Timeline of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370

This article needs to be updated. (September 2018) |

| Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 |

|---|

The timeline of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 lists events associated with the disappearance of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370[a]—a scheduled, commercial flight operated by Malaysia Airlines from Kuala Lumpur International Airport to Beijing Capital International Airport on 8 March 2014 with 227 passengers and 12 crew. Air traffic control lost contact with Flight 370 less than an hour into the flight, after which it was tracked by military radar crossing the Malay Peninsula and was last located over the Andaman Sea. Analysis of automated communications between the aircraft and a satellite communications network has determined that the aircraft flew into the southern Indian Ocean, before communication ended shortly after 08:19 (UTC+8:00). The disappearance initiated a multi-national search effort that became the most expensive search in aviation history.[2][3][4][5]

In the weeks after Flight 370's disappearance, the search focused on waters in Southeast Asia and an investigation into the disappearance was opened. After a week of searching, Malaysia announced that analysis of communications between the aircraft and a satellite communications network had found that Flight 370 continued to fly for several hours after it lost contact with air traffic control. Its last communication on the network was made along one of two arcs stretching north-west into Central Asia and southwest into the southern Indian Ocean. The northern arc was discounted and the focus of the search shifted to a remote area of the southern Indian Ocean.

On 18 March, a surface search in the southern Indian Ocean, led by Australia, began; it continued until 28 April and searched 4,500,000 square kilometres (1,700,000 sq mi) of ocean.[6] On 24 March 2014, Malaysia's Prime Minister announced that Flight 370 ended in the southern Indian Ocean with no survivors. In early April, an effort to find the signals emitted from underwater locator beacons (ULBs) attached to the aircraft's flight recorders, which have a 30- to 40-day battery life, was made. Some possible ULB detections were made and a seafloor sonar survey in the vicinity of the detections to scan the seafloor was initiated. The seafloor sonar survey ended on 28 May and scanned 860 km2 (330 sq mi) of seafloor.[7] Neither the surface search nor the seafloor sonar survey found any objects related to Flight 370.

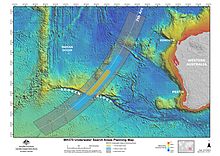

In May 2014, planning for the next phase of the search was initiated. A bathymetric survey was carried out to measure the seafloor topography in the areas where the next phase was conducted; the survey charted 208,000 km2 (80,000 sq mi) of seafloor topography and continued until December that year.[8] An underwater search began in October 2014 but failed to recover anything of value and was suspended in January 2017 after searching 120,000 km2 (46,000 sq mi) of the southern Indian Ocean.[9] On 29 July 2015, a flaperon from Flight 370 was discovered on a beach in Réunion, approximately 4,000 km (2,500 mi) west of the underwater search area; this location is consistent with drift from the underwater search area over the intervening 16 months.

Disappearance (8 March 2014)

Flight 370 took off from Kuala Lumpur International Airport at 00:42 local time (MYT; UTC+08:00) en route to Beijing Capital International Airport, where it was expected to arrive at 6:30 local time (CST; UTC+08:00). At 1:19, while Flight 370 was over the South China Sea between Malaysia and Vietnam, Malaysian air traffic control (ATC) instructed Flight 370 to contact the next ATC in Vietnam. The final voice contact from Flight 370 was made when its captain replied, "Good night. Malaysian Three Seven Zero". Two minutes later, the aircraft's transponder stopped functioning, causing it to disappear from ATC's secondary radar. Malaysian military radar continued to track the aircraft as it turned left, crossed the Malay Peninsula near the Malaysia–Thailand border, and travelled over the Andaman Sea.

At 2:22, the aircraft disappeared from Malaysian military radar, 200 nautical miles (370 km; 230 mi) north-west of Penang. At 2:25, the aircraft's satellite datalink, which was lost sometime between 01:07 and 02:03, was re-established. Thereafter, the aircraft's satellite data unit (SDU) replied to five hourly, automated status requests between 03:41 and 08:10, and two unanswered ground-to-aircraft telephone calls. At 08:19, the SDU sent a "log-on request" message to establish a satellite datalink, followed by the final transmission from Flight 370 eight seconds later. Investigators believe the 08:19 messages were made between the time of fuel exhaustion and the time the aircraft entered the ocean. After four hours of communication between several ATC centres, the Kuala Lumpur Aeronautical Rescue Coordination Centre was activated at 6:32. Malaysia Airlines released a press statement at 07:24, stating that contact with Flight 370 had been lost.

| Elapsed (HH:MM) | Time | Event | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MYT | UTC | ||

| 1:52 prior | 7 March | Captain Zaharie Ahmad Shah[10][11] signs in for duty.[12]: 1 | |

| 22:50 | 14:50 | ||

| 1:28 prior | 23:15 | 15:15 | First Officer Fariq Abdul Hamid[10][11] signs in for duty.[12]: 1 |

| 00:42 prior | 8 March | 16:00 | The aircraft's SDU logs onto the Inmarsat satellite communication network.[13]: 3 |

| 00:00 | |||

| 00:13 prior | 00:27 | 16:27 | ATC gives Flight 370 clearance to push back from the gate.[12]: 1 |

| 00:01:23 prior | 00:40:37 | 16:40:37 | ATC gives Flight 370 clearance to take off.[12]: 1 |

| 00:00 | 00:42 | 16:42 | Flight 370 takes off from runway 32R at Kuala Lumpur International Airport.[12]: 1 |

| 00:01 | 00:42:53 | 16:42:53 | ATC gives Flight 370 clearance to climb to Flight Level 180, approximately 18,000 ft (5,500 m)[b] and proceed directly to waypoint IGARI.[12]: 1 |

| 00:04 | 00:46:39 | 16:46:39 | Flight 370 is transferred from the airport's ATC to Lumpur Radar ATC.[12]: 2 Both the airport and Lumpur Radar ATC are based at the Kuala Lumpur Area Control Centre (KL ACC).[12]: 87–95 |

| 00:05 | 00:46:58 | 16:46:58 | ATC gives Flight 370 clearance to climb to Flight Level 250; approximately 25,000 feet (7,600 metres).[12]: 2 |

| 00:08 | 00:50:08 | 16:50:08 | ATC gives Flight 370 clearance to climb to Flight Level 350; approximately 35,000 feet (11,000 metres).[12]: 2 |

| 00:19 | 01:01:17 | 17:01:17 | The captain[c] informs ATC that Flight 370 has reached Flight Level 350.[12]: 2 |

| 00:25 | 01:07:48 | 17:07:48 | The final data transmission from Flight 370 using the ACARS protocol is made.[12]: 1 [13]: 36 |

| 00:25–01:22 | 01:07:48–02:03:41 | 17:07:48–18:03:41 | The satellite communication link is lost sometime during this period.[13]: 36 |

| 00:25 | 01:07:56 | 17:07:56 | The captain confirms that Flight 370 is flying at Flight Level 350.[12]: 2 |

| 00:37 | 01:19:30 | 17:19:30 | KL ACC instructs the crew to contact Ho Chi Minh ACC (HCM ACC). The aircraft passes waypoint IGARI as the captain replies, "Good night. Malaysian three seven zero." This is the final voice contact with Flight 370.[12]: 2 |

| 00:39 | 01:21:13 | 17:21:13 | The position symbol of Flight 370 disappears from KL ACC radar, indicating the aircraft's transponder is no longer functioning.[12]: 2 Malaysian military radar continues to track the aircraft, which "almost immediately"[12]: 3 begins a turn to the left until it is travelling in a south-westerly direction.[12]: 3 |

| 00:48 | 01:30 | 17:30 | Voice contact is attempted by another aircraft at the request of HCM ACC; mumbling and radio static are heard in reply.[14] |

| 00:55 | 01:37 | 17:37 | An expected half-hourly ACARS data transmission is not received.[15] |

| 00:56 | 01:39 | 17:38 | HCM ACC contacts KL ACC to inquire about Flight 370. HCM ACC says verbal contact was not established and Flight 370 disappeared from its radar screens near waypoint BITOD. KL ACC responds that Flight 370 did not return to its frequency after passing waypoint IGARI.[12]: 2 [16] |

| 01:04 | 01:46 | 17:46 | HCM ACC contacts KL ACC and informs them that radar contact with Flight 370 was established near IGARI but lost near BITOD and that verbal contact was never established.[16] |

| 01:10 | 01:52 | 17:52 | Flight 370 reached the southern end of Penang Island. First Officer Fariq Abdul Hamid's cellphone registered with a cell tower below, though no other data was transmitted. Flight 370 then turned towards northwest along the Strait of Malacca.[17] |

| 01:15 | 01:57 | 17:57 | HCM ACC informs KL ACC there was no contact with Flight 370, despite attempts on many frequencies and aircraft in the vicinity.[16] |

