American McGee's Alice

| American McGee's Alice | |

|---|---|

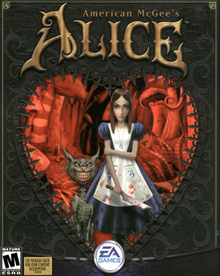

North American cover art | |

| Developer(s) | Rogue Entertainment[a] |

| Publisher(s) | Electronic Arts[b] |

| Director(s) | American McGee |

| Producer(s) | R. J. Berg |

| Designer(s) |

|

| Programmer(s) |

|

| Composer(s) | Chris Vrenna |

| Engine | id Tech 3 |

| Platform(s) | |

| Release | WindowsMac OS |

| Genre(s) | Action-adventure |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

American McGee's Alice is a 2000 third-person action-adventure video game developed by Rogue Entertainment under the direction of designer American McGee and published by Electronic Arts under the EA Games banner. The game was originally released for Windows and Mac OS. Although a planned PlayStation 2 port was cancelled, the game was later released digitally for the PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360, via downloadable content for its sequel.

The game's premise is based on the Lewis Carroll novels Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking-Glass (1871), but presents a gloomy, cruel and violent version of the setting. The game centers on the novels' protagonist Alice, whose family is killed in a house fire years before the story of the game takes place. After several years of treatment in a psychiatric clinic, the emotionally traumatized Alice makes a mental retreat to Wonderland, which has been disfigured by her injured psyche.

American McGee's Alice uses the id Tech 3 game engine, which was previously used in Quake III Arena and redesigned for this game by Ritual Entertainment. The game was met with positive critical reception, with reviewers commending the high artistic and technical quality of the level design, while criticizing the excessive linearity of the gameplay. As of September 2017, American McGee's Alice has sold over 1.5 million copies. A sequel, Alice: Madness Returns, was released in 2011.

Gameplay

[edit]American McGee's Alice is a third-person action game in which the player controls the titular character Alice along a linear route.[5][6] Alice can communicate with non-player characters, fight off enemies and bosses, and solve puzzles. Along with the basic actions of walking and jogging, Alice can jump, cling to ledges, climb and swing on ropes, swim in water, and glide over columns of steam by using her inflated dress as a makeshift parachute. The game can be played at four difficulty levels: "Easy", Medium", "Hard" and "Nightmare". The game's levels feature many platforms and other obstacles not based on artificial intelligence, as well as puzzles that require solving for further passage through the game.

Throughout the game, Alice can obtain up to ten different weapons, known as "toys", for use against enemies. Most toys have two modes of use, which differ in the method and strength of the attack. The first toy acquired by Alice is the Vorpal Blade, which, along with the Croquet Mallet, can be used for basic melee attacks. Toys with longer range include the Ice Wand and an explosive jack-in-the-box. One particular toy, the Jabberwock's Eye Staff, is essential to the narrative and is assembled from pieces scattered throughout the setting. The game's combat system implements automatic target designation: if an enemy character is nearby, the player's weapon sight is automatically fixed upon that enemy. Outside of combat, the sight plays the role of a jump indicator by taking on the shape of two footprints that appear on the surface of any place that Alice would land if she made a jump.

Because the game takes place within Alice's imagination, the health mechanic is represented as "sanity", which is displayed as a red bar on the left-hand side of the screen. The sanity meter decreases when Alice sustains damage from enemy attacks or an environmental hazard. When the sanity meter is depleted, the game prematurely ends, after which it can be continued from where the game was last saved. A magic mechanic is represented as "willpower", and it is displayed as a blue bar on the right-hand side of the screen. Willpower is consumed when almost any toy is used, and a toy will not serve its function when Alice's willpower is too low. Certain amounts of sanity or willpower can be restored by collecting crystals of "meta-essence", the life force of Wonderland. Crystals of "meta-substance", representing the power of imagination, restore sanity and willpower simultaneously. All crystal types can be found scattered across levels and some respawn within certain places. Meta-substance can be obtained after defeating an enemy; the volume of the meta-substance is dependent on the strength of the defeated enemy.

Certain uncommon items can be found throughout the game that enhance Alice's abilities: "Ragebox Elixir" increases the damage dealt by Alice with the Vorpal Blade, the "Darkened Looking Glass" makes Alice invisible to enemies, and "Grasshopper Tea" augments Alice's speed and jumping height. These items change Alice's appearance and their effects are limited to a short period of time, after which Alice returns to her original state.

