L.A. Confidential (film)

| L.A. Confidential | |

|---|---|

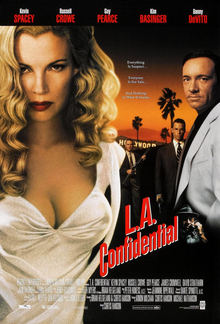

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Curtis Hanson |

| Written by | Curtis Hanson, Brian Helgeland based on a novel by James Ellroy |

| Produced by | Curtis Hanson Arnon Milchan Michael G. Nathanson |

| Starring | Kevin Spacey Russell Crowe Guy Pearce Kim Basinger James Cromwell Danny DeVito David Strathairn |

| Cinematography | Dante Spinotti |

| Edited by | Peter Honess |

| Music by | Jerry Goldsmith |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date | September 19, 1997 (U.S. release) |

Running time | 138 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $35,000,000 (estimated) |

| Box office | $126,216,940 |

L.A. Confidential is a 1997 American film based on the 1990 crime fiction novel of the same title by James Ellroy, the third in his L.A. Quartet novel cycle. Both the book and the film tell the story about a group of Los Angeles police in the 1950s, and police corruption bumping up against Hollywood celebrity. The film adaptation was produced and directed by Curtis Hanson and co-written by Hanson and Brian Helgeland.

At the time, Australian actors Guy Pearce and Russell Crowe were relatively unknown in North America, and one of the film's backers, Peter Dennett, was worried about the lack of established stars in the lead roles. However, he supported Hanson's casting decisions and this gave the director the confidence to approach Kevin Spacey, Kim Basinger, and Danny DeVito.

Critically acclaimed, the film holds a 99% rating at Rotten Tomatoes with 78 out of 79 reviews positive, as well as an aggregated rating of 90% based on 28 reviews on Metacritic. It was nominated for nine Academy Awards and won two, Basinger for Best Actress in a Supporting Role and Hanson and Helgeland for Best Screenplay - Adapted.

Plot synopsis

Set against the backdrop of the glamor, grit and noir of early 1950s Los Angeles, the film revolves around three Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) officers caught up in corruption, sex, lies, and murder following a multiple murder at the Nite Owl coffee shop. The story expands to encompass organized crime, political corruption, heroin, pornography, prostitution, tabloid journalism and institutional racism, which result in a huge body count. The novel's title refers to the infamous 1950s scandal magazine Confidential, portrayed fictionally as Hush-Hush (although a tabloid magazine called Hush-Hush also existed in the 1950s.[1])

Sergeant Edmund Exley (Pearce), the son of a legendary LAPD Inspector, is a brilliant officer in his own right, determined to outdo his father. Ed's intelligence, his education, his glasses, his insistence on following regulations, and his cold demeanor all contribute to his social isolation from other officers. He increases this resentment after volunteering to testify against other cops in an infamous police brutality case (the Bloody Christmas incident) early on, insisting on a promotion to Detective Lieutenant (which he receives) against the advice of Captain Dudley Smith (James Cromwell). The captain believed that Exley's honesty and actions as a "snitch" would interfere with his ability to supervise detectives. Exley was motivated by the murder of his father by "Rollo Tomasi", a sense of justice, and his personal ambition.

Officer Wendell "Bud" White (Crowe) is a violent 6-foot-tall brute and the most feared man in the LAPD. His plainclothes partner Dick Stensland was convicted and expelled from the force following a fictional version of the Bloody Christmas scandal as a scapegoat by the Chief of Police Thad Green and the District Attorney Ellis Loew; and by Exley's testimony. After these events, Bud vows revenge against Exley. His ties to the Nite Owl case become personal after Stensland is found to be one of the murder victims at the Nite Owl. He has a violent obsession with punishing woman-beaters, counterbalanced by his tenderness towards the victims. His temper often overpowers his thought, and he is perceived as a mindless thug. He is sought out by Capt. Dudley Smith for a black bag job intimidating out-of-town criminals trying to set up in Los Angeles after Mickey Cohen's conviction and incarceration.

Sergeant Jack Vincennes (Spacey) is a slick and likable Hollywood cop who works as the technical advisor of Badge of Honor, a popular Dragnet-type TV show. Vincennes is also connected with Sid Hudgens (DeVito) of Hush-Hush magazine. Vincennes receives kickbacks for making celebrity arrests, often orchestrated, involving narcotics, that will attract even more readers to the magazine—and more fame and profit to him. When a young actor winds up dead during one of these schemes, a guilt-ridden Vincennes is determined to find who did it.

