Documentary hypothesis

In studying the Hebrew Bible, some historians and academics in the fields of linguistics and source criticism have proposed the theory known as the documentary hypothesis: that the Five Books of Moses (the Torah) represent a combination of documents from different sources rather than a single text authored by one individual.

In general, the authorship of all the books of the Bible — perhaps with the exception of some of Paul's letters — remains very much an open topic of research: see higher criticism. Historians show interest in learning who wrote the books of the Bible and when; modern studies on this subject began in the 19th century, and they have constituted a lively field of activity ever since.

Assigning a solid date to any book of the Bible poses difficulties: see dating the Bible.

The hypothesis itself

Background to the hypothesis

Major areas considered by scholars supporting the documentary hypothesis include:

- The variations in the divine names in Genesis;

- The secondary variations in diction and in style;

- The parallel or duplicate accounts (doublets);

- The continuity of the various sources;

- The political assumptions implicit in the text;

- The interests of the author(s).

Many portions of the Torah seem to imply more than one author. Doublets and triplets repeat stories with different points of view. Notable repetitions include:

- the creation-accounts in Genesis. The creation-story in Genesis first describes a somewhat evolutionary process, starting with the creation of the Earth, then the lower forms of life, then animals, and finally man and woman (created together). It then begins the story again, but this time with the creation of man first, then animals to assuage man's loneliness, and when this fails, the creation of Eve from Adam's rib;

- in the flood story Noah takes his family into the ark twice;

- the stories of the covenant between God and Abraham;

- the naming of Isaac;

- the three strikingly similar narratives in Genesis about a wife confused for a sister;

- the two stories of the revelation to Jacob at Bet-El;

- three different versions of how the town of Be'ersheba got its name;

- Exodus 38:26 mentions "603,550 men over 20 years old included in the census" immediately after passage of the Red Sea, while Numbers 1:44-45 cites the precisely identical count, "The tally of Israelites according to their paternal families, those over 20 years old, all fit for service. The entire tally was 603,550", in a census taken a full year later, "on the first [day] of the second month in the second year of the Exodus" (Numbers 1:1);

- the story of the flood in Genesis appears to claim that two of all kinds of animal went on the ark, but also that seven of certain kinds went on, and that the flood lasted a year, but also lasted only 40 days;

- the Ten Commandments appear in Exod 20, but in a slightly different wording in Deut 5. A second, almost completely different set of Ten Commandments appears in Exod 34;

- Numbers 25 describes the rebellion at Peor and refers to daughters of Moab, but the same chapter portrays one woman as a Midianite;

- Moses' wife, though often identified as a Midianite (and hence Semitic), appears in the tale of Snow-white Miriam as a "Cushite" (Ethiopian), and hence black ;

- in some locations God appears friendly and capable of errors and regret, and walks the earth talking to humans, but in others God seems unmerciful and distant;

- a number of places or individuals have multiple names. For instance, some passages give the name of the mountain that Moses climbed to receive the commandments as Horeb and others as Sinai, Moses' father-in-law has at least two names in the Hebrew original (יֶתֶר, יִתְרוֹ, and רְעוּאֵל), etc.

However, classical rabbinical and other interpretations claim to have accounted for all of the above difficulties. Note also that Orthodox Judaism regards the Torah as all but impossible to understand without the insight of the Oral Torah. On the other hand, many supporters of the documentary hypothesis disagree and view these arguments as apologetic. See the section on #Debates on the hypothesis below.

The modern hypothesis

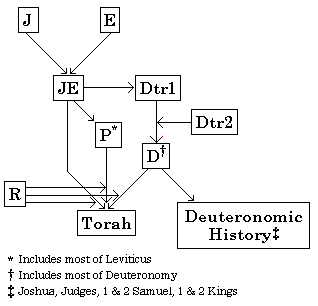

The hypothesis proposes that a redactor (referred to as R) composed the Torah by combining four earlier source texts (J, E, P and D), specifically:

- J - the Jahwist. J describes a human-like God called Yahweh and has a special interest in Judah and in the Aaronid priesthood. J has an extremely eloquent style. J uses an earlier form of the Hebrew language than P.

- E - the Elohist. E describes a human-like God initially called El (which sometimes appears as Elohim according to the rules of Hebrew grammar), and called Yahweh subsequent to the incident of the burning bush. E focuses on biblical Israel and on the Shiloh priesthood. E has a moderately eloquent style. E uses an earlier form of the Hebrew language than P.

