to the southern half of Guam where the storm struck;[151] there were no casualties.[152] Sally produced strong winds and heavy rains to the Philippines north of Manila, causing considerable damage.[149][153][99] Over 10,000 people were evacuated out of vulnerable areas in Hong Kong as the storm was feared to strike with a severity comparable to Typhoon Ruby a week prior.[154][155][156][157] Gusts peaked at 154 km/h (96 mph) at Tate's Cairn and rainfall accumulations reached as high as 354.4 mm (13.95 in), triggering landslides that killed nine people.[158][154] However, Sally's impacts on the Crown territory were less than initially feared;[159] much of Hong Kong's vulnerable agriculture was already badly damaged during Ruby's passage.[158] The remnants of Sally led to the heaviest rainfall in the Seoul area in 22 years, producing 125–200 mm (4.9–7.9 in) of rain in the area on the morning of September 13.[12][160] The resulting floods killed at least 211 people and injured 317 others.[161] Local authorities reported the inundation of 9,152 homes and the displacement of 36,665 people;[162] total property damage amounted to $750,000.[163]

Typhoon Tilda (Basiang)

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 97 | 965 |

| HKO | 95 | 950 |

| JMA | — | 965 |

| JTWC | 110 | 952 |

| Category 3-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 12 – September 24[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 205 km/h (125 mph) (1-min); 965 hPa (mbar) |

The precursor disturbance to Tilda was identified northwest of Guam using the Automatic Picture Transmission system during the 10-day operational lifespan of the Nimbus 1 satellite.[6]: 14 The initial vortex that became Tilda formed by September 12 and organized into a tropical depression by September 13.[6]: 177 [12]: 76 Tilda's winds reached typhoon intensity on September 14. Its center passed over the Bataan Islands the same day before moving west into the South China Sea.[12]: 76 According to the JTWC, Tilda's one-minute maximum sustained winds crested at 165 km/h (103 mph) before their speeds began to decrease.[164] On September 16, the center of Tilda passed 95 km/h (60 mi) south of Hong Kong.[12]: 76 Tilda's close pass of Hong Kong prompted the hoisting of storm signals to warn ships and small craft,[165] with the Royal Observatory escalating its warnings to typhoon signal no. 3.[13] The typhoon then became stationary for nearly two days over the South China Sea with its winds concurrently falling to tropical storm intensity according to the JTWC.[12]: 76 Tilda's meandering path disrupted shipping and led to the Royal Observatory keeping storm signals active for a record 161 hours.[166]

On September 19, the JTWC determined that Tilda reintensified into a typhoon after the storm began to move west.[12]: 76 The typhoon's one-minue sustained winds were estimated by the agency at 205 km/h (127 mph) on September 20 before weakening ensued.[164] Tilda made landfall on the coast of Vietnam on September 22 roughly 95 km (59 mi) northwest of Huế, Vietnam, and 200 km (120 mi) north of where Typhoon Violet struck a week prior.[12]: 77 [167]: 76 Storm surge at Lăng Cô reached 1.7 m (5.6 ft).[168] Tilda continued inland and weakened before dissipating by September 25.[6]: 14 Rainfall from Tilda led to some of the largest flood depths and durations on record in the drainage basin of the Mekong River;[167]: 37 the longevity and spatial extent of Tilda's rains were also near world-record-levels.[167]: 77 The highest rainfall total over a three-day period was 470 mm (19 in).[167]: 136 Precipitation totals were enhanced by orographic effects on southwest-facing slopes in southwestern Laos near the Thailand border.[167]: 44 Most buildings at the U.S. Marines base in Da Nang sustained water damage and lost power for over a week.[169] At least three people went missing in Thailand following the flooding from Tilda. Water inundation reached 0.6 m (2.0 ft) in some cities and railways and highways suspended traffic.[170][171]

Typhoon Violet

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 68 | 988 |

| HKO | 60 | 975 |

| JMA | — | — |

| JTWC | 75 | 984 |

| Category 1-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 12 – September 16[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 140 km/h (85 mph) (1-min); |

The CMA determined that Violet formed in the South China Sea on September 12, while the JTWC assessed tropical cyclogenesis on the following day.[172][12]: 77 The system quickly strengthened and reached tropical storm and later typhoon intensity on September 14. Violet's one-minute sustained winds topped out at 140 km/h (87 mph) just prior to moving ashore Vietnam.[12]: 77 Violet made landfall on Vietnam on the morning of September 15.[167]: 76 It weakened quickly over land with the JTWC issuing its last advisory on the system on September 15 and the CMA considering the system to have dissipated on September 16.[172][12]: 77

