Indiana Glass Company

| Company type | Private company |

|---|---|

| Industry | Glassware |

| Founded | 1907 in Dunkirk, Indiana |

| Founder | Frank Merry |

| Defunct | 2002 |

| Headquarters | |

Key people | Frank W. Merry, Charles L. Gaunt |

| Products | pressed and blown glassware including lamp fonts, lamps and tableware |

Number of employees | 1,300+ (1979) |

Indiana Glass Company was an American company that manufactured pressed, blown and hand-molded glassware and tableware for almost 100 years. Predecessors to the company began operations in Dunkirk, Indiana, in 1896 and 1904, when East Central Indiana experienced the Indiana gas boom. The company started in 1907, when a group of investors led by Frank W. Merry formed a company to buy the Dunkirk glass plant that belonged to the bankrupt National Glass Company. National Glass was a trust for glass tableware that originally owned 19 glass factories including the plant in Dunkirk. National Glass went bankrupt in 1907, and its assets were sold in late 1908.

Indiana Glass Company mostly made tableware, lamps, and vases although it had additional products. Collectors consider the company a manufacturer of Depression glass, Goofus glass, and Carnival glass. One well known customer was the A&W drive-in chain that featured mugs of A&W Root Beer, and Indiana Glass was the original manufacturer of root beer mugs for that company. Another major customer was Kmart.

During 1957, Lancaster Lens Company acquired a controlling interest in Indiana Glass. Lancaster Lens Company was renamed Lancaster Glass Company, but Indiana Glass continued to be a separate entity. By the 1960s, a reorganization had Indiana Glass Company as a subsidiary of Lancaster Colony Corporation. Indiana Glass had a resurgence in sales during the 1970s, and began marketing some of its tableware for the home through Lancaster Colony's Tiara Exclusives. Indiana Glass continued operating in Dunkirk until November 2002, when the plant was closed. Although a glass plant owned by Lancaster Colony continued operating in Oklahoma under the name Indiana Glass Company, that plant was part of a sale to another glass company in late 2007.

Background

During the late 1880s, the discovery of natural gas started an economic boom period in East Central Indiana. Gas was first found in Delaware County's town of Eaton and adjacent Jay County's city of Portland[1][2] Manufacturers were lured to the region to take advantage of the low cost fuel. Jay County, a rural county in East Central Indiana, had only 210 people working in manufacturing in 1880.[3] By 1900, the county had over 1,423 people employed at manufacturing plants that were mostly glass factories.[Note 1] East Central Indiana became the state's major manufacturing center.[6]

Beatty-Brady Glass Company

In 1895, the Pennsylvania Railroad built a large structure along its railing in Dunkirk, Indiana, close to the southeast corner of Blackford County but inside Jay County.[Note 2] The building was intended to be used for railroad freight car repair, but never used. In 1896, the building was sold to George Beatty and James Brady, who started the Beatty-Brady Glass Company.[9] By 1900, this glass plant employed 225 people, and their products were tableware.[4]

During 1888 through 1890, most glass factories in the United States had financial difficulty.[10] The United States had six economic contractions between 1880 and 1900.[11] Deflation was a problem, and the term depression has been used to describe that economic time instead of simply recession. A banking crisis occurred in 1893.[12] In addition to the difficult economic times, the Beatty-Brady Glass Company had more problems. During March 1899, George Beatty was arrested in Portland, Indiana, on six different complaints. All complaints were related to anti-union activity, and the action was said to begin "a big fight between organized and nonunion labor, and will be watched with interest all over the country..."[13] Shortly afterwards, the matter was forwarded directly to Indiana's Supreme Court.[14]

National Glass Company

In November 1899, the Beatty-Brady Glass Company was sold to the National Glass Company, a glass tableware trust that started as 11 glass companies and quickly became 19 with more added later.[15] The National Glass Company factories were unionized, and their Dunkirk plant (Beatty-Brady Glass Company) became unionized January 1, 1900.[16] The National Glass Company had its own difficulties, and was in financial trouble by 1903.[10] Although it began with numerous factories, three had been dismantled, three were destroyed by fire (and not rebuilt), and some factories withdrew from the trust. By the end of 1904, all remaining plants were idle.[10]

