Hanford Site

46°38′51″N 119°35′55″W / 46.64750°N 119.59861°W

The Hanford Site is a mostly decommissioned nuclear production complex operated by the United States federal government on the Columbia River in the U.S. state of Washington. The site has been known by many names, including: Hanford Project, Hanford Works, Hanford Engineer Works and Hanford Nuclear Reservation. Established in 1943 as part of the Manhattan Project in Hanford, south-central Washington, the site was home to the B Reactor, the first full-scale plutonium production reactor in the world.[1] Plutonium manufactured at the site was used in the first nuclear bomb, tested at the Trinity site, and in Fat Man, the bomb detonated over Nagasaki, Japan.

During the Cold War, the project expanded to include nine nuclear reactors and five large plutonium processing complexes, which produced plutonium for most of the more than 60,000 weapons in the U.S. nuclear arsenal.[2][3] Nuclear technology developed rapidly during this period, and Hanford scientists produced major technological achievements. Many early safety procedures and waste disposal practices were inadequate, and government documents have confirmed that Hanford's operations released significant amounts of radioactive materials into the air and the Columbia River.

The weapons production reactors were decommissioned at the end of the Cold War, and decades of manufacturing left behind 53 million US gallons (200,000 m3) of high-level radioactive waste[4] stored within 177 storage tanks, an additional 25 million cubic feet (710,000 m3) of solid radioactive waste, and 200 square miles (520 km2) of contaminated groundwater beneath the site.[5] In 2011, DOE emptied 149 single-shell tanks by pumping nearly all of the liquid waste out into 28 newer double-shell tanks. DOE later found water intruding into at least 14 single-shell tanks and that one of them had been leaking about 640 US gallons (2,400 L; 530 imp gal) per year into the ground since about 2010. In 2012, DOE discovered a leak also from a double-shell tank caused by construction flaws and corrosion in the bottom, and that 12 double-shell tanks have similar construction flaws. Since then, DOE changed to monitoring single-shell tanks monthly and double-shell tanks every 3 years, and also changed monitoring methods. In March 2014, DOE announced further delays in the construction of the Waste Treatment Plant, which will affect the schedule for removing waste from the tanks.[6] Intermittent discoveries of undocumented contamination have slowed the pace and raised the cost of cleanup.[7]

In 2007, the Hanford site represented two-thirds of the nation's high-level radioactive waste by volume.[8] Hanford is currently the most contaminated nuclear site in the United States[9][10] and is the focus of the nation's largest environmental cleanup.[2] Besides the cleanup project, Hanford also hosts a commercial nuclear power plant, the Columbia Generating Station, and various centers for scientific research and development, such as the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and the LIGO Hanford Observatory.

On November 10, 2015, it was designated as part of the Manhattan Project National Historical Park alongside other sites in Oak Ridge and Los Alamos.[11]

Geography

The Hanford Site occupies 586 square miles (1,518 km2)—roughly equivalent to half of the total area of Rhode Island—within Benton County, Washington.[2] This land is closed to the general public. It is a desert environment receiving under 10 inches of annual precipitation, covered mostly by shrub-steppe vegetation. The Columbia River flows along the site for approximately 50 miles (80 km), forming its northern and eastern boundary.[12] The original site was 670 square miles (1,740 km2) and included buffer areas across the river in Grant and Franklin counties.[13] Some of this land has been returned to private use and is now covered with orchards and irrigated fields. In 2000, large portions of the site were turned over to the Hanford Reach National Monument.[14] The site is divided by function into three main areas. The nuclear reactors were located along the river in an area designated as the 100 Area; the chemical separations complexes were located inland in the Central Plateau, designated as the 200 Area; and various support facilities were located in the southeast corner of the site, designated as the 300 Area.[15]

The site is bordered on the southeast by the Tri-Cities, a metropolitan area composed of Richland, Kennewick, Pasco, and smaller communities, and home to over 230,000 residents. Hanford is a primary economic base for these cities.[16]

Climate

| Climate data for Hanford Site, Washington | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 65 (18) |

71 (22) |

87 (31) |

95 (35) |

103 (39) |

110 (43) |

115 (46) |

110 (43) |

101 (38) |

89 (32) |

73 (23) |

68 (20) |

115 (46) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 56.74 (13.74) |

60.20 (15.67) |

73.13 (22.85) |

84.80 (29.33) |

93.40 (34.11) |

102.21 (39.01) |

107.59 (41.99) |

102.93 (39.41) |

94.03 (34.46) |

80.86 (27.14) |

64.43 (18.02) |

58.70 (14.83) |

107.88 (42.16) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 38.28 (3.49) |

45.77 (7.65) |

59.43 (15.24) |

68.69 (20.38) |

77.61 (25.34) |

85.60 (29.78) |

93.98 (34.43) |

91.12 (32.84) |

79.99 (26.66) |

66.68 (19.27) |

49.68 (9.82) |

39.82 (4.34) |

66.39 (19.11) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 22.10 (−5.50) |

25.98 (−3.34) |

32.43 (0.24) |

39.00 (3.89) |

46.19 (7.88) |

53.77 (12.09) |

59.01 (15.01) |

56.71 (13.73) |

48.49 (9.16) |

39.14 (3.97) |

29.58 (−1.34) |

24.25 (−4.31) |

39.72 (4.29) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 5.13 (−14.93) |

11.24 (−11.53) |

20.53 (−6.37) |

26.19 (−3.23) |

33.50 (0.83) |

43.00 (6.11) |

48.32 (9.07) |

45.47 (7.48) |

36.50 (2.50) |

26.25 (−3.19) |

16.07 (−8.85) |

7.26 (−13.74) |

−2.88 (−19.38) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −22 (−30) |

−19 (−28) |

12 (−11) |

12 (−11) |

28 (−2) |

33 (1) |

41 (5) |

40 (4) |

25 (−4) |

17 (−8) |

0 (−18) |

−27 (−33) |

−27 (−33) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.84 (21) |

0.57 (14) |

0.28 (7.1) |

0.42 (11) |

0.52 (13) |

0.58 (15) |

0.10 (2.5) |

0.19 (4.8) |

0.34 (8.6) |

0.56 (14) |

1.05 (27) |

0.91 (23) |

6.14 (156) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 5.84 (14.8) |

3.74 (9.5) |

0.12 (0.30) |

0.00 (0.00) |

0.00 (0.00) |

0.00 (0.00) |

0.00 (0.00) |

0.00 (0.00) |

0.00 (0.00) |

0.00 (0.00) |

1.94 (4.9) |

4.44 (11.3) |

16.08 (40.8) |

| Source: [17] | |||||||||||||

Early history

The confluence of the Yakima, Snake, and Columbia rivers has been a meeting place for native peoples for centuries. The archaeological record of Native American habitation of this area stretches back over ten thousand years. Tribes and nations including the Yakama, Nez Perce, and Umatilla used the area for hunting, fishing, and gathering plant foods.[18] Hanford archaeologists have identified numerous Native American sites, including "pit house villages, open campsites, fishing sites, hunting/kill sites, game drive complexes, quarries, and spirit quest sites",[13] and two archaeological sites were listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1976.[19] Native American use of the area continued into the 20th century, even as the tribes were relocated to reservations. The Wanapum people were never forced onto a reservation, and they lived along the Columbia River in the Priest Rapids Valley until 1943.[13] Euro-Americans began to settle the region in the 1860s, initially along the Columbia River south of Priest Rapids. They established farms and orchards supported by small-scale irrigation projects and railroad transportation, with small town centers at Hanford, White Bluffs, and Richland.[20]