The storm generated rainfall totals in excess of 190 mm (7.5 in) between September 14–17,[167]: 76 punctuated by a maximum measured value of 245 mm (9.6 in).[167]: 145 Ninety percent of homes were destroyed in Quảng Bình Province according to early reports.[12]: 77 U.S. Marine Corps helicopters were deployed to evacuate those affected by the storm in Tam Kỳ, Vietnam. Light damage was wrought to facilities associated with U.S. Marine Corps support operations in Vietnam.[169]: 159

Typhoon Wilda

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 145 | 906 |

| HKO | 130 | 905 |

| JMA | — | 895 |

| JTWC | 150 | 905 |

| Category 5-equivalent super typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 16 – September 25[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 280 km/h (175 mph) (1-min); 895 hPa (mbar) |

According to data from the JMA, Wilda began as a tropical storm east-southeast of Guam on September 16, marked by a large mass of clouds and associated rainbands.[173][174]: 141 The system tracked northwest over the Northern Mariana Islands and into the Philippine Sea two days later.[173] The JTWC recognized the storm as a tropical cyclone on September 19 when it was located roughly 370 km (230 mi) northwest of Saipan, and assessed Wilda to have strengthened into a typhoon later that day.[12]: 77 An eye emerged on Nimbus satellite imagery on September 20,[174]: 159 and on September 21, Wilda reached its peak intensity over the Philippine Sea with one-minute maximum sustained winds of 280 km/h (170 mph) as estimated by the JTWC and a minimum central pressure of 895 hPa (mbar; 26.43 inHg).[173] Based on data from the JMA, this was tied for lowest central pressure of any typhoon in 1964, along with Typhoon Sally.[175] Wilda slightly weakened following peak strength before curving northward and making landfall on Kagoshima on September 24; one-minute sustained winds three hours prior to landfall were estimated to be 185 km/h (115 mph).[173] The storm passed over Shikoku and southern Honshu before emerging into the Sea of Japan and curving northeast. Wilda made a final landfall on the western coast of northern Honshu on September 25 as a tropical storm, thereafter departing Japan and quickly moving towards the central Aleutian Islands as a powerful extratropical cyclone.[173][12]: 77 The storm was last identified on September 27.[173]

Wilda was one of the strongest typhoons to ever strike Japan as measured by atmospheric pressure, reaching Cape Sata in Kagoshima with a central pressure of 940 hPa (mbar; 27.76 inHg).[176] The typhoon caused 47 fatalities and 530 injuries in Japan. Over 70,000 homes were destroyed and nearly 45,000 were inundated by the typhoon across the country,[177] leaving thousands of people homeless.[178] The southern and eastern coasts of Kyushu, the southern coast of Shikoku, and Hyōgo Prefecture experienced the highest proportion of destroyed homes per capita.[179] At least 64 ships were sunk with another 192 damaged or lost.[180] Damage was widespread in the northern Ryukyu Islands.[12]: 77 Banana, sugar cane, and vegetable fields in Amami Ōshima were badly damaged, along with roofs and windows. Naze lost power during the storm. Wilda brought 6-meter (20-foot) waves to southern Kyushu.[181] One British freighter ran aground off Kagoshima and broke into two; all 41 crew were rescued.[182] The widespread flooding in the region overtopped dikes and disrupted air and rail traffic.[183] At Uwajima, Ehime, a peak wind gust of 259 km/h (161 mph) was observed;[179] this was the strongest wind recorded in connection with the Wilda in Japan.[184] An 8,547-ton Indonesian freighter with 53 crew ran aground and keeled over at the Port of Kobe.[185][186] Gale-force winds from Wilda reached the Tokyo area, damaging roofs at the Tokyo Olympic Village and uprooting trees two weeks before the start of the 1964 Summer Olympics.[187][188][189] A ship just south of Tokyo Bay reported winds of 76 km/h (47 mph).[12]: 77

