Fibrinogen

| Fibrinogen alpha/beta chain family | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

crystal structure of native chicken fibrinogen with two different bound ligands | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Fib_alpha | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF08702 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR012290 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1m1j / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Fibrinogen alpha C domain | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Fibrinogen_aC | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF12160 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR021996 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symbol | Fibrinogen_C | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00147 | ||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0422 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR002181 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00445 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1fza / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Fibrinogen (coagulation factor I) is a glycoprotein complex, produced in the liver,[1] that circulates in the blood of all vertebrates.[2] During tissue and vascular injury, it is converted enzymatically by thrombin to fibrin and then to a fibrin-based blood clot. Fibrin clots function primarily to occlude blood vessels to stop bleeding. Fibrin also binds and reduces the activity of thrombin. This activity, sometimes referred to as antithrombin I, limits clotting.[1] Fibrin also mediates blood platelet and endothelial cell spreading, tissue fibroblast proliferation, capillary tube formation, and angiogenesis and thereby promotes revascularization and wound healing.[3]

Reduced and/or dysfunctional fibrinogens occur in various congenital and acquired human fibrinogen-related disorders. These disorders represent a group of rare conditions in which individuals may present with severe episodes of pathological bleeding and thrombosis; these conditions are treated by supplementing blood fibrinogen levels and inhibiting blood clotting, respectively.[4][5] These disorders may also be the cause of certain liver and kidney diseases.[1]

Fibrinogen is a "positive" acute-phase protein, i.e. its blood levels rise in response to systemic inflammation, tissue injury, and certain other events. It is also elevated in various cancers. Elevated levels of fibrinogen in inflammation as well as cancer and other conditions have been suggested to be the cause of thrombosis and vascular injury that accompanies these conditions.[6][7]

Genes

[edit]Fibrinogen is made and secreted into the blood primarily by liver hepatocyte cells. Endothelium cells are also reported to make small amounts of fibrinogen, but this fibrinogen has not been fully characterized; blood platelets and their precursors, bone marrow megakaryocytes, while once thought to make fibrinogen, are now known to take up and store but not make the glycoprotein.[4][7] The final secreted, hepatocyte-derived glycoprotein is composed of two trimers, with each trimer composed of three different polypeptide chains, the fibrinogen alpha chain (also termed the Aα or α chain) encoded by the FGA gene, the fibrinogen beta chain (also termed the Bβ or β chain) encoded by the FGB gene, and the fibrinogen gamma chain (also termed the γ chain) encoded by the FGG gene. All three genes are located on the long or "q" arm of human chromosome 4 (at positions 4q31.3, 4q31.3, and 4q32.1, respectively).[1]

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Alternate splicing of the FGA gene produces a minor expanded isoform of Aα termed AαE which replaces Aα in 1–3% of circulating fibrinogen; alternate splicing of FGG produces a minor isoform of γ termed γ' which replaces γ in 8–10% of circulating fibrinogen; FGB is not alternatively spliced. Hence, the final fibrinogen product is composed principally of Aα, Bβ, and γ chains with a small percentage of it containing AαE and/or γ' chains in place of Aα and/or γ chains, respectively. The three genes are transcribed and translated in co-ordination by a mechanism(s) which remains incompletely understood.[8][9][10][11][12] The coordinated transcription of these three fibrinogen genes is rapidly and greatly increased by systemic conditions such as inflammation and tissue injury. Cytokines produced during these systemic conditions, such as interleukin 6 and interleukin 1β, appear responsible for up-regulating this transcription.[11]

Structure

[edit]

