Chaldean Catholics

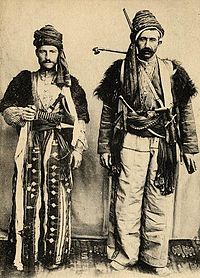

Chaldean Catholics from Mardin, 19th century. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 490,371(2010)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 230,071(2012)[2] | |

| 30,000(2012)[3] | |

| 3,900(2014)[2] | |

| 7,640 (2013)[4] | |

| Diaspora | Several hundred thousand |

| 235,000 (2014)[2] | |

| 9,005 (by ancestry, 2011 Census)[5] 35,000 (according to The Hierarchy of the Catholic Church)[6] | |

| 18,668 (2013)[7] | |

| Religions | |

| Syriac Christianity (in union with Rome), Chaldean Catholic Church | |

| Scriptures | |

| The Bible | |

| Languages | |

| Neo-Aramaic (Assyrian Neo-Aramaic, Chaldean Neo-Aramaic), Arabic | |

Chaldean Christians /kælˈdiːən/ (ܟܠܕܝ̈ܐ), also known as Kaldaye and Kaldanaye, are ethnic Chaldeans.[8][9] Syriac Christian adherents of the Chaldean Catholic Church which emerged from Mosul in 1681 and from the Church of the East in 1830.[10][11] Assyrians are mentioned as a distinct ethnic group in Article 125 of the Iraqi constitution.[12]

While originating in Chaldea in Mesopotamia and the wider region (north of Iraq, southeast Turkey and northeast Syria), many Chaldean Catholic Christians have migrated to Western countries like the USA, Canada, Australia, Sweden and Germany. Many of them also live in Lebanon, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Iran, Turkey and Georgia. The reasons for migration are the poor economic conditions during the Sanctions against Iraq, Religious persecution and Ethnic persecution and poor security conditions after the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

Etymology

The terms Chaldean'is used to describe the group who broke from the Church of the East in what is known as the Schism of 1552 and entered into communion with the Roman Catholic Church, after at first failing to gain acceptance within the Syriac Orthodox Church.[13] Rome initially named this new church structure The Church of Assyria and Mosul in 1553, and only some 128 years later, in 1681, was this changed to The Chaldean Catholic Church, despite none of its adherents (or neighbouring peoples) having hitherto used the name "Chaldean" to describe themselves or their church,[14][15][16] or having originated in the region in the far south of Mesopotamia which had long ago once been Chaldea. Ironically, The Church of Athura and Mosul later returned to the doctrines of the Assyrian Church of the East and split away from the Catholic church, while still keeping its independence from the Nestorian Church structure based in Alqosh that they split from in 1552. However, The original line of the Assyrian Church they broke from joined the Chaldean Catholic Church in 1830, which therefore made the Church of Athura and Mosul the modern day Assyrian Church of the East.[17]

The term Chaldean in reference to followers of the Chaldean Catholic Church is thus properly taken as only a denominational, doctrinal, theological and ecclesiastical term which only arose in the late 17th century AD and became fully established in the 19th century AD (in the same sense as Baptist, Mormon, Nestorian and Methodist) and not an ethnic one, and is a misnomer in relation to ancient Chaldea and its inhabitants, both of which only emerged during the 9th century BC after Chaldean tribes migrated to south east Mesopotamia from the Levant, and disappeared from history during the 6th century BC at the exact opposite end of Mesopotamia.[18][19][19]

Raphael Bidawid, the then patriarch of the Chaldean Catholic Church commented on the Assyrian name dispute in 2003 and clearly differentiated between the name of a church and an ethnicity:

- "I personally think that these different names serve to add confusion. The original name of our Church was the ‘Church of the East’ … When a portion of the Church of the East became Catholic in the 17th Century, the name given was ‘Chaldean’ based on the Magi kings who were believed by some to have come from what once had been the land of the Chaldean, to Bethlehem. The name ‘Chaldean’ does not represent an ethnicity, just a church… We have to separate what is ethnicity and what is religion… I myself, my sect is Chaldean, but ethnically, I am Assyrian."[9]

In an interview with the Assyrian Star in the September–October 1974 issue, he was quoted as saying:

- "Before I became a priest I was an Assyrian, before I became a bishop I was an Assyrian, I am an Assyrian today, tomorrow, forever, and I am proud of it."[20]

History

The 1896 census of the Chaldean Catholics[21] counted 233 parishes and 177 churches or chapels, mainly in northern Iraq and southeastern Turkey. The Chaldean Catholic clergy numbered 248 priests; they were assisted by the monks of the Congregation of St. Hormizd, who numbered about one hundred. There were about 52 Assyrian Chaldean schools (not counting those conducted by Latin nuns and missionaries). At Mosul there was a patriarchal seminary, distinct from the Chaldean seminary directed by the Dominicans. The total number of Assyrian Chaldean Christians as by 2010 was 490,371,[1] 78,000 of whom are in the Diocese of Mosul.

The current patriarch considers Baghdad as the principal city of his see. His title of "Patriarch of Babylon" results from the identification of Baghdad with ancient Babylon (however Baghdad is 55 miles north of the ancient city of Babylon and corresponds to northern Babylonia). However, the Chaldean patriarch resides habitually at Mosul in the north, and reserves for himself the direct administration of this diocese and that of Baghdad.

There are five archbishops (resident respectively at Basra, Diyarbakır, Kirkuk, Salmas and Urmia) and seven bishops. Eight patriarchal vicars govern the small Assyrian Chaldean communities dispersed throughout Turkey and Iran. The Chaldean clergy, especially the monks of Rabban Hormizd Monastery, have established some missionary stations in the mountain districts dominated by The Assyrian Church of the East. Three dioceses are in Iran, the others in Turkey.

The liturgical language of the Chaldean Catholic Church is Syriac, a distinctly north Mesopotamian Neo-Aramaic dialect originating in 5th century BC Achaemenid Assyria (Athura) during the Achaemenid Empire. The liturgy of the Chaldean Church is written in the Syriac alphabet.

The literary revival in the early 20th century was mostly due to the Lazarist Pere Bedjan, an ethnic Assyrian Chaldean Catholic from north western Iran. He popularized the ancient chronicles, the lives of Assyrian saints and martyrs, and even works of the ancient Assyrian doctors among Assyrians of all denominations, including Chaldean Catholics, Syriac Orthodox, Assyrian Church of the East and Assyrian Protestants.[22]

In March 2008, Chaldean Catholic Archbishop Paulos Faraj Rahho of Mosul was kidnapped, and found dead two weeks later. Pope Benedict XVI condemned his death. Sunni and Shia leaders also expressed their condemnation.[23]

Chaldean Catholics today number approximately 550,000 of Iraq's estimated 800,000-1,000,000 Assyrian Christians, with smaller numbers found among the Assyrian Christian communities of northeast Syria, southeast Turkey, northwest Iran, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, Georgia and Armenia.[11] Perhaps the best known Iraqi Chaldean Catholic is former Iraqi deputy prime minister, Tariq Aziz (real name Michael Youhanna).[11]

Hundreds of thousands of Assyrian Christians of all denominations have left Iraq since the ousting of Saddam Hussein in 2003. At least 20,000 of them have fled through Lebanon to seek resettlement in Europe and the US.[24]

As political changes sweep through many Arab nations, the ethnic Assyrian minorities in northeast Syria, northwest Iran and southeast Turkey have also expressed concern.[25]

Historic statistics of Chaldean Catholic Christians

Church censuses can be used to determine how many Chaldean Catholics there were.

| Diocese | No. of Villages | No. of Churches | No. of Priests | No. of Families | Diocese | No. of Villages | No. of Churches | No. of Priests | No. of Families |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mosul | 9 | 15 | 20 | 1,160 | Seert | 11 | 12 | 9 | 300 |

