Charcoal

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2010) |

Charcoal is a lightweight, black residue, consisting of carbon and any remaining ash, obtained by removing water and other volatile constituents from animal and vegetation substances. Charcoal is usually produced by slow pyrolysis, the heating of wood or other substances in the absence of oxygen (see char and biochar).

History

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2010) |

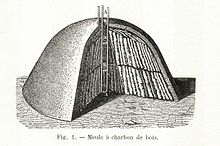

Historically, the production of wood charcoal in locations where there is an abundance of wood dates back to a very ancient period, and generally consists of piling billets of wood on their ends so as to form a conical pile, openings being left at the bottom to admit air, with a central shaft to serve as a flue. The whole pile is covered with turf or moistened clay. The firing is begun at the bottom of the flue, and gradually spreads outwards and upwards. The success of the operation depends upon the rate of the combustion. Under average conditions, 100 parts of wood yield about 60 parts by volume, or 25 parts by weight, of charcoal; small-scale production on the spot often yields only about 50%, while large-scale became efficient to about 90% even by the seventeenth century. The operation is so delicate that it was generally left to colliers (professional charcoal burners). They often lived alone in small huts in order to tend their wood piles. For example, in the Harz Mountains of Germany, charcoal burners lived in conical huts called Köten which are still much in evidence today[when?].

The massive production of charcoal (at its height employing hundreds of thousands, mainly in Alpine and neighbouring forests) was a major cause of deforestation, especially in Central Europe.[when?] In England, many woods were managed as coppices, which were cut and regrew cyclically, so that a steady supply of charcoal would be available (in principle) forever; complaints (as early as the Stuart period) about shortages may relate to the results of temporary over-exploitation or the impossibility of increasing production to match growing demand. The increasing scarcity of easily harvested wood was a major factor behind the switch to fossil fuel equivalents, mainly coal and brown coal for industrial use.

The modern process of carbonizing wood, either in small pieces or as sawdust in cast iron retorts, is extensively practiced where wood is scarce, and also for the recovery of valuable byproducts (wood spirit, pyroligneous acid, wood tar), which the process permits. The question of the temperature of the carbonization is important; according to J. Percy, wood becomes brown at 220 °C (428 °F), a deep brown-black after some time at 280 °C (536 °F), and an easily powdered mass at 310 °C (590 °F).[1] Charcoal made at 300 °C (572 °F) is brown, soft and friable, and readily inflames at 380 °C (716 °F); made at higher temperatures it is hard and brittle, and does not fire until heated to about 700 °C (1,292 °F).

In Finland and Scandinavia, the charcoal was considered the by-product of wood tar production. The best tar came from pine, thus pinewoods were cut down for tar pyrolysis. The residual charcoal was widely used as substitute for metallurgical coke in blast furnaces for smelting. Tar production led to rapid deforestation: it has been estimated all Finnish forests are younger than 300 years. The end of tar production at the end of the 19th century resulted in rapid re-forestation.

The charcoal briquette was first invented and patented by Ellsworth B. A. Zwoyer of Pennsylvania in 1897[2] and was produced by the Zwoyer Fuel Company. The process was further popularized by Henry Ford, who used wood and sawdust byproducts from automobile fabrication as a feedstock. Ford Charcoal went on to become the Kingsford Company.

Production methods

Charcoal has been made by various methods. The traditional method in Britain used a clamp. This is essentially a pile of wooden logs (e.g. seasoned oak) leaning against a chimney (logs are placed in a circle). The chimney consists of 4 wooden stakes held up by some rope. The logs are completely covered with soil and straw allowing no air to enter. It must be lit by introducing some burning fuel into the chimney; the logs burn very slowly and transform into charcoal in a period of 5 days' burning. If the soil covering gets torn (cracked) by the fire, additional soil is placed on the cracks. Once the burn is complete, the chimney is plugged to prevent air from entering.[3] The true art of this production method is in managing the sufficient generation of heat (by combusting part of the wood material), and its transfer to wood parts in the process of being carbonised. A strong disadvantage of this production method is the huge amount of emissions that are harmful to human health and the environment (emissions of unburnt methane).[4] As a result of the partial combustion of wood material, the efficiency of the traditional method is low.

Modern methods employ retorting technology, in which process heat is recovered from, and solely provided by, the combustion of gas released during carbonisation. (Illustration:[5]). Yields of retorting are considerably higher than those of kilning, and may reach 35%-40%.

