Animatronics

Animatronics refers to the use of robotic devices to emulate a human or an animal, or bring lifelike characteristics to an otherwise inanimate object.[1][2] A robot designed to be a convincing imitation of a human is more specifically labeled as an android.[3][4][5] Modern animatronics have found widespread applications in movie special effects and theme parks and have, since their inception, been primarily used as a spectacle of amusement.

Animatronics is a multi-disciplinary field which integrates anatomy, robots, mechatronics, and puppetry resulting in lifelike animation.[6][7] Animatronic figures are often powered by pneumatics, hydraulics, and/or by electrical means, and can be implemented using both computer control and human control, including teleoperation. Motion actuators are often used to imitate muscle movements and create realistic motions in limbs. Figures are covered with body shells and flexible skins made of hard and soft plastic materials and finished with details like colors, hair and feathers and other components to make the figure more realistic.

Etymology

Animatronics is portmanteau of animate and electronics [8]

The term audio-animatronics was coined by Walt Disney in 1961 when he started developing animatronics for entertainment and film. Audio-Animatronics does not differentiate between animatronics and androids.

Autonomatronics was also defined by Walt Disney Imagineers, to describe a more advanced audio-animatronic technology featuring cameras and complex sensors to process information around the character's environment and respond to that stimulus.[9]

Timeline

- 1220 – 1240: The Portfolio of Villard de Honnecourt depicts an early escapement mechanism in a drawing titled How to make an angel keep pointing his finger toward the Sun and an automaton of a bird, with jointed wings.[10]

- 1515: Leonardo da Vinci designed and built the Automata Lion.[11]

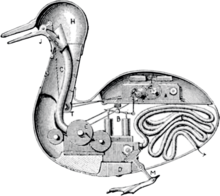

- 1738: The construction of automata begins in Grenoble, France by Jacques de Vaucanson. First, a flute player that could play twelve songs - The Flute Player, followed by a character playing a flute and drum or tambourine - The Tambourine Player, and concluding with a moving / quacking / flapping / eating duck - The Digesting Duck.[12]

- 1770: Pierre Jaquet-Droz and his son Henri-Louis Jaquet-Droz, both Swiss watchmakers, start making automata for European royalty. Once completed, they had created three dolls. One doll was able to write, the other play music and the third doll could draw pictures.[13]

- 1801: Joseph Jacquard builds a loom that is controlled autonomously with punched cards.

- 1939: Sparko, The Robot Dog, pet of Elektro, performs in front of the public but Sparko, unlike many depictions of robots in that time, represented a living animal, thus becoming the very first modern day animatronic character,[14] along with an unnamed horse which was reported to gallop realistically. The animatronic galloping horse was also on display at the 1939 World's Fair, in a different exhibit than Sparko's.[15], 1939 New York World's Fair

- 1961: Heinrich Ernst develops the MH-1, a computer-operated mechanical hand.[16]

- 1961: Walt Disney coins the term audio-animatronics and begins developing modern animatronic technology.[17]

- 1963: The first animatronics, called Audio-Animatronics, created by Disney were the Enchanted Tiki Birds., Disneyland

- 1964: In the film Mary Poppins, animatronic birds are the first animatronics to be featured in a motion picture.

- 1965: The first animatronics figure of a person is created by Disney and is Abraham Lincoln.[17]

- 1968: The first animatronic character at a restaurant is created. Goes by the name Golden Mario and was built by Team Built in 1968.[17]

- 1977: Chuck E. Cheese's (then known as Pizza Time Theatre) opens its doors, as the first restaurant with animatronics as an attraction.

- 1980: ShowBiz Pizza Place opens with the Rock-afire Explosion

- 1982: Ben Franklin is the first animatronic figure to walk up a set of stairs.[18]

- 1989: The first A-100 animatronic is developed for The Great Movie Ride attraction at the Disney-MGM Studios' to represent The Wicked Witch of the West.

- 1993: The largest animatronic figure ever built is the T. rex for the movie, Jurassic Park.