Tropical Storm Anita

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 38 | 995 |

| HKO | 40 | 996 |

| JMA | — | 996 |

| JTWC | 50 | 992 |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 23 – September 28[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 95 km/h (60 mph) (1-min); 996 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Storm Anita formed just west of Luzon on September 23. It initially tracked towards the southwest and attained tropical storm intensity in the central South China Sea on September 25 according to data from the JTWC. Its intensity oscillated as curved west and neared central Vietnam, peaking in strength with winds of 95 km/h (59 mph) on September 26; these winds were inferred from maritime observations near the storm. The following day, Anita made landfall near Da Nang, Vietnam, and later weakened over land; the storm dissipated on September 28.[190][191]: 52

Tropical Storm Billie (Kayang)

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 58 | 994 |

| HKO | 45 | 985 |

| JMA | — | 994 |

| JTWC | 60 | 991 |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 24 – October 2[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 km/h (70 mph) (1-min); 994 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Storm Billie began southwest of Guam on September 24.[192] The JTWC detected the system based on surface observations the next day while the system was centered 480 km (300 mi) southwest of Guam. Billie reached tropical storm intensity on September 27 as it moved west. While the system may have degenerated into an open trough of low-pressure on September 28 amid strong easterly winds, it quickly reorganized and strengthened further before tracking across southern Luzon from Catanduanes to just south of Manila with winds of 85 km/h (53 mph). Bille emerged into the South China Sea thereafter, where its winds topped out at 110 km/h (68 mph). The center of the tropical storm passed south of Hainan on September 30 and made landfall on Vietnam on October 1. Billie had already begun to weaken on approach to land but diminished further once over Southeast Asia; the storm and its remnants continued tracking west into Myanmar before dissipating on October 3.[192][191]: 53

Sixteen people were killed by floods triggered by Billie's rains in Camarines Sur. The torrents destroyed homes and left 10,000 families homeless.[193] Flooding swept away a bridge along a railroad of the Philippine National Railways, causing a passenger car to derail; one person was injured. The Manila area also experienced widespread floods.[194] Property damage from the tropical storm totaled US$3 million.[193]

Typhoon Clara (Dorang)

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 77 | 975 |

| HKO | 70 | 975 |

| JMA | — | 980 |

| JTWC | 80 | 979 |

| Category 1-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 1 – October 8[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 150 km/h (90 mph) (1-min); 980 hPa (mbar) |

Clara formed southwest of Guam on October 1 from a separating portion of a trough and initially moved towards the northwest.[195][6]: 86 Weather observations near the storm at the time of its formation were sparse.[12]: 77 The JTWC assessed the system to have reached tropical storm status on October 2. Continuing to intensify, Clara curved west over the central Philippine Sea on October 3 and strengthened into a typhoon the next day according to data from the JTWC. Clara's winds topped out at 150 km/h (93 mph) as it made landfall on the coast of Aurora at Dilasac Bay on October 5.[195][12]: 77 Warnings were raised for Clara across parts of eight Filipino provinces ahead of the storm's approach.[196]

Clara weakened over Luzon but remained a typhoon upon emerging into the South China Sea, where it eventually reattained one-minute sustained winds of 150 km/h (93 mph). Tracing a path similar to Tropical Storm Billie a week prior, the center of Clara passed south of Hainan on October 7. The storm weakened within the Gulf of Tonkin and struck Vietnam north of Đồng Hới on October 8 with one-minute sustained winds estimated at 85 km/h (53 mph) by the JTWC. The cyclone weakened inland and rapidly dissipated over Thailand on October 8.[195][12]: 77

Typhoon Dot (Enang)

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 87 | 975 |

| HKO | 80 | 975 |

| JMA | — | 980 |

| JTWC | 80 | 976 |

| Category 2-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 7 – October 15[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 165 km/h (105 mph) (1-min); 980 hPa (mbar) |

Dot originated from the interaction of a trough of low-pressure and a tropical wave west of Pohnpei in early October.[197][6]: 205 Aircraft reconnaissance first encountered the system on October 6, finding a developing tropical storm 160 km (99 mi) southwest of Yap.[12]: 77 Dot traveled on a west-northwestward heading and curved gradually towards the northwest, becoming a typhoon on October 9. Dot then curved towards the west and made landfall on northern Luzon the following day with one-minute sustained winds of 130 km/h (81 mph).[197][12]: 77 The storm continued to strengthen once it emerged into the South China Sea, and reached its peak intensity with one-minute sustained winds of approximately 165 km/h (103 mph) on October 11.[197] Dot then curved slowly northward and moved ashore China just east of Hong Kong on October 13 at largely the same intensity.[198][12]: 77 The storm then quickly weakened inland, transitioning into an extratropical cyclone on October 15 and curving northeast back into the Pacific before it was last noted off Japan on October 19.[197]

