Yellow Peril

The Yellow Peril (also the Yellow Terror and the Yellow Specter) is a racist color-metaphor that misrepresents East Asians as an existential danger to the Western world.[2] As a psycho-cultural perception of menace from the Eastern world, fear of the Yellow Peril is racial, not national, a fear derived not from concern with a specific source of danger or from any one people or country, but from a vaguely ominous, existential fear of the faceless, nameless hordes of yellow people opposite the Western world. As a form of xenophobia, the Yellow Terror is fear of the Oriental non-white Other, a racialist fantasy presented in the book The Rising Tide of Color Against White World-Supremacy (1920), by Lothrop Stoddard.[3]

The racist ideology of the Yellow Peril derives from a "core imagery of apes, lesser men, primitives, children, madmen, and beings who possessed special powers", which are cultural representations of colored people that originated in the Greco-Persian Wars (499–449 BC), between Ancient Greece and the Persian Empire; centuries later, Western imperialist expansion adduced East Asians as the Yellow Peril.[3][4]

In the late 19th century, the Russian sociologist Jacques Novikow coined the term in the essay "Le Péril Jaune" ("The Yellow Peril", 1897), which racism Kaiser Wilhelm II (r. 1888–1918) used to encourage the European empires to invade, conquer, and colonize China.[5] To that end, using the Yellow Peril ideology, the Kaiser misrepresented Japan's victory in the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905) as an Asian racial threat to white Western Europe, and also misrepresented China and Japan as in alliance to conquer, subjugate, and enslave the Western world.

The sinologist Wing-Fai Leung explained the fantastic origins of the term and the racialist ideology: "The phrase yellow peril (sometimes yellow terror or yellow specter) . . . blends Western anxieties about sex, racist fears of the alien Other, and the Spenglerian belief that the West will become outnumbered and enslaved by the East."[6] The academic Gina Marchetti identified the psycho-cultural fear of East Asians as "rooted in medieval fears of Genghis Khan and the Mongol invasions of Europe [1236–1291], the Yellow Peril combines racist terror of alien cultures, sexual anxieties, and the belief that the West will be overpowered and enveloped, by the irresistible, dark, occult forces of the East";[7]: 2 hence, to oppose Japanese imperial militarism, the West expanded the Yellow Peril ideology to include the Japanese people. Moreover, in the late-19th and early-20th centuries, writers developed the Yellow Peril literary topos into codified, racialist motifs of narration, especially in stories and novels of ethnic conflict in the genres of invasion literature, colonial adventure, and science fiction.[8][9]

Origins

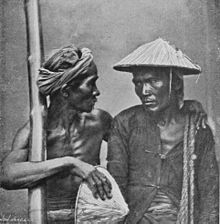

The racist and cultural stereotypes of the Yellow Peril originated in the late 19th century, when Chinese workers (people of different skin-color, physiognomy, language and culture) legally immigrated to Australia, Canada, the U.S. and New Zealand, where their work ethic inadvertently provoked a racist backlash against Chinese communities, for agreeing to work for lower wages than did the local white populations. In 1870, the French Orientalist and historian Ernest Renan warned Europeans of Eastern danger to the Western world; yet Renan had meant the Russian Empire (1721–1917), a country and nation whom the West perceived as more Asiatic than European.[10][11]

Imperial Germany

Since 1870, the Yellow Peril ideology gave concrete form to the anti-East Asian racism of Europe and North America.[10] In central Europe, the Orientalist and diplomat Max von Brandt advised Kaiser Wilhelm II that Imperial Germany had colonial interests to pursue in China.[12]: 83 Hence, the Kaiser used the phrase die Gelbe Gefahr (The Yellow Peril) to specifically encourage Imperial German interests and justify European colonialism in China.[13]

In 1895, Germany, France, and Russia staged the Triple Intervention to the Treaty of Shimonoseki (17 April 1895), which concluded the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), in order to compel Imperial Japan to surrender their Chinese colonies to the Europeans; that geopolitical gambit became an underlying casus belli of the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05).[12]: 83 [14] The Kaiser justified the Triple Intervention to the Japanese empire with racialist calls-to-arms against non-existent geopolitical dangers of the "yellow race" against the "white race" of Western Europe.[12]: 83

To justify European cultural hegemony, the Kaiser used the allegorical lithograph Peoples of Europe, Guard Your Most Sacred Possessions (1895), by Hermann Knackfuss, to communicate his geopolitics to other European monarchs. The lithograph depicts Germany as the leader of Europe,[10][15] personified as a "prehistoric warrior-goddesses being led by the Archangel Michael against the 'yellow peril' from the East", which is represented by "dark cloud of smoke [upon] which rests an eerily calm Buddha, wreathed in flame".[16]: 31 [17]: 203 Politically, the Knackfuss lithograph allowed Kaiser Wilhelm II to believe he prophesied the imminent race war that would decide global hegemony in the 20th century.[16]: 31

Imperial Russia

In the late 19th century, with the Treaty of Saint Petersburg (1881), the Qing dynasty (1644–1912) China recovered the eastern portion of the Ili River basin (Zhetysu), which Russia had occupied for a decade, since the Dungan Revolt (1862–77).[18][19][20] In that time, the mass communications media of the West misrepresented China as an ascendant military power, and applied Yellow Peril ideology to evoke racist fears that China would conquer Western colonies, such as Australia.[21]

United States

In 1870s California, despite the Burlingame Treaty (1868) allowing legal migration of unskilled laborers from China, the native white working-class demanded that the U.S government cease the immigration of "filthy yellow hordes" of Chinese people who took jobs from native-born white-Americans, especially during an economic depression.[3] In 1854, as editor of the New-York Tribune, Horace Greeley published "Chinese Immigration to California" an editorial opinion supporting the popular demand for the exclusion of Chinese workers and people from California. Without using the term "yellow peril", Greeley compared the arriving coolies to the African slaves who survived the Middle Passage; yet Greeley praised the minority of Christian coolies arriving from China:

But of the remainder, what can be said? They are for the most part an industrious people, forbearing and patient of injury, quiet and peaceable in their habits; say this and you have said all good that can be said of them. They are uncivilized, unclean, and filthy beyond all conception, without any of the higher domestic or social relations; lustful and sensual in their dispositions; every female is a prostitute of the basest order; the first words of English that they learn are terms of obscenity or profanity, and beyond this they care to learn no more.

— New York Daily Tribune, Chinese Immigration to California, 29 September 1854, p. 4.[22]

In Los Angeles, Yellow Peril racism provoked the Chinese Massacre of 1871, wherein 500 white men lynched 20 Chinese men in the Chinatown ghetto. Throughout the 1870s and 1880s, the leader of the Workingmen's Party of California, the demagogue Denis Kearney, successfully applied Yellow Peril ideology to his politics against the press, capitalists, politicians, and Chinese workers,[23] and concluded his speeches with the epilogue: "and whatever happens, the Chinese must go!"[24][25]: 349 The Chinese people also were specifically subjected to moralistic panics about their use of opium, and how their use made opium popular among white people.[26] As in the case of Irish-Catholic immigrants, the popular press misrepresented Asian peoples as culturally subversive, whose way of life would diminish republicanism in the U.S.; hence, racist political pressure compelled the U.S. government to legislate the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882), which remained the effective immigration-law until 1943.[3] Moreover, following the example of Kaiser Wilhelm II's use of the term in 1895, the popular press in the U.S. adopted the phrase "yellow peril" to identify Japan as a military threat, and to describe the many emigrants from Asia.[27]

The Boxer Rebellion

In 1900, the anti-colonial Boxer Rebellion (August 1899 – September 1901) reinforced the racist stereotypes of East Asians as a Yellow Peril to white people. The Society of the Righteous and Harmonious Fists (the Boxers) was a xenophobic martial-arts organization who blamed the problems of China on the presence of Western colonies in China proper. The Boxers sought to save China by killing every Western colonist and Chinese Christian – Westernized Chinese people.[28]: 350 In early summer of 1900, Prince Zaiyi allowed the Boxers into Beijing, to kill Western colonists and Chinese Christians, in siege to the foreign legations.[28]: 78–79 Afterwards, Ronglu, Qing Commander-in-Chief, and Yikuang (Prince Qing), resisted and expelled the Boxers from Beijing after days of fighting.

Western perception

Most of the victims of the Boxer Rebellion were Chinese Christians, but the massacres of Chinese people were of no interest to the West, who demanded Asian blood to avenge the Western colonists killed by rebellious Chinese natives.[29] In response, Imperial Great Britain, the U.S., and Imperial Japan, Imperial France, Imperial Russia, and Imperial Germany, Austria–Hungary and Italy formed the Eight-Nation Alliance and despatched an international military expeditionary force to end the Siege of the International Legations in Beijing.