Manhattan Project

During World War II, the S-1 Section of the federal Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) sponsored an intensive research project on plutonium. The research contract was awarded to scientists at the University of Chicago Metallurgical Laboratory (Met Lab). At the time, plutonium was a rare element that had only recently been isolated in a University of California laboratory. The Met Lab researchers worked on producing chain-reacting "piles" of uranium to convert it to plutonium and finding ways to separate plutonium from uranium. The program was accelerated in 1942, as the United States government became concerned that scientists in Nazi Germany were developing a nuclear weapons program.[21]

Site selection

In September 1942, the Army Corps of Engineers placed the newly formed Manhattan Project under the command of General Leslie R. Groves, charging him with the construction of industrial-size plants for manufacturing plutonium and uranium.[13] Groves recruited the DuPont Company to be the prime contractor for the construction of the plutonium production complex. DuPont recommended that it be located far away from the existing uranium production facility at Oak Ridge, Tennessee. The ideal site was described by these criteria:[22]

- A large and remote tract of land

- A "hazardous manufacturing area" of at least 12 by 16 miles (19 by 26 km)

- Space for laboratory facilities at least 8 miles (13 km) from the nearest reactor or separations plant

- No towns of more than 1,000 people closer than 20 miles (32 km) from the hazardous rectangle

- No main highway, railway, or employee village closer than 10 miles (16 km) from the hazardous rectangle

- A clean and abundant water supply

- A large electric power supply

- Ground that could bear heavy loads.

In December 1942, Groves dispatched his assistant Colonel Franklin T. Matthias and DuPont engineers to scout potential sites. Matthias reported that Hanford was "ideal in virtually all respects," except for the farming towns of White Bluffs and Hanford.[23] General Groves visited the site in January and established the Hanford Engineer Works, codenamed "Site W". The federal government quickly acquired the land under its war powers authority[24] and relocated some 1,500 residents of Hanford, White Bluffs, and nearby settlements, as well as the Wanapum people, Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, and the Nez Perce Tribe.[25][26]

Construction begins

The Hanford Engineer Works (HEW) broke ground in March 1943 and immediately launched a massive and technically challenging construction project.[27] DuPont advertised for workers in newspapers for an unspecified "war construction project" in southeastern Washington, offering "attractive scale of wages" and living facilities.[28]

The construction workers (who reached a peak of 44,900 in June 1944) lived in a construction camp near the old Hanford townsite. The administrators and engineers lived in the government town established at Richland Village, which eventually had accommodation in 4,300 family units and 25 dormitories. [29] [30]

Construction of the nuclear facilities proceeded rapidly. Before the end of the war in August 1945, the HEW built 554 buildings at Hanford, including three nuclear reactors (105-B, 105-D, and 105-F) and three plutonium processing canyons (221-T, 221-B, and 221-U), each 250 meters (820 ft) long.

To receive the radioactive wastes from the chemical separations process, the HEW built "tank farms" consisting of 64 single-shell underground waste tanks (241-B, 241-C, 241-T, and 241-U).[31] The project required 386 miles (621 km) of roads, 158 miles (254 km) of railway, and four electrical substations. The HEW used 780,000 cubic yards (600,000 m3) of concrete and 40,000 short tons (36,000 t) of structural steel and consumed $230 million between 1943 and 1946.[32]

Plutonium production

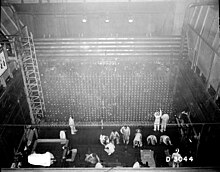

The B Reactor (105-B) at Hanford was the first large-scale plutonium production reactor in the world. It was designed and built by DuPont based on an experimental design by Enrico Fermi, and originally operated at 250 megawatts (thermal). The reactor was graphite moderated and water cooled. It consisted of a 28-by-36-foot (8.5 by 11.0 m), 1,200-short-ton (1,100 t) graphite cylinder lying on its side, penetrated through its entire length horizontally by 2,004 aluminium tubes.[33] Two hundred short tons (180 t) of uranium slugs, 1.625 inches (4.13 cm) diameter by 8 inches (20 cm) long, sealed in aluminium cans went into the tubes.[34] Cooling water was pumped through the aluminium tubes around the uranium slugs at the rate of 30,000 US gallons (110,000 L) per minute.[33]

Construction on B Reactor began in August 1943 and was completed on September 13, 1944. The reactor went critical in late September and, after overcoming nuclear poisoning, produced its first plutonium on November 6, 1944.[35] Plutonium was produced in the Hanford reactors when a uranium-238 atom in a fuel slug absorbed a neutron to form uranium-239. U-239 rapidly undergoes beta decay to form neptunium-239, which rapidly undergoes a second beta decay to form plutonium-239. The irradiated fuel slugs were transported by rail to three huge remotely operated chemical separation plants called "canyons" that were about 10 miles (16 km) away. A series of chemical processing steps separated the small amount of plutonium that was produced from the remaining uranium and the fission waste products. This first batch of plutonium was refined in the 221-T plant from December 26, 1944, to February 2, 1945, and delivered to the Los Alamos laboratory in New Mexico on February 5, 1945.[36]

Two identical reactors, D Reactor and F reactor, came online in December 1944 and February 1945, respectively. By April 1945, shipments of plutonium were headed to Los Alamos every five days, and Hanford soon provided enough material for the bombs tested at Trinity and dropped over Nagasaki.[37] Throughout this period, the Manhattan Project maintained a top secret classification. Until news arrived of the bomb dropped on Hiroshima, fewer than one percent of Hanford's workers knew they were working on a nuclear weapons project.[38] General Groves noted in his memoirs that "We made certain that each member of the project thoroughly understood his part in the total effort; that, and nothing more."[39]

Initially six reactors or "piles" were proposed, when the plutonium was to be used in the gun-type Thin Man bomb. In mid-1944 a simple gun-type bomb was found to be impractical for plutonium, and the more advanced Fat Man bomb required less plutonium. The number of piles was reduced to four and then three; and the number of chemical separation plants from four to three.[40]

Technological innovations

In the short time frame of the Manhattan Project, Hanford engineers produced many significant technological advances. As no one had ever built an industrial-scale nuclear reactor before, scientists were unsure how much heat would be generated by fission during normal operations. Seeking the greatest possible production while maintaining an adequate safety margin, DuPont engineers installed ammonia-based refrigeration systems with the D and F reactors to further chill the river water before its use as reactor coolant.[41]

