Emergency childbirth

This article needs more reliable medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources. (October 2023) |  |

Emergency childbirth is the precipitous birth of an infant in an unexpected setting. In planned childbirth, mothers choose the location and obstetric team ahead of time. Options range from delivering at home, at a hospital, a medical facility or a birthing center. Sometimes, birth can occur on the way to these facilities, without a healthcare team. The rates of unplanned childbirth are low.[1][2][3] If the birth is imminent, emergency measures may be needed.[4] Emergency services can be contacted for help in some countries.[5][6]

Emergency childbirth can follow the same steps as a planned childbirth. However, the birth can have increased risks for complications due to the prematurity of the baby or the less than ideal location.

Background

In 2020, 1.34% of births took place outside of a hospital in California, USA,[7] where 1 out of 8 births in the country happen.[8] Most of the out-of-hospital births are planned, and thus, not considered an emergency childbirth.[9] However, about 12% of attempted home deliveries need urgent transport to a hospital. Some of the reasons for transferring to a hospital include failure of labor to progress, parental exhaustion, need for more pain medication, or parental/fetal complications.[10]

In the United States, 0.61% of all births happen in an unplanned setting. The percent is even lower in countries like Finland and France.[5]

Each year more than 250,000 women around the world die from complications due to childbirth or pregnancy, with bleeding and hypertension as the leading causes.[11] Many of these deaths are preventable by emergency care, which include antibiotics, drugs that stimulate contraction of the uterus, anti-seizure drugs, blood transfusion, and delivery of baby with assistance (vacuum or forceps delivery) or C-section.[11] In addition, it is important to prevent hypothermia in the newborn because this is linked to poor outcomes.[12]

Preparation

Many pregnant women seek medical care throughout pregnancy and plan for the birth of a baby with a healthcare team. Access to high quality care lowers the risk adverse events in pregnancy.[13] In an emergency childbirth situation, it is recommended to seek further education and make a plan.[14]

Early preparation

Many childbirth education classes cover emergency birth procedures. Parents are trained to learn the signs of early labor or other indications that may require assistance. Signs of early labor include regular contractions (4 or more within one hour) accompanied with cervical changes, such as effacement or dilation.[15] Caregivers can take a class on infant and child life support. Some recommend having a kit of emergency supplies in the home such as: clean towels, receiving blanket, sheets, clean scissors, clean clamps or ties, ID bands for mother and baby, pencil, soap, sterile gloves, sanitary pads, diapers, and instructions for infant-rescue breathing.[16][17][18]

Late preparation

Additional help may be found by calling 911 (in the United States) or an applicable number to get emergency medical services or nearby medical staff.[19]

A vehicle driven safely toward medical care may be considered an acceptable option during the first stage of labor (dilation and effacement). During the second stage of labor (pushing and birth), a vehicle is usually stopped unless imminently arriving at a medical facility. If a vehicle is taken, additional occupants can support the mother and baby should assist in delivery. The mother and baby are kept warm throughout.[20]

If unable to reach a medical facility, a safe building with walls and a roof are sought that will provide protection from the environment. A warm and dry area with a bed is preferable.[18]

Supplies are collected for both the mother and the baby. Possible supplies may include blankets, pillows, towels, warm clean water, warm water bottles, soap, clean towels, baby clothes, sheets, sterile gloves, sanitary pads, diapers, identification tags for mother and baby, and instructions for infant-rescue breathing.[16][17][18] A bed may be prepared for the baby with a basket or box lined with a blanket or sheets.[18] Items are needed to clamp or tie the umbilical cord in two places. Shoestrings or strips of a sheet folded into narrow bands may be used.[18] These items can be sterilized by boiling (20 minutes) or soaking in alcohol (up to 3 hours).[18] Scissors or a knife are needed to cut the umbilical cord and may be sterilized with the same procedure.[18]

Evaluation

A background obstetric history should be obtained: how many prior births has the patient had (if this is not her first birth, the patient's labor could be short), how many weeks along is she or what is her estimated date of delivery, any special concerns related to this pregnancy such as being told she has twins, being told she has a complication, or even if she has received regular prenatal care. Any other relevant medical history, allergies, drugs, recent signs of infections (fever) should be asked.[10]