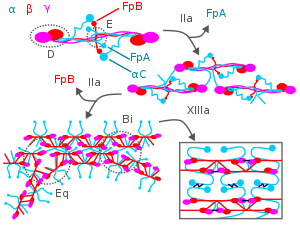

The Aα, Bβ, and γ chains are transcribed and translated coordinately on the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), with their peptide chains being passed into the ER while their signal peptide portions are removed. Inside the ER, the three chains are assembled initially into Aαγ and Bβγ dimers, then to AαBβγ trimers, and finally to (AαBβγ)2 heximers, i.e. two AαBβγ trimers joined by numerous disulfide bonds. The heximer is transferred to the Golgi where it is glycosylated, hydroxylated, sulfated, and phosphorylated to form the mature fibrinogen glycoprotein that is secreted into the blood.[10][12] Mature fibrinogen is arranged as a long flexible protein array of three nodules held together by a very thin thread which is estimated to have a diameter between 8 and 15 angstroms (Å). The two end nodules (termed D regions or domains) are alike in consisting of Bβ and γ chains, while the center slightly smaller nodule (termed the E region or domain) consists of two intertwined Aα alpha chains. Measurements of shadow lengths indicate that nodule diameters are in the range 50 to 70 Å. The length of the dried molecule is 475 ± 25 Å.[14]

The fibrinogen molecule circulates as a soluble plasma glycoprotein with a typical molecular weight of ~340 – ~420 kDa (kilodaltons)[15] (depending on its content of Aα verses AαE, γ versus γ' chains, and carbohydrate [~4 – ~10%w/w]). It has a rod-like shape with dimensions of 9 × 47.5 × 6 nm and has a negative net charge at physiological pH (its isoelectric point ~5.5 – ~6.5, e.g. pH 5.8[16][17]). The normal concentration of fibrinogen in blood plasma is 150–400 mg/dl, with levels appreciably below or above this range associated with pathological bleeding and/or thrombosis. Fibrinogen has a circulating half-life of ~4 days.[12]

Blood clot formation

[edit]

During blood clotting, thrombin attacks the N-terminus of the Aα and Bβ chains in fibrinogen to form individual fibrin strands plus two small polypeptides, fibrinopeptides A and B derived from these respective chains. The individual fibrin strands then polymerize and are crosslinked with other fibrin strands by blood factor XIIIa to form an extensive interconnected fibrin network that is the basis for the formation of a mature fibrin clot.[3][7][18] In addition to forming fibrin, fibrinogen also promotes blood clotting by forming bridges between, and activating, blood platelets through binding to their GpIIb/IIIa surface membrane fibrinogen receptor.[18]

Fibrin participates in limiting blood clot formation and degrading formed blood clots by at least two important mechanisms. First, it possesses three low affinity binding sites (two in fibrin's E domain; one in its D domain) for thrombin; this binding sequesters thrombin from attacking fibrinogen.[18] Second, fibrin's Aα chain accelerates by at least 100-fold the amount of plasmin activated by tissue plasminogen activator; plasmin breaks-down blood clots.[5][18][3][7] Plasmin's attack on fibrin releases D-dimers (also termed DD dimers). The detection of these dimers in blood is used as a clinical test for fibrinolysis.[5]

Fibrinogen disorders

[edit]Several disorders in the quantity and/or quality of fibrinogen cause pathological bleeding, pathological blood clotting, and/or the deposition of fibrinogen in the liver, kidneys, and other tissues.

Congenital afibrinogenemia

[edit]Congenital afibrinogenemia is a rare and generally autosomal recessive inherited disorder in which blood does not clot due to a lack of fibrinogen (plasma fibrinogen levels typically) but sometimes detected at extremely low levels, e.g. <10 mg/dl. This severe disorder is usually caused by mutations in both the maternal and paternal copies of either the FGA, FGB, or FBG gene. The mutations have virtually complete genetic penetrance with essentially all homozygous bearers experiencing frequent and sometimes life-threatening episodes of bleeding and/or thrombosis. Pathological bleeding occurs early in life, for example often being seen at birth with excessive hemorrhage from the navel.[4]