Another difficulty the engineers struggled with was how to deal with radioactive contamination. Once the canyons began processing irradiated slugs, the machinery would become so radioactive that it would be unsafe for humans ever to come in contact with it. The engineers therefore had to devise methods to allow for the replacement of any component via remote control. They came up with a modular cell concept, which allowed major components to be removed and replaced by an operator sitting in a heavily shielded overhead crane. This method required early practical application of two technologies that later gained widespread use: Teflon, used as a gasket material, and closed-circuit television, used to give the crane operator a better view of the process.[42]

Cold War expansion

In September 1946, the General Electric Company assumed management of the Hanford Works under the supervision of the newly created Atomic Energy Commission. As the Cold War began, the United States faced a new strategic threat in the rise of the Soviet nuclear weapons program. In August 1947, the Hanford Works announced funding for the construction of two new weapons reactors and research leading to the development of a new chemical separations process. With this announcement, Hanford entered a new phase of expansion.[43]

By 1963, the Hanford Site was home to nine nuclear reactors along the Columbia River, five reprocessing plants on the central plateau, and more than 900 support buildings and radiological laboratories around the site.[2] Extensive modifications and upgrades were made to the original three World War II reactors, and a total of 177 underground waste tanks were built.[2] Hanford was at its peak production from 1956 to 1965. Over the entire 40 years of operations, the site produced about 63 short tons (57 t) of plutonium, supplying the majority of the 60,000 weapons in the U.S. arsenal.[2][3] Uranium-233 was also produced.[44][45][46][47]

Decommissioning

Most of the reactors were shut down between 1964 and 1971, with an average individual life span of 22 years. The last reactor, N Reactor, continued to operate as a dual-purpose reactor, being both a power reactor used to feed the civilian electrical grid via the Washington Public Power Supply System (WPPSS) and a plutonium production reactor for nuclear weapons. N Reactor operated until 1987. Since then, most of the Hanford reactors have been entombed ("cocooned") to allow the radioactive materials to decay, and the surrounding structures have been removed and buried.[48] The B-Reactor has not been cocooned and is accessible to the public on occasional guided tours. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1992,[49] and some historians advocate converting it into a museum.[50][51] B reactor was designated a National Historic Landmark by the National Park Service on August 19, 2008.[52][53]

| Reactor name | Start-up date | Shutdown date | Initial power (MWt) |

Final power (MWt) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B Reactor | Sep 1944 | Feb 1968 | 250 | 2210 |

| D Reactor | Dec 1944 | Jun 1967 | 250 | 2165 |

| F Reactor | Feb 1945 | Jun 1965 | 250 | 2040 |

| H Reactor | Oct 1949 | Apr 1965 | 400 | 2140 |

| DR ("D Replacement") Reactor | Oct 1950 | Dec 1964 | 250 | 2015 |

| C Reactor | Nov 1952 | Apr 1969 | 650 | 2500 |

| KW ("K West") Reactor | Jan 1955 | Feb 1970 | 1800 | 4400 |

| KE ("K East") Reactor | Apr 1955 | Jan 1971 | 1800 | 4400 |

| N Reactor | Dec 1963 | Jan 1987 | 4000 | 4000 |

Later operations

The United States Department of Energy assumed control of the Hanford Site in 1977. Although uranium enrichment and plutonium breeding were slowly phased out, the nuclear legacy left an indelible mark on the Tri-Cities. Since World War II, the area had developed from a small farming community to a booming "Atomic Frontier" to a powerhouse of the nuclear-industrial complex.[55] Decades of federal investment created a community of highly skilled scientists and engineers. As a result of this concentration of specialized skills, the Hanford Site was able to diversify its operations to include scientific research, test facilities, and commercial nuclear power production.

As of 2013[update], operational facilities located at the Hanford Site include:

- The Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, owned by the Department of Energy and operated by Battelle Memorial Institute

- The Fast Flux Test Facility (FFTF), a national research facility in operation from 1980 to 1992 (its last fuel was removed in 2008[56])

- LIGO's Hanford Observatory, an interferometer searching for gravitational waves[57][58][59][60]

- Columbia Generating Station, a commercial nuclear power plant operated by Energy Northwest.

- A US Navy nuclear submarine reactor dry storage site contains sealed reactor sections of 114 US Navy submarines (as of 2008[update]).[61]

The Department of Energy and its contractors offer tours of the site. Sixty public tours, each five hours long, were planned for 2009. The tours are free, require advance reservation via the department's web site, and are limited to U.S. citizens at least 18 years of age.[62]

Environmental concerns

A huge volume of water from the Columbia River was required to dissipate the heat produced by Hanford's nuclear reactors. From 1944 to 1971, pump systems drew cooling water from the river and, after treating this water for use by the reactors, returned it to the river. Before its release into the river, the used water was held in large tanks known as retention basins for up to six hours. Longer-lived isotopes were not affected by this retention, and several terabecquerels entered the river every day. The federal government kept knowledge about these radioactive releases secret.[63] Radiation was later measured 200 miles downstream as far west as the Washington and Oregon coasts.[64]

The plutonium separation process resulted in the release of radioactive isotopes into the air, which were carried by the wind throughout southeastern Washington and into parts of Idaho, Montana, Oregon, and British Columbia.[63] Downwinders were exposed to radionuclides, particularly iodine-131, with the heaviest releases during the period from 1945 to 1951. These radionuclides entered the food chain via dairy cows grazing on contaminated fields; hazardous fallout was ingested by communities who consumed radioactive food and milk. Most of these airborne releases were a part of Hanford's routine operations, while a few of the larger releases occurred in isolated incidents. In 1949, an intentional release known as the "Green Run" released 8,000 curies of iodine-131 over two days.[65] Another source of contaminated food came from Columbia River fish, an impact felt disproportionately by Native American communities who depended on the river for their customary diets.[63] A U.S. government report released in 1992 estimated that 685,000 curies of radioactive iodine-131 had been released into the river and air from the Hanford site between 1944 and 1947.[66]

Beginning in the 1960s, scientists with the U.S. Public Health Service published reports about radioactivity released from Hanford, and there were protests from the health departments of Oregon and Washington. In response to an article in the Spokane Spokesman Review in September 1985, the Department of Energy announced to declassify environmental records and, in February 1986, released 19,000 pages of previously unavailable historical documents about Hanford's operations.[63] The Washington State Department of Health collaborated with the citizen-led Hanford Health Information Network (HHIN) to publicize data about the health effects of Hanford's operations. HHIN reports concluded that residents who lived downwind from Hanford or who used the Columbia River downstream were exposed to elevated doses of radiation that placed them at increased risk for various cancers and other diseases.[63] A mass tort lawsuit brought by two thousand Hanford downwinders against the federal government has been in the court system for many years.[67] Two of six plaintiffs who went to trial in 2005 were awarded $500,000 in damages.[68]

