Phoebe (moon)

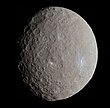

Cassini image of Phoebe | |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | W.H. Pickering |

| Discovery date | 17 March 1899 & 16 August 1898 |

| Designations | |

Designation | Saturn IX |

| Pronunciation | /ˈfiːbiː/[1][2] |

Named after | Φοίβη Phoibē |

| Adjectives | Phoebean /fiːˈbiːən/[3] |

| Orbital characteristics[1] | |

| 12.96 Gm | |

| Eccentricity | 0.1562415 |

| 550.564636 d | |

| Inclination | 173.04° (to the ecliptic) 151.78° (to Saturn's equator) |

| Satellite of | Saturn |

| Group | Norse group |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Dimensions | (218.8±2.8) × (217.0±1.2) × (203.6±0.6) km[4] |

| 106.5±0.7 km[4] | |

| Mass | (8.292±0.010)×1018 kg[4] |

Mean density | 1.638±0.033 g/cm³[4] |

| 0.038–0.050 m/s2[4] | |

| ≈ 0.10 km/s | |

| 9.2735 h (9 h 16 min 25 s ± 3 s)[5] | |

| 152.14° (to orbit)[6] | |

| Albedo | 0.06 |

| Temperature | ≈ 73(?) K |

Phoebe /ˈfiːbiː/ is an irregular satellite of Saturn with a mean diameter of 213 km (132 mi). It was discovered by William Henry Pickering on March 18, 1899[7] from photographic plates that had been taken starting on 16 August 1898 at the Boyden Station of the Carmen Alto Observatory near Arequipa, Peru, by DeLisle Stewart. It was the first satellite to be discovered photographically.

Phoebe was the first target encountered upon the arrival of the Cassini spacecraft in the Saturn system in 2004, and is thus unusually well-studied for an irregular satellite of its size. Cassini's trajectory to Saturn and time of arrival were specifically chosen to permit this flyby.[8] After the encounter and its insertion into orbit, Cassini did not go much beyond the orbit of Iapetus.

Phoebe is roughly spherical and has a differentiated interior. It was spherical and hot early in its history and was battered out of roundness by repeated impacts. It is believed to be a captured centaur that originated in the Kuiper belt.[9] Phoebe is the second largest retrograde satellite in the solar system after Triton [10].

History

Discovery

Phoebe was discovered by William Henry Pickering on 17 March 1899[7] from photographic plates that had been taken starting on 16 August 1898 at the Boyden Observatory near Arequipa, Peru, by DeLisle Stewart.[11][12][13][14][15] It was the first satellite to be discovered photographically.

Naming

Phoebe was named after Phoebe, a Titaness in Greek mythology that was associated with the Moon.[13] It is also designated Saturn IX in some scientific literature. The IAU nomenclature standards have stated that features on Phoebe are to be named after characters in the Greek myth of Jason and the Argonauts. In 2005, the IAU officially named 24 craters[16] (Acastus, Admetus, Amphion, Butes, Calais, Canthus, Clytius, Erginus, Euphemus, Eurydamas, Eurytion, Eurytus, Hylas, Idmon, Iphitus, Jason, Mopsus, Nauplius, Oileus, Peleus, Phlias, Talaus, Telamon and Zetes).

Toby Owen of the University of Hawaii at Manoa, chairman of the International Astronomical Union Outer Solar System Task Group said:

We picked the legend of the Argonauts for Phoebe as it has some resonance with the exploration of the Saturn system by Cassini–Huygens. We can't say that our participating scientists include heroes like Hercules and Atalanta, but they do represent a wide, international spectrum of outstanding people who were willing to take the risk of joining this voyage to a distant realm in hopes of bringing back a grand prize.

Orbit

Saturn · Phoebe · Titan

Phoebe's orbit is retrograde; that is, it orbits Saturn opposite to Saturn's rotation. For more than 100 years, Phoebe was Saturn's outermost known moon, until the discovery of several smaller moons in 2000. Phoebe is almost 4 times more distant from Saturn than its nearest major neighbor (Iapetus), and is substantially larger than any of the other moons orbiting planets at comparable distances.

All of Saturn's regular moons except Iapetus orbit very nearly in the plane of Saturn's equator. The outer irregular satellites follow moderately to highly eccentric orbits, and none are expected to rotate synchronously as all the inner moons of Saturn do (except for Hyperion). See Saturn's satellites' families.

