Gravity (2013 film): Difference between revisions

m Undid revision 591901428 by 140.239.203.243 (talk) it's a UK/US co production, |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 136: | Line 136: | ||

* When Kowalski unclips his tether and floats away to his death to save Stone from being pulled away from the ISS, several observers (including Plait and Tyson) contend that all Stone had to do was to give the tether a gentle tug, and Kowalski would have been safely pulled toward her, since the movie shows the pair having stopped and there would thus be no [[centrifugal force]] to pull Kowalski away.<ref name="BadAstronomy" /> |

* When Kowalski unclips his tether and floats away to his death to save Stone from being pulled away from the ISS, several observers (including Plait and Tyson) contend that all Stone had to do was to give the tether a gentle tug, and Kowalski would have been safely pulled toward her, since the movie shows the pair having stopped and there would thus be no [[centrifugal force]] to pull Kowalski away.<ref name="BadAstronomy" /> |

||

**Others, however, such as Kevin Grazier, science adviser for the movie, and NASA engineer Robert Frost, maintain that the pair are actually still decelerating, with Stone's leg caught in the parachute cords from the Soyuz. As the cords absorb her kinetic energy, they stretch. Kowalski's interpretation of the situation is that the cords are not strong enough to absorb his kinetic energy as well as hers, and that he must therefore release the tether in order to give her a chance of stopping before the cords fail and doom both of them.<ref>{{cite news|last=Dewey|first=Caitlin|title=Here’s what ‘Gravity’ gets right and wrong about space|url=http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/2013/10/21/heres-what-gravity-gets-right-and-wrong-about-space/|newspaper=Washington Post|date=October 21, 2013}}</ref> |

**Others, however, such as Kevin Grazier, science adviser for the movie, and NASA engineer Robert Frost, maintain that the pair are actually still decelerating, with Stone's leg caught in the parachute cords from the Soyuz. As the cords absorb her kinetic energy, they stretch. Kowalski's interpretation of the situation is that the cords are not strong enough to absorb his kinetic energy as well as hers, and that he must therefore release the tether in order to give her a chance of stopping before the cords fail and doom both of them.<ref>{{cite news|last=Dewey|first=Caitlin|title=Here’s what ‘Gravity’ gets right and wrong about space|url=http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/2013/10/21/heres-what-gravity-gets-right-and-wrong-about-space/|newspaper=Washington Post|date=October 21, 2013}}</ref> |

||

* Stone was shown not wearing [[Liquid Cooling and Ventilation Garment|liquid-cooled ventilation garments]] or even socks (always worn to protect against temperature extremes of space) under the EVA suit. Neither was she shown wearing [[Maximum Absorbency Garment|space diapers]].<ref name="ScottParazynski" /> |

* Stone was shown not wearing [[Liquid Cooling and Ventilation Garment|liquid-cooled ventilation garments]] or even socks (always worn to protect against temperature extremes of space) under the EVA suit. Neither was she shown wearing [[Maximum Absorbency Garment|space diapers]].<ref name="ScottParazynski" />• |

||

The most glaring inaccuracy, indeed impossibility, in the film is however the very premise upon which the plot is based; that is that multiple items, debris and space vehicles, can occupy the same orbit while travelling at different speeds (radial velocities.) This breaks Kepler’s third law of planetary motion which Newton’s law of gravitation showed applies to all orbiting bodies. [Newton supposed… that this relationship applied more generally than just to the Sun holding the planets.]<sup>1</sup> That is Tαa3/2 where ‘T’ is the orbital period and ‘a’ is the radius (semi major axis) of the orbit. As Richard Feynman put it, “…if the planets went in circles, as they nearly do, the time required to go around the circle would be proportional to the 2/3 power of the diameter (or radius).<sup>2</sup> Viz. objects in orbit at the same altitude travel at the same speed. |

|||

• Just as the period of a pendulum acting within the Earth’s gravity depends on the length of the tether (usually characterised as a massless rod in mechanics) and is independent of the mass of the bob (check this in any high school science book,) so the period of an orbiting body is dependent solely on its altitude in respect of the centre of gravity of, in this case, the Earth, and is independent of the mass of the satellite. It is just plausible that the debris of a destroyed satellite might cross the orbit of the shuttle in the film once, but it would thereafter shift into another orbit, reach escape velocity (unlikely) or fall to Earth. It is utterly impossible that it could maintain the same orbit travelling many thousands of kilometers an hour faster such that the debris passed around our protagonists every 90 minutes as stated in the film. |

|||

• Good science fiction should not contravene known physical laws. |

|||

<sup>1</sup> <ref>The Feynman Lectures on Physics vol 1, Chapter 7 page 3, Basic Books, New York 2005</ref>• <sup>2</sup> <ref>The Feynman Lectures on Physics vol 1, Chapter 7 page 2, Basic Books, New York 2005</ref> |

|||

[See also Wikipedia articles under the headings: Pendulum, Orbit, Geostationary Orbit and Kepler’s Laws of Planetary Motion] |

|||

* Stone's tears first roll down her face in zero gravity, and later are seen floating off her face. Without sufficient force to dislodge the tears, the tears would remain on her face due to [[surface tension]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.space.com/20597-how-astronauts-cry-space-video.html |title=How Astronauts Cry In Space (Video) |first=Chris |last=Hadfield |publisher=Space.com |date=April 11, 2013 |accessdate=October 22, 2013}}</ref> However, the movie does correctly portray the spherical appearance of liquid drops in a micro-gravity environment.<ref name="UCLA" /> |