The Russian press presented the Boxer Rebellion in racialist and religious terms, as a cultural war between White Holy Russia and Yellow Pagan China. The press further supported the Yellow Peril apocalypse with quotations from the Sinophobic poems of the philosopher Vladimir Solovyov.[30]: 664 Likewise in the press, the aristocracy demanded action against the Asian threat; Prince Sergei Nikolaevich Trubetskoy urged Imperial Russia and other European monarchies to jointly partition China, and end the Yellow Peril to Christendom.[30]: 664–665 Hence, on 3 July 1900, in response to the Boxer Rebellion, Russia expelled the Chinese community (5,000 people) from Blagoveshchensk; then, during the 4–8 July period, the Tsarist police, Cossack cavalry, and local vigilantes killed thousands at the Amur River.[31]

In the West, news of Boxer atrocities against Western colonists stirred anti-Asian racism in Europe and North America, where it was perceived as a race war, between the yellow race and the white race. In that vein,The Economist warned in 1905 that:

The history of the Boxer movement contains abundant warnings, as to the necessity of an attitude of constant vigilance, on the part of the European Powers, when there are any symptoms that a wave of nationalism is about to sweep over the Celestial Empire.[29]

Hence, 61 years later, in 1967, during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), Red Guard shouting “Kill, kill”, attacked the British embassy and beat the diplomats. A diplomat remarked that the Boxers had used the same chant.[29]

Exhortation to barbarism

On 27 July 1900, Kaiser Wilhelm II gave the racist Hunnenrede (Hun speech) exhorting his soldiers to barbarism; that Imperial German soldiers depart Europe for China and suppress the Boxer Rebellion, by acting like "Huns" and committing atrocities against the Chinese (Boxer and civilian):[17]: 203

When you come before the enemy, you must defeat him, pardon will not be given, prisoners will not be taken! Whoever falls into your hands will fall to your sword! Just as a thousand years ago the Huns, under their King Attila, made a name for themselves with their ferocity, which tradition still recalls; so may the name of Germany become known in China in such a way that no Chinaman will ever dare look a German in the eye, even with a squint![17]: 14

Fearful of harm to the public image of Imperial Germany, the Auswärtiges Amt (Foreign Office) published a redacted version of the Hun Speech, expurgated of the exhortation to racist barbarism. Annoyed by Foreign-Office censorship, the Kaiser published the unexpurgated Hun Speech, which "evoked images of a Crusade and considered the current crisis [the Boxer Rebellion] to amount to a war between Occident and Orient." Yet that "elaborate accompanying music, and the new ideology of the Yellow Peril stood in no relation to the actual possibilities and results" of geopolitical policy based upon racist misperception.[33]: 96

Barbaric policy

The Kaiser ordered the expedition-commander, Field Marshal Alfred von Waldersee, to behave barbarously, because the Chinese were, "by nature, cowardly, like a dog, but also deceitful".[33]: 99 In that time, the Kaiser's best friend, Prince Philip von Euenburg wrote to another friend that the Kaiser wanted to raze Beijing, and kill the populace to avenge the murder of Baron Clemens von Ketteler, Imperial Germany's minister to China.[17]: 13 Only the Eight-Nation Alliance's refusal of barbarism to resolve the siege of the legations saved the Chinese populace of Beijing from the massacre recommended by Imperial Germany.[17]: 13 In August 1900, an international military-force of Russian, Japanese, British, French, and American soldiers captured Beijing, before the German force arrived to the city.[33]: 107

Vengeance

The Eight-Nation Alliance sacked Beijing in vengeance for the Boxer Rebellion; the magnitude of the rape, pillaging, and burning indicated "a sense that the Chinese were less than human" to the Western militaries.[28]: 286 About the sacking of the city, an Australian colonist said: "The future of the Chinese is a fearful problem. Look at the frightful sights one sees in the streets of Peking. ... See the filthy, tattered rags they wrap around them. Smell them as they pass. Hear of their nameless immorality. Witness their shameless indecency, and picture them among your own people – Ugh! It makes you shudder!"[28]: 350

British admiral Roger Keyes recalled that: "Every Chinaman ... was treated as a Boxer, by the Russian and French troops, and the slaughter of men, women, and children in retaliation was revolting".[28]: 284 The American missionary Luella Miner reported that "the conduct of the Russian soldiers is atrocious, the French are not much better, and the Japanese are looting and burning without mercy. Women and girls, by the hundreds, have committed suicide to escape a worse fate at the hands of Russian and Japanese brutes."[28]: 284

British soldiers threatened to kill a Chinese old man, unless he gave them his treasure. On learning he had no treasure, a rifleman prepared to bayonet the old man dead.[28]: 284 That rifleman was stopped by another soldier, who told him: "No, not that way! I'm going to shoot him. I've always had a longing to see what sort of wound a dum-dum [bullet] will make, and by Christ, I am going to try one on this blasted Chink!"[28]: 284 After shooting the Chinese old man in the face, the British soldier exclaimed: "Christ, the dum-dum has blown the back out of his bloody nut!"[28]: 284 Moreover, the British journalist George Lynch said, "there are things that I must not write, and that may not be printed in England, which would seem to show that this Western civilization of ours is merely a veneer over savagery".[28]: 285

Barbaric praxis

The German expedition of Field Marshal Waldersee arrived in China on 27 September 1900, after the military defeat of the Boxer Rebellion by the Eight Nation Alliance; yet he launched 75 punitive raids into northern China to search for and destroy the remaining Boxers. The punitive German soldiers killed more peasants than Boxer guerrillas, because, by autumn 1900, the Society of the Righteous and Harmonious Fists posed no threat, military or political.[33]: 109 On 19 November 1900, the Kaiser's military gambit in China was criticized as shameful to Germany; in the Reichstag, the German Social Democrat politician August Bebel criticized the imperial war against the Boxers:

No, this is no crusade, no holy war; it is a very ordinary war of conquest. ... A campaign of revenge as barbaric as has never been seen in the last centuries, and not often at all in History ... not even with the Huns, not even with the Vandals. ... That is not a match for what the German and other troops of foreign powers, together with the Japanese troops, have done in China.[33]: 97

Cultural fear

The political praxis of Yellow Peril racism features a call for apolitical racial unity among the White peoples of the world. To resolve a contemporary problem (economic, social, political) the racialist politician calls for White unity against the non-white Other who threatens Western civilisation from distant Asia. Despite the Western powers' military defeat of the anti-colonial Boxer Rebellion, Yellow Peril fear of Chinese nationalism became a cultural factor among white people: That "the Chinese race" mean to invade, vanquish, and subjugate Christian civilisation in the Western world.[28]: 350–351

In July 1900, the Völkisch movement intellectual Houston Stewart Chamberlain, the "Evangelist of Race", gave his racialist perspective of the cultural meaning of the Boer War (1899–1902) in relation to the cultural meaning of the Boxer Rebellion: "One thing I can clearly see, that is, that it is criminal for Englishmen and Dutchmen to go on murdering each other, for all sorts of sophisticated reasons, while the Great Yellow Danger overshadows us white men, and threatens destruction."[34]: 357

Racial annihilation

The Darwinian threat

The Yellow Peril racialism of the Austrian philosopher Christian von Ehrenfels proposed that the Western world and the Eastern world were in a Darwinian racial struggle for domination of the planet, which the yellow race was winning.[35]: 258 That monogamy was a legalistic hindrance to global white-supremacy, for limiting a genetically superior white man to father children with only one woman; that in polygamy, the yellow race had greater reproductive advantage, for permitting a genetically superior Asian man to father children with many women.[35]: 258–261

Ehrenfels said that the Chinese were an inferior race of people whose Oriental culture lacked "all potentialities . . . determination, initiative, productivity, invention, and organizational talent" supposedly innate to the white cultures of the West.[35]: 263 Despite having dehumanised the Chinese into an essentialist stereotype of physically listless and mindless Asians, von Ehrenfels's cultural cognitive dissonance allowed praising Japan as a first-rate imperial military power whose inevitable conquest of continental China would produce improved breeds of Chinese people. That the Japanese' selective breeding with "genetically superior" Chinese women would engender a race of "healthy, sly, cunning coolies", because the Chinese are virtuosos of sexual reproduction.[35]: 263 The gist of von Ehrenfels's nihilistic racism was that Asian conquest of the West equalled White racial-annihilation; Continental Europe subjugated by a genetically superior Sino–Japanese army consequent to a race war that the West (imperial and democratic) would fail to thwart or win.[35]: 263

