Henri Poincaré

Jules Henri Poincaré (French: [ʒyl ɑ̃ʁi pwɛ̃kaʁe];[2][3] 29 April 1854 – 17 July 1912) was a French mathematician, theoretical physicist, engineer, and a philosopher of science. He is often described as a polymath, and in mathematics as The Last Universalist by Eric Temple Bell,[4] since he excelled in all fields of the discipline as it existed during his lifetime.

As a mathematician and physicist, he made many original fundamental contributions to pure and applied mathematics, mathematical physics, and celestial mechanics.[5] He was responsible for formulating the Poincaré conjecture, which was one of the most famous unsolved problems in mathematics until it was solved in 2002–2003. In his research on the three-body problem, Poincaré became the first person to discover a chaotic deterministic system which laid the foundations of modern chaos theory. He is also considered to be one of the founders of the field of topology.

Poincaré made clear the importance of paying attention to the invariance of laws of physics under different transformations, and was the first to present the Lorentz transformations in their modern symmetrical form. Poincaré discovered the remaining relativistic velocity transformations and recorded them in a letter to Dutch physicist Hendrik Lorentz (1853–1928) in 1905. Thus he obtained perfect invariance of all of Maxwell's equations, an important step in the formulation of the theory of special relativity.

The Poincaré group used in physics and mathematics was named after him.

Life

Poincaré was born on 29 April 1854 in Cité Ducale neighborhood, Nancy, Meurthe-et-Moselle into an influential family.[6] His father Leon Poincaré (1828–1892) was a professor of medicine at the University of Nancy.[7] His adored younger sister Aline married the spiritual philosopher Emile Boutroux. Another notable member of Henri's family was his cousin, Raymond Poincaré, who would serve as President of France from 1913 to 1920, and who was a fellow member of the Académie française.[8] He was raised in the Roman Catholic faith.

Education

During his childhood he was seriously ill for a time with diphtheria and received special instruction from his mother, Eugénie Launois (1830–1897).

In 1862, Henri entered the Lycée in Nancy (now renamed the Lycée Henri Poincaré in his honour, along with the University of Nancy). He spent eleven years at the Lycée and during this time he proved to be one of the top students in every topic he studied. He excelled in written composition. His mathematics teacher described him as a "monster of mathematics" and he won first prizes in the concours général, a competition between the top pupils from all the Lycées across France. His poorest subjects were music and physical education, where he was described as "average at best".[9] However, poor eyesight and a tendency towards absentmindedness may explain these difficulties.[10] He graduated from the Lycée in 1871 with a bachelor's degree in letters and sciences.

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, he served alongside his father in the Ambulance Corps.

Poincaré entered the École Polytechnique in 1873 and graduated in 1875. There he studied mathematics as a student of Charles Hermite, continuing to excel and publishing his first paper (Démonstration nouvelle des propriétés de l'indicatrice d'une surface) in 1874. From November 1875 to June 1878 he studied at the École des Mines, while continuing the study of mathematics in addition to the mining engineering syllabus, and received the degree of ordinary mining engineer in March 1879.[11]

As a graduate of the École des Mines, he joined the Corps des Mines as an inspector for the Vesoul region in northeast France. He was on the scene of a mining disaster at Magny in August 1879 in which 18 miners died. He carried out the official investigation into the accident in a characteristically thorough and humane way.

At the same time, Poincaré was preparing for his doctorate in sciences in mathematics under the supervision of Charles Hermite. His doctoral thesis was in the field of differential equations. It was named Sur les propriétés des fonctions définies par les équations différences. Poincaré devised a new way of studying the properties of these equations. He not only faced the question of determining the integral of such equations, but also was the first person to study their general geometric properties. He realised that they could be used to model the behaviour of multiple bodies in free motion within the solar system. Poincaré graduated from the University of Paris in 1879.

The first scientific achievements

After receiving his degree, Poincaré began teaching as junior lecturer in mathematics at the University of Caen in Normandy (in December 1879). At the same time he published his first major article concerning the treatment of a class of automorphic functions.

There, in Caen, he met his future wife, Louise Poulin d'Andesi (Louise Poulain d'Andecy) and on 20 April 1881, they married. Together they had four children: Jeanne (born 1887), Yvonne (born 1889), Henriette (born 1891), and Léon (born 1893).

Poincaré immediately established himself among the greatest mathematicians of Europe, attracting the attention of many prominent mathematicians. In 1881 Poincaré was invited to take a teaching position at the Faculty of Sciences of the University of Paris; he accepted the invitation. During the years of 1883 to 1897, he taught mathematical analysis in École Polytechnique.

In 1881–1882, Poincaré created a new branch of mathematics: the qualitative theory of differential equations. He showed how it is possible to derive the most important information about the behavior of a family of solutions without having to solve the equation (since this may not always be possible). He successfully used this approach to problems in celestial mechanics and mathematical physics.

Career

He never fully abandoned his mining career to mathematics. He worked at the Ministry of Public Services as an engineer in charge of northern railway development from 1881 to 1885. He eventually became chief engineer of the Corps de Mines in 1893 and inspector general in 1910.

Beginning in 1881 and for the rest of his career, he taught at the University of Paris (the Sorbonne). He was initially appointed as the maître de conférences d'analyse (associate professor of analysis).[12] Eventually, he held the chairs of Physical and Experimental Mechanics, Mathematical Physics and Theory of Probability, and Celestial Mechanics and Astronomy.

In 1887, at the young age of 32, Poincaré was elected to the French Academy of Sciences. He became its president in 1906, and was elected to the Académie française in 1909.

In 1887, he won Oscar II, King of Sweden's mathematical competition for a resolution of the three-body problem concerning the free motion of multiple orbiting bodies. (See #The three-body problem section below)

In 1893, Poincaré joined the French Bureau des Longitudes, which engaged him in the synchronisation of time around the world. In 1897 Poincaré backed an unsuccessful proposal for the decimalisation of circular measure, and hence time and longitude.[13] It was this post which led him to consider the question of establishing international time zones and the synchronisation of time between bodies in relative motion. (See #Work on relativity section below)

In 1899, and again more successfully in 1904, he intervened in the trials of Alfred Dreyfus. He attacked the spurious scientific claims of some of the evidence brought against Dreyfus, who was a Jewish officer in the French army charged with treason by colleagues.