| Baghdad | 1 | 1 | 2 | 60 | Gazarta | 7 | 6 | 5 | 179 |

| ʿAmadiya | 16 | 14 | 8 | 466 | Kirkuk | 7 | 8 | 9 | 218 |

| Amid | 2 | 2 | 4 | 150 | Salmas | 1 | 2 | 3 | 150 |

| Mardin | 1 | 1 | 4 | 60 | Total | 55 | 61 | 64 | 2,743 |

Paulin Martin's statistical survey in 1867, after the creation of the dioceses of ʿAqra, Zakho, Basra and Sehna by Joseph Audo, recorded a total church membership of 70,268, more than three times higher than Badger's estimate. Most of the population figures in these statistics have been rounded up to the nearest thousand, and they may also have been exaggerated slightly, but the membership of the Chaldean church at this period was certainly closer to 70,000 than to Badger's 20,000.[26]

| Diocese | No. of Villages | No. of Priests | No. of Believers | Diocese | No. of Villages | No. of Churches | No. of Believers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mosul | 9 | 40 | 23,030 | Mardin | 2 | 2 | 1,000 |

| ʿAqra | 19 | 17 | 2,718 | Seert | 35 | 20 | 11,000 |

| ʿAmadiya | 26 | 10 | 6,020 | Salmas | 20 | 10 | 8,000 |

| Basra | – | – | 1,500 | Sehna | 22 | 1 | 1,000 |

| Amid | 2 | 6 | 2,000 | Zakho | 15 | – | 3,000 |

| Gazarta | 20 | 15 | 7,000 | Kirkuk | 10 | 10 | 4,000 |

| Total | 160 | 131 | 70,268 |

A statistical survey of the Chaldean church made in 1896 by J. B. Chabot included, for the first time, details of several patriarchal vicariates established in the second half of the 19th century for the small Chaldean communities in Adana, Aleppo, Beirut, Cairo, Damascus, Edessa, Kermanshah and Teheran; for the mission stations established in the 1890s in several towns and villages in the Qudshanis patriarchate; and for the newly created Chaldean diocese of Urmi. According to Chabot, there were mission stations in the town of Serai d’Mahmideh in Taimar and in the Hakkari villages of Mar Behıshoʿ, Sat, Zarne and 'Salamakka' (Ragula d'Salabakkan).[27]

| Diocese | No. of Villages | No. of Priests | No. of Believers | Diocese | No. of Villages | No. of Churches | No. of Believers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baghdad | 1 | 3 | 3,000 | ʿAmadiya | 16 | 13 | 3,000 |

| Mosul | 31 | 71 | 23,700 | ʿAqra | 12 | 8 | 1,000 |

| Basra | 2 | 3 | 3,000 | Salmas | 12 | 10 | 10,000 |

| Amid | 4 | 7 | 3,000 | Urmi | 18 | 40 | 6,000 |

| Kirkuk | 16 | 22 | 7,000 | Sehna | 2 | 2 | 700 |

| Mardin | 1 | 3 | 850 | Vicariates | 3 | 6 | 2,060 |

| Gazarta | 17 | 14 | 5,200 | Missions | 1 | 14 | 1,780 |

| Seert | 21 | 17 | 5,000 | Zakho | 20 | 15 | 3,500 |

| Total | 177 | 248 | 78,790 |

The last pre-war survey of the Chaldean church was made in 1913 by the Chaldean priest Joseph Tfinkdji, after a period of steady growth since 1896. The Chaldean church on the eve of the First World War consisted of the patriarchal archdiocese of Mosul and Baghdad, four other archdioceses (Amid, Kirkuk, Seert and Urmi), and eight dioceses (ʿAqra, ʿAmadiya, Gazarta, Mardin, Salmas, Sehna, Zakho and the newly created diocese of Van). Five more patriarchal vicariates had been established since 1896 (Ahwaz, Constantinople, Basra, Ashshar and Deir al-Zor), giving a total of twelve vicariates.[28]

Tfinkdji's grand total of 101,610 Catholics in 199 villages is slightly exaggerated, as his figures included 2,310 nominal Catholics in twenty-one 'newly converted' or 'semi-Nestorian' villages in the dioceses of Amid, Seert and ʿAqra, but it is clear that the Chaldean church had grown significantly since 1896. With around 100,000 believers in 1913, the membership of the Chaldean church was only slightly smaller than that of the Qudshanis patriarchate (probably 120,000 East Syrians at most, including the population of the nominally Russian Orthodox villages in the Urmi district). Its congregations were concentrated in far fewer villages than those of the Qudshanis patriarchate, and with 296 priests, a ratio of roughly three priests for every thousand believers, it was rather more effectively served by its clergy. Only about a dozen Chaldean villages, mainly in the Seert and ʿAqra districts, did not have their own priests in 1913.

