Colombians

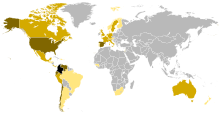

Map of the Colombian Diaspora in the World | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 57 million (2022 estimate) Diaspora c. 5 million 0.8% of world's population | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 1,606,238[2] | |

| 721,791[3] | |

| 566,214[4] | |

| 173,804 (2021)[5] | |

| 89,931[6] | |

| 76,580[7] | |

| 41,885[8] | |

| 39,540[9] | |

| 39,066[10] | |

| 36,234[11] | |

| 28,015[12] | |

| 27,714[13] | |

| 20,705[14] | |

| 20,515[15] | |

| 19,848[16] | |

| 14,722[17] | |

| 13,411[18] | |

| Languages | |

| Primarily Colombian Spanish and Indigenous Languages, as well as other minority languages | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Roman Catholic;[19] Protestant minority See Religion in Colombia | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Latin Americans | |

Colombians (Template:Lang-es) are people identified with the country of Colombia. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Colombians, several (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of their being Colombian.

Colombia is considered to be one of the most multiethnic societies in the world, home to people of various ethnic, religious and national origins. Many Colombians have varying degrees of European, Indigenous, African, Arab and Asian ancestry.[20]

The majority of the Colombian population is made up of immigrants from the Old World and their descendants, mixed in part with the original populations, especially Iberians and to a lesser extent other Europeans.[21] Following the initial period of Spanish conquest and immigration, different waves of immigration and settlement of non-indigenous peoples took place over the course of nearly six centuries and continue today. Elements of Native American and more recent immigrant customs, languages and religions have combined to form the culture of Colombia and thus a modern Colombian identity.[22]

Ethnic groups

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2021) |

European Colombians

Most part of Colombia's population descends from European immigration in the mid 16th to late 20th centuries. Approximately 70% of the Colombian population, or 40 million Colombians, can trace back their ancestry to the various European immigrant groups that arrived in Colombia, primarily in the 19th and 20th centuries.

The greatest waves of European immigration to Colombia can generally be divided into three time periods: the 1820s-1850's, which brought hundreds of immigrants mainly from Spain, Italy, Germany (including Ashkenazi Jewish); the 1880s-to 1910s, which brought many immigrants from France, Portugal, Belgium, Astro-Hungary, Denmark, Croatia, and Switzerland; and the 1920s-1960s, the last great wave of European immigration to Colombia, which brought many British (including Irish) immigrants, as well as other European groups such as the Dutch, Polish, Russian, Scandinavian, and other Eastern European immigrants who primarily settled in Colombia's great urban centers. These immigrants came to Colombia attracted by the country's growing population and business opportunities. In addition to these waves of immigration, a great number of Jews fled to Colombia during and after the Second World War, seeking to escape violence in Europe. Immigrants mostly to the Caribbean and Andean regions.[23][24][25][26][27] There are smaller numbers of Dutch, Swiss, Austrians, Danish, Norwegian, Portuguese, Belgian, Russian, Polish, Hungarian, Bulgarian, Lithuanian, Ukrainian, Czech, Greek and Croatian communities that immigrated during the Second World War and the Cold War.[28][29][30]

Mestizo Colombians

Estimates of the Mestizo or Mixed population in Colombia vary, as Colombia's national census does not distinguish between White and Mestizo Colombians. According to the 2018 census, the Mestizo and White population combined make up approximately 87% of the Colombian population, while an estimated 20% of Colombians are Mestizo or mixed race.[31] A genetic study by the University of Brasilia estimates that the average admixture for Mestizo Colombians is 45.9% European, 33.8% Amerindian, and 20.3% African ancestry, however this varies significantly across region. [32]

Native American Colombians

Originally, Colombia's territory was inhabited entirely by Amerindian groups. Colombia's indigenous cultures evolved from three main groups—the Quimbayas, who inhabited the western slopes of the Cordillera Central; the Chibchas; and the Kalina (Caribs). The Muisca culture, a subset of the larger Chibcha ethnic group and famous for their use of gold, were responsible for the legend of El Dorado. Today Native American people comprise roughly 4.4% of the population in Colombia.[33] More than fifty different indigenous ethnic groups inhabit Colombia. Most of them speak languages belonging to the Chibchan and Cariban language families.[citation needed]