In 1912, Poincaré underwent surgery for a prostate problem and subsequently died from an embolism on 17 July 1912, in Paris. He was 58 years of age. He is buried in the Poincaré family vault in the Cemetery of Montparnasse, Paris.

A former French Minister of Education, Claude Allègre, has recently (2004) proposed that Poincaré be reburied in the Panthéon in Paris, which is reserved for French citizens only of the highest honour.[14]

Students

Poincaré had two notable doctoral students at the University of Paris, Louis Bachelier (1900) and Dimitrie Pompeiu (1905).[15]

Work

Summary

Poincaré made many contributions to different fields of pure and applied mathematics such as: celestial mechanics, fluid mechanics, optics, electricity, telegraphy, capillarity, elasticity, thermodynamics, potential theory, quantum theory, theory of relativity and physical cosmology.

He was also a populariser of mathematics and physics and wrote several books for the lay public.

Among the specific topics he contributed to are the following:

- algebraic topology

- the theory of analytic functions of several complex variables

- the theory of abelian functions

- algebraic geometry

- Poincaré was responsible for formulating one of the most famous problems in mathematics, the Poincaré conjecture, proven in 2003 by Grigori Perelman.

- Poincaré recurrence theorem

- hyperbolic geometry

- number theory

- the three-body problem

- the theory of diophantine equations

- the theory of electromagnetism

- the special theory of relativity

- In an 1894 paper, he introduced the concept of the fundamental group.

- In the field of differential equations Poincaré has given many results that are critical for the qualitative theory of differential equations, for example the Poincaré sphere and the Poincaré map.

- Poincaré on "everybody's belief" in the Normal Law of Errors (see normal distribution for an account of that "law")

- Published an influential paper providing a novel mathematical argument in support of quantum mechanics.[16][17]

The three-body problem

The problem of finding the general solution to the motion of more than two orbiting bodies in the solar system had eluded mathematicians since Newton's time. This was known originally as the three-body problem and later the n-body problem, where n is any number of more than two orbiting bodies. The n-body solution was considered very important and challenging at the close of the 19th century. Indeed, in 1887, in honour of his 60th birthday, Oscar II, King of Sweden, advised by Gösta Mittag-Leffler, established a prize for anyone who could find the solution to the problem. The announcement was quite specific:

Given a system of arbitrarily many mass points that attract each according to Newton's law, under the assumption that no two points ever collide, try to find a representation of the coordinates of each point as a series in a variable that is some known function of time and for all of whose values the series converges uniformly.

In case the problem could not be solved, any other important contribution to classical mechanics would then be considered to be prizeworthy. The prize was finally awarded to Poincaré, even though he did not solve the original problem. One of the judges, the distinguished Karl Weierstrass, said, "This work cannot indeed be considered as furnishing the complete solution of the question proposed, but that it is nevertheless of such importance that its publication will inaugurate a new era in the history of celestial mechanics." (The first version of his contribution even contained a serious error; for details see the article by Diacu[18]). The version finally printed contained many important ideas which led to the theory of chaos. The problem as stated originally was finally solved by Karl F. Sundman for n = 3 in 1912 and was generalised to the case of n > 3 bodies by Qiudong Wang in the 1990s.

Work on relativity

Local time

Poincaré's work at the Bureau des Longitudes on establishing international time zones led him to consider how clocks at rest on the Earth, which would be moving at different speeds relative to absolute space (or the "luminiferous aether"), could be synchronised. At the same time Dutch theorist Hendrik Lorentz was developing Maxwell's theory into a theory of the motion of charged particles ("electrons" or "ions"), and their interaction with radiation. In 1895 Lorentz had introduced an auxiliary quantity (without physical interpretation) called "local time" [19] and introduced the hypothesis of length contraction to explain the failure of optical and electrical experiments to detect motion relative to the aether (see Michelson–Morley experiment).[20] Poincaré was a constant interpreter (and sometimes friendly critic) of Lorentz's theory. Poincaré as a philosopher was interested in the "deeper meaning". Thus he interpreted Lorentz's theory and in so doing he came up with many insights that are now associated with special relativity. In The Measure of Time (1898), Poincaré said, " A little reflection is sufficient to understand that all these affirmations have by themselves no meaning. They can have one only as the result of a convention." He also argued that scientists have to set the constancy of the speed of light as a postulate to give physical theories the simplest form.[21] Based on these assumptions he discussed in 1900 Lorentz's "wonderful invention" of local time and remarked that it arose when moving clocks are synchronised by exchanging light signals assumed to travel with the same speed in both directions in a moving frame.[22]

Principle of relativity and Lorentz transformations

He discussed the "principle of relative motion" in two papers in 1900[22][23] and named it the principle of relativity in 1904, according to which no physical experiment can discriminate between a state of uniform motion and a state of rest.[24] In 1905 Poincaré wrote to Lorentz about Lorentz's paper of 1904, which Poincaré described as a "paper of supreme importance." In this letter he pointed out an error Lorentz had made when he had applied his transformation to one of Maxwell's equations, that for charge-occupied space, and also questioned the time dilation factor given by Lorentz.[25] In a second letter to Lorentz, Poincaré gave his own reason why Lorentz's time dilation factor was indeed correct after all: it was necessary to make the Lorentz transformation form a group and gave what is now known as the relativistic velocity-addition law.[26] Poincaré later delivered a paper at the meeting of the Academy of Sciences in Paris on 5 June 1905 in which these issues were addressed. In the published version of that he wrote:[27]

The essential point, established by Lorentz, is that the equations of the electromagnetic field are not altered by a certain transformation (which I will call by the name of Lorentz) of the form:

and showed that the arbitrary function must be unity for all (Lorentz had set by a different argument) to make the transformations form a group. In an enlarged version of the paper that appeared in 1906 Poincaré pointed out that the combination is invariant. He noted that a Lorentz transformation is merely a rotation in four-dimensional space about the origin by introducing as a fourth imaginary coordinate, and he used an early form of four-vectors.[28] Poincaré expressed a lack of interest in a four-dimensional reformulation of his new mechanics in 1907, because in his opinion the translation of physics into the language of four-dimensional geometry would entail too much effort for limited profit.[29] So it was Hermann Minkowski who worked out the consequences of this notion in 1907.