- P - the Priestly source. P describes a distant and unmerciful God, sometimes referred to as Elohim or as El Shaddai. P partly duplicates J and E, but alters details to suit P's opinion, and also consists of most of Leviticus. P has its main interest in an Aaronid priesthood and in King Hezekiah. P has a low level of literary style, and has an interest in lists and dates.

- D - the Deuteronomist. D consists of most of Deuteronomy. D probably also wrote the Deteronomistic history (Josh, Judg, 1 & 2 Sam, 1 & 2 Kgs). D has a particular interest in the Shiloh priesthood and in King Josiah. D uses a form of Hebrew similar to that of P, but in a different literary style.

The hypothesis postulates that various collections of remembered traditions took written form both in biblical Israel (producing E) and in Judah (producing J) shortly after their separation into two kingdoms (ca 930 BCE). Rival priesthoods allegedly wrote these collections: the priests of Shiloh (in Israel) wrote E; while the Aaronid priests (in Judah) wrote J. Bloom in The Book of J proposed a female author for J, and some who accept this view have argued[citation needed] the case for seeing such an author not as a priest(ess) but as a mere member of the tribe of Judah; many small details in the J source allegedly convey typical female perspectives from the era, not those of males. The king of Israel had removed the priests of Shiloh (Levite like the Aaronids) from power and set up an alternate religion instead. E allegedly reflects these circumstances by describing stories appearing to condemn the changes (such as referring to a Golden Calf — the symbol of the new version of the religion).

The hypothesis then goes on to state that after the fall of Israel to the Assyrians (ca 720 BC), the refugees from Israel brought E to Judah, and in the interests of assimilating those refugees into the general population, an unknown scribe combined the text with J to produce JE. Producing JE, in preference to keeping the texts separate, had the presumed goal of assimilating the refugees rather than having them form a separate subversive nation within Judah. In the circumstances, scholars speculate, the writer of JE may have thought it necessary to retain as much as possible of both J and E, in order to avoid readers and listeners complaining about missing or different texts and thus causing schisms.

The hypothesis suggests that, because of the centralising religious reform instituted by King Hezekiah (reigned ca 715 - 687 BC), the Aaronid priests created a text (P) which rewrote JE in a light favourable to them and to the changes. In addition to performing this change, they removed a few intolerable stories (such as that of the golden calf), and added a few stories. Within the text the author also added a body of laws (constituting most of Leviticus) supported by the Aaronids.

A few generations later, scholars believe, the Shiloh priesthood wrote a law-code more favourable to themselves and conspired with King Josiah (reigned ca 640 - 609 BC) to have it "found" in the Temple so that he could base reforms on it (Hezekiah's descendants had previously undone Hezekiah's reforms). A scribe connected to the Shiloh group subsequently created a text (Dtr1) describing the span of time intervening between Moses and Josiah's rule, embedding the law code at the start in the framework of Moses' dying words.

Dtr1 presented Josiah as a parallel to Moses, an ideal king whose reforms would save Judah. But Josiah died in battle with the Egyptian army (ca 609 BC). Subsequent kings undid his reforms, and shortly afterward Babylon destroyed Judah, burnt the Temple, and killed the royal family (ca 586 BC). The scribe who created Dtr1 made minor additions (Dtr2) to the text to reflect the additional history, and to iron out the flaws in their original presentation of Josiah and the permanence of Judah (by implying that the destruction came as a result of the undoing of Josiah's reforms). The resultant text became known as D.

When Persia conquered Babylon (539 BC), the Persian king Cyrus II sent the exiled élite of Judah back to their homeland, empowering Ezra to dictate the religion. JE and P contained rival histories and rival religious views, and P and D contained rival law-codes. The Jews had to keep both sets of texts in order to avoid alienating each group in the new melding of the nation, and thus to avoid a power struggle or the setting up a nation within a nation. But they also had motivation to iron out the differences: so that people had certainty as to the law-code and to their history. Someone joined the texts together, making only minor additions and changes, creating the Torah, and Ezra read it out. Anyone who disagreed had the Persian king to answer to.

Secondary hypothesis

The secondary hypothesis of the documentary hypothesis suggests that two schools of writers put together the biblical text of the Old Testament: the priests of Shiloh and the Aaronid priesthood.