On January 22, 1904, National Glass announced that it would shrink its workforce and try a new way of operating—leasing plants to others. Among the plants leased was the Dunkirk plant (the Beatty-Brady plant), and it was leased by Frank W. Merry.[17] The changes were made because the conglomerate had financial difficulties, and it sold or closed several of its glass plants to raise capital.[15] The Dunkirk lease was announced in Indianapolis as "a new organization...will now operate the Beatty-Brady glass factory heretofore controlled by the National Glass Company." The new company was named Indiana Glass Company, and was said to have capital stock of $125,000. ($125,000 in 1904 is equivalent to $4,238,889 in 2023.) Merry was president.[18] On February 10, the 250 men employed at the Dunkirk plant went on strike over issues with National Glass Company.[19] The issues between the National Glass Company and union employees were settled in two weeks, and work resumed.[20]

Beginning

Sources do not always agree on the start date for Dunkirk's Indiana Glass Company. An unrelated Indiana Glass Company existed from 1892 to 1896 in Indiana, Pennsylvania.[21] An Indiana Glass Works was inspected in Dunkirk in 1901, but its product was listed as bottles—and the Beatty-Brady Glass Company, a maker of tableware, was also inspected.[22] At the beginning of 1903, Frank W. Merry was sent by National Glass Company to Dunkirk to run the Beatty-Brady plant. Merry "helped promote the organization of the Indiana Glass Company" in Dunkirk in 1904, and he was elected president of the company.[23] The new company was announced in January 1904 when Merry leased the Dunkirk glass works owned by the National Glass Company.[18] The Indiana Department of Inspection listed Indiana Glass Company as having 256 employees in 1904, and its products were "pressed and blown glass". There was no Beatty-Brady Glass Company or Indiana Glass Works listed.[24] However, 1904 is not considered the start date for Indiana Glass, as most sources list 1907 as the start date for the company.[25][Note 3]

In 1907, National Glass Company defaulted on the interest payments for its bonds, and a bank brought suit for the foreclosure of mortgages that were used as security. National Glass went into receivership during December 1907.[29] During the year, Frank Merry and associates formed a company to buy the Dunkirk glass plant. The assets of National Glass were sold at auction during November 1908.[30] The purchase of the Dunkirk plant was final in 1909, and Frank Merry continued as president.[Note 4] The major stockholders were Frank Merry, Henry J. Batsch, Harold H. Phillips, Charles W. Smalley, Rathburn Fuller, and James E. Merry.[9] Management from this time until 1915 included James Merry as vice president, Phillips as secretary and treasurer, and Batsch as factory manager.[31] In 1915, Smalley replaced James Merry as vice president. In 1916, Charles L. Gaunt replaced Phillips as secretary and treasurer.[31] The board of directors as of 1921 consisted of Frank Merry, Smalley, Gaunt, Batsch, and Fuller.[32]

Early operations

Natural gas was the original fuel used by glass factories in the Dunkirk area to heat their furnaces. However, this fuel, which is desirable for glassmaking because it can heat evenly, became depleted in the region by 1905. Indiana Glass used coal from West Virginia and Kentucky to make coal gas to use as their fuel for glassmaking. Dunkirk has a railroad line that crosses the town providing a transportation resource for coal and raw materials. Sand from Illinois, soda ash from Detroit mills, and lime from northern Ohio were major raw materials brought to Dunkirk for glass making.[33]

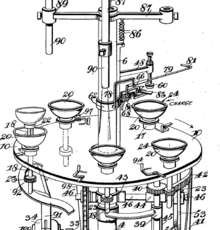

A trade magazine noted in 1916 that Indiana Glass had started "tank No. 3, which places this plant to operating at capacity."[34] In March, a Daubenspeck automatic tumbler machine was placed on tank number 3.[35] This machine would take precise amounts of molten glass and feed it into the molds for products such as tumblers. It could produce products at a faster rate, and the product would have consistent dimensions.[36][Note 5] Later in the year, it also noted that the company was again operating at full capacity and had many large orders for tumblers and table ware.[39]