| Diocese | No. of Villages | No. of Churches | No. of Priests | No. of Believers | Diocese | No. of Villages | No. of Churches | No. of Priests | No. of Believers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mosul | 13 | 22 | 56 | 39,460 | ʿAmadiya | 17 | 10 | 19 | 4,970 |

| Baghdad | 3 | 1 | 11 | 7,260 | Gazarta | 17 | 11 | 17 | 6,400 |

| Vicariates | 13 | 4 | 15 | 3,430 | Mardin | 6 | 1 | 6 | 1,670 |

| Amid | 9 | 5 | 12 | 4,180 | Salmas | 12 | 12 | 24 | 10,460 |

| Kirkuk | 9 | 9 | 19 | 5,840 | Sehna | 1 | 2 | 3 | 900 |

| Seert | 37 | 31 | 21 | 5,380 | Van | 10 | 6 | 32 | 3,850 |

| Urmi | 21 | 13 | 43 | 7,800 | Zakho | 15 | 17 | 13 | 4,880 |

| ʿAqra | 19 | 10 | 16 | 2,390 | Total | 199 | 153 | 296 | 101,610 |

Tfinkdji's statistics also highlight the effect on the Chaldean church of the educational reforms of the patriarch Joseph VI Audo. The Chaldean church on the eve of the First World War was becoming less dependent on the monastery of Rabban Hormizd and the College of the Propaganda for the education of its bishops. Seventeen Chaldean bishops were consecrated between 1879 and 1913, of whom only one (Stephen Yohannan Qaynaya) was entirely educated in the monastery of Rabban Hormizd. Six bishops were educated at the College of the Propaganda (Joseph Gabriel Adamo, Thomas Audo, Jeremy Timothy Maqdasi, Isaac Khudabakhash, Theodore Msayeh and Peter ʿAziz), and the future patriarch Joseph Emmanuel Thomas was trained in the seminary of Ghazir near Beirut. Of the other nine bishops, two (Addaï Scher and Francis David) were trained in the Syro-Chaldean seminary in Mosul, and seven (Philip Yaʿqob Abraham, Yaʿqob Yohannan Sahhar, Eliya Joseph Khayyat, Shlemun Sabbagh, Yaʿqob Awgin Manna, Hormizd Stephen Jibri and Israel Audo) in the patriarchal seminary in Mosul.[29]

|

|

|

|

Predominantly Chaldean Catholic towns in northern Iraq

- Zakho

- Alqosh (ܐܠܩܘܫ)

- Ankawa (ܥܢܟܒ݂ܐ)

- Araden (ܐܪܕܢ)

- Baqofah (ܒܝܬ ܩܘܦ̮ܐ)

- Batnaya (ܒܛܢܝܐ)

- Karamles (ܟܪܡܠܫ)

- Shaqlawa(ܫܩܠܒ݂ܐ)

- Tel Isqof (ܬܠܐ ܙܩܝܦ̮ܐ)

- Tel Keppe (ܬܠ ܟܦܐ)

Chaldean nationalism

Chaldean Catholics are regarded ethnically and historically as Assyrians, and as a part of the Assyrian continuity.[20][30][31][32][33][34][35] The modern Chaldean Catholics are in fact Assyrians[36] and originated from ancient Assyrian communities living in and indigenous to the north of Iraq/Mesopotamia which was known as Assyria from the 25th century BC until the 7th century AD. However, a minority of Chaldean Catholics (particularly in the United States) have in very recent times confused a purely religious term with an ethnic identity, and espoused a separate ethnic identity to their Assyrian brethren, claiming descent from the long extinct people of ancient Chaldeans/Chaldees, who resided in the far south east of Mesopotamia and disappeared from history circa 550 BC, despite there being no scientific evidence supporting such a link.[20][37][38] Chaldean Catholics speak the same language, bear the same family and personal names, share the same genetic profile, hail from the same villages, towns and cities in northern Iraq, south east Turkey, north east Syria and north west Iran, and for most of their history were originally members of the same church as other Assyrians of the Assyrian Church of the East, Syriac Orthodox Church, Ancient Church of the East, Assyrian Pentecostal Church and Assyrian Evangelical Church.[37] Nevertheless, a minority of Chaldean Catholics, most notably Bishop Addai Scher, have attempted to invent the concept of "Chaldeans" as a nation and nationalism built on it.[39]