Signs and symptoms

- Any gush of fluid? This would indicate that the rupture of membranes has occurred releasing amniotic fluid and that labor will probably begin soon if the patient is near term.[10][21]

- Any vaginal bleeding? Could indicate a bloody show, a small amount of bloody discharge prior to labor, or if large amounts of bleeding occurred it could indicate potentially life-threatening complications.[10]

- How frequent are her contractions? One common recommendation is the patient may be in active labor if contractions are 5 minutes apart for one hour (if rupture of membranes has not occurred).[10][21]

- Does she feel the urge to push with her contractions? This is an indication delivery will occur soon.[19]

- Pregnancy and Prenatal History? Certain conditions can increase the risk of complications during labor, including preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, parental obesity, and more.[22]

Physical exam

If time permits and if trained: one should obtain vital signs to include maternal heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, temperature, and oxygen rate.[10]

The patient should be draped with available blankets for privacy.

The patient's abdomen should be examined and felt for the presence of contractions,[10] and the intensity, frequency, and length of contractions should be noted.[21]

With the patient's permission and privacy, an exam of the pelvic area should be performed; in general, one would:

- Inspect to see if there is any presenting part of the baby. The baby's head will feel hard versus their buttocks will feel soft.[19]

- If the baby's head is presenting out of the vagina (crowning), then delivery will be happening soon and preparation should begin to deliver the baby[19]

- Trained physicians would conduct a manual cervical exam to determine the patient's cervical dilation.

After the physical exam and if the patient is not crowning, the patient should be placed in the left lateral decubitus position (laying on her left side).[10]

Delivery of term baby in normal position

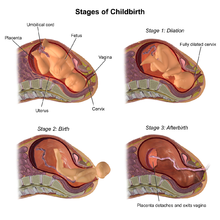

First stage of labor: dilation and effacement of the cervix

This stage of labor on average lasts from 2 to 18 hours, but can last even longer in normal pregnancies.[23] This stage can be further broken up into the latent stage and active stage depending on how dilated the cervix is. The latent stage, when the cervix is dilated less than 3-5 cm along with regular contractions, can last as long as 20 hours without being considered prolonged. The active stage, when regular contractions are accompanied with dilation greater than 3-5 cm, can also be significantly long, with anything less than 11.7 hours being considered normal.[24] Further care may be sought during this time.

- Evaluation (above) is repeated, assessing for change in stage of labor.[25][23]

- The mother is encouraged to walk or sit in a comfortable position.[21][25][23]

Second stage: cervix is dilated

This stage may last from 5 minutes to 3 hours.[23]

- Position. The mother is positioned in the lithotomy position, lying on her back, with her feet above or at the same level as the hips. The perineum (the space between the vagina and anus) is positioned at the edge of a bed.[25][23]

- Wash. The perineum is cleaned with antiseptic solution or soap and water.[18] Any assistants will wash hands with soap and water and put on sterile or clean gloves.

- Pushing. Pushing is encouraged during contractions.[23][25]

- Head. The head of the baby is delivered. Delivery of the head is controlled to prevent rapid expulsion. One hand is placed on the perineum while the other applies gentle pressure to the baby's head as it comes out.[25] Soft pressure can be applied to the baby's chin through the perineum to help expel the head. Rapid expulsion is still prevented with soft head pressure to reduce vaginal lacerations.[25]

- Cord check. The presence of an umbilical cord (nuchal cord) is checked to determine if it is around the baby's neck.[23][25] If it is present, an index finger is used to attempt to pull it over the baby's head.[23][25] If this cannot be done, the cord is clamped/tied in two places. Then the cord is carefully cut, avoiding injury to the baby or mother.[23][25]

- Front shoulder. The front shoulder is delivered. This is the shoulder on the mother's front side, towards her belly. The assistant holds the baby's head with two hands and may need to apply slight downward pressure (towards the mother's anus) to help the front shoulder out. Firm pressure can injure the baby.[23][25] If the shoulder gets stuck this is called shoulder dystocia. There are certain risk factors for shoulder dystocia, including gestational diabetes.[22] See procedure for relief of shoulder dystocia (below).

