Italian Grand Prix

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2015) |

| Autodromo Nazionale di Monza (2000–present) | |

| |

| Race information | |

|---|---|

| Number of times held | 89 |

| First held | 1921 |

| Most wins (drivers) | |

| Most wins (constructors) | |

| Circuit length | 5.793 km (3.600 miles) |

| Race length | 306.720 km (190.596 miles) |

| Laps | 53 |

| Last race (2019) | |

| Pole position | |

| |

| Podium | |

| |

| Fastest lap | |

| |

The Italian Grand Prix (Italian: Gran Premio d'Italia) is the fifth oldest national Grand Prix (after the French Grand Prix, the American Grand Prize, the Spanish Grand Prix and the Russian Grand Prix), having been held since 1921. In 2013 it became the most held (the 2019 edition was the 89th). It is one of the two Grand Prix (along with the British) which has run as an event of the Formula One World Championship Grands Prix every season, continuously since the championship was introduced in 1950. Every Formula One Italian Grand Prix in the World Championship era has been held at Monza except in 1980, when it was held at Imola.

The Italian Grand Prix counted toward the World Manufacturers' Championship from 1925 to 1928 and toward the European Championship from 1931 to 1932 and from 1935 to 1938. It was designated the European Grand Prix seven times between 1923 and 1967, when this title was an honorary designation given each year to one Grand Prix race in Europe. Four editions before the World Championship were held in places other than Monza: Montichiari (1921), Livorno (1937), Milan (1947) and Turin (1948).

History

Origins

The first Italian Grand Prix motor racing championship took place on 4 September 1921 at a 10.7-mile (17.3 km) circuit near Montichiari, which had been the site of the Gordon Bennett races in the early 1900s.[1] However, the race is more closely associated with the course at Monza, a racing facility just outside the northern city of Milan, which was built in 1922 in time for that year's race, and has been the location for most of the races over the years.

Autodromo Nazionale di Monza

The Autodromo Nazionale di Monza was completed in 1922 and was just the third permanent autodrome in the world at that time; Brooklands in England and Indianapolis in the United States were the two others. European motor racing pioneers Vincenzo Lancia and Felice Nazzaro laid the last two bricks at Monza. The circuit was 10 km (6.25 miles) long, with a flat banked section and a road circuit combined into one. It was fast, and always provided excitement. The 1923 race included one of Harry A. Miller's rare European appearances with his single seat "American Miller 122" driven by Count Louis Zborowski of Chitty Chitty Bang Bang fame.

The 1928 race was the first of many tragedies that befell this venue. Italians Emilio Materassi in a Talbot and Giulio Foresti in a Bugatti were battling around the fast circuit. As they came off the banking onto the left side of the pit straight, one of the front wheels of Materassi's overtaking Talbot touched one of the rear wheels of the Bugatti. Materassi lost control of the car, swerved left, cleared a 15-foot wide and 10-foot deep ditch and ploughed into the unprotected grandstand opposite the pits, killing himself and 27 spectators, and injuring another 26. It was the worst accident in motor racing history and remained so until the 1955 24 Hours of Le Mans. The Italian Grand Prix went on a three-year hiatus (but the alternative non-championship Monza Grand Prix was run in 1929 and 1930) until the 1931 race, held in late May instead of the traditional early September, was won by Giuseppe Campari and Tazio Nuvolari, sharing an Alfa Romeo. The 1931 race was something of an endurance race; it took ten hours to complete. The great Nuvolari won again in a shortened 1932 race, this time held in early June.

In 1933, with the race being held this time at the traditional timeframe of early September, disaster struck again. Three top drivers were killed during three heat races. There was a reported patch of oil on the south banking that had come from a Duesenberg, driven by Count Carlo Felice Trossi, and Giuseppe Campari in a Ferrari-entered Alfa Romeo and his protege Baconin Borzacchini in a Maserati were already battling ferociously; and Borzacchini and Campari went through the south banking on the first lap, wheel to wheel. Borzacchini went through the oily patch, lost control, spun wildly and the Maserati then overturned and violently flipped multiple times, and by the time the wrecked car came to a stop, Borzacchini was pinned underneath and was being crushed by his car, not having been thrown out. And while Borzacchini's Maserati had been crashing all over the track, Campari swerved to avoid him, and by doing this, his car went up and flew off the banking and crashed into trees situated right next to the track. Campari broke his neck and was killed instantly, and Borzacchini died later that day in a Monza hospital.