Historically there are 567 reserves (resguardos) established for Native American peoples and they are inhabited by more than 800,000 people. The 1991 constitution established that their native languages are official in their territories, and most of them have bilingual education systems teaching both native languages and Spanish. Some of the largest indigenous groups are the Wayuu,[34] the Zenú, the Pastos, the Embera and the Páez. The departments (departamentos) with the biggest indigenous population are Cauca, La Guajira, Nariño, Cordoba and Sucre.[33]

Asian Colombians

Colombia's Asian community is generally made up of people of West Asian descent, particularly the Lebanese, Syrian, and Palestinian, though there are also smaller communities of East Asian, South Asian and Southeast Asian ancestry. West Asians, particularly Levantine immigrants from the Ottoman Empire came in the late 19th and 20th centuries. In 1928, several Japanese families settled in Valle del Cauca where they came as farmers to grow crops. Between 1970 and 1980, it was estimated that there were more than 6,000 Chinese immigrants in Colombia.[citation needed] In 2014, it was estimated that there were 25,000 Chinese living in Colombia.[35] Their current communities are found in Bogotá, Barranquilla, Cali, Cartagena, Medellín, Santa Marta, Manizales, Cucutá and Pereira. There are additional Asian populations that immigrated to Colombia in smaller numbers, such as Iranians, Indians, Koreans, Filipinos and Pakistanis.

West Asian Colombians

Many Colombians have origins in the Western Asian countries of Lebanon, Jordan, Syria and Palestine, It is estimated that Arab Colombians represent 3.2 million people.[36] Many moved to Colombia to escape the repression of the Turkish Ottoman Empire and/or financial hardships. When they were first processed in Colombia's ports, they were classified as "Turks". It is estimated that Colombia has a Lebanese population of 700,000 direct descendants and 1,500,000 who have partial ancestry. Meanwhile, the Palestine population is estimated between 100,000 and 120,000.[37] Most Syrian-Lebanese immigrants established themselves in the Caribbean Region of Colombia in the towns of Santa Marta, Santa Cruz de Lorica, Fundación, Aracataca, Ayapel, Calamar, Ciénaga, Cereté, Montería and Barranquilla near the basin of the Magdalena River, in La Guajira Department, notably in Maicao and in the Archipelago of San Andrés, Providencia and Santa Catalina. Many Arab-Colombians adapted their names and surnames to the Spanish language to assimilate more quickly in their communities. Some Colombian surnames of Arab origin include: Guerra (originally Harb), Domínguez (Ñeca), Durán (Doura), Lara (Larach), Cristo (Salibe), among other surnames.

There are about 8,000 Colombians of Jewish origin who practice Judaism, most of them live in Bogotá. Colombia's Jewish community includes Sephardi Jews from countries such as Syria and Turkey also immigrated to the country and run their independent religious organizations. The Confederación de Comunidades Judías de Colombia coordinates Jews and institutions that practice the religion.

Consequently, there were other immigrants from the Western Asia, including a number of Armenian, Turkish, Georgian and Cypriot immigrants who arrived in the country during the early 20th century.

Afro-Colombians

Also known as "Afro", or "Afro-colombianos" (in Spanish). According to the 2018 census, they are 5.34% of country population,[38][39] while genetic studies have obtained between 6.6% [40] 9.2 [41] and 11%[21] of African DNA in the Colombian population. Also the % and numbers of Afro Colombians can vary depending on the region, being the majority population in the Pacific Region, frequently found in the Caribbean Region but a minority in the Andean Region, Orinoquia Region and Amazon Region.[42][43] Colombia has the fourth-largest African diaspora on the planet after the USA, Brazil and Haiti.[44][45]

Immigrant groups

Because of its strategic location Colombia has received several immigration waves during its history. Most of these immigrants have settled in the Caribbean Coast; Barranquilla (the largest city in the Colombian Caribbean Coast) and other Caribbean cities have the largest population of Lebanese, German, British, French, Italian, Irish and Romani descendants. There are also important communities of American and Chinese descendants in the Andean Region and Caribbean Coast especially in Medellin, Bogota, Cali, Barranquilla and Cartagena. Most immigrants are Venezuelans, they are evenly distributed throughout the country.[46]

Languages

There are 101 languages listed for Colombia in the Ethnologue database, of which 80 are spoken today as living languages. There are currently about 850,000 speakers of native languages.[47][48]

Education

The educational experience of many Colombian children begins with attendance at a preschool academy until age five (Educación preescolar). Basic education (Educación básica) is compulsory by law.[49] It has two stages: Primary basic education (Educación básica primaria) which goes from first to fifth grade – children from six to ten years old, and Secondary basic education (Educación básica secundaria), which goes from sixth to ninth grade. Basic education is followed by Middle vocational education (Educación media vocacional) that comprises the tenth and eleventh grades. It may have different vocational training modalities or specialties (academic, technical, business, and so on.) according to the curriculum adopted by each school.