* Stone's tears first roll down her face in zero gravity, and later are seen floating off her face. Without sufficient force to dislodge the tears, the tears would remain on her face due to [[surface tension]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.space.com/20597-how-astronauts-cry-space-video.html |title=How Astronauts Cry In Space (Video) |first=Chris |last=Hadfield |publisher=Space.com |date=April 11, 2013 |accessdate=October 22, 2013}}</ref> However, the movie does correctly portray the spherical appearance of liquid drops in a micro-gravity environment.<ref name="UCLA" /> |

||

Revision as of 20:25, 22 January 2014

| Gravity | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Alfonso Cuarón |

| Written by | Alfonso Cuarón Jonás Cuarón |

| Produced by | Alfonso Cuarón David Heyman |

| Starring | Sandra Bullock George Clooney |

| Cinematography | Emmanuel Lubezki |

| Edited by | Alfonso Cuarón Mark Sanger |

| Music by | Steven Price |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 90 minutes[2] |

| Countries | United Kingdom[1] United States[1] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $100 million[3] |

| Box office | $677,517,930[3] |

Gravity is a 2013 British-American 3D science-fiction thriller[3][4] and space drama film.[5][6] Directed, co-written, co-produced and co-edited by Alfonso Cuarón, the film stars Sandra Bullock and George Clooney as astronauts involved in the mid-orbit destruction of a space shuttle and their attempt to return to Earth.

Cuarón wrote the screenplay with his son Jonás and attempted to develop the project at Universal Studios. After the rights to the project were sold, the project found traction at Warner Bros. instead. The studio approached multiple actresses before casting Bullock in the female lead role. Robert Downey Jr. was also involved as the male lead before leaving the project and being replaced by Clooney. David Heyman, who previously worked with Cuarón on Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, produced the film with him. London-based VFX company Framestore spent over 3 years creating most of the visual effects for the entire movie encompassing over 80 minutes of screen time.

Gravity opened the 70th Venice International Film Festival in August 2013.[7] Its North American premiere was three days later at the Telluride Film Festival. It received a wide release in the United States and Canada on October 4, 2013. The film was met with universal acclaim from critics and audiences alike; both groups giving praise for Emmanuel Lubezki's cinematography, Steven Price's musical score, Cuarón's direction, Bullock's performance and visual effects.

In 2014, the film was nominated for 10 Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director (Alfonso Cuarón) and Best Actress (Sandra Bullock). The film also scored big at the 2014 Critics Choice Awards winning seven awards and a Golden Globe Award for Best Director.

Plot

The film is set during a fictitious Shuttle Explorer's STS-157 mission. Dr. Ryan Stone (Bullock) is a medical engineer on her first space shuttle mission aboard the Space Shuttle Explorer. She is accompanied by veteran astronaut Matt Kowalski (Clooney), who is commanding his final expedition. During a spacewalk to service the Hubble Space Telescope, Mission Control in Houston warns the team about a Russian missile strike on a defunct satellite, which has caused a chain reaction forming a cloud of space debris. Mission Control orders that the mission be aborted. Shortly after, communications with Mission Control are lost, though the astronauts continue to transmit, hoping that the ground crew can still hear them.

High-speed debris strikes the Explorer and detaches Stone from the shuttle, leaving her tumbling through space. Kowalski soon recovers Stone and they make their way back to the space shuttle. They discover that the shuttle has suffered catastrophic damage and the crew is dead. They use the thruster pack to make their way to the International Space Station (ISS), which is in orbit only about 900 m (2,950 ft) away. Kowalski estimates they have 90 minutes before the debris field completes an orbit and threatens them again.

En route to the ISS, the two discuss Stone's life back home and the death of her young daughter. As they approach the substantially damaged but still operational ISS, they see its crew has evacuated in one of its two Soyuz modules and that the parachute of the other capsule has accidentally been deployed, rendering it useless for returning to Earth. Kowalski suggests the remaining Soyuz be used to travel to the nearby Chinese space station Tiangong, 100 mi (160 km) away, and board one of its modules to return safely to Earth. Out of air and maneuvering power, the two try to grab onto the ISS as they fly by. Stone's leg gets entangled in Soyuz's parachute cords and she is able to grab a strap on Kowalski's suit. Despite Stone's protests, Kowalski detaches himself from the tether to save her from drifting away with him, and she is pulled back towards the ISS. As Kowalski floats away, he radios her additional instructions and encouragement.

Nearly out of oxygen, Stone manages to enter the ISS via an airlock but must hastily make her way to the Soyuz to escape a fire. As she maneuvers the capsule away from the ISS, the tangled parachute tethers prevent Soyuz from separating from the station. She spacewalks to release the cables, succeeding just as the debris field completes its orbit and destroys the station. Stone aligns the Soyuz with Tiangong but discovers the craft's engine has no fuel. After a brief radio communication with a Greenlandic Inuit fisherman and listening to him cooing a baby, Stone resigns herself to being stranded and shuts down the oxygen supply of the cabin in order to commit a painless suicide. As she begins to lose consciousness, Kowalski appears outside and enters the capsule. Scolding her for giving up, he tells her to rig the Soyuz's landing rockets to propel the capsule toward Tiangong. Stone then realizes that Kowalski's reappearance is in her imagination only, but has nonetheless given her new strength and the will to live on. She restores the flow of oxygen and uses the landing rockets to navigate toward Tiangong.