Prior to the third heat, there was a drivers meeting to discuss the oil patch, and it was decided to clean it up. on the eighth lap, Polish aristocrat Count Stanislas Czaykowski was on the south banking when his Bugatti's engine blew up, and a fuel line then broke. The fuel from the Bugatti's tank caught fire after touching the very hot front section of the Bugatti where the engine and gearbox were and the burning fuel sprayed onto Czaykowski. Blinded by the smoke and flames on him, he went up and flew off the banking- at the same spot where Campari and Borzacchini had crashed. The Polish driver, unable to put out the flames on his body which was fuelled by the fuel from his wrecked Bugatti, then burned to death. Italian Luigi Fagioli was declared the winner of the event.

Enzo Ferrari, who had been close to Campari and Borzacchini; the former deciding to defect from Ferrari's team to Maserati, became hardened by this tragedy. Today, racing historians conclude that the events of this race marked a watershed, notably for Enzo Ferrari. It was the end to the joyful era of racing and the beginning of a harsher new age. Safety in those days was completely non-existent. The circuit's condition was virtually identical of that to an ordinary town and country road, except instead of the surface being made of dirt and/or tarmac, it was made of tarmac, concrete and/or bricks. Spectators often stood very close to or even next to the track and they had no protection of any kind other than common sense. What was particularly tragic about Campari's death was that he had announced his retirement at the French Grand Prix two months earlier, to focus on his opera singing exploits.[2]

The Florio circuit and other locations

After the disastrous 1933 race, something had to be done to Monza. In 1934 a short version of Florio Circuit (introduced in 1930 for Monza Grand Prix) was used: the drivers had to start from the main straight but taking the south curve of the high speed ring (interrupted by a double chicane) in the opposite direction compared to the usual one; then, through the connection introduced a few years before by Florio, they took the central straight, the south curve (also interrupted by a chicane) and the main straight; finally a 180 ° hairpin turned back to the finish line. This configuration was considered too slow and since the following year Florio circuit (with five chicanes) was used. These races were at a time when Mercedes and Auto Union became involved in motor racing; the German Silver Arrows won all of these races; with superstar Rudolf Caracciola winning in 1934 and in 1937 when the Italian Grand Prix was held at a street circuit in Livorno. 1938 saw a return to Monza, which was won by Nuvolari driving a mid-engined Auto Union; just after the race renovation works began but in 1939 World War II broke out and the Italian Grand Prix did not return until 1947.

1947 saw the Italian Grand Prix being held at a fairgrounds park in the city of Milan's district of Portello , and this race was won by Italian Carlo Felice Trossi driving an Alfa Romeo. Italian Giovanni Bracco went off the road in his Delage and crashed into a group of spectators, killing five. This venue was never used again for racing, and 1948 saw it being held in Valentino Park, a public park in Turin. The 1949 race returned to Monza where it stayed for the next 30 years with the configuration ready before the war but never used yet.

Monza's redevelopments (1949–1979)

Monza's banking had been built over and only the road circuit was used, which had been modified slightly. The new long, fluid final corner was now two around 90-degree corners. 1949 saw Italian new-boy Alberto Ascari, son of the late 1924 Italian Grand Prix winner Antonio Ascari, win in his Ferrari; Enzo Ferrari was now building his own cars instead of running Alfa Romeos. 1950 saw the new Formula One Championship being established. The race and the first championship was won by Giuseppe "Nino" Farina, driving a supercharged Alfa Romeo 158. 1951 saw Ascari win again, after the competitive Alfas of Farina and Argentine Juan Manuel Fangio ran into engine problems. 1952 saw Ascari complete his domination of that season. 1953 Fangio won in a Maserati; although Ascari had already won the championship at the Swiss Grand Prix. 1954 turned out to be an interesting race; as up-and-comer Stirling Moss in a Maserati passed both Fangio's Mercedes and Ascari's Ferrari. The furious pace saw the retirement of Moss and Ascari and Fangio went on to win while Moss pushed his Maserati 250F over the line.

