Durian

| Durian | |

|---|---|

| |

| Durio kutejensis fruits, also known as durian merah | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Division: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Durio |

| Species | |

|

There are currently 30 recognised species (see text) | |

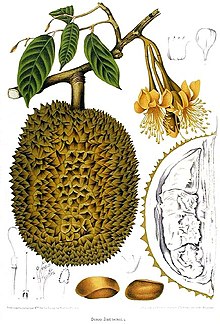

The durian (IPA: [d̪uˈɾi.ɑn]) is the fruit of trees of the genus Durio belonging to the Malvaceae, a large family which includes hibiscus, okra, cotton, mallows and linden trees. Widely known and revered in Southeast Asia as the "King of Fruits,"[1] the fruit is distinctive for its large size, unique odour, and a formidable thorn-covered husk. Its name comes from the Malay word duri (thorn) together with Malay suffix that is -an (for building a noun in Malay), meaning "thorny fruit."[2][3]

There are 30 recognised Durio species, all native to Southeast Asia and at least nine of which produce edible fruit.[4] Durio zibethinus is the only species available in the international market; other species are sold in their local region.

The fruit can grow up to 30 centimetres (12 in) long and 15 centimetres (6 in) in diameter,[5][6] and typically weighs one to three kilograms (2 to 7 lbs).[5] Its shape ranges from oblong to round, the colour of its husk green to brown and its flesh pale-yellow to red, depending on species.[5] The hard outer husk is covered with sharp, prickly thorns, while the edible custard-like flesh within emits the strong, distinctive odour, which is regarded as either fragrant or overpowering and offensive. The taste of the flesh has been described as nutty and sweet.

Species

- For the complete list of known species of Durio, see List of Durio species.

Durian trees are relatively large, growing up to 25–50 metres (80–165 ft) in height, depending on species. The leaves are evergreen, opposite, elliptic to oblong and 10–18 centimetres (4–7 in) long. The flowers are produced in three to thirty clusters together on large branches and the trunk, each flower having a calyx (sepals) and 5 (rarely 4 or 6) petals. Durian trees have one or two flowering and fruiting periods each year, although the timing of these varies depending on species, cultivars and localities. A typical durian tree can bear fruit after four or five years. The durian fruit, which can hang from any branch, matures in about three months after pollination. Among the thirty known species of Durio, so far nine species have been identified to produce edible fruits: D. zibethinus, D. dulcis, D. grandiflorus, D. graveolens, D. kutejensis, D. lowianus, D. macrantha, D. oxleyanus and D. testudinarum. However, there are many species for which the fruit has never been collected or properly examined, and other species with edible fruit may exist.[5]

D. zibethinus is the only species commercially cultivated on a large scale and available outside of its native region. Since this species is open-pollinated, it shows considerable diversity in fruit colour and odour, size of flesh and seed, and tree phenology. In the species name, zibethinus refers to the Indian civet, Viverra zibetha. There is disagreement regarding whether this name, bestowed by Linnaeus, refers to civets being so fond of the durian that the fruit was used as bait to entrap them, or to the durian smelling like the civet.[7]

Durian flowers are large and feathery with copious nectar, and give off a heavy, sour and buttery odour. These features are typical of flowers which are pollinated by certain species of bats while they eat nectar and pollen.[8] According to a research conducted in Malaysia during 1970s, durians were pollinated almost exclusively by cave fruit bats (Eonycteris spelaea).[5] However, a more recent research done in 1996 indicated that two species, D. grandiflorus and D. oblongus, were pollinated by spiderhunters (Nectariniidae) and that the other species, D. kutejensis, was pollinated by giant honey bees and birds as well as bats.[9]

Cultivars

Numerous cultivars (also called "clones") of durian have arisen in southeastern Asia over the centuries. They used to be grown from seeds with superior quality, but are now propagated by layering, marcotting, or more commonly, by grafting, including bud, veneer, wedge, whip or U-grafting onto seedlings of random rootstocks. Different cultivars can be distinguished to some extent by variations in the fruit shape, such as the shape of the spines.[5] Durian consumers do express preferences for specific cultivars, which fetch higher prices in the market.[10]

