G

| G | |

|---|---|

| G g | |

| (See below, Typographic) | |

| |

| Usage | |

| Writing system | Latin script |

| Type | Alphabetic |

| Language of origin | Latin language |

| Sound values | [g] [d͡ʒ] [ʒ] [ŋ] [j] [ɣ~ʝ] [x~χ] [d͡z] [ɟ] [k] [ɠ] [ɢ] /dʒiː/ |

| In Unicode | U+0047, U+0067, U+0261 |

| Alphabetical position | 7 |

| History | |

| Development | |

| Time period | ~-300 to present |

| Descendants | • ₲ • Ȝ • Ᵹ • |

| Sisters | C Г ג ج ܓ ࠂ ℷ 𐡂 Գ գ |

| Transliterations | C |

| Variations | (See below, Typographic) |

| Other | |

| Associated graphs | gh, g(x) |

| Writing direction | Left-to-Right |

| ISO basic Latin alphabet |

|---|

| AaBbCcDdEeFfGgHhIiJjKkLlMmNnOoPpQqRrSsTtUuVvWwXxYyZz |

G (named gee /dʒiː/)[1] is the 7th letter in the ISO basic Latin alphabet.

History

The letter 'G' was introduced in the Old Latin period as a variant of 'C' to distinguish voiced /ɡ/ from voiceless /k/. The recorded originator of 'G' is freedman Spurius Carvilius Ruga, the first Roman to open a fee-paying school, who taught around 230 BCE. At this time, 'K' had fallen out of favor, and 'C', which had formerly represented both /ɡ/ and /k/ before open vowels, had come to express /k/ in all environments.

Ruga's positioning of 'G' shows that alphabetic order related to the letters' values as Greek numerals was a concern even in the 3rd century BC. According to some records, the original seventh letter, 'Z', had been purged from the Latin alphabet somewhat earlier in the 3rd century BC by the Roman censor Appius Claudius, who found it distasteful and foreign.[2] Sampson (1985) suggests that: "Evidently the order of the alphabet was felt to be such a concrete thing that a new letter could be added in the middle only if a 'space' was created by the dropping of an old letter."[3]

George Hempl (1899) proposes that there never was such a "space" in the alphabet and that in fact 'G' was a direct descendant of zeta. Zeta took shapes like ⊏ in some of the Old Italic scripts; the development of the monumental form 'G' from this shape would be exactly parallel to the development of 'C' from gamma. He suggests that the pronunciation /k/ > /ɡ/ was due to contamination from the also similar-looking 'K'.[4]

Eventually, both velar consonants /k/ and /ɡ/ developed palatalized allophones before front vowels; consequently in today's Romance languages, ⟨c⟩ and ⟨g⟩ have different sound values depending on context (known as hard and soft C and hard and soft G). Because of French influence, English orthography shares this feature.

Typographic variants

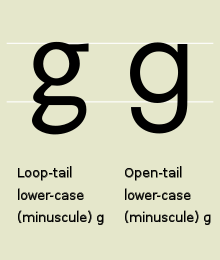

The modern lowercase 'g' has two typographic variants: the single-storey (sometimes opentail) '![]() ' and the double-storey (sometimes looptail) '

' and the double-storey (sometimes looptail) '![]() '. The single-storey form derives from the majuscule (uppercase) form by raising the serif that distinguishes it from 'c' to the top of the loop, thus closing the loop, and extending the vertical stroke downward and to the left. The double-storey form (g) had developed similarly, except that some ornate forms then extended the tail back to the right, and to the left again, forming a closed bowl or loop. The initial extension to the left was absorbed into the upper closed bowl. The double-storey version became popular when printing switched to "Roman type" because the tail was effectively shorter, making it possible to put more lines on a page. In the double-storey version, a small top stroke in the upper-right, often terminating in an orb shape, is called an "ear".

'. The single-storey form derives from the majuscule (uppercase) form by raising the serif that distinguishes it from 'c' to the top of the loop, thus closing the loop, and extending the vertical stroke downward and to the left. The double-storey form (g) had developed similarly, except that some ornate forms then extended the tail back to the right, and to the left again, forming a closed bowl or loop. The initial extension to the left was absorbed into the upper closed bowl. The double-storey version became popular when printing switched to "Roman type" because the tail was effectively shorter, making it possible to put more lines on a page. In the double-storey version, a small top stroke in the upper-right, often terminating in an orb shape, is called an "ear".

