Conscription in Argentina

Conscription in Argentina, also known as "colimba", was the compulsory military service that men between the ages of eighteen and twenty-one had to fulfill in Argentina from 1901 to 1994.

History[edit]

Riccheri Law[edit]

In 1901, the Minister of War, Lieutenant General Pablo Riccheri, presented the project according to which Argentinian males in their twenties were recruited into the Armed Forces to serve for two years.

The aim of the project was to spread the idea of citizenship and equality before the law and to "literate" and integrate the children of immigrants, as well as to increase patriotism in men from different social classes and corners of the country. The project followed the ideals of the then President Julio Argentino Roca, also a military man, commander of the conquest of the Desert.

Law No. 4031 was approved by the Senate on December 11, 1901, after half a year of discussions.[1][2]

Origin of the term "colimba"[edit]

The term "colimba" derives from the vesre "colimi", itself derived from the word "milico" (slang for "military" or "soldier"). Originally, it consisted of serving in the daily activities of each branch, be it the navy, the air force or the army, where they were militarily trained. Another possible etymology, quite widespread, postulates that "colimba" derives from the first syllables of the words "Corra, limpie and barra" (run, clean and sweep), an ironic allusion to the main occupations of conscripts.[3]

Conscription system in the 1970s[edit]

In the 1970s, a numerical draw of lots was implemented, which was used to assign males over the age of eighteen who were to be conscripts to one of the three forces, according to the last three numbers of their national identity card.[4][5]

Involvement in conflicts[edit]

La Patagonia Rebelde[edit]

At the beginning of 1921, conscripts were sent together with the troops of the 10th Cavalry Regiment "Húsares de Pueyrredón" under the command of Lieutenant General Héctor Benigno Varela to put an end to a rural workers' strike in the national territory of Santa Cruz. On this occasion, the troops did not act and brought about the cessation of the strike with the promise that the conditions demanded by the strikers would be met. However, in October of the same year, a strike was again declared in rural areas. Army troops were again sent to Santa Cruz, where they put a stop to the strike by mass murdering strikers and people suspected of being strikers. In November, more troops were sent, mainly conscripts, under the command of Captain Elbio Anaya of the 2nd Cavalry Regiment "Lanceros de Paz".[6][7]

In total, more than 120 conscripts took part in the repression of the strike, in which an undetermined number of workers were killed, with estimates ranging from 1000 to 1500 dead. The conscripts were accused of carrying out a large part of these murders, as well as the theft of money, belongings and horses from the victims. [8][6] These events were popularly known as La Patagonia Trágica, after the book of the same name by José María Borrero and the four volumes by Osvaldo Bayer, entitled "Los vengadores de la Patagonia trágica" (The Avengers of Tragic Patagonia). However, they are better known as "La Patagoina Rebelde" after Héctor Olivera's 1974 film of the same name.

Falkland Islands War[edit]

Background[edit]

On 2 April 1982, the military junta led by Lieutenant General Leopoldo Fortunato Galtieri decided on the military occupation of the Falkland Islands, Georgias and South Sandwich Islands through Operation Rosario, after continuous inconclusive diplomatic claims and before the 150th anniversary of British usurpation, as well as in an attempt to take pressure off the civil-military dictatorship. The week before, two people were killed in the repression of anti-coup demonstrations; then the Plaza de Mayo itself was filled with demonstrators in favour of territorial resettling.

The Argentine military did not believe in an eventual British reconquest operation, since that country was going through its worst political and economic moment, and the United States, through its foreign minister, had suggested non-intervention because the memory of the Vietnam War was still fresh. Thus, the international context seemed to favour the Argentine position. However, with the operation already underway, US President Reagan called his Argentine counterpart and was clear: the United States did not support Argentina's territorial recomposition, which it saw as a big mistake, and would support its strategic ally, Britain. Galtieri had already played his card: on 2 April 1982, under the name of Operation Rosario, the Argentine armed forces recaptured the islands without causing British military or civilian casualties. Conscript soldiers between the ages of eighteen and twenty-one made up the combat units of the three Argentine Armed Forces deployed in the theatre of operations. Some thought the occupation would be brief and international pressure would lead to a diplomatic resolution favourable to Argentina; Thatcher and Galtieri, two questionable leaders with bad press, thought different.[9][10][11]

Conscripted deaths during the war[edit]

In the 74 days that the conflict lasted, 649 Argentine military personnel lost their lives, almost half of them in the sinking of the Belgrano. Of the total, 273 were conscripts.[12]

The units were made up of conscript born in the years 1962 and 1963, year 1962 had completed their training and had largely been discharged, and year 1963 had completed their basic period. Although the device was defensive, they also integrated patrols that developed missions such as in the exploration sections or in the Güemes Combat Team, which alerted the British landing and fought in San Carlos and then was heliborne to Darwin-Goose Beach (among other combat situations).

