Margaret Gardner

Margaret Gardner | |

|---|---|

| |

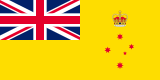

| 30th Governor of Victoria | |

| Assumed office 9 August 2023 | |

| Monarch | Charles III |

| Premier | Daniel Andrews Jacinta Allan |

| Lieutenant | James Angus |

| Preceded by | Linda Dessau |

| Vice-Chancellor of Monash University | |

| In office 1 September 2014 – 4 August 2023 | |

| Preceded by | Ed Byrne |

| Succeeded by | Sharon Pickering |

| Vice-Chancellor and President of the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology | |

| In office 4 April 2005 – 1 September 2014 | |

| Chancellor | Dennis Gibson Ziggy Switkowski |

| Preceded by | Ruth Dunkin |

| Succeeded by | Martin Bean |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 19 January 1954 Sydney, New South Wales, Australia |

| Spouse | Glyn Davis |

| Residence | Government House, Melbourne |

| Alma mater | University of Sydney |

| Profession | Economist |

| Salary | AU$485,000 as governor |

| Website | governor.vic.gov.au |

Margaret Elaine Gardner AC FASSA (born 19 January 1954[1][2]) is an Australian academic, economist and university executive serving as the 30th and current governor of Victoria since August 2023.[3] She was previously the vice-chancellor of Monash University from 2014 to 2023[4] and the president and vice-chancellor of RMIT University from 2005 to 2014.

Education

[edit]Gardner earned a Bachelor of Economics degree with first class honours from the University of Sydney and later a PhD with a thesis on Australian industrial relations.[citation needed]

After her PhD, Gardner received a Fulbright scholarship and studied at the University of California, Berkeley, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Cornell University.[5]

Career

[edit]Gardner has authored, co-authored and edited a number of texts in the fields of industrial relations and human resource management.[6] Between 1998 and 2002, as chair of two major Queensland Government taskforces, Gardner authored three government reviews: Queensland Industrial Relations Legislation, Pathways Articulation Through the Post-Compulsory Years of School to Further Education Training and Labour Market Participation.[citation needed]

Gardner served in executive positions with Deakin University, Griffith University and the Queensland University of Technology.[5]

Gardner was the deputy vice-chancellor of the University of Queensland.[5] She was appointed vice-chancellor of RMIT University on 4 April 2005, taking over from care-taker vice-chancellor Chris Whitaker. Prior to Gardner's appointment in 2005, RMIT was experiencing a regular budget shortfall of A$24 million.[7][8] After her first year as vice-chancellor, the university reported a $23.2 million surplus. This surplus increased to A$50.1 million by 2007. The change in financial situations was arranged through selling the university's real estate holdings, increasing student fees by 9% annually, and firing 180 university staff.[8][9]

Gardner was vice-chancellor of Monash University from September 2014 until August 2023 when she was appointed as Governor of Victoria. At the time of her retirement from Monash University, Gardner was Australia's highest paid vice-chancellor on nearly $1.6 million, up $190K on the year before.[10][11]

Gardner was the chair of Universities Australia from 2017 to 2019,[12] Chair of the Group of Eight (Australian universities) from 2020 to 2023, president of RMIT International University Holdings Pty. Ltd. and the Museum Board of Victoria, chair of the Australian Technology Network and of the Education Advisory Group of the Council for Australia-Latin America Relations, and director of the Australian Teaching and Learning Council.[13]

Governor of Victoria

[edit]On 5 June 2023, it was announced that Gardner would become the next governor of the state of Victoria, commencing on 9 August. Gardner replaced Linda Dessau, whose tenure ended at the end of June. In the interim, the Lieutenant-Governor of Victoria, James Angus, served as acting governor until Gardner's term commenced.[14]

Controversies

[edit]Sham redundancies

[edit]Gardner has a strong academic background in industrial relations. She has written widely on the subject including a 662 page tome: Employment relations : industrial relations and human resource management in Australia.[15] In 2011 whilst vice-chancellor of RMIT, Gardner overturned the findings of an internal RMIT redundancy review committee (RRC) and unlawfully terminated the employment of social sciences professor Judith Bessant. The RRC found that fair process had not been followed by the university and that there had been a failure of natural justice. Despite these findings, Gardner decided to proceed to make Bessant redundant.[citation needed]

On behalf of Bessant, the National Tertiary Education Union launched an "adverse action" claim against RMIT and Gardner in the Federal Court of Australia. The presiding judge, Justice Gray, was highly critical of Gardner's management of the case, especially given her considerable experience in industrial relations.[16] In deciding the case, Gray also said he took into consideration the "apparent determination" by Gardner to "ignore her knowledge of Professor Hayward's animosity towards Professor Bessant".[citation needed] He also found that Gardner displayed a lack of contrition for what the court found to be a blatant contravention of workplace laws.

