Greeks in Italy

Cemetery behind San Giorgio dei Greci, Venice | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 90.000 - 110.000d [1][2][3] | |

| Languages | |

| Italian, Greek, Griko | |

| Religion | |

| Catholic, Greek Orthodox |

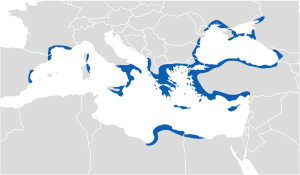

Greek presence in Italy began with the migrations of traders and colonial foundations in the 8th century BC, continuing down to the present time. Nowadays, there is an ethnic minority known as the Griko people,[4] who live in the Southern Italian regions of Calabria (Province of Reggio Calabria) and Apulia, especially the peninsula of Salento, within the ancient Magna Graecia region, who speak a distinctive dialect of Greek called Griko.[5] They are believed to be remnants of the ancient[6] and medieval Greek communities, who have lived in the south of Italy for centuries. A Greek community has long existed in Venice as well, the current centre of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Italy and Malta, which in addition was a Byzantine province until the 10th century and held territory in Morea and Crete until the 17th century. Alongside this group, a smaller number of more recent migrants from Greece lives in Italy, forming an expatriate community in the country. Today many Greeks in Southern Italy follow Italian customs and culture, experiencing assimilation.

Ancient

In the 8th and 7th centuries BC, for various reasons, including demographic crisis (famine, overcrowding, climate change, etc.), the search for new commercial outlets and ports, and expulsion from their homeland, Greeks began a large colonization drive, including southern Italy.[7]

In this same time, Greek colonies were established in places as widely separated as the eastern coast of the Black Sea and Massalia (Marseille). They included settlements in Sicily and the coastal areas of the southern part of the Italian peninsula.[8] The Romans called the area of Sicily and the foot of the boot of Italy Magna Graecia (Latin, "Greater Greece"), since it was so densely inhabited by Greeks. The ancient geographers differed on whether the term included Sicily or merely Apulia and Calabria — Strabo being the most prominent advocate of the wider definitions.

Medieval

During the Early Middle Ages, new waves of Greeks came to Magna Graecia from Greece and Asia Minor, as Southern Italy remained governed by the Eastern Roman Empire. Although most of the Greek inhabitants of Southern Italy became de-Hellenized and no longer spoke Greek, remarkably a small Griko-speaking minority still exists today in Calabria and mostly in Salento. Griko is the name of a language combining ancient Doric, Byzantine Greek, and Italian elements, spoken by people in the Magna Graecia region. There is rich oral tradition and Griko folklore, limited now, though once numerous, to only a few thousand people, most of them having become absorbed into the surrounding Italian element. Records of Magna Graecia being predominantly Greek-speaking date as late as the 11th century (the end of the Byzantine empire what is commonly known as the Eastern Roman Empire). Recall that the Roman empire had become so vast that it was divided into two parts for administrative purposes.

The migration of Byzantine Greek scholars and other emigres from Byzantium during the decline of the Byzantine empire (1203–1453) and mainly after the fall of Constantinople in 1453 until the 16th century, is considered by modern scholars as crucial in the revival of Greek and Roman studies, arts and sciences, and subsequently in the development of Renaissance humanism.[12] These emigres were grammarians, humanists, poets, writers, printers, lecturers, musicians, astronomers, architects, academics, artists, scribes, philosophers, scientists, politicians and theologians.[13]

In the decades following the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople many Greeks began to settle in territories of the Republic of Venice, including in Venice itself. In 1479 there were between 4000 and 5000 Greek residents in Venice.[14] Moreover, it was one of the economically strongest Greek communities of that time outside the Ottoman Empire.[15] In November 1494 the Greeks in Venice asked permission and were permitted to found a confraternity, the Scuola dei Greci,[16] a philanthropic and religious society which had its own committee and officers to represent the interests of the flourishing Greek community. This was the first official recognition of the legal status of the Greek colony by the Venetian authorities.[17] In 1539 the Greeks of Venice were permitted to begin building their own church, the San Giorgio dei Greci which still stands in the centre of Venice in the present day on the Rio dei Greci.[17]