Unable to dock the Soyuz with the station, Stone ejects herself via explosive decompression and uses a fire extinguisher as a makeshift thruster to travel to Tiangong. Space debris knocks Tiangong from its trajectory, and it begins rapidly deorbiting. Stone enters the Shenzhou capsule just as Tiangong starts to break up on the upper edge of the atmosphere. As the capsule re-enters the Earth's atmosphere, Stone hears Mission Control over the radio tracking the capsule. It lands in a lake, but dense smoke due to an electrical fire inside the capsule forces Stone to evacuate immediately. Opening the capsule hatch allows water to rapidly fill the capsule, which sinks, forcing Stone to shed her spacesuit underwater and swim ashore. She takes her first shaky steps on land, in the full gravity of Earth.

Cast

- Sandra Bullock as Dr. Ryan Stone: A medical engineer and Mission Specialist on her first mission in space.

- George Clooney as Lieutenant Matt Kowalski: The commander of the team, Kowalski is a veteran astronaut planning to retire after the Explorer expedition. He enjoys telling stories about himself and joking with the team, but is also determined to protect the lives of his fellow astronauts.

- Ed Harris (voice) as Mission Control in Houston, Texas.

- Orto Ignatiussen (voice) as Aningaaq: A Greenlandic Inuit fisherman who intercepts one of Stone's transmissions. Aningaaq also appears in a self-titled short written and directed by Gravity co-writer Jonás Cuarón, which depicts the conversation between him and Stone from his perspective.[8]

- Paul Sharma (voice) as Shariff Dasari: The flight engineer on board the Explorer. Shariff has a wife and child and keeps a family photo on his suit.

- Amy Warren (voice) as Explorer captain.

- Basher Savage (voice) as International Space Station Captain

Themes

Despite being set in outer space, the film draws upon motifs from shipwreck and wilderness survival stories about psychological change and resilience in the aftermath of catastrophe.[9][10][11][12] Cuarón uses Stone to illustrate clarity of mind, persistence, training, and improvisation in the face of isolation and the mortal consequences of a relentless Murphy's Law.[4]

The film incorporates spiritual themes both in terms of Ryan's daughter's accidental death, the will to survive in the face of overwhelming odds, as well as the impossibility of rescue.[10] Calamities unfold but there are no witnesses to them, save for the surviving astronauts.[13]

The impact of scenes is heightened by alternating between objective and subjective perspectives, the warm face of the planet and the depths of dark space, the chaos but also predictability of the deadly debris field, and silence of the vacuum of space with the sound of the score.[12][14] The film uses very long and uninterrupted shots throughout to draw the audience into the action but also contrasts these with claustrophobic shots within space suits and capsules.[10][15]

Some commentators have noted religious themes in the film.[16][17][18][19] For instance, Catholic author Fr. Robert Barron summarizes the tension between Gravity's technology and religious symbolism, "The technology which this film legitimately celebrates... can’t save us, and it can’t provide the means by which we establish real contact with each other. The Ganges in the sun, the St. Christopher icon, the statue of Budai, and above all, a visit from a denizen of heaven, signal that there is a dimension of reality that lies beyond what technology can master or access... the reality of God".[19]

Human evolution and the resilience of life may also be seen as a key theme of the movie.[20][21][22][23] The movie opens with the hitherto climax of human civilisation, the exploration of space, and ends with an allegory to the dawn of mankind, when Dr. Ryan Stone (Bullock) fights her way out of the ocean after the crash-landing, passing an amphibian, grabbing the soil of the shore and slowly regaining her capacity to stand upright and walk. In an interview director Cuarón notes: "She’s in these murky waters almost like an amniotic fluid or a primordial soup. In which you see amphibians swimming. She crawls out of the water, not unlike early creatures in evolution. And then she goes on all fours. And after going on all fours she’s a bit curved until she is completely erect. It was the evolution of life in one, quick shot".[21] Other imagery depicting the formation of life include a scene in which Dr. Ryan Stone rests in an embryonic position, surrounded with a rope strongly resembling an umbilical cord. Dr. Ryan Stone's return from space, accompanied by meteorite-like debris, may be seen as a hint that elements essential to the development of life on earth may have come from outer space in form of meteorites.[24]

Production

Development

Alfonso Cuarón wrote the screenplay with his son Jonás and attempted to develop the project at Universal Pictures, where it stayed in development for several years. After the rights to the project were sold, the project found traction at Warner Bros. instead. Warner Bros. acquired the project, which in February 2010, attracted the attention of Angelina Jolie, who had rejected a sequel to Wanted.[25] Later in the month, she passed on the project,[26] partially because the studio did not want to pay the $20 million fee[27] she had received for her latest two movies, but also because she wanted to work on directing her Bosnian war film In the Land of Blood and Honey.[28] In March, Robert Downey, Jr. entered talks to be cast in the male lead role.[29]

In mid-2010, Marion Cotillard tested for the female lead role. By August 2010, Scarlett Johansson and Blake Lively were in the running for the role.[27] In September, Cuarón received approval from Warner Bros. to offer the role without a screen test to Natalie Portman, who was being praised for her performance in the then-recently released Black Swan.[30] Portman passed on the project due to scheduling conflicts, and Warner Bros. then approached Sandra Bullock for the role.[28] In November 2010, Downey left the project to star in How to Talk to Girls, a project in development with Shawn Levy attached to direct.[31] The following December, with Bullock signed for the co-lead role, George Clooney replaced Downey.[32]