Congenital hypofibrinogenemia

[edit]Congenital hypofibrinogenemia is a rare inherited disorder in which blood may not clot normally due to reduced levels of fibrinogen (plasma fibrinogen typically <150 but >50 mg/dl). The disorder reflects a disruptive mutation in only one of the two parental FGA, FGB, or FBG genes and has a low degree of genetic penetrance, i.e. only some family members with the defective gene ever exhibit symptoms. Symptoms of the disorder, which more often occurs in individuals with lower plasma fibrinogen levels, include episodic bleeding and thrombosis that typically begin in late childhood or adulthood.[4]

Fibrinogen storage disease

[edit]Fibringogen storage disease is an extremely rare disorder. It is a form of congenital hypofibrinogenemia in which certain specific hereditary mutations in one copy of the FGG gene causes its fibrinogen product to accumulate in, and damage, liver cells. The disorder has not reported with FGA or FGB mutations. Symptoms of these FGG mutations have a low level of penetrance. The plasma fibrinogen levels (generally <150 but >50 mg/dl) detected in this disorder reflect the fibrinogen made by the normal gene. Fibrinogen storage disease may lead to abnormal bleeding and thrombosis but is distinguished by also sometimes leading to liver cirrhosis.[19]

Congenital dysfibrinogenemia

[edit]Congenital dysfibrinogenemia is a rare autosomal dominant inherited disorder in which plasma fibrinogen is composed of a dysfunctional fibrinogen made by a mutated FGA, FGB, or FBG gene inherited from one parent plus a normal fibrinogen made by a normal gene inherited from the other parent. As a reflection of this duality, plasma fibrinogen levels measured by immunological methods are normal (>150 mg/dl) but are c. 50% lower when measured by clot formation methods. The disorder exhibits reduced penetrance, with only some individuals with the abnormal gene showing symptoms of abnormal bleeding and thrombosis.[20]

Hereditary fibrinogen Aα-Chain amyloidosis

[edit]Hereditary fibrinogen Aα-Chain amyloidosis is an autosomal dominant extremely rare inherited disorder caused by a mutation in one of the two copies of the FGA gene. It is a form of congenital dysfibrinogenemia in which certain mutations lead to the production of an abnormal fibrinogen that circulates in the blood while gradually accumulating in the kidney. This accumulation leads over time to one form of familial renal amyloidosis. Plasma fibrinogen levels are similar to that seen in other forms of congenital dysfibrinogenemia. Fibrinogen Aα-Chain amyloidosis has not associated with abnormal bleeding or thrombosis.[21]

Acquired dysfibrinogenemia

[edit]Acquired dysfibrinogenemia is a rare disorder in which circulating fibrinogen is composed at least in part of a dysfunctional fibrinogen due to various acquired diseases. One well-studied cause of the disorder is severe liver disease including hepatoma, chronic active hepatitis, cirrhosis, and jaundice due to biliary tract obstruction. The diseased liver synthesizes a fibrinogen which has a normally functional amino acid sequence but is incorrectly glycosylated (i.e. has a wrong amount of sugar residues) added to it during its passage through the Golgi. The incorrectly glycosalated fibrinogen is dysfunctional and may cause pathological episodes of bleeding and/or blood clotting. Other, less well understood, causes are plasma cell dyscrasias and autoimmune disorders in which a circulating abnormal immunoglobulin or other protein interferes with fibrinogen function, and rare cases of cancer and medication (isotretinoin, glucocorticoids, and antileukemic drugs) toxicities.[18]

Congenital hypodysfibrinogenemia

[edit]Congenital hypodysfibrinogenemia is a rare inherited disorder in which low levels (i.e. <150 mg/dl) of immunologically detected plasma fibrinogen are composed at least in part of a dysfunctional fibrinogen. The disorder reflects mutations typically in both inherited fibrinogen genes, one of which produces a dysfunctional fibrinogen, while the other produces low amounts of fibrinogen. The disorder, while having reduced penetrance, is usually more severe than congenital dysfibrinogenemia, but like the latter disorder, causes pathological episodes of bleeding and/or blood clotting.[22]