The Federal Court reinstated Bessant and indicated that she would be entitled to approximately $2 million in compensation if she was not reinstated. The court also ordered RMIT to pay a civil penalty of $37,000 for two contraventions of the Fair Work Act 2009 as a warning to employers of the risks of using "sham" redundancies as a means for dismissing difficult employees. The case was reported in the national media in addition to becoming an important case study that is widely discussed on legal websites.[17][18][19][20] Bessant later published a personal account of the case.[21]

Wage theft

[edit]While Gardner was vice-chancellor and president of Australia's largest university, she presided over $8.6 million in underpayments to casual academic staff. Over six years, more than 2000 teachers had their rightful wages and entitlements withheld.[22] [23]

In 2022, Monash University and their lawyers Clayton Utz made an application to the Fair Work Commission to retrospectively rewrite clauses and vary the Monash University Enterprise Agreement.[24] They did this by trying to clarify use of the term "contemporaneous consultation" with students around lectures and tutorials. The university sought to have the enterprise agreement amended to define contemporaneous as meaning "within a week of the lecture". National Tertiary Education Union president Alison Barnes accused Monash of the "height of employer bastardry". She said that "They negotiated that enterprise bargaining agreement in good faith and to try to alter it is extraordinary."[25] If this had been successful, it would have resolved some of the university's underpayment liabilities and negated the National Tertiary Education Union (NTEU) underpayment claim. The Fair Work Commission's deputy president ultimately rejected the application by Monash University, ruling staff were entitled to the enterprise agreement they had agreed to in good faith.[26] [27][28][29]

On 23 September 2021, Gardner and the university unreservedly apologised to all staff and their NTEU representatives, later reiterating this apology before the Senate standing committee.[30]

Investments and conflicts of interest

[edit]In 2016, Gardner and her husband, Glyn Davis, the vice chancellor of the University of Melbourne, invested $166,000 in software company Vericus (developers of Cadmus) where their son, Rhys Davis, was chief technical officer.[31][32] Cadmus was a controversial new anti-cheating software that emerged out of a research project in 2015 before being developed and trialled by Vericus at the University of Melbourne. Cadmus received a substantial government grant under the now defunct Accelerating Commercialisation Grant scheme.[33] The University of Melbourne claimed Davis declared the conflict of interest and “rigorously excluded himself from any discussion of Cadmus matters”. Cadmus was later adopted widely by the university sector including the University of Melbourne.[34][35]

Farewell party

[edit]In 2023, Monash University threw a lavish $127,000 black-tie farewell party for Gardner at the National Gallery of Victoria.[36] When details of this were discovered through Freedom Of Information, it provoked outrage from university students and staff.[37] This took place at the same time as the university was facing a multimillion dollar wage theft claim from casual academics and the National Tertiary Education Union in the Federal Court of Australia.[38]

At the time of her retirement from Monash University, Gardner was Australia's highest paid vice-chancellor on nearly $1.6 million, up $190K on the year before.[39]

Honours

[edit]| Viceregal styles of Margaret Gardner (2023–present) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | Her Excellency the Honourable |

| Spoken style | Your Excellency |

- Orders

26 January 2020: Companion of the Order of Australia (AC) "For eminent service to tertiary education through leadership and innovation in teaching and learning, research and financial sustainability."[40]

26 January 2020: Companion of the Order of Australia (AC) "For eminent service to tertiary education through leadership and innovation in teaching and learning, research and financial sustainability."[40] 26 January 2007: Officer of the Order of Australia (AO) "For service to tertiary education, particularly in the areas of university governance and gender equity; and to industrial relations in Queensland".[41]

26 January 2007: Officer of the Order of Australia (AO) "For service to tertiary education, particularly in the areas of university governance and gender equity; and to industrial relations in Queensland".[41]

- Organisations

September 2018: Fellow of the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia.[42]

September 2018: Fellow of the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia.[42]

- Appointments

2023: Colonel of the Royal Victoria Regiment.

2023: Colonel of the Royal Victoria Regiment. 2023: Deputy Prior of the Order of St John.[43]

2023: Deputy Prior of the Order of St John.[43]

- Awards

Personal life

[edit]Gardner is married to Glyn Davis who is the secretary of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet in the Albanese government and was previously vice-chancellor of the University of Melbourne.[44] Between September-October 2024, Margaret visited the Harrow Bush Nursing Centre.

References

[edit]- ^ "Who is Glyn Davis Wife? Who is Margaret Gardner? Kids & Dating History - HIS Education". 12 December 2023.

- ^ "Index Ga-Gb".

- ^ "Premier Announces 30th Governor of Victoria". Governor of Victoria. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

- ^ Preiss, Benjamin (18 December 2013). "RMIT University vice-chancellor Margaret Gardner set to be first woman to lead Monash University". The Age.

