Human rights in the Soviet Union

| Politics of the Soviet Union |

|---|

|

|

|

The Soviet Union was a socialist federation where members of the Communist Party held all key positions in the institutions of the state and other organizations. Civil and political rights were severely limited and the entire population was mobilized in support of the state ideology and policies. Independent political activities were not tolerated, including the involvement of people with free labour unions, private corporations, non-sanctioned churches or opposition political parties. The state's proclaimed adherence to Marxism-Leninism restricted any rights of citizens to private property. Yet this situation, as the Soviet human rights activists of the 1960s pointed out, was in direct contrast to the formal provisions of the 1936 Constitution, in operation until the late 1970s. This guaranteed, among others, the right to freedom of assembly and association.

Regime

The regime maintained itself in political power by means of the secret police, propaganda disseminated through the state-controlled mass media, personality cult, restriction of free discussion and criticism, the use of mass surveillance, political purges and persecution of specific groups of people. In the new 1977 Constitution the Party was, for the first time, openly and formally declared the leading force in the country.

Soviet concept of human rights and legal system

According to Universal Declaration of Human Rights, human rights are the "basic rights and freedoms to which all humans are entitled.",[1] including the right to life and liberty, freedom of expression, and equality before the law; and social, cultural and economic rights, including the right to participate in culture, the right to food, the right to work, and the right to education.

However the Soviet conception of human rights was very different from conceptions prevalent in the West. According to Western legal theory, "it is the individual who is the beneficiary of human rights which are to be asserted against the government", whereas Soviet law claimed the opposite.[2] The Soviet state was considered as the source of human rights.[3] Therefore, the Soviet legal system regarded law as an arm of politics and courts as agencies of the government.[4] Extensive extra-judiciary powers were given to the Soviet secret police agencies. The regime abolished Western rule of law, civil liberties, protection of law and guarantees of property[5][6] which were considered as examples of "bourgeois morality" by the Soviet law theorists such as Andrey Vyshinsky.[7] According to Vladimir Lenin, the purpose of socialist courts was "not to eliminate terror ... but to substantiate it and legitimize in principle".[4]

Historian Robert Conquest described the Soviet electoral system as "a set of phantom institutions and arrangements which put a human face on the hideous realities: a model constitution adopted in a worst period of terror and guaranteeing human rights, elections in which there was only one candidate, and in which 99 percent voted; a parliament at which no hand was ever raised in opposition or abstention."[8] Sergei Kovalev recalled "the famous article 125 of Constitution which enumerated all main citizen and political rights" in Soviet Union. But when he and other prisoners attempted to use this as a legal base for their abuse complaints, their prosecutor's argument was that "the Constitution was written not for you, but for American Negros, so that they know how happy lives Soviet citizens have".[9]

Crime was determined not as the infraction of law, but as any action which could threaten the Soviet state and society. For example, a desire to make a profit could be interpreted as a counter-revolutionary activity punishable by death.[4] The liquidation and deportation of millions peasants in 1928–31 was carried out within the terms of Soviet Civil Code.[4] Some Soviet legal scholars even asserted that "criminal repression" may be applied in the absence of guilt.".[4] Martin Latsis, chief of the Ukrainian Cheka explained: "Do not look in the file of incriminating evidence to see whether or not the accused rose up against the Soviets with arms or words. Ask him instead to which class he belongs, what is his background, his education, his profession. These are the questions that will determine the fate of the accused. That is the meaning and essence of the Red Terror."[10]

The purpose of public trials was "not to demonstrate the existence or absence of a crime – that was predetermined by the appropriate party authorities – but to provide yet another forum for political agitation and propaganda for the instruction of the citizenry (see Moscow Trials for example). Defense lawyers, who had to be party members, were required to take their client's guilt for granted..."[4]

Freedom of political expression

In the 1930s and 1940s, political repression was practiced by the Soviet secret police services, OGPU and NKVD.[11] An extensive network of civilian informants – either volunteers, or those forcibly recruited – was used to collect intelligence for the government and report cases of suspected dissent.[12]