A big challenge for the team was the question of how to shoot long takes in a zero-g environment. Eventually the team decided to use computer-generated imagery for the spacewalk scenes, and automotive robots to move Bullock's character for interior space station scenes.[33] This meant that shots and blocking had to be planned well in advance in order for the robots to be programmed.[33]

Filming

Gravity had a production budget of $100 million and was filmed digitally on multiple Arri Alexas. Principal photography on the film began in late May 2011.[34] Live elements were shot at Pinewood and Shepperton Studios in the United Kingdom.[35] The landing scene was filmed at Lake Powell, Arizona (incidentally where the astronauts' landing scene was filmed in Planet of the Apes).[36] Visual effects were supervised by Tim Webber at the London-based VFX company Framestore which was responsible for creating most of the visual effects for the entire movie except for 17 shots. Framestore was also heavily involved in the Art Direction and Previz along with The Third Floor. Tim Webber stated that 80 percent of the movie consisted of CG while in comparison James Cameron's Avatar had a percentage of 60.[37] To simulate the authenticity and reflection of unfiltered light in space, a manually controlled lighting system consisting of 1.8 million individually controlled LED lights was built.[38] The 3D was designed and supervised by Chris Parks. The majority of the 3D was created through stereo rendering the CG at Framestore with the rest converted into 3D in post production, principally at Prime Focus, London with additional conversion work by Framestore. Prime Focus's supervisor was Richard Baker. Filming began in London in May 2011.[39] The film contains only 156 or so shots, with an average shot length of 45 seconds, resulting in fewer and longer shots than in most films of this length.[40] Although the first trailer had audible explosions and other sounds, in the final film these scenes are silent. Cuarón said, "They put in explosions [in the trailer]. As we know, there is no sound in space. In the film, we don't do that."[41] The soundtrack in the film's space scenes is populated only by the musical score and sounds astronauts would hear in their suits or the space vehicles.

Most of Bullock's shots were done with her inside of a giant mechanical rig.[33] Getting into the rig took a significant amount of time, so Bullock opted to stay in it for up to 10 hours a day, communicating with others only through a headset.[33] Cuarón said his biggest challenge was to make the set feel as inviting and non-claustrophobic as possible. The team attempted to do this by having a massive celebration when Bullock arrived each day. They also nicknamed the rig "Sandy's cage" and gave it a lighted sign reflecting this.[33]

The majority of the movie was shot digitally using Arri Alexa Classics cameras equipped with wide Arri Master Prime lenses. However the final scene of the film which takes place on Earth was shot on an Arri 765 camera on 65mm film in order to provide the sequence a visual contrast compared to the rest of the picture.[42]

Music

Steven Price composed the incidental music to Gravity. In early September 2013, a 23-minute preview of the soundtrack was released online.[43] A soundtrack album was released digitally on September 17, 2013, and in physical formats on October 1, 2013, by WaterTower Music.[44] Additional songs featured in the film include:[45]

- "Angels Are Hard to Find" by Hank Williams, Jr.

- "Sinigit Meerannguaq" by Juaaka Lyberth

- "Destination Anywhere" by Chris Benstead and Robin Baynton

- "922 Anthem" by 922 (feat. Gaurav Dayal)

- "Ready" by Charles Scott (feat. Chelsea Williams)

In most of the film's official trailers, Spiegel im Spiegel was used, written by Estonian composer Arvo Pärt in 1978.[46]

Release

Gravity was released in 3D and IMAX 3D on October 4, 2013.[47] The film's release coincided with the beginning of World Space Week, observed from October 4 to 10. The film was originally scheduled to be released on November 21, 2012, before being re-scheduled for a 2013 release in order to complete extensive post-production effects work.[48]

Box office

As of January 20, 2014, Gravity has grossed $258,717,930 in North America, and $418,800,000 in other countries, for a worldwide total of $677,517,930, making it the eighth highest grossing film of 2013.[3]

Preliminary reports had the film tracking for a debut of over $40 million in North America.[49][50] The film earned $1.4 million from its Thursday night showings,[51] and reached a $17.5 million Friday total.[52] It topped the box office and also went on to break Paranormal Activity 3's record as the biggest October and autumn openings ever, as the film brought in $55.8 million.[53] Of the film's opening weekend gross, 80 percent of the total was derived from its 3D showings for a sum of $44 million—which also includes $11.2 million, or 20 percent of the total receipts, from IMAX 3D showings, the highest percentage ever for a film opening more than $50 million.[54] The movie retained the top spot at the box office during its second and third weekends.[55][56] Gravity opened at number one in the United Kingdom at £6.23 million over the first weekend of release[57] and remained at the top spot for the second week running.[58]

Critical reception

Gravity had its world premiere at the 70th Venice International Film Festival on August 28, where it received universal acclaim from critics and audiences, praising the acting, direction, screenplay, cinematography, visual effects, production design, the use of 3D, and Steven Price's musical score.[59] Film review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes reports that 97% of critics gave the film a positive review based on 294 reviews with a "Certified Fresh" rating, with an average score of 9.1/10. The site's consensus states: "Alfonso Cuarón's Gravity is an eerie, tense sci-fi thriller that's masterfully directed and visually stunning."[60] On Metacritic, which assigns a normalised rating out of 100 based on reviews from critics, the film has a score of 96 (citing "universal acclaim") based on 49 reviews.[61] CinemaScore polls conducted during the opening weekend revealed the average grade cinemagoers gave Gravity was A- on an A+ to F scale.[54]