On February 15, 2013, Governor Jay Inslee announced that a tank storing radioactive waste at the site had been leaking liquids on average of 150 to 300 gallons per year. He said that the leak posed no immediate health risk to the public, but said that should not be an excuse for not doing anything.[69] On February 22, 2013, the Governor stated that "6 more tanks at Hanford site" were "leaking radioactive waste"[70] As of 2013[update], there are 177 tanks at Hanford, 149 of which have a single shell. Historically single shell tanks were used for storing radioactive liquid waste and designed to last 20 years. By 2005, some liquid waste was transferred from single shell tanks to (safer) double shell tanks. A substantial amount of residue remains in the older single shell tanks with one containing an estimated 447,000 gallons of radioactive sludge, for example. It is believed that up to six of these "empty" tanks are leaking. Two tanks are reportedly leaking at a rate of 300 gallons (1,136 liters) per year each, while the remaining four tanks are leaking at a rate of 15 gallons (57 liters) per year each.[71][72]

Since 2003, radioactive materials are known to be leaking from Hanford into the environment. "The highest tritium concentration detected in riverbank springs during 2002 was 58,000 pCi/L (2,100 Bq/L) at the Hanford Townsite. The highest iodine-129 concentration of 0.19 pCi/L (0.007 Bq/L) was also found in a Hanford Townsite spring. The WHO guidelines for radionuclides in drinking-water limits levels of iodine-129 at 1 Bq/L, and tritium at 10,000 Bq/L.[73] Concentrations of radionuclides including tritium, technetium-99, and iodine-129 in riverbank springs near the Hanford Townsite have generally been increasing since 1994. This is an area where a major groundwater plume from the 200 East Area intercepts the river ... Detected radionuclides include strontium-90, technetium-99, iodine-129, uranium-234, −235, and −238, and tritium. Other detected contaminants include arsenic, chromium, chloride, fluoride, nitrate, and sulfate."[74]

Occupational health concerns

This section needs to be updated. (November 2016) |

Since 1987, workers have reported exposure to harmful vapors after working around underground nuclear storage tanks, with no solution found. More than 40 workers in 2014 alone reported smelling vapors and became ill with "nosebleeds, headaches, watery eyes, burning skin, contact dermatitis, increased heart rate, difficulty breathing, coughing, sore throats, expectorating, dizziness and nausea, ... Several of these workers have long-term disabilities." Doctors checked workers and cleared them to return to work. Monitors worn by tank workers have found no samples with chemicals close to the federal limit for occupational exposure.[75]

In August 2014, OSHA ordered the facility to rehire a contractor and pay $220,000 in back wages for firing them for whistleblowing on safety concerns at the site.[76]

On November 19, 2014, Washington Attorney General Bob Ferguson said the state planned to sue the DOE and its contractor to protect workers from hazardous vapors at Hanford. A 2014 report by the DOE Savannah River National Laboratory initiated by 'Washington River Protection Solutions' found that DOE's methods to study vapor releases were inadequate, particularly, that they did not account for short but intense vapor releases. They recommended "proactively sampling the air inside tanks to determine its chemical makeup; accelerating new practices to prevent worker exposures; and modifying medical evaluations to reflect how workers are exposed to vapors".[75]

Cleanup era

On June 25, 1988, the Hanford site was divided into four areas and proposed for inclusion on the National Priorities List.[77] On May 15, 1989, the Washington Department of Ecology, the United States Environmental Protection Agency, and the Department of Energy entered into the Tri-Party Agreement, which provides a legal framework for environmental remediation at Hanford.[10] As of 2014[update] the agencies are engaged in the world's largest environmental cleanup, with many challenges to be resolved in the face of overlapping technical, political, regulatory, and cultural interests. The cleanup effort is focused on three outcomes: restoring the Columbia River corridor for other uses, converting the central plateau to long-term waste treatment and storage, and preparing for the future.[78] The cleanup effort is managed by the Department of Energy under the oversight of the two regulatory agencies. A citizen-led Hanford Advisory Board provides recommendations from community stakeholders, including local and state governments, regional environmental organizations, business interests, and Native American tribes.[79] Citing the 2014 Hanford Lifecycle Scope Schedule and Cost report, the 2014 estimated cost of the remaining Hanford clean up is $113.6 billion – more than $3 billion per year for the next six years, with a lower cost projection of approximately $2 billion per year until 2046.[80][81][82] About 11,000 workers are on site to consolidate, clean up, and mitigate waste, contaminated buildings, and contaminated soil.[4] Originally scheduled to be complete within thirty years, the cleanup was less than half finished by 2008.[82] Of the four areas that were formally listed as Superfund sites on October 4, 1989, only one has been removed from the list following cleanup.[83]

While major releases of radioactive material ended with the reactor shutdown in the 1970s and many of the most dangerous wastes are contained, there are continued concerns about contaminated groundwater headed toward the Columbia River and about workers' health and safety.[82]

The most significant challenge at Hanford is stabilizing the 53,000,000 US gallons (200,000,000 L; 44,000,000 imp gal) of high-level radioactive waste stored in 177 underground tanks. By 1998, about a third of these tanks had leaked waste into the soil and groundwater.[84] As of 2008[update], most of the liquid waste has been transferred to more secure double-shelled tanks; however, 2,800,000 US gallons (11,000,000 L; 2,300,000 imp gal)of liquid waste, together with 27,000,000 US gallons (100,000,000 L; 22,000,000 imp gal) of salt cake and sludge, remains in the single-shelled tanks.[4] DOE lacks information about the extent to which the 27 double-shell tanks may be susceptible to corrosion. Without determining the extent to which the factors that contributed to the leak in AY-102 were similar to the other 27 double-shell tanks, DOE cannot be sure how long its double-shell tanks can safely store waste.[6] That waste was originally scheduled to be removed by 2018. As of 2008[update], the revised deadline was 2040.[82] Nearby aquifers contain an estimated 270,000,000,000 US gallons (1.0×1012 L; 2.2×1011 imp gal) of contaminated groundwater as a result of the leaks.[85] As of 2008[update], 1,000,000 US gallons (3,800,000 L; 830,000 imp gal) of radioactive waste is traveling through the groundwater toward the Columbia River. This waste is expected to reach the river in 12 to 50 years if cleanup does not proceed on schedule.[4] The site includes 25 million cubic feet (710,000 m3) of solid radioactive waste.[85]

Under the Tri-Party Agreement, lower-level hazardous wastes are buried in huge lined pits that will be sealed and monitored with sophisticated instruments for many years. Disposal of plutonium and other high-level wastes is a more difficult problem that continues to be a subject of intense debate. As an example, plutonium-239 has a half-life of 24,100 years, and a decay of ten half-lives is required before a sample is considered to cease its radioactivity.[86][87] In 2000, the Department of Energy awarded a $4.3 billion contract to Bechtel, a San Francisco-based construction and engineering firm, to build a vitrification plant to combine the dangerous wastes with glass to render them stable. Construction began in 2002. The plant was originally scheduled to be operational by 2011, with vitrification completed by 2028.[82][88][89] As of 2012[update], according to a study by the General Accounting Office, there were a number of serious unresolved technical and managerial problems.[90] As of 2013[update] estimated costs were $13.4 billion with commencement of operations estimated to be in 2022 and about 3 decades of operation.[91]