Mass–energy relation

Like others before, Poincaré (1900) discovered a relation between mass and electromagnetic energy. While studying the conflict between the action/reaction principle and Lorentz ether theory, he tried to determine whether the center of gravity still moves with a uniform velocity when electromagnetic fields are included.[22] He noticed that the action/reaction principle does not hold for matter alone, but that the electromagnetic field has its own momentum. Poincaré concluded that the electromagnetic field energy of an electromagnetic wave behaves like a fictitious fluid ("fluide fictif") with a mass density of E/c2. If the center of mass frame is defined by both the mass of matter and the mass of the fictitious fluid, and if the fictitious fluid is indestructible—it's neither created or destroyed—then the motion of the center of mass frame remains uniform. But electromagnetic energy can be converted into other forms of energy. So Poincaré assumed that there exists a non-electric energy fluid at each point of space, into which electromagnetic energy can be transformed and which also carries a mass proportional to the energy. In this way, the motion of the center of mass remains uniform. Poincaré said that one should not be too surprised by these assumptions, since they are only mathematical fictions.

However, Poincaré's resolution led to a paradox when changing frames: if a Hertzian oscillator radiates in a certain direction, it will suffer a recoil from the inertia of the fictitious fluid. Poincaré performed a Lorentz boost (to order v/c) to the frame of the moving source. He noted that energy conservation holds in both frames, but that the law of conservation of momentum is violated. This would allow perpetual motion, a notion which he abhorred. The laws of nature would have to be different in the frames of reference, and the relativity principle would not hold. Therefore, he argued that also in this case there has to be another compensating mechanism in the ether.

Poincaré himself came back to this topic in his St. Louis lecture (1904).[24] This time (and later also in 1908) he rejected[30] the possibility that energy carries mass and criticized the ether solution to compensate the above-mentioned problems:

The apparatus will recoil as if it were a cannon and the projected energy a ball, and that contradicts the principle of Newton, since our present projectile has no mass; it is not matter, it is energy. [..] Shall we say that the space which separates the oscillator from the receiver and which the disturbance must traverse in passing from one to the other, is not empty, but is filled not only with ether, but with air, or even in inter-planetary space with some subtile, yet ponderable fluid; that this matter receives the shock, as does the receiver, at the moment the energy reaches it, and recoils, when the disturbance leaves it? That would save Newton's principle, but it is not true. If the energy during its propagation remained always attached to some material substratum, this matter would carry the light along with it and Fizeau has shown, at least for the air, that there is nothing of the kind. Michelson and Morley have since confirmed this. We might also suppose that the motions of matter proper were exactly compensated by those of the ether; but that would lead us to the same considerations as those made a moment ago. The principle, if thus interpreted, could explain anything, since whatever the visible motions we could imagine hypothetical motions to compensate them. But if it can explain anything, it will allow us to foretell nothing; it will not allow us to choose between the various possible hypotheses, since it explains everything in advance. It therefore becomes useless.

He also discussed two other unexplained effects: (1) non-conservation of mass implied by Lorentz's variable mass , Abraham's theory of variable mass and Kaufmann's experiments on the mass of fast moving electrons and (2) the non-conservation of energy in the radium experiments of Madame Curie.

It was Albert Einstein's concept of mass–energy equivalence (1905) that a body losing energy as radiation or heat was losing mass of amount m = E/c2 that resolved[31] Poincaré's paradox, without using any compensating mechanism within the ether.[32] The Hertzian oscillator loses mass in the emission process, and momentum is conserved in any frame. However, concerning Poincaré's solution of the Center of Gravity problem, Einstein noted that Poincaré's formulation and his own from 1906 were mathematically equivalent.[33]

Poincaré and Einstein

Einstein's first paper on relativity was published three months after Poincaré's short paper,[27] but before Poincaré's longer version.[28] Einstein relied on the principle of relativity to derive the Lorentz transformations and used a similar clock synchronisation procedure (Einstein synchronisation) to the one that Poincaré (1900) had described, but Einstein's was remarkable in that it contained no references at all. Poincaré never acknowledged Einstein's work on special relativity. However, Einstein expressed sympathy with Poincaré's outlook obliquely in a letter to Hans Vaihinger on 3 May 1919, when Einstein considered Vaihinger's general outlook to be close to his own and Poincaré's to be close to Vaihinger's.[34] In public, Einstein acknowledged Poincaré posthumously in the text of a lecture in 1921 called Geometrie und Erfahrung in connection with non-Euclidean geometry, but not in connection with special relativity. A few years before his death, Einstein commented on Poincaré as being one of the pioneers of relativity, saying "Lorentz had already recognised that the transformation named after him is essential for the analysis of Maxwell's equations, and Poincaré deepened this insight still further ...."[35]

Algebra and number theory

Poincaré introduced group theory to physics, and was the first to study the group of Lorentz transformations.[36] He also made major contributions to the theory of discrete groups and their representations.

Topology

The subject is clearly defined by Felix Klein in his "Erlangen Program" (1872): the geometry invariants of arbitrary continuous transformation, a kind of geometry. The term "topology" was introduced, as suggested by Johann Benedict Listing, instead of previously used "Analysis situs". Some important concepts were introduced by Enrico Betti and Bernhard Riemann. But the foundation of this science, for a space of any dimension, was created by Poincaré. His first article on this topic appeared in 1894.[37]

His research in geometry led to the abstract topological definition of homotopy and homology. He also first introduced the basic concepts and invariants of combinatorial topology, such as Betti numbers and the fundamental group. Poincaré proved a formula relating the number of edges, vertices and faces of n-dimensional polyhedron (the Euler–Poincaré theorem) and gave the first precise formulation of the intuitive notion of dimension.[38]

Astronomy and celestial mechanics

Poincaré published two now classical monographs, "New Methods of Celestial Mechanics" (1892–1899) and "Lectures on Celestial Mechanics" (1905–1910). In them, he successfully applied the results of their research to the problem of the motion of three bodies and studied in detail the behavior of solutions (frequency, stability, asymptotic, and so on). They introduced the small parameter method, fixed points, integral invariants, variational equations, the convergence of the asymptotic expansions. Generalizing a theory of Bruns (1887), Poincaré showed that the three-body problem is not integrable. In other words, the general solution of the three-body problem can not be expressed in terms of algebraic and transcendental functions through unambiguous coordinates and velocities of the bodies. His work in this area were the first major achievements in celestial mechanics since Isaac Newton.[39]

