Hulder

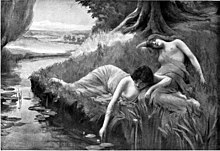

"Huldra's Nymphs" (1909) by Bernard Evans Ward | |

| Grouping | Legendary creature |

|---|---|

| Sub grouping | Humanoid |

| Country | Scandinavia |

| Region | Europe |

A hulder (or huldra) is a seductive forest creature found in Scandinavian folklore. Her name derives from a root meaning "covered" or "secret".[1][2] In Norwegian folklore, she is known as huldra ("the [archetypal] hulder", though folklore presupposes that there is an entire Hulder race and not just a single individual). She is known as the skogsrå "forest spirit" or Tallemaja "pine tree Mary" in Swedish folklore, and ulda in Sámi folklore. Her name suggests that she is originally the same being as the völva divine figure Huld and the German Holda.[3]

The word hulder is only used of a female; a "male hulder" is called a huldrekall and also appears in Norwegian folklore. This being is closely related to other underground dwellers, usually called tusser (sg., tusse). Whereas the female hulder is almost invariably described as incredible, seductive and beautiful, the males of the same race are sometimes said to be hideous, with grotesquely long noses.

Folklore

The hulder is one of several rå (keeper, warden), including the aquatic sjörå or havsfru, later identified with a mermaid, and the bergsrå in caves and mines who made life tough for the poor miners.[citation needed]

More information can be found in the collected Norwegian folktales of Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe.

Relations with humans

The hulders were held to be kind to charcoal burners, watching their charcoal kilns while they rested. Knowing that she would wake them if there were any problems, they were able to sleep, and in exchange they left provisions for her in a special place. A tale from Närke illustrates further how kind a hulder could be, especially if treated with respect (Hellström 1985:15).

Origins

A tale recounts how a woman had washed only half of her children when God came to her cottage; ashamed of the dirty ones, she hid them. God decreed that those she had hidden from him would be hidden from humanity; they became the hulders.[4]

Toponyms

A multitude of places in Scandinavia are named after the Hulders, often places by legend associated with the presence of the "hidden folk". Here are some examples showing the wide distribution of Hulder-related toponyms between the northern and southern reaches of Scandinavia, and the terms usage in different language groups' toponyms.

Danish

- Huldremose (Hulder Bog) is a bog on Djursland, Denmark famous for the discovery of the Huldremose Woman, a bog body from 55BC.

Norwegian

- Hulderheim is southeast on the island Karlsøya, Troms, Norway. The name means "Home of the Hulder".

- Hulderhusan is an area on the southwest of Norway's largest island Hinnøya, whose name means "Houses of the Hulders".

Sámi

- Ulddaidvárri in Kvænangen, Troms (Norway) means "Mountain of the Hulders" in North Sámi.

- Ulddašvággi is a valley southwest of Alta in Finnmark, Norway. The name means "Hulder Valley" in North Sámi. The peak guarding the pass over from the valley to the mountains above has a similar name, Ruollačohkka, meaning "Troll Mountain"—and the large mountain presiding over the valley on its northern side is called Háldi, which is a term similar to the above-mentioned Norwegian rå, that is a spirit or local deity which rules a specific area.

Parallels

The hulder may be connected with the German holda.

See also

- Banshee

- Baobhan sith

- Bloody Mary (folklore)

- Clíodhna

- Dames blanches

- Enchanted Moura

- Glaistig

- Glashtyn

- Huldufólk

- Leanan sídhe

- Neck (water spirit)

- Patasola

- Pontianak (folklore)

- Rusalka

- Samodiva (mythology)

- Sihuanaba

- Siren (mythology)

- Succubus

- Thale (film)

- Weiße Frauen

- White Lady (ghost)

- Wight

- Witte Wieven

References

- ^ AnneMarie Hellström, Jag vill så gärna berätta. ISBN 91-7908-002-2

- ^ Neil Gaiman, American Gods (10th Anniversary Edition). ISBN 978-0-7553-8624-6

- ^ "Nordisk familjebok". runeberg.org (in Swedish). 1 January 1909.

- ^ K. M. Briggs, The Fairies in English Tradition and Literature, p 147 University of Chicago Press, London, 1967