In May 2007, state and federal officials began closed-door negotiations about the possibility of extending legal cleanup deadlines for waste vitrification in exchange for shifting the focus of the cleanup to urgent priorities, such as groundwater remediation. Those talks stalled in October 2007. In early 2008, a $600 million cut to the Hanford cleanup budget was proposed. Washington state officials expressed concern about the budget cuts, as well as missed deadlines and recent safety lapses at the site, and threatened to file a lawsuit alleging that the Department of Energy is in violation of environmental laws.[82] They appeared to step back from that threat in April 2008 after another meeting of federal and state officials resulted in progress toward a tentative agreement.[92]

During excavations from 2004 to 2007 a sample of purified plutonium was uncovered inside a safe in a waste trench, and has been dated to about the 1940s, making it the second-oldest sample of purified plutonium known to exist. Analyses published in 2009 concluded that the sample originated at Oak Ridge, and was one of several sent to Hanford for optimization tests of the T-Plant until Hanford could produce its own plutonium. Documents refer to such a sample, belonging to "Watt's group", which was disposed of in its safe when a radiation leak was suspected.[93][94]

Some of the radioactive waste at Hanford was supposed to be stored in the planned Yucca Mountain nuclear waste repository, but after that project was cancelled due to the opposition of citizens of Nevada, Washington State sued. They were joined by South Carolina. Their first suit was dismissed, and second suits have been filed.

A potential radioactive leak was reported in 2013; the clean up was estimated to have cost $40 billion with $115 billion more required.[95]

Hanford organizations

The Hanford site operations were initially directed by Colonel Franklin Matthias of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Postwar the Atomic Energy Commission took over, and then the Energy Research and Development Administration. Hanford operations are currently directed by the U.S. Department of Energy. It has been operated under government contract by various private companies over the years – the table which follows summarizes the operating contractors through 2000.[96]

| Year begun | Month | Organization | Responsibility | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1942 | December 12 | U.S. Army Corps of Engineers | Lead U.S. Government entity | Held role until January 1, 1947 |

| 1942 | December 12 | E.I. DuPont de Nemours & Company (DuPont) | All site activities | Initial Hanford site contractor |

| 1946 | September 1 | General Electric Company (GE) | All site activities | Replaced DuPont |

| 1947 | January 1 | Atomic Energy Commission | Lead U.S. Government entity | Replaced U.S. Army Corps of Engineers |

| 1953 | May 15 | Vitro Engineers | Hanford Engineering Services | Assumed GEs new facility design role |

| 1953 | June 1 | J.A. Jones Construction | Hanford Construction Services | Assumed GEs construction role |

| 1965 | January 1 | U.S. Testing | Environmental & bioassay testing | Assumed GEs environmental and bioassay testing role |

| 1965 | January 4 | Battelle Memorial Institute | Pacific Northwest Laboratory (PNL) | Assumed GE's laboratory operations – subsequently renamed Pacific Northwest National Laboratory |

| 1965 | July 1 | Computer Sciences Corporation (CSC) | Computer services | New scope |

| 1965 | August 1 | Hanford Occupational Health Foundation | Industrial Medicine | Assumed GE's industrial medicine role |

| 1965 | September 10 | Douglas United Nuclear | Single pass reactor operations & fuel fabrication | Assumed part of GE's reactor operations |

| 1966 | January 1 | Isochem | Chemical processing | Assumed GE's chemical processing operations |

| 1966 | March 1 | ITT Federal Support Services, Inc. | Support services | Assumed |

| 1967 | July 1 | Douglas United Nuclear | N Reactor operation | Assumed remainder of GE's reactor operations |

| 1967 | September 4 | Atlantic Richfield Hanford Company | Chemical Processing | Replaced Isochem |

| 1967 | August 8 | Hanford Environmental Health Foundation | Industrial Medicine | Name change only |

| 1970 | February 1 | Westinghouse Hanford Company | Hanford Engineering Development Laboratory | Spun off from PNL with mission to build the Fast Flux Test Facility |

| 1971 | September | ARHCO | Support Services | Replaces ITT/PSS |

| 1973 | April | United Nuclear Industries, Inc. | All production reactor operations | Name change from Douglas United Nuclear only |

| 1975 | January 1 | Energy Research and Development Administration (ERDA) | Lead U.S. Government entity | Replaced AEC – managed site until October 1, 1977 |

| 1975 | October 1 | Boeing Computer Services (BCS) | Computer services | Replaced CSC |

| 1977 | October 1 | U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) | Lead U.S. Government Agency | Replaced ERDA – manages site presently |

| 1977 | October 1 | Rockwell Hanford Operations (RHO) | Chemical Processing & Support Services | Replaces ARCHO |

| 1981 | June | Braun Hanford Company (BHC) | Architect & Engineering Services | Replaces Vitro |

| 1982 | March | Kaiser Engineering Hanford (KEH) | Architect & Engineering Services | Replaces BHC |

| 1987 | March 1 | KEH | Construction | Consolidated contract includes former J.A. Jones work |

| 1987 | June 29 | WHC | Site management & operations | Consolidated contract includes former RHO, UNC & KEH work. |

| 1996 | October 1 | Fluor Daniel Hanford, Inc. (FDH) | Site management & operations | FDH is integrating contractor with 13 subcontracted companies |

| 2000 | February 7 | Fluor Hanford | Site cleanup operations | Transition to site cleanup (13 Fluor subcontractors held various roles) |

| 2000 | December 11 | Bechtel National, Inc. | Engineering, construction, and commissioning of the Waste Treatment Plant | |

| 2008 | October 1 | Ch2M Hill Plateau Remediation Company | Central plateau cleanup and closure | |

| 2009 | April 8 | Washington Closure Hanford | River corridor cleanup and closure | |

| 2009 | May 26 | Mission Support Alliance | Site infrastructure and services | Consolidated services contract |

| 2009 | October 1 | Washington River Protection Solutions | Tank Farm operations |

Other divisions of the site (historical)

- Plutonium Finishing Plant (PFP) – made plutonium metal for use in weapons[97]

- B Plant, S Plant, T Plant – processing, separation, and extraction of various chemicals and isotopes[98][99]

- Health Instruments Section – an attempt to keep workers and the environment safe[99]

- REDOX Plant / C Plant – recovered wasted uranium from World War II processes[99]

- Experimental Animal Farm and Aquatic Biology Laboratory[99]

- Technical Center – radiochemistry, physics, metallurgy, biophysics, radioactive sewer, neutralization, metal fab, fuels manufacturing[99]

- Tank Farms – storage of liquid nuclear waste[99]