The priests of Shiloh have associations with the following texts:

- E (the Elohist source of the Torah)

- the Deuteronomistic law code (Deuteronomy 12-26)

- the Deuteronomistic history (most of the material in: Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, I and II Samuel, I and II Kings; compiled from older sources)

The Aaronid priests have associations with the following texts:

- J (the Jahwist source of the Torah)

- P (the Aaronid rewriting of JE)

- the book of generations (used by R in the Torah)

- the book of journeys (used by R in the Torah)

- the Aaronid law code (Lev)

- the Books of Chronicles (compiled from older sources)

- the Book of Ezekiel

History of the hypothesis

Traditional Jewish and Christian beliefs

The traditional Jewish view holds that God revealed his will to Moses at Mount Sinai in a verbal fashion, and that Moses transcribed this dictation verbatim, and that the Pentateuch itself, except for passages dealing with events after the revelation, reflects this transcription exactly[citation needed]. Based on the Talmud (tractate Git. 60a), some believe that God may have revealed the Torah piece-by-piece over the 40 years that the Israelites reportedly wandered in the desert.

The Pentateuch itself does not imply as much. The expression "God said to Moses" shows only the Divine origin of the Mosaic laws, but does not prove that Moses himself codified in the Pentateuch the various laws promulgated by him. It does, on the other hand, ascribe to Moses the literary authorship of at least four sections, partly historical, partly legal, partly poetical. The voice of tradition, however, both Jewish and Christian, proclaimed the Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch so unanimously and constantly that down to the 17th century it did not allow the rise of any serious doubt. (See a Roman Catholic account of the Pentateuch's authenticity.)

Rabbinical biblical criticism

Classical Judaism notes a number of exceptions to the Mosaic authorship account. Over the millennia, scribal errors have crept into the text of the Torah. The Masoretes (7th to 10th centuries CE) compared all extant variations and attempted to create a definitive text. Rabbi Abraham ibn Ezra and Joseph Bonfils observed that some phrases in the Torah present information that people should only have known after the time of Moses. Ibn Ezra hinted, and Bonfils explicitly stated, that Joshua (or perhaps some later prophet) wrote these sections of the Torah. Other rabbis would not accept this view.

The Talmud (tractate Sabb. 115b) states that a peculiar section in the Book of Numbers (10:35 — 36, surrounded by inverted Hebrew letter nuns) in fact forms a separate book. On this verse a midrash on the book of Mishle states that "These two verses stem from an independent book which existed, but was suppressed!" Another (possibly earlier) midrash, Ta'ame Haserot Viyterot, states that this section actually comes from the book of prophecy of Eldad and Medad. The Talmud says that God dictated four books of the Torah, but that Moses wrote Deuteronomy in his own words (Talmud Bavli, Meg. 31b).

Individual rabbis and scholars have on occasion pointed out that the Torah showed signs of non-Mosaic origins in some passages:

- Rabbi Judah ben Ilai held that Joshua must have written the final verses of the Torah (Talmud, B. Bat. 15a and Menah. 30a, and in Midrash Sipre. 357).

- Parts of the Midrash retain evidence of the redactional period during which Ezra redacted and canonized the text of the Torah as it survives today. A rabbinic tradition states that at this time (440 BCE), Ezra edited the text of the Torah, and found ten places in the Torah where lacked certainty as to how to fix the text; these passages appear marked with special punctuation marks called the eser nekudot.

- In the middle ages, Rabbi Abraham ibn Ezra (ca 1092 - 1167 CE) and others noted that several text sequences in the Torah apparently could not have originated in Moses' lifetime. For example, see Ibn Ezra's comments on Gen 12:6; 22:14; Deut 1:2; 3:11; and 34:1, 6. Rabbi Joseph Bonfils elucidated Ibn Ezra's comments in his commentary on Ibn Ezra's work.

- In the 12th century CE the commentator R. Joseph ben Isaac, known as the Bekhor Shor, noted close similarities between a number of wilderness narratives in Exodus and Numbers, in particular, the incidents of water from the rock and the stories about manna and the quail. He hypothesised that both of these incidents actually happened once, but that parallel traditions about these events eventually developed, both of which made their way into the Torah.

- In the 13th century CE Rabbi Hezekiah ben Manoah (known as the Hizkuni) noticed the same textual anomalies that Ibn Ezra had noted; thus R. Hezekiah's commentary on Gen 12:6 notes that this section "is written from the perspective of the future".

- In the 15th century, Rabbi Yosef Bonfils, while discussing the comments of Ibn Ezra, noted: "Thus it would seem that Moses did not write this word here, but Joshua or some other prophet wrote it. Since we believe in the prophetic tradition, what possible difference can it make whether Moses wrote this or some other prophet did, since the words of all of them are true and prophetic?"