After the successful completion of all the basic and middle education years, a high-school diploma is awarded. The high-school graduate is known as a bachiller, because secondary basic school and middle education are traditionally considered together as a unit called bachillerato (sixth to eleventh grade). Students in their final year of middle education take the ICFES test (now renamed Saber 11) in order to gain access to higher education (Educación superior). This higher education includes undergraduate professional studies, technical, technological and intermediate professional education, and post-graduate studies.

Bachilleres (high-school graduates) may enter into a professional undergraduate career program offered by a university; these programs last up to five years (or less for technical, technological and intermediate professional education, and post-graduate studies), even as much to six to seven years for some careers, such as medicine. In Colombia, there is not an institution such as college; students go directly into a career program at a university or any other educational institution to obtain a professional, technical or technological title. Once graduated from the university, people are granted a (professional, technical or technological) diploma and licensed (if required) to practice the career they have chosen. For some professional career programs, students are required to take the Saber-Pro test, in their final year of undergraduate academic education.[50]

Public spending on education as a proportion of gross domestic product in 2012 was 4.4%. This represented 15.8% of total government expenditure. In 2012, the primary and secondary gross enrolment ratios stood at 106.9% and 92.8% respectively. School-life expectancy was 13.2 years. A total of 93.6% of the population aged 15 and older were recorded as literate, including 98.2% of those aged 15–24.[51]

Religion

The National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE) does not collect religious statistics, and accurate reports are difficult to obtain. However, based on various studies and a survey, about 90% of the population adheres to Christianity, the majority of which (70.9%) are Roman Catholic, while a significant minority (16.7%) adhere to Protestantism (primarily Evangelicalism)[citation needed]. Some 4.7% of the population is atheist or agnostic, while 3.5% claim to believe in God but do not follow a specific religion. 1.8% of Colombians adhere to Jehovah's Witnesses and Adventism and less than 1% adhere to other religions, such as Islam, Judaism, Buddhism, Mormonism, Hinduism, Indigenous religions, Hare Krishna movement, Rastafari movement, Eastern Orthodox Church, and spiritual studies. The remaining people either did not respond or replied that they did not know. In addition to the above statistics, 35.9% of Colombians reported that they did not practice their faith actively.[52][53][54]

While Colombia remains a mostly Roman Catholic country by baptism numbers, the 1991 Colombian constitution guarantees freedom and equality of religion.[55]

See also

- List of Colombians

- Colombian diaspora

- Culture of Colombia

- Colombia in Popular Culture

- Colombian Americans

- Colombian Canadians

- Colombian Mexicans

- Colombians in Spain

- Colombians in Uruguay

- Hispanics

References

- ^ "Proyecciones de Población DANE". National Administrative Department of Statistics (Colombia). Retrieved 10 November 2022.

- ^ "Colombian Immigrants in the United States". Migration Policy Institute. 11 July 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ INE (2011). "Población nacida en el exterior, por año llegada a Venezuela, según país de nacimiento, Censo 2011" (PDF). Ine.gob.ve (in Spanish).

- ^ Población (españoles/extranjeros) por país de nacimiento y sexo INE

- ^ "Estimación población extranjera en Chile 2021". INE. Retrieved 11 October 2023.

- ^ "Internal immigration" (PDF). dspace.espol.edu.ec. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

- ^ Statistics Canada (2011). "2011 National Household Survey: Data tables". 12.statcan.gc.ca.

- ^ "Población nacida en el extranjero en la República, por grupos de edad, según sexo y país de nacimiento" (in Spanish). Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censo de Panamá.