| 01:21 | 02:03:41 | 18:03:41 | Malaysia Airlines dispatch centre sends a message to the cockpit instructing pilots to contact Vietnam ATC, to which there is no response.[18] A ground-to-aircraft ACARS data request, transmitted from the ground station multiple times between 02:03–02:05, was not acknowledged by the aircraft's satellite data unit.[13]: 36–39 |

| 01:21 | 02:03:48 | 18:03:48 | KL ACC contacts HCM ACC and relays information from Malaysia Airlines' operations centre that Flight 370 is in Cambodian airspace.[16] |

| 01:33 | 02:15 | 18:15 | KL ACC queries Malaysia Airlines' operations centre, which replies that it is able to exchange signals with Flight 370, which is in Cambodian airspace.[16] |

| 01:36 | 02:18 | 18:18 | KL ACC contacts HCM ACC asking them whether Flight 370 was supposed to enter Cambodian airspace. HCM ACC replies that Flight 370's planned route did not take it into Cambodian airspace and that they had checked; Cambodia had no information about, or contact with, Flight 370.[16] |

| 01:40 | 02:22 | 18:22 | The last primary radar contact is made by the Malaysian military, 200 nautical miles (370 km; 230 mi) north-west of Penang, 6°49′38″N 97°43′15″E / 6.82722°N 97.72083°E[19]: 3 |

| 01:43 | 02:25 | 18:25 | A "log-on request" is sent by the aircraft on its satellite communication link to the Inmarsat satellite communications network. The link is re-established after being lost for between 22 and 68 minutes.[13]: 39 [19]: 18 This communication is sometimes erroneously referred to as the first hourly "handshake" after the flight's disappearing from radar.[20][21] |

| 01:52 | 02:34 | 18:34 | KL ACC queries Malaysia Airlines' operations centre about communication status with Flight 370, but it was not sure whether a message sent to Flight 370 was successful.[16] |

| 01:53 | 02:35 | 18:35 | Malaysia Airlines' operations centre informs KL ACC that Flight 370 is in a normal condition based on signals from the aircraft located at 14°54′00″N 109°15′00″E / 14.90000°N 109.25000°E (Northern Vietnam) at 18:33 UTC. KL ACC relays this information to HCM ACC.[16] |

| 01:57 | 02:39 | 18:39 | A ground-to-aircraft telephone call, via the aircraft's satellite link, goes unanswered.[13]: 40 [19]: 18 |

| 02:48 | 03:30 | 19:30 | Malaysia Airlines' operations centre informs KL ACC that position information was based on flight projection and is not reliable for aircraft tracking. Between 03:30 and 04:25, KL and HCM ACCs query Chinese air traffic control.[16] |

| 02:59 | 03:41 | 19:41 | Hourly, automated handshake between the aircraft and the Inmarsat satellite communication network.[13]: 40 |

| 03:59 | 04:41 | 20:41 | Hourly, automated handshake between the aircraft and the Inmarsat satellite communication network.[13]: 40 |

| 04:27 | 05:09 | 21:09 | Singapore ACC queried for information about Flight 370.[16] |

| 04:59 | 05:41 | 21:41 | Hourly, automated handshake between the aircraft and the Inmarsat satellite communication network.[13]: 40 |

| 05:48 | 06:30 | 22:30 | Flight 370 misses its scheduled arrival at Beijing Capital International Airport. |

| 05:50 | 06:32 | 22:32 | The Kuala Lumpur Aeronautical Rescue Coordination Centre (ARCC) is activated.[12]: 2 |

| 05:59 | 06:41 | 22:41 | Hourly, automated handshake between the aircraft and the Inmarsat satellite communication network.[13]: 40 |

| 06:31 | 07:13 | 23:13 | A ground-to-aircraft telephone call placed by Malaysia Airlines,[18] via the aircraft's satellite link, goes unanswered.[13]: 40 [19]: 18 |

| 06:42 | 07:24 | 23:24 | Malaysia Airlines issues a press statement announcing that Flight 370 is missing.[10] |

| 07:29 | 08:11 | 8 March | The last successful automated hourly handshake is made with the Inmarsat satellite communication network.[13]: 41 [20] |

| 00:11 | |||

| 07:37 | 08:19:29 | 00:19:29 | The aircraft sends a "log-on request" (sometimes referred to as a "partial handshake") to the satellite.[22][23] Investigators believe this follows a power failure between the time the engines stopping due to fuel exhaustion and the emergency power generator starting.[13]: 41 [19]: 18, 33 |

| 07:37 | 08:19:37 | 00:19:37 | Following a response from the ground station, the aircraft replies with a "log-on acknowledgement" message at 08:19:37.443. This is the final transmission received from Flight 370.[13]: 41 [19]: 18 |

| 08:33 | 09:15 | 01:15 | The aircraft does not respond to an hourly, automated handshake attempt.[13]: 41 [20] |

March 2014

A search and rescue effort is initiated in Southeast Asia on the morning Flight 370 disappears.[24] Two passengers who boarded with stolen passports raise suspicion in the days after the disappearance, but they were later determined to be asylum seekers.[10][25] On 9 March, some search efforts are launched in the Andaman Sea at the request of Malaysian officials, based on the possibility that the aircraft may have turned back from its flight path;[26] the following day, officials confirm Flight 370 turned back towards Malaysia.[27]

On 15 March, Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak announced that Flight 370 had remained in contact with a satellite communication network for several hours after it disappeared and that the aircraft was last located by military radar over the Andaman Sea. Analysis of these communications indicate the last communication with the aircraft was made when it was along one of two corridors; one stretching northwest to Central Asia and one stretching southwest into the southern Indian Ocean.[28] The northern corridor was soon discounted and a search of a remote region of the southern Indian Ocean, led by Australia, began on 18 March.[29] On 24 March, Malaysia Airlines and Najib announced that the flight had ended in the Southern Indian Ocean without survivors.[30]

Malaysia Airlines confirms that flight MH370 has lost contact with Subang Air Traffic Control at 2.40am, today (8 March 2014). Flight MH370, operated on the B777-200 aircraft, departed Kuala Lumpur at 12.41am on 8 March 2014. MH370 was expected to land in Beijing at 6.30am the same day. The flight was carrying a total number of 227 passengers (including 2 infants), 12 crew members. Malaysia Airlines is currently working with the authorities who have activated their Search and Rescue team to locate the aircraft.

First press release from Malaysia Airlines, 7:24 8 March (UTC+8)[10]

- 8 March

- At 5:30, the Aeronautical Rescue Coordination Centre (ARCC) at the Kuala Lumpur Area Control Center is activated.[31] A search-and-rescue effort is initiated in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand around the location at which Flight 370 lost contact with air traffic control.[32]

- At 7:24, Malaysia Airlines issues a press statement saying contact with Flight 370 had been lost at 2:40—later changed to 1:30—and that a search and rescue effort had been initiated. After contacting the passengers' and crew's families, the passenger manifest is released.[10][24]

- In the morning, after the announcement of Flight 370s disappearance, the Royal Malaysian Air Force reviews data collected by military radar. They find that an unidentified aircraft, later determined to be Flight 370, had crossed the Malay Peninsula and was tracked until it left their radar's range at 2:22 while over the Andaman Sea.[19]: 2 [33][34] The satellite communications are not noticed until the following day and are not publicly disclosed for several days,[35] while the radar data is not immediately acknowledged.[36]

- Austria and Italy confirm that two people listed on the passenger manifest—one from each country—were not on the flight. Both men's passports had been stolen in Thailand within the last two years.[37]

- The US National Transportation Safety Board sends a team of investigators to Malaysia.[32]

- Inmarsat hands over its data regarding communications with Flight 370 in response to a request from SITA, the company providing the datalink for Flight 370's communications equipment.[21][35]

- 9 March

- By the end of the day, 40 aircraft and more than 24 vessels from several nations are involved in the search.[32] Thailand's navy shifts the focus of its search to the Andaman Sea at the request of Malaysia. The Chief General of the Royal Malaysian Air Force announces that Malaysia is focused on a recording of radar and there is a "possibility"[26] that Flight 370 turned around and travelled over the Andaman Sea.[26][32]

- Malaysia Airlines sends a team of more than 150 senior managers and caregivers to Beijing (most passengers were from China), where a centre is established for families of those on board to be comforted and await the latest news from the airline. A similar centre is opened in Kuala Lumpur. Malaysia Airlines also announces they are beginning to provide financial assistance to the families of those on board and are offering to transport them to Kuala Lumpur.[10]