The properties of the charcoal produced depend on the material charred. The charring temperature is also important. Charcoal contains varying amounts of hydrogen and oxygen as well as ash and other impurities that, together with the structure, determine the properties. The approximate composition of charcoal for gunpowders is sometimes empirically described as C7H4O. To obtain a coal with high purity, source material should be free of non-volatile compounds.

Types

- Common charcoal is made from peat, coal, wood, coconut shell, or petroleum.

- Sugar charcoal is obtained from the carbonization of sugar and is particularly pure. It is purified by boiling with acids to remove any mineral matter and is then burned for a long time in a current of chlorine in order to remove the last traces of hydrogen.[6] It was used by Henri Moissan in his early attempt to create synthetic diamonds.[citation needed]

- Activated charcoal is similar to common charcoal but is made especially for medical use. To produce activated charcoal, manufacturers heat common charcoal in the presence of a gas that causes the charcoal to develop many internal spaces or "pores." These pores help activated charcoal trap chemicals.

- Lump charcoal is a traditional charcoal made directly from hardwood material. It usually produces far less ash than briquettes.

- Japanese charcoal has had pyroligneous acid removed during the charcoal making; it therefore produces almost no smell or smoke when burned. The traditional charcoal of Japan is classified into two types:

- White charcoal (Binchōtan) is very hard and produces a metallic sound when struck.

- Black charcoal

- A more recent type is of factory-made briquettes:

- Pillow shaped briquettes are made by compressing charcoal, typically made from sawdust and other wood by-products, with a binder and other additives. The binder is usually starch. Briquettes may also include brown coal (heat source), mineral carbon (heat source), borax, sodium nitrate (ignition aid), limestone (ash-whitening agent), raw sawdust (ignition aid), and other additives.

- Hexagonal sawdust briquette charcoal is made by compressing sawdust without binders or additives. Hexagonal Sawdust Briquette Charcoal is the preferred charcoal in Taiwan, Korea, Greece, and the Middle East. It has a round hole through the center, with a hexagonal intersection. It is used primarily for barbecue as it produces no odor, no smoke, little ash, high heat, and long burning hours (exceeding 4 hours).

- Extruded charcoal is made by extruding either raw ground wood or carbonized wood into logs without the use of a binder. The heat and pressure of the extruding process hold the charcoal together. If the extrusion is made from raw wood material, the extruded logs are subsequently carbonized.

Uses

Charcoal has been used since earliest times for a large range of purposes including art and medicine, but by far its most important use has been as a metallurgical fuel. Charcoal is the traditional fuel of a blacksmith's forge and other applications where an intense heat is required. Charcoal was also used historically as a source of black pigment by grinding it up. In this form charcoal was important to early chemists and was a constituent of formulas for mixtures such as black powder. Due to its high surface area charcoal can be used as a filter, and as a catalyst or as an adsorbent.

Metallurgical fuel

Charcoal burns at intense temperatures, up to 2,700 °C (4,890 °F).[verification needed] By comparison the melting point of iron is approximately 1,200 to 1,550 °C (2,190 to 2,820 °F). Due to its porosity it is sensitive to the flow of air and the heat generated can be moderated by controlling the air flow to the fire. For this reason charcoal is still widely used by blacksmiths. Charcoal has been used for the production of iron since Roman times and steel in modern times where it also provided the necessary carbon. Charcoal briquettes can burn up to approximately 2300 °F (1,260 °C) with a forced air blower forges.

In the 16th century England had to pass laws to prevent the country from becoming completely denuded of trees due to production of iron. In the 19th century charcoal was largely replaced by coke, baked coal, in steel production due to cost.

Industrial fuel

Historically, charcoal was used in great quantities for smelting iron in bloomeries and later blast furnaces and finery forges. This use was replaced by coke in the 19th Century as part of the Industrial Revolution.

Cooking fuel

Prior to the industrial revolution charcoal was occasionally used as a cooking fuel. Modern "charcoal briquettes", widely used for outdoor cooking, are not charcoal though they may contain some.

Syngas production, automotive fuel

Like many other sources of carbon, charcoal can be used for the production of various syngas compositions; i.e., various CO + H2 + CO2 + N2 mixtures. The syngas is typically used as fuel, including automotive propulsion, or as a chemical feedstock.