By the early 1920s, the plant employed about 550 people when operating at capacity, and could produce three carloads per day of glass products.[40] The company was described in 1921 as a producer of "pressed table glassware and lamps", and "cold color and fixed decorated glassware".[41] It had sample rooms for its products in major cities such as New York, Philadelphia, Boston, Baltimore, Chicago, St. Louis, St. Paul, and San Francisco.[42] A customer of the company's barware products that became well known was the chain of A&W Root Beer stands. Indiana Glass was a long time producer of glass mugs used to serve A&W Root Beer.[43] The company's tableware was pressed in molds in machines, while vases and lamps were produced by glassblowers.[40] In 1931, Frank Merry died and Charles L. Gaunt became company president.[44]

At the start of World War II, glass plants began making less glassware for the home and more for warfare such as lenses for aircraft, trucks, and naval vessels. Tableware production resumed in the 1950s, but demand was down.[45] In 1953, Indiana Glass president Charles L. Gaunt announced that his company acquired a controlling interest in the Sneath Glass Company, which had been closed by a strike. The acquisition enabled the company to use Sneath's recipe for heat resistant glass—bolstering their large assortment of glassware products. At the time, Indiana Glass was a leader in barware, stemware, decorative crystal tableware, and novelties.[27]

Making molded glassware

Glass begins as a batch of ingredients (sand, soda, lime, and other ingredients) heated in a furnace.[46] The furnace heats the batch to a temperature over 3,000 °F (1,650 °C), which causes the batch to melt together and make molten glass.[47] For glass blown into a mold, a glass blower (human or machine) extracts a small gob of molten glass that is blown into, and shaped by, a mold.[48][Note 6] For machine–made pressed glass, the molten glass moves to a machine that drops a precisely measured gob of glass into a mold. The mold moves away from the site of injection, and the glass cools.[50]

Dunkirk's Benjamin F. Gift received a patent in 1916 for an improved glassware making machine that received a gob of molten glass, then moved the mold away while allowing the glass to cool, then discharged the glassware from the mold.[51] From the mold, the hot glass is placed on a lehr (a long conveyor inside an oven) where the glass is gradually cooled—a process called annealing. This gradual cooling is necessary to prevent the glass from becoming cracked or brittle.[52] At the far end of the lehr, packers remove the glass and get it ready for shipping. In 1931, Indiana Glass employee Jeddiah B. Clark received a patent for an improved process for transferring molten glass (or gobs) to glass blowing or pressing machines.[53] He also received a patent in 1936 for the design of a revolving tray for holding containers inside a refrigerator.[54]

Products

Indiana Glass Company had many glass patterns, and was a manufacturer of what collectors call Depression Glass.[28] The company was also a manufacturer of what collectors call Goofus glass, which was cheaply made glass with painted decorations. A third category of glassware associated with the company, also very low cost, is called Carnival glass.[55] The company also made barware. In 1919, Indiana Glass began making a 10 ounce beer mug. This mug was used by A&W for root beer at its A&W Root Beer stands. In the early 1920s, Indiana Glass introduced a child-sized mug that held 3.5 ounces and was used by A&W for children.[43]

Some of the more well-known Depression Glass patterns are Avocado, Indiana Custard, Pyramid, Sandwich, and Tea Room. Avocado is the name used by collectors for the Indiana Glass pattern number 601.[56] It was originally made from 1923 to 1933 in crystal, green, and pink. The pattern is sometimes called Sweet Pear because the "avocado" design actually looks more like a pear.[57] The pattern was revived, using 15 new colors plus pink and green, for the company's products sold through Tiara Exclusives in the 1970s through 1990s.[58][Note 7]

Indiana Custard is the collector name for Flower and Leaf Band ware that was made from the 1930s to the 1950s. The pattern was used for coffee sets (bowl, cup and saucer, platter, sugar, creamer) using an opaque glass of custard color with decorated bands. A milk glass version was called Orange Blossom.[60]

Pyramid is a pattern name used by collectors for the Indiana Glass pattern number 610. This pattern was made from 1926 to 1932. In 1974 and 1975, reproductions were made using black and blue glass that had not been used earlier for this pattern.[61] The black or blue reproductions were made for Tiara Exclusives and used in homes.[62] The original Pyramid products were intended for commercial use, but were also used in homes. This pattern had angular designs considered avant-garde during the late 1920s, while most pressed glass from that time featured floral patterns.[63]