Plot

[edit]

In 1863, Alice Liddell is awoken from a dream of Wonderland by a house fire. Although she is able to save herself, her parents are killed and she is left with serious burns and psychological damage. Alice is brought to Rutledge Asylum in a state of catatonia, where several years of treatment fail to rouse her from her stupor. When Alice's toy rabbit seems to call to her for help, she mentally retreats to Wonderland, which appears to have been disfigured by her broken mind. Alice meets the Cheshire Cat, who invites her to follow the White Rabbit. She learns from nearby village inhabitants that the Queen of Hearts has put Wonderland in decline and despondency, and that the White Rabbit has promised a champion in Alice. Alice is directed to an old gnome who can aid her pursuit of the White Rabbit by reducing her size. The gnome and Alice infiltrate the Fortress of Doors and enter the school inside, where they create an elixir that shrinks Alice and allows her passage to the Vale of Tears.

After aiding the Mock Turtle in retrieving his stolen shell from the Duchess, Alice catches up to the White Rabbit, who takes her in the direction of the Caterpillar before he is crushed by the normal-sized Hatter's foot. Alice meets with the Caterpillar, who explains to her that Wonderland's current form is the result of Alice's survivor guilt and advises her to slay the Queen of Hearts to restore Wonderland's integrity. Alice returns to normal size after nibbling from a mushroom guarded by the Voracious Centipede. In the center of a plateau, Alice discovers a piece of the Jabberwock's Eye Staff. The voice of an unseen oracle tells Alice that before the Queen of Hearts can be slain, Alice must first eliminate the Queen's sentinel – the Jabberwock, who she must kill to obtain the final piece of the Eye Staff. In her search for the remaining pieces of the Eye Staff, Alice defeats the Red King in the chess-themed Looking-Glass Land, as well as the Hatter's minions Tweedledum and Tweedledee. Alice later finds that the Hatter is conducting cruel experiments on the March Hare and Dormouse, and he is keeping the Gryphon captive. After killing the Hatter, Alice frees the Gryphon, who offers to rally forces against the Queen of Hearts and takes Alice to the Land of Fire and Brimstone, the abode of the Jabberwock. Within the remains of Alice's old home, the Jabberwock wracks Alice with guilt over her parents' deaths and overpowers her in a fight until the Gryphon returns and rescues Alice by depriving the Jabberwock of one of his eyes.

With the Jabberwock's Eye Staff fully assembled, the Gryphon directs Alice to Queensland and takes off with the intention of stopping the Jabberwock himself. On her way to the Queen of Hearts's castle, Alice sees the Gryphon and the Jabberwock engaged in an aerial battle, which ends with the Gryphon mortally wounded. Following Alice's victory against the Jabberwock, the dying Gryphon entrusts Alice with the final battle against the Queen of Hearts. At the entrance to the Queen's Hall, the Cheshire Cat attempts to confess to Alice about the nature of the Queen of Hearts, but he is suddenly executed as he states that "You are two parts of the same..." Alice engages in a fight with a figure puppeteered by the real Queen of Hearts, a giant fleshy tentacled creature who warns Alice that destroying her will destroy them both. Upon Alice's final victory over the Queen of Hearts, Wonderland is restored, and many of the characters who had died in the journey are revived. Her mind repaired, Alice leaves Rutledge Asylum.

Development

[edit]Conception

[edit]After leaving id Software in 1997, creative director American McGee was inspired to design a game that did not involve space marines, guns, aliens and outer space, which were the common themes in the Doom and Quake series.[7] McGee's dark and lustrous image of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland was primarily inspired by the Crystal Method track "Trip Like I Do", in which he heard the word "wonder".[8][9] Following this inspiration, McGee and his creative partner R.J. Berg began sketching a narrative and preliminary designs. McGee's goal was to present what he considered to be a natural extension of the setting and characters of the original Alice novels. Many of the early experiments with evolving the material of the novel – which included manga, futuristic, cartoon and sexual interpretations – strayed from McGee's intended direction. Sketches of Alice, the Cheshire Cat and the Hatter by Terry Smith and Norm Felchle played a decisive role in establishing the game's visual style and served as a foundation for subsequent concept art.[9] McGee sought to omit shortcomings in products that he had previously designed, such as recreating reality instead of creating a fantastic world, reusing traditional weapons, and unremarkable characters.[8] The game had a budget of $4.5 million.[10]

