Box jellyfish

| Box Jellyfish | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chironex sp. | |

| |

| Carukia barnesi | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | Cubozoa Werner, 1975

|

| Orders | |

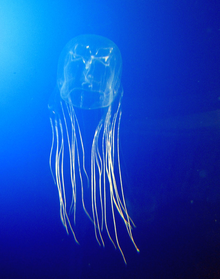

Box jellyfish (class Cubozoa) are cnidarian invertebrates distinguished by their cube-shaped medusae. Some species of box jellyfish produce extremely potent venom: Chironex fleckeri, Carukia barnesi and Malo kingi are among the most venomous creatures in the world. Stings from these and a few other species in the class are extremely painful and can be fatal to humans.

Nomenclature

"Box jellyfish" and "sea wasp" are common names for the highly venomous Chironex fleckeri.[1] However, these terms are ambiguous, as "sea wasp" and "marine stinger" are sometimes used to refer to other jellyfish.

Anatomy

Box jellyfish most visibly differ from the Scyphozoan jellyfish in that they are rounded box shape, rather than domed or crown-shaped. The underside of the umbrella includes a flap, or velarium, concentrating and increasing the flow of water expelled from the umbrella. As a result, box jellyfish can move more rapidly than other jellyfish. In fact, speeds of up to six meters per minute have been recorded.[2]

The box jellyfish's nervous system is also more developed than that of many other jellyfish. Notably, they possess a nerve ring around the base of the umbrella that coordinates their pulsing movements; a feature found elsewhere only in the crown jellyfish. Whereas some other jellyfish do have simple pigment-cup ocelli, box jellyfish are unique in the possession of true eyes, complete with retinas, corneas and lenses. Their eyes are located on each of the four sides of their bell in clusters called rhopalia. This enables them to see specific points of light, as opposed to simply distinguishing between light and the dark. Box jellyfish also have 20 ocelli (simple eyes), that do not form images but detect light and dark; they therefore have a total of 24 eyes.[3] Box jellyfish also display complex, probably visually guided behaviors such as obstacle avoidance and fast directional swimming.[4] Research indicates that, owing to the number of rhopalial nerve cells and their overall arrangement, visual processing and integration at least partly happen within the rhopalia of box jelly fish.[4] The complex nervous system supports a relatively advanced sensory system compared to other jellyfish, and their behavior has been described as more fish-like.[5]

Some species have tentacles that can reach up to 3 m (9.8 ft) in length. Box jellyfish can weigh up to 2 kg (4.4 lb).[6]

Distribution

Although the venomous species of box jellyfish are almost entirely restricted to the tropical Indo-Pacific, various species of box jellyfish can be found widely in tropical and subtropical oceans, including the Atlantic and east Pacific, with species as far north as California, the Mediterranean (for example, Carybdea marsupialis)[7] and Japan (such as Chironex yamaguchii),[8] and as far south as South Africa (for example, Carybdea branchi)[9] and New Zealand (such as Carybdea sivickisi).[10]

Defense and feeding mechanisms

The box jellyfish actively hunts its prey (small fish), rather than drifting as do true jellyfish. They are capable of achieving speeds of up to 1.5 to 2 metres per second or about 4 knots (7.4 km/h; 4.6 mph).[6]

A fully grown box jellyfish can measure up to 20 cm (7.9 in) along each box side (or 30 cm (12 in) in diameter), and the tentacles can grow up to 3 m (9.8 ft) in length. Its weight can reach 2 kg (4.4 lb). There are about 15 tentacles on each corner. Each tentacle has about 500,000 cnidocytes, containing nematocysts, a harpoon-shaped microscopic mechanism that injects venom into the victim.[11] Many different kinds of nematocysts are found in cubozoans.[12]

The venom of cubozoans is distinct from that of scyphozoans, and is used to catch prey (small fish and invertebrates, including prawns and bait fish) and for defence from predators, which include the butterfish, batfish, rabbitfish, crabs (Blue Swimmer Crab) and various species of sea turtles (hawksbill turtle, flatback turtle). Sea turtles, however, are apparently unaffected by the sting and eat box jellyfish.[6]

Box jellyfish can see. They have clusters of eyes on each side of the box. Some of those eyes are surprisingly sophisticated, with a lens and cornea, an iris that can contract in bright light, and a retina. Their speed and vision leads some researchers to believe that box jellyfish actively hunt their prey, others insist they are passive opportunists, meaning they just hang around and wait for prey to bump into their tentacles.[citation needed]