- Back shoulder. The back shoulder is then delivered by providing slight upward pressure (away from the mother's anus).[25]

- Catch baby. The baby usually comes out right away after both shoulders.[25] The baby is caught carefully, considering that newborn babies can be slippery. The assistant holds the baby at the level of the vagina.

- Cut cord. The umbilical cord is clamped and cut. The cord is clamped in two places about 6 cm to 8 cm from the baby.[25] The clamps or ties are tight in order to stop the blood flow. The cord is cut between the two clamps or ties.[25][23] Sterilized scissors or a sterilized knife is used.[18] Another assistant may help with this.

- Dry baby. The baby is dried, wrapped, and kept warm. Appropriate neonatal care is provided or the baby is placed to the mother's breast on her bare skin.[14] An identification band may be placed on the baby.[18]

Third stage of labor: the delivery of the placenta

The baby is attached to the placenta by the umbilical cord. After the cord is cut, the placenta is usually still inside the mother. The placenta usually comes out in 2–10 minutes, but it may take up to 60 minutes.[18][23] This process is usually a spontaneous one, but may also require pushing from the mother.[22]

- Before the placenta is delivered there is a gush of blood as the cord gets longer.[25][23]

- The umbilical cord can be held taut, but must not be pulled with much force.[25]

- The placenta is delivered and is inspected for completeness. The placenta should be stored in a bag for inspection by trained medical personnel.[25][18]

- The mother will need to have a trained physician inspect for vaginal lacerations that will need suture repair.

Maternal complications

Complications of emergency childbirth include the complications that occur during normal childbirth. Potential complications for the gestational parent include perineal tearing (tearing of the vagina or surrounding tissue) during delivery, excessive bleeding (postpartum hemorrhage), hypertension (high blood pressure), and seizures.

Vaginal bleeding and shock

Bleeding during pregnancy is fairly common (experienced by up to 25% of pregnant women[26]) and may not always indicate a problem. However, bleeding can be a sign of a serious complication, including miscarriage or another condition that threatens the health of the mother or fetus. It is important to get medical attention for any of the following:

- Vaginal bleeding early or late in pregnancy

- Severe abdominal pain

- Trauma (such as a fall or car accident) while pregnant

- Uncontrolled vaginal bleeding after the baby is delivered (postpartum hemorrhage)

- Inability to remove the entire placenta after the baby is delivered (retained products of conception)

First trimester bleeding

Causes of vaginal bleeding early in pregnancy include miscarriage (including inevitable, incomplete, or complete abortion), embryo implantation and growth outside the uterus (ectopic pregnancy), and placenta attachment at the bottom of the uterus over the cervix (placenta previa), all of which can cause significant bleeding.

Vaginal bleeding early in pregnancy may also be a sign of a threatened abortion, which is when there is light to moderate vaginal bleeding but the cervix is still closed. Threatened abortion does not mean that miscarriage is inevitable; about 50% of women with bleeding before the third trimester will progress to a live birth.[27]

Bleeding after the first trimester and during delivery

Prior to and during delivery, bleeding can occur from tears in the cervix, vagina, or perineum, sudden placental detachment (placental abruption) and placental attachment over the cervix (placenta previa), and uterine rupture.

Bleeding after delivery (postpartum hemorrhage)

Postpartum hemorrhage occurs in 3% of pregnant women, leading to ~150,000 annual deaths worldwide. Hemorrhages are an indication to seek care from a healthcare provider. The hemorrhages are usually slow and continuous and can last more than 90 minutes after delivery before they are fatal to the mother. This time should be used to quickly transfer the woman to a hospital.

Postpartum hemorrhage is defined by “cumulative blood loss ≥1000 mL, or bleeding associated with signs/symptoms of hypovolemia within 24 hours of the birth process”.[28] It is difficult to predict and has few known risk factors. Once uncontrolled bleeding occurs, management can be manual (fundal massage from the outside, packing the uterus, tamponading bleeding from the inside with balloon or condom catheter), and pharmacological (with oxytocin, ergotamine, misoprostol). Alongside these treatments, shock should be addressed with IV fluids or blood transfusions as discussed below.