At different intervals, the three men investigate the Nite Owl and concurrent events which in turn begin to reveal deep indications of corruption all around them. Ed Exley pursues absolute justice in the Nite Owl slayings, all the while trying to live up to his family's prestigious name. Bud White pursues Nite Owl victim Susan Lefferts, which leads him to Lynn Bracken (Basinger), a Veronica Lake look-alike and call-girl with pivotal ties to the case he and Exley are independently investigating. Meanwhile, Jack Vincennes follows up on a pornography racket that leads to ties to both the Nite Owl and Bracken's handler Pierce Patchett, operator of "Fleur-de-Lis", a call-girl service that runs prostitutes altered by plastic surgery to look like movie stars. All three men's fates are intertwined. A dramatic showdown occurs with powerful and corrupt forces within the city's political leadership and the department.

Cast

- Kevin Spacey as Det. Sgt. Jack Vincennes

- Russell Crowe as Officer Wendell "Bud" White

- Guy Pearce as Det. Lt. Edmund Jennings "Ed" Exley

- Kim Basinger as Lynn Bracken

- James Cromwell as Capt. Dudley Liam Smith

- Danny DeVito as Sid Hudgens

- David Strathairn as Pierce Morehouse Patchett

- Ron Rifkin as District Attorney Ellis Loew

- Graham Beckel as Det. Richard Alex "Dick" Stensland

- Paul Guilfoyle as Meyer Harris "Mickey" Cohen

- Matt McCoy as Brett Chase

- Paolo Seganti as Johnny Stompanato

- Simon Baker as Matt Reynolds

- Darrell Sandeen as Leland "Buzz" Meeks

- Marisol Padilla Sánchez as Inez Soto

Production

Origins

Curtis Hanson had read half a dozen of James Ellroy's books before he read L.A. Confidential and was drawn to its characters, not the plot. He said, "What hooked me on them was that, as I met them, one after the other, I didn't like them - but as I continued reading, I started to care about them."[2] Ellroy's novel also made Hanson think about L.A. and provided him with an opportunity to "set a movie at a point in time when the whole dream of Los Angeles, from that apparently golden era of the '20s and '30s, was being bulldozed."[2] Screenwriter Brian Helgeland was originally signed to Warner Brothers to write a Viking film with director Uli Edel and then worked on an unproduced modern-day King Arthur story. Helgeland was a long-time fan of Ellroy's novels. When he heard that Warner Bros. had acquired the rights to Confidential in 1990, he lobbied to script the film.[2] However, at the time, the studio was only talking to well-known screenwriters. When he finally did get a meeting, it was canceled two days before it was to occur.[2]

Helgeland found that Hanson had been hired to direct and met with him while the filmmaker was making The River Wild. They found that they not only shared a love for Ellroy's fiction but also agreed on how to adapt Confidential into a film. According to Helgeland, they had "to remove every scene from the book that didn't have the three main cops in it, and then to work from those scenes out."[2] According to Hanson, he "wanted the audience to be challenged but at the same time I didn't want them to get lost".[3] They worked on the script together for two years, with Hanson turning down jobs and Helgeland writing seven drafts for free.[2] The two men also got Ellroy's approval of their approach. He had seen Hanson's films, The Bedroom Window and Bad Influence and found him to be "a competent and interesting storyteller", but was not convinced that his book would be made into a film until he talked to the director.[2] He later said, "They preserved the basic integrity of the book and its main theme...Brian and Curtis took a work of fiction that had eight plotlines, reduced those to three, and retained the dramatic force of three men working out their destiny."[2]

Warner Bros. executive Bill Gerber showed the script to Michael Nathanson, CEO of New Regency Productions, which had a deal with the studio. Nathanson loved it, but they had to get the approval from the owner of New Regency, Arnon Milchan. Hanson prepared a presentation that consisted of 15 vintage postcards and pictures of L.A. mounted on poster-boards and made his pitch to Milchan. The pictures consisted of orange groves, beaches, tract homes in the San Fernando Valley, and the opening of the Hollywood Freeway to symbolize the image of prosperity sold to the public.[2]

Then, Hanson showed the darker side of Ellroy's novel with the cover of scandal rag, Confidential and the famous shot of Robert Mitchum coming out of jail after his marijuana bust. He also had photographs of jazz musicians of the time: Zoot Sims, Gerry Mulligan, and Chet Baker to represent the music people listened to.[2] Hanson emphasized that the period detail would be in the background and the characters in the foreground. Milchan was impressed with his presentation and agreed to finance it.