- Metal Recovery Plant / U Plant – recover uranium from tank farms[99]

- Uranium Trioxide Plant (aka Uranium Oxide Plant aka UO3 Plant) – took output from other plants (i.e. liquid uranyl nitrate hexahydrate from U plant and PUREX plant), made uranium trioxide powder[98][99][100][101][102][103][104]

- Plutonium-Uranium Extraction Plant / PUREX Plant – extracted useful material from spent fuel waste (also see the PUREX article)[98][99]

- Plutonium Recycle Test Reactor (PRTR) – experimented with alternative fuel mixtures[97][99][105][106]

- Plutonium Fuels Pilot Plant (PFPP) – see PRTR

Historic photos

-

Cooling water retention basins at the F-Reactor

-

Underground tank farm with 12 of the site's 177 waste storage tanks

-

Inside one of the waste storage tanks

-

Inside the PUREX facility

-

View of the central plateau from Rattlesnake Mountain

-

The government town of Richland in the early days of the site

-

Hanford workers lining up for paychecks

-

Hanford scientists feeding radioactive food to sheep

-

Testing a sheep's thyroid for radiation

-

Cold War-era billboard

-

"Atomic Frontier Days" parade in Richland

See also

- Black Ops 2 (Green Run location)

- Fernald Feed Materials Production Center

- Harry Shearer's Le Show— a weekly radio show and podcast featuring "Clean, Safe, Too Cheap to Meter", a series of regular updates on the Hanford Site, and nuclear power news around the world.

- Idaho National Laboratory

- James Acord

- Lists of nuclear disasters and radioactive incidents

- Los Alamos National Laboratory

- Oak Ridge National Laboratory

- Paducah Gaseous Diffusion Plant

- Pantex Plant

- Plutopia

- Radioactive contamination from the Rocky Flats Plant

- Rocky Flats Plant

- Safe As Mother's Milk

- Sandia National Laboratories

- Savannah River Site

- Timeline of nuclear weapons development

References

- ^ "B Reactor". United States Department of Energy. Archived from the original on February 2, 2010. Retrieved January 29, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f "Hanford Site: Hanford Overview". United States Department of Energy. Archived from the original on June 5, 2012. Retrieved February 13, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Science Watch: Growing Nuclear Arsenal". The New York Times. April 28, 1987. Retrieved January 29, 2007.

- ^ a b c d "Hanford Quick Facts". Washington Department of Ecology. Archived from the original on June 24, 2008. Retrieved January 19, 2010.

- ^ "Hanford Facts". psr.org. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ^ a b GAO (November 25, 2014). "Condition of Tanks May Further Limit DOE's Ability to Respond to Leaks and Intrusions- Highlights". U.S. GAO. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

- ^ Stang, John (December 21, 2010). "Spike in radioactivity a setback for Hanford cleanup". Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

- ^ Harden, Blaine; Dan Morgan (June 2, 2007). "Debate Intensifies on Nuclear Waste". Washington Post. p. A02. Retrieved January 29, 2007.

- ^ Dininny, Shannon (April 3, 2007). "U.S. to Assess the Harm from Hanford". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Associated Press. Retrieved January 29, 2007.

- ^ a b Schneider, Keith (February 28, 1989). "Agreement for a Cleanup at Nuclear Site". The New York Times. Retrieved January 30, 2008.

- ^ Richard, Terry (November 10, 2015). "Washington's Hanford becomes part of national historical park". The Oregonian. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- ^ "The Columbia River at Risk: Why Hanford Cleanup is Vital to Oregon". oregon.gov. August 1, 2007. Archived from the original on June 2, 2010. Retrieved March 31, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Hanford Cultural Resources Program, U.S. Department of Energy (2002). Hanford Site Historic District: History of the Plutonium Production Facilities, 1943–1990. Columbus, OH: Battelle Press. p. 1.12. ISBN 1-57477-133-7.

- ^ Seelye, Katharine (June 10, 2000). "Gore Praises Move to Aid Salmon Run". The New York Times. Retrieved January 29, 2007.

- ^ "Site Map Area and Description". Columbia Riverkeepers. Archived from the original on February 8, 2007. Retrieved January 29, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Lewis, Mike (April 19, 2002). "In strange twist, Hanford cleanup creates latest boom". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved January 29, 2007.

- ^ "HANFORD A E C, WASHINGTON (453444)". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved April 27, 2016.

- ^ "Hanford Reach National Monument". HistoryLink.org: The Online Encyclopedia of Washington State History. Retrieved January 29, 2007.

- ^ Hanford Island Archaeological Site (NRHP #76001870) and Hanford North Archaeological District (NHRP #76001871). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007. (See also the commercial site National Register of Historic Places.)

- ^ Gerber, Michele (2002). On the Home Front: The Cold War Legacy of the Hanford Nuclear Site (2nd ed.). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 16–22. ISBN 0-8032-7101-8.

- ^ Hanford Cultural Resources Program, U.S. Department of Energy (2002). Hanford Site Historic District: History of the Plutonium Production Facilities, 1943–1990. Columbus, OH: Battelle Press. p. 1.10. ISBN 1-57477-133-7.

- ^ Gerber, Michele (1992). Legend and Legacy: Fifty Years of Defense Production at the Hanford Site. Richland, Washington: Westinghouse Hanford Company. p. 6.

- ^ Franklin, Matthias (January 14, 1987). Hanford Engineer Works, Manhattan Engineer District: Early History. Speech to the Technical Exchange Program.

- ^ Second War Powers Act 56 Stat. 176 (1942)

- ^ Department of Energy: Hanford. "Department of Energy's Tribal Program: The DOE Tribal Program at Hanford". DOE Hanford.gov. Retrieved April 20, 2014.

- ^ Brown, Kate (2013). Plutopia : nuclear families, atomic cities, and the great Soviet and American plutonium disasters. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 33–36. ISBN 978-0-19-985576-6.

- ^ Oldham, Kit (March 5, 2003). "Construction of massive plutonium production complex at Hanford begins in March 1943". History Link. Retrieved April 6, 2008.

- ^ "Needed by E. I. duPont de Nemours & Company for Pacific Northwest (advertisement)". Milwaukee Sentinel. June 6, 1944. pp. 1–5. Retrieved March 25, 2013.

- ^ Nichols, K. D. The Road to Trinity page 138 (1987, Morrow, New York) ISBN 0-688-06910-X

- ^ Thayer, H. (1996). Management of the Hanford Engineer Works in World War II. New York, NY: American Society of Civil Engineers Press.

- ^ Hanford Cultural Resources Program, U.S. Department of Energy (2002). Hanford Site Historic District: History of the Plutonium Production Facilities, 1943–1990. Columbus, OH: Battelle Press. p. 1.21–1.23. ISBN 1-57477-133-7.

- ^ Gerber, Michele (2002). On the Home Front: The Cold War Legacy of the Hanford Nuclear Site (2nd ed.). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 35–36. ISBN 0-8032-7101-8.