The first political movement of Chaldean Catholics was founded in 1972 in Iraq and named the Chaldean Patriot Movement, after Baathist regime in Iraq killed many Chaldean Catholics in the Soria village of in the Dohuk province, but then this movement resolved after the Baath regime chasing their members.[40] Official statistics in Iraq referred to all Syriac Christians, including Chaldean Catholics, as Christian Arabs. In 1972, the cultural rights of Syriac speaking Christians in Iraq were recognised by the Iraqi government, but the Baathist regime refused to recognize Assyrians as an ethnic group .[41]

After the fall of the Baath regime in Iraqi Kurdistan in 1991, some Chaldean Catholics began to establish "Chaldean nationalist" political parties around the Chaldean Catholic identity, in 1999 founded the Chaldean Democratic Party and in 2002 the Chaldean National Congress Party.[42][43] Upon their demands, the Iraqi constitution of 2005 in Article 125 mentions "Chaldeans" as an allegedly distinct ethnic group.[12] Several conferences on Chaldean nationalism were held,[44][45] and a flag designed.[46]

See also

- Assyrian Church of the East

- Ancient Church of the East

- Syriac Christianity

- Terms for Syriac Christians

- East Syrian Rite

References

- ^ a b http://www.cnewa.org/source-images/Roberson-eastcath-statistics/eastcatholic-stat10.pdf

- ^ a b c http://www.catholic-hierarchy.org/rite/dch2.html

- ^ http://www.catholic-hierarchy.org/diocese/dalpc.html

- ^ http://www.catholic-hierarchy.org/diocese/ddiar.html

- ^ "Statistics from the 2011 Census" (PDF). The People of NSW. Department of Immigration and Citizenship, Commonwealth of Australia. 2014. Table 13, Ancestry. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- ^ http://www.catholic-hierarchy.org/diocese/dsych.html

- ^ http://www.catholic-hierarchy.org/diocese/dtoch.html

- ^ Genocide in the Middle East: The Ottoman Empire, Iraq, and Sudan. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 2010, 2007, pp. 237–77, 293–294 ISBN 9781594604362

- ^ a b Parpola, Simo (2004). "National and Ethnic Identity in the Neo-Assyrian Empire and Assyrian Identity in Post-Empire Times" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 18 (2). JAAS: 22.

- ^ George V. Yana (Bebla), "Myth vs. Reality" JAA Studies, Vol. XIV, No. 1, 2000 p. 80

- ^ a b c BBC NEWS (March 13, 2008). "Who are the Chaldean Christians?". BBC NEWS. Retrieved March 26, 2010.

- ^ a b http://www.iraqinationality.gov.iq/attach/iraqi_constitution.pdf

- ^ Dr. Layla Maleh (Kuwait University) (2009). Arab Voices in Diaspora: Critical Perspectives on Anglophone Arab Literature. Rodopi. p. 396. ISBN 90-420-2718-5.

- ^ "A difficulty now arose; the new converts styled themselves 'Sooraye' and 'Nestornaye' . The Romanists could not call them 'Catholic Syrians' or 'Syrian Catholics' for this appellation they had already given to their proselytes from the Jacobites, who also called themselves 'Syrians'. They could not term them 'Catholic Nestorians,' as Mr. Justin Perkins, the independent American missionary does, for this would involve a contradiction. What more natural, then, than that they should have applied to them the title of 'Chaldeans' to which they had some claims of nationality, in virtue of their Assyrian Descent." - Asshur and the Land of Nimrod" by Hormuzd Rassam

- ^ Qaryaneh Jobyeh" - Mar Toma Audo. 1906

- ^ Arabs and Christians? Christians in the Middle East" by Antonie Wessels

- ^ D.Wilmshurst - A History of The Church of the East

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Travis, Hannibal. Genocide in the Middle East: The Ottoman Empire, Iraq, and Sudan. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 2010, 2007, pp. 237-77, 293–294

- ^ a b http://conference.osu.eu/globalization/publ/08-bohac.pdf

- ^ a b c Mar Raphael J Bidawid. The Assyrian Star. September–October, 1974:5.