Polygamous patriarchy

To resolve the population imbalance between the Eastern world and the Western world, in favour of White people, von Ehrenfels proposed root changes to the mores (social and sexual norms) of the Christian societies of Western European. The state would control human sexuality through polygamy, to ensure the continual procreation of numerically and genetically superior populations of White people. In such a patriarchal society, only high-status White men of known genetic-status would have the legal right to reproduce.[35]: 261–262 Despite such radical social engineering of men's sexual behavior, White women remained monogamous by law; their lives dedicated to the breeding functions of wife and mother.[35]: 261–262

In von Ehrenfels's polygamous patriarchy, fertile women reside and live their daily lives in communal barracks, where they collectively rear their many children. To fulfil her reproductive obligations to the state, each woman is assigned a husband only for reproductive sexual intercourse.[35]: 261–262 That a White man's socio-economic status and genetic classification determine the number of procreative wives he can afford, and so ensure that only the "social winners" reproduce, within a racial caste.[35]: 262 To ensure worldwide White supremacy, von Ehrenfels's polygamous patriarchy eliminates romantic love (marriage) from sexual intercourse, and thus reduces man–woman sexual relations to a transaction of mechanistic reproduction.[35]: 262

Race war

To end the threat of the Yellow Peril to the Western world, von Ehrenfels proposed White racial unity among the nations of the West, in order to jointly prosecute a pre-emptive war of ethnic conflicts to conquer Asia, before it became militarily infeasible. Then establish a worldwide racial hierarchy organized as an hereditary caste system, headed by the White race in each conquered country of Asia.[35]: 264 That an oligarchy of the Aryan White people would form, populate, and lead the racial castes of the ruling class, the military forces, and the intelligentsia; and that in each conquered country, the Yellow and the Black races would be slaves, the economic base of the worldwide racial hierarchy.[35]: 264

The Aryan society that von Ehrenfels proposed in the early 20th century, would be in the far future of the Western world, realized after defeating the Yellow Peril and the other races for control of the Earth, because "the Aryan will only respond to the imperative of sexual reform when the waves of the Mongolian tide are lapping around his neck".[35]: 263 As a racialist, von Ehrenfels characterized the Japanese military victory in the Russo-Japanese War (1905) as an Asian victory against the white peoples of the Christian West, a cultural failure which indicated "the absolute necessity of a radical, sexual reform for the continued existence of the Western races of man . . . [The matter of White racial survival] has been raised from the level of discussion to the level of a scientifically proven fact".[35]: 263

Sublimated Anti-Semitism

In Sex, Masculinity, and the 'Yellow Peril': Christian von Ehrenfels' Program for a Revision of the European Sexual Order, 1902–1910 (2002), the historian Edward Ross Dickinson said that von Ehrenfels always used metaphors of deadly water to express Yellow Peril racism — a flood of Chinese people upon the West; a Chinese torrent of mud drowning Europe; the Japanese are a polluting liquid — because white Europeans would be unaware and unresponsive to the demographic threat until the waves of Asians reached their necks.[35]: 271 As a man of his time, von Ehrenfels likely suffered the same sexual anxieties about his masculinity that were suffered by his right-wing contemporaries, whose racialist works the historian Klaus Theweleit examined, and noted that only von Ehrenfels psychologically projected his sexual self-doubt into Yellow Peril racism, rather than the usual cultural hatreds of Judeo-Bolshevism, then the variety of anti-Semitism popular in Germany during the early 20th century.[35]: 271

Theweleit also noted that, during the European interwar period (1918–1939), the racialist works of the Freikorps mercenaries featured deadly-water metaphors when the only available peacetime enemies were "The Jews" and "The Communists", whose cultural and political existence threatened the manichean worldview of right-wing Europeans.[35]: 271 As such, the psychologically insecure Freikorps fetishized masculinity and were keen to prove themselves "hard men" through the political violence of terrorism against Jews and Communists; thus, the deadly-water defense mechanism against the adult emotional intimacy (romantic love, eroticism, sexual intercourse) and consequent domesticity that naturally occur between men and women.[35]: 271

Xenophobia

Germany and Russia

From 1895, the Kaiser's government used Yellow Peril ideology to portray Imperial Germany as defender of the West against conquest from the East.[36]: 210 In pursuing the policies of Weltpolitik, by which Germany would become the dominant imperial power of the world, the Kaiser manipulated public opinion, the government, and other monarchs.[37] In a letter to Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, the Kaiser said: "It is clearly the great task of the future for Russia to cultivate the Asian continent, and defend Europe from the inroads of the Great Yellow Race".[16]: 31 In The Bloody White Baron (2009), the historian James Palmer explains the sociocultural background of 19th-century Europe from which Yellow Peril ideology originated and flourished:

The 1890s had spawned in the West the specter of the "Yellow Peril", the rise to world dominance of the Asian peoples. The evidence cited was Asian population growth, immigration to the West (America and Australia in particular), and increased Chinese settlement along the Russian border. These demographic and political fears were accompanied by a vague and ominous dread of the mysterious powers supposedly possessed by the initiates of Eastern religions. There is a striking German picture of the 1890s, depicting the dream that inspired Kaiser Wilhelm II to coin the term "Yellow Peril", that shows the union of these ideas. It depicts the nations of Europe, personified as heroic, but vulnerable, female figures guarded by the Archangel Michael, gazing apprehensively towards a dark cloud of smoke in the East, in which rests an eerily calm Buddha, wreathed in flame. . . .

Combined with this was a sense of the slow sinking of the Abendland, the "Evening Land" of the West. This would be put most powerfully, by thinkers such as Oswald Spengler in The Decline of the West (1918) and the Prussian philosopher Moeller van den Bruck, a Russophone obsessed with the coming rise of the East. Both called for Germany to join the "young nations" of Asia through the adoption of such supposedly Asiatic practices as collectivism, "inner barbarism", and despotic leadership. The identification of Russia with Asia would eventually overwhelm such sympathies, instead leading to a more-or-less straightforward association of Germany with the values of "The West", against the "Asiatic barbarism" of Russia. That was most obvious during the Nazi era [1933–1945], when virtually every piece of anti–Russian propaganda talked of the "Asiatic millions" or "Mongolian hordes", which threatened to over-run Europe, but the identification of the Russians as Asian, especially as Mongolian, continued well into the Cold War era [1917–1991].[16]: 30–31

As his cousin, Kaiser Wilhelm knew that Tsar Nicholas shared his anti-Asian racism and believed he could persuade the Tsar to abrogate the Franco-Russian Alliance (1894) and then to form a German–Russian alliance against Britain.[38]: 120–123 In manipulative pursuit of Imperial German Weltpolitik "Wilhelm II's deliberate use of the 'yellow peril' slogan was more than a personal idiosyncrasy, and fitted into the general pattern of German foreign policy under his reign, i.e. to encourage Russia's Far Eastern adventures, and later to sow discord, between the United States and Japan. Not the substance, but only the form, of Wilhelm II's 'yellow peril' propaganda disturbed the official policy of the Wilhelmstrasse."[39]

European Collective Memory of Mongols

In the 19th century, the racial and cultural stereotypes of Yellow Peril ideology colored German perceptions of Russia as a nation more Asiatic that European.[16]: 31 The European folk memory of the 13th-century Mongol invasion of Europe made the word Mongol a cultural synonym for the "Asian culture of cruelty and insatiable appetite for conquest", which was especially personified by Genghis Khan, leader of the Orda, the Mongol Horde.[16]: 57–58

Despite that justifying historical background, Yellow Peril racism was not universally accepted in the societies of Europe. French intellectual Anatole France said that Yellow Peril ideology was to be expected from a racist man such as the Kaiser. Inverting the racist premise of Asian invasion, France showed that European imperialism in Asia and Africa indicated that the European White Peril was the true threat to the world.[10] In his essay "The Bogey of the Yellow Peril" (1904), the British journalist Demetrius Charles Boulger said the Yellow Peril was racist hysteria for popular consumption.[10] Asian geopolitical dominance of the world is "the prospect, placed before the uninstructed reading public, is a revival of the Hun and Mongol terrors, and the names of Attila and Genghis are set out in the largest type to create feelings of apprehension. The reader is assured, in the most positive manner, that this is the doing of the enterprising nation of Japan".[40]: 225 Throughout the successful imperial intrigues facilitated by Germany's Yellow Peril ideology, the Kaiser's true geopolitical target was Britain.[40]: 225

