Tourism in Bhutan

Tourism in Bhutan began in 1974, when the Government of Bhutan, in an effort to raise revenue and to promote Bhutanese unique culture and traditions to the outside world, opened its isolated country to foreigners. In 1974 a total of 287 tourists visited the Kingdom of Bhutan. The number of tourists visiting Bhutan increased to 2,850 in 1992, and rose dramatically to 7,158 in 1999.[1] By the late 1980s tourism contributed over US$2 million in annual revenue.

Though open to foreigners, the Bhutanese government is acutely aware of the environmental impact tourists can have on Bhutan's unique and virtually unspoiled landscape and culture. Accordingly, they have restricted the level of tourist activity from the start, preferring higher-quality tourism. Initially, this policy was known as "high value, low volume"[2] tourism. It was renamed in 1999 as "high value, low impact", "a subtle but significant shift" While the low impact is guaranteed through the low number of visitors, it is a requirement to be wealthy to travel Bhutan,[3] which leaves room for critizism and the question whether one has to be wealthy to be a "high value tourist". For tourists a daily fee is imposed of anywhere between US$180 to US$290 per day (or more).[4][5] indicating that the government was prepared to welcome more tourists, although "cultural and environmental" values should be preserved.[citation needed] In 2005 a document called "Sustainable Tourism Development Strategy" "placed greater emphasis on increasing tourist numbers by using the country's culture and environment to promote Bhutan as an exotic niche destination attractive to wealthy tourists".[6]

The Bhutanese government privatised the Bhutan Tourism Corporation (BTC) in October 1991, facilitating private-sector investment and activity. As a result, as of 2018[update] over 75 licensed tourist companies operate in the country.[1] All tourists (group or individual) must travel on a planned, prepaid, guided package-tour or according to a custom-designed travel-program. Most foreigners cannot travel independently in the kingdom. Potential tourists must make arrangements through an officially approved tour operator, either directly or through an overseas agent.

The most important centres for tourism are in Bhutan's capital, Thimphu, and in the western city of Paro, near India. Taktshang, a cliff-side monastery (called the "Tiger's Nest" in English) overlooking the Paro Valley, is one of the country's attractions. This temple is incredibly[quantify] sacred to Buddhists. Housed inside the temple is a cave in which the Buddhist Deity who brought Buddhism to Bhutan meditated for 90 days, battling the demons that inhabited this valley, in order to spread Buddhism. The temple has been standing for well over a thousand years; it has suffered two fires, but the damage has been repaired. Druk Air used to be[when?] the only airline operating flights in Bhutan, however as of 2012[update] the country is serviced by Bhutan Airlines as well.[7][failed verification]

Potential visitors to Bhutan obtain visas through a Bhutanese embassy or consulate in their home country.

Arrivals by country

Most visitors arriving to Bhutan on a short term basis were from the following countries of nationality:[8][9][10] In 2017, the country saw its highest tourist arrival yet at more than 250,000 people. The growth was boosted by the Asia-Pacific market, notably from India, Thailand, Vietnam, Philippines, Australia, Japan, China, Singapore, Bangladesh, Malaysia, Maldives, and South Korea. Western markets also increased, notably from the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, and France. Majority of 'tourists' that came from China were also classified as 'Tibetan refugees'.[11]

| Rank | Country | 2013 | 2015 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 11,550 | 25,380 | 56,210 | |

| 2 | 7,997 | 12,100 | 15,202 | |

| 3 | 4,000 | 7,000 | 10,000 | |

| 4 | 4,000 | 7,399 | 7,298 | |

| 5 | 6,997 | 7,137 | 7,292 | |

| 6 | 4,035 | 2,437 | 4,833 | |

| 7 | 3,527 | 3,778 | 4,177 | |

| 8 | 2,309 | 2,958 | 3,124 | |

| 9 | 2,051 | 2,587 | 3,015 | |

| 10 | 2,770 | 2,498 | 2,297 | |

| 11 | 2,054 | 1,546 | 1,967 | |

| 12 | 2,062 | 1,833 | 1,818 | |

| 13 | 1,572 | 1,563 | 1,501 |

UNESCO Tentative List of Bhutan

In 2012, Bhutan formally listed its tentative sites to the UNESCO World Heritage Centre. It was the first time Bhutan listed its sites to the organization for future inclusion. Eights sites were listed, located in various properties throughout the country.[12]

| Site | Image | Location | Proposed criteria | Year Listed as Tentative Site | Description | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ancient Ruin of Drukgyel Dzong |

|

Paro District | Cultural | 2012 | The site includes the ruins of a fortress-Buddhist monastery built by Tenzin Drukdra in 1649. In 2016, the Bhutanese government announced that the monastery will be rebuilt to its former glory.[13] | [14] |

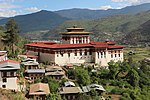

| Dzongs: the centre of temporal and religious authorities (Punakha Dzong, Wangdue Phodrang Dzong, Paro Dzong, Trongsa Dzong and Dagana Dzong) |

|

Multiple | Cultural | 2012 | The site includes five dzongs significant to Bhutanese history, namely, Punakha Dzong, Wangdue Phodrang Dzong, Paro Dzong, Trongsa Dzong and Dagana Dzong. | [15] |

| Sacred Sites associated with Phajo Drugom Zhigpo and his descendants |

|

Multiple | Cultural | 2012 | The site includes Tsedong Phug, Gawa Phug, Langthang Phug, Sengye Phug, Gom Drak, Thukje Drak, Tsechu Drak, Dechen Drak, Taktsang Sengye Samdrub Dzong, Tago Choying Dzong, Lingzhi Jagoe Dzong and Yangtse Thubo Dzong. | [16] |

| Tamzhing Monastery |

|

Bumthang District | Cultural | 2012 | The site is the most important Nyingma gompa in Bhutan. | [17] |

| Royal Manas National Park (RMNP) |

|

Multiple districts | Natural | 2012 | The site is the oldest national park in Bhutan. | [18] |

| Jigme Dorji National Park (JDNP) | Multiple districts | Natural | 2012 | The site is the second largest national park in Bhutan. | [19] | |

| Bumdeling Wildlife Sanctuary |

|

Trashiyangtse District | Cultural | 2012 | The site is an important bird area in the Himalayas. | [20] |

| Sakteng Wildlife Sanctuary (SWS) |

|

Multiple districts | Cultural | 2012 | The site was established to protect a mythical race known as migoi, as well as the wildlife within the site. | [21] |