After delivery of the baby and placenta, the uterus should contract to close off blood vessels in the uterine wall that were attached to the placenta. If the uterus is not contracting (atonic uterus) or ruptures during delivery, severe bleeding can occur. Massaging the lower abdomen (fundal massage) increases contraction of the uterus and can be used preventatively to manage postpartum bleeding. Uterine bleeding can also occur if parts of the placenta or fetal tissue remain stuck in the uterus after delivery. While waiting to transfer, the placenta can be delivered with gentle massages of the uterus through the lower abdominal wall.[29] When the placenta is delivered, steady traction is applied to the cord as it is pulled out to prevent trauma, cord avulsion (tearing of the umbilical cord), uterine inversion, and retained placental products, all of which can increase blood loss and/or the risk of infection.

Severe blood loss leading to shock

When a woman is in shock she may have cold clammy skin, pale skin (especially around eyes, mouth, and hands), sweating, anxiousness, and loss of consciousness. She may have a fast heartbeat (110 beats per minute or more), low blood pressure (90mmHg systolic or less), and decreased urine output. The mother should be laid on her left side, with legs and buttocks elevated to encourage blood flow back to the heart with gravity. Most importantly, seek medical attention.[citation needed]

Seizures

Seizures related to pregnancy may be caused by eclampsia, which typically progresses from preeclampsia, a condition in pregnant women that is characterized by new-onset high blood pressure and protein in urine from kidney failure. Associated symptoms include headaches, blurry vision, trouble breathing from fluid in lungs, elevated liver enzymes from liver dysfunction, and possibly coagulation defects from platelet dysfunction.[citation needed]

If a pregnant woman begins to have seizures, additional help and assistance should be sought. One should not restrain the mother, but lie her down on her left side and check the airway (mouth, nose, throat). Turning the mother on her side decreases risk of breathing in vomit and spit. In a medical setting, magnesium sulfate is the preferred treatment for seizures in pregnant women.[citation needed]

Newborn care

Almost 10% of newborns require some resuscitative care. Common complications of childbirth that relate to the baby include breech presentation, shoulder dystocia, infection, and umbilical cord wrapped around the baby's neck (nuchal cord).

Evaluation

The newborn is evaluated at 1 and 5 minutes after birth using the Apgar score, which assigns points based on appearance (color), pulse, grimace (cry), activity (muscle tone), and respiration (breathing effort), with each component scored from 0 to 2. A healthy baby at birth usually has an Apgar score of 8 or 9. This means they look pink (indicating good oxygen flow) and have a heart rate greater than 100 bpm, a strong cry, and good muscle tone (i.e. is not limp). Scores below 7 generally require further care (see resuscitation below).

Routine care

After initial evaluation, babies with good Apgar scores are dried and rubbed, any obstruction of breathing is cleared, and they are warmed either with skin-to-skin contact with the mother or under a heat source.[citation needed]

Complications in the newborn

Neonatal complications can happen. In the United States home births, umbilical cord wrapped around the head happens 12-37% of the time (nuchal cord). Insufficient oxygenation (birth asphyxia) presents 9% of the time. 6% present with pulselessness and 3% have breech presentation.[30]

Breech presentation

Normally, the head is the first part of the body to present out of the birth canal. However, other parts such as the buttocks or feet can present first, which is referred to as breech presentation. Risk for breech presentation may increase with multiple pregnancies (more than one baby), when there is too little or too much fluid in the uterus, or if the uterus is abnormally shaped.[25] Babies in breech presentation can be delivered vaginally depending on the experience of the provider and if the fetus meets specific low risk criteria, however C-section is recommended if available.[31] Ideally, the fetus can be turned to the right position with maneuvers on the abdomen of the mother. This is called external cephalic version and it is a way to avoid Cesarean surgery and its possible risks. The maneuver cannot be performed on every woman. Contraindications to attempting to turn the baby with external cephalic version include oligohydramnios (when there is not enough amniotic fluid surrounding the baby), growth restrictions, or some abnormalities of the uterus.[32]