- ^ a b c Professor Margaret Gardner, AO Archived 31 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine - RMIT University

- ^ Author: Gardner, Margaret Elaine - National Library of Australia

- ^ RMIT's new chief one of a vice-chancellor pair (David Rood) - The Age, 22 January 2005

- ^ a b Picking up the poisoned chalice (David Rood) - The Age, 9 April 2005

- ^ RMIT is back in the black Archived 19 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine (Lisa MacNamara) - The Australian, 2 May 2007.

- ^ "The uni rich list: Vice chancellors on $1 million salaries revealed" (Daniella White and Sherryn Groch), The Sydney Morning Herald, 30 June 2024.

- ^ "A crisis in university governance: Every Vice-Chancellors' salary, ranked". Honi Soit. 15 August 2022. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- ^ "Professor Margaret Gardner elected next chair of Universities Australia".

- ^ "Universities Australia".

- ^ Eddie, Rachel (5 June 2023). "'I'm a republican': Margaret Gardner named next governor of Victoria". The Age. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- ^ ”The National Library of Australia Catalogue”

- ^ "National Tertiary Education Union v Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology [2013] FCA 451". Federal Court of Australia. 16 May 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ^ "RMIT professor unfairly sacked". The Sydney Morning Herald. 19 May 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ^ "RMIT ordered to reinstate Professor Judith Bessant". The Australian. 21 May 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ^ "What a shame it's a sham". Hunt and Hunt. 8 October 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ^ "Sham Redundancies". Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ^ Margaret Thornton, ed. (2014). "'Smoking Guns': Reflections on Truth and Politics in the University" (PDF). Through a Glass Darkly: The Social Sciences Look at the Neoliberal University". Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ^ "Monash joins growing list of wage-theft universities" The Australian, 23 September 2021.

- ^ "The piece Monash Uni refused to publish on wage theft and Victoria's new governor" (Ben Eltham), 22 August 2023.

- ^ “Application by Monash University - (2023) FWC 611” (Justice Hatcher), Fair Work Commission, 15 March 2023.

- ^ "Monash tries to dodge $10m wage theft bill as uni sector wage crisis deepens" (Ben Schneiders), The Sydney Morning Herald, 14 April 2023.

- ^ "Fair Work Commission Decision-(2023) FWC 1148" (Deputy President Bell), Fair Work Commission, 7 June 2023.

- ^ "Monash University to settle $8,6 million pay shortfall with casual staff" (Cassandra Morgan), The Age, 23 September 2021.

- ^ "NTEU scores massive win over Monash's bid to dodge wage theft" (NTEU), 2022.

- ^ "Inside Australia's university wage theft machine" (Ben Schneiders), The Sydney Morning Herald, 15 April 2023.

- ^ "Systemic, sustained and shameful" (Senate standing committee on economics, Unlawful Underpayment of Employees Remuneration 4.32), March 2022.

- ^ "Campus News Briefing:Cadmus, Tastings, Safety" (Monique O'Rafferty), Farrago magazine, 20 August 2018.

- ^ "Uni chiefs defended on tech investment", The Herald Sun,

- ^ “Small business grants recipients 2016" (archive), [Wayback Machine]], 10 January 2006.

- ^ [1]

- ^ “University of Melbourne defends vice-chancellor Glyn Davis investing in anticheating software" The Herald Sun.

- ^ "This vice chancellor's farewell party cost $127,000. Staff not invited want answers" (Sherryn Groch), The Age, 5 March 2024.

- ^ "Lavish University party prompts urgent reform calls" (NTEU), 5 March 2024.

- ^ “Monash University criticised over $127,000 farewell party for vice-chancellor while students 'sit on floor'", The Guardian, 5 March 2024.

- ^ [https://www.smh.com.au/national/the-uni-rich-list-vice-chancellors-on-1-million-salaries-revealed-20240621-p5jnn6.html "The uni rich list: Vice chancellors on $1 million salaries revealed"" (Daniella White and Sherryn Groch), The Sydney Morning Herald, 30 June 2024.

- ^ "Professor Margaret Elaine GARDNER AO". Australian Honours Search Facility. Australian Government. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ 2007 Australia Day Honours: Media Notes Archived 27 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine - Office of the Governor-General of Australia

- ^ a b "Top scholars honoured: Academy of Social Sciences elects new fellows in 2018" (PDF). Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia. 26 September 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2018.

- ^ "Understanding the Most Venerable Order of St John" (PDF). Governor of New South Wales. 12 December 2014. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ^ "The thinking Australian's Posh and Becks" (David Cohen), The Guardian, 10 January 2006.

- 1954 births

- Living people

- University of Sydney alumni

- Australian economists

- Australian republicans

- Australian women economists

- Vice-chancellors of RMIT University

- Companions of the Order of Australia

- Officers of the Order of Australia

- Academic staff of Monash University

- Fellows of the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia

- Women heads of universities and colleges

- Governors of Victoria (Australia)