Danger to humans

Although the box jellyfish has been called "the world's most venomous creature",[13] only a few species in the class have been confirmed to be involved in human deaths, and some species pose no serious threat at all. For example, the sting of Chiropsella bart only results in short-lived itching and mild pain.[14]

In Australia, fatalities are most often perpetrated by the largest species of this class of jellyfish, Chironex fleckeri. Angel Yanagihara of the University of Hawaii's Department of Tropical Medicine found the venom causes cells to become porous enough to allow potassium leakage, causing hyperkalemia, which can lead to cardiovascular collapse and death as quickly as within 2 to 5 minutes. She postulated that a zinc compound may be developed as an antidote.[15]

The recently discovered and very similar Chironex yamaguchii may be equally dangerous, as it has been implicated in several deaths in Japan.[8] It is unclear which of these species is the one usually involved in fatalities in the Malay Archipelago.[8][16] In 1990, a 4-year-old child died after being stung by Chiropsalmus quadrumanus at Galveston Island in the Gulf of Mexico, and either this species or Chiropsoides buitendijki are considered the likely perpetrators of two deaths in West Malaysia.[16] At least two deaths in Australia have been attributed to the thumbnail-sized Irukandji jellyfish.[17][18] Those who fall victim to these may suffer severe physical and psychological symptoms, known as Irukandji syndrome.[19] Nevertheless, most victims do survive, and out of 62 people treated for Irukandji envenomation in Australia in 1996, almost half could be discharged home with few or no symptoms after 6 hours, and only two remained hospitalized approximately a day after they were stung.[19]

In Australia, C. fleckeri has caused at least 64 deaths since the first report in 1883,[20] but even in this species most encounters appear to only result in mild envenoming.[21] Most recent deaths in Australia have been in children, which is linked to their smaller body mass.[20] In parts of the Malay Archipelago, the number of lethal cases is far higher (in the Philippines alone, an estimated 20-40 die annually from Chirodropid stings), likely due to limited access to medical facilities and antivenom, and the fact that many Australian beaches are enclosed in nets and have vinegar placed in prominent positions allowing for rapid first aid.[21][22] Vinegar is also used as treatment by locals in the Philippines.[16] Nevertheless, some researchers believe that using vinegar can be deadly.[23]

Box jellyfish are known as the "suckerpunch" of the sea not only because their sting is rarely detected until the venom is injected, but also because they are almost transparent.[24]

In northern Australia, the highest risk period for the box jellyfish is between October and May, but stings and specimens have been reported all months of the year. Similarly, the highest risk conditions are those with calm water and a light, onshore breeze; however, stings and specimens have been reported in all conditions.

In Hawaii, box jellyfish numbers peak approximately 7 to 10 days after a full moon, when they come near the shore to spawn. Sometimes the influx is so severe that lifeguards have closed infested beaches, such as Hanauma Bay, until the numbers subside.[25][26]

Treatment of stings

‹The template How-to is being considered for merging.›

This section contains instructions, advice, or how-to content. (March 2013) |

Once a tentacle of the box jellyfish adheres to skin, it pumps nematocysts with venom into the skin, causing the sting and agonizing pain. Pressure immobilisation can be used on limbs to slow down the spreading of the deadly venom. Flushing with vinegar, once believed to be useful at neutralizing the tentacle stinging apparatus of box jellyfish, has been shown to amplify rather than palliate the effects of a box jellyfish sting.[27]

Removal of additional tentacles is usually done with a towel or gloved hand, to prevent secondary stinging. Tentacles will still sting if separated from the bell, or after the creature is dead. Removal of tentacles may cause unfired nematocysts to come into contact with the skin and fire, resulting in a greater degree of envenomation.[citation needed]

Although commonly recommended in folklore and even some papers on sting treatment,[28] there is no scientific evidence that urine, ammonia, meat tenderizer, sodium bicarbonate, boric acid, lemon juice, fresh water, steroid cream, alcohol, cold packs, papaya, or hydrogen peroxide will disable further stinging, and these substances may even hasten the release of venom.[29] Heat packs have been proven for moderate pain relief.[30] Pressure immobilization bandages, methylated spirits, or vodka should never be used for jelly stings.[31][32][33][34] In severe Chironex fleckeri stings cardiac arrest can occur quickly.