After the 1954 running, work began on entirely revamping the circuit. New facilities were built and a new corner, the Parabolica, was built right before the pits. Extra track used for a short course was eliminated. The biggest change was the construction of the new Monza banking. Built on top of where the almost flat, narrow original banking was, these huge concrete bankings, called the sopraelevata curves, were built in the same shape as the original banking had been. The only significant difference was that the Curva Sud was moved slightly to the north. This course was combined with the road course for the 1955 event, which was won by Fangio and was the last race contested by a full-fledged Mercedes factory effort in Formula One until 2010. The 10 km Monza circuit was now so fast that F1 cars were averaging 135+ mph per lap- though rather unremarkable by today's standards, these average speeds were even faster than the Indianapolis Speedway oval in the United States. 1956 saw an exciting race, with championship contenders Fangio, Briton Peter Collins (both in Ferraris) and Frenchman Jean Behra in a Maserati fight over the win. Stirling Moss was already out of championship contention; and Fangio retired with a broken steering arm. The Ferrari team called for Italian Luigi Musso to hand his car over to Fangio. Musso ignored the order so Collins came in and handed his car and his championship chances to Fangio. Behra had retired early with a magneto problem in his own car and took over his teammate Umberto Maglioli's car; but he retired that car, too. Musso ended up leading after Moss ran out of fuel coming through Vialone. Moss was able to refuel his car and storm off after Musso and eventually the Italian retired with steering problems, and Moss, with Fangio catching him up fast, stormed round the track to take victory. Fangio took second and his fourth Drivers' Championship.

1957 saw the organizers choose to use the road circuit only, as the rough, poorly constructed banking had caused problems for the Ferrari and Maserati cars the year before. Moss won again in a Vanwall, and Briton Tony Brooks won next year's race, and Moss won the 1959 event in a Cooper-Climax. 1960, however was not so straightforward. Ferrari with their front-engined cars, had lost out to the advanced mid-engined British cars. Seeing an opportunity, the Italian organizers decided to re-include the banking with the road circuit, making Monza even faster and more in favour to the powerful Ferraris. The British teams were unhappy as they cited the fragility of the banking, which was extremely rough, of very poor quality and was supported by stilts rather than solid bedrock; and that it was too dangerous for Formula One cars. The British teams boycotted the race, so Ferrari had no competition. American Phil Hill took victory, in what was the last victory for a front-engined Formula One car.

1961 saw a return to the combined circuit, but it was to see yet another tragedy. Two Ferrari drivers, Hill and German count Wolfgang von Trips, came into the race with a chance at winning the championship. Fighting for fourth place while Hill was leading and while von Trips approached the Parabolica, the Briton Jim Clark slightly moved over into the path of the German and the two collided. Von Trips crashed into an embankment next to the road and then went flying into a crowd of people standing on it. Von Trips was thrown out of his car and was killed, as were 14 spectators. Clark survived but was hounded by Italian police for months after the incident. Hill won the race and the championship by one point. The race was not stopped, allegedly to assist rescue work for the injured.