Dot was the fifth typhoon in 1964 to hit Hong Kong.[12]: 77 Its proximity to the Crown colony led to the issuance of tropical cyclone signal no. 10 from the Royal Observatory and forced the suspension of public transportation and incoming flights.[198][141][199][200] The Royal Observatory recorded 331.2 mm (13.04 in) of rain and gales for eight consecutive hours.[198][201] At Tate's Cairn, a maximum wind gust of 220 km/h (140 mph) was measured.[141] Numerous rain-triggered landslides destroyed homes and blocked roads, resulting in most of the casualties associated with the typhoon.[166][202][200] The official death toll from the storm in Hong Kong enumerated 26 fatalities and 85 injuries with 10 unaccounted for,[13]: 74 though press reports at the time indicated a higher death toll.[203] Total property damage was estimated to be in the millions of U.S. dollars.[204]

Tropical Depression Ellen

| Tropical depression (JMA) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 8 – October 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 km/h (50 mph) (1-min); 998 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Depression 37W formed west of Kawalein on October 8, peaking at a 50 mph (80 km/h) tropical storm and was given the name Ellen. Ellen dissipated on October 10 near Ponape.

Tropical Storm Fran

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 48 | 996 |

| HKO | 45 | 998 |

| JMA | — | 996 |

| JTWC | 50 | 1000 |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 13 – October 21[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 95 km/h (60 mph) (1-min); 996 hPa (mbar) |

Fran began its development northwest of the Marshall Islands around October 13.[205] Aircraft reconnaissance reached the system on October 15, encountering as a westward-moving tropical storm. Fran then took a more northward heading, and only October 17 attained peak one-minute sustained winds of 95 km/h (59 mph) approximately 650 km (400 mi) west of Wake Island according to the JTWC. Thereafter, the storm began to take on extratropical characteristics, with its center of circulation enlarging and becoming irregular.[206][205] Fran continued north before curving east after October 20, eventually transitioning into an extratropical system by October 21 and dissipating on October 23 over the open Pacific.[205]

Tropical Storm Georgia (Grasing)

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 48 | 994 |

| HKO | 45 | 994 |

| JMA | — | 994 |

| JTWC | 45 | 998 |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 18 – October 24 (exited basin)[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 km/h (50 mph) (1-min); 994 hPa (mbar) |

Tropical Storm Georgia was first observed as a tropical depression 360 km (220 mi) south-southwest of Guam on October 17. The nascent cyclone did not organize further, with aircraft reconnaissance unable to locate the storm's central vortex. However, the system became more pronounced on October 20 as it tracked towards the west-northwest, and became a tropical storm on October 21 near the Philippines. At around 06:00 UTC on October 21, Georgia made landfall on Luzon at Lamon Bay and passed north of Manila; one-minute sustained winds associated with the storm at the time were around 65 km/h (40 mph). It then crossed into the South China Sea where intensification continued as the Georgia's one-minute sustained winds reached 85 km/h (53 mph). The tropical storm passed south of Hainan and made landfall on Vietnam near Vinh on October 23, after which it dissipated.[206][207]

Typhoon Hope (Hobing)

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 77 | 974 |

| HKO | 70 | 970 |

| JMA | — | 975 |

| JTWC | 75 | 973 |

| Category 1-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 24 – October 30[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 140 km/h (85 mph) (1-min); 975 hPa (mbar) |

Typhoon Hope originated around October 21 near the island of Pohnpei, tracking west at tropical depression intensity for three days.[208] On October 24, when it was west of Guam, the JTWC upgraded the system to tropical storm status based on aerial observations of the system.[208][12]: 77 Hope continued to track west before curving north on October 25 towards an eventually northeastward track. On October 27, Hope became a typhoon northwest of the Bonin Islands as it accelerated northeast.[12]: 77 This intensification was attributed to the instrusion of colder air into the typhoon's circulation, causing a surge of winds in the lower levels of the atmosphere during a relatively short timeframe.[209][6]: 21–25 Though winds as high as 240 km/h (150 mph) were estimated by aircraft reconnaissance investigating the typhoon during this period,[12]: 78 [6]: 214 Hope's one-minute sustained winds in the JTWC's tracking data peaked at 140 km/h (87 mph).[208]