In 2011, University of Hawaii Assistant Research Professor Angel Yanagihara announced that she had developed an effective treatment by "deconstructing" the venom contained in the box jellyfish tentacles.[35] Its effectiveness was demonstrated in the PBS NOVA documentary Venom: Nature's Killer, originally shown on North American television in February 2012.[36]

Protection during swimming or diving

Wearing pantyhose or full body lycra suits during diving (both by women and men, also under scuba-diving suit) is an effective protection against box jellyfish stings.[37] The pantyhose were formerly thought to work because of the length of the box jellyfish's stingers (nematocysts), but it is now known to be related to the way the stinger cells work. The stinging cells on a box jellyfish's tentacles are not triggered by touch, but are instead triggered by the chemicals found on skin.[citation needed]

Taxonomy

As of 2007, at least 36 species of box jellyfish were known.[38] These are grouped into two orders and seven families.[39] A few new species have been described since then, and it is likely undescribed species remain.[8][9][14]

Class Cubozoa

- Order Carybdeida

- Family Alatinidae

- Family Carukiidae

- Family Carybdeidae

- Family Tamoyidae

- Family Tripedaliidae

- Order Chirodropida

- Family Chirodropidae

- Family Chiropsalmidae

- Chiropsalmus Agassiz, 1862

- Chiropsella Gershwin, 2006

- Chiropsoides Southcott, 1956

References

- ^ Chironex fleckeri at Encyclopedia of Life

- ^ Barnes, Robert D. (1982). Invertebrate Zoology. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 139–49. ISBN 0-03-056747-5.

- ^ "Jellyfish Have Human-Like Eyes". LiveScience. 2007-04-01. Retrieved 2012-08-27.

- ^ a b Skogh C, Garm A, Nilsson DE, Ekström P (December 2006). "Bilaterally symmetrical rhopalial nervous system of the box jellyfish Tripedalia cystophora". Journal of Morphology. 267 (12): 1391–405. doi:10.1002/jmor.10472. PMID 16874799.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nilsson DE, Gislén L, Coates MM, Skogh C, Garm A (May 2005). "Advanced optics in a jellyfish eye". Nature. 435 (7039): 201–5. doi:10.1038/nature03484. PMID 15889091.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c USA. "Box Jellyfish, Box Jellyfish Pictures, Box Jellyfish Facts". NationalGeographic.com. Retrieved 2012-08-27.

- ^ Carybdea marsupialis. The Jellies Zone. Retrieved April 28, 2010

- ^ a b c d Lewis C, Bentlage B (2009). "Clarifying the identity of the Japanese Habu-kurage, Chironex yamaguchii, sp nov (Cnidaria: Cubozoa: Chirodropida)" (PDF). Zootaxa. 2030: 59–65.

- ^ a b Gershwin L, Gibbons M (2009). "Carybdea branchi, sp. nov., a new box jellyfish (Cnidaria: Cubozoa) from South Africa" (PDF). Zootaxa. 2088: 41–50.

- ^ Gershwin L (2009). "Staurozoa, Cubozoa, Scyphozoa (Cnidaria)". In Gordon D (ed.). New Zealand Inventory of Biodiversity. Vol. 1: Kingdom Animalia.[page needed]

- ^ Williamson JA, Fenner P J, Burnett JW, Rifkin J., ed. (1996). Venomous and poisonous marine animals: a medical and biological handbook. Surf Life Saving Australia and University of New North Wales Press Ltd. ISBN 0-86840-279-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link)[page needed] - ^ Gershwin, L (2006). "Nematocysts of the Cubozoa" (PDF). Zootaxa (1232): 1–57.

- ^ "Girl survives sting by world's deadliest jellyfish". Daily Telegraph. London. 27 April 2010. Retrieved 11 Dec 2010.

- ^ a b Gershwin, L. A.; Alderslade, P (2006). "Chiropsella bart n. sp., a new box jellyfish (Cnidaria: Cubozoa: Chirodropida) from the Northern Territory, Australia" (PDF). The Beagle, Records of the Museums and Art Galleries of the Northern Territory. 22: 15–21.

- ^ Salleh, Anna (13 December 2012). "Box jelly venom under the microscope". Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c Fenner PJ (1997). The Global Problem of Cnidarian (Jellyfish) Stinging (PhD Thesis). London: London University. OCLC 225818293.[page needed]

- ^ Fenner PJ, Hadok JC (October 2002). "Fatal envenomation by jellyfish causing Irukandji syndrome". The Medical Journal of Australia. 177 (7): 362–3. PMID 12358578.