- 1998: Tiger Electronics begins selling Furby, an animatronic pet with over 800 English phrases or Furbish and the ability to react to its environment., Vernon Hills, Illinois

- May 11, 1999: Sony releases the AIBO animatronics pet., Tokyo, Japan

- 2008: Mr. Potato Head at the Toy Story exhibit features lips with superior range of movement to any other animatronic figure previously.[19], Disney's Hollywood Studios

- October 31, 2008 – July 1, 2009: The Abraham Lincoln animatronic character is upgraded to incorporate autonomatronic technology.[17], The Hall of Presidents

- September 28, 2009: Disney develops Otto, the first interactive figure that can hear, see and sense actions in the room.[17], D23 Expo

History

Origins

The 3rd-century BC text of the Liezi describes an encounter between King Mu of Zhou and an 'artificer' known as Yan Shi, who presented the king with a life-size automaton. The 'figure' was described as able to walk, pose and sing, and when dismantled was observed to consist of anatomically accurate organs.[20]

The 5th-century BC Mohist philosopher Mozi and his contemporary Lu Ban are attributed with the invention of artificial wooden birds (ma yuan) that could successfully fly in the Han Fei Zi[21] and in 1066, the Chinese inventor Su Song built a water clock in the form of a tower which featured mechanical figurines which chimed the hours.

In 1515, Leonardo da Vinci designed and built the Automata Lion, one of the earliest described animatrons. The mechanical lion was presented by Giuliano de’ Medici of Florence to Francois I, King of France as a symbol of an alliance between France and Florence.[22] The Automata Lion was rebuilt in 2009 according to contemporary descriptions and da Vinci's own drawings of the mechanism.[22] Prior to this, da Vinci had designed and exhibited a mechanical knight at a celebration hosted by Ludovico Sforza at the court of Milan in 1495.[23] The 'robot' was capable of standing, sitting, opening its visor and moving its arms. The drawings were rediscovered in the 1950s and a functional replica was later built.[23]

Early implementations

Clocks

While functional, early clocks were also designed as novelties and spectacles which integrated features of early animatronics.

Approximately 1220–1230, Villard de Honnecourt wrote The Portfolio of Villard de Honnecourt which depicts an early escapement mechanism in a drawing titled How to make an angel keep pointing his finger toward the Sun and an automaton of a bird, with jointed wings which led to their design implementation in clocks. Because of their size and complexity, the majority of these clocks were built as public spectacles in the town centre. One of the earliest of these large clocks was the Strasbourg Clock, built in the fourteenth century which takes up the entire side of a cathedral wall. It contained an astronomical calendar, automata depicting animals, saints and the life of Christ. The clock still functions to this day but has undergone several restorations since its initial construction. The Prague astronomical clock was built in 1410, animated figures were added from the 17th century onwards.[24]

The first description of a modern cuckoo clock was by the Augsburg nobleman Philipp Hainhofer in 1629.[25] The clock belonged to Prince Elector August von Sachsen. By 1650, the workings of mechanical cuckoos were understood and were widely disseminated in Athanasius Kircher's handbook on music, Musurgia Universalis. In what is the first documented description of how a mechanical cuckoo works, a mechanical organ with several automated figures is described.[26]

In 18th-century Germany, clockmakers began making cuckoo clocks for sale.[24] Clock shops selling cuckoo clocks became commonplace in the Black Forest region by the middle of the 18th century.[27]

Attractions

A banquet in Camilla of Aragon's honor in Italy, 1475, featured a lifelike automated camel.[28] The spectacle was a part of a larger parade which continued over days.

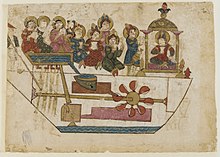

In 1454, Duke Philip created an entertainment show named The extravagant Feast of the Pheasant, which was intended to influence the Duke's peers to participate in a crusade against the Ottomans but ended up being a grand display of automata, giants, and dwarves.[29]

Giovanni Fontana, a Paduan engineer in 1420, developed Bellicorum instrumentorum liber[a] which includes a puppet of a camelid driven by a clothed primate twice the height of a human being and an automaton of Mary Magdalene.[31]

Implementations

Modern attractions

The earliest modern animatronics can actually be found in old robots. While some of these robots were, in fact, animatronics, at the time they were thought of simply as robots because the term animatronics had yet to become popularized.