Modern Italy

| Part of a series on |

| Greeks |

|---|

|

|

History of Greece (Ancient · Byzantine · Ottoman) |

Although most of the Greek inhabitants of Southern Italy became entirely Latinized during the Middle Ages (as many ancient colonies like Paestum had already been in the 4th century BC), pockets of Greek culture and language remained and survived into modern times. This is due to the fact that the migration routes between southern Italy and the Greek mainland never entirely ceased to exist.

Thus, for example, Greeks sought refuge in the region in the 16th and 17th centuries in reaction to the conquest of the Peloponnese by the Ottoman Turks, especially after the fall of Coroni (1534). The Greeks from Coroni - the so-called Coronians - belonged to the nobility and brought with them substantial movable property. They were granted special privileges and given tax exemptions. Another part of the Greeks that moved to Italy came from the Mani region of the Peloponnese. The Maniots were known for their proud military traditions and for their bloody vendettas (another portion of these Greeks moved to Corsica; cf. the Corsican vendettas).[citation needed]

When the Italian Fascists gained power in 1922, they persecuted the Greek-speakers in Italy.[18][19] Today the Italian Greek is included in UNESCO's Red Book of Endangered Languages.[19]

Griko people

The Griko people are a population group in Italy of ultimately Greek origin which still exists today in the Italian regions of Calabria and Apulia.[20] The Griko people traditionally spoke the Griko language, a form of the Greek language combining ancient Doric and Byzantine Greek elements. Some believe that the origins of the Griko language may ultimately be traced to the colonies of Magna Graecia. Greeks were the dominant population element of some regions in the south of Italy, especially Calabria, the Salento, parts of Lucania and Sicily until the 12th century.[21][22] Over the past centuries the Griko have been heavily influenced by the Catholic Church and Latin culture and as a result, many Griko have become largely assimilated[23] into mainstream Italian culture, though once numerous, the Griko are now limited, most of them having become absorbed into the surrounding Italian element. The Griko language is severely endangered due to language shift towards Italian and large-scale internal migration to the cities in recent decades.[24] The Griko community is currently estimated at 60,000 members.[25][26]

Immigrants

After World War II, a large number of Greeks immigrated to countries abroad, mostly to the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, The United Kingdom, Argentina, Brazil, Norway, Germany, United Arab Emirates, and Singapore. however, a smaller number of diaspora migrants from Greece entered Italy from World War II onwards, today the Greek diaspora community consists of some 30,000 people, the majority of whom are located in Rome and Central Italy.[27]

Notable Greeks in Italy

- Peter of Candia antipope (1339–1410)

- Pope Innocent VIII (1432-1492)

- Francesco Maurolico mathematician and astronomer (1494-1575)

- Nicholas Kalliakis philosopher (1645-1707)

- Andreas Musalus mathematician and philosopher (1665-1721)

- Simone Stratigo mathematician and natural science expert (1733–1824)

- Ugo Foscolo writer, revolutionary and poet (1778–1827)

- Constantino Brumidi historical painter (1805-1880)

- Matilde Serao journalist and novelist (1856–1927)

- Sotirios Bulgaris founder of Bvlgari jewelry (1857-1932)

- Demetrio Stratos singer (1945–1979)

- Antonella Lualdi actress and singer (1931)

- Sylva Koscina actress (1933)

- Fiorella Kostoris economist (1945)

- Antonella Interlenghi actress (1960)

- Anna Kanakis actress and model (1962)

- Valeria Golino actress (1965)

- Virginia Sanjust di Teulada television announcer (1977)

- Nicolas Vaporidis actor (1982)

- Chiara Gensini actress (1982)

- Ria Antoniou model and actress (1988)

- Ludovica Caramis model (1991)

- Kostas Manolas footballer (1991)

See also

- Calabrian Greek dialect

- Colonies in antiquity

- Greek coinage of Italy and Sicily

- Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Italy and Malta

- Griko language

- Magna Graecia

- Grecìa Salentina

- Bovesia

References

- ^ "Grecia Salentina official site (in Italian)". www.greciasalentina.org.org. Archived from the original on December 31, 2010. Retrieved February 1, 2011.