These include the idea of Poincaré, who later became the base for mathematical "chaos theory" (see, in particular, the Poincaré recurrence theorem) and the general theory of dynamical systems. Poincaré authored important works on astronomy for the equilibrium figures gravitating rotating fluid. He introduced the important concept of bifurcation points, proved the existence of equilibrium figures of non-ellipsoid, including ring-shaped and pear-shaped figures, their stability. For this discovery, Poincaré received the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society (1900).[40]

Differential equations and mathematical physics

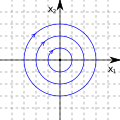

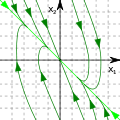

After defending his doctoral thesis on the study of singular points of the system of differential equations, Poincaré wrote a series of memoirs under the title "On curves defined by differential equations" (1881–1882).[41] In these articles, he built a new branch of mathematics, called "qualitative theory of differential equations". Poincaré showed that even if the differential equation can not be solved in terms of known functions, yet from the very form of the equation, a wealth of information about the properties and behavior of the solutions can be found. In particular, Poincaré investigated the nature of the trajectories of the integral curves in the plane, gave a classification of singular points (saddle, focus, center, node), introduced the concept of a limit cycle and the loop index, and showed that the number of limit cycles is always finite, except for some special cases. Poincaré also developed a general theory of integral invariants and solutions of the variational equations. For the finite-difference equations, he created a new direction – the asymptotic analysis of the solutions. He applied all these achievements to study practical problems of mathematical physics and celestial mechanics, and the methods used were the basis of its topological works.[42][43]

- The singular points of the integral curves

-

Saddle

-

Focus

-

Center

-

Node

Assessments

Poincaré's work in the development of special relativity is well recognised,[31] though most historians stress that despite many similarities with Einstein's work, the two had very different research agendas and interpretations of the work.[44] Poincaré developed a similar physical interpretation of local time and noticed the connection to signal velocity, but contrary to Einstein he continued to use the ether-concept in his papers and argued that clocks in the ether show the "true" time, and moving clocks show the local time. So Poincaré tried to keep the relativity principle in accordance with classical concepts, while Einstein developed a mathematically equivalent kinematics based on the new physical concepts of the relativity of space and time.[45][46][47][48][49]

While this is the view of most historians, a minority go much further, such as E. T. Whittaker, who held that Poincaré and Lorentz were the true discoverers of Relativity.[50]

Character

Poincaré's work habits have been compared to a bee flying from flower to flower. Poincaré was interested in the way his mind worked; he studied his habits and gave a talk about his observations in 1908 at the Institute of General Psychology in Paris. He linked his way of thinking to how he made several discoveries.

The mathematician Darboux claimed he was un intuitif (intuitive), arguing that this is demonstrated by the fact that he worked so often by visual representation. He did not care about being rigorous and disliked logic. [citation needed] (Despite this opinion, Jacques Hadamard wrote that Poincaré's research demonstrated marvelous clarity.[51] and Poincaré himself wrote that he believed that logic was not a way to invent but a way to structure ideas and that logic limits ideas.)

Toulouse's characterisation

Poincaré's mental organisation was not only interesting to Poincaré himself but also to Édouard Toulouse, a psychologist of the Psychology Laboratory of the School of Higher Studies in Paris. Toulouse wrote a book entitled Henri Poincaré (1910).[52][53] In it, he discussed Poincaré's regular schedule:

- He worked during the same times each day in short periods of time. He undertook mathematical research for four hours a day, between 10 a.m. and noon then again from 5 p.m. to 7 p.m.. He would read articles in journals later in the evening.

- His normal work habit was to solve a problem completely in his head, then commit the completed problem to paper.

- He was ambidextrous and nearsighted.

- His ability to visualise what he heard proved particularly useful when he attended lectures, since his eyesight was so poor that he could not see properly what the lecturer wrote on the blackboard.

These abilities were offset to some extent by his shortcomings:

- He was physically clumsy and artistically inept.

- He was always in a rush and disliked going back for changes or corrections.

- He never spent a long time on a problem since he believed that the subconscious would continue working on the problem while he consciously worked on another problem.

In addition, Toulouse stated that most mathematicians worked from principles already established while Poincaré started from basic principles each time (O'Connor et al., 2002).

His method of thinking is well summarised as:

Habitué à négliger les détails et à ne regarder que les cimes, il passait de l'une à l'autre avec une promptitude surprenante et les faits qu'il découvrait se groupant d'eux-mêmes autour de leur centre étaient instantanément et automatiquement classés dans sa mémoire. (Accustomed to neglecting details and to looking only at mountain tops, he went from one peak to another with surprising rapidity, and the facts he discovered, clustering around their center, were instantly and automatically pigeonholed in his memory.)

— Belliver (1956)

Attitude towards transfinite numbers

Poincaré was dismayed by Georg Cantor's theory of transfinite numbers, and referred to it as a "disease" from which mathematics would eventually be cured.[54] Poincaré said, "There is no actual infinite; the Cantorians have forgotten this, and that is why they have fallen into contradiction."[55]

Honours

Awards

- Oscar II, King of Sweden's mathematical competition (1887)

- Foreign member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (1897)[56]

- American Philosophical Society 1899

- Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society of London (1900)

- Bolyai Prize in 1905

- Matteucci Medal 1905

- French Academy of Sciences 1906

- Académie française 1909

- Bruce Medal (1911)

Named after him

- Institut Henri Poincaré (mathematics and theoretical physics center)

- Poincaré Prize (Mathematical Physics International Prize)

- Annales Henri Poincaré (Scientific Journal)

- Poincaré Seminar (nicknamed "Bourbaphy")

- The crater Poincaré on the Moon

- Asteroid 2021 Poincaré

- List of things named after Henri Poincaré

Henri Poincaré did not receive the Nobel Prize in Physics, but he had influential advocates like Henri Becquerel or committee member Gösta Mittag-Leffler.[57][58] The nomination archive reveals that Poincaré received a total of 51 nominations between 1904 and 1912, the year of his death.[59] Of the 58 nominations for the 1910 Nobel Prize, 34 named Poincaré.[59] Nominators included Nobel laureates Hendrik Lorentz and Pieter Zeeman (both of 1902), Marie Curie (of 1903), Albert Michelsen (of 1907), Gabriel Lippmann (of 1908) and Guglielmo Marconi (of 1909).[59]

The fact that renowned theoretical physicists like Poincaré, Boltzmann or Gibbs were not awarded the Nobel Prize is seen as evidence that the Nobel committee had more regard for experimentation than theory.[60][61] In Poincaré's case, several of those who nominated him pointed out that the greatest problem was to name a specific discovery, invention, or technique.[57]

Philosophy

Poincaré had philosophical views opposite to those of Bertrand Russell and Gottlob Frege, who believed that mathematics was a branch of logic. Poincaré strongly disagreed, claiming that intuition was the life of mathematics. Poincaré gives an interesting point of view in his book Science and Hypothesis:

For a superficial observer, scientific truth is beyond the possibility of doubt; the logic of science is infallible, and if the scientists are sometimes mistaken, this is only from their mistaking its rule.