The typhoon gradually weakened thereafter, but continued to produce strong winds and waves 8.2 m (27 ft) high. On October 29, the storm weakened to tropical storm strength and later transitioned into an extratropical cyclone. The extratropical cyclone intensified on approach to the central Aleutian Islands and later became part of a broader cyclonic system within the Bering Sea.[12]: 78

Tropical Storm Iris

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 58 | 988 |

| HKO | 55 | 990 |

| JMA | — | 996 |

| JTWC | 65 | 994 |

| Tropical storm (JMA) | |

| Category 1-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 31 – November 5 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 120 km/h (75 mph) (1-min); 996 hPa (mbar) |

On November 1, the JTWC began monitoring a tropical disturbance over the South China Sea, near the western Philippines. The following day, the system quickly organized as it moved in a general eastward direction. During the afternoon, the JTWC issued their first advisory on the system, immediately declaring it Tropical Storm Iris. After briefly taking a northeasterly track, Iris turned towards the southeast and reconnaissance planes recorded a developing eyewall. The following day, the a pressure of 1000 mbar (hPa) was recorded in the center of the storm; however, this reading was not taken at the storm's highest intensity.[211] On November 4, Iris intensified into a minimal typhoon, attaining winds of 120 km/h (75 mph)[212] and featured a circular 18 mi (29 km) wide eye. Several hours later, the storm made landfall in central South Vietnam at this strength. Rapid weakening took place shortly thereafter, with the storm dissipating late on November 4 over the high terrain of Vietnam.[211]

Tropical Storm Iris brought significant rainfall to parts of Vietnam, resulting in significant flooding. However, a few days after Iris moved through the country, Tropical Storm Joan worsened the situation significantly.[213]

Tropical Storm Joan

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 48 | 998 |

| HKO | 50 | 996 |

| JMA | — | 1000 |

| JTWC | 70 | 999 |

| Tropical storm (JMA) | |

| Category 1-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | November 4 – November 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 130 km/h (80 mph) (1-min); 1000 hPa (mbar) |

The deadliest storm of the 1964 season, Tropical Storm Joan brought heavy flooding that killed 7,000 people in Vietnam.[213]

Similar to the formation of Tropical Storm Iris, Tropical Storm Joan originated from a tropical disturbance over the western South China Sea on November 5. Tracking eastward, the system quickly organized and was immediately declared a tropical storm on November 6. Early the next day, a reconnaissance plane recorded a pressure of 1000 mbar (hPa), the lowest in relation to Joan; however, this was measured while the system was a minimal tropical storm. Continued development took place over the following day as a well-defined wall cloud developed within the system.[215] Joan attained typhoon intensity during the afternoon of November 8 and reached its peak intensity with winds of 130 km/h (81 mph) shortly thereafter.[216] Tropical Storm Joan made landfall in nearly the same location as Typhoon Iris in central Vietnam before rapidly weakening over land. The system eventually weakened to a tropical depression on November 9 before dissipating over Laos.[215]

Due to the rapid succession of tropical storms Iris and Joan, widespread flooding and catastrophic flooding was reported across central South Vietnam. Roughly 90% of structures in three provinces were damaged by the storms and nearly one million were estimated to have been left homeless. Military operations during the Vietnam War were suspended by the typhoons.

Typhoon Kate

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 68 | 988 |

| HKO | 70 | 985 |

| JMA | — | 990 |

| JTWC | 80 | 986 |

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 1-equivalent typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | November 10 – November 17 (exited basin) |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 150 km/h (90 mph) (1-min); 990 hPa (mbar) |

A tropical wave was spotted off South Vietnam on November 12. The wave became Tropical Depression 45W on the 13th. The depression quickly strengthened into Tropical Storm Kate the same day. Kate made a curve to the west as a 60 mph (97 km/h) tropical storm. Kate strengthened into a typhoon on the 15th and a peak at 90 mph (140 km/h) winds the next day. Kate made landfall over South Vietnam on the 17th, dissipating over land.