Cryofibrinogenemia

[edit]Cryofibrinogenemia is an acquired disorder in which fibrinogen precipitates at cold temperatures and may lead to the intravascular precipitation of fibrinogen, fibrin, and other circulating proteins, thereby causing the infarction of various tissues and bodily extremities. Cryoglobulonemia may occur without evidence of an underlying associated disorders, i.e. primary cryoglobulinemia (also termed essential cryoglobulinemia) or, far more commonly, with evidence of an underlying disease, i.e. secondary cryoglobulonemia. Secondary cryofibrinoenemia can develop in individuals with infection (c. 12% of cases), malignant or premalignant disorders (21%), vasculitis (25%), and autoimmune diseases (42%). In these cases, cryofibinogenema may or may not cause tissue injury and/or other symptoms and the actual cause-effect relationship between these diseases and the development of cryofibrinogenmia is unclear. Cryofibrinogenemia can also occur in association with the intake of certain drugs.[23][24][25][26]

Acquired hypofibrinogenemia

[edit]Acquired hypofibrinogenemia is a deficiency in circulating fibrinogen due to excessive consumption that may occur as a result of trauma, certain phases of disseminated intravascular coagulation, and sepsis. It may also occur as a result of hemodilution as a result of blood losses and/or transfusions with packed red blood cells or other fibrinogen-poor whole blood replacements.[27]

Laboratory tests

[edit]Clinical analyses of the fibrinogen disorders typically measure blood clotting using the following successive steps:[28] Higher levels are, amongst others, associated with cardiovascular disease (>3.43 g/L).[clarification needed] It may be elevated in any form of inflammation, as it is an acute-phase protein; for example, it is especially apparent in human gingival tissue during the initial phase of periodontal disease.[29][30]

- Blood clotting is measured using standard tests, e.g. prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, thrombin time, and/or reptilase time. Low fibrinogen levels and dysfunctional fibrinogens usually prolong these times, whereas the lack of fibrinogen (i.e. afibrinogenemia) renders these times infinitely prolonged.

- Fibrinogen levels are measured in the plasma isolated from venous blood by immunoassays,[citation needed] or through clotting assays such as the Clauss fibrinogen assay or prothrombin based methods.[31] Normal levels being about 1.5-3 g/L, depending on the method used. These levels are normal in dysfibrinogenemia (i.e. 1.5-3 g/L), decreased in hypofibrinogenemia and hypodysfibrinogenemia (i.e. <1.5 g/L), and absent (i.e. <0.02 g/L) in afibrinogenemia.

- Functional levels of fibrinogen are measured on plasma induced to clot. The levels of clotted fibrinogen in this test should be decreased in hypofibrinogenemia, hypodysfibrinogenemia, and dysfibrinogenemia and undetectable in afibrinogenemia.

- Functional fibrinogen/antigenic fibrinogen levels are <0.7 g/L in hypofibrinogenemia, hypodysfibrinogenemia, and dysfibrogenemia, and not applicable in afibrinogenemia.

- Fibrinogen analysis can also be tested on whole-blood samples by thromboelastometry. This analysis investigates the interaction of coagulation factors, their inhibitors, anticoagulant drugs, and blood cells (specifically, platelets), during clotting and subsequent fibrinolysis as it occurs in whole blood. The test provides information on hemostatic efficacy and maximum clot firmness to give additional information on fibrin-platelet interactions and the rate of fibrinolysis (see Thromboelastometry).

- Scanning electron microscopy and confocal laser scanning microscopy of in vitro-formed clots can give information on fibrin clot density and architecture.

- The fibrinogen uptake test or fibrinogen scan was formerly used to detect deep vein thrombosis. In this method, radioactively labeled fibrinogen, typically with radioiodine, is given to individuals, incorporated into a thrombus, and detected by scintigraphy.