United Kingdom

Although the Chinese were considered a civilized people in 18th-century Britain, 19th century British imperial expansion facilitated racialist hostility towards Asians. The Chinese people were stereotyped as an inherently depraved and corrupt people.[41] Still, there were exceptions to popular racism of the Yellow Peril. In May 1890, William Ewart Gladstone criticized anti-Chinese immigration laws in Australia for penalizing their virtues of hard work (diligence, thrift and integrity), instead of penalizing their vices (gambling and opium smoking).[42]: 25

Cultural temper

In 1904, in a meeting about the Russo–Japanese War, King Edward VII heard the Kaiser complain that the Yellow Peril is "the greatest peril menacing ... Christendom and European civilization. If the Russians went on giving ground, the yellow race would, in twenty years time, be in Moscow and Posen".[43] The Kaiser undiplomatically criticized the British for siding with Japan against Russia, suggesting "race treason" as a motive. In reply to the Kaiser, King Edward said he "could not see it. The Japanese were an intelligent, brave and chivalrous nation, quite as civilized as the Europeans, from whom they only differed by the pigmentation of their skin".[43]

The first British usage of the Yellow Peril phrase was in the Daily News (21 July 1900) report describing the Boxer Rebellion as "the yellow peril in its most serious form".[41] Then, the racism of British Sinophobia, the fear of Chinese people, did not include all Asians since Britain had sided with Japan during the Russo–Japanese War, but France and Germany supported Russia.[44]: 91 The reports of one British military observer, Captain William Pakenham "tended to depict Russia as his enemy, not just Japan".[44]: 91

About pervasive Sinophobia in Western culture, in The Yellow Peril: Dr Fu Manchu & the Rise of Chinaphobia (2014), historian Christopher Frayling noted:

In the early decades of the 20th century, Britain buzzed with Sinophobia. Respectable middle-class magazines, tabloids and comics, alike, spread stories of ruthless Chinese ambitions to destroy the West. The Chinese master-criminal (with his "crafty yellow face twisted by a thin-lipped grin", dreaming of world domination) had become a staple of children's publications. In 1911, "The Chinese in England: A Growing National Problem" an article distributed around the Home Office, warned of "a vast and convulsive Armageddon to determine who is to be the master of the world, the white or yellow man." After the First World War, cinemas, theater, novels, and newspapers broadcast visions of the "Yellow Peril" machinating to corrupt white society. In March 1929, the chargé d'affaires, at London's Chinese legation, complained that no fewer than five plays, showing in the West End, depicted Chinese people in "a vicious and objectionable form".[45]

Moralistic panic

The British popular imagination portrayed the Limehouse district of London as a center of moral depravity and vice, i.e. sexual prostitution, opium smoking, and gambling.[41][45] The popular press warned of the dangers of miscegenation, of Chinese men marrying British women as a racial threat to white Britain, and warned that Triad gangsters kidnapped British women into white slavery, "a fate worse than death" in Western popular culture.[46] In 1914, at the start of the First World War, the Defence of the Realm Act was amended to include the smoking of opium as proof of moral depravity that merited deportation, a legalistic pretext for deporting the Chinese inhabitants of Britain.[46] That anti-Chinese moral panic derived from the social reality that British women were financially independent by way of war-production jobs, which allowed them the sexual freedom of men, a cultural threat to Britain's patriarchal society.[47] Hence, Yellow Peril racism was the psychological projection of European cultural and sexual prejudices against miscegenation onto the Chinese communities as seducing British women into libertinism.[47]

United States

19th century

In the U.S., Yellow Peril xenophobia was legalized with the Page Act of 1875, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, and the Geary Act of 1892. The Chinese Exclusion Act replaced the Burlingame Treaty (1868), which had encouraged Chinese migration, and provided that "citizens of the United States in China, of every religious persuasion, and Chinese subjects, in the United States, shall enjoy entire liberty of conscience, and shall be exempt from all disability or persecution, on account of their religious faith or worship, in either country", withholding only the right of naturalized citizenship.

In the Western U.S., the frequency with which racists lynched Chinese people originated the phrase, "Having a Chinaman's chance in Hell", meaning "no chance at all" of surviving a false accusation.[48] In 1880, the Yellow Peril pogrom of Denver featured the lynching of a Chinese man and the destruction of the local Chinatown ghetto.[48] In 1885, the Rock Springs massacre of 28 miners destroyed a Wyoming Chinese community.[49] In Washington Territory, Yellow Peril fear provoked the Attack on Squak Valley Chinese laborers, 1885; the arson of the Seattle Chinatown; and the Tacoma riot of 1885, by which the local white inhabitants expelled the Chinese community from their towns.[49] In Seattle, the Knights of Labor expelled 200 Chinese people with the Seattle riot of 1886. In Oregon, 34 Chinese gold miners were ambushed, robbed, and killed in the Hells Canyon Massacre (1887). Moreover, concerning the experience of being Chinese in the 19th-century U.S., in the essay "A Chinese View of the Statue of Liberty" (1885), Sauum Song Bo said:

Seeing that the heading is an appeal to American citizens, to their love of country and liberty, I feel my countrymen, and myself, are honored in being thus appealed to, as citizens in the cause of liberty. But the word liberty makes me think of the fact that this country is a land of liberty for men of all nations, except the Chinese. I consider it an insult to us Chinese to call on us to contribute towards building, in this land, a pedestal for a statue of liberty. That statue represents Liberty holding a torch, which lights the passage of those of all nations who come into this country. But are Chinese allowed to come? As for the Chinese who are here, are they allowed to enjoy liberty as men of all other nationalities enjoy it? Are they allowed to go about everywhere free from insults, abuse, assaults, wrongs and injuries from which men of other nationalities are free?[50]

20th century

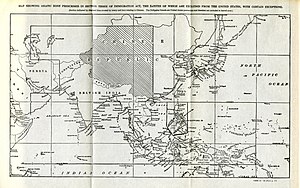

Under nativist political pressure, the Immigration Act of 1917 established an Asian Barred Zone of countries from which immigration to the U.S. was forbidden. The Cable Act of 1922 (Married Women's Independent Nationality Act) guaranteed citizenship to independent women unless they were married to a non-white alien ineligible for naturalization.[51] During the 1920s, when the Cable Act was law, Asian men and women were excluded from American citizenship.[52][53]

In practice, the Cable Act of 1922 reversed some racial exclusions, and granted independent-woman citizenship exclusively to women married to white men. Analogously, the Cable Act allowed the U.S. government to revoke the citizenship of an American white woman married an Asian man. Nonetheless, legalized Yellow Peril racism was formally challenged before the U.S. Supreme Court, with the case of Takao Ozawa v. United States (1922), whereby a Japanese–American man tried to demonstrate that the Japanese people are a white race eligible for naturalized American citizenship, but the Court ruled that the Japanese are not white people; two years later, the National Origins Quota of 1924 specifically excluded the Japanese from the U.S.A. and from American citizenship.

Ethnic national character

To "preserve the ideal of American homogeneity", the Emergency Quota Act of 1921 (numeric limits) and the Immigration Act of 1924 (fewer southern and eastern Europeans) restricted admission to the United States according to the skin color and the race of the immigrant.[54] In practice, the Emergency Quota Act used outdated census data to determine the number of colored immigrants to admit to the U.S. To protect WASP ethnic supremacy (social, economic, political) in the 20th century, the Immigration Act of 1924 used the twenty-year-old census of 1890, because its 19th-century demographic-group percentages favored more admissions of WASP immigrants from western and northern Europe, and fewer admissions of colored immigrants from Asia and southern and eastern Europe.[55]

To ensure that the immigration of colored peoples did not change the WASP national character of the United States, the National Origins Formula (1921–1965) meant to maintain the status quo percentages of "ethnic populations" in lesser proportion to the existing white populations; thus, the yearly quota allowed only 150,000 colored people into the U.S.A. In the event, the national-origins Formula was voided and repealed with the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965.[56]

Eugenic apocalypse

Eugenicists used the Yellow Peril to misrepresent the U.S. as an exclusively WASP nation threatened by miscegenation with the Asian Other; they expressed their racism with biological language (infection, disease, decay) and imagery of penetration (wounds and sores) of the white body.[57]: 237–238 In The Yellow Peril; or, Orient vs. Occident (1911), the end time evangelist G. G. Rupert said that Russia would unite the colored races to facilitate the Oriental invasion, conquest, and subjugation of the West; said white supremacy is in the Christian eschatology of verse 16:12 in the Book of Revelation: "Then the sixth angel poured out his bowl on the great Euphrates River, and it dried up so that the kings from the east could march their armies toward the west without hindrance".[58] As an Old-Testament Christian, Rupert believed the racialist doctrine of British Israelism, and said that the Yellow Peril from China, India, Japan, and Korea, were attacking Britain and the U.S.A., but that Jesus would halt the Asian conquest of the Western world.[59]