Typhoon Louise–Marge (Ining–Liling)

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 155 | 923 |

| HKO | 145 | 890 |

| JMA | — | 915 |

| JTWC | 165 | 914 |

| Typhoon (JMA) | |

| Category 5-equivalent super typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | November 14 – November 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 305 km/h (190 mph) (1-min); 915 hPa (mbar) |

Louise–Marge began as a cyclonic vortex associated with a tropical wave near Yap State on November 12.[12]: 83 [6]: 232 Two days later, the system became a tropical depression, and reached tropical storm intensity on November 15.[218] This initial tropical cyclone was named Louise by the JTWC.[6] Louise became a typhoon the next day and passed 22 km (14 mi) south of Angaur with one-minute sustained winds estimated at 185 km/h (115 mph).[219][218][12]: 78 Louise continued to intensify after passing the island, and attained its peak intensity on November 18 with one-minute sustained winds of 305 km/h (190 mph) and a central air pressure of 915 hPa (mbar; 27.09 inHg).[218] Louise was unusually close to the equator for a storm of its intensity; persisting at a strength equivalent to a Category 5 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson scale at 7.3°N, closer to the equator than any other Northern Hemisphere tropical cyclone of such intensity.[220] On November 19, Louise made landfall on Lanzua Bay in Surigao del Sur, Philippines, with winds of approximately 260 km/h (160 mph).[12]: 78 [218] Meteorological agencies disagree on the evolution of Louise after landfall, with the JTWC and JMA determining that it dissipated on November 21. The two agencies determined that a second distinct tropical cyclone east of the Philippines, named Marge by the JTWC, formed concurrently.[221][222] The CMA lists the Marge as a continuation of Louise.[218] This storm tracked across Luzon and eventually dissipated in the South China Sea by November 26.[206]

Anguar and Peleliu suffered widespread damage with the toll ranging between US$50,000–US$500,000. On Peleliu, 97 percent of structures were destroyed, while 90 percent of homes on Anguar were destroyed.[223][224] The loss of homes on the two islands displaced 178 families.[225] One person was killed and four people were injured.[223] The U.S. Weather Bureau called Louise—Marge one of the most destructive storms ever documented in the central Philippines.[12] At least 576 people were killed, though the Philippine Red Cross recorded 631 fatalities, along with 157 missing people and 376,235 people displaced by the typhoon.[12][226] Nineteen Philippine provinces were impacted by the storm.[227] Widespread destruction occurred in Surigao City, where the storm killed 312 people and caused US$12.5 million in damage.;[228][229] Several ships sank during the storm, contributing in part to the death toll.[12][230][231][232] A state of calamity was declared for Surigao del Norte,[233][234] prompting an intense relief effort amid an ongoing cholera epidemic and unrelated flooding.[231][235][236] In June 1966, the Congress of the Philippines authorized ₱3.4 million to be distributed annually through fiscal year 1969-70 for the province and its municipalities.[237]

Tropical Storm Nora (Moning)

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 48 | 997 |

| HKO | 45 | 995 |

| JMA | — | 995 |

| JTWC | 55 | 995 |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | November 26 – December 2[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 km/h (65 mph) (1-min); 995 hPa (mbar) |

Nora began within the Sulu Sea near the Cagayan Islands sometime around November 26–27, and became a tropical storm shortly after it was first detected.[238][206] The storm tracked towards the northeast and reached its peak strength on November 27 with one-minute sustained winds estimated by the JTWC at 100 km/h (62 mph). Nora then curved northwest before moving ashore Mindoro in the Philippines on November 28.[238] The storm then weakened to a tropical depression and strengthened no further, though data from tracking agencies disagree on Nora's demise, with the HKO and JTWC analyzing the storm to have dissipated in the direction of the South China Sea while the CMA and JMA indicating that the system continued northeast across the Philippines before dissipating over the Philippine Sea.[238] Rough waters kicked up by the storm led to the sinking of a cargo ship near Zamboanga City, causing the presumed drownings of 18 people; another 37 crewmembers were rescued.[239]

Typhoon Opal (Naning)

| Agency | Wind (kt)[a] |

Pressure (hPa) |

|---|---|---|

| CMA | 165 | 905 |

| HKO | 150 | 905 |

| JMA | — | 900 |

| JTWC | 170 | 903 |

| Category 5-equivalent super typhoon (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | December 9 – December 16[b] |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 315 km/h (195 mph) (1-min); 900 hPa (mbar) |