Casting

Hanson had seen Russell Crowe in Romper Stomper and found him "repulsive and scary but captivating".[2] The actor had read Ellroy's The Black Dahlia but not L.A. Confidential. When he read the script, Crowe was drawn to Bud White's "self-righteous moral crusade".[4] Crowe fit the visual preconception of Bud. Hanson put the actor on tape doing a few scenes from the script and showed it to the film's producers, who agreed to cast him as Bud.[5] Guy Pearce auditioned like countless other actors and Hanson felt that he "was very much what I had in mind for Ed Exley".[2] The director purposely did not watch the actor in Priscilla, Queen of the Desert afraid that it might taint his decision.[5] As he did with Crowe, Hanson taped Pearce and showed it to the producers, who agreed he should be cast as Exley. Pearce did not like Exley when he first read the screenplay and remarked, "I was pretty quick to judge him and dislike him for being so self-righteous ... But I liked how honest he became about himself. I knew I could grow to respect and understand him".[6]

Milchan was against casting "two Australians" in the American period piece (as Pearce wryly commented in a later interview, he is English, while Crowe is a New Zealander). Besides their ethnic heritage, both Crowe and Pearce were relative unknowns in North America and Milchan was equally worried about the lack of movie stars in the lead roles.[2]

However, Milchan supported Hanson's casting decisions and this gave the director the confidence to approach Kim Basinger, Danny DeVito and Kevin Spacey. Hanson cast Crowe and Pearce because he wanted to "replicate my experience of the book. You don't like any of these characters at first, but the deeper you get into their story, the more you begin to sympathize with them. I didn't want actors audiences knew and already liked."[7]

Hanson felt that the character of Jack Vincennes was "a movie star among cops" and thought of Spacey with his "movie star charisma", casting him specifically against type.[5] The director was confident that the actor "could play the man behind that veneer, the man who also lost his soul", and when he gave him the script, he told him to think of Dean Martin while in the role.[5] Hanson cast Basinger because he felt that she "was the character to me. What beauty today could project the glamor of Hollywood's golden age?"[7]

Pre-production

To give his cast and crew points and counterpoints to capture L.A. in the 1950s, he held a "mini-film festival", showing one film a week: The Bad and the Beautiful because it epitomized the glamorous Hollywood look; In a Lonely Place, because it showed the ugly side of Hollywood glamor; Don Siegel's The Lineup and Private Hell 36, "for their lean and efficient style";[5] and Kiss Me Deadly, because it was "so rooted in the futuristic 50s: the atomic age".[2][5] Hanson and the film's cinematographer Dante Spinotti agreed that the film would be shot widescreen and watched two Cinemascope films from the period: Douglas Sirk's The Tarnished Angels and Vincente Minnelli's Some Came Running.

Before filming took place, Hanson brought Crowe and Pearce to L.A. for two months to immerse them in the city and the time period.[7] He also got them dialect coaches, showed them vintage police training films and had them meet real cops.[7] Pearce found the contemporary police force had changed too much to be useful research material and disliked the police officer he rode around with because he was racist.[8] The actor found the police films more valuable "because there was a real sort of stiffness, a woodenness about these people" that he felt Exley had as well.[7] Crowe studied Sterling Hayden in Stanley Kubrick's crime film, The Killing "for that beefy manliness that came out of World War II."[5] For six weeks, Crowe, Pearce, Hanson and Helgeland conducted rehearsals, which consisted of their discussing each scene in the script.[9] As other actors were cast they would join in.[5]

Principal photography

Hanson did not want the film to be an exercise in nostalgia and had Spinotti shoot it like a contemporary film and use more naturalistic lighting than in a classic film noir.[10] He told Spinotti and the film's production designer Jeannine Oppewall to pay great attention to period detail but to then "put it all in the background".[5]

Music

Jerry Goldsmith's score for the film was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Original Dramatic Score, but lost to James Horner's score for Best Picture Titanic.[11]

Reception

The film was screened at the 1997 Cannes Film Festival.[12] According to Hanson, Warner Brothers did not want it shown at Cannes, because they felt that there was an "anti-studio bias ... So why go and come home a loser?"[5] However, Hanson wanted to debut the film at a high profile, international venue like Cannes. He and other producers bypassed the studio and sent a print directly to the festival's selection committee, which loved it.[10] Ellroy saw the film and said, "I understood in 40 minutes or so that it is a work of art on its own level. It was amazing to see the physical incarnation of the characters".[2]

Box office

L.A. Confidential was released on September 19, 1997 in 769 theaters, grossing $5.2 million on its opening weekend. On October 3, it was given an expanded release in 1,625 theaters. It went on to make $64.6 million in North America and $61.6 million in the rest of the world, for a worldwide total of $126.2 million.[13]