In times of scarce petroleum, automobiles and even buses have been converted to burn wood gas (a gas mixture consisting primarily of diluting atmospheric nitrogen, but also containing combustible gasses, mostly carbon monoxide) released by burning charcoal or wood in a wood gas generator. In 1931 Tang Zhongming developed an automobile powered by charcoal, and these cars were popular in China until the 1950s and in occupied France during World War II (called gazogènes).[citation needed]

Carbon source

Charcoal may be used as a source of carbon in chemical reactions. One example of this is the production of carbon disulphide through the reaction of sulfur vapors with hot charcoal. In that case the wood should be charred at high temperature to reduce the residual amounts of hydrogen and oxygen that lead to side reactions.

Purification and filtration

Charcoal may be activated to increase its effectiveness as a filter. Activated charcoal readily adsorbs a wide range of organic compounds dissolved or suspended in gases and liquids. In certain industrial processes, such as the purification of sucrose from cane sugar, impurities cause an undesirable color, which can be removed with activated charcoal. It is also used to absorb odors and toxins in gases, such as air. Charcoal filters are also used in some types of gas masks. The medical use of activated charcoal is mainly the absorption of poisons.[7] Activated charcoal is available without a prescription, so it is used for a variety of health-related applications. For example, it is often used to reduce discomfort and embarrassment due to excessive gas (flatulence) in the digestive tract.[8]

Animal charcoal or bone black is the carbonaceous residue obtained by the dry distillation of bones. It contains only about 10% carbon, the remainder being calcium and magnesium phosphates (80%) and other inorganic material originally present in the bones. It is generally manufactured from the residues obtained in the glue and gelatin industries. Its decolorizing power was applied in 1812 by Derosne to the clarification of the syrups obtained in sugar refining; but its use in this direction has now greatly diminished, owing to the introduction of more active and easily managed reagents. It is still used to some extent in laboratory practice. The decolorizing power is not permanent, becoming lost after using for some time; it may be revived, however, by washing and reheating. Wood charcoal also to some extent removes coloring material from solutions, but animal charcoal is generally more effective.[citation needed]

Art

Charcoal is used in art for drawing, making rough sketches in painting and is one of the possible media for making a parsemage. It must usually be preserved by the application of a fixative. Artists generally utilize charcoal in three forms:

- Vine charcoal is created by burning sticks or vines.

- Powdered charcoal is often used to "tone" or cover large sections of a drawing surface. Drawing over the toned areas darkens it further, but the artist can also lighten (or completely erase) within the toned area to create lighter tones.

- Compressed charcoal charcoal powder mixed with gum binder compressed into round or square sticks. The amount of binder determines the hardness of the stick.[9] Compressed charcoal is used in charcoal pencils.

Horticulture

One additional use of charcoal was rediscovered recently in horticulture. Although American gardeners have been using charcoal for a short while, research on Terra preta soils in the Amazon has found the widespread use of biochar by pre-Columbian natives to turn unproductive soil into carbon rich soil. The technique may find modern application, both to improve soils and as a means of carbon sequestration.[10]

Medicine

Charcoal was consumed in the past as dietary supplement for gastric problems in the form of charcoal biscuits. Now it can be consumed in tablet, capsule or powder form, for digestive effects.[11] Research regarding its effectiveness is controversial.[12] To measure the mucociliary transport time the use was introduced by Passali in combination with saccharin.[13]

Red colobus monkeys in Africa have been observed eating charcoal for the purposes of self-medication. Their leafy diets contain high levels of cyanide, which may lead to indigestion. So they learned to consume charcoal, which absorbs the cyanide and relieves indigestion. This knowledge about supplementing their diet is transmitted from mother to infant.[14]

Environmental implications

The use of charcoal as a smelting fuel has been experiencing a resurgence in South America resulting in severe environmental, social and medical problems.[15][16]

Charcoal production at a sub-industrial level is one of the causes of deforestation. Charcoal production is now usually illegal and nearly always unregulated as in Brazil where charcoal production is a large illegal industry for making pig iron.[17][18][19]

Massive forest destruction has been documented in areas such as Virunga National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where it is considered a primary threat to the survival of the mountain gorillas.[20] Similar threats are found in Zambia.[21] In Malawi, illegal charcoal trade employs 92,800 workers and is the main source of heat and cooking fuel for 90 percent of the nation’s population.[22] Some experts, such as Duncan MacQueen, Principal Researcher–Forest Team, International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), argue that while illegal charcoal production causes deforestation, a regulated charcoal industry that required replanting and sustainable use of the forests "would give their people clean efficient energy – and their energy industries a strong competitive advantage."[22]

Degradation

The bacterium Diplococcus degrades charcoal, thereby raising its temperature.[23]

In popular culture

The last section of the film Le Quattro Volte (2010) gives a good and long, if poetic, documentation of the traditional method of making charcoal.[24] The Arthur Ransome children's series Swallows and Amazons (particularly the second book Swallowdale) features carefully drawn vignettes of the lives and the techniques of charcoal burners at the start of the 20th century, in the Lake District of the UK.