- ^ "Table 5.1 Estimated resident population, by country of birth(a), Australia, as at 30 June, 1996 to 2020(b)(c)". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ "Table 1.3: Overseas-born population in the United Kingdom by country of birth and sex, January 2020 to December 2020". Office for National Statistics. 17 September 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2021. Figure given is the central estimate. See the source for 95% confidence intervals.

- ^ INEGI (2010). "Conociendo...nos Todos" (PDF) (in Spanish).

- ^ 385.899 extranjeros viven en Costa Rica La Nación

- ^ Estadisticas Radicaciones 2014 [Residencies 2014] (PDF) (in Spanish). Vol. 1. Buenos Aires: Ministry of Internal Affairs of Argentina. 2014. ISBN 978-950-896-420-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 June 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ^ "Anzahl der Ausländer in Deutschland nach Herkunftsland". De.statista.com (in German). Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ "CBS StatLine - Bevolking; generatie, geslacht, leeftijd en herkomstgroepering, 1 januari". Statline.cbs.nl. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ "Colombiani in Italia. Popolazione residente in Italia proveniente dalla Colombia al 1° gennaio 2021. Dati ISTAT". tuttitalia.it (in Italian). Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ "NAT1 - Population par sexe, âge et nationalité en 2018 − France métropolitaine −Étrangers - Immigrés en 2018 | Insee".

- ^ "Befolkning efter födelseland, ålder och kön. År 2000 - 2021" [Population by country of birth, gender and year: Year 2000 - 2021] (in Swedish). Statistics Sweden. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ "CIA – The World Factbook – Colombia". Cia.gov. Archived from the original on 30 May 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ Semana (12 August 2017). "El gran legado de los inmigrantes en Colombia". Semana.com Últimas Noticias de Colombia y el Mundo (in Spanish). Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ a b Ruiz-Linares, Andrés; Adhikari, Kaustubh; Acuña-Alonzo, Victor; Quinto-Sanchez, Mirsha; Jaramillo, Claudia; Arias, William; Fuentes, Macarena; Pizarro, María; Everardo, Paola; Avila, Francisco de; Gómez-Valdés, Jorge (25 September 2014). "Admixture in Latin America: Geographic Structure, Phenotypic Diversity and Self-Perception of Ancestry Based on 7,342 Individuals". PLOS Genetics. 10 (9): e1004572. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004572. ISSN 1553-7404. PMC 4177621. PMID 25254375.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "COLOMBIA UNA NACIÓN MULTICULTURAL" (PDF). DANE - El Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística (in Spanish). Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ "News & Events - Irlandeses en Colombia y Antioquia - Department of Foreign Affairs". www.dfa.ie. Retrieved 7 September 2022.

- ^ "Estos fueron los primeros alemanes en Colombia". Revista Diners | Revista Colombiana de Cultura y Estilo de Vida (in Spanish). 10 June 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ^ Vidal Ortega, Antonino; D’Amato Castillo, Giuseppe (1 December 2015). "Los otros, sin patria: italianos en el litoral Caribe de Colombia a comienzos del siglo XX". Caravelle. Cahiers du monde hispanique et luso-brésilien (in French) (105): 153–175. doi:10.4000/caravelle.1822. ISSN 1147-6753.

- ^ "Conozca a los inmigrantes europeos que se quedaron en Colombia". Revista Diners | Revista Colombiana de Cultura y Estilo de Vida (in Spanish). 2 July 2020. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ Salamanca, Helwar Figueroa; Espitia, Julián David Corredor (31 July 2019). ""En una ciudad gris y silenciosa": la migración francesa en Bogotá (1900-1920)". Anuario de Historia Regional y de las Fronteras (in Spanish). 24 (2): 75–100. doi:10.18273/revanu.v24n2-2019003. ISSN 2145-8499.

- ^ "Del este de Europa, al Sur de América: Migraciones Soviéticas y Post Soviéticas a la Ciudad de Bucaramanga, Santander" (PDF) (in Spanish). Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ^ "Inmigración lituana en Colombia. La migración de los lituanos a Colombia tuvo lugar por primera vez durante la década de 1940, cuando la mayoría de los ciudadan". ww.es.freejournal.org (in Spanish). Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ^ "Colombia y Europa Oriental en la serie documental Inmigrantes".

- ^ "Geoportal del DANE - Geovisor CNPV 2018". geoportal.dane.gov.co. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- ^ Godinho, Neide Maria de Oliveira (2008). O impacto das migrações na constituição genética de populações latino-americanas (Thesis).