Criticism of the "High Quality, Low Volume" Principle

While Bhutan is successful in limiting the numbers of tourists who enter the country,[22] with its principle of "High Quality, Low Volume"[23] it can be argued, that a "high quality tourist" needs to be a wealthy tourist, because the hurdle of visiting Bhutan is mainly posed by the high pricing[24] and not by actual interest or mindfulness.[25]

See also

References

- ^ a b Dorji, Tandi. "Sustainability of Tourism in Bhutan" (PDF). Digital Himalaya. Retrieved August 10, 2008.

- ^ High Value Low Volume. KuenselOnline (2015-08-21). Retrieved on 2020-07-28.

- ^ Kent Schroeder, Politics of Gross National Happiness: Governance and Development in Bhutan, Cham (Switzerland): Palgrave Macmillan, 2018, 54–55.

- ^ How to get Bhutan tourist visa cost and requirement. Bhutantraveloperator.com. Retrieved on 2020-07-28.

- ^

Schroeder, Kent (2017). "The Last Shangri-La?". Politics of Gross National Happiness: Governance and Development in Bhutan. Cham (Zug): Springer. p. 55. ISBN 9783319653884. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

To drive increased tourism revenues, the earlier approach of 'high value, low volume' was replaced by 'high value, low impact'. This represented a subtle but significant shift.

- ^ Kent Schroeder, Politics of Gross National Happiness: Governance and Development in Bhutan, Cham (Switzerland): Palgrave Macmillan, 2018, 54–55.

- ^ Ionides, Nicholas (9 April 2008). "Bhutan's Druk Air looks to expand". Airline Business. Retrieved 2008-08-10.

- ^ Tourism Council of Bhutan (2014) BHUTAN TOURISM MONITOR. Annual Report 2013.

- ^ Tourism Council of Bhutan (2016) "BHUTAN TOURISM MONITOR. Annual Report 2015" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-10-09. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- ^ Tourism Council of Bhutan (2017) "BHUTAN TOURISM MONITOR. Annual Report 2016" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-07-12. Retrieved 2017-05-30.

- ^ Bhutan saw highest number of tourists last year – BBS | BBS. Bbs.bt (2018-04-13). Retrieved on 2020-07-28.

- ^ Bhutan. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved on 2020-07-28.

- ^ Drukyul’s victory rises to The Gyalsey – KuenselOnline. Kuenselonline.com (2016-02-07). Retrieved on 2020-07-28.

- ^ Ancient Ruin of Drukgyel Dzong. UNESCO World Heritage Centre (2020-07-09). Retrieved on 2020-07-28.

- ^ Dzongs: the centre of temporal and religious authorities (Punakha Dzong, Wangdue Phodrang Dzong, Paro Dzong, Trongsa Dzong and Dagana Dzong). UNESCO World Heritage Centre (2020-07-09). Retrieved on 2020-07-28.

- ^ Sacred Sites associated with Phajo Drugom Zhigpo and his descendants. UNESCO World Heritage Centre (2020-07-09). Retrieved on 2020-07-28.

- ^ Tamzhing Monastery. UNESCO World Heritage Centre (2020-07-09). Retrieved on 2020-07-28.

- ^ Royal Manas National Park (RMNP). UNESCO World Heritage Centre (2020-07-09). Retrieved on 2020-07-28.

- ^ Jigme Dorji National Park (JDNP). UNESCO World Heritage Centre (2020-07-09). Retrieved on 2020-07-28.

- ^ Bumdeling Wildlife Sanctuary. UNESCO World Heritage Centre (2020-07-09). Retrieved on 2020-07-28.

- ^ Sakteng Wildlife Sanctuary (SWS). UNESCO World Heritage Centre (2020-07-09). Retrieved on 2020-07-28.

- ^ Bhutan saw highest number of tourists last year – BBS | BBS. Bbs.bt (2018-04-13). Retrieved on 2020-07-28.

- ^ Nyaupane, Gyan P. and Timothy, Dallen (2016) "Bhutan’s Low-volume, High-yield Tourism: The Influence of Power and Regionalism". Travel and Tourism Research Association: Advancing Tourism Research Globally.

- ^ Why Is Bhutan So Expensive? What Costs The Most. Tibettravel.org (2011-12-19). Retrieved on 2020-07-28.

- ^ Schroeder, Kent (2017). "The Last Shangri-La?". Politics of Gross National Happiness: Governance and Development in Bhutan. Cham (Zug): Springer. p. 55. ISBN 9783319653884. Retrieved 25 January 2020. To drive increased tourism revenues, the earlier approach of 'high value, low volume' was replaced by 'high value, low impact'. This represented a subtle but significant shift.

External links

Bhutan travel guide from Wikivoyage

Bhutan travel guide from Wikivoyage- Tourism Council of Bhutan (Official Website)

- Tourism Council of Bhutan approved DMC

- Ura Yakchoe Festival