Hyperfibrinogenemia

[edit]Levels of functionally normal fibrinogen increase in pregnancy to an average of 4.5 gram/liter (g/L) compared to an average of 3 g/L in non-pregnant people. They may also increase in various forms of cancer, particularly gastric, lung, prostate, and ovarian cancers. In these cases, the hyperfibrinogenemia may contribute to the development of pathological thrombosis. A particular pattern of migratory superficial vein thrombosis, termed trousseau's syndrome, occurs in, and may precede all other signs and symptoms of, these cancers.[7][32] Hyperfibrinogenemia has also been linked as a cause of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn[33] and post-operative thrombosis.[34] High fibrinogen levels had been proposed as a predictor of hemorrhagic complications during catheter-directed thrombolysis for acute or subacute peripheral native artery and arterial bypass occlusions.[35] However, a systematic review of the available literature until January 2016 found that the predictive value of plasma fibrinogen level for predicting hemorrhagic complications after catheter-directed thrombolysis is unproven.[36]

History

[edit]Paul Morawitz in 1905 described fibrinogen.[37]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d de Moerloose P, Casini A, Neerman-Arbez M (September 2013). "Congenital fibrinogen disorders: an update". Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis. 39 (6): 585–595. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1349222. PMID 23852822.

- ^ Jiang Y, Doolittle RF (June 2003). "The evolution of vertebrate blood coagulation as viewed from a comparison of puffer fish and sea squirt genomes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 100 (13): 7527–7532. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.7527J. doi:10.1073/pnas.0932632100. PMC 164620. PMID 12808152.

- ^ a b c Mosesson MW (August 2005). "Fibrinogen and fibrin structure and functions". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 3 (8): 1894–1904. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01365.x. PMID 16102057. S2CID 22077267.

- ^ a b c d Casini A, de Moerloose P, Neerman-Arbez M (June 2016). "Clinical Features and Management of Congenital Fibrinogen Deficiencies". Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis. 42 (4): 366–374. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1571339. PMID 27019462. S2CID 12038872.

- ^ a b c Undas A (September 2011). "Acquired dysfibrinogenemia in atherosclerotic vascular disease". Polskie Archiwum Medycyny Wewnetrznej. 121 (9): 310–319. PMID 21952526.

- ^ Davalos D, Akassoglou K (January 2012). "Fibrinogen as a key regulator of inflammation in disease". Seminars in Immunopathology. 34 (1): 43–62. doi:10.1007/s00281-011-0290-8. PMID 22037947. S2CID 14997530.

- ^ a b c d e Repetto O, De Re V (September 2017). "Coagulation and fibrinolysis in gastric cancer". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1404 (1): 27–48. Bibcode:2017NYASA1404...27R. doi:10.1111/nyas.13454. PMID 28833193. S2CID 10878584.

- ^ Neerman-Arbez M, de Moerloose P, Casini A (June 2016). "Laboratory and Genetic Investigation of Mutations Accounting for Congenital Fibrinogen Disorders". Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis. 42 (4): 356–365. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1571340. PMID 27019463. S2CID 12693693.

- ^ Duval C, Ariëns RA (July 2017). "Fibrinogen splice variation and cross-linking: Effects on fibrin structure/function and role of fibrinogen γ' as thrombomobulin II" (PDF). Matrix Biology. 60–61: 8–15. doi:10.1016/j.matbio.2016.09.010. PMID 27784620.

- ^ a b Vu D, Neerman-Arbez M (July 2007). "Molecular mechanisms accounting for fibrinogen deficiency: from large deletions to intracellular retention of misfolded proteins". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 5 (Suppl 1): 125–131. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02465.x. PMID 17635718. S2CID 27354717.

- ^ a b Fish RJ, Neerman-Arbez M (September 2012). "Fibrinogen gene regulation". Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 108 (3): 419–426. doi:10.1160/TH12-04-0273. PMID 22836683. S2CID 9763486.

- ^ a b c Asselta R, Duga S, Tenchini ML (October 2006). "The molecular basis of quantitative fibrinogen disorders". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 4 (10): 2115–2129. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02094.x. PMID 16999847. S2CID 24223328.

- ^ a b c d Topaz O, et al. (2018). Cardiovascular thrombus. Academic Press. pp. 31–43. ISBN 9780128126165.