Soviet political repression was a de facto and de jure system of persecution and prosecution of people who were or perceived to be enemies of the Soviet system.[citation needed] Its theoretical basis was the theory of Marxism concerning class struggle. The terms "repression", "terror", and other strong words were official working terms, since the dictatorship of the proletariat was supposed to suppress the resistance of other social classes, which Marxism considered antagonistic to the class of the proletariat. The legal basis of the repression was formalized into Article 58 in the code of the RSFSR and similar articles for other Soviet republics. Aggravation of class struggle under socialism was proclaimed during the Stalinist terror.

Freedom of literary and scientific expression

Censorship in the Soviet Union was pervasive and strictly enforced.[13] This gave rise to Samizdat, a clandestine copying and distribution of government-suppressed literature. Art, literature, education, and science were placed under strict ideological scrutiny, since they were supposed to serve the interests of the victorious proletariat. Socialist realism is an example of such teleologically-oriented art that promoted socialism and communism. All humanities and social sciences were tested for strict accordance with historical materialism.

All natural sciences were to be founded on the philosophical base of dialectical materialism. Many scientific disciplines, such as genetics, cybernetics, and comparative linguistics, were suppressed in the Soviet Union during some periods, condemned as "bourgeois pseudoscience". At one point Lysenkoism, which many consider a pseudoscience, was favored in agriculture and biology. In the 1930s and 1940s, many prominent scientists were declared to be "wreckers" or enemies of the people and imprisoned. Some scientists worked as prisoners in "Sharashkas" (research and development laboratories within the Gulag labor camp system).

Every large enterprise and institution of the Soviet Union had a First Department that reported to the KGB; the First Department was responsible for secrecy and political security in the workplace.[citation needed]

According to the Soviet Criminal Code, agitation or propaganda carried on for the purpose of weakening Soviet authority, or circulating materials or literature that defamed the Soviet State and social system were punishable by imprisonment for a term of 2–5 years; for a second offense, punishable for a term of 3–10 years.[14]

Right to vote

According to communist ideologists, the Soviet political system was a true democracy, where workers' councils ("soviets") represented the will of the working class. In particular, the Soviet Constitution of 1936 guaranteed direct universal suffrage with the secret ballot.[15] Practice, however, departed from principle. For example, all candidates had been selected by Communist Party organizations before the June 1987 elections.

Economic rights

Personal property was allowed, with certain limitations. Real property mostly belonged to the State.[16] Health, housing, education, and nutrition were guaranteed through the provision of full employment and economic welfare structures implemented in the workplace.[16]

However, these guarantees were not always met in practice. For instance, over five million people lacked adequate nutrition and starved to death during the Soviet famine of 1932–1933, one of several Soviet famines.[17] The 1932–33 famine was caused primarily by Soviet-mandated collectivization.[18]

Economic protection was also extended to the elderly and the disabled through the payment of pensions and benefits.[19]

Freedoms of assembly and association

Freedom of assembly and of association were limited.[citation needed] Workers were not allowed to organize free trade unions. All existing trade unions were organized and controlled by the state.[20] All political youth organizations, such as Pioneer movement and Komsomol served to enforce the policies of the Communist Party. Participation in non-authorized political organizations could result in imprisonment.[14] Organizing in camps could bring the death penalty.[14][need quotation to verify]

Freedom of religion

The Soviet Union promoted atheism. Toward that end, the Communist regime confiscated church property, ridiculed religion, harassed believers, and propagated atheism in the schools. Actions toward particular religions, however, were determined by State interests, and most organized religions were never outlawed outright.