Torture and crimes against humanity during the war[edit]

During the war, various crimes against humanity were committed against conscript soldiers, including torture by officers. Conditions on the battlefield were marginal: conscripts had less than four months of training, went hungry and lacked the necessary shelter for the weather. Conscripts even went so far as to kill poultry, sheep and scavenge dumpsters for food.[13][14][15]

Over the years and in the aftermath of the war, the suicide rate of war veterans almost equalled the number of those killed in combat. In December 2018, the complaint of torture was published, the names of the prosecuted officers and it was announced that the trials will take place in the Province of Tierra del Fuego, Antarctica and South Atlantic Islands: 95 military officers have been prosecuted and 105 acts have been reported.[16]

Although the torture was well known in Argentine society, it was only in 2007 that the allegations against the officers were made public. In 2019, the trials against the officers prosecuted for crimes against humanity began in Ushuaia, with the indictment of 18 accused officers.[17][18]

Other participations[edit]

Conscripts were used as an action force in the six coups d'état that the country experienced. They also carried out tasks during these de facto governments, playing an active role in State Terrorism.

In 1955, there was a break in ideology within the Armed Forces, known as the division between the "Blue and Reds", which lasted until 1963, in which conscripts were aligned according to orders from their superiors.[19][20][21] In 1978, conscript soldiers were deployed along the border with Chile in Operation Soberanía.

Cease[edit]

Return to democracy[edit]

After the return to democracy in 1983 and the beginning of the trials of military juntas for crimes committed during the last dictatorship, the carapintadas uprisings took place, which, together with the economic hyperinflation during the government of Raúl Alfonsín, showed military service as a waste of money and an institution that undermined democracy.

Death of conscript Carrasco[edit]

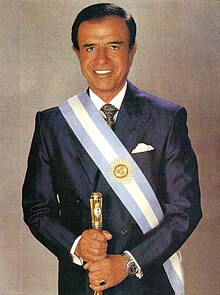

In 1994, conscript Omar Carrasco, who was serving in the 161st Artillery Group of the Argentine Army, was disappeared. His body was found a month later in the barracks. When it was discovered and publicised that Carrasco had been a victim of torture, the institution was widely criticised and, in response, then President Carlos Menem put an end to compulsory military service in Argentina on 31 August 1994.[22]

Proposal for reactivation[edit]

In 2007[edit]

In 2007, former provincial senator Alfredo Olmedo proposed the reactivation of compulsory military service, which he called "community military service". His project was aimed at recruiting young people who neither studied nor worked. The proposal was considered a step backwards for democracy and was criticised by the media and the community at large, although a minority showed interest in the return of the "colimba".

In 2019[edit]

In 2019, the government of Mauricio Macri created the "Voluntary Civic Service in Values" under the decree resolution 2019-598-APN-MSG, which stated the need to educate people who did not work or study, in a voluntary civic service to train them in trades and new technologies, thus squaring a relaunch of the old service, with a different purpose but for the same reasons as the Riccheri Law.[23]

In popular culture[edit]

- 1963: Canuto Cañete, conscripto del 7; comedy film with Carlitos Balá.

- 1972: La colimba no es la guerra; comic film by director Jorge Mobaied about the Argentinean military service.

- 1984: Los chicos de la guerra; dramatic film by director Bebe Kamin about the experiences of three conscript boys from different social groups who are sent to the Malvinas War and the consequences that each one suffers after the war.

- 1986: Los colimbas se divierten; first film of the comic trilogy by director Enrique Carreras set in the Argentinean military service starring Alberto Olmedo and Jorge Porcel.

- 1986: Rambito y Rambón, primera misión; second film of the comic trilogy by director Enrique Carreras set in the Argentinean military service starring Alberto Olmedo and Jorge Porcel.

- 1987: Los colimbas al ataque; third film of the comic trilogy by director Enrique Carreras set in the Argentinean military service starring Alberto Olmedo and Jorge Porcel.

- 1997: La carta perdida; song by singer Soledad Pastorutti about a real letter written by a conscripted soldier in the Malvinas War to his mother.

- 1997: Bajo bandera; dramatic film directed by Juan José Jusid based on the Carrasco Case.

- 2005: Iluminados por el fuego; dramatic film by director Tristán Bauer which depicts a story of conscripts in the Malvinas War. The film won the Goya Award for best film and received harsh criticism from ex-combatants, who claimed that the film did not represent them, as it was largely based on the opinion of an ex-combatant who committed acts of cowardice in the war, putting the lives of his comrades at risk.

- 2017: Soldado argentino solo conocido por Dios; dramatic film by director Rodrigo Fernández Engler based on several stories, which tell the story of several conscripted soldiers in various scenarios of the Falklands War.

Famous conscripts[edit]

Some famous conscripts included:

- Osvaldo Bayer, historian.

- Zeta Bosio, bassist of Soda Stereo.