Matt Zoller Seitz, writing on RogerEbert.com, gave the film a maximum four stars, stating that "Alfonso Cuarón's Gravity, about astronauts coping with disaster, is a huge and technically dazzling film and that the film's panoramas of astronauts tumbling against starfields and floating through space station interiors are at once informative and lovely."[62] At Variety, Justin Chang posits that the film "restores a sense of wonder, terror and possibility to the big screen that should inspire awe among critics and audiences worldwide."[63] Richard Corliss of Time proclaimed that "Cuarón shows things that cannot be but, miraculously, are, in the fearful, beautiful reality of the space world above our world. If the film past is dead, Gravity shows us the glory of cinema's future. It thrills on so many levels. And because Cuarón is a movie visionary of the highest order, you truly can't beat the view." He also praised Cuarón for "[playing] daringly and dexterously with point-of-view: at one moment you're inside Ryan's helmet as she surveys the bleak silence, then in a subtle shift you're outside to gauge her reaction. The 3-D effects, added in post-production, provide their own extraterrestrial startle: a hailstorm of debris hurtles at you, as do a space traveler's thoughts at the realization of being truly alone in the universe."[64]

Peter Travers of Rolling Stone gave the film four out of four stars, stating that the film was "more than a movie. It's some kind of miracle."[65] A. O. Scott, writing for The New York Times highlighted the use of 3-D "which surpasses even what James Cameron accomplished in the flight sequences of Avatar." Scott went on to say that the film "in a little more than 90 minutes rewrites the rules of cinema as we have known them." [66]

Critics have also compared Gravity with other notable movies set in space. The choice of Ed Harris as the voice of Mission Control is seen as a nod to Apollo 13.[67] Other references include Alien,[14] and WALL-E.[68]

The film was praised by James Cameron himself, who stated, "I think it's the best space photography ever done, I think it's the best space film ever done, and it's the movie I've been hungry to see for an awful long time".[69] Quentin Tarantino named it one of his top ten movies of 2013.[70]

Empire, Time and Total Film ranked the film as the best of 2013.[71][72][73] It was also the highest-rated film of the year on IMDb.[74]

Accolades

Gravity received ten nominations at the 86th Academy Awards, the most nominations of this year's ceremony tied with American Hustle. The nominations includes Best Picture, Best Director for Cuarón, Best Actress for Bullock, and Best Original Score for Price, among others.[75]

Alfonso Cuarón won the Golden Globe Award for Best Director, and the film was further nominated for Best Motion Picture – Drama, Best Actress in Drama for Bullock and Best Original Score.[76]

It received eleven nominations at the 67th British Academy Film Awards, more than any other film of 2013, including Best Film, Outstanding British Film, Best Director, Best Original Screenplay, and Best Actress in a Leading Role. Including his nominations as producer (for Best Film awards) and editor, Cuarón was also the person with the most nominations, with five overall.[77][78]

Scientific accuracy

Cuarón has stated that the film is not always scientifically accurate and that some liberties were needed to sustain the story.[79] "This is not a documentary," Cuarón said. "It is a piece of fiction."[80]

Nevertheless, the film has been praised for the realism of its premises and its overall adherence to physical principles, despite a number of inaccuracies and exaggerations.[81][82][83] According to NASA Astronaut Michael J. Massimino, who took part in two Hubble Space Telescope (HST) Servicing Missions (STS-109 and STS-125), "nothing was out of place, nothing was missing. There was a one-of-a-kind wirecutter we used on one of my spacewalks and sure enough they had that wirecutter in the movie."[84] Astronaut Buzz Aldrin called the visual effects "remarkable". He adds, "I was so extravagantly impressed by the portrayal of the reality of zero gravity. Going through the space station was done just the way that I've seen people do it in reality. The spinning is going to happen—maybe not quite that vigorous—but certainly we've been fortunate that people haven't been in those situations yet. I think it reminds us that there really are hazards in the space business, especially in activities outside the spacecraft."[85] Garrett Reisman, a former NASA astronaut, noted that, "The pace and story was definitely engaging and I think it was the best use of the 3-D IMAX medium to date. Rather than using the medium as a gimmick, 'Gravity' uses it to depict a real environment that is completely alien to most people. But the question that most people want me to answer is, how realistic was it? The very fact that the question is being asked so earnestly is a testament to the verisimilitude of the movie. When a bad science fiction movie comes out, no one bothers to ask me if it reminded me of the real thing."[86]

On the other hand, astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson, astronomer and skeptic Phil Plait, and veteran NASA astronaut and spacewalker Scott E. Parazynski have offered comments about some of the most "glaring" inaccuracies.[83][87][88] Examples of such mistakes include:

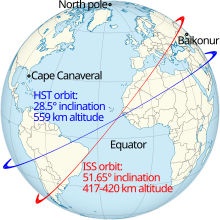

- The HST, which is being repaired at the beginning of the movie, has an altitude of about 559 kilometers (347 mi), and an orbital inclination of 28.5 degrees. The ISS has an altitude of around 420 kilometers (260 mi), and an orbital inclination of 51.65 degrees. With such significant differences in orbital parameters, it would be impossible to travel between them without precise preparation, planning, calculation, appropriate technology and a large amount of fuel.[82][83][88]