- Martin Buber reports how his friend and co-translator of Scripture Franz Rosenzweig jokingly used to expand the sigil R for the redactor to Rabbenu — "Our Master".

For more information on these issues from an Orthodox Jewish perspective, see Modern Scholarship in the Study of Torah: Contributions and Limitations, edited by Shalom Carmy (Jason Aronson, Inc.), and Handbook of Jewish Thought, Volume I, by Aryeh Kaplan (Moznaim Pub.)

The Enlightenment

A number of Enlightenment Christian writers expressed doubts about the traditional Christian view. For example, in the 16th century, Carlstadt noticed that the style of the account of the death of Moses matched the style of the preceding portions of Deuteronomy, suggesting that whoever wrote about the death of Moses also wrote larger portions of the Torah.

By the 17th century some commentators argued outright that Moses did not write most of the Pentateuch. For instance, in 1651 Thomas Hobbes in chapter 33 of Leviathan, argued that the Pentateuch dated from after Mosaic times on account of Deut 34:6 ("no man knoweth of his sepulchre to this day"), Gen 12:6 ("and the Canaanite was then in the land"), and Num 21:14 (referring to a previous book of Moses's deeds). Other skeptics include Isaac de la Peyrère, Spinoza, Richard Simon, and John Hampden. Nevertheless, these people found their works condemned and even banned; the authorities forced de la Peyrère and Hampden to recant, whereas an attempt was made on Spinoza's life.

The French scholar and physician Jean Astruc first introduced the terms Elohist and Jehovist (or Elohistic and Jehovistic) in a little book titled Conjectures sur les memoires originaux, dont il parait que Moses s'est servi pour composer le livre de la Genèse ("Conjectures on the original documents that Moses appears to have used in composing the Book of Genesis"), anonymously printed in 1753. Astruc noted that the first chapter of Genesis uses only the word "Elohim" for God, while other sections use the word "Jehovah". The second and third chapters combine the title and the name, giving rise to a new conception of the Deity as Jehovah Elohim ("Lord-God", as commonly translated in many English Bibles today). He speculated that Moses may have compiled the Genesis account from earlier documents, some perhaps dating back to Abraham, and may have combined these into a single account. So he began to explore the possibility of detecting and separating these documents and assigning them to their original sources. He did this, taking it as axiomatic that one can analyze scriptural documents in the same manner as secular ones, and assuming that the varying use of terms indicated different writers.

Using "Elohim" and "Yahweh" as a criterion, Astruc used columns titled respectively "A" and "B", and also isolated other passages. The A and B narratives he regarded as originally complete and independent narratives. This work gave birth to the practice of Biblical textual criticism that became known as higher criticism.

J. G. Eichhorn brought Astruc's book to Germany and further differentiated the two chief documents through their linguistic peculiarities in 1787. However, neither he nor Astruc denied Mosaic authorship, nor analyzed beyond the book of Exodus.

H. Ewald recognized that the documents that later came to be known as "P" and "J" left traces in other books. F. Tuch showed that "P" and "J" also appeared recognizably in Joshua.

W. M. L. de Wette (1780 — 1849) joined this hypothesis to one asserted by 17th-century commentators by stating that the author(s) of the first four books of the Pentateuch did not write the Book of Deuteronomy. In 1805 he attributed Deuteronomy to the time of Josiah (ca. 621 BC). Soon other writers also began considering the idea. By 1823 Eichhorn abandoned claiming Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch.

19th-Century Theories

About 1822 Friedrich Bleek commented about the original relationship of Joshua to the Pentateuch in its continuation of the narrative in Deuteronomy, of which it formed the conclusion. The letters "J" for Jahwist and "E" Elohist then became associated with the documents.

H. Hupfeld followed K. D. Ilgen in identifying two separate documents that used "Elohim". In 1853 Hupfeld set forth Genesis chapters 1 to 19 and 20 to 50 as providing the two separate Elohistic source documents. He also emphasized the importance of the redactor of these documents. He followed the arrangement of the documents as: First Elohist, Second Elohist, Jehovist, Deuteronomist: J, E, and D.

Karl Heinrich Graf showed that many individual features distinguished Leviticus chapters 17 to 26 from the priestly document. He suggested a fifth document, which August Klostermann named the "Holiness Code" (because this body of laws featured the declaration of God's holiness, Israel's duty to be holy as his people, and extremely frequent use of the word holy).