Poincaré believed that arithmetic is a synthetic science. He argued that Peano's axioms cannot be proven non-circularly with the principle of induction (Murzi, 1998), therefore concluding that arithmetic is a priori synthetic and not analytic. Poincaré then went on to say that mathematics cannot be deduced from logic since it is not analytic. His views were similar to those of Immanuel Kant (Kolak, 2001, Folina 1992). He strongly opposed Cantorian set theory, objecting to its use of impredicative definitions.

However, Poincaré did not share Kantian views in all branches of philosophy and mathematics. For example, in geometry, Poincaré believed that the structure of non-Euclidean space can be known analytically. Poincaré held that convention plays an important role in physics. His view (and some later, more extreme versions of it) came to be known as "conventionalism". Poincaré believed that Newton's first law was not empirical but is a conventional framework assumption for mechanics (Gargani, 2012).[62] He also believed that the geometry of physical space is conventional. He considered examples in which either the geometry of the physical fields or gradients of temperature can be changed, either describing a space as non-Euclidean measured by rigid rulers, or as a Euclidean space where the rulers are expanded or shrunk by a variable heat distribution. However, Poincaré thought that we were so accustomed to Euclidean geometry that we would prefer to change the physical laws to save Euclidean geometry rather than shift to a non-Euclidean physical geometry.[63]

Free will

Poincaré's famous lectures before the Société de Psychologie in Paris (published as Science and Hypothesis, The Value of Science, and Science and Method) were cited by Jacques Hadamard as the source for the idea that creativity and invention consist of two mental stages, first random combinations of possible solutions to a problem, followed by a critical evaluation.[64]

Although he most often spoke of a deterministic universe, Poincaré said that the subconscious generation of new possibilities involves chance.

It is certain that the combinations which present themselves to the mind in a kind of sudden illumination after a somewhat prolonged period of unconscious work are generally useful and fruitful combinations... all the combinations are formed as a result of the automatic action of the subliminal ego, but those only which are interesting find their way into the field of consciousness... A few only are harmonious, and consequently at once useful and beautiful, and they will be capable of affecting the geometrician's special sensibility I have been speaking of; which, once aroused, will direct our attention upon them, and will thus give them the opportunity of becoming conscious... In the subliminal ego, on the contrary, there reigns what I would call liberty, if one could give this name to the mere absence of discipline and to disorder born of chance.[65]

Poincaré's two stages—random combinations followed by selection—became the basis for Daniel Dennett's two-stage model of free will.[66]

See also

Concepts

- Poincaré complex – an abstraction of the singular chain complex of a closed, orientable manifold.

- Poincaré duality

- Poincaré disk model

- Poincaré group

- Poincaré inequality

- Poincaré map

- Poincaré residue

- Poincaré series (modular form)

- Poincaré space

- Poincaré metric

- Poincaré series

- Poincaré sphere

- Poincaré–Lindstedt method

- Poincaré plot

- Poincaré half-plane model

- Poincaré–Steklov operator

- Poincaré–Lindstedt perturbation theory

- Poincaré–Lelong equation

Theorems

- Poincaré's recurrence theorem: certain systems will, after a sufficiently long but finite time, return to a state very close to the initial state.

- Poincaré–Bendixson theorem: a statement about the long-term behaviour of orbits of continuous dynamical systems on the plane, cylinder, or two-sphere.

- Poincaré–Hopf theorem: a generalization of the hairy-ball theorem, which states that there is no smooth vector field on a sphere having no sources or sinks.

- Poincaré–Lefschetz duality theorem: a version of Poincaré duality in geometric topology, applying to a manifold with boundary

- Poincaré separation theorem: gives the upper and lower bounds of eigenvalues of a real symmetric matrix B'AB that can be considered as the orthogonal projection of a larger real symmetric matrix A onto a linear subspace spanned by the columns of B.

- Poincaré–Birkhoff theorem: every area-preserving, orientation-preserving homeomorphism of an annulus that rotates the two boundaries in opposite directions has at least two fixed points.

- Poincaré–Birkhoff–Witt theorem: an explicit description of the universal enveloping algebra of a Lie algebra.

- Poincaré conjecture (now a theorem): Every simply connected, closed 3-manifold is homeomorphic to the 3-sphere.

- Poincaré–Miranda theorem: a generalization of the intermediate value theorem to n dimensions.

Other

References

- This article incorporates material from Jules Henri Poincaré on PlanetMath, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License.

Footnotes and primary sources

- ^ "Poincaré's Philosophy of Mathematics": entry in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ "Poincaré pronunciation: How to pronounce Poincaré in French". forvo.com. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ^ "Poincaré pronunciation: How to pronounce Poincaré in French". pronouncekiwi.com. Retrieved 25 December 2015.

- ^ Ginoux, J. M.; Gerini, C. (2013). Henri Poincaré: A Biography Through the Daily Papers. World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-4556-61-3.

- ^ Hadamard, Jacques (July 1922). "The early scientific work of Henri Poincaré". The Rice Institute Pamphlet. 9 (3): 111–183.

- ^ Belliver, 1956

- ^ Sagaret, 1911

- ^ The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy Jules Henri Poincaré article by Mauro Murzi – Retrieved November 2006.

- ^ O'Connor et al., 2002

- ^ Carl, 1968

- ^ F. Verhulst

- ^ Sageret, 1911

- ^ see Galison 2003

- ^ Lorentz, Poincaré et Einstein

- ^ Mathematics Genealogy Project North Dakota State University. Retrieved April 2008.