1962 saw a return to the road circuit only and the banking was never used again for Formula One. It still stands, but in decrepit condition for a long time before being restored in the early 2010s; the last time it was used was in 1969 for the 1000 kilometre sports car race that year. Briton Graham Hill won the race, and won the Drivers' Championship in South Africa soon afterward. 1963 saw an attempted use of the extremely fast full circuit again, and the drivers ran the course during Friday practice but the concrete banking was so rough and bumpy that cars were being mechanically torn apart. It was feared that there would be no finishers for the race itself. Briton Bob Anderson's Lola crashed after losing a wheel on the banking, although he was not injured); the drivers then threatened to walk off unless they raced on the road circuit only, which is what happened. Jim Clark won the race in a Lotus. Ferrari driver John Surtees won in 1964, and Briton Jackie Stewart won his first of 27 Grand Prix victories in 1965, driving for BRM. Against team orders, he fought hard with his teammate Graham Hill, Hill made a mistake at the Parabolica and Stewart was in command; this was all to the chagrin of team boss Tony Rudd. 1966 saw Italian Ludovico Scarfiotti win, and no other Italian has won the race since. 1967 was to be a race of interest and was to produce the first of three close finishes on the fast Monza circuit over the next four years. Surtees, now driving for Honda, battled with Australian Jack Brabham, and Surtees won the race by two-tenths of a second; and Clark, who had problems at the beginning of the race and lost a whole lap, stormed around the circuit, equalled his pole position time and unlapped himself to take the lead- but his fuel pump broke and he coasted over the line to finish third. 1969 saw four drivers; Stewart, Austrian Jochen Rindt, Frenchman Jean-Pierre Beltoise and New Zealander Bruce McLaren battle right down to the line. Stewart came out on top and beat Rindt by eight-hundredths of a second. The four drivers were all within two-tenths of a second of each other. With this win, Stewart won his first of three championships.1970 saw Rindt's fatal crash during qualifying at the wheel of his rear wing-less Lotus; his car suffered brake shaft failure, veered off the track, hit and went under the improperly-secured guardrail on the left and spun multiple times. Rindt died not because of the impact but because he had not properly secured his seat belts and the buckle had slit his throat. Rindt became the only posthumous world champion, after Ferrari driver Jacky Ickx failed to overhaul Rindt. Ickx's teammate Clay Regazzoni won the race, which saw 28 lead changes. 1971 was to see the third close finish in four years. Briton Peter Gethin, Swede Ronnie Peterson, Frenchman François Cevert, Briton Mike Hailwood and New Zealander Howden Ganley battled for the lead all race. On the last lap, Peterson got the inside line for the Parabolica, but Gethin got in front going alongside Peterson through the long right-hand corner, and beat Peterson to the checkered flag by the slimmest of margins; one-one hundredth of a second. Cevert and Hailwood finished within two-tenths and Ganley was half a second behind.

1972 saw changes to Monza. The 1971 race was the fastest Formula One race ever at that point in time. It was really just a bunch of straights and fast corners and F1 cars had become increasingly advanced and much faster, and the drivers were constantly slipstreaming each other around the circuit. A small chicane was put at the end of the pit straight and another one at the Vialone curve; Brazilian Emerson Fittipaldi won that race and his first Drivers' Championship at only 25 years of age. His chief rival Jackie Stewart went out at the start with a broken gearbox. In 1973, Stewart punctured a tire early in the race and went into the pits to have it changed; he came out in 20th place and finished fourth in the race while Fittipaldi finished second; this was enough for Stewart to win his third and final Drivers' Championship. 1974 saw further changes with the Vialone chicane changed and renamed Variante Ascari, which was the place where Alberto Ascari was killed in 1955 testing a Ferrari sportscar. Like the year before, Peterson won and Fittipaldi finished second, now driving for McLaren. 1975, however, was an event to remember. Ferrari, which had regrouped completely under the leadership of Luca di Montezemolo, reached the high point of its resurgence.

The Ferrari camp was feeling relaxed while rising star and championship leader Niki Lauda was leading the Drivers' Championship, and the team was leading the Constructors' Championship. Fittipaldi and Argentine Carlos Reutemann had to win in order to have a chance at staying in the championship chase. When the race started, Lauda's teammate Clay Regazzoni took the lead, with Lauda following; and Fittipaldi stormed round the circuit in an effort to catch the two Ferraris. Fittipaldi passed Lauda for second but this did not matter as Lauda only needed fifth to secure the drivers' title. Regazzoni took victory, followed by Fittipaldi and Lauda, who won his first drivers' title and Ferrari also won the Constructors' Championship at the same event.1976 saw further changes to Monza's layout. Two chicanes, called Variante Rettifilo were installed just before the Curva Grande, and another chicane, the Variante della Roggia, was installed just before the Lesmo bends. Lauda, who had come back to racing only six weeks after his horrendous crash at the Nürburgring; finished fourth while Peterson won. 1977 saw Italian-American Mario Andretti win in a Lotus; but the next year's race was to add another page of tragedy to Monza's history.

