New Hebrides

This article relies largely or entirely on a single source. (June 2013) |

New Hebrides Condominium Condominium des Nouvelles-Hébrides | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1906–1980 | |||||||||

New Hebrides | |||||||||

| Capital | Port Vila | ||||||||

| Common languages | English, French, Bislama | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 1906 | ||||||||

| 30 July 1980 | |||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 1976 | 12,189 km2 (4,706 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1976 | 100,000 | ||||||||

| Currency | New Hebrides franc | ||||||||

| |||||||||

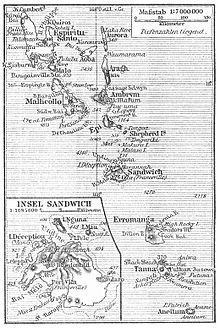

New Hebrides was the colonial name for an island group in the South Pacific that now forms the nation of Vanuatu. Native people had inhabited the islands for thousands of years before the first Europeans arrived in 1606 from a Spanish expedition led by Pedro Fernandes de Queirós. The islands were colonized by both the British and French in the 18th century shortly after Captain James Cook visited the islands. The two countries eventually signed an agreement making the islands an Anglo-French condominium, which lasted from 1906 until 1980, when the New Hebrides gained their independence as Vanuatu.

The Condominium divided the New Hebrides into two separate communities—one Anglophone and one Francophone. This divide continues even after independence, with schools either teaching in one language or the other, and between different political parties.

Politics and economy

The New Hebrides was a rare form of colonial territory in which sovereignty was shared by two powers, Britain and France, instead of just one. Under the Condominium there were three separate governments – one French, one British, and one joint administration that was partially elected after 1975.

The French and British governments were called residencies, each headed by a resident appointed by the metropolitan government. The residency structure greatly emphasized dualism, with both consisting of an equal number of French and British representatives, bureaucrats and administrators. Every member of one residency always had an exact mirror opposite number on the other side who they could consult. The symmetry between the two residencies was almost exact.

The joint government consisted of both local and European officials. It had jurisdiction over the postal service, public radio station, public works, infrastructure, and censuses, among other things. The two main cities of Santo and Port Vila also had city councils, but these did not have a great deal of authority[clarification needed].

Local people could choose whether to be tried under the British common law or the French civil law. Visitors could choose which immigration rules to enter under. Nationals of one country could set up corporations under the laws of the other. In addition to these two legal systems, a third Native Court existed to handle cases involving Melanesian customary law. The presiding judge of the Native Court was appointed by the King of Spain however, not by the British or the French.

There were two prison systems to complement the two court systems. The police force was technically unified but consisted of two chiefs and two equal groups of officers wearing two different uniforms. Each group alternated duties and assignments.

Language was a serious barrier to the operation of this naturally inefficient system, as all documents had to be translated once to be understood by one side, then the response translated again to be understood by the other, though Bislama creole represented an informal bridge between the British and the French camps.

See also

- Coconut War

- French colonial empire

- List of French possessions and colonies

- List of colonial heads of Vanuatu (New Hebrides)

- Postage stamps and postal history of the New Hebrides

- History of Vanuatu

References

Peck, John G. (2005). "A Brief Overview of the Old New Hebrides" (PDF). Palmerston North, New Zealand: School of Psychology, Massey University. Retrieved 2008-02-05. {{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires |journal= (help); Unknown parameter |coauthors= ignored (|author= suggested) (help)