- ^ McCormmach, Russell (Spring 1967), "Henri Poincaré and the Quantum Theory", Isis, 58 (1): 37–55, doi:10.1086/350182

- ^ Irons, F. E. (August 2001), "Poincaré's 1911–12 proof of quantum discontinuity interpreted as applying to atoms", American Journal of Physics, 69 (8): 879–884, Bibcode:2001AmJPh..69..879I, doi:10.1119/1.1356056

- ^ Diacu, F. (1996), "The solution of the n-body Problem", The Mathematical Intelligencer, 18 (3): 66–70, doi:10.1007/BF03024313

- ^ Hsu, Jong-Ping; Hsu, Leonardo (2006), A broader view of relativity: general implications of Lorentz and Poincaré invariance, vol. 10, World Scientific, p. 37, ISBN 981-256-651-1, Section A5a, p 37

- ^ Lorentz, H.A. (1895), , Leiden: E.J. Brill

- ^ Poincaré, H. (1898), , Revue de métaphysique et de morale, 6: 1–13

- ^ a b c Poincaré, H. (1900), , Archives néerlandaises des sciences exactes et naturelles, 5: 252–278. See also the English translation

- ^ Poincaré, H. (1900), "Les relations entre la physique expérimentale et la physique mathématique", Revue générale des sciences pures et appliquées, 11: 1163–1175. Reprinted in "Science and Hypothesis", Ch. 9–10.

- ^ a b Poincaré, Henri (1904/6), , The Foundations of Science (The Value of Science), New York: Science Press, pp. 297–320

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ "Letter from Poincaré to Lorentz, Mai 1905". henripoincarepapers.univ-lorraine.fr. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ^ "Letter from Poincaré to Lorentz, Mai 1905". henripoincarepapers.univ-lorraine.fr. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ^ a b Poincaré, H. (1905), "Sur la dynamique de l'électron (On the Dynamics of the Electron)", Comptes Rendus, 140: 1504–1508 (Wikisource translation)

- ^ a b Poincaré, H. (1906), "Sur la dynamique de l'électron (On the Dynamics of the Electron)", Rendiconti del Circolo matematico Rendiconti del Circolo di Palermo, 21: 129–176, doi:10.1007/BF03013466 (Wikisource translation)

- ^ Walter (2007), Secondary sources on relativity

- ^ Miller 1981, Secondary sources on relativity

- ^ a b Darrigol 2005, Secondary sources on relativity

- ^ Einstein, A. (1905b), "Ist die Trägheit eines Körpers von dessen Energieinhalt abhängig?" (PDF), Annalen der Physik, 18: 639–643, Bibcode:1905AnP...323..639E, doi:10.1002/andp.19053231314. See also English translation.

- ^ Einstein, A. (1906), "Das Prinzip von der Erhaltung der Schwerpunktsbewegung und die Trägheit der Energie" (PDF), Annalen der Physik, 20 (8): 627–633, Bibcode:1906AnP...325..627E, doi:10.1002/andp.19063250814

- ^ "The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein". Princeton U.P. Retrieved 13 December 2014. See also this letter, with commentary, in Sass, Hans-Martin (1979). "Einstein über "wahre Kultur" und die Stellung der Geometrie im Wissenschaftssystem: Ein Brief Albert Einsteins an Hans Vaihinger vom Jahre 1919". Zeitschrift für allgemeine Wissenschaftstheorie (in German). 10 (2): 316–319. doi:10.1007/bf01802352. JSTOR 25170513.

- ^ Darrigol 2004, Secondary sources on relativity

- ^ Poincaré, Selected works in three volumes. page = 682

- ^ D. Stillwell, Mathematics and its history. pages = 419–435

- ^ PS Aleksandrov, Poincaré and topology. pages = 27–81

- ^ D. Stillwell, Mathematics and its history. pages = 434

- ^ A. Kozenko, The theory of planetary figures, pages = 25–26

- ^ French: "Mémoire sur les courbes définies par une équation différentielle"

- ^ Kolmogorov, AP Yushkevich, Mathematics of the 19th century Vol = 3. page = 283 ISBN 978-3764358457

- ^ Kolmogorov, AP Yushkevich, Mathematics of the 19th century. pages = 162–174

- ^ Galison 2003 and Kragh 1999, Secondary sources on relativity

- ^ Holton (1988), 196–206

- ^ Hentschel (1990), 3–13

- ^ Miller (1981), 216–217

- ^ Darrigol (2005), 15–18

- ^ Katzir (2005), 286–288

- ^ Whittaker 1953, Secondary sources on relativity

- ^ J. Hadamard. L'oeuvre de H. Poincaré. Acta Mathematica, 38 (1921), p. 208

- ^ Toulouse, E.,1910. Henri Poincaré

- ^ Toulouse, E. (2013). Henri Poincare. MPublishing. ISBN 9781418165062. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ Dauben 1979, p. 266.

- ^ Van Heijenoort, Jean (1967), From Frege to Gödel: a source book in mathematical logic, 1879–1931, Harvard University Press, p. 190, ISBN 0-674-32449-8, p 190

- ^ "Jules Henri Poincaré (1854 - 1912)". Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ^ a b Gray, Jeremy (2013). "The Campaign for Poincaré". Henri Poincaré: A Scientific Biography. Princeton University Press. pp. 194–196.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Crawford, Elizabeth (25 November 1987). The Beginnings of the Nobel Institution: The Science Prizes, 1901-1915. Cambridge University Press. pp. 141–142.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b c "Nomination database". Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ^ Crawford, Elizabeth (13 November 1998). "Nobel: Always the Winners, Never the Losers". Science. 282 (5392): 1256–1257. doi:10.1126/science.282.5392.1256.

- ^ Nastasi, Pietro (16 May 2013). "A Nobel Prize for Poincaré?" (PDF). Lettera Matematica. 1 (1–2): 79–82. doi:10.1007/s40329-013-0005-1. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ^ Gargani Julien (2012), Poincaré, le hasard et l’étude des systèmes complexes, L’Harmattan, p. 124

- ^ Poincaré, Henri (2007), Science and Hypothesis, Cosimo, Inc. Press, p. 50, ISBN 978-1-60206-505-5

- ^ Hadamard, Jacques. An Essay on the Psychology of Invention in the Mathematical Field. Princeton Univ Press (1945)

- ^ Science and Method, Chapter 3, Mathematical Discovery, 1914, pp.58

- ^ Dennett, Daniel C. 1978. Brainstorms: Philosophical Essays on Mind and Psychology. The MIT Press, p.293

- ^ "Structural Realism": entry by James Ladyman in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Poincaré's writings in English translation

Popular writings on the philosophy of science:

- Poincaré, Henri (1902–1908), The Foundations of Science, New York: Science Press; reprinted in 1921; This book includes the English translations of Science and Hypothesis (1902), The Value of Science (1905), Science and Method (1908).