Most cultivars have both a common name and also a code number starting with "D". For example, some popular clones are Kop (D99), Chanee (D123), Tuan Mek Hijau (D145), Kan Yao (D158), Mon Thong (D159), Kradum Thong, and with no common name, D24. Each cultivar has a distinct taste and odour. More than 200 cultivars of D. zibethinus exist in Thailand, Chanee being the most preferred rootstock due to its resistance to infection by Phytophthora palmivora. Among all the cultivars in Thailand, though, only four see large scale commercial cultivation: Chanee, Kradum Thong, Mon Thong, and Kan Yao. There are more than 100 registered cultivars in Malaysia and many superior cultivars have been identified through competitions held at the annual Malaysian Agriculture, Horticulture and Agrotourism Show. In Vietnam, the same process has been done through competitions held by the Southern Fruit Research Institute.

In recent times, Songpol Somsri, a Thai government scientist, crossbred more than ninety varieties of durian to create Chantaburi No. 1, a cultivar without the characteristic odour, which is awaiting final approval from the local Ministry of Agriculture.[11] Another hybrid he created, named Chantaburi No. 3, develops the odour about three days after the fruit is picked, which enables an odourless transport and satisfies consumers who prefer the pungent odour.[11]

Availability

The durian is native to Indonesia, Malaysia, and Brunei. There is some debate as to whether the durian is native to the Philippines, or has been introduced.[5] The durian is grown in areas with a similar climate; it is strictly tropical and stops growing when mean daily temperatures drop below 22°C (71°F).[4]

The centre of ecological diversity for durians is the island of Borneo, where the fruit of the edible species of Durio including D. zibethinus, D. dulcis, D. graveolens, D. kutejensis, D. oxleyanus and D. testudinarium are sold in local markets. In Brunei, D. zibethinus is not grown because consumers prefer other species such as D. graveolens, D. kutejensis and D. oxyleyanus. These species are commonly distributed in Brunei and together with other species like D. testudinarium and D. dulcis, represent rich genetic diversity.[12] In the Philippines, the centre of durian production is the Davao Region. The Kadayawan festival is an annual celebration featuring the durian in Davao City.

Although the durian is not native to Thailand, the country is currently one of the major exporters of durians, growing 781,000 tonnes (860,000 S/T) of the world's total harvest of 1,400,000 tonnes (1,540,000 S/T) in 1999, exporting 111,000 tonnes (122,000 S/T).[13] Malaysia and Indonesia followed, both producing about 265,000 tonnes (292,000 S/T) each. Malaysia exported 35,000 tonnes (38,600 S/T) in 1999.[13] Other places where durians are grown include Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, Myanmar, India, Sri Lanka, West Indies, Florida, Hawaii, Papua New Guinea, Polynesian Islands, Madagascar, southern China (Hainan Island), northern Australia.

Durian was introduced into Australia in the early 1960s and clonal material was first introduced in 1975. Over thirty clones of D. zibethinus and six Durio species have been subsequently introduced into Australia.[14] China is the major importer, purchasing 65,000 tonnes (72,000 S/T) in 1999, followed by Singapore with 40,000 tonnes (44,000 S/T) and Taiwan with 5,000 tonnes (5,500 S/T). In the same year, the United States imported 2,000 tonnes (2,200 S/T), mostly frozen, and the European Community imported 500 tonnes (550 S/T).[13] In season durians can be found in mainstream Japanese supermarkets while, in the West, they are sold mainly by Asian markets.