- ^ a b "Poblacion Indigena de Columbia" (PDF). dane.gov.co. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

- ^ EPM (2005). "La etnia Wayuu". Empresas Publicas de Medellin (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 19 February 2008. Retrieved 29 February 2008.

- ^ Gómez, Diana A.; Díaz, Luz M.; Gómez, Diana A.; Díaz, Luz M. (June 2016). "Las organizaciones chinas en Colombia". Migración y desarrollo (in Spanish). 14 (26): 75–110. doi:10.35533/myd.1426.dag.lmd. ISSN 1870-7599.

- ^ S.A.S, Editorial La República. "Colombia y Medio Oriente". Diario La República (in Spanish). Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ Tiempo, Casa Editorial El (7 March 2019). "Los palestinos que encontraron un segundo hogar en el centro de Bogotá". El Tiempo (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ "La visibilización estadística de los grupos étnicos colombianos" (PDF) (in Spanish).

- ^ Colombia: People 2019, DANE

- ^ Mooney, Jazlyn A.; Huber, Christian D.; Service, Susan; Sul, Jae Hoon; Marsden, Clare D.; Zhang, Zhongyang; Sabatti, Chiara; Ruiz-Linares, Andrés; Bedoya, Gabriel; Freimer, Nelson; Lohmueller, Kirk E. (1 November 2018). "Understanding the Hidden Complexity of Latin American Population Isolates". American Journal of Human Genetics. 103 (5): 707–726. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.09.013. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 6218714. PMID 30401458.

- ^ Homburger, Julian R.; Moreno-Estrada, Andrés; Gignoux, Christopher R.; Nelson, Dominic; Sanchez, Elena; Ortiz-Tello, Patricia; Pons-Estel, Bernardo A.; Acevedo-Vasquez, Eduardo; Miranda, Pedro; Langefeld, Carl D.; Gravel, Simon (4 December 2015). "Genomic Insights into the Ancestry and Demographic History of South America". PLOS Genetics. 11 (12): e1005602. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005602. ISSN 1553-7390. PMC 4670080. PMID 26636962.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Afro-Colombians". Minority Rights Group. 19 June 2015. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ^ "lb1". ImgBB. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ^ Yelvington, Kevin A. (2005), Ember, Melvin; Ember, Carol R.; Skoggard, Ian (eds.), "African Diaspora in the Americas", Encyclopedia of Diasporas: Immigrant and Refugee Cultures Around the World, Boston, MA: Springer US, pp. 24–35, doi:10.1007/978-0-387-29904-4_3, ISBN 978-0-387-29904-4, retrieved 31 December 2022

- ^ Kale, Esmeralda. "Research Guides: African Diaspora in the Americas and the Caribbean: Resistance, Culture and Survival: Getting Started". libguides.northwestern.edu. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ^ "Aumenta El Numero De Inmigrantes Venezolanos En Colombia 017591". Ntn24.com. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- ^ "The Languages of Colombia". Ethnologue.com. Retrieved 16 May 2010.

- ^ "Native languages of Colombia" (in Spanish). lenguasdecolombia.gov.co. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ Colombian Constitution of 1991 (Title II - Concerning rights, guarantees, and duties - Chapter 2 - Concerning social, economic and cultural rights - Article 67)

- ^ "Ministerio de Educación de Colombia, Estructura del sistema educativo". 29 June 2007. Archived from the original on 29 June 2007.

- ^ "UNESCO Institute for Statistics Colombia Profile". Uis.unesco.org. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

- ^ Beltrán Cely, William Mauricio (2013). Del monopolio católico a la explosión pentecostal' (PDF) (in Spanish). Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Facultad de Ciencias Humanas, Centro de Estudios Sociales (CES), Maestría en Sociología. ISBN 978-958-761-465-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2016.

- ^ Beltrán Cely, William Mauricio. "Descripción cuantitativa de la pluralización religiosa en Colombia" (PDF). Universitas humanística 73 (2012): 201–238. – bdigital.unal.edu.co. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 March 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- ^ "Religion in Latin America, Widespread Change in a Historically Catholic Region". Pewforum.org. Pew Research Center. 13 November 2014.

- ^ Colombian Constitution of 1991 (Title II – Concerning rights, guarantees, and duties – Chapter I – Concerning fundamental rights – Article 19)