The Sandwich pattern, Indiana Glass version, was made from the 1920s through the 1980s. (Anchor Hocking also had a Sandwich pattern.) For certain colors, the color of the glass for this pattern can be used to approximate the decade the glass was made.[64] Tiara Exclusives was selling the Sandwich pattern in 1980.[65]

Tea Room is another pattern intended for commercial use, but also used in homes. Like Pyramid, it had an angular design considered avant-garde for the late 1920s.[63] The pattern was marketed for use in tea rooms, ice cream parlors, and soda fountains.[66] Tea Room was made only from 1926 to 1931. However, its art deco appearance has made it popular with collectors. The Tea Room dinner sets were made in crystal, amber, green, and pink glass.[67]

Lancaster Colony Corporation

In 1957, the Lancaster Lens Corporation acquired a controlling interest in Indiana Glass. Robert K. Fox, president of Lancaster Lens, became president of both companies. George M. Morton, Vice President of Indiana Glass, became Vice President of both companies.[68] A month later Lancaster Lens changed its name to Lancaster Glass Corporation. The new name was said to "give a more accurate definition" of the company's manufacturing activities.[69] Lancaster Colony Corporation was organized in Delaware in 1961 as a holding company.[70] By 1963, Lancaster Colony subsidiaries included four non-glass companies plus Indiana Glass, Lancaster Glass, and Bischoff Glass Company.[71]

Tiara

Tiara Exclusives, a multi-level marketing company owned by Lancaster Colony, began on July 1, 1970. Glassware made by the companies owned by Lancaster Colony (including Indiana Glass), was sold via home parties—similar to the way Tupperware is marketed. Initially, Tiara was a success, providing part-time work for many homemakers. It employed 750 party-plan counselors by 1972.[72] The glassware sold through Tiara that was made by Indiana Glass was often produced using old patterns.[59]

Peak and decline

Peak years

By 1977, Indiana Glass was the fifth-ranking glassware producer in the country. It had sales of machine–made glassware of about $36 million, and employed over 1,000 people at its Dunkirk facility.[73] When Lancaster Colony tried to acquire Federal Glass Company in 1977 to merge with Indiana Glass, the Federal Trade Commission was opposed because of concern that a merger "may substantially lessen competition and tend to create a monopoly."[73] At its peak in 1979, the Dunkirk facility employed about 1,300 people. Indiana Glass also had a plant in Sapulpa, Oklahoma.[74]

Decline

Low-priced glassware imports were a problem for the domestic glassware producing industry. In 1986, Indiana Glass closed one of its Dunkirk facilities because of competition from imports. About 200 employees lost their jobs and received trade adjustment assistance and training from the federal government. Some of the increased competition was the result of the Caribbean Basin Initiative and the Israel–United States Free Trade Agreement, which caused a huge increase in glassware imports.[75] Indiana Glass was the third largest domestic producer of glassware, but became troubled financially. Near the end of the year, it employed about 600 people.[74]

Lancaster Colony Corporation, which reincorporated in Ohio effective January 2, 1992, had multiple businesses. Its Glass and Candles segment accounted for 27 percent of its net sales for the fiscal year ended June 30, 1994. Indiana Glass and Tiara were important trademarks for the company at that time.[70] Tiara was discontinued November 1998.[58] The closing of Tiara had a negative impact on sales for 1999.[76] By 2002, the Glassware and Candles segment for Lancaster Colony had declining revenue for three years in a row, and experienced some losses due to the bankruptcy filing of Kmart Corporation.[77]

Glassmaking ends

Members of the American Flint Glass Workers' Union went on strike at the Indiana Glass plant in Dunkirk on October 8, 2001.[78] At the time, the country was experiencing a small recession.[11] Negotiations for a new labor agreement were still ongoing by mid-December, and several confrontations between workers and company guards happened during the strike.[78] The strike lasted three months. Production was restarted, but did not last long. Lancaster Colony ceased production at the Dunkirk factory of Indiana Glass during November 2002. About 240 workers immediately lost their jobs.[79] The reason for the shutdown was economic—business had been down over the last three years. Lancaster Colony owned another glass plant in Sapulpa, Oklahoma, which had become part of Indiana Glass.[80] After the shutdown at the Dunkirk facility, production continued at the Sapulpa plant under the Indiana Glass name.[81]