The first animatronics characters to be displayed to the public were a dog and a horse. Each were the attraction at two separate spectacles during the 1939 New York World's Fair. Sparko, The Robot Dog, pet of Elektro the Robot, performs in front of the public at the 1939 New York World's Fair but Sparko is not like normal robots. Sparko represents a living animal, thus becoming the very first modern day animatronic character,[14] along with an unnamed horse which was reported to gallop realistically. The animatronic galloping horse was also on display at the 1939 World's Fair, in a different exhibit than Sparko's.[15]

Walt Disney is often credited for popularizing animatronics for entertainment after he bought an animatronic bird while he was vacationing, although it is disputed whether it was in New Orleans[32] or Europe.[33] Disney's vision for audio-animatronics was primarily focused on patriotic displays rather than amusements.[34]

In 1951, two years after Walt Disney discovered animatronics, he commissioned machinist Roger Broggie and sculptor Wathel Rogers to lead a team tasked with creating a 9" tall figure that could move and talk simulating dance routines performed by actor Buddy Ebsen. The project was titled 'Project Little Man' but was never finished. A year later, Walt Disney Imagineering was created.[35]

After "Project Little Man", the Imagineering team at Disney's first project was a "Chinese Head" which was on display in the lobby of their office. Customers could ask the head questions and it would reply with words of wisdom. The eyes blinked and its mouth opened and closed.[35]

The Walt Disney Production company started using animatronics in 1955 for Disneyland's ride, the Jungle Cruise,[36] and later for its attraction Walt Disney's Enchanted Tiki Room which featured animatronic Enchanted Tiki Birds.

The first fully completed human audio-animatronic figure was Abraham Lincoln, created by Walt Disney in 1964 for the 1964 World's Fair in the New York. In 1965, Disney upgraded the figure and coined it as the Lincoln Mark II, which appeared at the Opera House at Disneyland Resort in California.[34] For three months, the original Lincoln performed in New York, while the Lincoln Mark II played 5 performances per hour at Disneyland. Body language and facial motions were matched to perfection with the recorded speech. Actor Royal Dano voiced the animatronics version of Abraham Lincoln.[34]

Lucky the Dinosaur is an approximately 8-foot-tall (2.4 m) green Segnosaurus which pulls a flower-covered cart and is led by "Chandler the Dinosaur Handler". Lucky is notable in that he was the first free-roving audio-animatronic figure ever created by Disney's Imagineers.[37] The flower cart he pulls conceals the computer and power source.[38]

The Muppet Mobile Lab is a free-roving, audio-animatronic entertainment attraction designed by Walt Disney Imagineering. Two Muppet characters, Dr. Bunsen Honeydew and his assistant, Beaker, pilot the vehicle through the park, interacting with guests and deploying special effects such as foggers, flashing lights, moving signs, confetti cannons and spray jets. It is currently deployed at Hong Kong Disneyland in Hong Kong.

A Laffing Sal is one of the several automated characters that were used to attract carnival and amusement park patrons to funhouses and dark rides throughout the United States.[39] Its movements were accompanied by a raucous laugh that sometimes frightened small children and annoyed adults.[40] The Rock-afire Explosion in an animatronic band that played in Showbiz Pizza Place from 1980 to 1992.

Film and television

The film industry has been a driving force revolutionizing the technology used to develop animatronics.[41]

Animatronics are used in situations where a creature does not exist, the action is too risky or costly to use real actors or animals, or the action could never be obtained with a living person or animal. Its main advantage over CGI and stop motion is that the simulated creature has a physical presence moving in front of the camera in real time. The technology behind animatronics has become more advanced and sophisticated over the years, making the puppets even more lifelike.

Animatronics were first introduced by Disney in the 1964 film Mary Poppins which featured an animatronic bird. Since then, animatronics have been used extensively in such movies as Jaws, and E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, which relied heavily on animatronics.[24]

Directors such as Steven Spielberg and Jim Henson have been pioneers in using animatronics in the film industry.