While working on the game's plot, McGee considered several approaches to Alice's return to Wonderland, one of which involved a modern-day Alice murdering her abusive stepfather in reality while journeying through Wonderland, which was rejected by EA. Another approach involved the projection of Alice's parents and acquaintances onto the characters of Wonderland and Alice investigating the cause of her father's death. After discarding this concept as too complicated, McGee ultimately aimed for "the simplest story that told the most".[11][12] Aside from the reappearance of characters and locations mentioned in the novels, no references to the novels' plots are made in the game,[13] as McGee did not intend for the game to be a continuation or competing version of Carroll's work.[14] The development team solely used the original novels as reference material, ignoring film adaptations and other derivative works.[15]

The game's title, which includes McGee's name, was chosen at EA's insistence, primarily for the ease of registering and protecting a new trademark. McGee admitted that he did not support the title, as he opined that it put the rest of the development team in the background.[8][16] American McGee's Alice is McGee's debut work as a lead game designer.[17]

Development and marketing

[edit]EA licensed Ritual Entertainment's Heavy Metal: F.A.K.K.² engine, which is in turn a modified Quake III Arena engine. The most notable changes in the engine include the use of the Tiki model system, which enables the engine to use skeletal animation among other things, the Babble dialog system which enables lip synching of audio with character animations, dynamic music system, scriptable camera, particle system and extended shader support.[18] The changes implemented to the engine for Alice remained minimal however. The game's .bsp files even retain F.A.K.K.²'s headers, albeit sporting a different version number.

An early version of the game featured the ability to summon the Cheshire Cat to aid the player in battle. Though this feature was removed from the final product, beta screenshots of this version do exist online. In the final product, the player can press a button to summon the Cheshire Cat at any time, though he merely provides cryptic advice on the current situation and does nothing to aid Alice if she is being attacked. An Alice port for the then-unreleased PlayStation 2 was also in development but was later cancelled, which caused Rogue Entertainment to shut down, another decision which angered American McGee and resulted him leaving EA in frustration.[9]

The game's box art was altered after release to show Alice holding the Ice Wand instead of the Vorpal Blade and to reduce the skeletal character of the Cheshire Cat's anatomy. EA cited complaints from various consumer groups as its reason for altering the original art, though McGee stated the alteration was made due to internal concerns at EA.[19]

Alice was EA's first M-rated game,[20] a rating which McGee fought to obtain, because he did not want an Alice product to be sold at Christmas time, since parents could be confused, thinking that the game was intended to be a gift for children. However, in a 2009 interview, McGee expressed regret for his decision and said that the violence in the game did not warrant an M-rating; he felt that consumers should buy products responsibly after referring to the recommendations of the ESRB.[21]

Music

[edit]All of the music created for the official American McGee's Alice soundtrack was written and performed by Chris Vrenna with the help of guitarist Mark Blasquez and singer Jessicka.[22] Most of the sounds he used were created using toy instruments and percussion, music boxes (in a short documentary about the making of the game that appeared on TechTV, the music box used appears to be an antique Fisher-Price music box pocket radio), clocks, doors, and sampled female voices were manipulated into nightmarish soundscapes, including instances of them laughing maniacally, screaming, crying, and singing in an eerie, childlike way.

The music lends an eerie and horrifying feeling to the world Alice is in. The Pale Realm theme, as well as the track "I'm Not Edible", features the melody of the chorus of a popular children's song, "My Grandfather's Clock". In addition, there are many instances of the ticking and chiming of clocks being used as a musical accompaniment.

Marilyn Manson was originally involved scoring the music for the game.[23] His composition has been described by American McGee as "very cool" and having "a very beautiful Beatles-in-their-harpsichord-and-Hookah-pipe-days-sound to it." Manson's contributions persisted into the final product, notably the influence of alchemy and the character of the Mad Hatter whose adaptation was somewhat influenced by him; for a time Manson was considered for the voice of the Hatter.[24] Manson has indicated that the same music may be used in his forthcoming film Phantasmagoria: The Visions of Lewis Carroll.

American McGee's Alice Original Music Score was released on October 16, 2001, by Six Degrees Records. It features all twenty original compositions by former Nine Inch Nails live drummer and studio collaborator Chris Vrenna with vocals done by Jessicka Addams of Jack Off Jill and Scarling. It includes a previously unreleased theme as well as a remix of "Flying on the Wings of Steam".