See also

- Binchōtan

- Biochar

- Biomass briquettes

- Char cloth

- Coke (fuel), made from coal rather than wood

- Pyrolysis

- Shichirin

- Slash-and-char

- Terra preta

- Tortillon

- Kingsford

- Wood gas

References

- ^ Chisolm, Hugh (1910). Encyclopaedia Britannica, Eleventh Edition, Volume V. New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Barbeque – History of Barbecue". Inventors.about.com. 2010-06-15. Retrieved 2011-12-28.

- ^ "Geoarch". Geoarch. 1999-05-31. Retrieved 2012-05-20.

- ^ "Roland.V. Siemons, Loek Baaijens, An Innovative Carbonisation Retort: Technology and Environmental Impact, TERMOTEHNIKA, 2012, XXXVIII, 2, 131‡138 131" (PDF).

- ^ "Kilning vs. Retorting: the cause of emissions of unburnt gases".

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 305–307.

- ^ Dawson, Andrew. "Activated charcoal: a spoonful of sugar". Australian Prescriber. NPS MedicineWise. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ^ "Treating flatulence". NHS. NHS UK. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- ^ "charcoal: powdered, compressed, willow and vine". Muse Art and Design. Muse Art and Design. 7 September 2011. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- ^ Johannes Lehmann, ed. (2009). Biochar for Environmental Management: Science and Technology. Stephen Joseph. Earthscan. ISBN 978-1-84407-658-1. Retrieved 30 Dec 2013.

- ^ Stearn, Margaret (2007). Warts and all: straight talking advice on life's embarrassing problems. London: Murdoch Books. p. 333. ISBN 978-1-921259-84-5. Retrieved 2009-05-03.

- ^ Am J Gastroenterology 2005 Feb 100(2)397–400 and 1999 Jan 94(1) 208-12

- ^ Passali, Desiderio (1984). "Experiences in the determination of nasal mucociliary transport time". Acta Otolaryngol. 97 (3–4): 319–23. PMID 6539042.

- ^ "Clever Monkeys: Monkeys and Medicinal Plants". PBS. Retrieved 2012-05-20.

- ^ Michael Smith; David Voreacos (January 21, 2007). "Brazil: Enslaved workers make charcoal used to make basic steel ingredient". Seattle Times. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- ^ M. Kato1, D. M. DeMarini, A. B. Carvalho, M. A. V. Rego, A. V. Andrade1, A. S. V. Bonfim and D. Loomis (2004). "World at work: Charcoal producing industries in northeastern Brazil". Retrieved 16 September 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "U.S. car manufacturers linked to Amazon destruction, slave labor". News.mongabay.com. Retrieved 2012-05-20.

- ^ Publication - May 11, 2012 (2012-05-11). "Driving Destruction in the Amazon | Greenpeace International". Greenpeace.org. Retrieved 2012-05-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ The documentary film The Charcoal People (2000) [1] shows in detail the deforestation in Brazil, the poverty of the laborers and their families, and the method of constructing and using a clamp for burning the wood.

- ^ "Virunga National Park". Gorilla.cd. Retrieved 2012-05-20.

- ^ "Living on Earth: Zambia's Vanishing Forests". Loe.org. 1994-03-04. Retrieved 2011-12-28.

- ^ a b "Is charcoal the key to sustainable energy consumption in Malawi?". UNEARTH News. July 2013. Retrieved 10 August 2013.[dead link]

- ^ M.C. Potter (May 1908). "Bateria as agents in the oxidation of amorphous carbon". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B, Containing Papers of a Biological Character. 80: 239–259.

- ^ "Le quattro volte (2010)". Retrieved 16 September 2012.

External links

Media related to Charcoal at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Charcoal at Wikimedia Commons- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Simple technologies for charcoal making

- "On Charcoal" by Peter J F Harris