In 2006, the activist hedge fund Barington Capital Group, L.P. began an effort to force Lancaster Colony to eliminate its glassmaking business.[82] In November 2007, Lancaster Colony sold most of its glassmaking business, Indiana Glass Company and E. O. Brody Company, to Monomoy Capital Partners LP. The two new acquisitions were merged into Monomoy's Anchor Hocking Company.[83]

Notes

Footnotes

- ^ In 1900, three communities in Jay County, Indiana, had factories inspected by the state. Dunkirk had six glass factories employing 825 people inspected.[4] Portland had 261 people employed in factories, but none were glass factories.[5] Redkey had three glass factories that employed a total of 337 people.[5]

- ^ The railroad was named Pittsburgh, Cincinnati and St. Louis Railroad at the time.[7] It was owned by the Pennsylvania Railroad.[8]

- ^ A timeline available from Dunkirk's Glass Museum says that early stationary used by Indiana Glass says that the company was established in 1907. At least four sources use 1907 as the start date. Shotwell says the company was incorporated in 1907.[25] Venable says the company was established in 1907.[26] A 1953 article in the American Flint says Indiana Glass "was established in Dunkirk in 1907".[27] The Kovels also say the company began in 1907.[28] At least one source, Hawkins, says 1908 is the establish date.[15]

- ^ Two sources say the sale was in 1908, the year of the November auction of National Glass Company properties.[25][9] However, a short biography of Frank Merry says the "plant was purchased in 1909."[23]

- ^ The automatic tumbler machine was noted by the American Flint, which spelled the tumbler machine as "Daubinspeck".[35] Samuel E. Winder (of Chicago) and Henry C. Daubenspeck (of Dunkirk) applied for a patent of a glass-molding machine in 1916, and received their patent in 1920.[36] Tank furnaces were essentially large brick pot furnaces with multiple workstations.[37] A tank furnace is more efficient than a pot furnace, but more costly to build.[38]

- ^ In the glass industry, a gob is a specific amount of molten glass needed to make the product.[49]

- ^ Tiara Exclusives marketed glassware products for the home through home parties, similar to the way Tupperware was marketed. Indiana Glass Company and Colony Glass Company were major manufacturers for Tiara Exclusives.[58] One author believes that glassware that is a reproduction from old molds, such as much of what was sold through Tiara, is not as valuable as that made in the original production run.[59]

Citations

- ^ "Indiana's Natural Gas Boom". The American Oil & Gas Historical Society. Retrieved 2018-06-24.

- ^ Glass & Kohrman 2005, p. 10

- ^ (Unlisted) 1887, p. 237

- ^ a b Indiana Department of Inspection 1901, p. 36

- ^ a b Indiana Department of Inspection 1901, pp. 89–90

- ^ Glass & Kohrman 2005, p. 7

- ^ (Unlisted) 1887, p. 760

- ^ Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, p. 19

- ^ a b c Revi 1964, p. 198

- ^ a b c Batty 1978, p. 253

- ^ a b "US Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions". National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- ^ Burdekin & Siklos 2004, p. 38

- ^ "A Union Labor Fight". Indianapolis Journal (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). 1899-03-10. p. 3 (top center column).

Dunkirk glass Man Arrested for Discharging Union Men

- ^ "Labor Law Unconstitutional". Indianapolis Journal (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). 1899-03-23. p. 3 (3rd column from right toward bottom).

...the matter will be carried to the Supreme Court of Indiana....

- ^ a b c Hawkins 2009, p. 380

- ^ "Many Plants Unionized". Indianapolis Journal (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). 1899-12-22. p. 2 (3rd col. from left, toward bottom).

...formerly known as the Beatty-Brady Company, which has always operated nonunion, is one of the plants which will start Jan. 1 with union employes [sic].