In The Rising Tide of Color Against White World-Supremacy (1920), the eugenicist Lothrop Stoddard said that either China or Japan would unite the colored peoples of Asia and lead them to destroy white supremacy in the Western world, and that the Asian conquest of the world began with the Japanese victory in the Russo–Japanese War (1905). As a white supremacist, Stoddard presented his racism with Biblical language and catastrophic imagery depicting a rising tide of colored people meaning to invade, conquer, and subjugate the white race.[60]

Political opposition

In that cultural vein, the phrase "yellow peril" was common editorial usage in the newspapers of publisher William Randolph Hearst.[61] In the 1930s, Hearst's newspapers realized a campaign of vilification (personal and political) against Elaine Black, an American Communist and political activist, whom he denounced as a libertine "Tiger Woman" for her interracial cohabitation with the Asian man Karl Yoneda, who also was a Communist.[62] In 1931, interracial marriage was illegal in California, but, in 1935, Black and Yoneda married in Seattle, Washington, a city and a state were interracial marriage was legal.[62]

Socially acceptable Asian

In the 1930s, Yellow Peril stereotypes were common to US culture, exemplified by the cinematic versions of the Asian detectives Charlie Chan (Warner Oland) and Mr. Moto (Peter Lorre), originally literary detectives in novels and comic strips. White actors portrayed the Asian men and made the fictional characters socially acceptable in mainstream American cinema, especially when the villains were secret agents of Imperial Japan.[63]: 159

American proponents of the Japanese Yellow Peril were the military-industrial interests of the China Lobby (right-wing intellectuals, businessmen, Christian missionaries) who advocated financing and supporting the warlord Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, a Methodist convert whom they represented as the Christian-Chinese saviour of China, then amidst the Chinese Civil War (1927–1937, 1946–1950). After the Japanese invaded China in 1937, the China Lobby successfully pressured the U.S. government to aid Chiang Kai-shek's faction. The news media's reportage (print, radio, cinema) of the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–45) favored China, which politically facilitated the American financing and equipping of the anti-communist Kuomintang, the Chiang Kai-shek faction in the civil war against the Communist faction led by Mao Tse-tung.[63]: 159

Pragmatic racialism

In 1941, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the Roosevelt administration formally declared China an ally of the U.S., and the news media modified their use of Yellow Peril ideology to include China to the West, criticizing contemporary anti-Chinese laws as counterproductive to the war effort against Imperial Japan.[63]: 165–166 The wartime zeitgeist and the geopolitics of the U.S. government presumed that defeat of the Imperial Japan would be followed by postwar China developing into a capitalist economy under the strongman leadership of the Christian Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek and the Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party).

In his relations with the American government and his China Lobby sponsors, Chiang requested the repeal of American anti-Chinese laws; to achieve the repeals, Chiang threatened to exclude the American business community from the "China Market", the economic fantasy that the China Lobby promised to the American business community.[63]: 171–172 In 1943, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was repealed, but, because the National Origins Act of 1924 was contemporary law, the repeal was a symbolic gesture of American solidarity with the people of China.

Science fiction writer William F. Wu said that American adventure, crime, and detective pulp magazines in the 1930s had many Yellow Peril characters, loosely based on Fu Manchu; although "most [Yellow Peril characters] were of Chinese descent", the geopolitics of the time led white people to see Japan as a threat to the United States. In The Yellow Peril: Chinese Americans in American fiction, 1850–1940 (1982), Wu said that fear of Asians dates from the European Middle Ages, from the 13th-century Mongol invasion of Europe. Most Europeans had never seen an Asian man or woman, and the great differences in language, custom, and physique accounted for European paranoia about the non-white peoples from the Eastern world.[64]

21st Century American revival

The American academic Frank H. Wu said that anti-Chinese sentiment incited by politicians, such as Steve Bannon and Peter Thiel, is ushering a "new Yellow Peril" that is common to populist American politics that do not distinguish between foreigners and citizens.[65] That American cultural anxiety about the geopolitical ascent of the Peoples Republic of China originates in the fact that, for the first time in centuries, the Western world, led by the U.S., is challenged by a people whom Westerners viewed as culturally backward and racially inferior only a generation earlier.[66] That the U.S. perceives China as "the enemy", because their economic success voids the myth of white supremacy upon which the West claims cultural superiority over the East.[67] Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has facilitated and increased the occurrence of xenophobia and anti-Chinese racism, which the academic Chantal Chung said has "deep roots in yellow peril ideology". [68]

Australia

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, fear of the Yellow Peril was a cultural feature of the white peoples who sought to establish a country and a society in the Australian continent. The racialist fear of the non-white Asian Other was a thematic preoccupation common to invasion literature novels, such as The Yellow Wave: A Romance of the Asiatic Invasion of Australia (1895), The Coloured Conquest (1904), The Awakening to China (1909), and the Fools' Harvest (1939). Such fantasy literature featured an Asian invasion of "the empty north" of Australia, which was populated by the Aboriginal Australians, the non-white, native Other with whom the white emigrants competed for living space.[69] In the novel White or Yellow?: A Story of the Race War of A.D. 1908 (1887), the journalist and labour leader William Lane said that a horde of Chinese people legally arrived to Australia and overran white society and monopolized the industries for exploiting the natural resources of the Australian "empty north".[69]

White nation

As Australian invasion literature, White or Yellow? reflects Lane's nationalist racialism and left-wing politics in a future history of Australia under attack by the Yellow Peril. In the near future, British capitalists manipulate the Australian legal system and successfully arrange the mass immigration of Chinese workers to Australia, regardless of the socio-economic consequences to Australian common folk and their society. The economic, cultural, and sexual conflicts that resulted from the British manipulation of the local economy provoke a White vs. Yellow race war throughout Australia. The racialist representations of Yellow Peril ideology in the narrative of White or Yellow? justify white Australians' killing the Chinese workers as an existential response for physical and economic control of Australia.[42]: 26–27 Moreover, the leaders of the labour and trade unions greatly opposed the immigration of low-wage Chinese workers, whom they portrayed as an economic threat to Australia; and whose libertinism threatens White Christian civilisation, which thematically addresses the psychosexual threat of miscegenation (mixing of the races), which is an apolitical call to racial unity among white Australians.[42]: 24

Culturally, the invasion novels about the Yellow Peril threat expressed the white man's sexual fear of voracious Asian sexuality, with scenes of white women in sexual peril, usually rape and seduction aided by the sensual and moral release of opium.[69] A white woman who was raped or seduced by a Chinese man had suffered "a fate worse than death"; thus defiled, the white woman forever is a sexual untouchable to other white men.[69] In that moralistic vein, in the 1890s, labour activist and feminist Rose Summerfield voiced the white female sexual fear of the Yellow Peril by warning society of the unnatural lust in the eyes of Chinese men when they looked upon the pulchritude of the white women of Australia.[42]: 24

Racial equality thwarted

In 1901, the Australian federal government adopted the White Australia policy that had been informally initiated with the Immigration Restriction Act 1901, which generally excluded Asians, but especially excluded the Chinese and the Melanesian peoples. Historian C. E. W. Bean said that the White Australia policy was "a vehement effort to maintain a high, Western standard of economy, society, and culture (necessitating, at that stage, however it might be camouflaged, the rigid exclusion of Oriental peoples)" from Australia.[71] In 1913, appealing to the irrational fear of the Yellow Peril, the film Australia Calls (1913) depicted a "Mongolian" invasion of Australia, which eventually is defeated by ordinary Australians with underground, political resistance and guerrilla warfare, and not by the army of the Australian federal government.[72]

In 1919, at the Paris Peace Conference (28 June 1919), supported by Britain and the U.S., Australian Prime Minister Billy Hughes vehemently opposed Imperial Japan's request for the inclusion of the Racial Equality Proposal to Article 21 of the Covenant of the League of Nations (13 February 1919):

The equality of nations being a basic principle of the League of Nations, the High Contracting Parties agree to accord, as soon as possible, to all alien nationals of states, members of the League, equal and just treatment in every respect, making no distinction, either in law or in fact, on account of their race or nationality.[73]