The 1993 film Jurassic Park used a combination of computer-generated imagery in conjunction with life-sized animatronic dinosaurs built by Stan Winston and his team. Winston's animatronic "T. rex" stood almost 20 feet (6.1 m),[42] 40 feet (12 m) in length[43] and even the largest animatronics weighing 9,000 pounds (4,100 kg) were able to perfectly recreate the appearance and natural movement on screen of a full-sized tyrannosaurus rex.[44]

Jack Horner called it "the closest I've ever been to a live dinosaur".[43] Critics referred to Spielberg's dinosaurs as breathtakingly — and terrifyingly — realistic.[45][46]

The 1999 BBC miniseries Walking with Dinosaurs was produced using a combination of about 80% CGI and 20% animatronic models.[47] The quality of computer imagery of the day was good, but animatronics were still better at distance shots, as well as closeups of the dinosaurs.[47] Animatronics for the series were designed by British animatronics firm Crawley Creatures.[47] The show was followed up in 2007 with a live adaptation of the series, Walking with Dinosaurs: The Arena Spectacular.

Geoff Peterson is an animatronic human skeleton that serves as the sidekick on the late-night talk show The Late Late Show with Craig Ferguson. Often referred to as a "robot skeleton", Peterson is a radio-controlled animatronic robot puppet designed and built by Grant Imahara of MythBusters.[48]

Advertising

The British advertisement campaign for Cadbury Schweppes titled Gorilla featured an actor inside a gorilla suit with an animatronically animated face.

The Slowskys was an advertising campaign for Comcast Cable's Xfinity broadband Internet service. The ad features two animatronic turtles, and it won the gold Effie Award in 2007.[49]

Toys

Some examples of animatronic toys include Teddy Ruxpin, Big Mouth Billy Bass, Kota the triceratops, Pleo, WowWee Alive Chimpanzee, Microsoft Actimates, and Furby.

Video Games

Animatronics are the main antagonists in the popular horror video game Five Nights at Freddy's.

Design

An animatronics character is built around an internal supporting frame, usually made of steel. Attached to these "bones" are the "muscles" which can be manufactured using elastic netting composed of styrene beads.[50] The frame provides the support for the electronics and mechanical components, as well as providing the shape for the outer skin.[51]

The "skin" of the figure is most often made of foam rubber, silicone or urethane poured into moulds and allowed to cure. To provide further strength a piece of fabric is cut to size and embedded in the foam rubber after it is poured into the mould. Once the mould has fully cured, each piece is separated and attached to the exterior of the figure providing the appearance and texture similar to that of "skin".[52]

Structure

An animatronics character is typically designed to be as realistic as possible and thus, is built similarly to how it would be in real life. The framework of the figure is like the "skeleton". Joints, motors, and actuators act as the "muscles". Connecting all the electrical components together are wires, such as the "nervous system" of a real animal or person.[53]

Frame or skeleton

Steel, aluminum, plastic, and wood are all commonly used in building animatronics but each has its best purpose. The relative strength, as well as the weight of the material itself, should be considered when determining the most appropriate material to use. The cost of the material may also be a concern.[53]

Exterior or skin

Several materials are commonly used in the fabrication of an animatronics figure's exterior. Dependent on the particular circumstances, the best material will be used to produce the most lifelike form.

For example, "eyes" and "teeth" are commonly made completely out of acrylic.[54]

Latex

White latex is commonly used as a general material because it has a high level of elasticity. It is also pre-vulcanized, making it easy and fast to apply.[55] Latex is produced in several grades. Grade 74 is a popular form of latex that dries rapidly and can be applied very thick, making it ideal for developing molds.[56]

Foam latex is a lightweight, soft form of latex which is used in masks and facial prosthetics to change a person's outward appearance, and in animatronics to create a realistic "skin".[56] The Wizard of Oz was one of the first films to make extensive use of foam latex prosthetics in the 1930s.[57]

Silicone

Disney has a research team devoted to improving and developing better methods of creating more lifelike animatronics exteriors with silicone.[58]

RTV silicone (room temperature vulcanization silicone) is used primarily as a molding material as it is very easy to use but is relatively expensive. Few other materials stick to it, making molds easy to separate.[59][60]

Bubbles are removed from silicone by pouring the liquid material in a thin stream or processing in a vacuum chamber prior to use. Fumed silica is used as a bulking agent for thicker coatings of the material.[61]