Merchandise

[edit]

Alice produced merchandise until its forthcoming sequel Alice: Madness Returns, this included action figurines, clothing and knife replicas. These pieces have become coveted collectors items due to the low efforts in manufacturing. The soundtrack was released on CD.[22] With pre-ordering the physical copy of the game, you would receive a miniature figure of the Cheshire Cat made of pewter. In 2000, Prima Games published the "American McGee's Alice: Official Strategy Guide".[25]

In 2004, there was a collaboration 7" clear blue LP 'American McGee's Alice Blue Vinyl' from EA and Atari of two sides, Side A: 'Wonderland Woods (Tweaker Remix)' and Side B: 'Take the Pill' from Enter the Matrix composed, produced and remixed by Chris Vrenna. These LP's were limited to 500 copies and signed by McGee and Vrenna.[26]

In 2006, Muckle Mannequins created life-sized statues of Alice and the Cheshire Cat on stands with variants for video game stores for international promotion from its success.[27] For costume ware American McGee's company Mysterious released a replica of the Omega Necklace worn by Alice throughout the game.[28] There was also casual clothing items released such as t-shirts, backpacks, beanies and wallets.

Milo's Workshop completed four editions of releases from 2000 to 2009 of official figurines with rare editions of variants of Alice with the Cheshire Cat, the Mad Hatter, the White Rabbit, TweddleDum and TweedleDee, Card Guards of the Red Queen, the Caterpillar and the Jabberwocky.[29][30] In 2003, Milo's Workshop presented the 20" Cheshire Cat statue with limited 1000 created.[31]

In 2010, for the 10th anniversary, there was an release of the a Vorpal Blade replica by Epic Weapons with a display stand to be sold, you could have also bought and pre-ordered them for San Diego Comic-Con as well as being able to participate in an auction for the first 25 blades.[32][33]

In 2011, Epic Weapons released a packaged deal with the Alice: Madness Returns Vorpal Blade replica. The Vorpal Blade was limited to 1000 replicas.[34]

Reception

[edit]| Aggregator | Score |

|---|---|

| Metacritic | 85/100[35] |

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| AllGame | |

| Computer Gaming World | |

| Edge | 4/10[38] |

| Eurogamer | 8/10[39] |

| Game Informer | 9/10[40] |

| GamePro | |

| GameRevolution | B[42] |

| GameSpot | 7.3/10[6] |

| GameSpy | 93%[43] |

| GameZone | 10/10[44] |

| Hyper | 84/100[45] |

| IGN | 9.4/10[5] |

| Next Generation | |

| PC Gamer (US) | 88%[47] |

| X-Play | |

| The Cincinnati Enquirer |

In the United States, American McGee's Alice sold 360,000 units by August 2006. As of September 2017, the game has sold 1.5 million copies.[50] At the time, this led Edge to declare it the country's 47th-best-selling computer game released since January 2000.[51]

The game was ultimately released on December 5, 2000,[5] receiving praise for its visuals; the graphics were very elaborate for their time. Many levels depict a world of chaos and wonder, some reminiscent of the inside of an asylum or a madhouse, visually linking Wonderland to Alice's reality. The exterior views of Wonderland show the Queen of Hearts' tentacles dipping out of buildings and mountain sides, especially in Queensland. Alice received "favorable" reviews according to the review aggregation website Metacritic.[35] GameSpot said, "While you'll undoubtedly enjoy the imaginative artwork, you might end up disappointed with just how straightforward the underlying game really is."[6]

In her article "Wonderland's become quite strange: From Lewis Carroll's Alice to American McGee's Alice", literary critic Cathlena Martin argues that the game "provides a reinterpreted version of Alice and the whole of wonderland that may have some players questioning which aspects are from Carroll and which are from McGee, thus potentially leading to a rereading of Carroll through the darker lens of McGee's Alice. This reinterpretation of Alice shows the versatility and mutability of the story across time and discourse." Martin also notes that the game is successful largely in part to the narrative structure of Carroll's tales, which are built around games - cards and chess - themselves.[52]

Blake Fischer reviewed the PC version of the game for Next Generation, rating it four stars out of five, and stated that "Alice is an incredibly beautiful and well-designed shooter. If you're looking for more, you may pass, but otherwise it's a game you won't want to miss."[46]

Film adaptation

[edit]Conception and Wes Craven

[edit]A film adaptation of American McGee's Alice was planned prior to the game's release. Scott Faye, a spokesman for Dimension Films and an old acquaintance of McGee, visited EA to negotiate an adaptation of an EA product. Faye and other Dimension Films representatives were shown gameplay footage of Alice and were impressed by its visuals. Later, Miramax head Bob Weinstein was shown the game's trailer, after which he immediately (and without waiting for the opinion of the board of directors) supported the production of a film adaptation.[53] On July 5, 2000, FGN Online published an exclusive piece claiming that EA had signed an agreement with Miramax to create a film based on the game. According to the publisher's source, American McGee would be involved in the film's production, potentially as a creative director or co-producer.[54]