- ^ a b Hanford Cultural Resources Program, U.S. Department of Energy (2002). Hanford Site Historic District: History of the Plutonium Production Facilities, 1943–1990. Columbus, OH: Battelle Press. p. 1.15, 1.30. ISBN 1-57477-133-7.

- ^ Harvey, David; O'Conner, Georganne. "History of the Hanford Site 1943–1990" (PDF). Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. p. 11. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- ^ Hanford Cultural Resources Program, U.S. Department of Energy (2002). Hanford Site Historic District: History of the Plutonium Production Facilities, 1943–1990. Columbus, OH: Battelle Press. p. 1.22–1.27. ISBN 1-57477-133-7.

- ^ Findlay, John; Bruce Hevly (1995). Nuclear Technologies and Nuclear Communities: A History of Hanford and the Tri-Cities, 1943–1993. Seattle, WA: Hanford History Project, Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest, University of Washington. p. 50.

- ^ Hanford Cultural Resources Program, U.S. Department of Energy (2002). Hanford Site Historic District: History of the Plutonium Production Facilities, 1943–1990. Columbus, OH: Battelle Press. p. 1.27. ISBN 1-57477-133-7.

- ^ Hanford Cultural Resources Program, U.S. Department of Energy (2002). Hanford Site Historic District: History of the Plutonium Production Facilities, 1943–1990. Columbus, OH: Battelle Press. p. 1.22. ISBN 1-57477-133-7.

- ^ Groves, Leslie (1983). Now It Can Be Told: The Story of the Manhattan Project. New York, NY: Da Capo Press. p. xv.

- ^ Nichols, Kenneth (1987). The Road to Trinity. New York: William Morrow. ISBN 0-688-06910-X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) p136 - ^ Sanger, S. L. Working on the Bomb: an Oral History of WWII Hanford. Portland, Oregon: Continuing Education Press, Portland State University. p. 70.

- ^ Sanger, S. L. Working on the Bomb: an Oral History of WWII Hanford. Portland, Oregon: Continuing Education Press, Portland State University. interview with Generaux.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help) - ^ Hanford Cultural Resources Program, U.S. Department of Energy (2002). Hanford Site Historic District: History of the Plutonium Production Facilities, 1943–1990. Columbus, OH: Battelle Press. p. 1.42–45. ISBN 1-57477-133-7.

- ^ "Historical use of thorium at Hanford" (PDF). hanfordchallenge.org. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ^ "Chronology of Important FOIA Documents: Hanford's Semi-Secret Thorium to U-233 Production Campaign" (PDF). hanfordchallenge.org. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ^ "Questions and Answers on Uranium-233 at Hanford" (PDF). radioactivist.org. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ^ "Hanford Radioactivity in Salmon Spawning Grounds" (PDF). clarku.edu. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ^ "Cocooning Hanford Reactors". City of Richland. December 2, 2003. Archived from the original on June 11, 2008. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ NRHP site #92000245. "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007. (See also the commercial site National Register of Historic Places.)

- ^ "B-Reactor Museum Association". B Reactor Museum Association. January 2008. Retrieved January 29, 2007.

- ^ "Big Step Toward B Reactor Preservation". KNDO/KNDU News. March 12, 2008. Retrieved April 6, 2008.

- ^ Chemical & Engineering News Vol. 86 No. 35, September 1, 2008, "Hanford's B Reactor gets LANDMARK Status", p. 37

- ^ "National Historic Landmarks Program – B Reactor". National Park Service. August 19, 2007. Retrieved January 5, 2009.

- ^ "Plutonium: the first 50 years: United States plutonium production, acquisition, and utilization from 1944 through 1994". U.S. Department of Energy. Retrieved January 29, 2007.

- ^ Hevly, Bruce; John Findlay (1998). The Atomic West. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

- ^ Cary, Annette (June 3, 2009). "Fast Flux Test Facility shutdown completed at Hanford". Hanford News. Archived from the original on November 17, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Twilley, Nicola. "Gravitational Waves Exist: The Inside Story of How Scientists Finally Found Them". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved February 12, 2016.

- ^ Abbott, B.P.; et al. (2016). "Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Black Hole Merger". Phys. Rev. Lett. 116: 061102. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.061102.

- ^ Naeye, Robert (February 11, 2016). "Gravitational Wave Detection Heralds New Era of Science". Sky and Telescope. Retrieved February 12, 2016.

- ^ Castelvecchi, Davide; Witze, Alexandra (February 11, 2016). "Einstein's gravitational waves found at last". Nature News. doi:10.1038/nature.2016.19361. Retrieved February 11, 2016.

- ^ "Submarine". navy.memorieshop.com. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ^ "Hanford Site Tours". United States Department of Energy. Archived from the original on April 2, 2012. Retrieved April 1, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e "An Overview of Hanford and Radiation Health Effects". Hanford Health Information Network. Archived from the original on January 6, 2010. Retrieved January 29, 2007.

- ^ "Radiation Flowed 200 Miles to Sea, Study Finds". The New York Times. July 17, 1992. Retrieved January 29, 2007.

- ^ Gerber, Michele (2002). On the Home Front: The Cold War Legacy of the Hanford Nuclear Site (2nd ed.). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 78–80. ISBN 0-8032-7101-8.

- ^ Martin, Hugo (August 13, 2008). "Nuclear site now a tourist hot spot". The Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Hanford Downwinders Litigation Website. Downwinders.com. Retrieved on September 27, 2009.

- ^ McClure, Robert (May 21, 2005). "Downwinders' court win seen as 'great victory'". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved January 29, 2007.

- ^ "Tank storing radioactive waste leaking in Washington". CNN. February 16, 2013. Retrieved February 15, 2013.

- ^ "Washington Gov. Inslee's office: 6 more tanks at Hanford site are leaking radioactive waste". Breaking News. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- ^ "Gov: 6 underground Hanford nuclear tanks leaking | Inquirer News". Newsinfo.inquirer.net. March 23, 2004. Retrieved February 23, 2013.

- ^ Johnson, Eric (February 1, 2013). "Radioactive waste leaking from six tanks at Washington state nuclear site". Reuters. Retrieved February 23, 2013.

- ^ "Radiological Aspects (water sanitation)" (PDF). www.who.int. WHO.

- ^ "Hanford Site National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) Characterization" (PDF). PNNL-6415 Rev. 17. Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. September 2005.

- ^ a b Nicholas K. Geranios (November 19, 2014). "Washington to sue over nuclear site's tank vapors". Katu.com. Associated Press. Retrieved December 19, 2014.

- ^ "OSHA orders Hanford nuclear facility contractor to reinstate worker fired for raising environmental safety concerns". OSHA. August 20, 2014.

- ^ "Hanford – Washington Superfund site". U.S. EPA. Retrieved February 3, 2010.

- ^ "Hanford Site Tour Script" (PDF). United States Department of Energy. October 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 27, 2008. Retrieved January 29, 2007.