- ^ "Will Try New Method of Operating Plant". Indianapolis Journal (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). 1904-01-23. p. 5 (2nd col. from right, toward bottom).

National Glass Company to Cut Down Working Force - Will Run on Individual Basis

- ^ a b "Operate Beatty-Brady Plant" (PDF). Indianapolis Journal (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). 1904-01-29. p. 2 (lower right).

The Indiana Glass Company, a new organization....

- ^ "Strike of Glass Workers". Indianapolis Journal (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). 1904-02-11. p. 3 (bottom of page).

Two hundred and fifty workmen are thrown out of employment.

- ^ "Glass Plants to Resume". Plymouth Tribune (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). 1904-03-03. p. 3 (3rd col. from right toward bottom).

...amicably settled and work will be resumed....

- ^ Hawkins 2009, p. 288

- ^ Indiana Department of Inspection 1902, p. 37

- ^ a b Jay & Montgomery 1922, p. 120

- ^ Indiana Department of Inspection 1905, p. 48

- ^ a b c Shotwell 2002, p. 257

- ^ Venable et al. 2000, p. 489

- ^ a b "Indiana Glass Co. Buys Plant at Hartford City; Factory Will Resume Operations n Near Future". American Flint. Toledo, Ohio: American Flint Glass Workers' Union. April 1953.

- ^ a b Kovel & Kovel 1991, p. 96

- ^ Moody Manual Company 1908, p. 2403

- ^ "National Plants Sold at Sacrifice". Fairmont West Virginian (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). 1908-11-11. p. 8 (left side).

Glass Concern Goes Out of Receiver's Hands and Will be Operated

- ^ a b Jay & Montgomery 1922, p. 121

- ^ "Pittsburgh News". Pottery Glass and Brass Salesman. New York: O'Gorman Publishing Company. 1921-03-10. Retrieved 2018-07-07.

- ^ Jay & Montgomery 1922, pp. 352–353

- ^ "Trade Notes". American Flint. Toledo, OH: American Flint Glass Workers Union. January 1916.

- ^ a b "Dunkirk (page 28)". American Flint. Toledo, OH: American Flint Glass Workers Union. August 1916.

- ^ a b US patent 1,331,792, "Glass Molding Machine", issued 1920-02-24.

- ^ United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce 1917, p. 61

- ^ Blackiston, G. P. (July 1906). "The Magnitude of the Glass Industry in the United States". Business Man's Magazine and the Book-Keeper. Detroit, Michigan: Book-Keeper Publishing Co., Ltd. Retrieved 2022-10-07.

- ^ "Trade Notes". American Flint. Toledo, OH: American Flint Glass Workers Union. August 1916.

- ^ a b Jay & Montgomery 1922, p. 353

- ^ "Fall Announcement Horace C. Gray Company (advertisement)". The Pottery, Glass & Brass Salesman. New York: Gorman Publishing Company. 1921-08-11. Retrieved 2018-06-21.

- ^ "Indiana Glass advertisement on page 71". Pottery Glass and Brass Salesman. New York: O'Gorman Publishing Company. 1921-02-17. Retrieved 2018-07-07.

- ^ a b Witzel 1994, p. 172

- ^ "Jay County Obituaries". Commercial–Review (Portland, Indiana). 1958-02-13. p. 1.

He worked his way from his first position as bookkeeper to paymaster, treasurer, vice-president and, on Frank W. Merry's death in 1931, to president.

- ^ "History of Several Major Producers of Depression Glass Part One" (PDF). National Depression Glass Association. Retrieved 2018-07-14.

- ^ United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce 1917, p. 67

- ^ Weeks & United States Census Office 1884, p. 43

- ^ United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce 1917, p. 62

- ^ "Forming Process - Gob Formation and Shapes". Glass Packaging Institute. Retrieved 2022-04-21.

- ^ United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce 1917, p. 64

- ^ US patent 1,190,145, "Automatic Centrifugal Glassware-Making Machinery", issued 1916-07-04.

- ^ United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce 1917, p. 65

- ^ US patent 1,807,336, "Glass Gob Disposing Means", issued 1931-05-26.