Julius Wellhausen

In 1886 the German historian Julius Wellhausen published Prolegomena zur Geschichte Israels ("Prolegomena to the History of Israel"). In this book he stated: "according to the historical and prophetical books of the Old Testament the priestly legislation of the middle books of the Pentateuch was unknown in pre-exilic time, and that this legislation must therefore be a late development."(2) The letter "P", for priestly, became associated with this view.

Wellhausen argued that the Bible provides historians with an important source, but that they cannot take it literally. He argued that a number of people wrote the "hexateuch" (including the Torah or Pentateuch, and the book of Joshua) over a long period. Specifically, he narrowed the field to four distinct narratives, which he identified by the aforementioned Jahwist, Elohist, Deuteronomist and Priestly accounts. He also proposed a Redactor, who edited the four accounts into one text. (Some see the redactor as Ezra the scribe.) Using earlier propositions, he argued that each of these sources has its own vocabulary, its own approach and concerns, and that the passages originally belonging to each account can be distinguished by differences in style (especially, the name used for God, the grammar and word usage, the political assumptions implicit in the text, and the interests of the author).

- The "J" source: In this source God's name always appears as YHVH, which scholars transliterated in modern times as Yahveh (German spelling: Jahwe; earlier translators in English used the transliteration Jehovah).

- The "E" source: In this source God's name always comes in the form Elohim (Hebrew for "God", or "Power") until the revelation of God's name to Moses, after which God's name becomes YHVH.

- The "D" or "Dtr" source: The source that wrote the book of Deuteronomy, as well as the books of Joshua, Judges, First and Second Samuel and First and Second Kings.

- The "P" source: The priestly material. Uses Elohim and El Shaddai as names of God.

Wellhausen argued that from the style and point of view of each source one could draw inferences about the times of writing of that source (in other words, the historical value of the Bible lies not in it revealing things about the events it describes, but rather in revealing things about the people who wrote it). He argued that in the progression evident in these four sources, from a relatively informal and decentralized relationship between people and God in the J account, to the relatively formal and centralized practices of the P account, one could see the development of institutionalized Israelite religion.

Subsequent scholars have questioned (and to a large degree rejected) a number of Wellhausen's specific interpretations, including his reconstruction of the order of the accounts as J-E-D-P. Biblical scholars today suggest that he organized the narrative to culminate with P because he believed that the New Testament followed logically in this progression. (This assumption prompted the Jewish scholar Solomon Schechter to refer to Wellhausen's theories as "Higher Antisemitism"). In the 1950s the Israeli historian Yehezkel Kaufmann published The Religion of Israel, from Its Beginnings to the Babylonian Exile, in which he argued for the order of the sources as J, E, P, and D.

Wellhausen resigned his post as professor of biblical studies, stating that his hypotheses had started to make his students (trainees for the Evangelical priesthood) unsuitable as ministers.

The modern era

Other scholars immediately seized upon the documentary understanding of the origin of the five books of Moses, and within a few years it became the predominant hypothesis. While subsequent scholarship has dismissed many of Wellhausen's specific claims, most historians still accept the general idea that the five books of Moses had a composite origin.

Note that the term "documentary hypothesis" does not refer to one specific hypothesis. Rather, this name applies to any understanding of the origin of the Torah that recognizes (basically) four sources somehow redacted together into a final version. One could claim that one redactor wove together four specific texts, or one could hold that the entire nation of Israel slowly created a consensus work based on various strands of the Israelite tradition, or anything in between. Gerald A. Larue writes, "Back of each of the four sources lie traditions that may have been both oral and written. Some may have been preserved in the songs, ballads, and folktales of different tribal groups, some in written form in sanctuaries. The so-called 'documents' should not be considered as mutually exclusive writings, completely independent of one another, but rather as a continual stream of literature representing a pattern of progressive interpretation of traditions and history" (Old Testament Life and Literature 1968).

Richard Elliot Friedman

In recent years researchers have made attempts to separate the J, E, D, and P portions. Richard Elliott Friedman's Who Wrote The Bible? offers a very reader-friendly and yet comprehensive argument explaining Friedman's opinions as to the possible identity of each of those authors and, more important, why they wrote what they wrote. Harold Bloom then wrote The Book of J, in which his co-author, Hebrew translator David Rosenberg, claims to have reconstructed the book that J wrote (though, certainly, some of J's original contribution could have become lost in the consolidation, if one accepts the four-author hypothesis). Bloom (picking up on Friedman's earlier speculation) also indicates a belief indentifying J as a woman, but other scholars do not accept this.