Some actions against Orthodox priests and believers included torture; being sent to prison camps, labour camps, or mental hospitals; and execution.[21][22][23][24] Many Orthodox (along with peoples of other faiths) were also subjected to psychological punishment or torture and mind control experimentation in an attempt to force them give up their religious convictions (see Punitive psychiatry in the Soviet Union).[22][23][25][26]

Practicing Orthodox Christians were restricted from prominent careers and membership in communist organizations (e.g. the party and the Komsomol). Anti-religious propaganda was openly sponsored and encouraged by the government, to which the Church was not given an opportunity to publicly respond. Seminaries were closed down, and the church was restricted from publishing materials. Atheism was propagated through schools, communist organizations, and the media. Organizations such as the Society of the Godless were created.

Freedom of movement

Emigration and any travel abroad were not allowed without an explicit permission from the government. People who were not allowed to leave the country and campaigned for their right to leave in the 1970s were known as "refuseniks". According to the Soviet Criminal Code, a refusal to return from abroad was treason, punishable by imprisonment for a term of 10–15 years, or death with confiscation of property.[14]

The passport system in the Soviet Union restricted migration of citizens within the country through the "propiska" (residential permit/registration system) and the use of internal passports. For a long period of Soviet history, peasants did not have internal passports, and could not move into towns without permission. Many former inmates received "wolf tickets" and were only allowed to live a minimum of 101 km away from city borders. Travel to closed cities and to the regions near USSR state borders was strongly restricted. An attempt to illegally escape abroad was punishable by imprisonment for 1–3 years.[14]

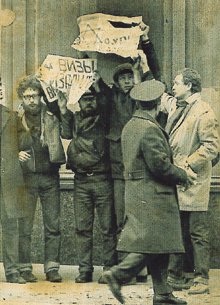

Human rights movement

Human rights activists in the Soviet Union were regularly subjected to harassment, repressions and arrests. In several cases, only the public profile of individual human rights campaigners such as Andrei Sakharov helped prevent a complete shutdown of the movement's activities.

The USSR and other countries of the Soviet bloc had abstained from voting on the 1948 U.N. Universal Declaration of Human Rights, citing its "overly juridical" character as well as the infringements on national sovereignty that it might enable.[27]: 167–169 Although the USSR and some of its allies did sign the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, these documents were neither well-known to people living under Communist rule nor taken seriously by the Communist authorities. Western governments did not emphasize human rights ideas in the early détente period.[28]: 117

Nevertheless, a more organized human rights movement grew out of the current of dissent known as "defenders of rights" (pravozashchitniki) of the late 1960s and 1970s.[29] One of its most important samizdat publications, the Chronicle of Current Events,[30] began circulation in 1968, after the United Nations declared the year as the International Year for Human Rights.

The following years saw the emergence of several dedicated human rights groups: The Initiative (or Action) Group for the Defense of Human Rights in the USSR (1969); the Committee on Human Rights in the USSR (1970); and the USSR's section of Amnesty International in 1973.[31] They wrote appeals, collected signatures for petitions, and attended trials.

The eight member countries of the Warsaw Pact signed the Helsinki Final Act in August 1975. The "third basket" of the Final Act included extensive human rights clauses.[32]: 99–100 In the years 1976–77, several "Helsinki Watch Groups" were formed in different cities to monitor the Soviet Union's compliance with the Helsinki Final Act, based in Moscow, Kiev, Vilnius, Tbilisi, and Erevan.[33]: 159–194 They succeeded in unifying different branches of the human rights movement.[32]: 159–166 Similar initiatives began in Soviet satellite states, such as Charter 77 in the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic.