Peterson had re-joined Lotus at the beginning of the 1978 season and had challenged his teammate Andretti all the way. Peterson had crashed his car in practice, and had to use Andretti's spare car, not a comfortable fit for the tall Swede, in contrast to the diminutive American. As the race started, there was a huge, fiery multi-car pile-up on the approach to the first corner. One of the victims was Peterson; his car slammed head-on into the Armco barriers and had caught fire. Instead of the ill-equipped marshals, Briton James Hunt, with the help of Frenchman Patrick Depailler and Regazzoni ran towards Peterson's aid and pulled him out of the burning Lotus. Peterson suffered severe leg injuries, and he died from embolism complications a day later. With Peterson's retirement from the race, Andretti won the Drivers' Championship. The race itself was an interesting one; during the parade lap South African Jody Scheckter lost a wheel from his Wolf at the second Lesmo curve and hit an Armco barrier right next to the track. Andretti, Hunt, Lauda, Fittipaldi and Reutemann went to inspect the damage, and they refused to start until it had been repaired; and it was repaired in time; although the race started well after it was supposed to. The cars were shown the green light while the back half of the field was still in motion (this often happened at Monza and it had happened during the first start); and due to the visible excitement of the start official Andretti and Canadian Gilles Villeneuve jumped the start and were penalised a minute; Lauda went on to take victory in his Alfa-powered Brabham in a shortened race distance; it was getting dark by the time the checkered flag was shown to the Austrian driver. 1979 saw changes to Monza, run off areas were added to the Curva Grande and Lesmo corners and the track was upgraded. Scheckter, now driving for Ferrari, won the race and the Drivers' Championship.

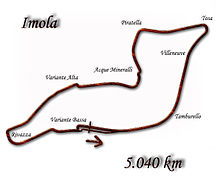

Imola 1980 and Monza's further redevelopments

In 1979, it was announced that the Autodromo Dino Ferrari, also known as Imola, would host the Italian Grand Prix for 1980 while Monza underwent a major upgrade, including building a new pit complex. The Imola circuit had been used for a non-championship event in 1979, and this running of the Italian GP was won by Nelson Piquet.

The Italian Grand Prix returned to Monza for 1981, and it has stayed there ever since. The Imola circuit was not to leave Formula One, it hosted the San Marino Grand Prix from 1981 to 2006. The 1981 Italian Grand Prix was won by rising star Alain Prost, and that race saw Briton John Watson have a huge accident at the second Lesmo Curve which also took out Italian Michele Alboreto. Watson was uninjured in his carbon-fibre McLaren. 1982 was won by Prost's teammate Rene Arnoux; and Prost also won the exciting 1985 event, this time driving a McLaren.

Prost's championship rivals Alboreto (now driving a Ferrari) and Finn Keke Rosberg in a Williams both retired. 1988 saw a memorable win; as McLaren had won every race up to the Italian Grand Prix; Prost had gone out with engine problems and his teammate Ayrton Senna had crashed into a backmarker with two laps to go- and Austrian Gerhard Berger in a Ferrari took victory, followed by Alboreto to make it a Ferrari 1–2. This was particularly memorable because Enzo Ferrari had died a month before this event.

1989 saw Prost win after the Honda engine in Senna's McLaren expired; but Senna took victory the following year. 1991 saw a battle between Senna and the two Williams drivers of Nigel Mansell and Riccardo Patrese. Mansell won, Senna finished 2nd and Patrese went out with gearbox problems. Senna won again in 1992, and 1993 saw Williams drivers Alain Prost and Damon Hill battle hard, and while leading, Prost's engine failed and Hill went on to take victory.

In response to the Imola tragedies in 1994, the second Lesmo curve was slowed down but the race risked being canceled due to the bureaucratic and environmental difficulties of modifying the track. Other changes were made in 1995 at Curva Grande, Variante della Roggia and both Lesmo Corners, which were anticipaded for to create wider runoff areas. 1996 saw Michael Schumacher win for Ferrari, and 1999 saw championship leader Mika Hakkinen crash and the Finn, false to temperament, went behind a few bushes in the circuit and broke down crying. 2000 saw further changes to the circuit, which have stayed since; the Variante Rettifilo was made into a two corner sequence instead of a three corner sequence. The race that year started off tragically, as an accident during the start at the Variante della Roggia resulted in a marshal being struck in the head and chest by a loose wheel from German Heinz-Harald Frentzen's Jordan. 33-year-old Paolo Gislimberti was given a heart massage at the scene, but later died from his injuries. On a more positive note, the decade also started off with a romp of Ferrari victories, winning in 2000 and 2002–2004.