On December 7, 2000, McGee formally announced the film adaptation, which had been entrusted with Collision Entertainment, a subsidiary of Dimension Films, after ten months of negotiations.[53][55][56] Wes Craven and John August were attached as director and screenwriter, with McGee co-producing the film alongside Collision Entertainment, and Abandon Entertainment acting as international distributor.[53][57] No actors had yet been signed on, but Natalie Portman was rumored to have expressed interest.[53] Milla Jovovich and Christina Ricci were also rumored to be attached.[58] In September 2001, August explained that he had turned in a script treatment for Alice and was not attached to develop fuller drafts for the film adaptation.[59]

In December 2001, Craven announced that the film would be a computer-animated feature with a tentative 2003 release date.[60][61] In February 2002, Dimension Films signed brother screenwriters Jon and Erich Hoeber to write a new screenplay for Alice.[62] In July 2003, the brothers announced that they had completed the script for the film adaptation.[63] On March 4, 2004, McGee reported that the project had moved from Dimension Films to 20th Century Fox.[64]

Marcus Nispel

[edit]On June 21, 2005, The Hollywood Reporter reported that Universal Pictures had acquired the film and signed Sarah Michelle Gellar on for the lead role, with Marcus Nispel attached to direct and the Hoeber brothers still attached to write.[65] On February 8, 2006, Scott Faye, who had become a producer of the project, announced that filming would begin in the summer of 2006, with a budget of $40 to $50 million and a tentative 2007 release date.[66] By 2008, the project was in turnaround, and Nispel and Gellar's involvement had ceased. Rumors circulated of Jane March being cast as the Queen of Hearts, which Faye denied.[67]

Short films

[edit]In June 2013, American McGee was given the opportunity to buy back the film rights which were originally sold several years prior. Through Kickstarter, McGee managed to fund the cost of the film rights ($100,000) and another $100,000 for the production of the shorts. In August, the project was successfully funded with an extra $50,000 (used to fund the voice acting of Susie Brann and Roger L. Jackson).[68][69][70]

With the success of earning the funds to produce Alice: Otherlands, McGee stated his desire to continue to work on the possibility of adapting the series into a feature film on Kickstarter.[68][71] On February 17, 2014, McGee announced that he and his team have secured a British screenwriter to write the film's script.[72] On April 16, 2014, he assured fans that the film is still in production and is currently working with a producer in Hollywood who they have licensed the rights from, but has run into a few difficulties along the way.[73]

On July 10, 2014, McGee informed fans that the progress on the feature film has come to a temporary halt. McGee stated that he had secured the rights only to develop the feature film's story and production and needed to acquire the film rights completely before proceeding further. He was speaking with potential investors and financiers to gather the $400,000 (~$502,755 in 2023) required[74] but on January 8, 2015, McGee stated that negotiations for the feature film had gone on a hiatus.[75]

Television adaptation

[edit]On January 31, 2022, it was announced that Radar Pictures – in partnership with Abandon Entertainment – was developing a television adaptation of American McGee's Alice written and co-produced by David Hayter. No broadcaster or streaming platform has yet acquired the series.[76]

Sequel

[edit]As the plans for the movie adaptation of American McGee's Alice started to take longer and longer, in 2007 interest at Electronic Arts rose in a remake of the game and work was started on a sequel.[77] On February 19, 2009, EA CEO John Riccitiello announced at D.I.C.E. 2009 that a new installment to the series is in the works for Xbox 360, PlayStation 3, and PC.[78][79]

It was developed by Spicy Horse, who worked on American McGee's Grimm.[80][81][82] Two pieces of concept art were released, depicting Alice and large allied birds fighting an oversized, semi-mechanized snail and its children on top of a lighthouse,[83] and Alice swimming in a pond, with the Cheshire Cat's face in the background.[84]

In November 2009, a fan-made video based on the Alice 2 announcement was mistaken by gaming websites as a teaser trailer for the game. In it, Alice is in therapy after a relapse nine months after the events of the first game, and she appears to hallucinate an image of the Cheshire Cat in place of her doctor.[85]

On June 15, 2010, EA filed a trademark on the name Alice: Madness Returns, the suspected sequel to American McGee's Alice.[86] While the sequel was formally announced via press release on February 19, 2009,[81] the sequel's title was confirmed during the EA Studio Showcase the following day.