Vaginal delivery of a baby in breech position should not be performed without the availability of nearby emergency C-section capabilities and extensive efforts should be made to bring a woman in labor with breech presentation to a hospital. There are many variations of breech presentations and multiple ways the baby can get stuck during delivery. If a breech delivery is occurring, the provider will guide the hips out by giving light, downward traction holding the pelvis until the scapula is present. Then at the level of the armpits, each shoulder is delivered by rotating the baby as required, then subsequently rotating 180 degrees to deliver the other shoulder. The head is delivered with careful attention to the baby's arms. The arms will be delivered downwards through the vulva and may have to be gently held downwards by the provider's fingers.[21] It is important to note that when the infant in breech position has been delivered to the point in which the umbilical cord is seen but not the baby's head, the head has to be delivered within 8 to 10 minutes, or the baby will suffocate. This is because the umbilical cord provides oxygen to the baby from the mother, and if it is pressed in the birth canal, blood cannot pass to the baby to deliver oxygen.[29]

Pre-term labor

Incidence of preterm delivery is approximately 12%, and preterm births are a significant contributing cause of unplanned emergency delivery.[10] Pre-term labor is defined as occurring before 37 weeks, and risks for pre-term labor include pregnancy with multiple fetuses, prior history of premature labor, structural abnormalities of the cervix or uterus, urinary tract, vaginal, or sexually transmitted infections, high blood pressure, drug use, diabetes, blood disorders, or pregnancy occurring less than 6 months after a prior pregnancy.[21] The same principles of term emergency delivery apply to emergency delivery for a preterm fetus, though the baby will be at higher risk of other problems such as low birth weight, trouble breathing, and infections. The newborn will need additional medical care and monitoring after delivery and should be taken to a hospital providing neonatal care, which may include antibiotics and breathing treatments.[33]

Shoulder dystocia

In shoulder dystocia, the shoulder is trapped after the head is delivered, preventing delivery of the rest of the baby. The major risk factor (other than prior history of shoulder dystocia) is the baby being too large (macrosomia), which can result from the mother being obese or gaining too much weight, diabetes, and the pregnancy lasting too long (post-term pregnancy).[25] Shoulder dystocia can lead to further fetal complications such as nerve compression and injury at the shoulder (brachial plexus), fracture of the collarbone, and low oxygen for the fetus (whether due to compression of the umbilical cord or due to inability of the baby to breathe). Shoulder dystocia is often signaled by retreat of the head between contractions when it has already been delivered ("turtle sign"). Treatment includes the McRoberts maneuver, where the mother flexes her thighs up to her stomach with her knees wide apart as pressure is applied on her lower abdomen, and Wood's screw maneuver, where the deliverer inserts a hand into the vagina to rotate the fetus.[34] If all maneuvers fail, then C-section would be indicated.

Prolapsed cord

A prolapsed cord refers to an umbilical cord that is delivered from the uterus while the baby is still in the uterus and is life-threatening to the baby. Cord prolapse creates a risk of decreased blood flow (and oxygen flow) to the baby as delivery will cause cord compression. However, if the cord delivers before the baby, the cord should not be placed back into the uterus through the cervix since this increases risk of infection.[35] Emergent obstetric care for C-section would be indicated, and in the meantime, one should elevate the foot of the bed if possible to attempt to keep the baby above the level of the cord.[10] If no specialized care is available, one may attempt to reduce pressure of the cord manually and continue delivery, but this is often difficult to do.

Nuchal cord

After the baby crowns, the umbilical cord may be found to be wrapped around the neck or body of the baby, which is known as nuchal cord. This is common, occurring in up to 37% of term pregnancies, and most do not cause any long-term problems.[36] This wrapped cord should be slipped over the head so it is not pulled during delivery. If the wrap is not removed, it can choke the baby or can cause the placenta to detach suddenly which can cause severe uterine bleeding and loss of blood and oxygen supply to the baby. The cord may also be wrapped around a limb in breech presentation, and should similarly be reduced in these cases.

Resuscitation

If the baby is not doing well on its own, further care may be necessary. Resuscitation typically starts with warming, drying, and stimulating the newborn. If breathing difficulty is noted, the airway is opened and cleared with suction and oxygen is monitored; if necessary, one may consider using a positive airway pressure ventilator (which gives oxygen while keeping the airway open) or intubation. If the heart rate is below 60 beats per minute, CPR is started at 3:1 compression to ventilation ratio, with compressions given at the lower breastbone. If this fails to revive the newborn, epinephrine will be given.[10]

Resuscitation is not indicated for newborns below 22 weeks of gestation and weighing below 400 grams. Resuscitation may also be discontinued if the baby's heart does not start after 10–15 minutes of full resuscitation (including breathing treatments, medications, and CPR).