Alternative views

Some Western academics argue that anticommunist narratives have exaggerated the extent of political repression and censorship in states under communist rule. Albert Szymanski, for instance, draws a comparison between the treatment of anticommunist dissidents in the Soviet Union after Stalin's death and the treatment of dissidents in the United States during the period of McCarthyism, claiming that "on the whole, it appears that the level of repression in the Soviet Union in the 1955 to 1980 period was at approximately the same level as in the U.S. during the McCarthy years (1947–56)."[34] Other scholars, such as Mark Aarons, contend that right-wing authoritarian regimes and dictatorships backed by Western powers committed atrocities and mass killings that rival the Communist world, citing examples such as the Indonesian occupation of East Timor, the Indonesian killings of 1965–66, the "disappearances" in Guatemala during the civil war, and the torture and killings associated with Operation Condor throughout South America.[35] Daniel Goldhagen claims that during the last two decades of the Cold War, the number of American client states practicing mass killing outnumbered those of the Soviet Union.[36] John Henry Coatsworth suggests the number of repression victims in Latin America alone far surpassed that of the Soviets and the Eastern bloc during the period 1960 to 1990.[37][38] In terms of living standards, economist Michael Ellman asserts that, in international comparisons, state-socialist nations compared favorably with capitalist nations in health indicators such as infant mortality and life expectancy.[39] Amartya Sen's own analysis of international comparisons of life expectancy found that several communist countries made significant gains, and commented "one thought that is bound to occur is that communism is good for poverty removal."[40] Poverty exploded following the collapse of the USSR in 1991, tripling to more than one-third of Russia's population in just three years.[41]

See also

- Human rights movement in the Soviet Union

- Article 6 of the Soviet Constitution (1977)

- Criticisms of Communist party rule

- Droughts and famines in Russia and the Soviet Union

- Human rights in Russia

- Mass killings in the Soviet Union

- Racism in the Soviet Union

- Soviet democracy

- Stalin and antisemitism

- Stalinism

- Totalitarianism

References

- ^ Houghton Miffin Company (2006)

- ^ Lambelet, Doriane. "The Contradiction Between Soviet and American Human Rights Doctrine: Reconciliation Through Perestroika and Pragmatism." 7 Boston University International Law Journal. 1989. pp. 61–62.

- ^ Shiman, David (1999). Economic and Social Justice: A Human Rights Perspective. Amnesty International. ISBN 0967533406.

- ^ a b c d e f Richard Pipes Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime, Vintage books, Random House Inc., New York, 1995, ISBN 0-394-50242-6, pages 402–403

- ^ Richard Pipes (2001) Communism Weidenfled and Nicoloson. ISBN 0-297-64688-5

- ^ Richard Pipes (1994) Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime. Vintage. ISBN 0-679-76184-5., pages 401–403.

- ^ Wyszyński, Andrzej (1949). Teoria dowodów sądowych w prawie radzieckim (PDF). Biblioteka Zrzeszenia Prawników Demokratów. pp. 153, 162, .

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Robert Conquest Reflections on a Ravaged Century (2000) ISBN 0-393-04818-7, page 97

- ^ Oleg Pshenichnyi (2015-08-22). "Засчитать поражение". Grani.ru. Retrieved August 23, 2015.

- ^ Yevgenia Albats and Catherine A. Fitzpatrick. The State Within a State: The KGB and Its Hold on Russia – Past, Present, and Future, 1994. ISBN 0-374-52738-5.

- ^ Anton Antonov-Ovseenko Beria (Russian) Moscow, AST, 1999. Russian text online

- ^ Koehler, John O. Stasi: The Untold Story of the East German Secret Police. Westview Press. 2000. ISBN 0-8133-3744-5

- ^ A Country Study: Soviet Union (Former). Chapter 9 – Mass Media and the Arts. The Library of Congress. Country Studies

- ^ a b c d e Biographical Dictionary of Dissidents in the Soviet Union, 1956–1975 By S. P. de Boer, E. J. Driessen, H. L. Verhaar; ISBN 90-247-2538-0; p. 652

- ^ Stalin, quoted in IS WAR INEVITABLE? being the full text of the interview given by JOSEPH STALIN to ROY HOWARD as recorded by K. UMANSKY, Friends of the Soviet Union, London, 1936

- ^ a b Feldbrugge, Simons (2002). Human Rights in Russia and Eastern Europe: essays in honor of Ger P. van den Berg. Kluwer Law International. ISBN 90-411-1951-5.