- When Kowalski unclips his tether and floats away to his death to save Stone from being pulled away from the ISS, several observers (including Plait and Tyson) contend that all Stone had to do was to give the tether a gentle tug, and Kowalski would have been safely pulled toward her, since the movie shows the pair having stopped and there would thus be no centrifugal force to pull Kowalski away.[88]

- Others, however, such as Kevin Grazier, science adviser for the movie, and NASA engineer Robert Frost, maintain that the pair are actually still decelerating, with Stone's leg caught in the parachute cords from the Soyuz. As the cords absorb her kinetic energy, they stretch. Kowalski's interpretation of the situation is that the cords are not strong enough to absorb his kinetic energy as well as hers, and that he must therefore release the tether in order to give her a chance of stopping before the cords fail and doom both of them.[89]

- Stone was shown not wearing liquid-cooled ventilation garments or even socks (always worn to protect against temperature extremes of space) under the EVA suit. Neither was she shown wearing space diapers.[83]•

The most glaring inaccuracy, indeed impossibility, in the film is however the very premise upon which the plot is based; that is that multiple items, debris and space vehicles, can occupy the same orbit while travelling at different speeds (radial velocities.) This breaks Kepler’s third law of planetary motion which Newton’s law of gravitation showed applies to all orbiting bodies. [Newton supposed… that this relationship applied more generally than just to the Sun holding the planets.]1 That is Tαa3/2 where ‘T’ is the orbital period and ‘a’ is the radius (semi major axis) of the orbit. As Richard Feynman put it, “…if the planets went in circles, as they nearly do, the time required to go around the circle would be proportional to the 2/3 power of the diameter (or radius).2 Viz. objects in orbit at the same altitude travel at the same speed.

• Just as the period of a pendulum acting within the Earth’s gravity depends on the length of the tether (usually characterised as a massless rod in mechanics) and is independent of the mass of the bob (check this in any high school science book,) so the period of an orbiting body is dependent solely on its altitude in respect of the centre of gravity of, in this case, the Earth, and is independent of the mass of the satellite. It is just plausible that the debris of a destroyed satellite might cross the orbit of the shuttle in the film once, but it would thereafter shift into another orbit, reach escape velocity (unlikely) or fall to Earth. It is utterly impossible that it could maintain the same orbit travelling many thousands of kilometers an hour faster such that the debris passed around our protagonists every 90 minutes as stated in the film.

• Good science fiction should not contravene known physical laws.

[See also Wikipedia articles under the headings: Pendulum, Orbit, Geostationary Orbit and Kepler’s Laws of Planetary Motion]

- Stone's tears first roll down her face in zero gravity, and later are seen floating off her face. Without sufficient force to dislodge the tears, the tears would remain on her face due to surface tension.[92] However, the movie does correctly portray the spherical appearance of liquid drops in a micro-gravity environment.[82]

Despite the inaccuracies in Gravity, Tyson, Plait and Parazynski have all said they enjoyed watching the film.[83][87][88] Aldrin hoped that the film would stimulate the public to find an interest in space again, after decades of diminishing investments into advancements in the field.[85]

See also

- Apollo 13, a 1995 film dramatizing the Apollo 13 incident

- Kessler syndrome

- List of films featuring space stations

- Love, a 2011 film about being stranded in space

- Marooned, 1969 film about survival in space

- Mercury-Redstone 4#Splashdown, a Mercury capsule that sank after splashdown

- Survival film

References

- ^ a b "Gravity". Toronto International Film Festival.

- ^ "GRAVITY (12A)". Warner Bros. British Board of Film Classification. August 23, 2013. Retrieved August 23, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Staff (January 16, 2014). "Gravity". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- ^ a b Berardinelli, James (October 3, 2013). "Gravity – A Movie Review". ReelViews. Retrieved October 7, 2013.

- ^ Chris Lackner (September 27, 2013). "Pop Forecast: Gravity is gripping space drama and it's gimmick free". The Vancouver Sun. Retrieved October 3, 2013.

- ^ "Girl on a wire: Sandra Bullock talks about her new space drama, Gravity". South China Morning Post. Retrieved October 3, 2013.

- ^ "George Clooney and Sandra Bullock to open Venice film festival". BBC News.

- ^ "La Biennale di Venezia – Aningaaq". LaBiennale.org.

- ^ Zoller Seitz, Matt (October 4, 2013). "Review: Gravity". RogerEbert.com.

- ^ a b c "Gravity". The Miami Herald. October 3, 2013.

- ^ Hornaday, Ann (October 3, 2013). ""Gravity" works as both thrilling sci-fi spectacle and brilliant high art". The Washington Post.

- ^ a b Scott, A.O. (October 3, 2013). "Between Earth and Heaven". The New York Times.

- ^ LaSalle, Mick (October 4, 2013). ""Gravity" review: powerful images – and drama". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ a b McCarthy, Todd (August 28, 2013). "Gravity: Venice Review". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (October 3, 2013). "Review: "Gravity" has powerful pull thanks to Sandra Bullock, 3-D". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Weiss, Jeffrey (October 8, 2013). "'Gravity' film Philosophizes About Existence for the 'Nones'". The Huffington Post. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ^ O'Neil, Tyler (October 9, 2013). "Christian Reviewers Call New Film 'Gravity' an Allegory for God, Jesus". Christian Post. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ^ Barron, Robert (October 8, 2013). Gravity: A Commentary. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ^ a b Barron, Robert (October 17, 2013). "Gravity opens the door to the reality of God". The Catholic Register. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ^ Woerner, Meredith. "Gravity's ending holds a deeper meaning, says Alfonso Cuaron". io9.