In culture

The reports of emergency childbirth are typically of general interest. They are frequently portrayed in dramatic scenes of movies and telenovelas.[citation needed]

A mobile app was developed in Ethiopia that guides users through the procedures of assisting with an emergency birth.[37]

References

- ^ Girsen, A. I.; Mayo, J. A.; Lyell, D. J.; Blumenfeld, Y. J.; Stevenson, D. K.; El-Sayed, Y. Y.; Shaw, G. M.; Druzin, M. L. (January 2018). "Out-of-hospital births in California 1991–2011". Journal of Perinatology. 38 (1): 41–45. doi:10.1038/jp.2017.156. ISSN 1476-5543. PMID 29120453. S2CID 39573399.

- ^ Nguyen, M. -L.; Lefèvre, P.; Dreyfus, M. (2016-01-01). "Conséquences maternelles et néonatales des accouchements inopinés extrahospitaliers". Journal de Gynécologie Obstétrique et Biologie de la Reproduction (in French). 45 (1): 86–91. doi:10.1016/j.jgyn.2015.02.002. ISSN 0368-2315. PMID 25818113.

- ^ MacDorman, Marian F.; Matthews, T. J.; Declercq, Eugene (March 2014). "Trends in out-of-hospital births in the United States, 1990-2012". NCHS Data Brief (144): 1–8. ISSN 1941-4927. PMID 24594003.

- ^ "Emergency Childbirth: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia Image". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ a b Javaudin, François; Hamel, Valérie; Legrand, Arnaud; Goddet, Sybille; Templier, François; Potiron, Christine; Pes, Philippe; Bagou, Gilles; Montassier, Emmanuel (2019-03-02). "Unplanned out-of-hospital birth and risk factors of adverse perinatal outcome: findings from a prospective cohort". Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine. 27 (1): 26. doi:10.1186/s13049-019-0600-z. ISSN 1757-7241. PMC 6397745. PMID 30825876.

- ^ "Emergency delivery: What to do when the baby's coming – right now | Your Pregnancy Matters | UT Southwestern Medical Center". utswmed.org. Retrieved 2022-09-13.

- ^ Reese, Phillip (2021-09-22). "Home Births Gain Popularity in 'Baby Bust' Decade". Kaiser Health News. Retrieved 2022-09-13.

- ^ "Births: Provisional Data for 2020" (PDF). May 2021.

- ^ MacDorman, Marian F.; Matthews, T. J.; Declercq, Eugene (March 2014). "Trends in out-of-hospital births in the United States, 1990-2012". NCHS Data Brief (144): 1–8. ISSN 1941-4927. PMID 24594003.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Frasure, Sarah Elisabeth (2016). "Emergency Delivery". In Tintinalli, Judith E.; Stapczynski, J. Stephan; Ma, O. John; Yealy, Donald M.; Meckler, Garth D.; Cline, David M. (eds.). Tintinalli's Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide (8 ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education.

- ^ a b Holmer, H; Oyerinde, K; Meara, Jg; Gillies, R; Liljestrand, J; Hagander, L (2015-01-01). "The global met need for emergency obstetric care: a systematic review". BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 122 (2): 183–189. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.13230. ISSN 1471-0528. PMID 25546039. S2CID 25934089.

- ^ Javaudin, François; Hamel, Valérie; Legrand, Arnaud; Goddet, Sybille; Templier, François; Potiron, Christine; Pes, Philippe; Bagou, Gilles; Montassier, Emmanuel (2019-03-02). "Unplanned out-of-hospital birth and risk factors of adverse perinatal outcome: findings from a prospective cohort". Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine. 27 (1): 26. doi:10.1186/s13049-019-0600-z. ISSN 1757-7241. PMC 6397745. PMID 30825876.

- ^ "Maternal mortality". www.who.int. Retrieved 2022-09-15.