Generally, the two forms are complementary, but occasionally the difference has been exploited to provide contrast. In the International Phonetic Alphabet, opentail ⟨ɡ⟩ has always represented a voiced velar plosive, while ⟨![]() ⟩ was distinguished from ⟨ɡ⟩ and represented a voiced velar fricative from 1895 to 1900.[5][6] In 1948, the Council of the International Phonetic Association recognized ⟨ɡ⟩ and ⟨

⟩ was distinguished from ⟨ɡ⟩ and represented a voiced velar fricative from 1895 to 1900.[5][6] In 1948, the Council of the International Phonetic Association recognized ⟨ɡ⟩ and ⟨![]() ⟩ as typographic equivalents,[7] and this decision was reaffirmed in 1993.[8] While the 1949 Principles of the International Phonetic Association recommended the use of ⟨

⟩ as typographic equivalents,[7] and this decision was reaffirmed in 1993.[8] While the 1949 Principles of the International Phonetic Association recommended the use of ⟨![]() ⟩ for a velar plosive and ⟨ɡ⟩ for an advanced one for languages where it is preferable to distinguish the two, such as Russian,[9] this practice never caught on.[10] The 1999 Handbook of the International Phonetic Association, the successor to the Principles, abandoned the recommendation and acknowledged both shapes as acceptable variants.[11]

⟩ for a velar plosive and ⟨ɡ⟩ for an advanced one for languages where it is preferable to distinguish the two, such as Russian,[9] this practice never caught on.[10] The 1999 Handbook of the International Phonetic Association, the successor to the Principles, abandoned the recommendation and acknowledged both shapes as acceptable variants.[11]

Wong et al. (2018) found that native English speakers have little conscious awareness of the looptail 'g' (![]() ).[12][13] They write: "Despite being questioned repeatedly, and despite being informed directly that G has two lowercase print forms, nearly half of the participants failed to reveal any knowledge of the looptail 'g', and only 1 of the 38 participants was able to write looptail 'g' correctly."

).[12][13] They write: "Despite being questioned repeatedly, and despite being informed directly that G has two lowercase print forms, nearly half of the participants failed to reveal any knowledge of the looptail 'g', and only 1 of the 38 participants was able to write looptail 'g' correctly."

Use in writing systems

English

In English, the letter appears either alone or in some digraphs. Alone, it represents

- a voiced velar plosive (/ɡ/ or "hard" ⟨g⟩), as in goose, gargoyle and game;

- a voiced palato-alveolar affricate (/d͡ʒ/ or "soft" ⟨g⟩), generally before ⟨i⟩ or ⟨e⟩, as in giant, ginger and geology; or

- a voiced palato-alveolar sibilant (/ʒ/) in some words of French origin, such as rouge, beige and genre.

In words of Romance origin, ⟨g⟩ is mainly soft before ⟨e⟩ (including the digraphs ⟨ae⟩ and ⟨oe⟩), ⟨i⟩, or ⟨y⟩, and hard otherwise. Soft ⟨g⟩ is also used in many words that came into English through medieval or modern Romance languages from languages without soft ⟨g⟩ (like Ancient Latin and Greek) (e.g. fragile or logic). There are many English words of non-Romance origin where ⟨g⟩ is hard though followed by ⟨e⟩ or ⟨i⟩ (e.g. get, gift), and a few in which ⟨g⟩ is soft though followed by ⟨a⟩ such as gaol or margarine.

The double consonant ⟨gg⟩ has the value /ɡ/ (hard ⟨g⟩) as in nugget, with very few exceptions: /ɡd͡ʒ/ in suggest and /d͡ʒ/ in exaggerate and veggies.

The digraph ⟨dg⟩ has the value /d͡ʒ/ (soft ⟨g⟩), as in badger. Non-digraph ⟨dg⟩ can also occur, in compounds like floodgate and headgear.