La popolazione complessiva dell'Unione è di 54278 residenti così distribuiti (Dati Istat al 31° dicembre 2005. Comune Popolazione Calimera 7351 Carpignano Salentino 3868 Castrignano dei Greci 4164 Corigliano d'Otranto 5762 Cutrofiano 9250 Martano 9588 Martignano 1784 Melpignano 2234 Soleto 5551 Sternatia 2583 Zollino 2143 Totale 54278

- ^ Bellinello, Pier Francesco (1998). Minoranze etniche e linguistiche. Bios. p. 53. ISBN 9788877401212.

Le attuali colonie Greche calabresi; La Grecìa calabrese si inscrive nel massiccio aspromontano e si concentra nell'ampia e frastagliata valle dell'Amendolea e nelle balze più a oriente, dove sorgono le fiumare dette di S. Pasquale, di Palizzi e Sidèroni e che costituiscono la Bovesia vera e propria. Compresa nei territori di cinque comuni (Bova Superiore, Bova Marina, Roccaforte del Greco, Roghudi, Condofuri), la Grecia si estende per circa 233 kmq. La popolazione anagrafica complessiva è di circa 14.000 unità.

- ^ "Hellenic Republic Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Italy, The Greek Community". Archived from the original on July 17, 2006. Retrieved October 12, 2015.

Greek community. The Greek diaspora consists of some 30,000 people, most of whom are to be found in Central Italy. There has also been an age-old presence of Italian nationals of Greek descent, who speak the Greco dialect peculiar to the Magna Graecia region. This dialect can be traced historically back to the era of Byzantine rule, but even as far back as classical antiquity.

- ^ PARDO-DE-SANTAYANA, MANUEL; Pieroni, Andrea; Puri, Rajindra K. (2010). Ethnobotany in the new Europe: people, health and wild plant resources. Berghahn Books. pp. 173–174. ISBN 978-1-84545-456-2.

ISBN 1-84545-456-1" "The ethnic Greek minorities living in southern Italy today exemplify the establishment of independent and permanent colonial settlements of Greeks in history.

- ^ "Greek MFA: Greek community in Italy". Archived from the original on July 17, 2006. Retrieved April 4, 2008.

- ^ G. Rohlfs, Griechen und Romanen in Unteritalien, 1924.

- ^ "Greek Italy:A Roadmap". Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved April 4, 2008.

- ^ "Magna Graecia". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ Clagett, Marshall; Archimedes (1988). Archimedes in the Middle Ages, Volume 3. The American Philosophical Society. p. 749. ISBN 0-87169-125-6.

Initially, we should observe that Francesco Maurolico (or Maruli or Maroli) was born in Messina on 16 September 1494, of a Greek family which had fled Constantinople after its fall to the Turks in 1453 and settled in Messina.

- ^ Cotterell, John (1996). Social Networks and Social Influences in Adolescence. Routledge. p. 34. ISBN 0-415-10973-6.

Francisco Maurolico, the son of Greek refugees from Constantinople, spread an interest in number theory through his study of arithmetic in two books published in 1575 after his death.

- ^ Biucchi, Edwina; Pilling, Simon; Collie, Keith (2002). Venice: an architectural guide. Batsford. ISBN 0-7134-8781-X.

Tommaso Flangini, a wealthy Greek merchant and . in 1664 . a late entrant to the Venetian Republic's patriciate) were enclosed.

