Western pond turtle

| Western pond turtle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Superfamily: | Testudinoidea |

| Family: | Emydidae |

| Genus: | Actinemys |

| Species: | A. marmorata[1]

|

| Binomial name | |

| Actinemys marmorata[1] | |

| |

| The range of the western pond turtle. | |

| Synonyms[4] | |

The western pond turtle (Actinemys marmorata), also known commonly as the Pacific pond turtle is a species of small to medium-sized turtle in the family Emydidae. The species is endemic to the western coast of the United States and Mexico, ranging from western Washington state to northern Baja California. It was formerly found in Canada (in British Columbia), but in May 2002, the Canadian Species at Risk Act listed the Pacific pond turtle as being extirpated.

Taxonomy and systematics

Its genus classification is mixed. Emys and Actinemys were used among published sources in 2010.[5] It was known by several names in the Indigenous languages of its range, including kʰá:wanaka: (Northeastern Pomo), kʰa:wana (Southern Pomo), and ʔaləšək (Lushootseed).

Description

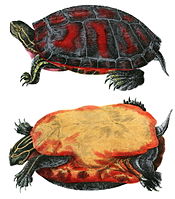

The dorsal color of A. marmorata is usually dark brown or dull olive, with or without darker reticulations or streaking. The plastron is yellowish, sometimes with dark blotches in the centers of the scutes. The straight carapace length is 11–21 cm (4.5–8.5 in). The carapace is low and broad, usually widest behind the middle, and in adults is smooth, lacking a keel or serrations. Adult western pond turtles are sexually dimorphic, with males having a light or pale yellow throat.

Distribution

The western pond turtle originally ranged from northern Baja California, Mexico, north to the southern regions of British Columbia, Canada. It was once a large part of a major fishery on Tulare Lake, California, supplying San Francisco with a local favorite, turtle soup, as well as feed for hogs that learned to dive for it in the shallows of Hog Island, also on Tulare Lake.[citation needed] As of 2007, it has become rare or absent in the Puget Sound region of Washington. It has a disjunct distribution in most of the Northwest, and some isolated populations exist in southern Washington. The western pond turtle is now rare in the Willamette Valley north of Eugene, Oregon, but abundance increases south of that city where temperatures are higher. It may be locally common in some streams, rivers and ponds in southern Oregon. A few records are reported east of the Cascade Mountains, but these may have been based on introduced individuals. It ranges up to 305 m (1,001 ft) in Washington, and to about 915 m (3,002 ft) in Oregon. It also occurs in Uvas Canyon area, Santa Cruz Mountains, California, and in the North Bay, and lakes such as Fountaingrove Lake. Many taxonomic authorities now split what had been considered one species of turtle into two species. The southern species is named Actinemys pallida, or the southwestern pond turtle. Its range is southern California and Mexico. The northern species remains Actinemys marmorata, with a range of northern California northward. It is then usually referred to as the northwestern pond turtle.

Ecology and behavior

The western pond turtle occurs in both permanent and intermittent waters, including marshes, streams, rivers, ponds, and lakes. It favors habitats with large numbers of emergent logs or boulders, where individuals aggregate to bask. They also bask on top of aquatic vegetation. Consequently, this species is often overlooked in the wild. However, it is possible to observe resident turtles by moving slowly and hiding behind shrubs and trees.

A. marmorata can be encouraged to use artificial basking substrate, or rafts, which allows for easy detection of the species in complex habitats.

In addition to its aquatic habitat, terrestrial habitat is also extremely important for the western pond turtle. Since many intermittent ponds can dry up during summer and fall months along the west coast, especially during times of drought, the western pond turtle can spend upwards of 200 days out of water. Many turtles overwinter outside of the water, during which time they often create their nests for the year.

Diet

The western pond turtle is omnivorous and most of its animal diet includes insects, crayfish, and other aquatic invertebrates. Fish, tadpoles, and frogs are eaten occasionally, and carrion is eaten when available. Plant foods include filamentous algae, lily pads, tule and cattail roots. Juveniles are primarily carnivorous, and eat insects and carrion. At about age three they begin to eat plant matter.

