Kaidu–Kublai war

| Kaidu–Kublai war | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Division of the Mongol Empire | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Kaidu Baraq Duwa Mengu-Timur |

Kublai Khan Temür Khan Abagha | ||||||

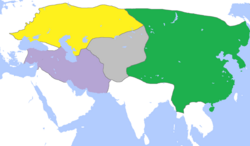

The Kaidu–Kublai war was a war between Kaidu, the leader of the House of Ögedei and the de facto khan of the Chagatai Khanate in Central Asia, and Kublai Khan, the founder of the Yuan dynasty in China and his successor Temür Khan that lasted a few decades from 1268 to 1301. It followed the Toluid Civil War (1260–1264) and resulted in the permanent division of the Mongol Empire. By the time of Kublai's death in 1294, the Mongol Empire had fractured into four separate khanates or empires: the Golden Horde khanate in the northwest, the Chagatai Khanate in the middle, the Ilkhanate in the southwest, and the Yuan dynasty in the east based in modern-day Beijing.[1] Although Temür Khan later made peace with the three western khanates in 1304 after Kaidu's death, the four khanates continued their own separate development and fell at different times.

History

After the Toluid Civil War, Kublai Khan summoned Kaidu at his court, but Kaidu avoided appearing at his court, and his enmity was a constant obstacle to Kublai's ambitions to control the whole Mongol Empire.

Baraq was dispatched to Central Asia to take the throne of Chagatai Khanate in 1266, and almost immediately, he repudiated the authority of Kublai as Great Khan. Kaidu and Baraq fought for a while, and Kaidu gained control of the region around Bukhara. Kaidu convinced Baraq to attack the Persia-based Ilkhanate, which was an ally of Kublai Khan's Yuan dynasty based in China. A peace treaty was made among Mengu-Timur, khan of the Golden Horde, Kaidu and Baraq against the Yuan dynasty and the Ilkhanate in around 1267. However, Baraq suffered a large defeat at Herat on July 22, 1270 against Ilkan Abagha. Baraq died en route to meet Kaidu who had been waiting for his weakness. The Chagatayid princes including Mubarak Shah submitted to Kaidu and proclaimed him as their overlord. Sons of Baraq rebelled against Kaidu but they were defeated. Many of the Chagatayid princes fled to the Ilkhanate. Kaidu's early attempt to rule the Chagatayids faced a serious resistance. The Mongol princes such as Negübei, whom he appointed khan of the House of Chagatai revolted several times. Stable control came when Duwa was made khan who became his number two in 1282. The Golden Horde based in Russia also became an ally of Kaidu.

In 1275 Kaidu invaded Ürümqi and demanded its submission, but the Buddhist Idiqut (then a vassal of Yuan) resisted. Kublai sent a relief force to expel him. Kublai's son Nomukhan and generals occupied Almaliq in 1266–1276, to prevent Kaidu's invasion. In 1277, a group of Genghisid princes under Möngke's son Shiregi rebelled, kidnapping Kublai's two sons and his general Antong. The rebels handed Antong to Kaidu and the princes to Mengu-Timur. The army sent by Kublai Khan drove Shiregi's forces west of the Altai Mountains and strengthened the Yuan garrisons in Mongolia and Xinjiang. However, Kaidu took control over Almaliq.[2] Nevertheless, rulers of the Golden Horde withdrew their support from Kaidu after the death of Mengu-Timur; three leaders, Noqai, Todemongke and Konichi, of the Golden Horde made peace with Kublai in 1284.[3] Both Noqai and Todemongke made peace with the Ilkhan Ahmad Teguder as well.[4] To attract military support from the Jochids, Kaidu sponsored his own candidate Kobek for the throne of the Left wing of the Golden Horde from early 1290s. Golden Horde's troops clashed with Kobek, supported by Kaidu's army, several times.

In 1293 Tutugh, a Kipchak commander of Kublai Khan occupied the Baarin tumen, who were allies of Kaidu, on the Ob River. Kublai Khan died in the next year and was succeeded by Temür Khan (Emperor Chengzong). From 1298 on Duwa increased his raids on the Yuan. He launched a surprise attack against the Yuan garrison under Temür's uncle Kokechu in Mongolia and captured Temür's son-in-law, Korguz of the Ongud when he and his commanders were drunk.[5] However, Duwa was defeated by the Yuan army under Ananda in Gansu and his son-in law and several relations were captured. Although, Duwa and the Yuan generals agreed to exchange their prisoners, Duwa and Kaidu executed Korguz in revenge and cheated the Yuan officials. To reorganize the Yuan defence system in Mongolia, Temür appointed Darmabala's son Khayishan to replace Kokechu. The Yuan army defeated Kaidu south of the Altai Mountains. However, in 1300, Kaidu defeated Khayishan's force. Then Kaidu and Duwa mobilized a large army to attack Karakorum the next year. The Yuan army suffered heavy losses while both sides could not make any decisive victory in September. Duwa was wounded in the battle and Kaidu died soon thereafter.

Until this time Kaidu had waged almost continuous warfare for more than 30 years against Kublai and his successor Temür, though he eventually died in 1301 after the battle near Karakorum. The Kaidu–Kublai war had effectively deepened the fragmentation of the Mongol Empire, although a peace later came in 1304 which established the nominal suzerainty of the Yuan Emperors (or Khagans) over the western khanates.

See also

References

- ^ The Cambridge History of China: Alien Regimes and Border States. p. 413.

- ^ Atwood, Christopher Pratt (2004). "Qubilai Khan". Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. Facts on File. p. 459.

- ^ Thomas T. Allsen, 1985. The Princes of the Left Hand: an introduction to the history of the Ulus of Orda in the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries. Archivum Eurasiae Medii Aevi, 5, 5–40.

- ^ Judith Pfeifer – “Aḥmad Tegüder’s Second Letter to Qalā’ūn (682/1283).’ In History and Historiography of Post-Mongol Central Asia and the Middle East, edited by Judith Pfeiffer & Sholeh A. Quinn, 167–202. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2006.

- ^ The Cambridge History of China: "Alien regimes and border states, 907–1368", p. 502.