Flavour and odour

Writing in 1856, the British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace provides a much-quoted description of the flavour of the durian:

A rich custard highly flavoured with almonds gives the best general idea of it, but there are occasional wafts of flavour that call to mind cream-cheese, onion-sauce, sherry-wine, and other incongruous dishes. Then there is a rich glutinous smoothness in the pulp which nothing else possesses, but which adds to its delicacy.[15]

Wallace cautions that "the smell of the ripe fruit is certainly at first disagreeable"; more recent descriptions by westerners can be more graphic. Travel and food writer Richard Sterling says:

... its odor is best described as pig-shit, turpentine and onions, garnished with a gym sock. It can be smelled from yards away. Despite its great local popularity, the raw fruit is forbidden from some establishments such as hotels, subways and airports, including public transportation in Southeast Asia.[16]

The unusual odour has prompted many people to search for an accurate description. Comparisons have been made with the civet, sewage, stale vomit, skunk spray, and used surgical swabs.[17] The wide range of descriptions for the odour of durian may have a great deal to do with the wide variability of durian odour itself. Durians from different species or clones can have significantly different aromas; for example, red durian (D. dulcis) has a deep caramel flavour with a turpentine odour, while red-fleshed durian (D. graveolens) emits a fragrance of roasted almonds.[18] The degree of ripeness has a great effect on the flavour as well.[5] Three scientific analyses of the composition of durian aroma — from 1972, 1980, and 1995 — each found a different mix of volatile compounds, including esters, ketones and many different organosulfur compounds, with no agreement on which may be primarily responsible for the distinctive odour.[5]

This strong odour can be detected half a mile away by animals, thus luring them. In addition, the fruit is extremely appetising to a variety of animals, from squirrels to mouse deer, pigs, orangutan, elephants, and even carnivorous tigers. While some of these animals eat the fruit and dispose of the seed under the parent plant, others swallow the seed with the fruit and then transport it some distance before excreting, with the seed being dispersed as the result.[19] The thorny armored covering of the fruit may have evolved because it discourages smaller animals, since larger animals are more likely to transport the seeds far from the parent tree.[20]

Ripeness and selection

According to Larousse Gastronomique, the durian fruit is ready to eat when its husk begins to crack.[21] However, the ideal stage of ripeness to be enjoyed varies from region to region in Southeast Asia and also by species. Some species grow so tall, they can only be collected once they have fallen to the ground, whereas most cultivars of D. zibethinus (such as Mon Thong) are nearly always cut from the tree and allowed to ripen while waiting to be sold. Some people in southern Thailand prefer their durians relatively young, when the clusters of fruit within the shell are still crisp in texture and mild in flavour. In northern Thailand, the preference is for the fruit to be as soft and pungent in aroma as possible. In Malaysia and Singapore, most consumers also prefer the fruit to be quite ripe and may even risk allowing the fruit to continue ripening after its husk has already cracked open on its own. In this state, the flesh becomes richly creamy, slightly alcoholic,[17] the aroma pronounced and the flavour highly complex.

The differing preferences regarding ripeness among different consumers makes it hard to issue general statements about choosing a "good" durian. A durian that falls off the tree continues to ripen for two to four days, but after five or six days most would consider it overripe and unpalatable.[6] The usual advice for a durian consumer choosing a whole fruit in the market is to examine the quality of the stem or stalk, which loses moisture as it ages: a big, solid stem is a sign of freshness.[22] Reportedly, unscrupulous merchants wrap, paint, or remove the stalks altogether. Another frequent piece of advice is to shake the fruit and listen for the sound of the seeds moving within, indicating that the durian is very ripe, and the pulp has dried out somewhat.[22]

History

The durian has been known and consumed in southeastern Asia since prehistoric times, but has only been known to the western world for about 600 years. The earliest known European reference on the durian is the record of Nicolo Conti who travelled to southeastern Asia in 15th century.[5] Garcia de Orta described durians in Colóquios dos Simples e Drogas da India published in 1563. In 1741, Herbarium Amboinense by the German botanist Georg Eberhard Rumphius was published, providing the most detailed and accurate account of durians for over a century. The genus Durio has a complex taxonomy that has seen the subtraction and addition of many species since it was created by Rumphius.[4] During the early stages of its taxonomical study, there was some confusion between durian and the soursop (Annona muricata), for both of these species had thorny green fruit.[5] It is also interesting to note the Malay name for the soursop is durian Belanda, meaning Dutch durian.[23] In 18th century, Weinmann considered the durian to belong to Castaneae as its fruit was similar to the horse chestnut.