- INTERPOL confirms the passports of the Austrian and Italian men were registered in its database of stolen passports and that no query of the database was made.[38] Officials investigate CCTV video of these passengers taken before they boarded the flight. There are concerns about a possible link to terrorism, but officials say no such links have been found.[32]

- 9–11 March

- Staff at Inmarsat look at the data they received from Flight 370 to determine whether they can assist the search. They find the aircraft continued flying for several hours after it lost contact with air traffic control and analyse it to determine the aircraft's location. By the morning of 11 March, they determine the aircraft was last located along one of two arcs and share the information with Malaysian investigators.[35]

- 10 March

- The Royal Malaysian Air Force confirms Flight 370 made a "turn back".[27]

- 11 March

- Malaysian police announce the two passengers using stolen passports were Iranian men who were likely migrants trying to emigrate to Germany. The tickets for both passengers ended in Frankfurt. The head of INTERPOL says, "the more information we get, the more we are inclined to conclude it is not a terrorist incident".[25]

- China activates the International Charter on Space and Major Disasters to aggregate satellite data to aid the search.[39][40]

- Inmarsat provides Malaysia with an initial analysis of the communications with Flight 370. Malaysia discusses the information with US investigators and agrees to allow the US to investigate the Inmarsat data.[35] New Scientist publishes an article saying Flight 370 "sent at least two bursts of technical data back to the airline before it disappeared".[41]

- 12 March

- Malaysian officials announce an unidentified aircraft, possibly Flight 370, was last located by military radar at 2:15 in the Andaman Sea, 320 kilometres (200 mi) north-west of Penang Island and near the limits of the military radar's coverage.[36]

- 13 March

- An article published by the Wall Street Journal says Flight 370 continued to fly for hours after it was last seen by air traffic control, citing undisclosed US investigators. The article originally states that messages about engine performance continued to be sent to engine manufacturer Rolls-Royce; the newspaper soon corrects the article to say the claim is "based on analysis of signals sent by the Boeing 777's satellite-communication link ... the link operated in a kind of standby mode and sought to establish contact with a satellite or satellites. These transmissions did not include data."[42] Malaysia denies the report.[43]

- Speaking at a press conference, White House spokesman Jay Carney says, "It is my understanding that based on some new information that's not necessarily conclusive—but new information—an additional search area may be opened in the Indian Ocean".[43]

- China criticizes Malaysia's handling of the search coordination and the flow of information.[43]

- 14 March

- Inmarsat publicly acknowledges they recorded transmissions from the aircraft for several hours after it disappeared from air traffic control over the South China Sea.[44]

- Malaysia Airlines retires the MH370/MH371 flight number pair and begins using MH318/MH319.[10][45]

- 15 March

- In a press conference, Malaysian PM Najib confirms Flight 370 remained in contact with Inmarsat's satellite communication network for several hours after it was lost by air traffic control. He says the ACARS messaging system was disabled early in the flight but the final satellite communication was made at 8:11. The final communication was made along one of two arcs; a "northern corridor" stretching from northern Thailand to Kazakhstan and a "southern corridor" from Indonesia into the southern Indian Ocean. Najib says the search in the South China Sea will be ended and the deployment of assets re-assessed. Malaysia sends diplomatic notes to all of the countries along the two corridors.[10][28][46]

- A team from Inmarsat arrives in Malaysia to assist in the investigation, which involves Malaysia, the US and the UK.[10]

- Investigators visit the homes of both pilots. A flight simulator in the home of Captain Shah is confiscated. Malaysian police chief Khalid Abu Bakar says it was the first visit to the pilots' homes but officials later say they visited the pilots' homes on 9 March.[10][11]

- 17 March

- Australia agrees to lead the search along the southern corridor in the southern Indian Ocean, which mostly lies within Australia's concurrent aeronautical and maritime search and rescue regions.[47][48][49] A shipping broadcast requesting assistance in the search is made.[29][50]

- 18 March

- Australia conducts its first aerial search of the southern Indian Ocean,[51] 2,500 kilometres (1,600 mi) south-west of Perth. The search area was determined by the US National Transportation Safety Board and is approximately 600,000 square kilometres (230,000 sq mi) in size.[29]

- 19 March

- The search area is revised to approximately 305,000 km2 (118,000 sq mi) about 2,600 kilometres (1,600 mi) south-west of Perth. Three merchant ships have joined the search.[29][52]

- 20 March

- Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott announces that satellite imagery taken on 16 March appears to show two large objects floating in the ocean 2,500 km (1,600 mi) south-west of Perth. The images,[53][54] taken by Digital Globe and analysed by the Defence Imagery and Geospatial Organisation, show objects that appear to be 24 m (79 ft) and 5 m (16 ft) in length at 44°03′02″S 91°13′27″E / 44.05056°S 91.22417°E.[55][56]

- Aircraft are dispatched to the area of the satellite images but do not find the objects. HMAS Success and a merchant vessel are en route to the area, joining a merchant vessel already there. Six merchant vessels have assisted in the search since a shipping broadcast was made on 17 March.[50]

- 22 March

- Officials announce that images captured by a Chinese satellite on 18 March shows a possible object measuring 22.5 by 13 metres (74 by 43 ft) at 44°57′29″S 90°13′43″E / 44.95806°S 90.22861°E, approximately 3,170 kilometres (1,970 mi) west of Perth and 120 kilometres (75 mi) from the earlier sighting.[55]

Using a type of analysis never before used in an investigation of this sort...Inmarsat and the AAIB have concluded that MH370 flew along the southern corridor, and that its last position was in the middle of the Indian Ocean, west of Perth. This is a remote location, far from any possible landing sites. It is therefore with deep sadness and regret that I must inform you that, according to this new data, Flight MH370 ended in the southern Indian Ocean.

Prime Minister of Malaysia Najib Razak

- 24 March

- Malaysia's Prime Minister Najib Razak announces at a press conference at 22:00 local time (Malaysia) that Flight 370 is presumed to have gone down in the southern Indian Ocean with no survivors. Shortly before Najib's announcement, Malaysia Airlines tells families it assumes "beyond reasonable doubt" there are no survivors.[30]

- The search area is narrowed to the southern part of the Indian Ocean to the west and south-west of Australia. The northern search corridor north-west of Malaysia and the northern half of the southern search corridor—the waters between Indonesia and Australia—are definitively ruled out. An Australian search aircraft spots an "orange rectangular object"[57] and a "gray or green circular object"[57] 2,490 km (1,550 mi) south-west of Perth.[57]

- 25 March

- Around 200 relatives of Flight 370 passengers protest outside the Malaysian embassy in Beijing; a rare event in China. Among the angry, distraught relatives' chants are "Liars!"[58] and "Tell the truth! Return our relatives!"[58][59] China demands Malaysia hand over the satellite data that led them to determine that Flight 370 ended in the southern Indian Ocean with no survivors. China sends a special envoy to Malaysia.[60][61]

- 26 March

- Officials announce that images captured by a French satellite on 23 March appear to show about 122 floating objects up to 23 m (75 ft) in length at 44°41′24″S 90°25′19.20″E / 44.69000°S 90.4220000°E, 44°41′38.45″S 90°29′31.20″E / 44.6940139°S 90.4920000°E and 44°40′10.20″S 90°36′25.20″E / 44.6695000°S 90.6070000°E, which is about 930 km (580 mi) north of the earlier satellite observations.[55][62][63]

- The UK Air Accidents Investigation Branch (AAIB) announces they have appointed an accredited representative to join the investigation team in Malaysia. As the state of manufacture of the aircraft's engines (UK manufacturer Rolls-Royce), the AAIB is authorized to join the investigation by ICAO protocol.[64][65]

- 27 March

- Officials reveal that images captured by a Thai satellite on 24 March appear to show about 300 floating objects 2–15 m (6 ft 7 in – 49 ft 3 in) in size. The possible objects are about 2,700 km (1,700 mi) south-west of Perth and about 200 kilometres (120 mi) south of the French observations.[55][66]

- 28 March

- The search shifts to a new 319,000-square-kilometre (123,000 sq mi) area around 1,100 kilometres (680 mi) north-east of the previous search area.[29][67]

- 29 March

- Malaysia announces that an international panel will be formed to investigate the Flight 370 incident.[68]

- 30 March

- The Joint Agency Coordination Centre (JACC), headed by Angus Houston, is established to coordinate the search effort. It becomes operational the following day and assumes the role of coordinating the search effort and communicating with media, foreign governments, and between Australian government agencies from the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA).[29][69]