The game was released on June 14, 2011, in North America, June 16, 2011, in Europe, June 17, 2011, in the United Kingdom and July 21, 2011, in Japan[87] under the title Alice: Madness Returns for PC, Mac, Xbox 360, and PlayStation 3. The Xbox 360 and PlayStation 3 versions came with a redemption code that gave the player a free download of American McGee's Alice. This version is available through backward compatibility on Xbox One and Xbox Series X/S, and is part of the EA Play service on these platforms. It is found under the DLC for Madness Returns.

See also

[edit]- Clive Barker's Undying, another auteur-branded PC horror game by EA Games released around the same time

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Alice Gold". GameSpot. Retrieved March 28, 2023.

- ^ "Contributor Missing Headline". Bloomberg. December 5, 2000. Retrieved March 28, 2023.

- ^ "Aspyr: Inside Aspyr". June 20, 2003. Archived from the original on June 20, 2003. Retrieved March 28, 2023.

- ^ a b "Aspyr ships American McGee's Alice for Mac". Macworld. July 12, 2001. Retrieved January 7, 2022.

- ^ a b c Lopez, Vincent (December 5, 2000). "American McGee's Alice review". IGN. Snowball.com. Archived from the original on January 24, 2001. Retrieved May 6, 2014.

- ^ a b c Wolpaw, Erik (December 8, 2000). "PC Reviews: American McGee's Alice Review". GameSpot. Ziff Davis. Archived from the original on February 4, 2001. Retrieved May 6, 2014.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Laporte, Leo (February 21, 2001). "Leo's Interview with American McGee". The Screen Savers. TechTV – via YouTube.

- ^ a b c Callaham, John (August 9, 2000). "American McGee Interview". Stomped. Archived from the original on August 15, 2000.

- ^ a b c McGee, American (2011). The Art of Alice: Madness Returns. Milwaukee, OR: Dark Horse Comics. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-1-59582-697-8.

- ^ Gelmis, Joseph (December 27, 2000). "Where Fantasy Meets Reality". Newsday. pp. 128–129. Retrieved January 23, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Miller, Jennifer; Fryman, Avi (December 15, 2000). "An Interview with American McGee, Part II". Happy Puppy. Archived from the original on January 24, 2001.

- ^ McLean–Foreman, John (July 25, 2001). "Interview with American McGee". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on November 10, 2011.

- ^ Beal, Vangie (October 17, 2000). "McGee's Alice: Character Profile". GameGirlz. Archived from the original on March 2, 2001.

- ^ "American McGee's Alice Interview". IGN. October 9, 2000. Archived from the original on August 13, 2007.

- ^ "INTERVIEW: American McGee". GameLoft. April 5, 2001. Archived from the original on April 5, 2001.

- ^ Sluganski, Randy (May 1, 2001). "Cleaning Up After the White Rabbit: An Intimate Conversation with American McGee". JustAdventure. Archived from the original on May 1, 2001.

- ^ Fahey, Rob (April 17, 2001). "REVIEW: American McGee's Alice". GameLoft. Archived from the original on April 17, 2001.

- ^ "UberTools for Quake III v4.0". ritual.com. Ritual Entertainment. Archived from the original on June 23, 2007. Retrieved August 11, 2009.

- ^ Alice and moral panics? Archived March 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Chris Kohler (July 26, 2010). "Q&A: American McGee Returns to Alice's Nightmare Wonderland". Wired. Archived from the original on July 28, 2010. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- ^ Halpin, Spencer. "Spencer Halpin's Moral Kombat". Spencer Halpin's Moral Kombat. Cinetic Rights Management. Retrieved August 18, 2015.

- ^ a b Chris Vrenna American McGees Alice MP3Download

- ^ "Dramatic New Scenes for Celebritarian Needs". MansonUSA. November 3, 2005. Archived from the original on April 27, 2006. Retrieved July 2, 2024.

- ^ "Manson on American McGee's Alice". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved August 19, 2007.

- ^ "American McGee's Alice | Strategy Guides". VGCollect.com. Archived from the original on August 20, 2024. Retrieved August 20, 2024.

- ^ "Chris Vrenna & American McGee, signed & limited Vinyl - auction details". popsike.com. Archived from the original on August 19, 2024. Retrieved August 19, 2024.

- ^ "American McGee's Alice | Lifesize Heroes". www.lifesize-heroes.com. Archived from the original on August 19, 2024. Retrieved August 18, 2024.

- ^ "Plushie Dreadfuls Official". Mysterious. Archived from the original on August 18, 2024. Retrieved August 19, 2024.