The digraph ⟨ng⟩ may represent

- a velar nasal (/ŋ/) as in length, singer

- the latter followed by hard ⟨g⟩ (/ŋɡ/) as in jungle, finger, longest

Non-digraph ⟨ng⟩ also occurs, with possible values

- /nɡ/ as in engulf, ungainly

- /nd͡ʒ/ as in sponge, angel

- /nʒ/ as in melange

The digraph ⟨gh⟩ (in many cases a replacement for the obsolete letter yogh, which took various values including /ɡ/, /ɣ/, /x/ and /j/) may represent

- /ɡ/ as in ghost, aghast, burgher, spaghetti

- /f/ as in cough, laugh, roughage

- Ø (no sound) as in through, neighbor, night

- /p/ in hiccough

- /x/ in ugh

Non-digraph ⟨gh⟩ also occurs, in compounds like foghorn, pigheaded

The digraph ⟨gn⟩ may represent

- /n/ as in gnostic, deign, foreigner, signage

- /nj/ in loanwords like champignon, lasagna

Non-digraph ⟨gn⟩ also occurs, as in signature, agnostic

The trigraph ⟨ngh⟩ has the value /ŋ/ as in gingham or dinghy. Non-trigraph ⟨ngh⟩ also occurs, in compounds like stronghold and dunghill.

Other languages

Most Romance languages and some Nordic languages also have two main pronunciations for ⟨g⟩, hard and soft. While the soft value of ⟨g⟩ varies in different Romance languages (/ʒ/ in French and Portuguese, [(d)ʒ] in Catalan, /d͡ʒ/ in Italian and Romanian, and /x/ in most dialects of Spanish), in all except Romanian and Italian, soft ⟨g⟩ has the same pronunciation as the ⟨j⟩.

In Italian and Romanian, ⟨gh⟩ is used to represent /ɡ/ before front vowels where ⟨g⟩ would otherwise represent a soft value. In Italian and French, ⟨gn⟩ is used to represent the palatal nasal /ɲ/, a sound somewhat similar to the ⟨ny⟩ in English canyon. In Italian, the trigraph ⟨gli⟩, when appearing before a vowel or as the article and pronoun gli, represents the palatal lateral approximant /ʎ/.

Other languages typically use ⟨g⟩ to represent /ɡ/ regardless of position.

Amongst European languages Czech, Dutch, Finnish and Slovak are an exception as they do not have /ɡ/ in their native words. In Dutch ⟨g⟩ represents a voiced velar fricative /ɣ/ instead, a sound that does not occur in modern English, but there is a dialectal variation: many Netherlandic dialects use a voiceless fricative ([x] or [χ]) instead, and in southern dialects it may be palatal [ʝ]. Nevertheless, word-finally it is always voiceless in all dialects, including the standard Dutch of Belgium and the Netherlands. On the other hand, some dialects (like Amelands), may have a phonemic /ɡ/.

Faroese uses ⟨g⟩ to represent /dʒ/, in addition to /ɡ/, and also uses it to indicate a glide.

In Maori (Te Reo Māori), ⟨g⟩ is used in the digraph ⟨ng⟩ which represents the velar nasal /ŋ/ and is pronounced like the ⟨ng⟩ in singer.

In older Czech and Slovak orthographies, ⟨g⟩ was used to represent /j/, while /ɡ/ was written as ⟨ǧ⟩ (⟨g⟩ with caron).

Related characters

Ancestors, descendants and siblings

- 𐤂 : Semitic letter Gimel, from which the following symbols originally derive

- C c : Latin letter C, from which G derives

- Γ γ : Greek letter Gamma, from which C derives in turn

- ɡ: Latin letter script small G

- ᶢ : Modifier letter small script g is used for phonetic transcription[14]

- ᵷ : Turned g

- Г г : Cyrillic letter Ge

- Ȝ ȝ : Latin letter Yogh

- Ɣ ɣ : Latin letter Gamma

- Ᵹ ᵹ : Insular g

- Ꝿ ꝿ : Turned insular g

- ɢ : Latin letter small capital G, used in the International Phonetic Alphabet to represent a voiced uvular stop

- ʛ : Latin letter small capital G with hook, used in the International Phonetic Alphabet to represent a voiced uvular implosive

- ᴳ ᵍ : Modifier letters are used in the Uralic Phonetic Alphabet[15]