D. zibethinus was introduced into Ceylon by the Portuguese in the 16th century and was reintroduced many times later. It has been planted in the Americas but confined to botanical gardens. The first seedlings were sent from Kew Botanic Gardens of England, to St. Aromen of Dominica in 1884.[24] The durian has been cultivated for centuries at the village level, probably since the late 18th century, and commercially in south-eastern Asia since the mid 20th century.[5] In his book My Tropic Isle, E. J. Banfield tells how, in the early 20th century, a Singapore friend sent him a durian seed which he planted and cared for on his tropical island off the north coast of Queensland.[25]

In 1949, the British botanist E. J. H. Corner published The Durian Theory or the Origin of the Modern Tree. His idea was that endozoochory (the enticement of animals to transport seeds in their stomach) arose before any other method of seed dispersal, and that primitive ancestors of Durio species were the earliest practitioners of that strategy, especially the red durian fruit exemplifying the primitive fruit of flowering plants.

Since the early 1990s, the domestic and international demand for durian in the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN) region has increased dramatically, partly due to the increasing affluence in Asia.[5]

Uses

Culinary

Durian fruit is used to flavour a wide variety of sweet edibles such as traditional Malay candy, ice kachang, dodol, rose biscuits, and, with a touch of modern innovation, ice cream, milkshakes, mooncakes, Yule logs and cappuccino. Pulut Durian is glutinous rice steamed with coconut milk and served with ripened durian. In Sabah, red durian is fried with onions and chilli and served as a side dish.[26] Red-fleshed durian is traditionally added to sajur, an Indonesian soup made from fresh water fish.[1] Tempoyak refers to fermented durian, usually made from lower quality durian that is unsuitable for direct consumption.[27] Tempoyak can be eaten either cooked or uncooked, is normally eaten with rice, and can also be used for making curry. Sambal Tempoyak is a Sumatran dish made from the fermented durian fruit, coconut milk, and a collection of spicy ingredients known as sambal.

In Thailand, blocks of durian paste are sold in the markets, though much of the paste is adulterated with pumpkin.[6] Unripe durians may be cooked as vegetable, except in the Philippines, where all uses are sweet rather than savoury. Malaysians make both sugared and salted preserves from durian. When durian is minced with salt, onions and vinegar, it is called boder. The durian seeds, which are the size of chestnuts, can be eaten whether they are boiled, roasted or fried in coconut oil, with a texture that is similar to taro or yam, but stickier. In Java, the seeds are sliced thin and cooked with sugar as a confectionery. Uncooked durian seeds are toxic due to cyclopropene fatty acids and should not be ingested.[28] Young leaves and shoots of the durian are occasionally cooked as greens. Sometimes the ash of the burned rind is added to special cakes.[6] The petals of durian flowers are eaten in the Batak provinces of Indonesia, while in the Moluccas islands the husk of the durian fruit is used as fuel to smoke fish. The nectar and pollen of the durian flower that honeybees collect is an important honey source, but the characteristics of the honey are unknown.[29]

Nutritional and medicinal

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 615 kJ (147 kcal) | ||||||||||||||||

27.09 g | |||||||||||||||||

| Dietary fiber | 3.8 g | ||||||||||||||||

5.33 g | |||||||||||||||||

1.47 g | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Other constituents | Quantity | ||||||||||||||||

| Water | 65g | ||||||||||||||||

Nutrient values are for edible portion, raw or frozen. Refuse: 68% (Shell and seeds) Source: USDA Nutrient database[30] | |||||||||||||||||

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[31] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[32] | |||||||||||||||||

Durian fruit contains a high amount of sugar,[20] vitamin C, potassium, and the serotoninergic amino acid tryptophan,[33] and is a good source of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats.[1][24] It is recommended as a good source of raw fats by several raw food advocates,[34][35] while others classify it as a high-glycemic or high-fat food, recommending to minimise its consumption.[36][37]