- Gustavo Cerati, vocalist and guitarist of Soda Stereo.

- Jorge Cafrune, folklorist.

- Roberto De Vicenzo, golfer.

- Sergio Denis, musician.

- Osvaldo Escudero, footballer.

- Baby Etchecopar, journalist.

- Luis Franco, writer.

- Charly García, musician.

- Rodolfo García, musician.

- Diego Maradona, footballer.

- Quino, cartoonist.

- Agustín Tosco, trade unionist.

- Alejandro Dolina, broadcaster, writer and musician.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ NorteOnline (2022-05-04). "Breve historia del Servicio Militar argentino, el obligatorio y el voluntario". NorteOnline (in Spanish). Retrieved 2024-07-01.

- ^ Parise, Eduardo (2016-12-05). "La "no guerra" que llevó a instrumentar la colimba". Clarín (in Spanish). Retrieved 2024-07-01.

- ^ "DICCIONARIO ARGENTINO ~ ESPAÑOL | Castellano - La Página del Idioma Español = El Castellano - Etimología - Lengua española". www.elcastellano.org. Retrieved 2024-07-01.

- ^ Soprano, Germán (2016). "Ciudadanos y soldados en el debate de la Ley sobre el Servicio Militar Voluntario en la Argentina democrática". Prohistoria. 25: 105–133. ISSN 1851-9504.

- ^ "Argentina.gob.ar". Argentina.gob.ar (in Spanish). Retrieved 2024-07-01.

- ^ a b Hacer, Todo Por (2018-12-25). "[Ensayo] La Patagonia Rebelde". Todo Por Hacer (in Spanish). Retrieved 2024-07-01.

- ^ "La Secretaría de Derechos Humanos pidió que se investigue la masacre de la "Patagonia rebelde" como crímenes de lesa humanidad y tenga un juicio por la verdad". Argentina.gob.ar (in Spanish). 2022-12-07. Retrieved 2024-07-01.

- ^ "Cómo se enriquecieron los dueños de La Anónima: matanzas y abusos contra los pueblos originarios - El Extremo Sur". www.elextremosur.com (in Spanish). 2021-02-09. Retrieved 2024-07-01.

- ^ "Argentina's dictatorship dug its own grave in Falklands War". France 24. 2022-03-30. Retrieved 2024-07-01.

- ^ Jenkins, Simon (2012-04-01). "Falklands war 30 years on and how it turned Thatcher into a world celebrity". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2024-07-01.

- ^ "A Short History of the Falklands Conflict". Imperial War Museums. Retrieved 2024-07-01.

- ^ "Malvinas - Ex Combatientes - Lista de muertos y desaparecidos en acción". www.cescem.org.ar. Retrieved 2024-07-01.

- ^ "Torturas en Malvinas: el entramado oculto de antisemitismo, estaqueos y hambre". Perfil (in Spanish). 2018-04-02. Retrieved 2024-07-01.

- ^ Día, Hurlingham al (2017-03-31). "Una guerra contra el frío, contra el hambre, contra los ingleses y contra nosotros mismos". Hurlingham Al Día (in Spanish). Retrieved 2024-07-01.

- ^ "Página/12 :: El país :: Frío y hambre en las islas". www.pagina12.com.ar (in Spanish). Retrieved 2024-07-01.

- ^ Clarín, Redacción (2018-12-07). "Revelan los nombres de los militares acusados de torturar a soldados en Malvinas". Clarín (in Spanish). Retrieved 2024-07-01.

- ^ "Juicio por delitos de lesa humanidad durante la guerra de Malvinas". www.elpatagonico.com. Retrieved 2024-07-01.

- ^ "Repudio ante la demora de juicio por torturas a soldados de Malvinas | Agencia Paco Urondo". www.agenciapacourondo.com.ar. Retrieved 2024-07-01.

- ^ "Historia. Cuando los militares se enfrentaron en Azules y Colorados". La Izquierda Diario - Red internacional (in Spanish). Retrieved 2024-07-01.

- ^ Yofre, Por Juan Bautista Tata (2024-04-14). "Azules y Colorados: el enfrentamiento entre las Fuerzas Armadas que tiñó de sangre la década del '60 y encumbró a Onganía". infobae (in European Spanish). Retrieved 2024-07-01.

- ^ Clarín, Redacción (2003-04-02). "El otro 2 de abril: la batalla en el Ejército entre Azules y Colorados". Clarín (in Spanish). Retrieved 2024-07-01.

- ^ de 2020, Por Eduardo AnguitaDaniel Cecchini20 de Enero. ""Corre, limpia y baila": por qué el asesinato del soldado Omar Carrasco terminó con la brutal práctica". infobae (in European Spanish). Retrieved 28 August 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ El Gobierno creó el "Servicio Cívico Voluntario en Valores" dirigido a jóvenes de 16 a 20 años, Diario Perfil, 20 de julio de 2019