- 1904. Science and Hypothesis, The Walter Scott Publishing Co.

- 1913. "The New Mechanics," The Monist, Vol. XXIII.

- 1913. "The Relativity of Space," The Monist, Vol. XXIII.

- 1913. Last Essays., New York: Dover reprint, 1963

- 1956. Chance. In James R. Newman, ed., The World of Mathematics (4 Vols).

- 1958. The Value of Science, New York: Dover.

- 1895. Analysis Situs (PDF). The first systematic study of topology.

- 1892–99. New Methods of Celestial Mechanics, 3 vols. English trans., 1967. ISBN 1-56396-117-2.

- 1905. "The Capture Hypothesis of J. J. See," The Monist, Vol. XV.

- 1905–10. Lessons of Celestial Mechanics.

On the philosophy of mathematics:

- Ewald, William B., ed., 1996. From Kant to Hilbert: A Source Book in the Foundations of Mathematics, 2 vols. Oxford Univ. Press. Contains the following works by Poincaré:

- 1894, "On the Nature of Mathematical Reasoning," 972–81.

- 1898, "On the Foundations of Geometry," 982–1011.

- 1900, "Intuition and Logic in Mathematics," 1012–20.

- 1905–06, "Mathematics and Logic, I–III," 1021–70.

- 1910, "On Transfinite Numbers," 1071–74.

- 1905. "The Principles of Mathematical Physics," The Monist, Vol. XV.

- 1910. "The Future of Mathematics," The Monist, Vol. XX.

- 1910. "Mathematical Creation," The Monist, Vol. XX.

Other:

- 1904. Maxwell's Theory and Wireless Telegraphy, New York, McGraw Publishing Company.

- 1905. "The New Logics," The Monist, Vol. XV.

- 1905. "The Latest Efforts of the Logisticians," The Monist, Vol. XV.

General references

- Bell, Eric Temple, 1986. Men of Mathematics (reissue edition). Touchstone Books. ISBN 0-671-62818-6.

- Belliver, André, 1956. Henri Poincaré ou la vocation souveraine. Paris: Gallimard.

- Bernstein, Peter L, 1996. "Against the Gods: A Remarkable Story of Risk". (p. 199–200). John Wiley & Sons.

- Boyer, B. Carl, 1968. A History of Mathematics: Henri Poincaré, John Wiley & Sons.

- Grattan-Guinness, Ivor, 2000. The Search for Mathematical Roots 1870–1940. Princeton Uni. Press.

- Dauben, Joseph (2004) [1993], "Georg Cantor and the Battle for Transfinite Set Theory" (PDF), Proceedings of the 9th ACMS Conference (Westmont College, Santa Barbara, CA), pp. 1–22. Internet version published in Journal of the ACMS 2004.

- Folina, Janet, 1992. Poincaré and the Philosophy of Mathematics. Macmillan, New York.

- Gray, Jeremy, 1986. Linear differential equations and group theory from Riemann to Poincaré, Birkhauser ISBN 0-8176-3318-9

- Gray, Jeremy, 2013. Henri Poincaré: A scientific biography. Princeton University Press ISBN 978-0-691-15271-4

- Jean Mawhin (October 2005), "Henri Poincaré. A Life in the Service of Science" (PDF), Notices of the AMS, 52 (9): 1036–1044

- Kolak, Daniel, 2001. Lovers of Wisdom, 2nd ed. Wadsworth.

- Gargani, Julien, 2012. Poincaré, le hasard et l’étude des systèmes complexes, L’Harmattan.

- Murzi, 1998. "Henri Poincaré".

- O'Connor, J. John, and Robertson, F. Edmund, 2002, "Jules Henri Poincaré". University of St. Andrews, Scotland.

- Peterson, Ivars, 1995. Newton's Clock: Chaos in the Solar System (reissue edition). W H Freeman & Co. ISBN 0-7167-2724-2.

- Sageret, Jules, 1911. Henri Poincaré. Paris: Mercure de France.

- Toulouse, E.,1910. Henri Poincaré.—(Source biography in French) at University of Michigan Historic Math Collection.

- Verhulst, Ferdinand, 2012 Henri Poincaré. Impatient Genius. N.Y.: Springer.

Secondary sources to work on relativity

- Cuvaj, Camillo (1969), "Henri Poincaré's Mathematical Contributions to Relativity and the Poincaré Stresses", American Journal of Physics, 36 (12): 1102–1113, Bibcode:1968AmJPh..36.1102C, doi:10.1119/1.1974373

- Darrigol, O. (1995), "Henri Poincaré's criticism of Fin De Siècle electrodynamics", Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, 26 (1): 1–44, doi:10.1016/1355-2198(95)00003-C

- Darrigol, O. (2000), Electrodynamics from Ampére to Einstein, Oxford: Clarendon Press, ISBN 0-19-850594-9

- Darrigol, O. (2004), "The Mystery of the Einstein–Poincaré Connection", Isis, 95 (4): 614–626, doi:10.1086/430652, PMID 16011297

- Darrigol, O. (2005), "The Genesis of the theory of relativity" (PDF), Séminaire Poincaré, 1: 1–22, doi:10.1007/3-7643-7436-5_1

- Galison, P. (2003), Einstein's Clocks, Poincaré's Maps: Empires of Time, New York: W.W. Norton, ISBN 0-393-32604-7

- Giannetto, E. (1998), "The Rise of Special Relativity: Henri Poincaré's Works Before Einstein", Atti del XVIII congresso di storia della fisica e dell'astronomia: 171–207

- Giedymin, J. (1982), Science and Convention: Essays on Henri Poincaré's Philosophy of Science and the Conventionalist Tradition, Oxford: Pergamon Press, ISBN 0-08-025790-9

- Goldberg, S. (1967), "Henri Poincaré and Einstein's Theory of Relativity", American Journal of Physics, 35 (10): 934–944, Bibcode:1967AmJPh..35..934G, doi:10.1119/1.1973643