Phoebe ring

The Phoebe ring is one of the rings of Saturn. This ring is tilted 27 degrees from Saturn's equatorial plane (and the other rings). It extends from at least 128 to 207[17] times the radius of Saturn; Phoebe orbits the planet at an average distance of 215 Saturn radii. The ring is about 40 times as thick as the diameter of the planet.[18] Because the ring's particles are presumed to have originated from micrometeoroid impacts on Phoebe, they should share its retrograde orbit,[19] which is opposite to the orbital motion of the next inner moon, Iapetus. Inwardly migrating ring material would thus strike Iapetus's leading hemisphere, creating its two-tone coloration.[20][21][22][23] Although very large, the ring is virtually invisible—it was discovered using NASA's infrared Spitzer Space Telescope.

Physical characteristics

Phoebe is roughly spherical and has a diameter of 213±1.4 km[4] (132 mi), approximately one-sixteenth of that of the Moon. Phoebe rotates every nine hours 16 minutes and it completes a full orbit around Saturn in about 18 months. Its surface temperature is 75 K (−198.2 °C).

Most of Saturn's inner moons have very bright surfaces, but Phoebe's albedo is very low (0.06), as dark as lampblack. The Phoebean surface is extremely heavily scarred, with craters up to 80 kilometres across, one of which has walls 16 kilometres high.[citation needed]

Phoebe's dark coloring initially led to scientists surmising that it was a captured asteroid, as it resembled the common class of dark carbonaceous asteroids.[citation needed] These are chemically very primitive and are thought to be composed of original solids that condensed out of the solar nebula with little modification since then.

However, images from Cassini indicate that Phoebe's craters show a considerable variation in brightness, which indicate the presence of large quantities of ice below a relatively thin blanket of dark surface deposits some 300 to 500 metres (980 to 1,640 ft) thick. In addition, quantities of carbon dioxide have been detected on the surface, a finding that has never been replicated for an asteroid. It is estimated that Phoebe is about 50% rock, as opposed to the 35% or so that typifies Saturn's inner moons. For these reasons, scientists are coming to think that Phoebe is in fact a captured centaur, one of a number of icy planetoids from the Kuiper belt that orbit the Sun between Jupiter and Neptune.[24][25] Phoebe is the first such object to be imaged as anything other than a dot.

Despite its small size, Phoebe is thought to have been a spherical body early in its history, with a differentiated interior, before solidifying and being battered into its current, slightly non-equilibrium shape.[26]

Material displaced from Phoebe's surface by microscopic meteor impacts may be responsible for the dark areas on the surface of Hyperion.[note 1] Debris from the biggest impacts may be the origin of the other moons of Phoebe's group (the Norse group)—all of which are less than 10 km in diameter.

Maps

-

Map of Phoebe's middle latitudes. The higher latitudes have been clipped from the main map, but can be seen in the polar projections.

-

Map of Phoebe's south polar region

-

Map of Phoebe's north polar region

-

3D map showing Phoebe's once spherical shape

Formation

Phoebe formed in the Kuiper belt within three million years after the origin of the Solar System. This was early enough that sufficient radioactive material was available to collapse it into a sphere and stay warm enough to have liquid water for tens of millions of years.[26]

Observation and exploration

Unlike Saturn's other moons, Phoebe was not favorably placed for the Voyager probes. Voyager 2 observed Phoebe for a few hours in September 1981. In the images, taken from a distance of 2.2 million kilometres at low phase angle, the size of Phoebe was approximately 11 pixels and showed bright spots on the otherwise dark surface.

Cassini passed 2,068 kilometres (1,285 mi) from Phoebe on 11 June 2004, returning many high-resolution images, which revealed a scarred surface. Because Voyager 2 had not been able to produce any high quality images of Phoebe, obtaining them was a priority for the Cassini mission[8] and its flight path was deliberately designed to take it close by; otherwise, Cassini would likely not have returned images much better than Voyager's. Because of Phoebe's short rotation period of approximately 9 hours, 17 minutes, Cassini was able to map virtually the entire surface of Phoebe. The close fly-by enabled the mass of Phoebe to be determined with an uncertainty of only 1 in 500.[27]

See also

Notes

References

- ^ "Phoebe". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ The Latin form is 'Phoēbē', with stress on the first 'e' (Phoebe), but no-one proposes that pronunciation for English

- ^ "Phoebean". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ a b c d e f Thomas, P. C. (July 2010). "Sizes, shapes, and derived properties of the saturnian satellites after the Cassini nominal mission" (PDF). Icarus. 208 (1): 395–401. Bibcode:2010Icar..208..395T. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2010.01.025.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Bauer, J.M.; Buratti, B.J.; Simonelli, D.P.; Owen, W.M. (2004). "Recovering the Rotational Lightcurve of Phoebe". The Astronomical Journal. 610 (1): L57–L60. Bibcode:2004ApJ...610L..57B. doi:10.1086/423131.

- ^ Porco CC; et al. (2005-02-25). "Cassini Imaging Science: Initial Results on Phoebe and Iapetus" (PDF). Science. 307 (5713): 1237–1242. Bibcode:2005Sci...307.1237P. doi:10.1126/science.1107981. PMID 15731440.