Aware that Britain opposed Japanese racial equality by way of the clause in Article 21 of the Covenant, conference chairman U.S. President Woodrow Wilson acted to prevent de jure racial equality among the nations of the world, with his unilateral requirement of a unanimous vote by the countries in the League of Nations. On 11 April 1919, most countries in the conference voted to include the Racial Equality Proposal to Article 21 of the Covenant of the League of Nations; only Britain and the U.S. opposed legislated racial equality. Moreover, to maintain the White Australia policy, the Australian government sided with Britain and voted against Japan's formal request that the Racial Equality Proposal be included to Article 21 of the covenant of the League of Nations; that defeat in international relations greatly influenced Imperial Japan to confront the Western world.[74]

France

Colonial empire

In 1890s France, the Péril jaune (Yellow Peril) was invoked in negative comparisons of the low French birth rate of the French and the high Asian birth rate.[75] Accordingly, there was the cultural fear that one day Asians would "flood" France, which could be successfully countered only by increased fecundity of French women. Then, France would possess enough soldiers to thwart the eventual flood of immigrants from Asia.[75] From that racialist perspective, the French press sided with Imperial Russia during the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905) and represented the Russians as heroically defending the white race against the Japanese Yellow Peril.[76]

In 1904, the French journalist René Pinon reported the cultural, geopolitical and existential threat that the Yellow Peril posed to white, Western civilization:

The "Yellow Peril" has entered already into the imagination of the people, just as represented in the famous drawing [Peoples of Europe, Guard Your Most Sacred Possessions,1895] of the Emperor Wilhelm II: In a setting of conflagration and carnage, Japanese and Chinese hordes spread out over all Europe, crushing under their feet the ruins of our capital cities and destroying our civilizations, grown anemic due to the enjoyment of luxuries, and corrupted by the vanity of spirit.

Hence, little by little, there emerges the idea that even if a day must come (and that day does not seem near) the European peoples will cease to be their own enemies and even economic rivals, there will be a struggle ahead to face and there will rise a new peril, the yellow man.

The civilized world has always organized itself before and against a common adversary: for the Roman world, it was the barbarian; for the Christian world, it was Islam; for the world of tomorrow, it may well be the yellow man. And so we have the reappearance of this necessary concept, without which peoples do not know themselves, just as the "Me" only takes conscience of itself in opposition to the "non-Me": The Enemy.[25]: 124

Despite the Christian idealism of the civilizing mission, from the start of colonization in 1858, the French exploited the land of Vietnam as inexhaustible and the Vietnamese people as beasts of burden.[77]: 67–68 During the First Indochina War (1946–1954), the French justified their colonial return of Vietnam as defense of the white West against the péril jaune – specifically the Communist Party of Vietnam, as puppets of Red China in the communist conspiracy to conquer the world.[78] Hence, French orientalism defined the Asian Other as less than human, combined with anticommunism, which dehumanization allowed atrocities against Viet Minh prisoners of war, during la sale guerre("dirty war") against international communism.[77]: 74 The Yellow Peril metaphors in French anti-communist media portrayed the Viet Minh as part of the innombrables masses jaunes (innumerable yellow hordes) and one of many vagues hurlantes (roaring waves) of masses fanatisées (fanatical hordes).[79]

Contemporary France

In Behind the Bamboo Hedge: The Impact of Homeland Politics in the Parisian Vietnamese Community (1991), Gisèle Luce Bousquet, said that the péril jaune, which traditionally colored French perceptions of Asians, especially that of the Vietnamese, remains a cultural prejudice of contemporary France.[80] Hence, the Vietnamese people in France are perceived and resented as academic overachievers who take jobs from "native French" people.[80]

In 2015, the front cover of the January issue of Fluide Glacial magazine featured a cartoon, Yellow Peril: Is it Already Too Late?, which depicts a Chinese-occupied Paris where a sad Frenchman pulling a rickshaw, with a Chinese passenger (dressed as a 19th c. French colonial official) accompanied by a barely dressed, blond French woman.[81][82] The editor of Fluide Glacial, Yan Lindingre defended the cover and the subject as satire and mockery of French fears of China's economic threat to France.[82] In an editorial directed to the complaining Chinese, Lindingre said, "I have just ordered an extra billion copies printed, and will send them to you via a chartered flight. This will help us balance our trade deficit and give you a good laugh".[82]

Italy

In the 20th century, from their perspective, as nonwhite nations in a world order dominated by the white nations, the geopolitics of Ethiopia–Japan relations allowed Imperial Japan and Ethiopia to avoid imperialist European colonization of their countries and nations. Before the Second Italo-Ethiopian War (1934–1936), Imperial Japan had given diplomatic and military support to Ethiopia against invasion by the Fascist Italy, which implied military assistance. In response to that Asian anti-imperialism, Benito Mussolini ordered a Yellow Peril propaganda campaign by the Italian press, which represented Imperial Japan as the military, cultural, and existential threat to the Western world, by way of the dangerous "yellow race–black race" alliance meant to unite Asians and Africans against the white people of the world.[83]

In 1935, Mussolini warned of the Japanese Yellow Peril, specifically the racial threat of Asia and Africa uniting against Europe.[83] In the summer of 1935, the National Fascist Party (1922–43) often staged anti–Japanese political protests throughout Italy.[84] Nonetheless, as right-wing imperial powers, Japan and Italy pragmatically agreed to disagree; in exchange for Italian diplomatic recognition of Manchukuo (1932–45), the Japanese puppet state in China, Imperial Japan would not aid Ethiopia against Italian invasion and so Italy would end the anti–Japanese Yellow Peril propaganda in the national press of Italy.[84]

Mexico

During the Mexican Revolution (1910–20), Chinese-Mexicans were subjected to racist abuse, like before the revolt, for not being Christians, specifically Roman Catholic, for not being racially Mexican, and for not soldiering and fighting in the Revolution against the thirty-five-year dictatorship (1876–1911) of General Porfirio Díaz.[85]: 44

The notable atrocity against the Yellow Peril was the three-day Torreón massacre (13–15 May 1911) in northern Mexico, wherein the military forces of Francisco I. Madero killed 308 Asian people (303 Chinese, 5 Japanese), because they were deemed a cultural threat to the Mexican way of life. The massacre of Chinese- and Japanese-Mexicans at the city of Torreón, Coahulia State, was not the only such atrocity perpetrated in the Revolution. Elsewhere, in 1913, after the Constitutional Army captured the city of Tamasopo, San Luis Potosí state, the soldiers and the town-folk expelled the Yellow Peril from town by sacking and burning the Chinatown.[85]: 44

During and after the Mexican Revolution, the Roman Catholic prejudices of Yellow Peril ideology facilitated racial discrimination and violence against Chinese Mexicans, usually for "stealing jobs" from native Mexicans, etc. Anti–Chinese, nativist propaganda misrepresented the Chinese people as unhygienic, prone to immorality (miscegenation, gambling, opium-smoking) and spreading diseases that would biologically corrupt and degenerate La Raza (the Mexican race) and generally undermining the Mexican patriarchy.[86]

Moreover, from the racialist perspective, besides stealing work from Mexican men, Chinese men were stealing Mexican women from the native Mexican men who were away fighting the Revolution, overthrowing and expelling the dictator Porfirio Díaz and his foreign sponsors from Mexico.[87] In the 1930s, approximately 70% of the Chinese and the Chinese–Mexican population was expelled from the Mexican United States by the bureaucratic ethnic culling of the Mexican population.[88]

Ottoman Empire

In 1908, after the Young Turk Revolution, the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) achieved political dominance, reinforced, five years later, after the Raid on the Sublime Porte in 1913. The CuP greatly admired the Japanese for modernizing their country while retaining its "Eastern spiritual essence", and it proclaimed its intention to transform the Ottoman Empire into the "Japan of the Near East".[89]

In an inversion of the Yellow Peril racism of the Western world, the Young Turks thought of entering an alliance with Imperial Japan that would unite all the peoples of "the East" to wage a war of extermination against the much-hated Western nations whose empires dominated the world.[90]: 54–55 Culturally, for the Young Turks, the term "yellow" of the "Eastern gold" color symbolized the innate moral superiority of the Eastern world over the corrupt, materialistic West.[90]: 53–54

South Africa

From 1904 to 1910, the Unionist Government of the Britain authorized the immigration to South Africa of approximately 63,000 Chinese laborers to work the gold mines in the Witwatersrand basin after the conclusion of the Second Boer War. After 1910, most Chinese miners were repatriated to China because of the great opposition to them, as "colored people", in the white society of South Africa, analogous to antiChinese laws in the US during the early 20th century.[91][92]

The mass immigration of indentured Chinese laborers to mine South African gold for wages lower than acceptable to the native white men, contributed to the electoral loss of the financially conservative British Unionist government that then governed South Africa.[93]: 103