- Goldberg, S. (1970), "Poincaré's silence and Einstein's relativity", British journal for the history of science, 5: 73–84, doi:10.1017/S0007087400010633

- Holton, G. (1988) [1973], "Poincaré and Relativity", Thematic Origins of Scientific Thought: Kepler to Einstein, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-87747-0

- Katzir, S. (2005), "Poincaré's Relativistic Physics: Its Origins and Nature", Phys. Perspect., 7 (3): 268–292, Bibcode:2005PhP.....7..268K, doi:10.1007/s00016-004-0234-y

- Keswani, G.H., Kilmister, C.W. (1983), "Intimations of Relativity: Relativity Before Einstein", Brit. J. Phil. Sci., 34 (4): 343–354, doi:10.1093/bjps/34.4.343

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kragh, H. (1999), Quantum Generations: A History of Physics in the Twentieth Century, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-09552-3

- Langevin, P. (1913), "L'œuvre d'Henri Poincaré: le physicien", Revue de métaphysique et de morale, 21: 703

- Macrossan, M. N. (1986), "A Note on Relativity Before Einstein", Brit. J. Phil. Sci., 37: 232–234, doi:10.1093/bjps/37.2.232

- Miller, A.I. (1973), "A study of Henri Poincaré's "Sur la Dynamique de l'Electron", Arch. Hist. Exact Sci., 10 (3–5): 207–328, doi:10.1007/BF00412332

- Miller, A.I. (1981), Albert Einstein's special theory of relativity. Emergence (1905) and early interpretation (1905–1911), Reading: Addison–Wesley, ISBN 0-201-04679-2

- Miller, A.I. (1996), "Why did Poincaré not formulate special relativity in 1905?", in Jean-Louis Greffe, Gerhard Heinzmann, Kuno Lorenz (ed.), Henri Poincaré : science et philosophie, Berlin, pp. 69–100

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Schwartz, H. M. (1971), "Poincaré's Rendiconti Paper on Relativity. Part I", American Journal of Physics, 39 (7): 1287–1294, Bibcode:1971AmJPh..39.1287S, doi:10.1119/1.1976641

- Schwartz, H. M. (1972), "Poincaré's Rendiconti Paper on Relativity. Part II", American Journal of Physics, 40 (6): 862–872, Bibcode:1972AmJPh..40..862S, doi:10.1119/1.1986684

- Schwartz, H. M. (1972), "Poincaré's Rendiconti Paper on Relativity. Part III", American Journal of Physics, 40 (9): 1282–1287, Bibcode:1972AmJPh..40.1282S, doi:10.1119/1.1986815

- Scribner, C. (1964), "Henri Poincaré and the principle of relativity", American Journal of Physics, 32 (9): 672–678, Bibcode:1964AmJPh..32..672S, doi:10.1119/1.1970936

- Walter, S. (2005), Renn, J. (ed.), Albert Einstein, Chief Engineer of the Universe: 100 Authors for Einstein, Berlin: Wiley-VCH: 162–165

{{citation}}:|contribution=ignored (help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - Walter, S. (2007), Renn, J. (ed.), The Genesis of General Relativity, 3, Berlin: Springer: 193–252

{{citation}}:|contribution=ignored (help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - Zahar, E. (2001), Poincaré's Philosophy: From Conventionalism to Phenomenology, Chicago: Open Court Pub Co, ISBN 0-8126-9435-X

- Non-mainstream

- Keswani, G.H., (1965), "Origin and Concept of Relativity, Part I", Brit. J. Phil. Sci., 15 (60): 286–306, doi:10.1093/bjps/XV.60.286

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Keswani, G.H., (1965), "Origin and Concept of Relativity, Part II", Brit. J. Phil. Sci., 16 (61): 19–32, doi:10.1093/bjps/XVI.61.19

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Keswani, G.H., (11966), "Origin and Concept of Relativity, Part III", Brit. J. Phil. Sci., 16 (64): 273–294, doi:10.1093/bjps/XVI.64.273

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: year (link) - Leveugle, J. (2004), La Relativité et Einstein, Planck, Hilbert—Histoire véridique de la Théorie de la Relativitén, Pars: L'Harmattan

- Logunov, A.A. (2004), Henri Poincaré and relativity theory, Moscow: Nauka, arXiv:physics/0408077, Bibcode:2004physics...8077L, ISBN 5-02-033964-4

- Whittaker, E.T. (1953), "The Relativity Theory of Poincaré and Lorentz", A History of the Theories of Aether and Electricity: The Modern Theories 1900–1926, London: Nelson

External links

- Works by Henri Poincaré at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Henri Poincaré at the Internet Archive

- Works by Henri Poincaré at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy: "Henri Poincaré"—by Mauro Murzi.

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy: "Poincaré’s Philosophy of Mathematics"—by Janet Folina.

- Henri Poincaré at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- Henri Poincaré on Information Philosopher

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Henri Poincaré", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- A timeline of Poincaré's life University of Lorraine (in French).

- Bruce Medal page

- Collins, Graham P., "Henri Poincaré, His Conjecture, Copacabana and Higher Dimensions," Scientific American, 9 June 2004.

- BBC in Our Time, "Discussion of the Poincaré conjecture," 2 November 2006, hosted by Melvynn Bragg. Archive index at the Wayback Machine

- Poincare Contemplates Copernicus at MathPages

- High Anxieties – The Mathematics of Chaos (2008) BBC documentary directed by David Malone looking at the influence of Poincaré's discoveries on 20th Century mathematics.

- 1854 births

- 1912 deaths

- 19th-century French mathematicians

- 20th-century French philosophers

- 20th-century mathematicians

- Algebraic geometers

- Burials at Montparnasse Cemetery

- Chaos theorists

- Corps des mines

- Corresponding Members of the St Petersburg Academy of Sciences

- École Polytechnique alumni

- French agnostics

- French mathematicians

- French military personnel of the Franco-Prussian War

- French physicists

- Geometers

- Mathematical analysts

- Members of the Académie française

- Members of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Mines ParisTech alumni

- Officers of the French Academy of Sciences

- People from Nancy

- Philosophers of science

- Recipients of the Bruce Medal

- Recipients of the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society

- Relativity theorists

- Thermodynamicists

- Topologists

- University of Paris faculty

- French male writers

- Deaths from embolism

- Dynamical systems theorists