Polyurethane

Polyurethane rubber is a more cost effective material to use in place of silicone. Polyurethane comes in various levels of hardness which are measured on the Shore scale. Rigid polyurethane foam is used in prototyping because it can be milled and shaped in high density. Flexible polyurethane foam is often used in the actual building of the final animatronic figure because it is flexible and bonds well with latex.[56]

Plaster

As a commonplace construction and home decorating material, plaster is widely available. Its rigidity limits its use in moulds, and plaster moulds are unsuitable when undercuts are present. This may make plaster far more difficult to use than softer materials like latex or silicone.[60]

Movement

Pneumatic actuators can be used for small animatronics but are not powerful enough for large designs and must be supplemented with hydraulics. To create more realistic movement in large figures, an analog system is generally used to give the figures a full range of fluid motion rather than simple two position movements.[62]

Emotion modeling

Mimicking the often subtle displays of humans and other living creatures, and the associated movement is a challenging task when developing animatronics. One of the most common emotional models is the Facial Action Coding System (FACS) developed by Ekman and Friesen.[63] FACS defines that through facial expression, humans can recognize 6 basic emotions: anger, disgust, fear, joy, sadness, and surprise. Another theory is that of Ortony, Clore, and Collins, or the OCC model[64] which defines 22 different emotional categories.[65]

Training and education

Animatronics has been developed as a career which combines the disciplines of mechanical engineering, casting/sculpting, control technologies, electrical/electronic systems, radio control and airbrushing.

Some colleges and universities do offer degree programs in animatronics. Individuals interested in animatronics typically earn a degree in robotics which closely relate to the specializations needed in animatronics engineering.[66]

Students achieving a bachelor's degree in robotics commonly complete courses in:

- Mechanical engineering

- Industrial robotics

- Mechatronics systems

- Modeling of robotics systems

- Robotics engineering

- Foundational theory of robotics

- Introduction to robotics

See also

References

- Footnotes

- Sources

- ^ "Overview of Career in Animatronics" (PDF). National TSA Conference Competitive Events Guide. Technology Student Association. 2011.

- ^ "Animatronics Introduction". Digication, Inc. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ "Definition: an·droid". Merriam-Webster. Merriam-Webster Inc.

a robot that looks like a person

- ^ Ishiguro, Hiroshi. "Android Science — Toward a new cross-interdisciplinary framework" (PDF). Japan: Osaka University. Department of Adaptive Machine Systems. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

The main difference between robot-like robots and androids is appearance. The appearance of an android is realized by making a copy of an existing person.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Why aren't the dinosaurs called "robotic" is there a difference between that and "animatronic"?". Premier Exhibitions, Inc. 2014. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

Animatronics is technology used to create machines that represent living things .. Robots designed to imitate humans are called androids.

- ^ Shooter, P.E., Steven B. "Animatronics". Mechanical Engineering Dept. Bucknell University. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ "Define: animatronics". Oxford Dictionary. Oxford University Press.

The technique of making and operating lifelike robots

- ^ "the definition of animatronic".

- ^ Kiniry, Laura. "6 Cool—And Creepy—Animatronic Advancements". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- ^ Ackerman, James S. (1997). "Villard de Honnecourt's Drawings of Reims Cathedral: A Study in Architectural Representation". Artibus et Historiae. 18 (35): 41. doi:10.2307/1483536. JSTOR 1483536.

- ^ Bedini, Silvio A. (1964). "The Role of Automata in the History of Technology". Technology and Culture. 5 (1): 24. doi:10.2307/3101120. JSTOR 3101120.

- ^ Fryer, David M.; Marshall, John C. (1979). "The Motives of Jacques de Vaucanson". Technology and Culture. 20 (2): 257. doi:10.2307/3103866. JSTOR 3103866.

- ^ Riskin, Jessica (2003). "The Defecating Duck, or, the Ambiguous Origins of Artificial Life". Critical Inquiry. 29 (4): 599–633. doi:10.1086/377722.