In Malaysia, a decoction of the leaves and roots used to be prescribed as an antipyretic. The leaf juice is applied on the head of a fever patient.[6] The most complete description of the medicinal use of the durian as remedies for fevers is a Malay prescription, collected by Burkill and Haniff in 1930. It instructs the reader to boil the roots of Hibiscus rosa-sinensis with the roots of Durio zibethinus, Nephelium longan, Nephelium mutabile and Artocarpus integrifolia, and drink the decoction or use it as a poultice.[38]

In 1920s, Durian Fruit Products, Inc., of New York City launched a product called "Dur-India" as a health food supplement, selling at US$9 for a dozen bottles, each containing 63 tablets. The tablets allegedly contained durian and a species of the genus Allium from India and vitamin E. The company promoted the supplement saying that they provide "more concentrated healthful energy in food form than any other product the world affords".[6]

Durian customs

Southeast Asian folk beliefs, as well as traditional Chinese medicine, consider the durian fruit to have warming properties liable to cause excessive sweating.[39] The traditional method to counteract this is to pour water into the empty shell of the fruit after the pulp has been consumed, and drink it.[17] An alternative method is to eat the durian in accompaniment with mangosteen that is considered to have cooling properties. People with high blood pressure or pregnant women are traditionally advised not to consume durian.[11][40]

Another common local belief is that the durian is harmful when eaten along with coffee[17] or alcoholic beverages.[5] The latter belief can be traced back at least to 18th century when Rumphius declared that one should not drink alcohol after eating durians as it will cause indigestion and bad breath. J. D. Gimlette stated in his Malay Poisons and Charm Cures (1929) that it was said that the durian fruit must not be eaten with brandy. In 1981, J. R. Croft wrote in his Bombacaceae: In Handbooks of the Flora of Papua New Guinea that a feeling of morbidity often follows the consumption of alcohol too soon after eating durian. Several medical investigations on the validity of this belief have been conducted, with varying conclusions.[5]

The Javanese believe durian to have aphrodisiac qualities, and impose a strict set of rules on what may or may not be consumed with the durian or shortly after.[17] The warnings against the supposed lecherous quality of this fruit soon spread to the West. The Swedenborgian mystic Herman Vetterling was particularly harsh on durian:

These erotomaniacs remind us of the Durian-eating Malays, who, because of the erotic properties of this fruit, become savage against anybody or anything that stands in their way of obtaining it. Fraser writes that upon eating it, men, monkeys, and birds 'are all aflame with erotic fire.' It is a blessing that this fruit is not obtainable in the West, because our store of sexual lunatics is already full to overflowing. We might perish in the foulest of mucks.[41]

A durian falling on a person's head can cause serious injuries or death because it is heavy and armed with sharp thorns, and may fall from a significant height, so wearing a hardhat is recommended when collecting the fruit. However, there are actually few reports of people getting hurt from falling durians. A saying in Indonesian, ketiban durian runtuh, which translates to "getting a fallen durian", means receiving an unexpected luck or fortune.[42] A naturally spineless variety of durian growing wild in Davao, Philippines was discovered in 1960s, and fruits borne on trees grown from seeds of this fruit were also spineless.[5] Sometimes spineless durians are produced artificially by scraping scales off the immature fruits, since the bases of the scales develop into the spines as the fruits mature.[5]

Cultural influence

The durian is commonly known as the "king of the fruits", a label that can be attributed to its formidable look and overpowering odour.[43] Due to its unusual characteristics, the durian has been referenced or parodied in various cultural mediums. To foreigners the durian is often perceived as a symbol of revulsion, as it can be seen in Dodoria, one of the villains in the Japanese anime Dragon Ball Z. Dodoria, whose name has been derived from the durian,[44] was given an unattractive appearance and a sinister role which required slaughtering numerous characters. In the Castlevania videogame series, "Rotten Durian" is an item that removes 500 HP from the character if consumed; its in-game description reads "Has introduced you to a whole new world of unpleasant odors."