On 26 March 1904, approximately 80,000 people attended a social protest against the use of Chinese labourers in the Transvaal held in Hyde Park, London, to publicize the exploitation of Chinese South Africans.[93]: 107 The Parliamentary Committee of the Trade Union Congress then passed a resolution declaring:

That this meeting, consisting of all classes of citizens of London, emphatically protests against the action of the Government in granting permission to import into South Africa indentured Chinese labour under conditions of slavery, and calls upon them to protect this new colony from the greed of capitalists and the Empire from degradation.[94]

In the event, despite the racial violence between white South African miners and Chinese miners, the Unionist government achieved the economic recovery of South Africa after the Anglo–Boer War by rendering the gold mines of the Witwatersrand Basin the most productive in the world.[93]: 103

Turkey

There have historically been very strong antiChinese feelings in Turkey owing to allegations of human rights abuses against the Muslim Turkic Uighurs in China's Xinjiang province.[95] At one anti-Chinese demonstration in Istanbul, a South Korean tourist was threatened with violence even she protested that "I am not Chinese, I am Korean".[95] In response, Devlet Bahçeli, leader of the extreme right-wing Nationalist Movement Party stated: "How does one distinguish between Chinese and Koreans? Both have slanted eyes".[95]

However, these negative sentiments have decreased in recent years. According to a November 2018 INR poll, 46% of Turks view China favorably, up from less than 20% in 2015. A further 62% thought that it is important to have strong trade relationship with China.[96]

New Zealand

In the late 19th and the early 20th centuries, populist Prime Minister Richard Seddon compared the Chinese people to monkeys, and so used the Yellow Peril to promote racialist politics in New Zealand. In 1879, in his first political speech, Seddon said that New Zealand did not wish her shores "deluged with Asiatic Tartars. I would sooner address white men than these Chinese. You can't talk to them, you can't reason with them. All you can get from them is 'No savvy'".[97]

Moreover, in 1905, in the city of Wellington, the white supremacist Lionel Terry murdered Joe Kum Yung, an old Chinese man, in protest against Asian immigration to New Zealand. Laws promulgated to limit Chinese immigration included a heavy poll tax, introduced in 1881 and lowered in 1937, after Imperial Japan's invasion and occupation of China. In 1944, the poll tax was abolished, and the New Zealand government formally apologized to the Chinese populace of New Zealand.[98]

Sexual fears

This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (June 2020) |

This section is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (June 2020) |

Background

The core of Yellow Peril ideology is the white man's fear of Oriental sexual voracity of the Seductress (the Dragon Lady and the Lotus Blossom varieties) and of the Seducer who possess an unnatural and perverse sex appeal, which is a moral and a mortal threat to the white civilization of the Christian West.[7]: 3 Racist revulsion towards miscegenation — interracial sexual intercourse — communicated with sexual stereotypes of the Yellow Peril, derives from the fear of mixed-race children, whose existence threatens Whiteness proper.[63]: 159 Within the term 'oriental' there are many contradictory sexual associations based on nationality. A man could be seen as Japanese and somewhat kinky, or Filipino and 'available'. The very same man could be seen as 'Oriental' and therefore sexless and perverse.[99]

The seducer

The seductive Asian man (wealthy and cultured) was the more common form of white-male fear of the Asian sexual "other." In the Asian seducer, the sexual threat of the Yellow Peril was realized with successful sexual competition – seduction or rape – which irredeemably corrupted the white woman, beyond redemption. (see: 55 Days at Peking, 1963)[7]: 3 In Romance and the "Yellow Peril": Race, Sex, and Discursive Strategies in Hollywood Fiction (1994) the critic Gary Hoppenstand identified interracial sexual-intercourse as a threat to the culture of whiteness:

The threat of rape, the rape of white society dominated the yellow formula. The British or American hero, during the course of his battle against the yellow peril, overcomes numerous traps and obstacles in order to save his civilization, and the primary symbol of that civilization: white women. Stories featuring the Yellow Peril were arguments for white purity. Certainly, the potential union of the Oriental and white implied at best, a form of beastly sodomy, and at worse, a Satanic marriage. The Yellow Peril stereotype easily became incorporated into Christian mythology, and the Oriental assumed the role of the devil or demon. The Oriental rape of white woman signified a spiritual damnation for the women, and at the larger level, white society.[7]: 3

In The Cheat (1915), the wealthy Hishuru Tori (Sessue Hayakawa) is a Japanese sexual predator and sadist whose attentions menace Edith Hardy (Fannie Ward), an American housewife.[7]: 19–23 Although superficially Westernized, Tori is a rapist, which reflects his true cultural identity as an Asian man.[7]: 16–17 In being "brutal and cultivated, wealthy and base, cultured and barbaric, Tori embodies the contradictory qualities Americans associate with Japan".[7]: 19 Initially, the story presents Tori as an "asexual" man associating with the high society of Long Island; yet, once Edith is in his private study, decorated with Japanese art, he is a man of "brooding, implicitly sadistic sexuality".[7]: 21 At times, before Tori attempts to rape Edith, the narrative of the story implies that she is attracted to him and corresponds his sexual interest in her. To assure commercial success, the cast of The Cheat (1915) featured the Japanese actor Sessue Hayakawa – who was a male sex symbol in the cinema of that time – which was a cultural fact that resonated on-screen and off-screen as a sexual threat to the existing racial hierarchy and sexual mores of white men in 1915.[7]: 21–22 & 25.

In Shanghai Express (1932), General Henry Chang (Warner Oland) is a warlord of Eurasian origin (Chinese and American), whom the narrative presents as an asexual man, which excludes him from the realm of Western sexual mores and the racialist order; thus, he is dangerous to the Westerners he holds hostage.[7]: 64 Though Chang is Eurasian, he is prouder of his Chinese heritage, and rejects his American heritage, which rejection confirms his Oriental identity.[7]: 64

In 1931, the Chinese Civil War has rendered the country into a version of Hell, which a diverse group of Westerners must traverse by train, from Beijing to Shanghai, a voyage that turns for the worse when General Chang's soldiers hijack the train.[7]: 61 The story implies that Gen. Chang is a bisexual man who desires to rape both the heroine, Shanghai Lily (Marlene Dietrich), and the hero, Captain Donald "Doc" Harvey (Clive Brook).[7]: 64

Moreover, when the German opium smuggler Erich Baum (Gustav von Seyffertitz) insults Chang, the warlord symbolically rapes him by branding; the sadistic Chang derives sexual pleasure in branding Baum with a red-hot poker.[7]: 64–65 After being branded, the once proud Baum becomes notably cowed and submissive to Chang, then owns him in realization of the ultimate fear of the Yellow Peril: Westerners enslaved to the unnatural and perverse sexuality of the East; later, Chang rapes Hui Fei (Anna May Wong).[7]: 65

Gen. Chang's desire to blind Capt. Harvey also is a castration metaphor, a taboo subject even for the intellectually permissive Production code in effect in 1932.[7]: 65 In marked contrast to Chang's bisexuality and his "almost effeminate polish", the British Army Captain Harvey is a resolutely heterosexual man, a tough, rugged soldier tested and proved in the trenches of the First World War (1914–18); the Briton is a model of Western masculinity and strength.[7]: 64–65 Throughout, the narrative implies that Shanghai Lily and Hui Fei are in a lesbian relationship, thus, at story's end, Lily's choice of Capt. Harvey as her lover, reaffirms the heterosexual appeal of the Western man and redeems her from prostitution.[7]: 60–65

The narrative of Shanghai Express embraces the stereotypes of the Yellow Peril through the Eurasian character of Gen. Chang, and also undermines their inhumanity through the suffering of Hui Fei, who cries inconsolably after Chang raped her, such humanity allows the audience to sympathize with a nonwhite Other.[7]: 65 As a courtesan, Hui Fei is condescended to by every Western character, except her best friend Lily, because of her race and profession, but is shown as dignified woman who stands up for herself.[100]: 232–234 At the climax, Hui Fei kills Gen. Chang to save Harvey from being blinded by him; she explains that killing Chang regained the self-respect he had taken from her. Throughout, the narrative has suggested that Shanghai Lily and Hui Fei are more attracted to each other than to Capt. Harvey. That detail of character, which suggests that Hui Fei is sexually abnormal, was socially daring drama in 1932, because Western mores considered bisexuality to be unnatural.[100]: 232, 236 The same criticism of sexual orientation might apply to Lily, but the story concludes with resumed heterosexuality, when she kisses Capt. Harvey, while Hui Fei walks away alone, sad for having been raped and for losing her best friend to Capt. Harvey.[100]: 232, 236–237