- ^ Davies and Wheatcroft, p. 401. For a review, see "Davies & Weatcroft, 2004" (PDF). Warwick.

- ^ "Ukrainian Famine". Ibiblio public library and digital archive. Retrieved 2011-04-21.

- ^ A Study of the Soviet economy, Volume 1. International Monetary Fund, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. 1991. ISBN 92-64-13468-9.

- ^ A Country Study: Soviet Union (Former). Chapter 5. Trade Unions. The Library of Congress. Country Studies. 2005.

- ^ Father Arseny 1893–1973 Priest, Prisoner, Spiritual Father. Introduction pg. vi–1. St Vladimir's Seminary Press ISBN 0-88141-180-9

- ^ a b L.Alexeeva, History of dissident movement in the USSR, in Russian

- ^ a b A.Ginzbourg, "Only one year", "Index" Magazine, in Russian

- ^ The Washington Post Anti-Communist Priest Gheorghe Calciu-Dumitreasa By Patricia Sullivan Washington Post Staff Writer Sunday, November 26, 2006; Page C09 http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/11/25/AR2006112500783.html

- ^ Dumitru Bacu (1971) The Anti-Humans. Student Re-Education in Romanian Prisons Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine, Soldiers of the Cross, Englewood, Colorado. Originally written in Romanian as Piteşti, Centru de Reeducare Studenţească, Madrid, 1963

- ^ Adrian Cioroianu, Pe umerii lui Marx. O introducere în istoria comunismului românesc ("On the Shoulders of Marx. An Incursion into the History of Romanian Communism"), Editura Curtea Veche, Bucharest, 2005

- ^ Mary Ann Glendon (2001). A World Made New: Eleanor Roosevelt and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. New York. ISBN 9780375760464.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Thomas, Daniel C. (2005). "Human Rights Ideas, the Demise of Communism, and the End of the Cold War". Journal of Cold War Studies. 7 (2): 110–141. doi:10.1162/1520397053630600.

- ^ Horvath, Robert (2005). "The rights-defenders". The Legacy of Soviet Dissent: Dissidents, Democratisation and Radical Nationalism in Russia. London; New York: RoutledgeCurzon. pp. 70–129. ISBN 9780203412855.

- ^ A Chronicle of Current Events (in English)

- ^ A Chronicle of Current Events No 17, 31 December 1970 — 17.4 "The Committee for Human Rights in the USSR".

- ^ a b Thomas, Daniel C. (2001). The Helsinki Effect: International Norms, Human Rights, and the Demise of Communism. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691048598.

- ^ Thomas, Daniel C. (2001). The Helsinki effect: international norms, human rights, and the demise of communism. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691048584.

- ^ Albert Szymanski, Human Rights in the Soviet Union, 1984, p. 291

- ^ Mark Aarons (2007). "Justice Betrayed: Post-1945 Responses to Genocide." In David A. Blumenthal and Timothy L. H. McCormack (eds). The Legacy of Nuremberg: Civilising Influence or Institutionalised Vengeance? (International Humanitarian Law). Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 9004156917 pp. 71 & 80–81

- ^ Daniel Goldhagen (2009). Worse Than War. PublicAffairs. ISBN 1-58648-769-8 p. 537

- "During the 1970s and 1980s, the number of American client states practicing mass-murderous politics exceeded those of the Soviets."

- ^ "The Cold War in Central America, 1975–1991" John H. Coatsworth, Ch 10

- ^ Noam Chomsky and Edward Herman (2014). The Washington Connection and Third World Fascism: The Political Economy of Human Rights: Volume I. Haymarket Books. p. xviii. ISBN 1608464067

- ^ Michael Ellman (2014). Socialist Planning. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1107427320 p. 372.