- ^ Hall CE, Slayter HS (January 1959). "The fibrinogen molecule: its size, shape, and mode of polymerization". The Journal of Biophysical and Biochemical Cytology. 5 (1): 11–16. doi:10.1083/jcb.5.1.11. PMC 2224630. PMID 13630928.

- ^ Fantl P, Ward HA (September 1965). "Molecular weight of human fibrinogen derived from phosphorus determinations". The Biochemical Journal. 96 (3): 886–889. doi:10.1042/bj0960886. PMC 1207232. PMID 5862426.

- ^ Marucco A, Fenoglio I, Turci F, Fubini B (2013). "Interaction of fibrinogen and albumin with titanium dioxide nanoparticles of different crystalline phases". Journal of Physics. Conference Series. 429 (1): 012014. Bibcode:2013JPhCS.429a2014M. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/429/1/012014. hdl:2318/130247. S2CID 1575697.

- ^ Cieśla M, Adamczyk Z, Barbasz J, Wasilewska M (June 2013). "Mechanisms of fibrinogen adsorption at solid substrates at lower pH". Langmuir. 29 (23): 7005–7016. doi:10.1021/la4012789. PMID 23621148.

- ^ a b c d e Besser MW, MacDonald SG (2016). "Acquired hypofibrinogenemia: current perspectives". Journal of Blood Medicine. 7: 217–225. doi:10.2147/JBM.S90693. PMC 5045218. PMID 27713652.

- ^ Casini A, Sokollik C, Lukowski SW, Lurz E, Rieubland C, de Moerloose P, Neerman-Arbez M (November 2015). "Hypofibrinogenemia and liver disease: a new case of Aguadilla fibrinogen and review of the literature". Haemophilia. 21 (6): 820–827. doi:10.1111/hae.12719. PMID 25990487. S2CID 44911581.

- ^ Casini A, Neerman-Arbez M, Ariëns RA, de Moerloose P (June 2015). "Dysfibrinogenemia: from molecular anomalies to clinical manifestations and management". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 13 (6): 909–919. doi:10.1111/jth.12916. PMID 25816717. S2CID 10955092.

- ^ Gillmore JD, Lachmann HJ, Rowczenio D, Gilbertson JA, Zeng CH, Liu ZH, et al. (February 2009). "Diagnosis, pathogenesis, treatment, and prognosis of hereditary fibrinogen A alpha-chain amyloidosis". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 20 (2): 444–451. doi:10.1681/ASN.2008060614. PMC 2637055. PMID 19073821.

- ^ Casini A, Brungs T, Lavenu-Bombled C, Vilar R, Neerman-Arbez M, de Moerloose P (May 2017). "Genetics, diagnosis and clinical features of congenital hypodysfibrinogenemia: a systematic literature review and report of a novel mutation". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 15 (5): 876–888. doi:10.1111/jth.13655. PMID 28211264.

- ^ Grada A, Falanga V (February 2017). "Cryofibrinogenemia-Induced Cutaneous Ulcers: A Review and Diagnostic Criteria". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. 18 (1): 97–104. doi:10.1007/s40257-016-0228-y. PMID 27734332. S2CID 39645385.

- ^ Chen Y, Sreenivasan GM, Shojania K, Yoshida EM (June 2015). "Cryofibrinogenemia After a Liver Transplant: First Reported Case Posttransplant and a Case-Based Review of the Nontransplant Literature". Experimental and Clinical Transplantation. 13 (3): 290–294. doi:10.6002/ect.2014.0013. PMID 24679054.

- ^ Caimi G, Canino B, Lo Presti R, Urso C, Hopps E (2017). "Clinical conditions responsible for hyperviscosity and skin ulcers complications". Clinical Hemorheology and Microcirculation. 67 (1): 25–34. doi:10.3233/CH-160218. hdl:10447/238851. PMID 28550239.