- ^ "Byzantines in Renaissance Italy". Archived from the original on August 31, 2018. Retrieved April 4, 2008.

- ^ Greeks in Italy

- ^ Nicol, Donald M. (1994). The Byzantine Lady: Ten Portraits, 1250–1500. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 104. ISBN 0-521-45531-6.

In 1479 it was reckoned that there were between 4000 and 5000 Greek residents in Venice. They were not idle scroungers, they served the interests of their hosts in a number of ways.

- ^ Greece: Books and Writers (PDF). Ministry of Culture — National Book Centre of Greece. 2001. p. 54. ISBN 960-7894-29-4.

- ^ Nicol, Donald M. (1988). Byzantium and Venice: A Study in Diplomatic and Cultural Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 416. ISBN 0-521-34157-4.

In November 1494 the Greeks asked permission to form a Brotherhood of the Greek race.

- ^ a b Nicol, Donald M. (1994). The Byzantine Lady: Ten Portraits, 1250–1500. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 104. ISBN 0-521-45531-6.

In 1494 the Greeks in Venice were permitted to found a Brotherhood of the Greek race, a philanthropic and religious society with its own officers and committee to represent the interests of the Greek community. It was the first formal recognition by Venice of the legal status of the Greek colony. But it was not until 1539 that they were authorized to begin building their own church of San Giorgio dei Greci which still stands in the centre of Venice on the Rio dei Greci.

- ^ Minority Rights Group International - Italy - Greek-speakers

- ^ a b Alan Clarke (2015). Allan Jepson (ed.). Managing and Developing Communities, Festivals and Events. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 137. ISBN 978-1137508539.

- ^ Bekerman Zvi; Kopelowitz, Ezra (2008). Cultural education-- cultural sustainability: minority, diaspora, indigenous, and ethno-religious groups in multicultural societies. Routledge. p. 390. ISBN 978-0-8058-5724-5.

ISBN 0-8058-5724-9" "Griko Milume - This reaction was even more pronounced in the southern Italian communities of Greek origins. There are two distinct clusters, in Puglia and Calabria, which have managed to preserve their language, Griko or Grecanico, all through the historical events that have shaped Italy. While being Italian citizens, they are actually aware of their Greek roots and again the defence of their language is the key to their identity.

- ^ Loud, G. A. (2007). The Latin Church in Norman Italy. Cambridge University Press. p. 494. ISBN 978-0-521-25551-6.

ISBN 0-521-25551-1" "At the end of the twelfth century ... While in Apulia Greeks were in a majority – and indeed present in any numbers at all – only in the Salento peninsula in the extreme south, at the time of the conquest, they had an overwhelming preponderance in Lucaina and central and southern Calabria, as well as comprising anything up to a third of the population of Sicily, concentrated especially in the north-east of the island, the Val Demone.

- ^ Kleinhenz, Christopher (2004). Medieval Italy: an encyclopedia, Volume 1. Routledge. pp. 444–445. ISBN 978-0-415-93930-0.

ISBN 0-415-93930-5" "In Lucania (northern Calabria, Basilicata, and southernmost portion of today's Campania) ... From the late ninth century into the eleventh, Greek-speaking populations and Byzantine temporal power advanced, in stages but by no means always in tandem, out of southern Calabria and the lower Salentine peninsula across Lucania and through much of Apulia as well. By the early eleventh century, Greek settlement had radiated northward and had reached the interior of the Cilento, deep in Salernitan territory. Parts of the central and north-western Salento recovered early, and came to have a Greek majority through immigration, as did parts of Lucania.

- ^ Pounds, Norman John Greville (1976). An historical geography of Europe, 450 B.C.-A.D.1330. CUP Archive. p. 251. ISBN 978-0-521-29126-2.