- ^ "American McGee Toys, Action Figures, and Collectibles". September 1, 2013. Archived from the original on September 1, 2013. Retrieved August 19, 2024.

- ^ Saylor, Jeff (February 1, 2022). "AMERICAN MCGEE'S ALICE In Development as TV Series". Figures.com. Archived from the original on February 1, 2022. Retrieved August 18, 2024.

- ^ "Cheshire Cat 20 inch Statue American McGee Alice Limited Edition". Worthpoint. Archived from the original on August 19, 2024. Retrieved August 19, 2024.

- ^ "Vorpal Blade snicker-snacks into auction". Gaming Nexus. Archived from the original on August 19, 2024. Retrieved August 20, 2024.

- ^ Fahey, Mike (July 13, 2010). "American McGee's Alice Vorpal Blade Goes Snicker-Snack For Real". Kotaku. Archived from the original on February 12, 2023. Retrieved August 19, 2024.

- ^ "American McGee's Alice Vorpal Blade, epicweapons.com". September 4, 2011. Archived from the original on September 4, 2011. Retrieved August 20, 2024.

- ^ a b "American McGee's Alice for PC". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on October 9, 2010.

- ^ Denenberg, Darren. "American McGee's Alice (PC) - Review". AllGame. Archived from the original on November 13, 2014. Retrieved July 1, 2017.

- ^ Ardai, Charles (March 2001). "Alice's Bad Trip (American McGee's Alice Review)" (PDF). Computer Gaming World. No. 200. pp. 102–03. Retrieved July 2, 2017.

- ^ Edge staff (January 2001). "American McGee's Alice". Edge. No. 93.

- ^ Carter, Ben (January 6, 2001). "Alice (PC)". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on January 24, 2001. Retrieved May 6, 2014.

- ^ Brogger, Kristian (February 2001). "American McGee's Alice". Game Informer. No. 94. Archived from the original on June 4, 2009. Retrieved May 6, 2014.

- ^ Molloy, Sean (December 5, 2000). "American McGee's Alice Review for PC on GamePro.com". GamePro. Archived from the original on February 7, 2005. Retrieved May 6, 2014.

- ^ The Mock Dodgson (December 2000). "Alice Review". Game Revolution. Archived from the original on May 6, 2014. Retrieved July 1, 2017.

- ^ Salgado, Carlos "dr.angryman" (December 19, 2000). "American McGee's Alice". GameSpy. Archived from the original on December 8, 2005. Retrieved May 6, 2014.

- ^ The Badger (December 10, 2000). "American McGee's Alice - PC - Review". GameZone. Archived from the original on January 20, 2009. Retrieved May 6, 2014.

- ^ Shea, Cam (March 2001). "American McGee's Alice". Hyper. No. 89. pp. 54–55.

- ^ a b Fischer, Blake (March 2001). "Finals". Next Generation. Vol. 4, no. 3. Imagine Media. p. 90.

- ^ Osborn, Chuck (February 2001). "American McGee's Alice". PC Gamer. p. 50. Archived from the original on October 28, 2004. Retrieved May 6, 2014.

- ^ Roberts, Josh (January 25, 2001). "Alice Review". X-Play. Archived from the original on January 27, 2001. Retrieved May 6, 2014.

- ^ Saltzman, Marc (January 24, 2001). "Alice's wonderland game disturbing, yet oddly fun". The Cincinnati Enquirer. Archived from the original on April 19, 2001. Retrieved May 6, 2014.

- ^ Joseph, Remington (September 3, 2017). "American McGee Working On Alice 3 Proposal". CGMagazine. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ Edge Staff (August 25, 2006). "The Top 100 PC Games of the 21st Century". Edge. Archived from the original on October 17, 2012.

- ^ Martin, Cathlena (2010). "10". Beyond Adaptation: Essays on Radical Transformations of Original Works. Jefferson: McFarland and Co. pp. 136–137.

- ^ a b c d Morris, Chris (January 24, 2001). "American McGee Interview". Well Rounded Entertainment. Archived from the original on July 8, 2001.

- ^ Ogden, Gavin (July 5, 2000). "Alice Goes to Hollywood". FGN Online. Archived from the original on August 17, 2000.

- ^ Linder, Brian (December 7, 2000). "Wes Craven to Dark Wonderland". IGN. Archived from the original on October 26, 2007. Retrieved February 13, 2007.

- ^ "INTERVIEW: American McGee (Part 2)". GameLoft. April 14, 2001. Archived from the original on April 14, 2001.

- ^ Gaudiosi, John (August 9, 2001). "Payne game screen-bound". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on August 14, 2001.