After winning the 2006 Italian Grand Prix, Michael Schumacher announced his retirement from Formula 1 racing at the end of the 2006 season. Kimi Räikkönen replaced him at Ferrari from the start of the 2007 season. At the 2008 Italian Grand Prix, Sebastian Vettel became the youngest driver in history to win a Formula One Grand Prix. Aged 21 years and 74 days, Vettel broke the record set by Fernando Alonso at the 2003 Hungarian Grand Prix by 317 days as he won in wet conditions at Monza.

Vettel led for the majority of the Grand Prix and crossed the finish line 12.5 seconds ahead of McLaren's Heikki Kovalainen. Earlier in the weekend, he had already become the youngest pole sitter, after setting the fastest times in both Q2 and Q3 qualifying stages. His win also gave him the record of youngest podium-finisher. Vettel also won in 2011, after a spectacular pass at the Curva Grande, passing Fernando Alonso on the outside of the big, long curve.

Uncertainty grew over the fact that Monza would continue to host the race as Rome had signed a deal to host Formula One from 2012. On 18 March 2010 however, Bernie Ecclestone and the Monza track managers signed a deal which meant that the race will be held there until at least 2016.[3] In late 2019, work will begin on a bend that will actually bypass the Curva Grande and the first chicane. Drivers will go through a fast part entering the old Pirelli circuit. Work will be completed by 2019.[4]

The 2018 Italian Grand Prix saw the fastest ever qualifying lap, set by Kimi Räikkönen in a Ferrari in a time of 1:19.119 at an average speed of 263.587 km/h.

A total of twelve Italian drivers have won the Italian Grand Prix; ten before World War II and three when it was part of the world championship; most recently Ludovico Scarfiotti won in 1966. Alberto Ascari won the race three times (once before Formula One and twice during the Formula One championship). Elio de Angelis and Riccardo Patrese both won the San Marino Grand Prix in 1985 and 1990 respectively, so they won in the home soil but not in Monza. Both Michael Schumacher and Lewis Hamilton have won it five times and Nelson Piquet has won it four times. Ferrari have won their home Grand Prix 19 times.

Official names

- 1950, 1952–1955, 1957–1959, 1961–1966, 1968–1987, 2007, 2013–2015: Gran Premio d'Italia (no official sponsor)[5]

- 1951: G.P. d'Italia (no official sponsor)[6]

- 1956, 1960, 1967: Gran Premio d'Europa (no official sponsor)[7]

- 1988–1991: Coca-Cola Gran Premio d'Italia[8][9]

- 1992–1996: Pioneer Gran Premio d'Italia[10]

- 1997–2001: Gran Premio Campari d'Italia[11]

- 2002–2006: Gran Premio Vodafone d'Italia[12]

- 2008–2012: Gran Premio Santander d'Italia[13]

- 2016–present: Gran Premio Heineken d'Italia[14]

Winners of the Italian Grand Prix

Multiple winners (drivers)

Drivers in bold are competing in the Formula One championship in the current season.

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship.

A yellow background indicates an event which was part of the pre-war European Championship.

| Wins | Driver | Years won |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | 1996, 1998, 2000, 2003, 2006 | |

| 2012, 2014, 2015, 2017, 2018 | ||

| 4 | 1980, 1983, 1986, 1987 | |

| 3 | 1931, 1932, 1938 | |

| 1949, 1951, 1952 | ||

| 1953, 1954, 1955 | ||

| 1956, 1957, 1959 | ||

| 1973, 1974, 1976 | ||

| 1981, 1985, 1989 | ||

| 2002, 2004, 2009 | ||

| 2008, 2011, 2013 | ||

| 2 | 1933, 1934 | |

| 1934, 1937 | ||

| 1960, 1961 | ||

| 1964, 1967 | ||

| 1965, 1969 | ||

| 1970, 1975 | ||

| 1978, 1984 | ||

| 1990, 1992 | ||

| 1993, 1994 | ||

| 2001, 2005 | ||

| 2007, 2010 |

Multiple winners (constructors)

Teams in bold are competing in the Formula One championship in the current season.

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of any championship.

A yellow background indicates an event which was part of the pre-war European Grand Prix Championship.