April – May 2014

In early April, an intense effort—the "acoustic search"— was made to detect the acoustic signals generated by underwater locator beacons (ULBs, also known as "pingers") attached to the flight recorders on Flight 370. After immersion in water, the ULBs emit an acoustic signal (also called a "ping") at a specific frequency once per second and have a battery life of 30–40 days. Three vessels, including one submarine and a vessel employing a towed pinger locator, tried to detect the acoustic signal along the 7th BTO arc—the centreline of the southern corridor—until 14 April, detecting several possible pings. Analysis of these signals determined they did not match the nominal characteristics of the ULBs; although unlikely, experts determine they may have originated from a damaged ULB. A sonar search of the seafloor begins on 14 April. A search of the ocean surface by aircraft and vessels ends on 28 April and the sonar search—the seafloor sonar survey—ends on 28 May, finding no debris from Flight 370.[19]: 1, 11–14 In late May, work on a bathymetric survey begins in preparation for the next phase of the search.[70][71]

In early April, Malaysia submits a preliminary report to the ICAO, which is publicly released on 1 May along with recordings of conversations between Flight 370 and air traffic control.[16][72] On 27 May, the complete log of transmissions between Flight 370 and Inmarsat via satellite are released, following weeks of public pressure.[73]

- 1 April

- The International Air Transport Association (IATA), a major industry trade group, announces it will form a task group to enhance aircraft tracking to ensure further aircraft disappearances cannot happen.[74][75]

- 2 April

- The Royal Navy survey vessel HMS Echo makes a possible ULB detection. After tests the following day, the detection is determined to be an artefact of the ship's sonar system.[19]: 11

- The ADV Ocean Shield deploys the first of its two towed pinger locators (TPLs).[19]: 11

- 5 April

- Haixun 01 makes another possible ULB detection about 3 km (1.9 mi) west of the previous day's detection and near 25°S 101°E / 25°S 101°E.[76][77] Neither detection was recorded.[76] HMS Echo and a submarine were later tasked to the location of the Haixun 01's detections, but unable to make any detections.[19]: 11 It was determined the depth of the seafloor, surface noise and the equipment used by Haixun 01 made it unlikely the detections were from ULBs.[19]: 13

- The ADV Ocean Shield deploys its second TPL, after the first exhibited problematic acoustic noise. Two detections are made.[d] The first detection, made while the TPL was descending, lasted over two hours before it was lost. This detection was made at 33 kHz, while the ULBs on Flight 370's flight recorders emit a pulse at 37.5±1kHz. When the vessel passed the location in the opposite direction, a second detection lasting 13 minutes was made. Houston calls this the "most promising lead"[79] thus far in the search.[78][79]

- Malaysia reorganizes its investigation team to consist of an airworthiness group, an operations group, and a medical and human factors group. The airworthiness group will examine issues related to maintenance records, structures and aircraft systems. The operations group will review flight recorders, operations and meteorology. The medical and human factors group will investigate psychological, pathological and survival factors. Malaysia also announces it has set up three ministerial committees—a Next of Kin Committee, a committee to organise a Joint Investigation Team, and a committee responsible for Malaysian assets deployed in the search effort.[80]

- 6 April

- It has now been 30 days since Flight 370 presumably crashed in the southern Indian Ocean; the minimum battery life of the ULBs on Flight 370's flight recorders. The manufacturer of the ULBs predicts the maximum battery life is about 40 days.[19]: 11

- 6–16 April

- Sorties flown by Royal Australian Air Force AP-3C Orion aircraft deploy sonobuoys in locations near the 7th BTO arc where water depths are favourable for detection by sonobuoy. Sonobuoys float on the surface and release a hydrophone that descends 300 m (1,000 ft) and can detect ULB signals up to 4,000 m (13,000 ft) below the surface. Each sortie can deploy up to 84 sonobuoys capable of searching around 3,000 km2 (1,200 sq mi). A possible ULB detection is made on 10 April with a sonobuoy close to the location of the ADV Ocean Shield; this is quickly determined to be unrelated to Flight 370's ULBs.[19]: 13, 15 [78]

- 8 April

- ADV Ocean Shield makes two possible ULB detections, close to those of 5 April, lasting about five and a half minutes and seven minutes.[e] The following day, Houston says the acoustic search will continue for as long as feasible because more and better quality detections will better pinpoint the aircraft's location—if indeed the detections were from Flight 370's ULBs. He also says the batteries will expire soon and the TPL can search six times more seafloor per day than the autonomous underwater vehicle carried aboard ADV Ocean Shield.[78][81]

- 9 April

- Malaysia submits a five-page preliminary report to the International Civil Aviation Organization, the United Nation's civil aviation body.[16] The report, dated 9 April but not publicly released until 1 May, includes a call for better tracking technology for commercial aircraft.[72][82]

- 10 April

- A sonobuoy deployed near ADV Ocean Shield makes a possible ULB detection. The following day, officials say the detection is unlikely to be related to Flight 370.[83]

- 13 April

- An oil slick is found 5.5 km (3.4 mi) from possible ULB detections made by the ADV Ocean Shield.[84][85] On 17 April, the JACC announces that tests of samples from the oil slick detected neither jet fuel nor hydraulic fluid.[85][86]

- 14 April

- The ULBs have now been underwater for 38 days.[87] Considering their batteries last 30–40 days[19]: 11 and that no possible detections have been made in almost a week, ADV Ocean Shield stops searching with the TPL and deploys a Bluefin-21, a torpedo-shaped autonomous underwater vehicle equipped with side-scan sonar, to scan the seafloor in the vicinity of the possible ULB detections. Analysis of the detections by the ADV Ocean Shield determine they do not match the nominal characteristics of the ULBs. Experts determine that although unlikely, they may have originated from a damaged ULB. The decision is made to search the seafloor in the vicinity of the detections (near 21°S 104°E / 21°S 104°E).[19]: 13–15 During this new phase of the search—the seafloor sonar survey— the Bluefin-21 will be deployed with a programmed area to scan. Each mission scans about 40 km2 (15 sq mi) of seafloor and takes about 24 hours; two hours to descend, 16 hours spent scanning the seafloor and two hours to return to the surface. Once back at the surface, it is recovered. It takes about four hours to change the batteries and download data from the mission, which is analysed aboard the ADV Ocean Shield.[87][88] The first mission ends prematurely when the Bluefin-21 reached its maximum operating depth; it needs to be about 50 m (160 ft) above the seafloor to obtain a reliable image.[89]

- 23 April

- A metal object, appearing to be a piece of riveted sheet metal, washes up on the Western Australian coast, 10 km (6.2 mi) east of Augusta. The next day the ATSB determines that the object is unrelated to Flight 370.[90][91]

- 28 April

- The surface search ends. In a press conference, Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott says any debris would likely have become waterlogged and sunk and that the aircraft involved in the surface search were "operating at close to the limit of sensible and safe operation".[6] The surface search in Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean lasted 52 days, during 41 of which Australia coordinated the search. Over 4,500,000 km2 (1,700,000 sq mi) of ocean surface was searched. In the Southern Indian Ocean, 29 aircraft from seven countries conducted 334 search flights; 14 ships from several countries were also involved. Although the seafloor sonar survey will continue, Abbott says plans for the next phase of the search, which will involve commercial companies and use towed sonar to more easily scan large areas of seafloor, are being developed.[6][92][93]

- 1 May

- The interim report submitted earlier by Malaysia to the ICAO, dated 9 April, is released publicly, along with Flight 370's cargo manifest and seating plan, audio recordings and a transcript of communications between Flight 370 and Malaysian air traffic control.[16][72][82]

- 2–22 May

- The seafloor sonar survey is suspended on 2 May as the AVD Ocean Shield returns to port to replenish supplies and personnel.[94] Within two hours of its first deployment after returning to the search area on 13 May, Bluefin-21 develops a communications problem and is recovered.[95] Spare parts from the UK were required and the AVD Ocean Shield returned to port to collect the parts.[96] The problem is fixed and the seafloor sonar survey resumes on 22 May.[70]

- 5 May

- A tripartite meeting to discuss the next phase of the search is held with representatives from Australia (Warren Truss, Minister for Infrastructure and Regional Development), Malaysia (Hishammuddin Hussein, Defence Minister and acting Transport Minister), and China (Yang Chuantang, Transport Minister). During the press conference, Truss announces the US Navy has extended the contract for Bluefin-21 by four weeks.[97]

- 13 May

- The Wall Street Journal publishes a commentary by Malaysian PM Najib, who defends Malaysia's response to the disappearance of Flight 370 and acknowledges his government "didn't get everything right".[98]

- 21 May

- The Chinese vessel Zhu Kezhen leaves Fremantle to begin conducting the bathymetric survey.[70] Because available bathymetric data for the area is of poor resolution, the survey is necessary for the safe operation of towed equipment that will be used during the next phase of the search.[71][99]

- 27 May

- Malaysia releases the complete log of transmissions between Flight 370 and Inmarsat via satellite after weeks of public pressure.[73]