The seductress

The Dragon Lady is a cultural representation of white fear of Asian female sexuality. The Asian seductress is a charming, beautiful, and sexually insatiable woman who readily and easily dominates men. As a sexual Other, the dragon-lady woman is a tempting, but morally degrading object of desire for the white man.[7]: 3

In Western cinema genre, the cowboy town features an Asian woman who usually portrayed as a scheming prostitute, always seeking to use her sexuality (charisma and physical sex-appeal) to beguile and dominate the white man.[101] In the American television program Ally McBeal (1997–2002), the Dragon Lady stereotype was personified in the Ling Woo character, a domineering woman whose Chinese ethnicity includes sexual abilities that no white woman could hope to match.[102]

In the late 20th century, such a sexual representation of the Yellow Peril, introduced in the comic strip Terry and the Pirates (27 September 1936), indicates that the Western imagination continues to associate Asia, as a region of exotic beauty and material opulence, of moral laxity and sensual excess, and of cultural decadence. To the Westerner, the seductiveness of the Orient implies spiritual threat and hidden existential danger, derived from the desire to be enticed and hypnotized, to be entrapped and suffocated in a masochistic surrender of white identity, "to be engulfed by what Freudians might describe as a metaphoric womb–tomb".[7]: 67–68

The Lotus Blossom

A variant Yellow Peril seductress is presented in the white savior romance between a "White Knight" from the West and a "Lotus Blossom" from the East; each redeems the other by way of mutual romantic love. Despite being a threat to the passive sexuality of white women, the romantic narrative favorably portrays the Lotus Blossom character as a woman who needs the love of a white man to rescue her from objectification by a flawed Asian culture.[7]: 108–111 As a heroine, the Lotus-Blossom-woman is an ultra-feminine model of Asian pulchritude, social grace, and culture, whose own people trapped her in an inferior, gender-determined social-class. Only a white man can rescue her from such a cultural impasse, thereby, the narrative reaffirms the moral superiority of the Western world.[7]: 108–111

- Hong Kong

In The World of Suzie Wong (1960), the eponymous anti-heroine is a lost-soul prostitute saved by the love of Robert Lomax (William Holden), an American painter living in Hong Kong.[7]: 123 The East–West sexual differences available to Lomax are two: an unpleasant, career-minded British girlfriend, Kay O'Neill (Sylvia Syms), who is mannishly independent; and Suzie Wong (Nancy Kwan), who is a conventionally feminine and submissive woman. She works as a sexual prostitute because of her poverty in Hong Kong.[7]: 113–116

Moreover, in 1959, the economic ascendancy of Hong Kong, as part of the "Asian Tiger Economy", had just begun to improve life for the Chinese. Nonetheless, despite the film's historical inaccuracy of background, the cultural contrast of the representations of Suzie Wong and Kay O'Neill imply that if a Western woman wants to win a cultured, Western man (like the painter Robert Lomax) she should emulate the sexually passive prostitute (Suzie Wong) rather than the independent and "controlling" career-woman (Kay O'Neill).[7]: 116 As an Oriental stereotype, the submissive Asian girl (Lotus -Blossom Wong) shows her innate masochism when she "proudly displays signs of a beating, to her fellow hookers, and uses it as evidence that her man loves her", which condition further increases Lomax's need to rescue her.[103]

Psychologically, the painter Lomax needs the prostitute Wong, as the muse whose eroticism inspires the self-discipline necessary for becoming an accomplished painter.[7]: 120 Suzie Wong is an illiterate orphan who was sexually abused as a girl; thus her toleration of abuse by most of her Chinese clients.[7]: 113 That Lomax is portrayed as more enlightened and caring, than Chinese and British men, implies the moral superiority of the American culture over the decadent society of Hong Kong and over the decayed British Empire; the Americans shall be better geopolitical and cultural custodians of Asia than were the British.[7]: 115 When a British sailor attempts to rape Wong, the chivalrous Lomax rescues her and beats the would-be rapist; all the while, Chinese men sat by, indifferent to the rape of a prostitute.[7]: 115

As a Lotus Blossom stereotype of the Yellow Peril, the prostitute Suzie Wong is a single mother abandoned by her Chinese lover; the socially dramatic backstory of the woman emphasizes the casual cruelty of Hong Kong's Asian society.[7]: 117 In contrast to the casual brutality (emotional and physical) with which Chinese and British characters treat Wong, the sensitive artist Lomax loves her as a "child–woman", and saves her with a new social identity as his Lotus Blossom, an ideal woman who is docile under his paternalism.[7]: 120–123 Yet Lomax's love is conditional; throughout the story, she wears a Chinese Cheongsam dress, but when she dresses in Western clothes, Lomax rips off her dress, and orders her to only wear a cheongsam – Suzie Wong is acceptable only as an Asian girl created in conformity to the Western cultural mores of proper womanhood and femininity.[7]: 121

- Vietnam

In the musical Miss Saigon (1989), the country of Vietnam is represented as a beautifully exotic and mysterious place of sensuous beauty, incomprehensible savagery, and great filth.[104]: 34 The opening chorus of the first song, "The Heat's on Saigon", begins thus: "The heat's on Saigon / The girls are hotter 'n hell / Tonight one of these slits will be Miss Saigon / God, the tension is high / Not to mention the smell".[104]: 34

The first act, set in Saigon City, presents the adolescent prostitute-heroine named Kim, who is portrayed as a demure "Lotus Blossom" who is a sexually available and submissive Asian woman whose life is defined by her love for a white man, the American Marine Chris Scott.[104]: 28–32 That every Vietnamese woman is a prostitute, and that all, but one, are Dragon Ladies who easily display their bodies in bikini swim suits, confirms the Western stereotype of the hyper-sexual Asian woman.[104]: 31–32 The second act, set in Thailand, portrays Thai women as prostitutes, and reinforces the Western stereotype of the hyper-sexual Asian woman who is perpetually available to copulate. At the Dreamland brothel, Kim is the only woman who does not always dress in a bikini swimsuit.[104]: 32 Her passivity, moral purity, and fidelity to the Marine Chris, who abandoned her and their son in South Vietnam, returned to the U.S. and married the American woman Ellen, suggests that subservience is the proper relation between an Asian woman and a white man.[104]: 29

Despite working as a prostitute, the seventeen-year-old Kim is a virginal innocent who needs the Marine Chris to protect her from the cruel world of Saigon City.[104]: 32 One of the songs that Chris sings about her suggests that Kim is Vietnam.[104]: 31 In contrast to the aggressive Vietnamese male characters, the passive Kim is portrayed as being the true Vietnam.[104]: 31–33 Moreover, the man Thuy, a Viet Cong guerrilla who wants to marry Kim, is portrayed as a jealous and possessive, violent and cruel man who seeks to exploit her, the opposite of Chris, who only seeks to love her.[104]: 34 The character of the pimp, Tran Van Dinh, aka "The Engineer", is a Eurasian man whose sexuality is "simply incomprehensible, illegible, indeterminate, even as it is spectacularly displayed".[104]: 41

East Asia studies Professor Karen Shimakawa described the Engineer as "simultaneously lascivious, sexually exploitative, pansexual and desexualized."[104]: 41 Although the character was born of a French father and a Vietnamese mother, the libretto always emphasizes his Oriental-ness.[104]: 39 "The Engineer embodies an un-categorizable, yet spectacular perversity – a condition that, the logic of the play suggests, is hereditary: it is the direct result of his racially and nationally mixed beginnings in prostitution and sexual debauchery".[104]: 41 The best friend of Chris is a black man named John, an enthusiastic patron of the Dreamland brothel who fulfills the racial stereotype of the sexually voracious black man.[104]: 30 Unlike the romantic Chris, John is given to crude, macho boasting about his sexual prowess, and only sees the women of the Dreamland brothel as sexual objects.[104]: 30–32 In contrast to the flawed masculinity of the colored men, the white Chris is a kind, gentle man who genuinely loves Kim, and sings: "I wanted to save her, protect her / Christ, I'm an American / How could I fail to do good?".[104]: 29

Fu Manchu and criminal kin

The Yellow Peril was a common subject for colonial adventure fiction, of which the representative villain is Dr. Fu Manchu, created by Sax Rohmer, and featured in thirteen novels (1913–59). Fu Manchu is an evil Chinese gangster and mad scientist who means to conquer the world, despite continually being foiled by the British policeman and gentleman spy Sir Denis Nayland Smith, and his assistant Dr. Petrie.