More recently, Friedman published The Hidden Book in the Bible, in which he makes a comprehensive argument for his hypothesis that J wrote not only the portions of the Torah commonly attributed to J, but also sections of Judges, Joshua and First and Second Samuel (which Bloom and earlier Biblical scholars attributed to another source, the Court History of David), which contained the bulk of the accounts of the life of King David, with a close thematic interrelationship between the earlier and later portions of what Friedman presents as a single united work by one author of Shakespearean literary ability.

Friedman has also published The Bible with Sources Revealed (2003), his own translation of the Torah with the material from each source (as he sees them) in a different color of ink or a different typeface.

The hypothesis of female authorship

Some modern scholars argue for the possibility of female authorship based on the fact that a upper-class woman (in Judah especially) may have had greater status and access to education than a lower-class man at the that time (Richard Freidman, Who wrote the Bible?), making female authorship at least possible. Scholars have particularly singled out the J source as a candidate for female authorship (see above for discussion of the J source). However, Richard Friedman in Who wrote the Bible notes that while these facts leave the door open to female authorship, they do not constitute a proof of it either way.

Debates on the hypothesis

Opposing views

Most Orthodox Jews and many conservative Christians reject the documentary hypothesis entirely and accept the traditional view that Moses essentially produced the whole Torah. Jewish sources predating the emergence of the documentary hypothesis offer alternative explanations for the stylistic differences and alternative Divine names from which the hypothesis originated. For instance, some regard the Tetragrammaton as an expression of mercifulness (middath ha-rachamim) while Elohim refers to strict judgement (middath ha-din); traditional Jewish literature cites this concept (first found in Mechilta section Beshalach) copiously.

Most Orthodox Jews and many conservative Christians accept the divine origin of the Pentateuch in its entirety as a given. They usually reject the documentary hypothesis as incompatible with their religious view of the Bible. Some religious conservatives believe that Moses was the author of much of the text and was the editor and compiler of the rest of the text. Others who reject the hypothesis allow for considerable post-Mosaic editing of the Pentateuch, though not along J.E.D.P. lines. Many conservative scholars argue for the literary unity of the books[1].

Over the last century, an entire literature has developed within conservative scholarship and religious communities dedicated to the refutation of higher biblical criticism in general and of the documentary hypothesis in particular.

R. N. Whybray's The Making of the Pentateuch offers a critique of the hypothesis from a critical perspective. Biblical archaeologist W.F. Albright stated that even the most ardent proponents of the documentary hypothesis must admit that, like the Book of Jasher, and the Book of the Wars of the Lord, no tangible, external evidence for the existence of the hypothesized J, E, D, P sources exists. The late Dr. Yohanan Aharoni, in his work Canaanite Israel during the Period of Israeli Occupation (referenced from simpletoremember.com states that "[r]ecent archaeological discoveries have decisively changed the entire approach of Bible critics" and that later authors or editors could not have put together or invented these stories hundreds of years after they happened.

Some studies claim to show a literary consistency throughout the Pentateuch. For instance, a 1980 computer-based study at Hebrew University in Israel (as summarised at simpletoremember.com) concluded that a single author most likely wrote the Pentateuch. Some Bible scholars have rejected this study for a number of reasons, including the fact that a single later editor can rewrite a text in a uniform voice (see simpletoremember.com). On the other hand, say critics like James Orr, if one admits that the texts speak with a uniform voice, much of the initial plausibility of the hypothesis evaporates. Some, perhaps most notably Gleason Archer, have proposed harmonisations of the Torah which allegedly resolve the discrepancies.

Other criticisms arise from several directions.

- Axel Olrik's Principles for Oral Narrative Research states that preserving various versions of the same material without regularizing it signals accuracy in transmitting an oral tradition, not a failure of editorship. (§15)

- Umberto Cassuto in the 2006 version of his work listed below, points out an instance of "emendation" which, in modern scientific terms, equates to falsifying the data so that it supports an assertion.

- In the same work Cassuto discusses the deconstruction of a parallel formation which disrupts a grammatical structure, a violation of Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis.[citation needed]

Various views of supporters

Bible-scholars supporting the documentary hypothesis continue to debate the specifics — as commonly happens in the fields of archaeology, history and science.