- 28 May

- The seafloor sonar survey is completed. After 30 deployments of the Bluefin-21 to depths of 3,000–5,000 m (9,800–16,400 ft), which scanned 860 km2 (330 sq mi) of seabed, no objects associated with Flight 370 were found. The following day, after analysis of data from the last mission, the ATSB announces the search in the vicinity of the acoustic detections is complete and the area can be discounted as the final location of Flight 370.[7][100]

June – September 2014

During this time, preparations are made for the next phase of the search, which was initially scheduled to begin in August,[101] but did not commence until early October.[102] On 26 June, Australia announces details for the next phase of the search—named the "underwater search"—despite the previous underwater towed pinger locator search and sonar survey. A bathymetric survey, begun in May, is necessary to map the seafloor topography before the underwater search.[101] On 6 August, Australia awards a A$50 million tender to conduct the underwater search to Fugro; Malaysia is also contributing assets to the underwater search.[103][104]

- 4 June

- A recording of an underwater sound that could have been that of Flight 370 hitting the water is released by researchers from Curtin University.[105] The researchers believe the sound is probably unrelated to Flight 370.[19]: 47 The lead researcher believes there is a small chance—perhaps 10 percent—that the acoustic event is related to Flight 370.[106]

- Australia opens the tender process for the underwater search. Bidders may submit proposals until 30 June.[107]

- 10 June

- The ATSB hires Fugro, which will use the MV Fugro Equator, which will conduct the bathymetric survey alongside the Zhu Kezhen.[107]

- 12 June

- The head of the Malaysian government committee to handle the needs of families of Flight 370 passengers announces that families of missing passengers will receive US$50,000 per person as an interim compensation.[108]

- 26 June

- The ATSB releases a report, MH370 – Definition of Underwater Search Areas,[19] discussing the methodology used to determine a new search area along the 7th BTO arc determined by the aircraft's communication with the Inmarsat satellite. The search will prioritise an area of approximately 60,000 km2 (23,000 sq mi). A bathymetric survey of the region, already underway, will take around three months to complete. The new underwater search is expected to begin in August. Australia and Malaysia are working on a Memorandum of Understanding to cover financial and co-operation arrangements for search and recovery activities.[101] Among other details, the ATSB report concludes an unresponsive crew or hypoxia event "best fit the available evidence"[19]: 34 for the five-hour period of the flight as it travelled south over the Indian Ocean,[19]: 34 likely on autopilot.[109][110]

- 17 July

- Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 is shot down in a rebel-controlled area of Ukraine. Malaysia's Defence Minister assures the public that the additional incident will not detract from Malaysia's commitment to the search for Flight 370.[111]

- 21 July

- Angus Houston, the head of the JACC, is appointed as Australia's special envoy in Ukraine to recover and repatriate bodies of Australian victims and ensure that a proper investigation of the crash of Flight 17 is initiated in accordance with international standards.[112][113] Around this time, Houston leaves the agency;[114] Deputy Coordinator Judith Zielke assumes leadership of the JACC and is later appointed its Chief Coordinator.[115][116]

- 6 August

- Australia awards Fugro a A$50 million (US$46,6 million)[117] contract to conduct the underwater search. Malaysia also commits vessels to the bathymetric survey and underwater search effort.[103][104]

- 8 August

- Khazanah Nasional—the majority shareholder (69.37 percent)[118] and a Malaysian state-run investment arm—announces its plan to purchase the remainder of the airline, thereby renationalising it. The move has been anticipated because of the airline's poor financial performance, which has been exacerbated by the combined effect on consumer confidence of the loss of Flights 370 and 17.[119][120][121]

- 14 August

- An HSBC employee and her husband are arrested for allegedly siphoning 111,000 Malaysian ringgit (US$35,000)[122] from bank accounts of several Flight 370 passengers in July.[123]

- 20 September

- The Zhu Kezhen finishes bathymetric survey operations and begins its return passage to China.[124]

October 2014 – June 2015

The underwater search commences on 6 October.[102] The search involves four vessels: the GO Phoenix (6 October–20 June),[102][125] Fugro Discovery (joined search 23 October),[124] Fugro Equator (joined search 15 January),[126] and Fugro Supporter (29 January–early May).[127][128] The bathymetric survey was suspended on 17 December for the only remaining ship performing the survey, the Fugro Discovery, to be refitted to join the underwater search. During the bathymetyric survey, 208,000 km2 (80,000 sq mi) of seafloor was charted.[8]

On 8 October, the ATSB releases a report on the latest analysis of satellite communications, determining that the most likely location of the aircraft is south of the priority area identified in June. Officials say the search will begin in the area determined in the report. One year after the flight's disappearance, Malaysia declares Flight 370 an accident in accordance with the Chicago Convention in January 2015[129][f] and releases an interim report about Flight 370, focusing on factual information.[12][130]

- 6 October

- The underwater search begins. GO Phoenix, which left port at Jakarta on 24 September, begins work about 1,800 km (1,100 mi) west of Western Australia.[102][131][132]

- 8 October

- Officials announce that the priority area to be searched is south of the area identified in the June ATSB report.[133] The ATSB releases a supplement to the June report detailing the methodology behind refinements to the analysis of satellite communications, which resulted in the shift of the priority search area.[134][135]

- A peer-reviewed paper is published online by the Journal of Navigation—a journal of the Royal Institute of Navigation—by Inmarsat scientists who analysed the communications with Flight 370. The paper details the methodology of the calculations and the way continual changes, especially during the first few weeks of the search, resulted in the shifting search zones. It was released as an open access article with a Creative Commons Attribution license.[136]

- 23 October

- Fugro Discovery commences search operations.[124]

- 26 October

- Fugro Equator ends its bathymetric survey operations and leaves for Fremantle, where it will be refitted and mobilised to join GO Phoenix and Fugro Discovery in the underwater search. Over 150,000 km2 (58,000 sq mi) of seafloor have been surveyed. If necessary, bathymetric survey operations may recommence in the future.[124]

- 16 November

- Fugro Equator leaves Fremantle to resume work on the bathymetric survey after the arrival of equipment needed for the underwater search is delayed.[137]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

- 19 November

- The JACC releases a video explaining the work being carried out and the complexities of the underwater search.[137]

- 17 December

- Fugro Equator finishes bathymetric survey work and leaves for Fremantle, where it will be refitted for the underwater search. The bathymetric survey charted 208,000 km2 (80,000 sq mi) of seafloor. The ATSB releases a video titled Bathymetry of the MH370 Search Area, which presents a visualisation of the bathymetric data collected in the search area.[8]

- 18 January

- Search operations are suspended due to 5–6 m (16–20 ft) waves caused by Tropical Cyclone Bansi. The search fully resumes by 23 January.[126]

- 22 January

- The ATSB calls for expressions of interest for operations to recover Flight 370 so a recovery effort can be quickly and effectively mobolised if and when debris from the aircraft is located. The request will allow the ATSB to determine which organisations can supply equipment and expertise for the recovery effort.[139]

- 29 January

- In accordance with Annexes 12 and 13 to the Chicago Convention, the Malaysian government officially declares the disappearance of Flight 370 an accident with no survivors.[f][129]

- A fourth vessel, MV Fugro Supporter, joins the underwater search.[127] It is equipped with a Kongsberg HUGIN 4500 autonomous underwater vehicle and will be able to search areas which cannot be effectively searched by the towfish used by the other vessels.[141][142]

- 1 February

- Search operations are suspended due to effects of tropical cyclone Eunice and ex-tropical cyclone Diamondra, which are causing ocean conditions up to sea state 8 with waves of 9–14 m (30–46 ft). Search operations are resumed on 5 February by Fugro Equator, 8 February by Fugro Discovery, and 9 February by Fugro Supporter.[g][127][143]

- 8 March

- On the first anniversary of the flight's disappearance, Malaysia's Ministry of Transport releases an interim report that is required by international protocol.[12] The report focuses on factual information rather than analysis of possible causes of Flight 370's disappearance. One significant issue, not previously revealed publicly, is that the battery in the underwater locator beacon attached to the flight data recorder had expired in December 2013, which may have compromised its performance.[12][130][144]

- 17 March

- The search resumes after being suspended for several days because of poor weather associated with ex-Tropical Cyclone Haliba.[145]

- 2 April

- Fugro Discovery leaves port in Fremantle with a new towfish named Intrepid. After calibration trials at sea, the vessel will leave for the search area on 5 April.[146]

- 16 April

- A tripartite meeting between Malaysian, Australian and Chinese officials is held. Over 60 percent of the 60,000 km2 (23,000 sq mi)[147] priority search area has been searched. Excluding significant delays, the search of the priority search area will be completed around May 2015.[148] The officials agree that if no trace of the aircraft is found in the priority search area, the underwater search will be extended to an additional 60,000 km2 (23,000 sq mi) of adjacent seafloor.[147][149][150]