Critical response

Overall, L.A. Confidential scored very well with critics, presently sporting a rare 99% "Certified Fresh" approval rating at Rotten Tomatoes with 78 out of 79 reviews positive. Film critic Roger Ebert gave the film four out of four stars and described it as "seductive and beautiful, cynical and twisted, and one of the best films of the year".[14] Later, he included it as one of his "Great Movies" and described it as "film noir, and so it is, but it is more: Unusually for a crime film, it deals with the psychology of the characters ... It contains all the elements of police action, but in a sharply clipped, more economical style; the action exists not for itself but to provide an arena for the personalities".[15] In her review for the New York Times, Janet Maslin wrote, "Mr. Spacey is at his insinuating best, languid and debonair, in a much more offbeat performance than this film could have drawn from a more conventional star. And the two Australian actors, tightly wound Mr. Pearce and fiery, brawny Mr. Crowe, qualify as revelations".[16] Desson Howe, in his review for the Washington Post, praised the cast: "Pearce makes a wonderful prude who gets progressively tougher and more jaded. New Zealand-born Crowe has a unique and sexy toughness; imagine Mickey Rourke without the attitude. Although she's playing a stock character, Basinger exudes a sort of chaste sultriness. Spacey is always enjoyable".[17]

In his review for the Globe and Mail, Liam Lacey wrote, "The big star is Los Angeles itself. Like Roman Polanski's depiction of Los Angeles in the thirties in Chinatown, the atmosphere and detailed production design are a rich gel where the strands of narrative form".[18] USA Today gave the film three-and-a-half stars out of four, praising the screenplay: "it appears as if screenwriters Brian Helgeland and Curtis Hanson have pulled off a miracle in keeping multiple stories straight. Have they ever. Ellroy's novel has four extra layers of plot and three times as many characters ... the writers have trimmed unwieldy muscle, not just fat, and gotten away with it".[19] In his review for Newsweek, David Ansen wrote, L.A. Confidential asks the audience to raise its level a bit, too - you actually have to pay attention to follow the double-crossing intricacies of the plot. The reward for your work is dark and dirty fun".[20] Richard Schickel, in his review for Time, wrote, "It's a movie of shadows and half lights, the best approximation of the old black-and-white noir look anyone has yet managed on color stock. But it's no idle exercise in style. The film's look suggests how deep the tradition of police corruption runs".[21]

In his review for the New York Observer, Andrew Sarris wrote, "Mr. Crowe strikes the deepest registers with the tortured character of Bud White, a part that has had less cut out of it from the book than either Mr. Spacey's or Mr. Pearce's ... but Mr. Crowe at moments reminded me of James Cagney's poignant performance in Charles Vidor's Love Me or Leave Me (1955), and I can think of no higher praise".[22] Kenneth Turan, in his review for Los Angeles Times, wrote, "The only potential audience drawback L.A. Confidential has is its reliance on unsettling bursts of violence, both bloody shootings and intense physical beatings that give the picture a palpable air of menace. Overriding that, finally, is the film's complete command of its material".[23] In his review for The Independent, Ryan Gilbey wrote, "In fact, it's a very well made and intelligent picture, assembled with an attention to detail, both in plot and characterisation, that you might have feared was all but extinct in mainstream American cinema".[24] Richard Williams, in his review for The Guardian, wrote, "L.A. Confidential gets just about everything right. The light, the architecture, the slang, the music ... A wonderful Lana Turner joke. A sense, above all, of damaged people arriving to make new lives and getting seduced by the scent of night-blooming jasmine, the perfume of corruption".[25]

Awards

L.A. Confidential was nominated for nine Academy Awards and won two, Kim Basinger for Best Actress in a Supporting Role and Curtis Hanson and Brian Helgeland for Best Screenplay - Adapted. It was also nominated for Best Picture, Director, Art Direction, Cinematography, Film Editing, Original Score and Sound.[26] Kim Basinger tied for the Best Supporting Actress with Gloria Stuart from Titanic at the 4th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards.[27]

Time ranked L.A. Confidential the best film of 1997.[28] The National Society of Film Critics also ranked it the best film of the year and Curtis Hanson was voted Best Director.[29] The New York Film Critics Circle also voted L.A. Confidential as best film of 1997 in addition to ranking Hanson as best director and he and Brian Helgeland with the best screenplay.[30] The Los Angeles Film Critics Association and the National Board of Review also voted L.A. Confidential as the best film of 1997. As a result, L.A. Confidential is the second film in history (along with Schindler's List) to obtain the distinction of sweeping the "Big Four" critics awards.[29]