While accepting the documentary hypothesis as correct in outline, some scholars believe that the Wellhausen School overemphasized the use of written sources to the neglect of the oral traditions that underlay the sources. The oral traditionalists, starting with Hermann Gunkel (the "father of form criticism"), viewed the narratives of the Torah as originally stories handed down orally in the form of sagas, much like the Iliad or Odyssey, passed down via word of mouth by an illiterate people. Eventually scribes wrote these oral traditions down.

Form and tradition history do not necessarily contradict the documentary hypothesis; one could use these methods to try to reconstruct the oral history behind Wellhausen's written sources. On the other hand, one can take oral tradition as an alternative to written sources. The Scandinavian scholar Ivan Engnell has espoused this point of view: he believes that the Hebrew people transmitted the whole of the Torah orally into the post-exilic period, at which point an author — whose attributes match those ascribed to the Redactor R of the documentary hypothesis — wrote it down in a single document.

The Heidelberg professor Rolf Rendtorff expresses the view that larger chunks of narrative within the texts which the documentary hypothesis calls J and E evolved independently of other parts of each of these texts, and did not form part of a large text like J or E. This view proposes that a Deuteronomic redactor combined the narratives editorially only at a later stage. In this synthesis, Rendtorff allows for a post-exilic P source, but one far reduced from the notions of Wellhausen.

Some critical analysis rejects the partitioning scheme of Wellhausen. For example Hans Heinrich Schmid, in his 1976 work, Der sogenannte Jahwist ["The So-called Yahwist"], almost completely eliminates the J document. According to Blenkinsopp (1992), this approach — if taken to the logical extreme — eliminates all narrative sources other than the Deuteronomic author.

Other modifications to the documentary hypothesis appeared in the mid-1970s in the work of John Van Seters, and continued into the 1980s and 1990s. Dating the J material to the period of the exile (6th century BCE), but maintaining its focus as identity-creation, Van Seters' work continues to use the terminology established in the 18th and 19th centuries, but holds a different view regarding the compositional process. While Schmid and other European scholars continue to think in terms of documents and redactors, Van Seters proposes a process of supplementation in which subsequent groups modify earlier compositions to include their points-of-view and to change the focus of the narratives.

The modifications to the documentary hypothesis suggested by Van Seters and others have provided challenges for biblical scholars, particularly in the United States of America. Many see the supplementary model as incompatible with the established views of the documentary models of composition. They correctly see a challenge to the early dating for composition and the problematic control of documentary materials, for which the literary evidence appears harder and harder to maintain.

References

John Rogerson provides an authoritative and readable overview in Old Testament Criticism in the Nineteenth Century: England and Germany (1985).

- Allis, Oswald T. The Five Books of Moses, Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Co., Phillipsburg, New Jersey, USA, 1949, pages 17 and 22.

- Archer, Gleason. A Survey of Old Testament Introduction. Chicago: Moody, 1994.

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph The Pentateuch, Doubleday, NY, USA 1992.

- Bloom, Harold and Rosenberg, David The Book of J, Random House, NY, USA 1990. ISBN 0-8021-4191-9.

- Campbell, Joseph "Gods and Heroes of the Levant:1500-500 B.C." The Masks of God 3: Occidental Mythology, Penguin Books, NY, USA, 1964.

- Cassuto, Umberto. The Documentary Hypothesis and the Composition of the Pentateuch, Magnes, 1961. ISBN 965-223-479-6.

- Cassuto, Umberto. The Documentary Hypothesis (Contemporary Jewish Thought), Shalem, 2006. ISBN 965-7052-35-1.

- Clines, David J. A. The Theme of the Pentateuch. JSOTSup. 10. Sheffield: JSOT Press, 1978.

- Dever, William G. What Did The Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It? William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., Grand Rapids, MI, USA, 2001. ISBN 0-8028-4794-3

- Finkelstein, Israel and Silberman, Neil A. The Bible Unearthed, Simon and Schuster, NY, USA, 2001. ISBN 0-684-86912-8

- Fox, Robin Lane, The Unauthorized Version. A classics scholar offers a measured view for the layman.

- Friedman, Richard E. Who Wrote The Bible?, Harper and Row, NY, USA, 1987. ISBN 0-06-063035-3. This work does not constitute a standard reference for the Documentary Hypothesis, as Friedman in part describes his own theory of the origin of one of the sources. Rather, it offers an excellent introduction for the layman.

- Friedman, Richard E. The Hidden Book in the Bible, HarperSan Francisco, NY, USA, 1998.