- Angus Houston was appointed Knight of the Order of Australia in recognition of his military service and his "continued commitment to serve the nation in leadership roles, particularly the national responses to the [Malaysia Airlines Flight 370] and [Malaysia Airlines Flight 17] disasters".[151][152]

| External images | |

|---|---|

- Early May

- Fugro Supporter withdraws from the underwater search and travels to Fremantle, where the autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) it operated is offloaded. Sea conditions during the austral winter are too rough to safely launch and recover the AUV and therefore, AUV operations will be suspended during the winter months. However, the AUV will be kept ready to assist the search at short notice.[128]

- 13 May

- The JACC and ATSB announce the discovery of a shipwreck 12 nmi (22 km; 14 mi) east of the seventh BTO arc at a depth of 3,900 m (12,800 ft). Fugro Equator detected a cluster of small objects in an otherwise featureless region of seafloor. It was classified as a "Class 2" feature "of potential interest but unlikely to be related to MH370".[153] Fugro Supporter was sent to investigate the site with its AUVs. A high-resolution sonar scan reveals many small objects, the largest of which is rectangular and 6 m (20 ft) on its longest side. Another AUV mission photographed the debris field, revealing the shipwreck and a field of cricket ball-sized coal. The images are sent to marine archaeologists to identify the wreck.[128][153]

- 30 May–6 June

- Search operations are suspended due to rough ocean conditions, including average wave heights of 6 m (20 ft).[154][155]

- 3–16 June

- Go Phoenix leaves the search area to return to port. The supporting frame of the vessel's towfish system was damaged while on the vessel's deck during rough seas; the vessel's supply of gasses for welding was exhausted before repairs could be completed.[155] Repairs were completed and the vessel left port on 10 June, arriving in the search area on 16 June.[156]

- 20 June

- GO Phoenix departs the search area to begin passage to Singapore, where it will be demobilized from search activities.[125]

July 2015 – January 2017

On 29 July, a piece of marine debris is found on Réunion—an island in the western Indian Ocean—that resembled an aircraft component. The object is confirmed to be a flaperon from a Boeing 777. A search of the island and nearby waters is launched to locate other possible debris from Flight 370. Other marine debris found on Réunion over the following days is suspected of originating from Flight 370, but only the flaperon is conclusively linked to Flight 370. On 5 August, Malaysia's Prime Minister confirms that the first object discovered is from Flight 370; confirmation from French officials comes on 3 September. In the subsequent months several pieces of debris are determined to be highly likely to have come from Flight 370.

On 17 January 2017 the underwater search for Flight 370 is suspended after a survey of 120,000 km2 (46,000 sq mi) of the Indian Ocean is unsuccessful in locating the plane.

- 29 July

- A piece of marine debris resembling an aircraft flaperon, and a suitcase are found on a beach on Réunion, a French island in the western Indian Ocean about 4,000 km (2,500 mi) west of the underwater search area.[157][158][159] The items are transported the following day to Toulouse, France for analysis.[160]

- 31 July

- A Chinese water bottle and an Indonesian cleaning product are found on Réunion in the vicinity of the location where the aircraft flaperon and suitcase were found.[161][162]

- 2 August

- The Malaysian Ministry of Transportation announces that the first object discovered is a flaperon from a Boeing 777; they state that the verification was made with investigators from France, Malaysia, Boeing, and the US NTSB.[163]

- 5 August

- The Malaysian Prime Minister announces that experts have "conclusively confirmed"[164] that the flaperon found on 29 July is from Flight 370; the debris is the first physical evidence that Flight 370 ended in the Indian Ocean.[164]

- 6 August

- Malaysia's Transport Ministry claims that window panes and aircraft seat cushions have washed up on Réunion.[165] This claim is disputed by France.[166]

- 7 August

- Maldivian police investigate claims that plane debris has washed up on North Malé Atoll, Maldives.[167] Authorities in nearby Mauritius have also begun searching for debris[168] and sent a piece of a bag found on Îlot Gabriel for inspection.[169]

- 12 August

- A packet of Malaysian noodles were found in South Australia and a Malaysia Airlines baggage tag was found in Nowra, New South Wales. The items were turned into Australian authorities, who noted that "It’s very challenging for investigators to find something that can be linked to the aircraft – it would really have to be some form of debris from the aircraft. But we encourage people to bring anything unusual or out of place forward. It’s far better that we investigate and rule it out."[170]

- The debris from North Malé is flown to Malaysia for investigation.[171]

- Malaysia's government news agency published a new theory that Flight 370 made a soft landing on the water, floated for a while on the surface, and then sank mostly in one piece. Many experts also believe in this theory.[172]

- 3 September

- French investigators affirm "with certainty" that the aircraft flaperon discovered on 29 July is from Flight 370, due to a serial number that matched the records of the Spanish manufacturer that produced portions of the flaperon.[173][174]

- 8 September

- Australia's Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) releases a drift analysis that concludes that the finding of the flaperon on Réunion is consistent with the current search area for Flight 370.[175]

- 3 December

- The ATSB publishes a report, based on analysis by Australia's Defence Science and Technology Group (DST Group). The analysis determined that the most probable location of Flight 370 when it entered the water is within the southern half of the existing search zone. The JACC also releases a pre-publication draft of Bayesian methods in the search for MH370, a book by the DST Group detailing their analysis.[176][177]

- Australian Deputy Prime Minister Warren Truss announces the number of vessels in the search would be doubled to four, and that the undersea search was expected to be completed by June 2016.[178]

- 5 December

- The MV Havila Harmony arrives in the search area, becoming the third vessel actively involved in the search. The Havila Harmony is carrying an AUV that will be deployed to search the most challenging underwater terrain.[179][180]

- 19 December

- A second 19th-century shipwreck is discovered.[181]

- 2 January 2016

- The AUV aboard the MV Havila Harmony is used to produce a high-resolution sonar image of an "anomalous sonar contact" made on 19 December that analysis suggested to be man-made and possibly a shipwreck. The AUV sonar imagery confirms the object is a shipwreck.[182]

- 24 January

- The towfish being used by the Fugro Discovery collides with an undersea mud volcano. The towing cable breaks and the towfish along with 4,500 metres of towing cable sink to the seafloor.[183][184]

- 29 January

- Australia announces that a fourth ship will join the search. The Dong Hai Jiu 101 is being supplied by China and will employ a towfish operated by Phoenix International Holdings and Hydrospheric Solutions, both companies with previous experience in the search for Flight 370. The ship is expected to join the search in late February.[185]

- 2 March

- Media report the discovery of an object, a suspected horizontal stabilizer, found on a sandbar in Mozambique, that may have originated from a Boeing 777. The object, found by an American tourist the preceding weekend, is flown to Australia for examination.[186]

- 24 March

- Australian Transport Minister Darren Chester announces that two pieces of debris, the object reported discovered earlier in March as well as an object found in Mozambique by a South African tourist in December 2015, are both "almost certainly" from MH370.[187]

- Part of an engine cowling is found on the coast of South Africa.[188]

- 2 April

- A piece of debris that is suspected to be a bulkhead from inside the cabin of an aircraft is discovered on the coast of Rodrigues, an autonomous island in Mauritius.[189][190]

- 12 May

- Malaysian Transport Minister Liow Tiong Lai announces that the engine cowling discovered on 24 March in South Africa and the bulkhead discovered on 2 April in Rodrigues are "almost certainly" from Flight 370.[191]

- 24 June

- The Australian Transport Minister, Darren Chester, said that a piece of aircraft debris was found on Pemba Island, off of the coast of Tanzania.[192] It was handed over to the authorities so that experts from Malaysia can determine whether it is part of the aircraft.[193] The Australian government released photos of the piece, believed to be an outboard wing flap, on 20 July.[194]

- 22 July

- A meeting of senior ministers from Australia, China, and Malaysia is held in Putrajaya, Malaysia. Less than 10,000 km2 (3,900 sq mi) of the 120,000 km2 (46,000 sq mi) high priority search area remains to be searched. The ministers agree that if no credible new evidence pointing to a particular location where the aircraft may be is found, the search will be suspended after the 120,000 km2 (46,000 sq mi) high priority search area is completely searched.[195] Fugro, the survey company hired to search for the plane, believe that the wrong area may have been targeted.[196]

- 27 July

- Scientists from the Euro-Mediterranean Center on Climate Change publish a paper analysing where wreckage was found with ocean drift. This predicted an area for the crash site, further north than the ATSB search area.[197][198]