- ^ a b Yevich, Steve (2001). Special Operations Forces Medical Handbook. US Government. pp. 3–87.

- ^ Archie, Carol L.; Roman, Ashley S. (2013), DeCherney, Alan H.; Nathan, Lauren; Laufer, Neri; Roman, Ashley S. (eds.), "Chapter 7. Normal & Abnormal Labor & Delivery", CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment: Obstetrics & Gynecology (11 ed.), New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies

- ^ a b "Information for Pregnant Women-What You Can Do". emergency.cdc.gov. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ a b Publications, Harvard Health (September 2005). "Emergencies and First Aid - Childbirth - Harvard Health". Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Iserson, Kenneth (2016). Improvised Medicine: Providing Care in Extreme Environments, 2e. McGraw-Hill Education. pp. Chapter 31. ISBN 978-0-07-184762-9.

- ^ a b c d "Precipitous birth not occurring on a labor and delivery unit". uptodate.com. Retrieved 2017-11-26.

- ^ Blouse, Ann; Gomez, Patricia (2003). Emergency Obstetric Care (PDF). United States Agency forvInternational Development.

- ^ a b c d e f Cunningham, F. Gary (2013). "Williams Obstetrics, Twenty-Fourth Edition". Retrieved 2017-12-01.

- ^ a b c Sharp, Brian; Sharp, Kristen; Wei, Eric (2017), Borhart, Joelle (ed.), "Precipitous Labor and Emergency Department Delivery", Emergency Department Management of Obstetric Complications, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 75–89, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-54410-6_7, ISBN 978-3-319-54410-6, retrieved 2022-09-15

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Carol, Archie (2013). CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment: Obstetrics & Gynecology, 11e. The McGraw-Hill Companies. pp. chapter 7. ISBN 978-0-07-163856-2.

- ^ Cunningham, F. Gary (2018). "Normal Labor". Williams Obstetrics (25th ed.). McGraw Hill.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Cunningham, F; et al. (2014). Williams Obstetrics, Twenty-Fourth Edition. McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-0-07-179893-8.

- ^ "Bleeding and spotting from the vagina during pregnancy". www.marchofdimes.org. Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ^ Mouri, MIchelle; Hall, Heather; Rupp, Timothy J. (2022), "Threatened Abortion", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 28613498, retrieved 2022-09-14

- ^ "UpToDate". www.uptodate.com. Retrieved 2022-09-14.

- ^ a b White, Gregory (2002). Emergency Childbirth: A Manual (PDF). NAPSAC. p. 22.

- ^ "Obstetrics/Gynecology." 'Improvised Medicine: Providing Care in Extreme Environments, 2e' Ed. Kenneth V. Iserson. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, http://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com.ucsf.idm.oclc.org/content.aspx?bookid=1728§ionid=115697898.

- ^ "Mode of Term Singleton Breech Delivery - ACOG". acog.org. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- ^ Rosman, Ageeth N.; Guijt, Aline; Vlemmix, Floortje; Rijnders, Marlies; Mol, Ben W. J.; Kok, Marjolein (February 2013). "Contraindications for external cephalic version in breech position at term: a systematic review: Contraindications for ECV". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 92 (2): 137–142. doi:10.1111/aogs.12011. PMID 22994660. S2CID 43311187.

- ^ "Preterm Labor - Gynecology and Obstetrics - Merck Manuals Professional Edition". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- ^ "Fetal Dystocia - Gynecology and Obstetrics - Merck Manuals Professional Edition". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- ^ Kahana, B; Sheiner, E; Levy, A; Lazer, S; Mazor, M (2004). "Umbilical cord prolapse and perinatal outcomes". Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 84 (2): 127–32. doi:10.1016/S0020-7292(03)00333-3. PMID 14871514. S2CID 31686188.

- ^ Peesay, Morarji (2012-08-28). "Cord around the neck syndrome". BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 12 (Suppl 1): A6. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-12-S1-A6. ISSN 1471-2393. PMC 3428673.

- ^ Kuo, Lily (12 November 2015). "A mobile app could make childbirth safer in Ethiopia, one of the deadliest countries to have a baby". Retrieved 3 August 2017.