- ^ a b Kovas, Charlie. "On This Day". What Happened on March 18, 1899. Unknown. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ a b Martinez, Carolina; Brown, Dwayne (2004-06-09). "Cassini Spacecraft Near First Stop in Historic Saturn Tour". Mission News. NASA. Retrieved 2008-03-02.

- ^ Jewitt, David; Haghighipour, Nader (2007). "Irregular Satellites of the Planets: Products of Capture in the Early Solar System" (PDF). Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 45 (1): 261–95. arXiv:astro-ph/0703059. Bibcode:2007ARA&A..45..261J. doi:10.1146/annurev.astro.44.051905.092459. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-09-19.

- ^ https://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/?sat_phys_par

- ^ Pickering EC (1899-03-17). "A New Satellite of Saturn". 49. Harvard College Observatory Bulletin.

- ^ Pickering EC (1899-03-23). "A New Satellite of Saturn". Astronomical Journal. 20 (458): 13. Bibcode:1899AJ.....20...13P. doi:10.1086/103076.

- ^ a b Pickering EC (1899-04-10). "A New Satellite of Saturn". Astrophysical Journal. 9 (4): 274–276. Bibcode:1899ApJ.....9..274P. doi:10.1086/140590.

- ^ Pickering EC (1899-04-29). "A New Satellite of Saturn". Astronomische Nachrichten. 149 (10): 189–192. Bibcode:1899AN....149..189P. doi:10.1002/asna.18991491003. (same as above)

- ^ "A Ninth Satellite to Saturn". The Observatory. 22 (278): 158–159. April 1899. Bibcode:1899Obs....22..158.

- ^ Features on Saturn's moon Phoebe given names, Spaceflight Now, February 24, 2005

- ^ Verbiscer, Anne; Skrutskie, Michael; Hamilton, Douglas (2009-10-07). "Saturn's largest ring". Nature. 461 (7267): 1098–100. Bibcode:2009Natur.461.1098V. doi:10.1038/nature08515. PMID 19812546.

- ^ "The King of Rings". NASA, Spitzer Space Telescope center. 2009-10-07. Retrieved October 7, 2009.

- ^ Cowen, Rob (October 6, 2009). "Largest known planetary ring discovered". Science News.

- ^ Largest ring in solar system found around Saturn, New Scientist

- ^ Mason, J.; Martinez, M.; Balthasar, H. (2009-12-10). "Cassini Closes In On The Centuries-old Mystery Of Saturn's Moon Iapetus". CICLOPS website newsroom. Space Science Institute. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

- ^ Denk, T.; et al. (2009-12-10). "Iapetus: Unique Surface Properties and a Global Color Dichotomy from Cassini Imaging". Science. 327 (5964): 435–439. Bibcode:2010Sci...327..435D. doi:10.1126/science.1177088. PMID 20007863.

- ^ Spencer, J. R.; Denk, T. (2009-12-10). "Formation of Iapetus' Extreme Albedo Dichotomy by Exogenically Triggered Thermal Ice Migration". Science. 327 (5964): 432–435. Bibcode:2010Sci...327..432S. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.651.4218. doi:10.1126/science.1177132. PMID 20007862.

- ^ Johnson, Torrence V.; Lunine, Jonathan I. (2005). "Saturn's moon Phoebe as a captured body from the outer Solar System". Nature. 435 (7038): 69–71. Bibcode:2005Natur.435...69J. doi:10.1038/nature03384. PMID 15875015.

- ^ Martinez, C. (May 6, 2005). "Scientists Discover Pluto Kin Is a Member of Saturn Family". Cassini–Huygens News Releases. Archived from the original on May 1, 2008.

- ^ a b Jia-Rui C. Cook and Dwayne Brown (2012-04-26). "Cassini Finds Saturn Moon Has Planet-Like Qualities". JPL/NASA. Archived from the original on 2012-04-27.

- ^ Roth et al., AAS Paper 05-311

External links

- Phoebe Profile at NASA's Solar System Exploration site

- Cassini–Huygens Multimedia: Images: Moons: Small Moons

- Cassini Pass Reveals Moon Secrets, BBC News, June 14, 2004

- The Planetary Society: Phoebe

- Asaravala, A.; Saturn's Odd Moon Out, Wired, (May 4, 2005)

- NASA: Natural Satellite Physical Parameters

- Cassini images of Phoebe

- Images of Phoebe at JPL's Planetary Photojournal

- Movie of Phoebe's rotation from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

- Phoebe basemap (December 2005) from Cassini images

- Phoebe atlas (March 2006) from Cassini images

- Phoebe nomenclature from the USGS planetary nomenclature page

- Phoebe on T. Denk's Outer Saturnian moons websites