- ^ US patent 1,978,695, "Revolving Tray", issued 1934-10-30.

- ^ "Women in Business - Grandma's House features antique and collectible glass". Kerrville Daily Times. 2005-03-14. p. 28.

- ^ Florence & Florence 2006, p. 21

- ^ Kovel & Kovel 1991, p. 16

- ^ a b c "Chairs and music boxes among finds". Lawrence Journal World. 2009-07-05. p. 7D.

- ^ a b Florence & Florence 2006, p. 242

- ^ Kovel & Kovel 1991, p. 46

- ^ Kovel & Kovel 1991, p. 60

- ^ Florence & Florence 2006, p. 148

- ^ a b Venable et al. 2000, p. 424

- ^ Kovel & Kovel 1991, p. 76

- ^ "Tiara Exclusives' Glass Giftware is Perfect for Year Around Gift Giving". Defiance Crescent News. 1980-02-22. p. 14.

- ^ Florence & Florence 2006, p. 223

- ^ Kovel & Kovel 1991, p. 83

- ^ "Lancaster Lens Company Acquires Controlling Interest in Indiana Glass". The Glass Industry. New York: Magazines For Industry, Incorporated. April 1957.

- ^ "Lancaster Name Change Result of Diversification". The Glass Industry. New York: Magazines For Industry, Incorporated. May 1957.

- ^ a b "Form 10-K Lancaster Colony Corporation for the fiscal year ended June 30, 1994". Securities and Exchange Commission. Retrieved 2018-08-05.

- ^ "Lancaster Colony Buys Bischoff Glass". Lancaster Eagle Gazette. 1963-01-23. p. 1.

- ^ Pederson 2004, p. 172

- ^ a b "FTC Challenges Dunkirk Merger". Anderson Herald Bulletin. 1977-06-29. p. 28.

- ^ a b "Workers Voting on Wage Cut". Anderson Daily Bulletin. 1986-10-03. p. 28.

- ^ Subcommittee on Trade of the Committee on Ways and Means, U.S. House of Representatives 1991, pp. 857–858

- ^ "Form 10-K Lancaster Colony Corporation for the fiscal year ended June 30, 1999". Securities and Exchange Commission. Retrieved 2018-08-11.

- ^ "Form 10-K Lancaster Colony Corporation for the fiscal year ended June 30, 2002". Securities and Exchange Commission. Retrieved 2018-08-11.

- ^ a b "Talks stall at Dunkirk glass factory". Logansport Pharos-Tribune. 2001-12-16. p. A6.

- ^ "Production ends at Indiana glass plant". Kokomo Tribune. 2002-11-28. p. A10.

- ^ Alexander 2017, p. 94

- ^ "Dunkirk struggling to balance loss of industry". Kokomo Tribune. 2003-12-16. p. 1 (of business section).

- ^ Alexander 2017, pp. 95–96

- ^ Wilson, Paul (2007-11-19). "Glass news brightens Lancaster's jobs picture". Columbus Dispatch. Retrieved 2022-08-18.

References

- Alexander, Brian (2017). Glass house : The 1% Economy and the Shattering of the All-American Town. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-1-25008-580-1. OCLC 947146034.

- Batty, Bob H. (1978). A Complete Guide to Pressed Glass. Gretna: Pelican Publishing Co. OCLC 640179409.

- Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) (1986). A History of Blackford County, Indiana : with Historical Accounts of the County, 1838–1986 [and] Histories of Families who have Lived in the County. Hartford City, Indiana: Blackford County Historical Society. OCLC 15144953.

- Burdekin, Richard C. K.; Siklos, Pierre L. (2004). Deflation: Current and Historical Perspectives. Image of America. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83799-6. Retrieved 2018-07-04.

- Florence, Gene; Florence, Cathy Gains (2006). Collector's Encyclopedia of Depression Glass. Paducah, Kentucky: Collector Books. ISBN 9781574324693. OCLC 1035928761.

- Glass, James A.; Kohrman, David (2005). The Gas Boom of East Central Indiana. Image of America. Charleston, SC: Arcadia. ISBN 978-0-7385-3963-8. OCLC 61885891. Retrieved 2013-03-17.