- ^ a b "An introduction to Animatronics". Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- ^ a b Corporation, Bonnier (Jan 1939). "A Mechanical Horse Gallops Realistically". Popular Science. 134 (1): 117. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- ^ "UTHM Hand: Mechanics Behind The Dexterous Anthropomorphic Hand". World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology. 74: 331. 2011. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-35197-6_13. ISBN 978-3-642-35196-9. ISSN 1865-0929. Archived from the original on 2005-08-01. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Ayala, Alfredo Medina (22 October 2010). Advances in New Technologies, Interactive Interfaces, and Communicability First International Conference Papers (1st ed.). Huerta Grande, Argentina: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 8–15. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-20810-2_2. ISBN 978-3-642-20809-6.

- ^ Webb, Michael (1983). "The Robots Are Here! The Robots Are Here!". Design Quarterly (121): 4. doi:10.2307/4091102. JSTOR 4091102.

- ^ Clark, Eric (2007). The Real Toy Story. Free Press. ISBN 978-0-7432-9889-6. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- ^ Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China. Vol. 2. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd. p. 53.

It walked with rapid strides, moving its head up and down, so that anyone would have taken it for a live human being.

- ^ Needham, Volume 2, 54

- ^ a b Shirbon, Estelle (14 August 2009). "Da Vinci's lion prowls again after 500 years". Reuters. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ^ a b Moran, M. E. (December 2006). "The da Vinci robot". J. Endourol. 20 (12): 986–90. doi:10.1089/end.2006.20.986. PMID 17206888.

... the date of the design and possible construction of this robot was 1495 ... Beginning in the 1950s, investigators at the University of California began to ponder the significance of some of da Vinci's markings on what appeared to be technical drawings ... It is now known that da Vinci's robot would have had the outer appearance of a Germanic knight.

- ^ a b c "The Real History of Animatronics". Rogers Studios. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- ^ Molesworth (1914). The Cuckoo Clock. JB Lippincott Company. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- ^ Kircher, Athanasius (1650). Musurgia Universalis sive Ars magna consoni & dissoni. Vol. 2. Rome. p. 343f and Plate XXI.

- ^ Miller, Justin (2012). Rare and Unusual Black Forest Clocks. Schiffer. p. 30.

- ^ Sill, Christina Rose (2013-04-10). "A Survey of Androids and Audiences: 285 BCE to the Present Day" (PDF). Simon Fraser University: 1, 16.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Bowles, Edmund A. (1953). "Instruments at the Court of Burgundy (1363-1467)". The Galpin Society Journal. 6. Galpin Society: 41. doi:10.2307/841716. JSTOR 841716.

- ^ "Bellicorum Instrumentorum Liber | The Faith of a Heretic". www.krauselabs.net. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ^ Riskin, Jessica, ed. (2007). Genesis Redux: Essays in the History and Philosophy of Artificial Life ([Online-Ausg.]. ed.). Chicago [u.a.]: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226720807.

- ^ Johnston, Cassey (June 13, 2014). "How Disney built and programmed an animatronic president". Ars Technica. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- ^ "The History of Disney's Audio Animatronics". Magical Kingdoms. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ^ a b c Pierce, Todd James. "Beyond Lincoln: Walt's Vision for Animatronics in 1965". Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ^ a b Gluck, Keith (2013-06-18). "The Early Days of Audio-Animatronics". San Francisco, CA: The Walt Disney Family Museum. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

The Walt Disney Family Museum is not affiliated with The Walt Disney Company.

[permanent dead link] - ^ "Real Life Canvas: Animating with Animatronics". DizFanatic.com. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- ^ Levelbest Communications (2005-05-06). "Walt Disney World — Disney World Vacation Information Guide — INTERCOT — Walt Disney World Inside & Out — Theme Parks". Intercot. Archived from the original on 2014-08-24. Retrieved 2014-08-04.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "MousePlanet Park Guide — Walt Disney World — Lucky the Dinosaur". Mouseplanet.com. 2010-06-19. Retrieved 2014-08-04.

- ^ Luca, Bill (2003). "My Gal Sal". Laff In The Dark.com. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- ^ "Laffing Sal (automation)". Musée Mécanique. Archived from the original on 14 August 2007. Retrieved 10 August 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "How do they do that? With animatronics!". Custom Entertainment Solutions. 2013-02-13. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- ^ Stack, Tim; Staskiewicz, Keith (2013-04-04). "Welcome to 'Jurassic Park': An oral history". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2014-09-29.