ISBN 0-521-29126-7" "Greeks had also settled in southern Italy and Sicily which retained until Norman conquest a tenuous link with Constantinople. At the time of the Norman invasion, the Greeks were a very important minority, and their monasteries provided the institutional basis for the preservation of Greek culture. The Normans, however, restored the balance and permitted Latin culture to reassert itself. By 1100 the Greeks were largely assimilated and only a few colonies remained in eastern Sicily and Calabria; even here Greek lived alongside and intermarried with Latin, and the Greek colonies were evidently declining.

- ^ Moseley, Christopher (2007). Encyclopedia of the world's endangered languages. Routledge. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-7007-1197-0.

ISBN 0-7007-1197-X" "Griko (also called Italiot Greek) Italy: spoken in the Salento peninsula in Lecce Province in southern Apulia and in a few villages near Reggio di Calabria in southern Calabria ... South Italian influence has been strong for a long time. Severely Endangered.

- ^ "Grecia Salentina official site (in Italian)". www.greciasalentina.org.org. Archived from the original on December 31, 2010. Retrieved February 1, 2011.

La popolazione complessiva dell'Unione è di 54278 residenti così distribuiti (Dati Istat al 31° dicembre 2005. Comune Popolazione Calimera 7351 Carpignano Salentino 3868 Castrignano dei Greci 4164 Corigliano d'Otranto 5762 Cutrofiano 9250 Martano 9588 Martignano 1784 Melpignano 2234 Soleto 5551 Sternatia 2583 Zollino 2143 Totale 54278

- ^ Bellinello, Pier Francesco (1998). Minoranze etniche e linguistiche. Bios. p. 53. ISBN 978-88-7740-121-2.

ISBN 88-7740-121-4" "Le attuali colonie Greche calabresi; La Grecìa calabrese si inscrive nel massiccio aspromontano e si concentra nell'ampia e frastagliata valle dell'Amendolea e nelle balze più a oriente, dove sorgono le fiumare dette di S. Pasquale, di Palizzi e Sidèroni e che costituiscono la Bovesia vera e propria. Compresa nei territori di cinque comuni (Bova Superiore, Bova Marina, Roccaforte del Greco, Roghudi, Condofuri), la Grecia si estende per circa 233 kmq. La popolazione anagrafica complessiva è di circa 14.000 unità.

- ^ "Hellenic Republic Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Italy, The Greek Community".

Greek community. The Greek diaspora consists of some 30,000 people, most of whom are to be found in Central Italy. There has also been an age-old presence of Italian nationals of Greek descent, who speak the Greco dialect peculiar to the Magna Graecia region. This dialect can be traced historically back to the era of Byzantine rule, but even as far back as classical antiquity.

Further reading

Jonathan Harris, 'Being a Byzantine after Byzantium: Hellenic Identity in Renaissance Italy', Kambos: Cambridge Papers in Modern Greek 8 (2000), 25-44

Jonathan Harris, Greek Emigres in the West, 1400–1520 (Camberley, 1995)

Jonathan Harris and Heleni Porphyriou, 'The Greek diaspora: Italian port cities and London, c. 1400–1700', in Cities and Cultural Transfer in Europe: 1400–1700, ed. Donatella Calabi and Stephen Turk Christensen (Cambridge, 2007), pp. 65–86

Heleni Porphyriou, 'La presenza greca in Italia tra cinque e seicento: Roma e Venezia', La città italiana e I luoghi degli stranieri XIV-XVIII secolo, ed. Donatella Calabi and Paolo Lanaro (Rome, 1998), pp. 21–38

M.F. Tiepolo and E. Tonetti, I Greci a Venezia. Atti del convegno internazionale di studio, Venezia, 5-8 Novembre 1998 (Venice, 2002), pp. 185–95

External links

- Grika milume! An online Griko community

- Enosi Griko, Coordination of Grecìa Salentina Associations

- Grecìa Salentina Archived March 24, 2005, at the Wayback Machine official site (in Italian)

- Salento Griko (in Italian)

- English-Griko dictionary