- ^ a b http://www.giantfreakinrobot.com/scifi/alfonso-cuarn-talks-gravitys-visual-metaphors-george-clooney-clarifies-writing-credit.html

- ^ http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2013/10/08/alfonso-cuaron-explains-the-darwinian-ending-of-gravity.html

- ^ http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/gravity-2013

- ^ http://www.spiegel.de/wissenschaft/weltall/meteorit-sutter-s-mill-lieferte-kohlenstoff-verbindungen-a-921410.html

- ^ Brodesser-Akner, Claude (February 25, 2010). "Angelina Jolie Says No to Wanted 2, Killing the Sequel". Vulture. New York. New York Media. Retrieved April 27, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) - ^ Sperling, Nicole (February 26, 2010). "Angelina Jolie out of 'Wanted 2': Follow-up project not a lock". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved April 27, 2013.

- ^ a b Kit, Borys (August 11, 2010). "Blake Lively, Scarlett Johansson vie for sci-fi film". Reuters. Thomson Reuters.

- ^ a b Kroll, Justin (October 6, 2010). "Sandra Bullock in talks for 'Gravity'". Variety. Retrieved April 27, 2013.

- ^ Rosenberg, Adam (April 27, 2013). "Robert Downey Jr. In Talks To Star In 'Children Of Men' Director Alfonso Cuaron's 'Gravity'". MTV. Viacom Media Networks.

- ^ Fernandez, Jay A. (September 8, 2010). "Natalie Portman offered lead in 3D survival story". Reuters. Thomson Reuters. Retrieved April 27, 2013.

- ^ Kit, Borys (November 17, 2010). "EXCLUSIVE: Robert Downey Jr. Eyeing 'How to Talk to Girls'". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved April 27, 2013.

- ^ McNary, Dave (December 16, 2010). "Clooney to replace Downey Jr. in 'Gravity'". Variety. Retrieved April 27, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Cohen, David S; McNary, David (September 3, 2013). "Alfonso Cuaron Returns to the Bigscreen After Seven Years With 'Gravity'". Variety. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

- ^ Fitzmaurice, Sarah (June 9, 2011). "Feeling broody? George Clooney gets snap happy with Sandra Bullock and her son Louis on set of new film". Daily Mail. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

- ^ "Gravity | Pinewood filming locations". Pinewood Group. Pinewood Studios. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

- ^ "What Is The Mind Blowing Connection Between GRAVITY And PLANET OF THE APES?". badass digest. Retrieved November 26, 2013.

- ^ "Gravity". Framestore. Retrieved October 22, 2013.

- ^ Tech Breakthroughs in Film: From House of Wax to Gravity

- ^ Dang, Simon (April 17, 2011). "Producer David Heyman Says Alfonso Cuarón's 3D Sci-Fi Epic 'Gravity' Will Shoot This May". The Playlist. IndieWire. Retrieved April 27, 2013.

- ^ Raup, Jordan. "Alfonso Cuaron's 2-Hour 'Gravity' Revealed; 17-Minute Opening Take Confirmed". The Film Stage. Retrieved November 18, 2013.

- ^ Child, Ben (July 22, 2013). "Comic-Con 2013: five things we learned". The Guardian. Retrieved July 22, 2013.

- ^ "Emmanuel Lubezki, ASC, AMC and his collaborators detail their work on Gravity, a technically ambitious drama set in outer space". The American Society of Cinematographers. November 2013. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- ^ "'Gravity' Soundtrack Preview Highlights 23 Minutes Of Steven Price's Nerve-Rattling Score". Huffington Post. September 5, 2013. Retrieved September 8, 2013.

- ^ "'Gravity' Soundtrack Details". Film Music Reporter. August 28, 2013. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ "Gravity (2013) – Song Credits". Soundtrack.net. Retrieved October 7, 2013.

- ^ Wickman, Forrest (May 9, 2013). "Trailer Critic: Alfonso Cuarón's Gravity". Slate. Retrieved May 12, 2013.

- ^ "UPDATE: Warner Bros. and IMAX Sign Up to 20 Picture Deal!". ComingSoon.net. CraveOnline. April 25, 2010. Retrieved August 17, 2011.

- ^ Vary, Adam (May 14, 2012). "Sandra Bullock, George Clooney sci-fi drama 'Gravity' moved to 2013". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved May 15, 2012.

- ^ Stewart, Andrew (October 4, 2013). "Box Office: 'Gravity' Tracking for a $40 Mil-Plus Bow With Record 3D Sales". Variety. Penske Media Corporation. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

- ^ Smith, Grady (October 3, 2013). "Box office preview: 'Gravity' headed for a stellar debut". Entertainment Weekly. CNN. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

- ^ McClintock, Pamela (October 4, 2013). "Box Office: 'Gravity' Takes Flight With $1.4 Million Thursday Night". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

- ^ Mendelson, Scott (October 5, 2013). "Friday Box Office: 'Gravity' Earns $17.5m, Rockets Towards i love it $50m". Forbes. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

- ^ Subers, Ray (October 7, 2013). "Weekend Report: Houston, 'Gravity' Does Not Have a Problem". Box Office Mojo. Amazon.com. Retrieved October 7, 2013.

- ^ a b Cunninghham, Todd (October 6, 2013). "'Gravity' soars to record-breaking box-office blast-off". MSN Entertainment. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

- ^ Subers, Ray (October 13, 2013). "Weekend Report: 'Gravity' Holds, 'Captain' Floats, 'Machete' Bombs". Box Office Mojo. Amazon.com. Retrieved January 17, 2014.