In its native southeastern Asia, however, the durian is an everyday food and portrayed in the local media in accordance with the different cultural perception it has in the region. The durian symbolised the subjective nature of ugliness and beauty in Hong Kong director Fruit Chan's 2000 film Durian Durian (榴槤飄飄, Liulian piao piao), and was a nickname for the reckless but lovable protagonist of the eponymous Singaporean TV comedy Durian King played by Adrian Pang. Likewise, the oddly shaped Esplanade building in Singapore is often called "The Durian" by locals, although its design was not based on the fruit.

One of the names Thailand contributed to the list of storm names for Western North Pacific tropical cyclones was 'Durian',[45] which was retired after the second storm of this name in 2006. Being a fruit much loved by a variety of wild beasts, the durian sometimes signifies the long-forgotten animalistic aspect of humans, as in the legend of Orang Mawas, the Malaysian version of Bigfoot, and Orang Pendek, its Sumatran version, both of which have been claimed to feast on durians.[46][47]

Notes

- ^ a b c Heaton, Donald D. (2006). A Consumers Guide on World Fruit. BookSurge Publishing. pp. p. 54-56. ISBN 1419639552.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 1897.

Via durion, the Malay name for the plant.

- ^ Huxley, A. (Ed.) (1992). New RHS Dictionary of Gardening. Macmillan. ISBN 1-56159-001-0.

- ^ a b c O'Gara, E., Guest, D. I. and Hassan, N. M. (2004). "8.1 Botany and Production of Durian (Durio zibethinus) in Southeast Asia" (PDF). Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR). Retrieved 2006-03-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Brown, Michael J. (1997). Durio — A Bibliographic Review (PDF). International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRI). ISBN 92-9043-318-3. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

- ^ a b c d e f Morton, J. F. (1987). Fruits of Warm Climates. Florida Flair Books. ISBN 0-9610184-1-0.

- ^ Brown, Michael J. (1997). Durio — A Bibliographic Review (PDF). International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRI). pp. p. 2, also, see pp. 5–6 regarding whether Linnaeus or Murray is the correct authority for the binomial name. ISBN 92-9043-318-3. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Whitten, Tony (2001). The Ecology of Sumatra. Periplus. pp. p. 329. ISBN 962-593-074-4.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Yumoto, Takakazu (2000). "Bird-pollination of Three Durio Species (Bombacaceae) in a Tropical Rainforest in Sarawak, Malaysia". American Journal of Botany. 87 (8): p. 1181–1188.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ "Comprehensive List of Durian Clones Registered by the Agriculture Department (of Malaysia)". Durian OnLine. Retrieved 2006-03-05.

- ^ a b c Fuller, Thomas (2007-04-08). "Fans Sour on Sweeter Version of Asia's Smelliest Fruit". New York Times. Retrieved 2007-04-08.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ M.B. Osman, Z.A. Mohamed, S. Idris and R. Aman (1995). "Tropical fruit production and genetic resources in Southeast Asia: Identifying the priority fruit species". International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRI). ISBN 92-9043-249-7. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "Committee on Commodity Problems — VI. Overview of Minor Tropical Fruits". FAO. December 2001. Retrieved 2006-03-04.

- ^ Watson, B. J (1983). "Durian". Fact Sheet No. 6.: Rare Fruits Council of Australia.

- ^ Wallace, Alfred Russel (1856). "On the Bamboo and Durian of Borneo". Retrieved 2007-03-12.

- ^ Winokur, Jon (Ed.) (2003). The Traveling Curmudgeon: Irreverent Notes, Quotes, and Anecdotes on Dismal Destinations, Excess Baggage, the Full Upright Position, and Other Reasons Not to Go There. Sasquatch Books. pp. p. 102. ISBN 1-57061-389-3.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ a b c d e Davidson, Alan (1999). The Oxford Companion to Food. Oxford University Press. pp. p. 263. ISBN 0-19-211579-0.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ O'Gara, E., Guest, D. I. and Hassan, N. M. (2004). "8.2 Occurrence, Distribution and Utilisation of Durian Germplasm" (PDF). Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR). Retrieved 2007-03-13.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Marinelli, Janet (Ed.) (1998). Brooklyn Botanic Garden Gardener's Desk Reference. Henry Holt and Co. pp. p. 691. ISBN 0-8050-5095-7.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ a b McGee, Harold (2004). On Food and Cooking (Revised Edition). Scribner. pp. p. 379. ISBN 0-684-80001-2.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Montagne, Prosper (Ed.) (2001). Larousse Gastronomique. Clarkson Potter. pp. p. 439. ISBN 0609609718.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ a b "Durian & Mangosteens". Prositech.com. Retrieved 2006-07-01.