- 15 September

- Malaysia's transport ministry confirms that the outboard wing flap discovered on 24 June on Pemba Island originated from Flight 370, due to identifying part numbers and date stamps.[199]

- 20 December

- The ATSB releases a report suggesting a new 25,000 km2 (9,700 sq mi) search area north of the current search area. The report noted that "if this area were to be searched, prospective areas for locating the aircraft wreckage, based on all the analysis to date, would be exhausted."[200] However, the Australian government stated that the search would not be extended beyond the current search area without new evidence.[201]

- 17 January 2017

- The underwater search for the wreckage of Flight 370 is officially suspended after the survey of 120,000 km2 (46,000 sq mi) of the southern Indian Ocean fails to recover the plane.[9] The search is reported to have cost $160 million.[202]

Notes

- ^ The flight is also known as MH370 or Flight MH370. MH is the IATA designator for Malaysia Airlines and the combination of the IATA designator and flight number is a common abbreviated reference for a flight.[1]

- ^ Aircraft altitude is given in feet above sea level and measured, at higher altitudes, by air pressure, which declines linearly as altitude above sea level increases. Using a standard sea level pressure and formula, the nominal altitude of a given air pressure can be determined—referred to as the "pressure altitude". A flight level is the pressure altitude measured in hundreds of feet. For example, flight level 350 corresponds to an altitude at which air pressure is 179 mmHg (23.9 kPa), which is nominally 35,000 ft (10,700 m) but does not indicate the true altitude.

- ^ Voice analysis of recordings between Flight 370 and ATC have determined that the first officer communicated with ATC while the aircraft was on the ground and the captain communicated with ATC after departure.[12]: 21

- ^ The 5 April detections by the ADV Ocean Shield were made at 4:45 and 9:27PM.[78]

- ^ The 8 April detections by the ADV Ocean Shield were made at 4:27PM and 10:17PM.[78]

- ^ a b Despite the March 2014 announcement that Flight 370 ended in the southern Indian Ocean, officials did not change the status of the flight to an "accident" until the 29 January declaration. The move allows families of passengers to proceed with compensation claims.[140]

- ^ MV GO Phoenix suspended operations for a scheduled return to port on 28 January[127] and resumed search activities on 10 February.[143]

References

- ^ "Airline Codes – IATA Designators". Dauntless Jaunter. Pardeaplex Media. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "New missing Malaysian plane MH370 search area announced". BBC News. 26 June 2014. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

The search for the missing airliner is already among most expensive in aviation history.

- ^ "Search for MH370 to be most expensive in aviation history". Reuters. 8 April 2014. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ^ Brown, Sophie (16 June 2014). "MH370: How long will the search continue?". CNN. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ^ "The Hunt for Malaysia Airlines Flight MH370 Continues". Newsweek. Reuters. 6 August 2014. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ^ a b c "Transcript of Press Conference, 28 April 2014". Joint Agency Coordination Centre. 28 April 2014. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- ^ a b "Update on MH370 Search". Joint Agency Coordination Centre. 29 May 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ a b c "MH370 Operational Search Update— 17 December 2014". Joint Agency Coordination Centre. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ^ a b "Search for MH370 suspended". BBC News. 17 January 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "MH370 Flight Incident (Press statements 8–17 March)". Malaysia Airlines. March 2014. Archived from the original on 18 December 2014. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ a b c Mader, Ian (18 March 2014). "MH370: Further confusion over timing of last words". 3 News. MediaWorks New Zealand. Associated Press. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Malaysian ICAO Annex 13 Safety Investigation Team for MH370, Malaysia Ministry of Transport (8 March 2015). Factual Information, Safety Investigation: Malaysia Airlines MH370 Boeing 777-200ER (9M-MRO) 8 March 2014 (PDF) (Report). Malaysia.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Signalling Unit Log for (9M-MRO) Flight MH370" (PDF). Inmarsat. 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016 – via Malaysia Department of Civil Aviation.

- ^ "Pilot: I established contact with plane". New Straits Times. 9 March 2014. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- ^ "MH370 PC live updates / 530 17th March". Out of Control Videos. Archived from the original on 17 March 2014. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

Timing of ACARS deactivation unclear. Last ACARS message at 01:07 was not necessarily point at which system was turned off

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Documents: Preliminary report on missing Malaysia Airlines Flight 370". Malaysia Department of Civil Aviation. Retrieved 22 October 2014 – via CNN.

- ^ Langewiesche, William (July 2019). "What Really Happened to Malaysia's Missing Airplane". The Atlantic.

- ^ a b Watson, Ivan (29 April 2014). "MH370: Plane audio recording played in public for first time to Chinese families". CNN. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

At 2:03 a.m. local time on March 8, the operational dispatch centre of Malaysia Airlines sent a message to the cockpit instructing the pilot to contact ground control in Vietnam, said Sayid Ruzaimi Syed Aris, an official with Malaysia's aviation authority...MH370 did not respond to the message...'At 7:13,' Sayid said, Malaysia Airlines tried to 'make a voice call to the aircraft, but no pickup.'

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u "MH 370 – Definition of Underwater Search Areas" (PDF). Australian Transport Safety Bureau. 26 June 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|lay-url=ignored (help) - ^ a b c "Malaysian government publishes MH370 details from UK AAIB". Inmarsat. 26 March 2014. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- ^ a b Rayner, Gordon (24 March 2014). "MH370: Britain finds itself at centre of blame game over crucial delays". The Telegraph. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- ^ "Missing Malaysia plane: What we know". BBC News. 1 May 2014. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ Keith Bradsher; Edward Wong; Thomas Fuller. "Malaysia Releases Details of Last Contact With Missing Plane". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ a b Rivera, Gloria (7 March 2014). "Malaysia Airlines Flight Vanishes, Three Americans on Board". ABC News. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- ^ a b Budisatrijo, Alice; Westcott, Richard (11 March 2014). "Malaysia Airlines MH370: Stolen passports 'no terror link'". BBC News. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- ^ a b c Sudworth, John; Pak, Jennifer; Budisatrijo, Alice (9 March 2014). "Missing Malaysia Airlines plane 'may have turned back'". BBC News. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ a b "RMAF chief: Recordings captured from radar indicate flight deviated from original route". The Star. 10 March 2014. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ a b Shazwan, Mustafa Kamal (15 March 2014). "MH370 possibly in one of two 'corridors', says PM". The Malay Mail. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f "Search for Malaysia Airlines flight MH370: Timeline of AMSA's involvement". Australian Maritime Safety Authority. Archived from the original on 1 March 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ a b "Malaysia plane: Bad weather halts search for flight MH370". BBC News. 25 March 2014. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- ^ Broderick, Sean (1 May 2014). "First MH370 Report Details Confusion in Hours After Flight Was Lost". Aviation Week. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d e "Vast waters hide clues in hunt for missing Malaysia Airlines flight". CNN. 9 March 2014. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ "Malaysia lets slip chance to intercept MH370". Malaysiakini. Mkini Group. 17 March 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ^ Campbell, Charlie (17 March 2014). "Another Lesson from MH370: Nobody is Watching Malaysian Airspace". Time. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ^ a b c d McLaughlin, Chris (20 March 2014). "Inmarsat breaks silence on probe into missing jet". Fox News (Interview). Interviewed by Megyn Kelly. 5:00–6:30.

- ^ a b Koswanage, Niluksi; Govindasamy, Siva (14 March 2014). "Exclusive: Radar data suggests missing Malaysia plane deliberately flown way off course – sources". Reuters. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ Shields, Michael; Prodhan, Georgina; O'Leary, Naomi; Trevelyan, Mark (8 March 2014). "Two Europeans listed on missing Malaysia flight were not on board". Reuters. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ "INTERPOL confirms at least two stolen passports used by passengers on missing Malaysian Airlines flight MH370 were registered in its databases". Interpol. 9 March 2014. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ Franco, Michael (12 March 2014). "15 space organizations join hunt for missing Malaysian jet". CNET. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ "Missing Malaysia Airlines jet". International Charter on Space and Major Disasters. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ Marks, Paul (11 March 2014). "Malaysian plane sent out engine data before vanishing". New Scientist. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ Pasztor, Andy; Ostrower, Jon (13 March 2014). "U.S. Investigators Suspect Missing Malaysia Airlines Plane Flew on for Hours". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ a b c Daga, Anshuman; Hosenball, Mark (13 March 2014). "Search for Malaysian plane may extend to Indian Ocean – U.S". Reuters. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ Buckley, Chris; Clark, Nicola (14 March 2014). "Satellite Firm Says Its Data Could Offer Location of Missing Flight". New York Times. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ Anwar, Zafira; Nambiar, Predeep (13 March 2014). "Missing MH370: MAS changes flight number for KL-Beijing-KL flights". New Straits Times. Archived from the original on 17 April 2014. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ Mukherji, Biman; Sugden, Joanna (15 March 2014). "India Continues Search for MH370 as Malaysia Ends Hunt in South China Sea". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ Arrangements in Australia, Australian Maritime Safety Authority, archived from the original on 24 February 2015, retrieved 12 November 2014

- ^ "National Search and Rescue Manual – June 2014 edition" (PDF) (PDF). Canberra, Australia: Australia Maritime Safety Authority, on behalf of the Australian National Search and Rescue Council. June 2014. p. 231. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 April 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|lay-url=ignored (help) - ^ "Search operation for Malaysian airlines aircraft" (PDF). Australian Maritime Safety Authority. 17 March 2014.