- ^ Subers, Ray (October 20, 2013). "Weekend Report: 'Gravity' Wins Again, 'Carrie' Leads Weak Newcomers". Box Office Mojo. Amazon.com. Retrieved January 17, 2014.

- ^ "Space thriller Gravity takes £6.23 million at UK box office on opening weekend". Evening Standard. January 16, 2014

- ^ http://www.screendaily.com/box-office/gravity-stays-top-of-uk-box-office/5063747.article

- ^ Trumbore, Dave (August 28, 2013). "GRAVITY Reviews Praise Sandra Bullock and George Clooney's Performances". Collider. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- ^ "Gravity". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved September 19, 2013.

- ^ "Gravity Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved September 19, 2013.

- ^ "Gravity review". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013. Retrieved October 7, 2013.

- ^ Frater, Patrick (August 14, 2013). "'Gravity' Review: Alfonso Cuaron's White-Knuckle Space Odyssey". Variety. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- ^ "Gravity at the Venice Film Festival: Dread and Awe in Space". Time. August 28, 2013. Retrieved October 2, 2013.

- ^ Travers, Peter. "Gravity". Rolling Stone. Retrieved November 20, 2013.

- ^ Scott, A.O. "Between Earth and Heaven". The New York Times. Retrieved November 20, 2013.

- ^ Weber, Lindsey (October 6, 2013). "Did You Catch Gravity's Apollo 13 Shout-out?". Vulture. Retrieved October 7, 2013.

- ^ Morgenstern, Joe (October 3, 2013). ""Gravity" Exerts Cosmic Pull". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "Alfonso Cuaron Returns to the Bigscreen After Seven Years With 'Gravity'". Variety. September 3, 2013. Retrieved September 5, 2013.

- ^ "Quentin Tarantino's Top 10 Films of 2013 – SO FAR". The Quentin Tarantino Archives. October 5, 2013. Retrieved October 7, 2013.

- ^ "The 50 Best Films of 2013". Empire. December 3, 2013. Retrieved December 4, 2013.

- ^ "Top 10 Best Movies". Time. December 4, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Best movies of 2013 - TotalFilm.com". Total Film. December 11, 2013.

- ^ "IMDb - Year in Review - Top 10 Highest-Rated Films of 2013". IMDb. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- ^ "2014 Oscar Nominees". AMPAS. January 16, 2014. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- ^ "Golden Globe Awards 2014: Nominees Announced For 71st Annual Golden Globes". The Huffington Post. December 12, 2013. Retrieved December 12, 2013.

- ^ "2013 Nominations" (PDF). BAFTA. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ "Bafta Film Awards 2014: Full list of nominees". BBC News. January 8, 2014. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ "Gravity". Space.com.

- ^ Lisa Respers France (October 8, 2013). "5 things that couldn't happen in 'Gravity'". CNN.com. Retrieved November 25, 2013.

- ^ "What's behind the science of 'Gravity'?". CNN. September 28, 2013. Retrieved October 2, 2013.

- ^ a b c Margot, Jean-Luc (September 28, 2013). "How realistic is 'Gravity'?". UCLA. Retrieved October 8, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Watkins, Gwynne (October 8, 2013). "An Astronaut Fact-checks Gravity". Vulture. Retrieved October 12, 2013.

- ^ "Gravity: Ripped from the Headlines?". Space Safety Magazine. October 3, 2013. Retrieved October 3, 2013.

- ^ a b "'Gravity' Review by Astronaut Buzz Aldrin". The Hollywood Reporter. October 3, 2013. Retrieved October 7, 2013.

- ^ Reisman, Garrett. "What Does A Real Astronaut Think Of 'Gravity'?". Forbes. Retrieved October 20, 2013.

- ^ a b "Astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson Fact-Checks Gravity on Twitter". Wired. October 7, 2013. Retrieved October 8, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Plait, Phil (October 4, 2013). "Bad Astronomy Movie Review: Gravity". Slate. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- ^ Dewey, Caitlin (October 21, 2013). "Here's what 'Gravity' gets right and wrong about space". Washington Post.

- ^ The Feynman Lectures on Physics vol 1, Chapter 7 page 3, Basic Books, New York 2005

- ^ The Feynman Lectures on Physics vol 1, Chapter 7 page 2, Basic Books, New York 2005

- ^ Hadfield, Chris (April 11, 2013). "How Astronauts Cry In Space (Video)". Space.com. Retrieved October 22, 2013.

External links

- Official website

- Gravity at IMDb

- Gravity at AllMovie

- Gravity at Box Office Mojo

- Please use a more specific Metacritic template.

- Gravity at Rotten Tomatoes

- 2013 films

- 2013 3D films

- 2010s drama films

- 2010s science fiction films

- 2010s thriller films

- American films

- American 3D films

- American drama films

- American science fiction films

- American thriller films

- British films

- British 3D films

- British drama films

- British science fiction films

- British thriller films

- English-language films

- Films directed by Alfonso Cuarón

- Films shot digitally

- Films shot in 70mm

- Films shot in Arizona

- Films shot in London

- Films shot in Surrey

- Films shot from the first-person perspective

- Greenlandic-language films

- IMAX films

- Dolby Atmos films

- Dolby Surround 7.1 films

- Heyday Films films

- Warner Bros. films