- ^ Mgr. George 'Abdisho' Khayyath to the Abbé Chabot (Revue de l'Orient Chrétien, I, no. 4)

- ^ "New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia".

- ^ "Iraqi archbishop death condemned". BBC News. 2008-03-13. Retrieved 2009-12-31. from BBC News

- ^ Martin Chulov (2010) "Christian exodus from Iraq gathers pace"The Guardian, retrieved June 12, 2012

- ^ R. Thelen (2008) Daily Star, Lebanon retrieved June 12, 2012

- ^ Martin, La Chaldée, 205–12

- ^ Chabot, 'Patriarcat chaldéen de Babylone', ROC, 1 (1898), 433–53

- ^ Tfinkdji, EC, 476–520; Wilmshurst, EOCE, 362

- ^ Wilmshurst, EOCE, 360–3

- ^ Rassam, H. (1897), Asshur and the Land of Nimrod London

- ^ Soane, E.B. To Mesopotamia and Kurdistan in Disguise John Murray: London, 1912 p. 92

- ^ Rev. W.A. Wigram (1929), The Assyrians and Their Neighbours London

- ^ Efram Yildiz's "The Assyrians" Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies, 13.1, pp. 22, ref 24

- ^ "The Eastern Christian Churches" by Ronald Roberson. "In 1552, when the new patriarch was elected, a group of Assyrian bishops refused to accept him and decided to seek union with Rome. They elected the reluctant abbot of a monastery, Yuhannan Sulaqa, as their own patriarch and sent him to Rome to arrange a union with the Catholic Church. In early 1553 Pope Julius III proclaimed him Patriarch Simon VIII "of the Chaldeans" and ordained him a bishop in St. Peter's Basilica on April 9, 1553

- ^ Aqaliyat shimal al-‘Araq; bayna al-qanoon wa al-siyasa" (Northern Iraq Minorities; between Law and Politics) by Dr. Jameel Meekha Shi’yooka

- ^ Nisan, M. 2002. Minorities in the Middle East: A History of Struggle for Self Expression .Jefferson: McFarland & Company. Jump up ^ http://www.upenn.edu/pennpress/book/14225.html

- ^ a b Travis, Hannibal. Genocide in the Middle East: The Ottoman Empire, Iraq, and Sudan. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 2010, 2007, pp. 237-77, 293–294 ISBN 9781594604362

- ^ 71.^ Jump up to: a b Parpola, Simo (2004). "National and Ethnic Identity in the Neo-Assyrian Empire and Assyrian Identity in Post-Empire Times" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies (JAAS) 18 (2): 22.

- ^ http://www.ishtartv.com/book,14,books.html

- ^ http://www.alsumaria.tv/mobile/news/51371/%D8%AD%D8%B1%D9%83%D8%A9-%D9%83%D9%84%D8%AF%D8%A7%D9%86%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D8%AA%D8%AD%D8%B0%D8%B1-%D9%85%D9%86-%D8%A3%D8%B2%D9%85%D8%A9-%D9%85%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D8%AE%D8%B7%D8%B1%D8%A9-%D8%A8%D8%B3%D8%A8/ar

- ^ http://www.iraqnla-iq.com/opac/fullrecr.php?nid=26280&hl=ara

- ^ http://solutions.cengage.com/gale/apps/

- ^ http://www.chaldeansonline.org/chaldean/

- ^ https://sites.google.com/site/chaldeanwriters/

- ^ http://www.kaldaya.net/2011/Articles/07_July2011/31_July25_BishopMarSarhadJamou.html

- ^ http://chaldeanflag.com/flag.html Chaldean Flag ... from A to Z

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)