Predation and threat

Raccoons, otters, ospreys, and coyotes are the biggest natural threats to this turtle, its eggs, and hatchlings. Weasels and large fish are also known predators.,[6] Non-native predators include bullfrogs, crayfish, and opossums.

In the past the turtle was exploited as food by both indigenous peoples and American settlers. After the goldrush in California a large "fishery" emerged processing turtles from the San Francisco Bay Estuary into canned soup for markets East.

Finally, this species is still threatened by humankind. Due to habitat destruction and modification, this species is currently listed as vulnerable on the IUCN Red List and by NatureServe. It also faces significant competition from introduced invasive species, especially the red-eared slider. With the removal of ponds, modification of sandy banks needed for egg laying, draining of wetlands, this species is now vulnerable. Efforts at reintroducing this turtle to its native range have met with limited success.

Reproduction

Sexually mature females of the western pond turtle produce 5–13 eggs per clutch. They deposit eggs either once or twice a year. They may travel some distance from water for egg-laying, moving as much as 0.8 km (1/2 mile) away from and up to 90 m (300 ft) above the nearest source of water, but most nests are within 90 m (300 ft) of water. The female usually leaves the water in the evening and may wander far before selecting a nest site, often in an open area of sand or hardpan that is facing southwards. The nest is flask-shaped with an opening of about 5 cm (2 in). Females spend considerable time covering up the nest with soil and adjacent low vegetation, making it difficult for a person to find unless it has been disturbed by a predator.

Hatchlings

The vast majority of western pond turtle hatchlings overwinter in the nest, and this phenomenon seems prevalent in most parts of the range, especially northern areas. This might explain the difficulty researchers have had in trying to locate hatchlings in the fall months. Winter rains may be necessary to loosen the hardpan soil where some nests are deposited. It may be that the nest is the safest place for hatchlings to shelter while they await the return of warm weather. Whether it is hatchlings or eggs that overwinter, young first appear in the spring following the year of egg deposition. Individuals grow slowly in the wild, and their age at their first reproduction may be 10 to 12 years in the northern part of the range. The western pond turtle may survive more than 50 years in the wild.

References

- ^ Rhodin 2010, p. 000.105

- ^ Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group (1996). "Actinemys marmorata". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1996: e.T4969A97292542. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1996.RLTS.T4969A11104202.en.

- ^ "Actinemys marmorata. NatureServe Explorer 2.0". explorer.natureserve.org. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- ^ Species Actinemys marmorata at The Reptile Database . www.reptile-database.org.

- ^ Rhodin 2010, p. 000.139

- ^ "Wildscreen Arkive". arkive.org. Archived from the original on 23 January 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

Bibliography

- Holland, Dan C., PhD. The Western Pond Turtle: Habitat and History, Final Report. U.S. Department of Energy, Bonneville Power Administration, Division of Fish and Wildlife; Wildlife Diversity Program, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, August 1994.

- Rhodin, Anders G.J.; van Dijk, Peter Paul; Iverson, John B.; Shaffer, H. Bradley (2010-12-14). "Turtles of the World 2010 Update: Annotated Checklist of Taxonomy, Synonymy, Distribution and Conservation Status" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-07-17. Retrieved 2010-12-15.

- "Western pond turtle (Actinemys marmorata)". Wildscreen ARKive. Archived from the original on 1 February 2019. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

Further reading

- Baird SF, Girard CF (1852). "Descriptions of new species of Reptiles, collected by the U. S. Exploring Expedition under the command of Capt. Charles Wilkes, U. S. N. First part.—Including the species from the Western coast of America". Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. Philadelphia 6: 174–177. (Emys marmorata, new species, p. 177).

- Seidel, Michael E.; Ernst, Carl H. (2017). "A Systematic Review of the Turtle Family Emydidae". Vertebrate Zoology 67 (1): 1–122. (Actinemys marmorata, pp. 36–38, Figure 36).

- IUCN Red List vulnerable species

- NatureServe vulnerable species

- Emys

- Actinemys

- Turtles of North America

- Reptiles of Mexico

- Reptiles of the United States

- Fauna of the Western United States

- Fauna of the San Francisco Bay Area

- Reptiles described in 1852

- Taxa named by Spencer Fullerton Baird

- Taxa named by Charles Frédéric Girard