- ^ Michaud M, Pourrat J (April 2013). "Cryofibrinogenemia". Journal of Clinical Rheumatology. 19 (3): 142–148. doi:10.1097/RHU.0b013e318289e06e. PMID 23519183.

- ^ Fries D, Innerhofer P, Schobersberger W (April 2009). "Time for changing coagulation management in trauma-related massive bleeding". Current Opinion in Anesthesiology. 22 (2): 267–274. doi:10.1097/ACO.0b013e32832678d9. PMID 19390253. S2CID 10615690.

- ^ Lang T, Johanning K, Metzler H, Piepenbrock S, Solomon C, Rahe-Meyer N, Tanaka KA (March 2009). "The effects of fibrinogen levels on thromboelastometric variables in the presence of thrombocytopenia". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 108 (3): 751–758. doi:10.1213/ane.0b013e3181966675. PMID 19224779. S2CID 11733489.

- ^ Page RC, Schroeder HE (March 1976). "Pathogenesis of inflammatory periodontal disease. A summary of current work". Laboratory Investigation; A Journal of Technical Methods and Pathology. 34 (3): 235–249. PMID 765622.

- ^ Nagler M, Kremer Hovinga JA, Alberio L, Peter-Salonen K, von Tengg-Kobligk H, Lottaz D, et al. (September 2016). "Thromboembolism in patients with congenital afibrinogenaemia. Long-term observational data and systematic review" (PDF). Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 116 (4): 722–732. doi:10.1160/TH16-02-0082. PMID 27384135. S2CID 4959738.

- ^ Lawrie AS, McDonald SJ, Purdy G, Mackie IJ, Machin SJ (June 1998). "Prothrombin time derived fibrinogen determination on Sysmex CA-6000". Journal of Clinical Pathology. 51 (6): 462–466. doi:10.1136/jcp.51.6.462. PMC 500750. PMID 9771446.

- ^ Salvi V (2003). Medical and Surgical Diagnostic Disorders in Pregnancy. Jaypee Brothers Publishers. p. 5. ISBN 978-81-8061-090-5.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Graves ED, Redmond CR, Arensman RM (March 1988). "Persistent pulmonary hypertension in the neonate". Chest. 93 (3): 638–641. doi:10.1378/chest.93.3.638. PMID 3277808.

- ^ Müller R, Musikić P (August 1987). "Hemorheology in surgery--a review". Angiology. 38 (8): 581–592. doi:10.1177/000331978703800802. PMID 3307545. S2CID 23209838.

- ^ "Results of a prospective randomized trial evaluating surgery versus thrombolysis for ischemia of the lower extremity. The STILE trial". Annals of Surgery. 220 (3): 251–266, discussion 266–268. September 1994. doi:10.1097/00000658-199409000-00003. PMC 1234376. PMID 8092895.

- ^ Poorthuis MH, Brand EC, Hazenberg CE, Schutgens RE, Westerink J, Moll FL, de Borst GJ (May 2017). "Plasma fibrinogen level as a potential predictor of hemorrhagic complications after catheter-directed thrombolysis for peripheral arterial occlusions". Journal of Vascular Surgery. 65 (5): 1519–1527.e26. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2016.11.025. PMID 28274749.

- ^ Izaguirre Avila R (2005). "[The centennial of blood coagulation doctrine]". Archivos de Cardiologia de Mexico (in Spanish). 75 (Suppl 3): S3–118–29. PMID 16366177.

External links

[edit]- Jennifer McDowall/Interpro: Protein of the Month: Fibrinogen.

- Peter D'Eustachio/reactome: fibrinogen → fibrin monomer + 2 fibrinopeptide A + 2 fibrinopeptide B

- Khan Academy Medicine (on YouTube): Clotting 1 - How do we make blood clots?

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: P02671 (Fibrinogen alpha chain) at the PDBe-KB.

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: P02675 (Fibrinogen beta chain) at the PDBe-KB.

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: P02679 (Fibrinogen gamma chain) at the PDBe-KB.