- ^ a b Corliss, Richard (26 April 1993). "Behind the Magic of Jurassic Park". TIME. Retrieved 26 January 2007.

- ^ Magid, Ron (June 1993). "Effects Team Brings Dinosaurs Back from Extinction". American Cinematographer. 74 (6): 46–52. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

But this system achieved its most remarkable results in Jurassic Park's star attraction, a 40-foot-long, 9000-pound animatronic machine that perfectly recreated the appearance and fluid motion of a full-sized Tyrannosaurus rex.

- ^ Cohen, Matt (2012-04-05). "Why Jurassic Park was meant to be seen in 3D". THE WEEK Publications, Inc. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

Spielberg's dinosaurs were breathtakingly — and terrifyingly — realistic.

- ^ Neale, Beren. "How Jurassic Park made cinematic history". 3D World (182). Retrieved 21 October 2014.

Seeing Jurassic Park made me realise that my destiny was in digital

- ^ a b c von Stamm, Bettina (19 May 2008). Managing Innovation, Design and Creativity (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780470510667. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- ^ McCarthy, Erin (2 April 2010). "Craig Ferguson's New Mythbuster Robot Sidekick: Exclusive Pics". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- ^ "2007 Gold Effie Winner — Comcast "The Slowskys"" (PDF). Amazon Web Service. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ Roberts, Tom (12 August 2009). "Animatronics – with added bite". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Robert (May 1, 2010). Designing and Constructing an Animatronic Head Capable of Human Motion Programmed using Face-Tracking Software (PDF). Graduate Capstone Project Report (M.Sc.). Worcester Polytechnic Institute. Docket etd-050112-072212. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ^ Tyson, Jeff. "How Animatronics Work". How Stuff Works. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ a b Wise, Edwin (2000). Animatronics: A Guide to Animated Holiday Displays. Cengage Learning. p. 9. ISBN 0790612194.

- ^ Buffington, Jack. "Arvid's Eyes". Buffington Effects. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- ^ James, Thurston (1997). The prop builder's molding & casting handbook (6. pr. ed.). Cincinnati: Betterway Books. p. 51. ISBN 1-55870-128-1.

- ^ a b c Buffington, Jack. "Skin and Molds". BuffingtonFX.

- ^ Miller, Ron (2006). Special Effects: An Introduction to Movie Magic. Twenty-First Century Books.

- ^ Chan, Normal (15 August 2012). "Synthetic Skin For Animatronic Robots Gets More Realistic". Whalerock Industries. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- ^ Baygan, Lee (1988). Techniques of three-dimensional makeup. New York, NY: Watson-Guptill. p. 100. ISBN 0-8230-5261-3.

- ^ a b James, Thurston (1997). The prop builder's molding & casting handbook (6. pr. ed.). Cincinnati: Betterway Books. p. 55. ISBN 1-55870-128-1.

- ^ Whelan, Tony (1994). Polymer Technology Dictionary. Springer Netherlands. pp. 144–168. doi:10.1007/978-94-011-1292-5_8.

- ^ Kornbluh, Roy D; Pelrine, Ron; Qibing, Pei; Heydt, Richard; Stanford, Scott; Oh, Seajin; Eckerle, Joseph (July 9, 2002). "Electroelastomers: applications of dielectric elastomer transducers for actuation, generation, and smart structures". Smart Structures and Material. Smart Structures and Materials 2002: Industrial and Commercial Applications of Smart Structures Technologies. Applications of Smart Structures Technologies (254): 254. Bibcode:2002SPIE.4698..254K. doi:10.1117/12.475072.

- ^ Ekman, Paul; Friesen, Wallace V. (1975). Unmasking the face : a guide to recognizing emotions from facial clues (PDF) (2. [pr.] ed.). Englewood Cliffs, N. J.: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 9780139381751. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ^ Ortony, Andrew; Clore, Gerald L.; Collins, Allan (1988). "The Cognitive Structure of Emotions" (PDF). Cambridge University Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-11-23.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ribeiro, Tiago; Paiva, Ana. "The Illusion of Robotic Life" (PDF). Porto Salvo, Portugal: INESC-ID. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Animatronics Degree Programs with Career Information". Education Career Articles. 25 March 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2014.