- ꬶ : Used for the Teuthonista phonetic transcription system[16]

- G with diacritics: Ǵ ǵ Ǥ ǥ Ĝ ĝ Ǧ ǧ Ğ ğ Ģ ģ Ɠ ɠ Ġ ġ Ḡ ḡ Ꞡ ꞡ ᶃ

Ligatures and abbreviations

Computing codes

| Preview | G | g | ɡ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unicode name | LATIN CAPITAL LETTER G | LATIN SMALL LETTER G | LATIN SMALL LETTER SCRIPT G | |||

| Encodings | decimal | hex | dec | hex | dec | hex |

| Unicode | 71 | U+0047 | 103 | U+0067 | 609 | U+0261 |

| UTF-8 | 71 | 47 | 103 | 67 | 201 161 | C9 A1 |

| Numeric character reference | G |

G |

g |

g |

ɡ |

ɡ |

| EBCDIC family | 199 | C7 | 135 | 87 | ||

| ASCII 1 | 71 | 47 | 103 | 67 | ||

- 1 Also for encodings based on ASCII, including the DOS, Windows, ISO-8859 and Macintosh families of encodings.

Other representations

| NATO phonetic | Morse code |

| Golf |

|

|

| ||

| Signal flag | Flag semaphore | American manual alphabet (ASL fingerspelling) | British manual alphabet (BSL fingerspelling) | Braille dots-1245 Unified English Braille |

See also

References

- ^ The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. 1976.

- ^ Encyclopaedia Romana

- ^ Evertype.com

- ^ Hempl, George (1899). "The Origin of the Latin Letters G and Z". Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association. 30. The Johns Hopkins University Press: 24–41. doi:10.2307/282560. JSTOR 282560.

- ^ Association phonétique internationale (January 1895). "vɔt syr l alfabɛ" [Votes sur l'alphabet]. Le Maître Phonétique: 16–17.

- ^ Association phonétique internationale (February–March 1900a). "akt ɔfisjɛl" [Acte officiel]. Le Maître Phonétique: 20.

- ^ Jones, Daniel (July–December 1948). "desizjɔ̃ ofisjɛl" [Décisions officielles]. Le Maître Phonétique (90): 28–30.

- ^ International Phonetic Association (1993). "Council actions on revisions of the IPA". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 23 (1): 32–34. doi:10.1017/S002510030000476X.

- ^ International Phonetic Association (1949). The Principles of the International Phonetic Association. Department of Phonetics, University College, London. Supplement to Le Maître Phonétique 91, January–June 1949. Reprinted in Journal of the International Phonetic Association 40 (3), December 2010, pp. 299–358, doi:10.1017/S0025100311000089.

{{cite book}}: External link in|postscript=|postscript=at position 111 (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Wells, John C. (6 November 2006). "Scenes from IPA history". John Wells’s phonetic blog. Department of Phonetics and Linguistics, University College London.

- ^ International Phonetic Association (1999). Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A Guide to the Use of the International Phonetic Alphabet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 19. ISBN 0-521-63751-1.

- ^ Wong, Kimberly; Wadee, Frempongma; Ellenblum, Gali; McCloskey, Michael (2 April 2018). "The Devil's in the g-tails: Deficient letter-shape knowledge and awareness despite massive visual experience". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. doi:10.1037/xhp0000532. PMID 29608074.

- ^ Dean, Signe. "Most People Don't Know What Lowercase "G" Looks Like And We're Not Even Kidding". Science Alert. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ Constable, Peter (2004-04-19). "L2/04-132 Proposal to add additional phonetic characters to the UCS" (PDF).

- ^ Everson, Michael; et al. (2002-03-20). "L2/02-141: Uralic Phonetic Alphabet characters for the UCS" (PDF).

- ^ Everson, Michael; Dicklberger, Alois; Pentzlin, Karl; Wandl-Vogt, Eveline (2011-06-02). "L2/11-202: Revised proposal to encode "Teuthonista" phonetic characters in the UCS" (PDF).

External links

Media related to G at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to G at Wikimedia Commons The dictionary definition of G at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of G at Wiktionary The dictionary definition of g at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of g at Wiktionary- Lewis and Short Latin Dictionary: G