- ^ "Hanford Site: Hanford Advisory Board". United States Department of Energy. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- ^ Tri-Party Agreement: Department of Energy, Washington State Department of Ecology and the U.S. Environmental Protection Aency. "2014 Hanford Lifecycle Scope, Schedule and Cost Report" (PDF). February, 2014. DOE, WSDE, EPA. Retrieved April 20, 2014.

- ^ Cary, Annette (February 21, 2014). "New Hanford clean up price tag is $113.6B". Yakima Herald. Retrieved April 20, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Stiffler, Lisa (March 20, 2008). "Troubled Hanford cleanup has state mulling lawsuit". Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

- ^ "Hanford 1100-Area (USDOE) Superfund site". U.S. EPA. Retrieved February 3, 2010.

- ^ Wald, Matthew (January 16, 1998). "Panel Details Management Flaws at Hanford Nuclear Waste Site". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 11, 2008. Retrieved January 29, 2007.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Wolman, David (April 2007). "Fission Trip". Wired Magazine. p. 78.

- ^ Hanson, Laura A. (November 2000). "Radioactive Waste Contamination of Soil and Groundwater at the Hanford Site" (PDF). University of Idaho. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Gephart, Roy (2003). Hanford: A Conversation About Nuclear Waste and Cleanup. Columbus, OH: Battelle Press. ISBN 1-57477-134-5.

- ^ Dininny, Shannon (September 8, 2006). "Hanford plant now $12.2 billion". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved January 29, 2007.

- ^ The Economist, "Nuclear waste: From bombs to $800 handbags", March 19, 2011, p. 40.

- ^ "Hanford Waste Treatment Plant: DOE Needs to Take Action to Resolve Technical and Management Challenges". GAO-13-38. General Accounting Office. December 19, 2012. Retrieved May 9, 2013.

- ^ Valerie Brown (May 9, 2013). "Hanford Nuclear Waste Cleanup Plant May Be Too Dangerous: Safety issues make plans to clean up a mess left over from the construction of the U.S. nuclear arsenal uncertain". Scientific American. Retrieved May 9, 2013.

The Vit Plant was supposed to start operating in 2007 and is now projected to begin in 2022. Its original budget was $4.3 billion and is now estimated at $13.4 billion.

- ^ Stiffler, Lisa (April 3, 2008). "State steps back from brink of Hanford suit". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved May 8, 2008.

- ^ Chemical & Engineering News: Antique Plutonium: Manhattan Project-era plutonium is found in a glass jug during Hanford Site cleanup(subscription required)

- ^ Annette Cary (January 25, 2009). "Historic plutonium found in safe at Hanford". TRI-CITY HERALD. Seattle Pi.

- ^ "Possible radioactive leak into soil at Hanford". CBS News. June 21, 2013.

- ^ Briggs, J.D. (March 22, 2001). "Historical Time Line and Information about the Hanford Site, Richland, Washington" (PDF). Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- ^ a b Lini, D.C.; L. H. Rodgers / SAIC / FH (March 2002). "Plutonium Finishing Plant Plutonium- Uranium Oxide" (PDF). US DOE. Retrieved October 1, 2009.

- ^ a b c "222-S Hanford Site". Advanced Technologies and Laboratories Intl. Retrieved October 1, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Gerber, M.S. (February 2001). "History of Hanford Site Defense Production (Brief)" (PDF). Fluor Hanford / US DOE. Retrieved October 1, 2009.

- ^ Freer, Brian; Charles Conway (June 2002). "History of the Plutonium Production Facilities at the Hanford Site Historic District, 1943–1990. Section 4 – Chemical Separations" (PDF). US DOE. doi:10.2172/807939.

- ^ Brevick, Stroup, Funk; et al. (1997). "Supporting Document for the Historical Tank Content Estimate for SY-Tank Farm". US DOE. Retrieved October 5, 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Johnson; et al. (1994). "Historical records of radioactive contamination in biota at the 200 Areas of the Hanford Site". US DOE. Retrieved October 5, 2009.

- ^ Carbaugh E.H., Bihl, D.E., and MacLellan, J.A. (January 1, 2003). "Methods and Models of the Hanford Internal Dosimetry Program, PNNL-MA-860" (PDF). Retrieved October 5, 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Executive Summary Hanford Recycled Uranium Project" (PDF). US DOE. June 2000. doi:10.2172/803918. Retrieved October 5, 2009.

- ^ Nuclear Engineering International (January 23, 2014). "Hanford removes plutonium test reactor". neimagazine.com. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ^ - Department of Energy (January 22, 2014). "Massive Hanford Test Reactor Removed – Plutonium Recycle Test Reactor removed from Hanford's 300 Area". energy.gov. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

Further reading

- John M. Findlay and Bruce Hevly. Atomic Frontier Days: Hanford and the American West (University of Washington Press; 2011) 368 pages; explores the history of the Hanford nuclear reservation and the tri-cities of Richland, Pasco, and Kennewick, Washington

External links

- Official Hanford website Department of Energy.

- Washington Department of Ecology – Nuclear Waste Program State agency that regulates Hanford cleanup.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Federal agency that regulates Hanford cleanup.

- Hanford Challenge Hanford watchdog group, based in Seattle.

- Hanford News Current news from the Tri-City Herald.

- Hanford Site Environmental Report Detailed annual report on radioactive concentrations measured at the Hanford Site.

- Atomic Heritage Foundation Historic Preservation of Manhattan Project Sites at Hanford.

- "Ranger in Your Pocket" Online tours of Hanford's Manhattan Project sites Atomic Heritage Foundation

- B Reactor Museum Association A collection of Hanford-related documents from a group fighting to preserve the B-100 Reactor at Hanford.

- Contaminated US site faces 'catastrophic' nuclear leak 2008 New Scientist report.

- Heart of America Northwest Hanford watchdog group, based in Seattle.

- The Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues Annotated bibliography for the Hanford Site.

- A Review of Data Triples Plutonium Waste Figures Matthew L. Wald, The New York Times, July 10, 2010

- Washington River Protection Solutions Hanford environmental remediation contractor.

- Safe as Mother's Milk: The Hanford Project

- Hanford Documentary produced by Oregon Public Broadcasting

- Hanford Site

- Geography of Benton County, Washington

- Columbia River

- Environmental disasters in the United States

- Geography of Washington (state)

- History of Washington (state)

- Manhattan Project

- Buildings and structures in Washington (state)

- Nuclear history of the United States

- Nuclear weapons infrastructure of the United States

- Radioactive waste repositories

- Tri-Cities, Washington

- United States Department of Energy facilities

- Closed military facilities of the United States in the United States

- Buildings and structures in Benton County, Washington

- Visitor attractions in Benton County, Washington

- Radioactively contaminated areas

- 1943 establishments in Washington (state)

- Military Superfund sites

- Superfund sites in Washington (state)

- Nuclear accidents and incidents

- Military research of the United States

- Gravitational-wave astronomy

- Atomic tourism