- ^ "Gellar is Alice". IGN. June 21, 2005. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- ^ Linder, Brian (September 25, 2001). "August Talks Alice". IGN. Archived from the original on February 6, 2007. Retrieved February 13, 2007.

- ^ "Craven Develops New Alice". Sci-Fi Wire. December 26, 2001. Archived from the original on February 14, 2002.

- ^ Bing, Jonathan (December 31, 2001). "Craven preps Alice as computer-animated feature". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on January 3, 2002.

- ^ Linder, Brian (February 11, 2002). "Scribes Pegged for Alice Game-to-Film Adaptation". IGN. Retrieved February 13, 2007.

- ^ Linder, Brian (July 29, 2003). "Games-to-Film Update: Alice, Oz". IGN. Archived from the original on December 7, 2006. Retrieved February 13, 2007.

- ^ Linder, Brian (March 4, 2004). "McGee Movie Update". IGN. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- ^ Kit, Borys; Gaudiosi, John (June 21, 2005). "Universal to put Gellar in Wonderland". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on June 30, 2009.

- ^ Remo, Chris (February 8, 2006). "Alice and Max on Their Way to the Big Screen". Shacknews. Archived from the original on May 25, 2013.

- ^ McGee, American (June 20, 2008). "American McGee's Alice – Film Interview". Archived from the original on March 9, 2012.

- ^ a b "Alice: Otherlands".

- ^ "They're Back..."

- ^ "Stretch Goooooal!".

- ^ "A Night at the Opera".

- ^ "Progress and Possibilities".

- ^ "Eyeballs, Tentacles, and Monsters".

- ^ "Noble Pursuits".

- ^ "Happy New Year 2015!".

- ^ Vlessing, Etan (January 31, 2022). "X-Men Scribe David Hayter Boards TV Adaptation of EA's American McGee's Alice Game (Exclusive)". Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ Müller, Martijn. "Remake American McGee's Alice in de maak" (in Dutch). NG-Gamer. Archived from the original on February 8, 2008. Retrieved November 1, 2007.

- ^ Crecente, Brian (February 19, 2009). "EA Announces New American McGee's Alice Title". Kotaku.com. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ^ "The Return of American McGee's Alice Set For PC, Consoles". Kotaku. February 19, 2009. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ^ "DICE 2009: EA announces American McGee's Alice 2". Joystiq. February 19, 2009. Archived from the original on February 21, 2009. Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- ^ a b "EA and Spicy Horse Return to Wonderland for All-New Alice Title". ea.com. February 19, 2009. Archived from the original on February 27, 2009. Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- ^ Chester, Nick (February 19, 2009). "Sequel to American McGee's Alice coming to PC, consoles in 2009". Destructoid. Archived from the original on February 26, 2009. Retrieved February 19, 2009.

- ^ "The Return of Alice". americanmcgee.com. February 20, 2009. Archived from the original on February 21, 2009. Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- ^ "Hiring – Three for Art". americanmcgee.com. May 4, 2009. Archived from the original on May 31, 2009. Retrieved June 28, 2009.

- ^ "Return of Alice (Video Madness)". November 4, 2009. Archived from the original on November 15, 2009.

- ^ "Latest Status Info". tarr.uspto.gov. June 20, 2010. Archived from the original on June 22, 2010. Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- ^ "MUlti アリス マッドネス リターンズ JPPV". YouTube. May 15, 2011.

External links

[edit]- American McGee's Alice at IMDb

- American McGee's Alice at MobyGames

- "Down the Rabbit Hole". Archived from the original on April 20, 2009. Retrieved January 21, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "Concept art". Archived from the original on August 2, 2008. Retrieved January 6, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- 2000 video games

- 3D platformers

- Action-adventure games

- Aspyr games

- Body horror video games

- Cancelled PlayStation 2 games

- Classic Mac OS games

- Cultural depictions of Alice Liddell

- Dark fantasy video games

- Electronic Arts games

- Fiction set in 1863

- Fiction set in 1873

- Fiction set in 1874

- Game Developers Choice Award winners

- Hack and slash games

- Id Tech 3 games

- MacOS games

- PlayStation 3 games

- PlayStation Network games

- Single-player video games

- Third-person shooters

- Video games about mental health

- Video games about size change

- Video games based on Alice in Wonderland

- Video games developed in the United States

- Video games set in psychiatric hospitals

- Video games set in the 1860s

- Video games set in the 1870s

- Video games set in the Victorian era

- Westlake Interactive games

- Windows games

- Xbox 360 games