It was also voted as the best film set in Los Angeles in the last 25 years by a group of Los Angeles Times writers and editors with two criteria: "The movie had to communicate some inherent truth about the L.A. experience, and only one film per director was allowed on the list".[31] In 2009, the London Film Critics' Circle voted L.A. Confidential one of the best movies of the last 30 years.[32]

Home media

A Two-Disc Special Edition was released on DVD and Blu-ray on September 23, 2008.[33]

References

- ^ [1]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Sragow, Michael (September 11, 1997). "City of Angles". Dallas Observer.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Dawson, Jeff (December 1997). "Mean Streets". Empire.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Smith, Adam (December 1997). "The Nearly Man...". Empire.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Taubin, Amy (November 1997). "L.A. Lurid". Sight and Sound.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Kempley, Rita (September 21, 1997). "Guy Pearce Cuts Through the Chase". Washington Post.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c d e Veniere, James (September 14, 1997). "Director of L.A. Confidential Hits Stride". Boston Herald.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Hemblade, Christopher (December 1997). "Breaking the Mould...". Empire.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Arnold, Gary (September 21, 1997). "Casting for L.A. Confidential went in unexpected direction". Washington Times. pp. D3.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Taubin, Amy (September 23, 1997). "Confidentially Speaking: Curtis Hanson Makes a Studio-Indie Hybrid". Village Voice.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ http://www.oscars.org/awards/academyawards/oscarlegacy/1990-1999/70nominees.html

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: L.A. Confidential". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2009-09-22.

- ^ "L.A. Confidential". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2009-01-07.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Ebert, Roger (September 19, 1997). "L.A. Confidential". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2009-01-07.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Ebert, Roger (September 4, 2008). "Great Movies: L.A. Confidential". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2009-01-07.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Maslin, Janet (September 19, 1997). "The Dark Underbelly of a Sunny Town". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-01-07.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Howe, Desson (September 19, 1997). "Noir Confidential: A Clever Case". Washington Post.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Lacey, Liam (September 19, 1997). "L.A. Confidential". Globe and Mail. pp. C1.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Clark, Mike (September 19, 1997). "Cool L.A. Confidential: Classic film noir to the core". USA Today. pp. 1D.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Ansen, David (September 22, 1997). "Noir Kind of Town". Newsweek. p. 83.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Schickel, Richard (September 15, 1997). "Three L.A. Cops, One Philip Marlowe". Time. Retrieved 2009-01-07.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Sarris, Andrew (September 28, 1997). "Confidentially Speaking, Noir's Gone Hollywood". New York Observer. Retrieved 2009-01-07.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Turan, Kenneth (September 19, 1997). "L.A. Confidential". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2009-01-07.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Gilbey, Ryan (October 31, 1997). "Thugs, pigs and paparazzi in Fifties LA". The Independent. p. 8.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Williams, Richard (October 31, 1997). "LAPD blue". The Guardian. p. 6.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Weinraub, Bernard (March 24, 1998). "Titanic Ties Record With 11 Oscars, Including Best Picture". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-01-07.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Van Gelder, Lawrence (March 10, 1998). "Footlights". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-01-07.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "The Best Cinema of 1997". Time. December 29, 1997. Retrieved 2009-01-07.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Lyman, Rick (January 5, 1998). "L.A. Confidential Wins National Critics' Awards". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-01-07.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Maslin, Janet (December 12, 1998). "L.A. Confidential Wins Critics Circle Award". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-01-07.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Boucher, Geoff (August 31, 2008). "The 25 best L.A. films of the last 25 years". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2008-08-31.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Child, Ben (December 1, 2009). "Apocalypse Now tops London critics' 30th anniversary poll". The Guardian. Retrieved 2009-12-02.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "L.A. Confidential Two-Disc Special Edition". Business Wire. June 16, 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-17.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

Further reading

- Dargis, Manohla (2003). L.A. Confidential (BFI Modern Classics). British Film Institute. ISBN 0-85170-944-3.

External links

- 1997 films

- American crime films

- 1990s crime films

- Edgar Award winning works

- Films based on mystery novels

- Films directed by Curtis Hanson

- Films featuring a Best Supporting Actress Academy Award winning performance

- Films featuring a Best Supporting Actress Golden Globe winning performance

- Films set in Los Angeles, California

- Films set in the 1950s

- Films whose writer won the Best Adapted Screenplay Academy Award

- American mystery films

- Neo-noir

- Police detective films

- Warner Bros. films

- Regency films