- ^ Gershwin, L (2007). "Malo kingi: A new species of Irukandji jellyfish (Cnidaria: Cubozoa: Carybdeida), possibly lethal to humans, from Queensland, Australia". Zootaxa. 1659: 55–68.

- ^ a b Little M, Mulcahy RF (1998). "A year's experience of Irukandji envenomation in far north Queensland". The Medical Journal of Australia. 169 (11–12): 638–41. PMID 9887916.

- ^ a b Centre for Disease Control (November 2012). "Chironex fleckeri" (PDF). Northern Territory Government Department of Health.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Daubert, G. P. (2008). "Cnidaria Envenomation". eMedicine.

- ^ Fenner PJ, Williamson JA (1996). "Worldwide deaths and severe envenomation from jellyfish stings". The Medical Journal of Australia. 165 (11–12): 658–61. PMID 8985452.

- ^ Vinegar on jellyfish sting can be deadly: researchers Sydney Morning Herald. 2014.

- ^ "Facts About Box Jellyfish". iloveindia.com. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ^ "Jellyfish: A Dangerous Ocean Organism of Hawaii". Retrieved 6/10/2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Hanauma Bay closed for second day due to box jellyfish". Retrieved 6/10/2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Vinegar on jellyfish sting can be deadly". 2014-04-08. Retrieved 2014-04-08.

- ^ Zoltan T, Taylor K, Achar S (2005). "Health issues for surfers". Am Fam Physician. 71 (12): 2313–7. PMID 15999868.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fenner P (2000). "Marine envenomation: An update – A presentation on the current status of marine envenomation first aid and medical treatments". Emerg Med Australasia. 12 (4): 295–302. doi:10.1046/j.1442-2026.2000.00151.x.

- ^ Taylor, G. (2000). "Are some jellyfish toxins heat labile?". South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society journal. 30 (2). ISSN 0813-1988. OCLC 16986801. Retrieved 2013-11-15.

- ^ Hartwick R, Callanan V, Williamson J (1980). "Disarming the box-jellyfish: nematocyst inhibition in Chironex fleckeri". Med J Aust. 1 (1): 15–20. PMID 6102347.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Seymour J, Carrette T, Cullen P, Little M, Mulcahy R, Pereira P (2002). "The use of pressure immobilization bandages in the first aid management of cubozoan envenomings". Toxicon. 40 (10): 1503–5. doi:10.1016/S0041-0101(02)00152-6. PMID 12368122.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Little M (June 2002). "Is there a role for the use of pressure immobilization bandages in the treatment of jellyfish envenomation in Australia?". Emerg Med (Fremantle). 14 (2): 171–4. doi:10.1046/j.1442-2026.2002.00291.x. PMID 12164167.

- ^ Pereira PL, Carrette T, Cullen P, Mulcahy RF, Little M, Seymour J (2000). "Pressure immobilisation bandages in first-aid treatment of jellyfish envenomation: current recommendations reconsidered". Med. J. Aust. 173 (11–12): 650–2. PMID 11379519.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ UHMedNow, "Angel Yanagihara's box jellyfish venom research leads to sting treatment", March 4, 2011

- ^ PBS Nova, Venom: Nature's Killer (transcript)

- ^ http://lifehacker.com/5560147/use-pantyhose-to-protect-yourself-from-jellyfish-stings[full citation needed][unreliable source?]

- ^ Daly, Marymegan; et al. (2007). "The phylum Cnidaria: A review of phylogenetic patterns and diversity 300 years after Linnaeus" (PDF). Zootaxa (1668): 127–182.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author2=(help) - ^ Bentlage B, Cartwright P, Yanagihara AA, Lewis C, Richards GS, Collins AG (February 2010). "Evolution of box jellyfish (Cnidaria: Cubozoa), a group of highly toxic invertebrates". Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 277 (1680): 493–501. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.1707. PMC 2842657. PMID 19923131.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- Cubozoa classification

- ThinkQuest: Box jellyfish, Boxfish, Deadly sea wasp

- Box Jellyfish – Jellyfish Facts

- Box Jelly Fish, dangers on the great barrier reef

- Jellyfish eyes

- Jellyfish Predictions Waikiki, Hawai'i

- Box Jellyfish by an Australian toxicologist

- Daily Telegraph

- Box Jellyfish | Smithsonian's Ocean Portal

- Zimbio

- Box Jellyfish images