A green background indicates an event which was part of the pre-war World Manufacturers' Championship.

| Wins | Constructor | Years won |

|---|---|---|

| 20 | 1949, 1951, 1952, 1960, 1961, 1964, 1966, 1970, 1975, 1979, 1988, 1996, 1998, 2000, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2006, 2010, 2019 | |

| 10 | 1968, 1984, 1985, 1989, 1990, 1992, 1997, 2005, 2007, 2012 | |

| 9 | 1934, 1937, 1954, 1955, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018 | |

| 8 | 1924, 1925, 1931, 1932, 1933, 1947, 1948, 1950 | |

| 6 | 1986, 1987, 1991, 1993, 1994, 2001 | |

| 5 | 1963, 1972, 1973, 1974, 1977 | |

| 3 | 1935, 1936, 1938 | |

| 1962, 1965, 1971 | ||

| 1978, 1980, 1983 | ||

| 2 | 1922, 1923 | |

| 1926, 1928 | ||

| 1953, 1956 | ||

| 1957, 1958 | ||

| 1981, 1982 | ||

| 2011, 2013 |

Multiple winners (engine manufacturers)

Manufacturers in bold are competing in the Formula One championship in the current season.

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of any championship.

A yellow background indicates an event which was part of the pre-war European Grand Prix Championship.

A green background indicates an event which was part of the pre-war World Manufacturers' Championship.

| Wins | Manufacturer | Years won |

|---|---|---|

| 21 | 1949, 1951, 1952, 1960, 1961, 1964, 1966, 1970, 1975, 1979, 1988, 1996, 1998, 2000, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2006, 2008, 2010, 2019 | |

| 14 | 1934, 1937, 1954, 1955, 1997, 2005, 2007, 2009, 2012, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018 | |

| 9 | 1924, 1925, 1931, 1932, 1933, 1947, 1948, 1950, 1978 | |

| 8 | 1968, 1969, 1972, 1973, 1974, 1976, 1977, 1980 | |

| 1981, 1982, 1991, 1993, 1994, 1995, 2011, 2013 | ||

| 6 | 1967, 1986, 1987, 1989, 1990, 1992 | |

| 3 | 1935, 1936, 1938 | |

| 1962, 1965, 1971 | ||

| 2 | 1922, 1923 | |

| 1926, 1928 | ||

| 1953, 1956 | ||

| 1957, 1958 | ||

| 1959, 1963 | ||

| 1984, 1985 | ||

| 1983, 2001 |

* Between 1997–2005 built by ![]() Ilmor, funded by Mercedes

Ilmor, funded by Mercedes

** Built by ![]() Cosworth, funded by Ford

Cosworth, funded by Ford

*** Built by ![]() Porsche

Porsche

Year by year

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of any championship.

A yellow background indicates an event which was part of the pre-war European Championship.

A green background indicates an event which was part of the pre-war World Manufacturers' Championship.

References

- ^ Colin Goodwin. The Racing Driver's Pocket–Book. p. 9. ISBN 9781844861347.

- ^ "The 1933 Monza Grand Prix". grandprix.com. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- ^ "Monza to keep Formula 1's Italian Grand Prix". BBC Sport. BBC. 18 March 2010. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- ^ "Italian Gran Prix History". 23 March 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ 1950, 1952–1955, 1957–1959, 1961–1966, 1968–1987, 2007, 2013–2015 programs:

- "1950 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1952 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1953 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1954 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1955 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1957 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1958 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1959 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1961 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1962 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1963 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1964 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1965 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1966 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1968 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1969 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1970 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1971 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1972 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1973 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1974 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1975 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1976 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1977 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1978 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1979 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1980 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1981 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1982 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1983 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1984 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1985 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1986 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1987 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2007 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2013 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2014 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2015 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "1951 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ 1956, 1960, 1967 programs:

- "1956 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1960 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1967 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ 1988–1990 programs: "1988 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ "1991 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ 1992–1996 programs:

- "1992 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1993 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1994 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1995 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1996 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ 1997–2001 programs:

- "1997 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1998 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1999 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2000 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2001 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ 2002–2006 programs:

- "2002 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2003 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2004 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2005 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2006 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ 2008–2012 programs:

- "2008 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2009 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2010 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2011 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2012 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- ^ 2016–2019 programs:

- "2016 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "Heineken announces global partnership with Formula One Management". Formula1.com. Formula One World Championship Ltd. 9 June 2016. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- "2017 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2018 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2019 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.