- ^ Richard G. Wilkinson. Unhealthy Societies: The Afflictions of Inequality. Routledge, November 1996. ISBN 0415092353. p. 122

- ^ Scheidel, Walter (2017). The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century. Princeton University Press. p. 222. ISBN 978-0691165028.

Bibliography

- Denial of human rights to Jews in the Soviet Union: hearings, Ninety-second Congress, first session. May 17, 1971. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1971.

- Human rights–Ukraine and the Soviet Union: hearing and markup before the Committee on Foreign Affairs and its Subcommittee on Human Rights and International Organizations, House of Representatives, Ninety-seventh Congress, First Session, on H. Con. Res. 111, H. Res. 152, H. Res. 193, July 28, July 30, and September 17, 1981. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1982.

- "Human rights: the dissidents v. Moscow". Time. 109 (8): 28. 21 February 1977.

- Applebaum, Anne (2003) Gulag: A History. Broadway Books. ISBN 0-7679-0056-1

- Boim, Leon (1976). "Human rights in the USSR". Review of Socialist Law. 2 (1): 173–187. doi:10.1163/157303576X00157.

- Chalidze, Valeriĭ (1971). Important aspects of human rights in the Soviet Union; a report to the Human Rights Committee. New York: American Jewish Committee. OCLC 317422393.

- Chalidze, Valery (January 1973). "The right of a convicted citizen to leave his country". Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review. 8 (1): 1–13.

- Conquest, Robert (1991) The Great Terror: A Reassessment. Oxford University Press ISBN 0-19-507132-8.

- Conquest, Robert (1986) The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505180-7.

- Courtois, Stephane; Werth, Nicolas; Panne, Jean-Louis; Paczkowski, Andrzej; Bartosek, Karel; Margolin, Jean-Louis & Kramer, Mark (1999). The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-07608-7.

- Daniel, Thomas (2001). The Helsinki effect: international norms, human rights, and the demise of communism. Princeton, N. J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691048598.

- Dean, Richard (January–March 1980). "Contacts with the West: the dissidents' view of Western support for the human rights movement in the Soviet Union". Universal Human Rights. 2 (1): 47–65. doi:10.2307/761802. JSTOR 761802.

- Fryer, Eugene (Spring 1979). "Soviet human rights: law and politics in perspective". Law and Contemporary Problems. 43 (2): 296–307. doi:10.2307/1191202. JSTOR 1191202.

- Graubert, Judah (October 1972). "Human rights problems in the Soviet Union". Journal of Intergroup Relations. 2 (2): 24–31.

- Johns, Michael (Fall 1987). "Seventy years of evil: Soviet crimes from Lenin to Gorbachev". Policy Review: 10–23.

- Khlevniuk, Oleg & Kozlov, Vladimir (2004) The History of the Gulag : From Collectivization to the Great Terror (Annals of Communism Series) Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09284-9.

- Samatan, Marie (1980). "Droits de l'homme et répression en URSS: l'appareil et les victimes" [Human rights and repression in the USSR: mechanism and victims] (in French). Paris: Seuil. ISBN 2020057050.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Pipes, Richard (2001) Communism Weidenfled and Nicoloson. ISBN 0-297-64688-5

- Pipes, Richard (1994) Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime. Vintage. ISBN 0-679-76184-5.

- Rummel, R.J. (1996) Lethal Politics: Soviet Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1917. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 1-56000-887-3.

- Szymanski, Albert (1984). Human rights: the USA and the USSR compared. Lawrence Hill & Co. ISBN 0882081586.

- Yakovlev, Alexander (2004). A Century of Violence in Soviet Russia. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10322-0.

External links

- Crimes of Soviet Communists — wide collection of sources and links.

- Chekists in Cassocks: The Orthodox Church and the KGB – by Keith Armes.

- G.Yakunin, l.Regelson. Letters from Moscow. Religion and Human Rights in USSR. – Keston College Edition.

- Love story under the H-bomb shadow – by K.E. Filipchuk and Z.K. Silagadze.