- Hawkins, Jay W. (2009). Glasshouses and Glass Manufacturers of the Pittsburgh Region, 1795-1910. New York: iUniverse. ISBN 978-1-44011-717-6. OCLC 429680614.

- Indiana Department of Inspection (1901). Annual Report of the Department of Inspection of the State of Indiana (1900). Indianapolis: William B. Burford. OCLC 13018336. Retrieved 2018-06-24.

- Indiana Department of Inspection (1902). Annual Report of the Department of Inspection of Manufacturing and Mercantile Establishments, Laundries, Bakeries, Quarries, Printing Offices and Public Buildings (1901). Indianapolis: William B. Burford. OCLC 13018369. Retrieved 2018-07-10.

- Indiana Department of Inspection (1905). Annual Report of the Department of Inspection of the State of Indiana (1904). Indianapolis: William B. Burford. OCLC 13018336. Retrieved 2018-07-03.

- Jay, Milton T.; Montgomery, M.W. (1922). History of Jay County, Indiana : Including its World War Record and Incorporating the Montgomery History (Vol. II). Indianapolis: Historical Publishing Co. OCLC 5976187.

- Kovel, Ralph M.; Kovel, Terry H. (1991). Kovels' Depression Glass & American Dinnerware Price List. New York: Crown Publishers. ISBN 978-0-51758-444-6.

- Moody Manual Company (1908). Moody's Manual of Railroads and Corporate Securities. New York: Moody Publishing Company. OCLC 5584364.

- Pederson, Jay P. (2004). International Directory of Company Histories - Volume 61. Chicago: St. James Press. OCLC 43262799.

- Revi, Albert Christian (1964). American Pressed Glass and Figure Bottles. New York: Nelson. OCLC 965803.

- Shotwell, David J. (2002). Glass A to Z. Iola, WI: Krause Publications. ISBN 978-0-87349-385-7. OCLC 440702171.

- Subcommittee on Trade of the Committee on Ways and Means, U.S. House of Representatives (1991). Proposed Negotiation of a Free Trade Agreement with Mexico : Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Trade of the Committee on Ways and Means, House of Representatives, One Hundred Second Congress, First Session, February 20, 21, and 28, 1991. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 998. ISBN 978-0-16035-464-9. OCLC 24476998.

- United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce (1917). The Glass Industry. Report on the Cost of Production of Glass in the United States. Washington: Government Printing Office. OCLC 5705310.

Glass blower.

- (Unlisted) (1887). Biographical and Historical Record of Jay and Blackford Counties, Indiana: Containing ... Portraits and Biographies of Some of the Prominent Men of the State : Engravings of Prominent Citizens in Jay and Blackford Counties, with Personal Histories of Many of the Leading Families and a Concise History of Jay and Blackford Counties and their Cities and Villages. Image of America. Chicago: The Lewis Publishing Company. OCLC 15560416. Retrieved 2018-06-24.

- Venable, Charles L.; Jenkins, Tom; Denker, Ellen P.; Grier, Katherine C.; Harrison, Stephen G. (2000). China and Glass in America, 1880-1980: from Tabletop to TV Tray. Dallas: Dallas Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-81096-692-5. OCLC 905439701.

- Weeks, Joseph Dame; United States Census Office (1884). Report on the Manufacture of Glass. Washington: Government Printing Office. OCLC 2123984.

report on the manufacture of glass.

- Witzel, Michael K. (1994). The American Drive-In. Osceola, WI: Motorbooks International. ISBN 978-0-87938-919-2. OCLC 243806787.

Further reading

- Adler, Donna (2005). Indiana Glass Company of Dunkirk, IN, 1907-2002. Carnival Heaven. OCLC 58541047.

- Craig S., Schenning (2005). A Century of Indiana Glass. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-76432-303-4. OCLC 62338861.

- Craig S., Schenning (2016). The Collector's Encyclopedia of Indiana Glass: A Glassware Pattern Identification Guide, Volume 1, Early Pressed Glass Era Patterns, (1898 - 1926), Volume 1. Hampstead, Maryland: Maple Creek Media. p. 197. ISBN 978-1-94291-413-6. OCLC 957470932.