- Friedman, Richard E. The Bible with Sources Revealed, HarperSanFrancisco, 2003. ISBN 0-06-053069-3.

- Garrett, Duane A. Rethinking Genesis: The Sources and Authorship of the First Book of the Bible, Mentor, 2003. ISBN 1-85792-576-9.

- Kaufmann, Yehezkel, Greenberg, Moishe (translator) The Religion of Israel, from Its Beginnings to the Babylonian Exile, University of Chicago Press, 1960.

- Larue, Gerald A. Old Testament Life and Literature, Allyn & Bacon, Inc, Boston, MA, USA 1968

- McDowell, Josh More Evidence That Demands a Verdict: Historical Evidences for the Christian Scriptures, Here's Life Publishers, Inc. 1981, p. 45.

- McDowell, Josh The New Evidence That Demands a Verdict, Thomas Nelson Inc.,Publishers. 1999, pages: 411, 528.

- Mendenhall, George E. The Tenth Generation: The Origins of the Biblical Tradition, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973.

- Mendenhall, George E. Ancient Israel's Faith and History: An Introduction to the Bible in Context, Westminster John Knox Press, 2001. ISBN 0664223133

- Nicholson, E. The Pentateuch in the Twentieth Century: The Legacy of Julius Wellhausen, Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Rogerson, J. Old Testament Criticism in the Nineteenth Century: England and Germany, SPCK/Fortress, 1985.

- Spinoza, Benedict de A Theologico-Political Treatise Dover, New York, USA, 1951, Chapter 8.

- Tigay, Jeffrey H. "An Empirical Basis for the Documentary Hypothesis" Journal of Biblical Literature Vol.94, No.3 Sept. 1975, pages 329-342.

- Tigay, Jeffrey, Ed. Empirical Models for Biblical Criticism University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, PA, USA 1986

- Van Seters, John. Abraham in History and Tradition Yale University Press, 1975.

- Van Seters, John. In Search of History: Historiography in the Ancient World and the Origins of Biblical History Yale University Press, 1983.

- Van Seters, John. Prologue to History: The Yahwist as Historian in Genesis Westminster/John Knox, 1992.

- Van Seters, John. The Life of Moses: The Yahwist as Historian in Exodus-Numbers Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster/John Knox, 1994. ISBN 066422363X

- Wiseman, P. J. Ancient Records and the Structure of Genesis Thomas Nelson, Inc., Nashville, TN, USA 1985. ISBN 0-8407-7502-4

- Whybray, R. N. The Making of the Pentateuch: A Methodological Study JSOTSup 53. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1987.

Notes

See also

External links

- Redaction Theory (Documents Hypothesis)

- Biblical criticism and the origin of the Torah Frequently Asked Questions. Retrieved from "Judaism FAQs" site on 2006-10-17

- A Summary of the Documentary Hypothesis

- Teaching Bible using the Documentary Hypothesis

- Detailed timeline and chart of sources of the Hebrew Bible

- Reading the Old Testament

- Documentary Hypothesis (pdf)

Criticisms

- "On Bible Criticism and Its Counterarguments: A Short History" - on the SimpleToRemeber.com Judaism Online website

- Smith, Colin: "A Critical Assessment of the Graf-Wellhausen Documentary Hypothesis", June 2002. Retrieved from the Alpha and Omega Ministries website on 26 July 2006.

- "The Documentary Source Hypothesis"

- Who Wrote The First 5 Books of the Bible? - articles on the GospelPedlar website from 1895 to 1964

- Doug Beaumont, "Did Moses Write the Pentateuch?" (The souldevice.org website apparently no longer serves this article as of 6 November 2006.)

- "Mosaic Authorship of the Pentateuch — Tried and True" - article by Eric Lyons and Zach Smith from ApologeticsPress (2003). Retrieved on 2006-08-08.

- Don Closson, "Did Moses Write the Pentateuch?" - from Probe Ministries

- John Ankerberg and John Weldon, "Biblical Archaeology - Silencing the Critics"

- Russell Grigg, "Did Moses really write Genesis?" - on the "Answers in Genesis" Christian apologetic ministry website

- Dei Verbum - "On Divine Revelation", available on the Vatican's website

Alternative hypotheses

- Curt Sewell, "The Tablet Theory of Genesis Authorship"

- The Wiseman Hypothesis

- Gordon Wenham, "Pentateuchal Studies Today" - from Themelios 22.1 (October 1996): 3-13.