- ^ Davidson, Alan (1999). The Oxford Companion to Food. Oxford University Press. pp. p. 737. ISBN 0-19-211579-0.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ a b "Agroforestry Tree Database - Durio zibethinus". International Center for Research in Agroforestry. Retrieved 2007-03-12.

- ^ Banfield, E. J., (1911). My Tropic Isle. T. Fisher Unwin. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Traditional Cuisine". Sabah Tourism Promotion Corporation. Retrieved 2007-03-10.

- ^ "Durian Recipe Gallery". Durian Online. Retrieved 2006-03-03.

- ^ "Question No. 18085: Is it true that durian seeds are poisonous?". Singapore Science Centre. 2006. Retrieved 2006-03-20.

- ^ Crane, E. (Ed.) (1976). Honey: A Comprehensive Survey. Bee Research Association.

- ^ "USDA National Nutrient Database". U.S. Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 2007-03-23.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on 2024-03-27. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. Archived from the original on 2024-05-09. Retrieved 2024-06-21.

- ^ Wolfe, David (2002). Eating For Beauty. Maul Brothers Publishing. ISBN 0965353370.

- ^ Boutenko, Victoria (2001). 12 Steps to Raw Foods: How to End Your Addiction to Cooked Food. Raw Family. pp. p. 6. ISBN 0970481934.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Mars, Brigitte (2004). Rawsome!: Maximizing Health, Energy, and Culinary Delight With the Raw Foods Diet. Basic Health Publications. pp. p.103. ISBN 1591200601.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Cousens, Gabriel (2003). Rainbow Green Live-Food Cuisine. North Atlantic Books. pp. p. 34. ISBN 1556434650.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Klein, David (2005). "Vegan Healing Diet Guidelines". Self Healing Colitis & Crohn's. Living Nutrition Publications. ISBN 0971752613.

- ^ Burkill, I.H. and Haniff, M. (1930). "Malay village medicine, prescriptions collected". Gardens Bulletin Straits Settlements (6): p. 176-177.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Huang, Kee C. (1998). The Pharmacology of Chinese Herbs (Second Edition). CRC Press. pp. p. 2. ISBN 0849316650.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ McElroy, Anne and Townsend, Patricia K. (2003). Medical Anthropology in Ecological Perspective. Westview Press. pp. p. 253. ISBN 0813338212.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Vetterling, Herman (2003, first printed in 1923). Illuminate of Gorlitz or Jakob Bohme's Life and Philosophy, Part 3. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0-7661-4788-6.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) p. 1380. - ^ Echols, John M. (1989). An Indonesian-English Dictionary. Cornell University Press. pp. p. 292. ISBN 0801421276.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ The mangosteen, called as the "queen of fruits", is petite and mild in comparison. The mangosteen season coincides with that of the durian and is seen as a complement, which is probably how the mangosteen received the complementary title.

- ^ Template:Ja icon "ドラゴンボール登場人物名前由来". ドラゴンボールマニア (Dragon Ball Mania). Retrieved 2007-02-11.

- ^ "Tropical Cyclone Names". Japan Meteorological Agency. Retrieved 2007-03-10.

- ^ Lian, Hah Foong (2000-01-02). "Village abuzz over sighting of 'mawas'". Star Publications, Malaysia. Retrieved 2007-03-09.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Do 'orang pendek' really exist?". Jambiexplorer.com. Retrieved 2006-03-19.