- ^ a b "Search operation for Malaysian airlines aircraft: Update 7" (PDF). Australian Maritime Safety Authority. 20 March 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2015.

- ^ "Search operation for Malaysian airlines aircraft: Update 2" (PDF). Australian Maritime Safety Authority. 18 March 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 March 2014.

- ^ "Search operation for Malaysia Airlines aircraft: Update 4" (PDF). Australian Maritime Safety Authority. 19 March 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2015.

- ^ "Object 1 Possibly Associated with MH370 Search". Department of Defence (Australia). 20 March 2014. Retrieved 21 March 2015 – via Australian Maritime Safety Authority.

- ^ "Object 2 Possibly Associated with MH370 Search". Department of Defence (Australia). 20 March 2014. Retrieved 21 March 2015 – via Australian Maritime Safety Authority.

- ^ a b c d "Flight MH370: Images of ocean debris". BBC News. 28 March 2014. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ^ Hurst, Daniel; Farrell, Paul; Branigan, Tania (20 March 2014). "MH370: two objects spotted in southern Indian Ocean, Australia says". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ a b c Austin, Henry (24 March 2014). "Missing Jet: 'Orange Rectangular Object' Spotted in Sea". NBC News. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- ^ a b "(Flight MH370) Message from Beijing: "Liars"". The Standard. 25 March 2014. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ^ "MH370 passengers' relatives protest in China". Al Jazeera. 25 March 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ Blanchard, Ben; Wee, Sui-Lee (25 March 2014). "China's Xi to send special envoy to Malaysia over missing plane". Reuters. Retrieved 1 April 2014 – via Yahoo! News.

- ^ Hatton, Celia (25 March 2014). "Malaysia Airlines MH370: Relatives in Beijing scuffles". BBC News. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- ^ Donnison, Jon (26 March 2014). "Flight MH370: 122 new objects spotted – Malaysia minister". BBC News. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- ^ Withnall, Adam (26 March 2014). "Missing Malaysia flight MH370: French satellite images show possible 'debris field' of 122 objects in search area". The Independent. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- ^ Niam, Seet Wei (31 March 2014). "MH370: Malaysia Following International Procedures on Information Disclosure". Bernama. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ "Updated statement on Malaysian Airlines Flight MH370 issued 26 March 2014". Air Accidents Investigation Branch. 26 March 2014. Archived from the original on 28 March 2014.

- ^ Adams, Paul; Head, Jonathan (27 March 2014). "Flight MH370: Thai satellite 'shows 300 floating objects'". BBC News. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ Shoichet, Catherine E.; Pearson, Michael; Mullen, Jethro (27 March 2014). "Flight 370 search area shifts after credible lead". CNN. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ^ "International panel to be set up". The Star. 30 March 2014. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ "Air Chief Marshal Angus Houston to lead Joint Agency Coordination Centre". Office of the Prime Minister of Australia. 30 March 2014. Archived from the original on 3 November 2014.

- ^ a b c "Update on MH370 Search". Joint Agency Coordination Centre. 22 May 2014. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ a b Innis, Michelle (6 October 2014). "Rugged Seabed Seen in New Maps Further Complicates Search for Malaysia Airlines Jet". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ a b c Brumfield, Ben; Yan, Holly (1 May 2014). "MH370 report: Mixed messages ate up time before official search initiated". CNN. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ a b "MH370: Inmarsat satellite data revealed to the public". CNN. 27 May 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ Bachman, Justin (1 April 2014). "Missing Jet Alone Will Push Up This Year's Airline Death Toll". Bloomberg. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ "Industry Addressing Aircraft Tracking Options". International Air Transport Association. 3 June 2014. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ a b Childs, Nick (5 April 2014). "Malaysia missing plane search China ship 'picks up signal'". BBC News. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ "Chinese search vessels discovers pulse signal in Indian Ocean". Xinhua News Agency. 5 April 2014. Archived from the original on 5 April 2014. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "Transcript of Press Conference, 9 April 2014". Joint Agency Coordination Centre. 9 April 2014. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- ^ a b Westcott, Richard (7 April 2014). "Malaysia missing plane MH370 search has 'best lead so far'". BBC News. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- ^ "Malaysia Reorganizes Flight 370 Investigation, Appoints Independent Investigator". Frequent Business Traveler. Accura Media Group. 6 April 2014. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ "Missing Malaysia plane: Search 'regains recorder signal'". BBC News. 9 April 2014. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ a b "Malaysia releases preliminary report on MH370". Deutsche Welle. 1 May 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ "Update on search for Malaysian flight MH370 (11 April 2014 pm)". Joint Agency Coordination Centre. 11 April 2014. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- ^ Pearlman, Jonathan (14 April 2014). "Malaysia Airlines MH370: submarine to be deployed as oil slick spotted". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- ^ a b "Update on search for flight MH370". Joint Agency Coordination Centre. 17 April 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ Withnall, Adam. "Malaysia Airlines flight MH370: Analysis of Indian Ocean oil slick shows it is not from missing jet". The Independent. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- ^ a b "Transcript of Press Conference, 14 April 2014". Joint Agency Coordination Centre. 14 April 2014. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ "Missing flight MH370: Robotic submarine to begin search". BBC News. 14 April 2014. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- ^ Swan, Noelle (15 April 2014). "Malaysia Airlines Flight MH370: Robot sub back at work after false start". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ^ Farrel, Paul; Safi, Michael. "Link to MH370 discounted after debris washes up on Western Australia coast". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 April 2014. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ^ "Search continues for Malaysian flight MH370". Joint Agency Coordination Centre. 24 April 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

The Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) has advised that after examining detailed photographs of material washed ashore 10 kilometres east of Augusta, it is satisfied it is not a lead in relation to the search for missing flight MH370.

- ^ Donnison, Jon (28 April 2014). "Missing plane: Search enters 'new phase'". BBC News. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- ^ Cox, Lisa (28 April 2014). "Fruitless search for MH370 will scour larger area of ocean floor, says Tony Abbott". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- ^ "Ocean Shield on route to Fleet Base West". Joint Agency Coordination Centre. 2 May 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ "ADV Ocean Shield Arrives Back in Search Area". Joint Agency Coordination Centre. 14 May 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ "Update on MH370 Search". Joint Agency Coordination Centre. 15 May 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ "Transcript of Press Conference, 5 May 2014". Joint Agency Coordination Centre. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ^ Razak, Najib (13 May 2014). "Malaysia's Lessons From the Vanished Airplane". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- ^ "MH370 Operational Search Update — 05 November 2014". Joint Agency Coordination Centre. 20 March 2015. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- ^ "Malaysia missing MH370 plane: 'Ping area' ruled out". BBC News. 29 May 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ^ a b c "Media Release by The Hon Warren Truss MP, Deputy Prime Minister 26 June 2014". Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development. Retrieved 27 June 2014 – via Joint Agency Coordination Centre.

- ^ a b c d "MH370 search resumes in Indian Ocean". BBC News. 6 October 2014. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ^ a b "Contractor Announced for MH370 Underwater Search". Joint Agency Coordination Centre. 6 August 2014. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- ^ a b "Dutch firm wins $50m contract to search for missing plane MH370". The Guardian. Australian Associated Press. 6 August 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ^ Molko, David; Ahlers, Mike; Marsh, Rene (3 June 2014). "CNN:Is mystery underwater sound the crash of Flight 370?". CNN. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- ^ Ducey, Liam (4 June 2014). "Curtin University researchers find possible acoustic trace of MH370". WAtoday. Fairfax Digital. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ a b "Update on MH370 Search". Joint Agency Coordination Centre. 10 June 2014. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ Fernandez, Celine (12 June 2014). "Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 Families to Get $50,000 Each". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ^ Feast, Lincoln (26 June 2014). "Malaysia jet passengers likely suffocated, Australia says". Reuters. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- ^ Stacey, Daniel; Pasztor, Andy; Winning, David (26 June 2014). "Australian Report Postulates Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 Lost Oxygen". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- ^ "MH370 search unaffected by MH17". The Rakyat Post. Retrieved 21 July 2014.